In response to Kennedy's May 25th address to congress and the nation, Korolev and Khrushchev immediately began an informal dialog over the situation as they both took it quite seriously. Authorization for draft work for a booster and spacecraft capable of taking cosmonauts to the Lunar Surface was given on June 1st.

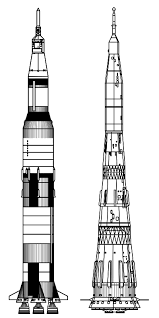

Despite intense criticism by Glushko and Keldysh the rest of the expert commission supported the draft project. The chosen vehicle was Korolev's N1, while significantly more complex than Chelomei’s UR-700, it was, nonetheless, deemed the more realistic proposal. Although it's payload capacity of just 75,000 kg made it a tight squeeze for any potential lunar landing architecture as it was originally envisioned for Lunar Orbital missions only.

The mission profile chosen by the Soviet Union differed from the three American options then under discussion (EOR, LOR and Direct Ascent). While originally favoured before the sense of urgency it became clear that an EOR architecture with a direct return lander wasn't practical as it would require three N1 launches plus one Soyuz 11A51, rendezvous and docking in LEO. Single-Launch Lunar Orbit Rendezvous was not a practical option either as using this method would stretch beyond the mass budget of a single N1. This meant that the final architecture would utilize a dual launch/LOR profile, involving two separate launches of the Lunar Orbiter and the Lunar Excursion vehicle being sent directly into Lunar Orbit and docking (from that point on the mission was identical to the LOR profile). It also allowed for a single launch architecture with later upgrades and higher mass margins for the lander and Orbiter. The Americans chose the large Saturn C-5 as the basis for a singe, rather than dual launch LOR architecture. Despite this the "Lunar Excursion Module" still required two dockings (although only a single rendezvous) as compared to the Soviet's Architecture. Both risked an unsuccessful rendezvous after the ascent (potentially fatal in both cases) however the mass savings warranted it.

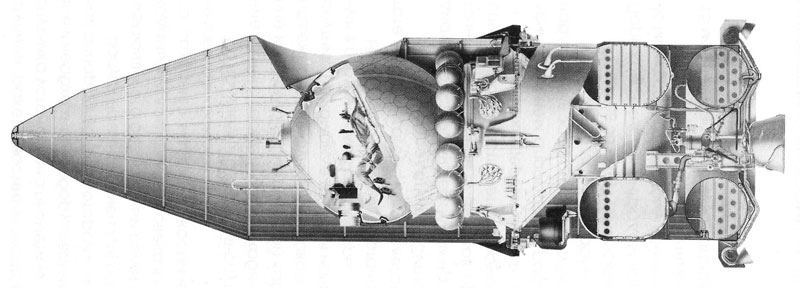

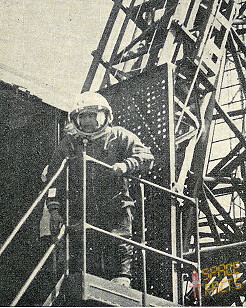

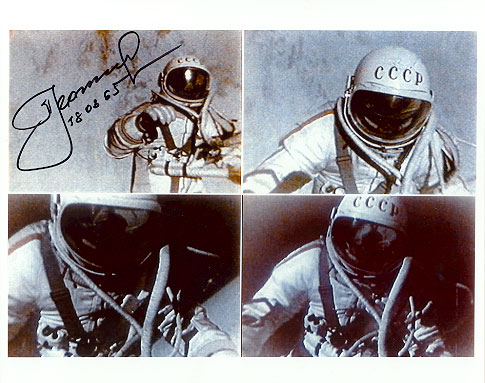

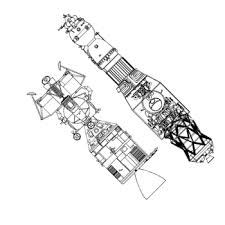

The actual spacecraft themselves were both fairly similar in function and purpose but radically different in approach. The Apollo Command/Service Module (CSM) was significantly heavier with a total weight/mass of well over 18 tonnes even for the stripped down Block-1 LEO version (hence reliant on the undeveloped Saturn C-1). The Block-2 variant actually capable of conducting lunar missions weighed in at 30 tonnes! A by-product of this was the complete reliance on the Saturn C-5 even for circumlunar missions. The Soviet approach utilized a disposable habitation module to reduce the mass of the Soyuz down to just 6 tonnes while allowing it to have significantly more internal volume than the Apollo CSM. This provided an important benefit as it meant the Soyuz could be tested on an existing (and reliable) R-7. In 1962 the un-named spacecraft was dubbed "Soyuz". Both were capable of taking a crew of three and supporting them for over two weeks in LEO, cis-lunar space, or in Low Lunar Orbit. An important difference between the Apollo and Soyuz vehicles was that the Soyuz required the cosmonauts to spacewalk in order to enter and leave the lunar landing vehicle, unlike Apollo which had a pressurized tunnel between the two vehicle.

The lunar Landers also varied significantly as the LK lander had a fully fuelled mass of just 7,000 kg. By comparison the American "Lunar Excursion Module" had a mass of 14,696 kg, over twice that of the LK. This was important as it meant the Soviets could test the LK in LEO using existing R-7s unlike the Americans who (once again) had to wait for the undeveloped Saturn C-1. It was significantly smaller but was still capable (if only just) of bringing a crew of two on short, sortie missions. Multi-day mission extensions were also a possibility given it's mass margins.

Following the approval of the draft project there was a more informal discussion between Khrushchev and the Chief Designers at the Soviet leader's estate at Pitsunda, on the Black Sea, in August. The official decree authorising N-I production was issued in the beginning of 1962 with first flight to occur in 1965. This brought the beginning of actual development work at nearly the same time as Apollo.

BTW: This is a collaborative TL between SpaceGeek and Bahamut-255

Despite intense criticism by Glushko and Keldysh the rest of the expert commission supported the draft project. The chosen vehicle was Korolev's N1, while significantly more complex than Chelomei’s UR-700, it was, nonetheless, deemed the more realistic proposal. Although it's payload capacity of just 75,000 kg made it a tight squeeze for any potential lunar landing architecture as it was originally envisioned for Lunar Orbital missions only.

The mission profile chosen by the Soviet Union differed from the three American options then under discussion (EOR, LOR and Direct Ascent). While originally favoured before the sense of urgency it became clear that an EOR architecture with a direct return lander wasn't practical as it would require three N1 launches plus one Soyuz 11A51, rendezvous and docking in LEO. Single-Launch Lunar Orbit Rendezvous was not a practical option either as using this method would stretch beyond the mass budget of a single N1. This meant that the final architecture would utilize a dual launch/LOR profile, involving two separate launches of the Lunar Orbiter and the Lunar Excursion vehicle being sent directly into Lunar Orbit and docking (from that point on the mission was identical to the LOR profile). It also allowed for a single launch architecture with later upgrades and higher mass margins for the lander and Orbiter. The Americans chose the large Saturn C-5 as the basis for a singe, rather than dual launch LOR architecture. Despite this the "Lunar Excursion Module" still required two dockings (although only a single rendezvous) as compared to the Soviet's Architecture. Both risked an unsuccessful rendezvous after the ascent (potentially fatal in both cases) however the mass savings warranted it.

The actual spacecraft themselves were both fairly similar in function and purpose but radically different in approach. The Apollo Command/Service Module (CSM) was significantly heavier with a total weight/mass of well over 18 tonnes even for the stripped down Block-1 LEO version (hence reliant on the undeveloped Saturn C-1). The Block-2 variant actually capable of conducting lunar missions weighed in at 30 tonnes! A by-product of this was the complete reliance on the Saturn C-5 even for circumlunar missions. The Soviet approach utilized a disposable habitation module to reduce the mass of the Soyuz down to just 6 tonnes while allowing it to have significantly more internal volume than the Apollo CSM. This provided an important benefit as it meant the Soyuz could be tested on an existing (and reliable) R-7. In 1962 the un-named spacecraft was dubbed "Soyuz". Both were capable of taking a crew of three and supporting them for over two weeks in LEO, cis-lunar space, or in Low Lunar Orbit. An important difference between the Apollo and Soyuz vehicles was that the Soyuz required the cosmonauts to spacewalk in order to enter and leave the lunar landing vehicle, unlike Apollo which had a pressurized tunnel between the two vehicle.

The lunar Landers also varied significantly as the LK lander had a fully fuelled mass of just 7,000 kg. By comparison the American "Lunar Excursion Module" had a mass of 14,696 kg, over twice that of the LK. This was important as it meant the Soviets could test the LK in LEO using existing R-7s unlike the Americans who (once again) had to wait for the undeveloped Saturn C-1. It was significantly smaller but was still capable (if only just) of bringing a crew of two on short, sortie missions. Multi-day mission extensions were also a possibility given it's mass margins.

Following the approval of the draft project there was a more informal discussion between Khrushchev and the Chief Designers at the Soviet leader's estate at Pitsunda, on the Black Sea, in August. The official decree authorising N-I production was issued in the beginning of 1962 with first flight to occur in 1965. This brought the beginning of actual development work at nearly the same time as Apollo.

BTW: This is a collaborative TL between SpaceGeek and Bahamut-255

Last edited: