You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Rally for the Farmers! Willie Nelson and the late 20th century populist movement

- Thread starter Baconheimer

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 25 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

1998 Downballot Results (Part 2) Where are they now? Things Fall Apart: 1999 2000 Major Party Nominations Mere Anarchy: 2000 Minor Party Nominations Religion and Politics in the 1990s Preview of 2000 Senate Elections The Second Coming: Election Day 2000I'll say one thing: it's a strong field and whoever your candidate is, they'll have a tough time taking the nomination against all these heavy hitters.Come on Casey you can do it.

Maybe that no one gets the nomination until the last moment and we get a good old fashioned fist fight convention. That be fun...and terrible for the party but still quite fun.I'll say one thing: it's a strong field and whoever your candidate is, they'll have a tough time taking the nomination against all these heavy hitters.

It could be damaging. On the other hand though, it might be a risk Rallyites are willing to take considering the state of the opposition.Maybe that no one gets the nomination until the last moment and we get a good old fashioned fist fight convention. That be fun...and terrible for the party but still quite fun.

Bookmark1995

Banned

It could be damaging. On the other hand though, it might be a risk Rallyites are willing to take considering the state of the opposition.

Either way, this next election is going to be quite a fracas.

That's something I can promise without giving away any information.Either way, this next election is going to be quite a fracas.

The next update should be monstrous at over 4,000 words. It will cover all three “major” party nominations though and should be done in the next day or so.

That's something I can promise without giving away any information.

A contingent election, I'm guessing? I don't see how that could yield anything other than Republican victory, though.

2000 Major Party Nominations

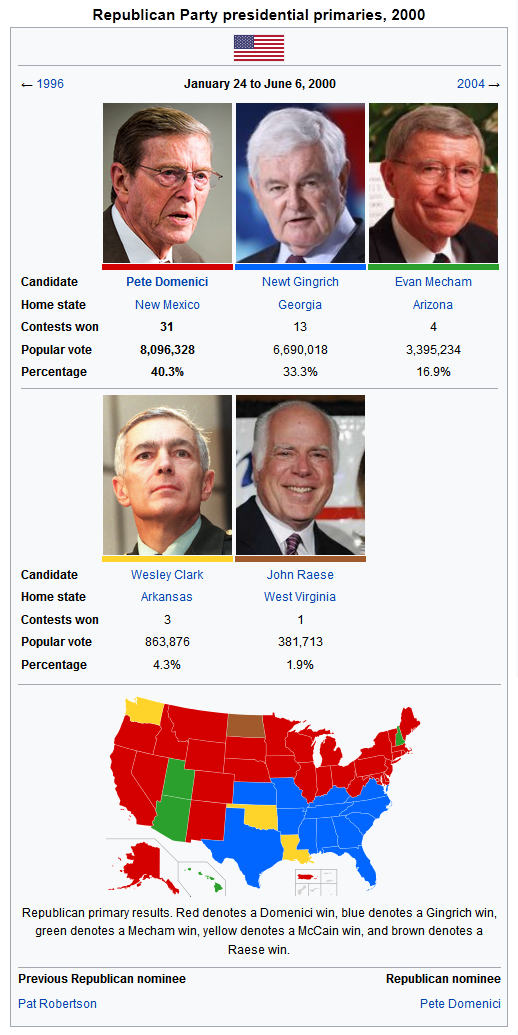

The 2000 Republican nomination was, at its core, a referendum on Pat Robertson. The fiery Robertson was able to transform doubts about the Hart administration and anger at the establishment for the sale of American guns to Iran and subsequent attempted cover-up by that aristocrat George Bush into a winning coalition in the Republican primary and then the general election. The division of the opposition into three separate tickets, each with distinct appeal further sealed the deal. But perhaps as important as all this in winning the election of 1992 was Lee Atwater and the Machiavellian operatives that worked under him. Though Robertson’s early administration was successful owing to Atwater and his guile as well as Republican majorities in both houses, the tight leash held on the President by party officials slowly slackened.

It took several years for real problems to arise. Less oversight meant Robertson had an increasing number of embarrassing gaffes,some highly offensive and alienating and authorized some politically poor decisions like the Invasion of Libya, and the natural conclusion of some of the President’s better initiatives, like Branstad v. Planned Parenthood put liberals on the back foot and ready to fight. Unfortunately, all this coincided with the Rally for the Farmers fully supplanting the Democrats and therefore providing an effective opposition to Robertson and Congressional Republicans.

Seeing this, much of the Republican Party shifted away from Robertson and though they resisted the calls for impeachment, they effectively made him a lame-duck President from 1999 onwards. Of course, there were those that still firmly backed Pat Robertson: Senators Evan Mecham of Arizona as well as Helms and East of North Carolina and the ultraconservative Jack Fellure of West Virginia’s Third district.

Two unabashedly Robertsonite major candidates filed (though only one would gain any traction): the aforementioned Senator Mecham and Former Secretary of Housing and Urban Development Morry Taylor, who had served from 1993 to 1997. Mecham had significant baggage: he had referred to African American children as “pickaninnies” and had claimed that America was a Christian nation and therefore Muslims and Jews (though he later strongly retracted the second part of this statement) were ineligible for public office. Mecham appropriated the name of a song penned to satirize him in the 1980s while he was Governor of Arizona, “You Can Call Me Ev” as a campaign slogan intended to evoke a folksy image. Taylor, nicknamed “The Grizz”, is a selfmade millionaire who took a single factory into an international tire business. While Taylor has never held elected office, he avoided many of the blunders that plagued Mecham. Taylor ran a much more economically-focused campaign, portraying himself as a successful businessman that would cut down on waste in the federal government. While Taylor his backers, he was unable to gain serious support, even in his home state of Iowa.

The two main contenders, however, were Vice President Gingrich and Former Secretary of State Pete Domenici. Gingrich, House Republican Whip before he was tapped to fill the assassinated Vice President Heinz’s shoes, was the attack dog of the Republican Party. Speaker Cheney was the respectable, public face of the House Republicans while Gingrich viciously blasted liberals inside and outside of the party. Gingrich toed a strong socially and fiscally conservative line and was the President’s number one man in the House, but that began to change after Gingrich became Vice President. Gingrich may have been an ideologue, but he could tell when a ship was sinking, so he began distancing himself from the Robertson administration in 1997. Gingrich’s appointment had effectively started a war between the Georgian and Domenici. As early as election night 1996, it was clear in Republican circles that Domenici wanted (and would likely get) the nod in 2000. Gingrich’s appointment and leaked statements from the Oval Office infuriated Domenici, who came to believe that Gingrich was Robertson’s favorite. Domenici himself became something of a critic of Pat Robertson during that administration’s last days in office. Though Pete Domenici was a conservative in most matters, he was uncomfortable with the extreme rhetoric from the White House, which was something that prompted him to resign from the State Department in February 1997. Domenici and Gingrich traded shots as early as 1998, two years before the Presidential election.

But of course, there were more. Former Representative Jack Kemp (who had come second in the 1992 primaries) entered the fray. Kemp had transformed during the Robertson years. He had served in Congress until 1994, but declined to run again that year. Since then, Kemp had shifted leftward on some social issues and had become what might be called a libertarian. There was also West Virginia Governor John Raese. Raese touted success in keeping the struggling West Virginia coal industry alive and compromise with the significant Democratic and then Rallyite state legislative delegations. While personally supportive of Robertson, Raese knew that his path to victory would require a less enthusiastic tone towards the President, and attempted to lie low on that subject. But one could not forget Wesley Clark. Clark, at 55 had never held elected office, but was a General in the US Army and a decorated combat veteran. Clark had served in Vietnam, where he was awarded the Silver Star, and then during the Invasion of Iraq. But Clark’s fame came from the Invasion of Libya, in which he was the Supreme Commander of Allied forces. In a masterful campaign, Libya fell within three weeks with few casualties during the initial invasion (though many would die in the subsequent occupation) Despite this, Clark was recalled to Washington on the orders of Pat Robertson himself, and Clark had been mustered out by the end of 1998. His Presidential campaign started barely six months later, in June of 1999. Clark portrayed himself as the national security candidate, and touted his ability to hold together the frayed Anglo-American Alliance in the recent Middle Eastern conflicts.

The campaigning season brought some surprises. Though on paper Wesley Clark was a solid candidate, he proved gaffe-prone. Advocating for internment camps on American soil turned many off to a Clark candidacy and suggesting the military have more of a role in American decision-making. Everyone knew Evan Mecham was a wildcard and prone to bizarre stunts, but his meeting with Canadian Regional Congress electoral alliance leader John Turmel was totally expected. Immediately, Democrats, the Rally, the American foreign service community, establishment Republicans, and even conservatives that realized talking to the leaders of secessionist groups in neighboring countries is not a good idea howled protest (a Senate censure failed to take the wind out of the Mecham campaign’s sails and, indeed might have helped him in some quarters)

Domenici came out on top in the Alaska Caucuses, but with no delegates assigned, it was a only a moral victory for the former Secretary of State’s camp. Domenici took Iowa that same day in a convincing victory. A week later, backed by Gordon Humphrey, Bob Smith, and Meldrim Thomson, Mecham scored a modest victory in the New Hampshire primary. Taylor and Kemp, whose campaigns hinged on upsets in Iowa and New Hampshire respectively, dropped out without endorsing any other candidate. The optimism among conservatives following Mecham’s New Hampshire victory proved misplaced as Domenici took Delaware and Gingrich South Carolina the next week. Mecham’s campaign simply had not put enough resources into the south, where favorite son Newt Gingrich was still popular. The New Hampshire upset could be ascribed to a favorable environment and lack of any candidates hailing from the region (aside from Jack Kemp, of course) Raese even picked up North Dakota before dropping out from a lack of funds (and just in time to return to West Virginia and file to run for a second term as Governor) Wesley Clark saw an upset in Washington, but all this was too little and too late as the showdown between Pete Domenici and Newt Gingrich, something both candidates had prepared for since 1998, began.

In a sense, the Domenici-Gingrich fight was one for the very heart of the GOP. Domenici, despite his service as Secretary of State under President Robertson, was widely respected by Former Senate colleagues and considered a bright, thoughtful thinker as well as politician. On the other end was Newt Gingrich. No one could deny Gingrich was smart, but he was smart in the mold of Lee Atwater, a cunning, Machiavellian archconservative. Where Domenici was a patrician debater, Gingrich was a streetfighter. The campaign was bloody, and pit those broadly supportive of the President against those that opposed him, and, in a sense, rather than casting votes for Domenici- or Gingrich-pledged delegates, primary-goers felt as if they were casting votes for or against the current administration. In the end, Domenici and the compassionate conservatives won out. The battle against Gingrich and Mecham was hard and bloody, but the American voters had by and large rejected the dominionism and the strongman politics of the 1990s.

Seeking to unite the party, Domenici selected Illinois Congressman and former Gingrich ally Dennis Hastert as his running-mate. Domenici’s acceptance speech instantly made its way into political history: in it he masterfully decried the Robertson administration without mentioning the President by name. A call to reclaim the party from “despots and those that seek to curb freedom” and go on a path towards a compassionate conservatism gave Domenici a serious post-Convention bump as it became clear he was drawing a distinction between a future administration he would head up and the current one.

Of course, talk of unity was of no use if it remained talk. Famously, President Robertson, Vice President Gingrich, and Senator Mecham failed to attend the Convention, held in Dallas. Mecham’s delegates did turn up to vote for “Ev” and cast a scattering of votes for Vice President, many for First Lady Adelia Robertson, whose cache among the right had increased immeasurably after her lawsuit against Spitting Image America (which had also made quite the mockery of Evan Mecham’s presidential campaign) Gingrich's backers still hoped the wily Georgian had a shot at the White House and began a campaign to write in his name in the Independent Republican mail-in preference poll or, if need be, get him ballot access as an independent

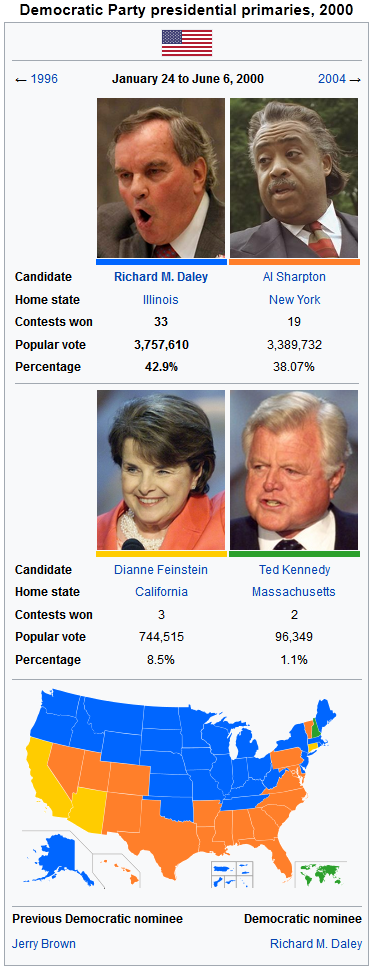

The 2000 Democratic primaries were an exercise in what not to do. Coming into 2000, the Democrats were in bad shape. The party had suffered staggering losses in recent elections, but that would all turn around if the Democrats chose the right man party leaders thought. Ted Kennedy was that man, many Democrats thought. Ted Kennedy could position himself as a successor to his elder brother and the prosperous, glamorous days of Camelot. Even if the Senator from Massachusetts had been involved with a car accident decades before, the American people would hunger for someone that harkened back to the days before the United States was embroiled in destructive wars in Iraq and Libya and had five·parties represented in Congress. As expected, Kennedy entered the race early on with a speech promising good times ahead on the steps of Faneuil Hall in Boston. Out of deference to his fellow Massachusettsite, Paul Tsongas, often speculated to be a possible contender, declined to run and endorsed Kennedy fairly early on.

The other major contenders, everyone thought, were California Governor Dianne Feinstein and the Reverend Al Sharpton. Feinstein had unseated Pete Wilson in 1994, not a strong year for Democrats, on an anti-Robertson platform and had won re-election in 1998. The Feinstein campaign was, however, a bit disjointed. She ran as a latte liberal, in favor of social liberalism, but also the creation of positive relations around the Pacific Rim and a shift away from protectionism and for fair-trade agreements with nations she had dealt with as Governor of California (China, Japan, South Korea, Mexico) Perhaps it was her status as a woman, or that she had previously served as Mayor of San Francisco, but whatever it was, Feinstein was unable to gather a significant following outside of California and certain suburban communities. Al Sharpton may not have had appeal to all segments of the Democratic Party, but in the African-American community (which was increasingly dominant within the Democratic Party), he was very popular. Sharpton had his first taste of politics in 1969 when Jesse Jackson appointed him as the youth director of the economic development campaign Operation Breadbasket. Sharpton’s 2000 run was, essentially, a rehashing of Jesse Jackson’s campaigns twelve and sixteen years before. However, times had changed. The Black Great Awakening had come, despite the Robertson years. Preachers like T.D. Jakes and Rosey Grier crisscrossed the country, spreading their message of fiery social conservatism with an African-American twist. Many of the facets of traditional African-American Christianity had been retained while fire and brimstone-esque evangelism had overrun many churches. The popular black ministers of 2000 were very different from those of, say, 1988. From the pulpit came denunciations of homosexuality, drug use, adultery and sexual topics in popular music. To be sure, there were still numerous liberal African-American ministers. Jesse Jackson still preached the equality of all people, gay and straight, black and white, disabled and fully abled.

Pat Schroeder, a Colorado Representative since 1973 with ties to Gary Hart and a sharp wit (that had been unleashed upon her nemeses Jack Fellure and Duke Cunningham several times on the House Floor) hoped to appeal to women and ran on anti-war platform broadly critical of the military-industrial complex. Another House Democrat, but on the opposite end of the political spectrum, a Virginian named Virgil Goode also threw his hat into the ring. A conservative strongly supportive of gun rights and opposition to regulation of the tobacco industry yet in favor of the Equal Rights Amendment and union labor, Goode was an enigma for who the fact he was still a Democrat could only be chalked up to the party being too weak to afford kicking him out or seriously reprimanding him. The focus of Goode’s candidacy was more or less a return to the New Deal coalition, but allegations of racism and bigotry dogged the Virginian that were severely harmful in the increasingly non-white Democratic primaries. Another white Southerner, Former Florida Governor and Senator Bob Graham entered the race. Graham had the benefit of being scandal-free, relatively moderate, anti-war, and pro-environment, yet he simply never got much traction. Graham withdrew before the first primaries were even held, recognizing from abysmal polling numbers that his campaign was doomed.

Finally, there was the dark horse, Chicago Mayor Richard M. Daley. Daley’s platform was pro-urban and strongly in favor of gun control, yet some of the social liberalism that might have accompanied a Daley run ten years earlier had disappeared as Daley played to his African-American constituents. Of course, constant allegations of corruption followed Daley wherever he went, but he held popularity in many urban centers for his strong record in Chicago. Many Rust Belt whites that had shifted away from the Democrats since 1992 were intrigued by a Daley candidacy.

Then came the primaries. Common knowledge dictated that the presumptive frontrunner, Ted Kennedy, would take Iowa, but on January 24th Richard Daley of all people came up on top in the caucuses. But that was just a hiccup, right? Kennedy could take New Hampshire for sure. And he did, but just barely. Sharpton and Daley surged there while Feinstein had support in some bedroom communities leaving Kennedy with a victory much smaller than expected and certainly not one that the frontrunner should be getting. A tearful Kennedy announced he was dropping out on February 2nd (Schroeder suspended her campaign the same day, but she was overshadowed by Kennedy and few noticed her departure) Kennedy also won the mail-in Democrats Abroad primary, but voting had begun in January and votes were not counted until April. Two ceremonial contests, Delaware and Washington, were held in February, but the month saw fierce, heavy campaigning between the remaining Democrats. On March 7th, the day Dianne Feinstein hoped would thrust her into frontrunner status, Sharpton and Daley actually managed to come out on top in most states with Feinstein only winning California, Arizona, and Connecticut. Then Dianne Feinstein dropped out (her campaign warchest was running dangerously low), which left only Sharpton, Daley, and Goode and none of these prospects especially thrilled the Democratic establishment.

Ted Kennedy pondered jumping back into the race, but ultimately decided against it. Would the base really vote for a man that had ruled out any further Presidential ambitions just a month before? Though Virgil Goode did pull in a number of votes, particularly in West Texas and East Tennessee, he was only relevant as a spoiler. Sharpton and Daley fought a particularly nasty campaign. Sharpton alleged Daley had not done enough for the African-American community in Chicago while Daley called Sharpton ‘a radical’ and ‘racial arsonist’ on numerous occasions. Contested primaries dragged into late May before Daley finally clinched the nomination.

Everyone was surprised when Daley announced Sharpton as his running-mate, but it did make some sense after all. Though there was residual animosity, the Daley/Sharpton ticket was nominated at the Democratic convention in late July. But that was not all. Some crafty journalists from Daley’s hometown of Chicago allegedly saw documents and receipts that indicated Sharpton had in fact bought his position on the Democratic ticket. Whether this was true was up for debate, but there were many that believed it could be true. Certainly there were other scandals Daley was caught up in, and it was under this dark cloud that Richard Daley and Al Sharpton marched forth as the unlikely standard bearers of the Democratic Party.

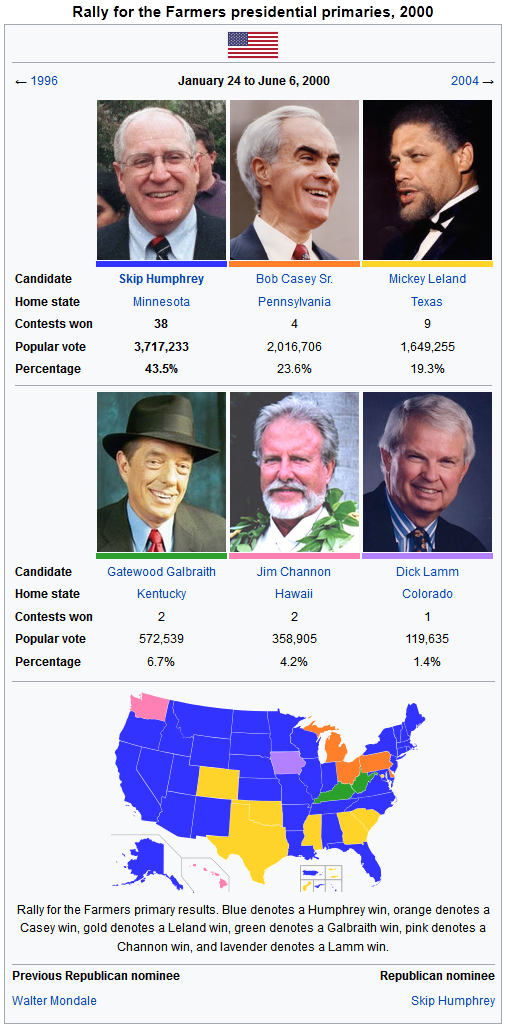

The Rally for the Farmers had high hopes in 2000. President Robertson’s approval rating was in the teens, and even most Republicans had deserted him, while those that didn’t appeared eager to tear the party apart if it nominated anyone that refused to worship the 42nd President. Into this environment, eight men declared their intention to run for the party nomination (actually, there were more, but they aren’t notable in any way)

The first to declare was Jim Channon, Governor of Hawaii. Channon had been the mastermind of the unused ‘First Earth Battalion’ proposal for the US Army in the early 1980s. Channon had since retired and made a name for himself as a New Age guru before surfacing in Hawaii to win election there. Channon’s Hawaii victory had partially been a result of a divided opposition, and nationally, calls for government research into the human potential movement and radical anti-monopoly stances were seen as too radical. In particular, one of the core principles of the campaign was a united humanity, something that, while intriguing and idealistic, was not even slightly feasible at the turn of the millennium. Channon’s early declaration and subsequent trips out of Hawaii for campaigning purposes angered some within the state, but in a sense, it was necessary for the Channon campaign as his name recognition was virtually zero and his policies extreme and in need of time to let voters think on them.

Channon was joined by a diverse group. From Texas came Former Chairman of the Congressional Black Caucus, Mickey Leland, a staunch liberal with an emphasis on foreign policy, especially where it intersected with human rights. Then there were the two Scranton boys - Senator Biden of Delaware and Representative Casey of Pennsylvania. While their upbringings may not have been as hard as they suggested, there was some truth to their image of hard-scrabble, working class, Roman Catholics. Casey was steadfastly pro-life and Biden usually voted that way as well. Both had similar bases and were appealing to Rust Belt whites, and the presence of two similar candidates in the race created some issues. From Minnesota came Governor Skip Humphrey, son of the 1968 Democratic nominee, and strong traditional progressive with a history of taking on the tobacco industry. Furthest to the right was Governor Fuqua of Florida, who had sat as a Democrat as early as 1963. Though something of a social conservative, Fuqua was strongly supportive of government involvement in the private sector, particularly in aerospace research (as he had once sat as head of the House Committee on Science, Space, and Technology) Of course no field would be complete without the outsiders. Dick Lamm, Democratic Governor of Colorado for twelve years from 1975 to 1987 (where his wife had been elected Governor in 1998) had made a return to politics in 1992 by being elected on the Rally line to Congress. Lamm had defied his party in Congress and had acquired a reputation for being difficult and hardheaded. While this did not endear Lamm to Party leadership, much of the Rally base was impressed by the results Lamm was able to deliver. Finally, the oddball: Former Kentucky Governor Gatewood Galbraith. Though Galbraith had served only one term as Governor of the Bluegrass State, he was something of a legend there since his 1987 run for Governor. He campaigned with a freewheeling style all his own and even appeared with Willie Nelson several times (the two had been close friends since the 1987 race) on a bizarre platform focused primarily on the return of America to an imagined pre-industrial past, where corporations were put in their place. In speeches, Galbraith harkened back to the Constitution frequently, and made the claim that recreational marijuana was legal under the Fourth Amendment. Another tendency of the campaign was to open rallies with local musicians’ renditions of the protest song Joe Hill. Though Galbraith was popular within the Midwest, and in some ways a repeat of Jim Traficant four years earlier, he never managed to get much traction in other parts of the country.

The campaign season was brutal. The election appeared the Rally’s to win, and each candidate thought himself the most qualified to beat whoever came out as the Republican nominee. Debates, hosted by the party, were heated slugging matches. What 1999 did was weed out the bad candidates. Biden’s campaign, though many backed it, failed to gain popular support as the candidate tanked similarly to his 1988 run (partly, his poor 2000 showing can be put up to the fact that he had previously run for President as a Democrat) Galbraith, Lamm, and Fuqua both proved unable to capitalize nationally, but remained regional players. Channon’s New Age ideas were not especially popular, and a series of gaffes hurt him. In an infamous incident following pro-life activists appearing at a rally (Channon was an unabashedly pro-choice candidate), the Hawaii Governor proposed establishing a party paramilitary, the Nā Kiaʻi polū (Hawaiian for ‘Blue Guard’) Statements like this and attacks referencing Channon’s First Earth Battalion Proposal slowly eroded his support, and much of the country came to view him as a crackpot. In this setting Humphrey, Leland, and Casey became the top three contenders. All three were staunch progressives and backed fairly extensive expansions of welfare programs and farming subsidies, though differed on social issues and foreign policy.

The Iowa Caucus, first contest in the nation (it had jumped in front of Ohio, much to the ire of Buckeye State Rallyites) was won in a landslide by Dick Lamm. While 36% of the vote does not seem like especially much, it was a considerable victory in a field with seven other candidates. However, this victory proved pyrrhic as Lamm faltered in the next few contests. Humphrey came out on top in New Hampshire and then Casey in Delaware (Biden had dropped out immediately after Iowa results showed he had been overwhelmingly rejected, but his endorsement of Casey had brought his fellow Scrantonian victory) The Ohio Primary, held on February 8th, was won in an upset by Casey. Seeing the writing on the wall, Lamm and Fuqua dropped out reducing the race to the three pre-primary frontrunners and Galbraith and Channon. Humphrey’s superior ground game and extensive network across the country slowly came to dominate the campaign. Casey and Leland scored several more victories, including the delegate-rich states of Pennsylvania, Texas, and Michigan, but both candidates had left the race and endorsed Humphrey by the end of March leaving the Minnesota Governor as the nominee-apparent. Galbraith defiantly declared that he would fight until the convention while Channon’s campaign simply fizzled out. Galbraith did manage to pull in Kentucky and West Virginia as voters there protested Humphrey, but he had very little popular support going into the convention and Galbraith announced he was endorsing Humphrey on June 21st, just a week before the Convention.

Humphrey clearly wanted Casey as his running-mate, as there were concerns that Humphrey came off as too patrician and someone that could connect well with the working class rank-and-file of the party was needed. Humphrey extended an offer to Casey, but he was refused and Casey suggested his ally Biden be chosen instead. Though Humphrey and Biden were known for frosty exchanges on the campaign trail, Biden quickly accepted an offer.

The convention was a jubilant affair, and though segments of the activist wing moaned and groaned and even cast a few protest votes during the nomination of the Humphrey/Biden ticket. The platform voted for was very liberal in some regards: the Equal Rights Amendment would be passed and the Flag Burning Amendment would be repealed while American troops would be withdrawn (or an agreement would be reached) from Iraq and Libya within three years. This brought further groans from the conservatives within the party, but they were placated by a firm commitment to farming subsidies, rural development, and a tacit concession that any attempts to restore abortion rights would not be too far-reaching and would not aim for full legalization. Besides, even if Skip Humphrey wanted to legalize flag burning he still was personally against it and he wasn’t a Robertsonite. Humphrey and Biden knew full well this was their election to win, and came swinging immediately out of the convention.

It took several years for real problems to arise. Less oversight meant Robertson had an increasing number of embarrassing gaffes,some highly offensive and alienating and authorized some politically poor decisions like the Invasion of Libya, and the natural conclusion of some of the President’s better initiatives, like Branstad v. Planned Parenthood put liberals on the back foot and ready to fight. Unfortunately, all this coincided with the Rally for the Farmers fully supplanting the Democrats and therefore providing an effective opposition to Robertson and Congressional Republicans.

Seeing this, much of the Republican Party shifted away from Robertson and though they resisted the calls for impeachment, they effectively made him a lame-duck President from 1999 onwards. Of course, there were those that still firmly backed Pat Robertson: Senators Evan Mecham of Arizona as well as Helms and East of North Carolina and the ultraconservative Jack Fellure of West Virginia’s Third district.

Two unabashedly Robertsonite major candidates filed (though only one would gain any traction): the aforementioned Senator Mecham and Former Secretary of Housing and Urban Development Morry Taylor, who had served from 1993 to 1997. Mecham had significant baggage: he had referred to African American children as “pickaninnies” and had claimed that America was a Christian nation and therefore Muslims and Jews (though he later strongly retracted the second part of this statement) were ineligible for public office. Mecham appropriated the name of a song penned to satirize him in the 1980s while he was Governor of Arizona, “You Can Call Me Ev” as a campaign slogan intended to evoke a folksy image. Taylor, nicknamed “The Grizz”, is a selfmade millionaire who took a single factory into an international tire business. While Taylor has never held elected office, he avoided many of the blunders that plagued Mecham. Taylor ran a much more economically-focused campaign, portraying himself as a successful businessman that would cut down on waste in the federal government. While Taylor his backers, he was unable to gain serious support, even in his home state of Iowa.

The two main contenders, however, were Vice President Gingrich and Former Secretary of State Pete Domenici. Gingrich, House Republican Whip before he was tapped to fill the assassinated Vice President Heinz’s shoes, was the attack dog of the Republican Party. Speaker Cheney was the respectable, public face of the House Republicans while Gingrich viciously blasted liberals inside and outside of the party. Gingrich toed a strong socially and fiscally conservative line and was the President’s number one man in the House, but that began to change after Gingrich became Vice President. Gingrich may have been an ideologue, but he could tell when a ship was sinking, so he began distancing himself from the Robertson administration in 1997. Gingrich’s appointment had effectively started a war between the Georgian and Domenici. As early as election night 1996, it was clear in Republican circles that Domenici wanted (and would likely get) the nod in 2000. Gingrich’s appointment and leaked statements from the Oval Office infuriated Domenici, who came to believe that Gingrich was Robertson’s favorite. Domenici himself became something of a critic of Pat Robertson during that administration’s last days in office. Though Pete Domenici was a conservative in most matters, he was uncomfortable with the extreme rhetoric from the White House, which was something that prompted him to resign from the State Department in February 1997. Domenici and Gingrich traded shots as early as 1998, two years before the Presidential election.

But of course, there were more. Former Representative Jack Kemp (who had come second in the 1992 primaries) entered the fray. Kemp had transformed during the Robertson years. He had served in Congress until 1994, but declined to run again that year. Since then, Kemp had shifted leftward on some social issues and had become what might be called a libertarian. There was also West Virginia Governor John Raese. Raese touted success in keeping the struggling West Virginia coal industry alive and compromise with the significant Democratic and then Rallyite state legislative delegations. While personally supportive of Robertson, Raese knew that his path to victory would require a less enthusiastic tone towards the President, and attempted to lie low on that subject. But one could not forget Wesley Clark. Clark, at 55 had never held elected office, but was a General in the US Army and a decorated combat veteran. Clark had served in Vietnam, where he was awarded the Silver Star, and then during the Invasion of Iraq. But Clark’s fame came from the Invasion of Libya, in which he was the Supreme Commander of Allied forces. In a masterful campaign, Libya fell within three weeks with few casualties during the initial invasion (though many would die in the subsequent occupation) Despite this, Clark was recalled to Washington on the orders of Pat Robertson himself, and Clark had been mustered out by the end of 1998. His Presidential campaign started barely six months later, in June of 1999. Clark portrayed himself as the national security candidate, and touted his ability to hold together the frayed Anglo-American Alliance in the recent Middle Eastern conflicts.

The campaigning season brought some surprises. Though on paper Wesley Clark was a solid candidate, he proved gaffe-prone. Advocating for internment camps on American soil turned many off to a Clark candidacy and suggesting the military have more of a role in American decision-making. Everyone knew Evan Mecham was a wildcard and prone to bizarre stunts, but his meeting with Canadian Regional Congress electoral alliance leader John Turmel was totally expected. Immediately, Democrats, the Rally, the American foreign service community, establishment Republicans, and even conservatives that realized talking to the leaders of secessionist groups in neighboring countries is not a good idea howled protest (a Senate censure failed to take the wind out of the Mecham campaign’s sails and, indeed might have helped him in some quarters)

Domenici came out on top in the Alaska Caucuses, but with no delegates assigned, it was a only a moral victory for the former Secretary of State’s camp. Domenici took Iowa that same day in a convincing victory. A week later, backed by Gordon Humphrey, Bob Smith, and Meldrim Thomson, Mecham scored a modest victory in the New Hampshire primary. Taylor and Kemp, whose campaigns hinged on upsets in Iowa and New Hampshire respectively, dropped out without endorsing any other candidate. The optimism among conservatives following Mecham’s New Hampshire victory proved misplaced as Domenici took Delaware and Gingrich South Carolina the next week. Mecham’s campaign simply had not put enough resources into the south, where favorite son Newt Gingrich was still popular. The New Hampshire upset could be ascribed to a favorable environment and lack of any candidates hailing from the region (aside from Jack Kemp, of course) Raese even picked up North Dakota before dropping out from a lack of funds (and just in time to return to West Virginia and file to run for a second term as Governor) Wesley Clark saw an upset in Washington, but all this was too little and too late as the showdown between Pete Domenici and Newt Gingrich, something both candidates had prepared for since 1998, began.

In a sense, the Domenici-Gingrich fight was one for the very heart of the GOP. Domenici, despite his service as Secretary of State under President Robertson, was widely respected by Former Senate colleagues and considered a bright, thoughtful thinker as well as politician. On the other end was Newt Gingrich. No one could deny Gingrich was smart, but he was smart in the mold of Lee Atwater, a cunning, Machiavellian archconservative. Where Domenici was a patrician debater, Gingrich was a streetfighter. The campaign was bloody, and pit those broadly supportive of the President against those that opposed him, and, in a sense, rather than casting votes for Domenici- or Gingrich-pledged delegates, primary-goers felt as if they were casting votes for or against the current administration. In the end, Domenici and the compassionate conservatives won out. The battle against Gingrich and Mecham was hard and bloody, but the American voters had by and large rejected the dominionism and the strongman politics of the 1990s.

Seeking to unite the party, Domenici selected Illinois Congressman and former Gingrich ally Dennis Hastert as his running-mate. Domenici’s acceptance speech instantly made its way into political history: in it he masterfully decried the Robertson administration without mentioning the President by name. A call to reclaim the party from “despots and those that seek to curb freedom” and go on a path towards a compassionate conservatism gave Domenici a serious post-Convention bump as it became clear he was drawing a distinction between a future administration he would head up and the current one.

Of course, talk of unity was of no use if it remained talk. Famously, President Robertson, Vice President Gingrich, and Senator Mecham failed to attend the Convention, held in Dallas. Mecham’s delegates did turn up to vote for “Ev” and cast a scattering of votes for Vice President, many for First Lady Adelia Robertson, whose cache among the right had increased immeasurably after her lawsuit against Spitting Image America (which had also made quite the mockery of Evan Mecham’s presidential campaign) Gingrich's backers still hoped the wily Georgian had a shot at the White House and began a campaign to write in his name in the Independent Republican mail-in preference poll or, if need be, get him ballot access as an independent

The 2000 Democratic primaries were an exercise in what not to do. Coming into 2000, the Democrats were in bad shape. The party had suffered staggering losses in recent elections, but that would all turn around if the Democrats chose the right man party leaders thought. Ted Kennedy was that man, many Democrats thought. Ted Kennedy could position himself as a successor to his elder brother and the prosperous, glamorous days of Camelot. Even if the Senator from Massachusetts had been involved with a car accident decades before, the American people would hunger for someone that harkened back to the days before the United States was embroiled in destructive wars in Iraq and Libya and had five·parties represented in Congress. As expected, Kennedy entered the race early on with a speech promising good times ahead on the steps of Faneuil Hall in Boston. Out of deference to his fellow Massachusettsite, Paul Tsongas, often speculated to be a possible contender, declined to run and endorsed Kennedy fairly early on.

The other major contenders, everyone thought, were California Governor Dianne Feinstein and the Reverend Al Sharpton. Feinstein had unseated Pete Wilson in 1994, not a strong year for Democrats, on an anti-Robertson platform and had won re-election in 1998. The Feinstein campaign was, however, a bit disjointed. She ran as a latte liberal, in favor of social liberalism, but also the creation of positive relations around the Pacific Rim and a shift away from protectionism and for fair-trade agreements with nations she had dealt with as Governor of California (China, Japan, South Korea, Mexico) Perhaps it was her status as a woman, or that she had previously served as Mayor of San Francisco, but whatever it was, Feinstein was unable to gather a significant following outside of California and certain suburban communities. Al Sharpton may not have had appeal to all segments of the Democratic Party, but in the African-American community (which was increasingly dominant within the Democratic Party), he was very popular. Sharpton had his first taste of politics in 1969 when Jesse Jackson appointed him as the youth director of the economic development campaign Operation Breadbasket. Sharpton’s 2000 run was, essentially, a rehashing of Jesse Jackson’s campaigns twelve and sixteen years before. However, times had changed. The Black Great Awakening had come, despite the Robertson years. Preachers like T.D. Jakes and Rosey Grier crisscrossed the country, spreading their message of fiery social conservatism with an African-American twist. Many of the facets of traditional African-American Christianity had been retained while fire and brimstone-esque evangelism had overrun many churches. The popular black ministers of 2000 were very different from those of, say, 1988. From the pulpit came denunciations of homosexuality, drug use, adultery and sexual topics in popular music. To be sure, there were still numerous liberal African-American ministers. Jesse Jackson still preached the equality of all people, gay and straight, black and white, disabled and fully abled.

Pat Schroeder, a Colorado Representative since 1973 with ties to Gary Hart and a sharp wit (that had been unleashed upon her nemeses Jack Fellure and Duke Cunningham several times on the House Floor) hoped to appeal to women and ran on anti-war platform broadly critical of the military-industrial complex. Another House Democrat, but on the opposite end of the political spectrum, a Virginian named Virgil Goode also threw his hat into the ring. A conservative strongly supportive of gun rights and opposition to regulation of the tobacco industry yet in favor of the Equal Rights Amendment and union labor, Goode was an enigma for who the fact he was still a Democrat could only be chalked up to the party being too weak to afford kicking him out or seriously reprimanding him. The focus of Goode’s candidacy was more or less a return to the New Deal coalition, but allegations of racism and bigotry dogged the Virginian that were severely harmful in the increasingly non-white Democratic primaries. Another white Southerner, Former Florida Governor and Senator Bob Graham entered the race. Graham had the benefit of being scandal-free, relatively moderate, anti-war, and pro-environment, yet he simply never got much traction. Graham withdrew before the first primaries were even held, recognizing from abysmal polling numbers that his campaign was doomed.

Finally, there was the dark horse, Chicago Mayor Richard M. Daley. Daley’s platform was pro-urban and strongly in favor of gun control, yet some of the social liberalism that might have accompanied a Daley run ten years earlier had disappeared as Daley played to his African-American constituents. Of course, constant allegations of corruption followed Daley wherever he went, but he held popularity in many urban centers for his strong record in Chicago. Many Rust Belt whites that had shifted away from the Democrats since 1992 were intrigued by a Daley candidacy.

Then came the primaries. Common knowledge dictated that the presumptive frontrunner, Ted Kennedy, would take Iowa, but on January 24th Richard Daley of all people came up on top in the caucuses. But that was just a hiccup, right? Kennedy could take New Hampshire for sure. And he did, but just barely. Sharpton and Daley surged there while Feinstein had support in some bedroom communities leaving Kennedy with a victory much smaller than expected and certainly not one that the frontrunner should be getting. A tearful Kennedy announced he was dropping out on February 2nd (Schroeder suspended her campaign the same day, but she was overshadowed by Kennedy and few noticed her departure) Kennedy also won the mail-in Democrats Abroad primary, but voting had begun in January and votes were not counted until April. Two ceremonial contests, Delaware and Washington, were held in February, but the month saw fierce, heavy campaigning between the remaining Democrats. On March 7th, the day Dianne Feinstein hoped would thrust her into frontrunner status, Sharpton and Daley actually managed to come out on top in most states with Feinstein only winning California, Arizona, and Connecticut. Then Dianne Feinstein dropped out (her campaign warchest was running dangerously low), which left only Sharpton, Daley, and Goode and none of these prospects especially thrilled the Democratic establishment.

Ted Kennedy pondered jumping back into the race, but ultimately decided against it. Would the base really vote for a man that had ruled out any further Presidential ambitions just a month before? Though Virgil Goode did pull in a number of votes, particularly in West Texas and East Tennessee, he was only relevant as a spoiler. Sharpton and Daley fought a particularly nasty campaign. Sharpton alleged Daley had not done enough for the African-American community in Chicago while Daley called Sharpton ‘a radical’ and ‘racial arsonist’ on numerous occasions. Contested primaries dragged into late May before Daley finally clinched the nomination.

Everyone was surprised when Daley announced Sharpton as his running-mate, but it did make some sense after all. Though there was residual animosity, the Daley/Sharpton ticket was nominated at the Democratic convention in late July. But that was not all. Some crafty journalists from Daley’s hometown of Chicago allegedly saw documents and receipts that indicated Sharpton had in fact bought his position on the Democratic ticket. Whether this was true was up for debate, but there were many that believed it could be true. Certainly there were other scandals Daley was caught up in, and it was under this dark cloud that Richard Daley and Al Sharpton marched forth as the unlikely standard bearers of the Democratic Party.

The Rally for the Farmers had high hopes in 2000. President Robertson’s approval rating was in the teens, and even most Republicans had deserted him, while those that didn’t appeared eager to tear the party apart if it nominated anyone that refused to worship the 42nd President. Into this environment, eight men declared their intention to run for the party nomination (actually, there were more, but they aren’t notable in any way)

The first to declare was Jim Channon, Governor of Hawaii. Channon had been the mastermind of the unused ‘First Earth Battalion’ proposal for the US Army in the early 1980s. Channon had since retired and made a name for himself as a New Age guru before surfacing in Hawaii to win election there. Channon’s Hawaii victory had partially been a result of a divided opposition, and nationally, calls for government research into the human potential movement and radical anti-monopoly stances were seen as too radical. In particular, one of the core principles of the campaign was a united humanity, something that, while intriguing and idealistic, was not even slightly feasible at the turn of the millennium. Channon’s early declaration and subsequent trips out of Hawaii for campaigning purposes angered some within the state, but in a sense, it was necessary for the Channon campaign as his name recognition was virtually zero and his policies extreme and in need of time to let voters think on them.

Channon was joined by a diverse group. From Texas came Former Chairman of the Congressional Black Caucus, Mickey Leland, a staunch liberal with an emphasis on foreign policy, especially where it intersected with human rights. Then there were the two Scranton boys - Senator Biden of Delaware and Representative Casey of Pennsylvania. While their upbringings may not have been as hard as they suggested, there was some truth to their image of hard-scrabble, working class, Roman Catholics. Casey was steadfastly pro-life and Biden usually voted that way as well. Both had similar bases and were appealing to Rust Belt whites, and the presence of two similar candidates in the race created some issues. From Minnesota came Governor Skip Humphrey, son of the 1968 Democratic nominee, and strong traditional progressive with a history of taking on the tobacco industry. Furthest to the right was Governor Fuqua of Florida, who had sat as a Democrat as early as 1963. Though something of a social conservative, Fuqua was strongly supportive of government involvement in the private sector, particularly in aerospace research (as he had once sat as head of the House Committee on Science, Space, and Technology) Of course no field would be complete without the outsiders. Dick Lamm, Democratic Governor of Colorado for twelve years from 1975 to 1987 (where his wife had been elected Governor in 1998) had made a return to politics in 1992 by being elected on the Rally line to Congress. Lamm had defied his party in Congress and had acquired a reputation for being difficult and hardheaded. While this did not endear Lamm to Party leadership, much of the Rally base was impressed by the results Lamm was able to deliver. Finally, the oddball: Former Kentucky Governor Gatewood Galbraith. Though Galbraith had served only one term as Governor of the Bluegrass State, he was something of a legend there since his 1987 run for Governor. He campaigned with a freewheeling style all his own and even appeared with Willie Nelson several times (the two had been close friends since the 1987 race) on a bizarre platform focused primarily on the return of America to an imagined pre-industrial past, where corporations were put in their place. In speeches, Galbraith harkened back to the Constitution frequently, and made the claim that recreational marijuana was legal under the Fourth Amendment. Another tendency of the campaign was to open rallies with local musicians’ renditions of the protest song Joe Hill. Though Galbraith was popular within the Midwest, and in some ways a repeat of Jim Traficant four years earlier, he never managed to get much traction in other parts of the country.

The campaign season was brutal. The election appeared the Rally’s to win, and each candidate thought himself the most qualified to beat whoever came out as the Republican nominee. Debates, hosted by the party, were heated slugging matches. What 1999 did was weed out the bad candidates. Biden’s campaign, though many backed it, failed to gain popular support as the candidate tanked similarly to his 1988 run (partly, his poor 2000 showing can be put up to the fact that he had previously run for President as a Democrat) Galbraith, Lamm, and Fuqua both proved unable to capitalize nationally, but remained regional players. Channon’s New Age ideas were not especially popular, and a series of gaffes hurt him. In an infamous incident following pro-life activists appearing at a rally (Channon was an unabashedly pro-choice candidate), the Hawaii Governor proposed establishing a party paramilitary, the Nā Kiaʻi polū (Hawaiian for ‘Blue Guard’) Statements like this and attacks referencing Channon’s First Earth Battalion Proposal slowly eroded his support, and much of the country came to view him as a crackpot. In this setting Humphrey, Leland, and Casey became the top three contenders. All three were staunch progressives and backed fairly extensive expansions of welfare programs and farming subsidies, though differed on social issues and foreign policy.

The Iowa Caucus, first contest in the nation (it had jumped in front of Ohio, much to the ire of Buckeye State Rallyites) was won in a landslide by Dick Lamm. While 36% of the vote does not seem like especially much, it was a considerable victory in a field with seven other candidates. However, this victory proved pyrrhic as Lamm faltered in the next few contests. Humphrey came out on top in New Hampshire and then Casey in Delaware (Biden had dropped out immediately after Iowa results showed he had been overwhelmingly rejected, but his endorsement of Casey had brought his fellow Scrantonian victory) The Ohio Primary, held on February 8th, was won in an upset by Casey. Seeing the writing on the wall, Lamm and Fuqua dropped out reducing the race to the three pre-primary frontrunners and Galbraith and Channon. Humphrey’s superior ground game and extensive network across the country slowly came to dominate the campaign. Casey and Leland scored several more victories, including the delegate-rich states of Pennsylvania, Texas, and Michigan, but both candidates had left the race and endorsed Humphrey by the end of March leaving the Minnesota Governor as the nominee-apparent. Galbraith defiantly declared that he would fight until the convention while Channon’s campaign simply fizzled out. Galbraith did manage to pull in Kentucky and West Virginia as voters there protested Humphrey, but he had very little popular support going into the convention and Galbraith announced he was endorsing Humphrey on June 21st, just a week before the Convention.

Humphrey clearly wanted Casey as his running-mate, as there were concerns that Humphrey came off as too patrician and someone that could connect well with the working class rank-and-file of the party was needed. Humphrey extended an offer to Casey, but he was refused and Casey suggested his ally Biden be chosen instead. Though Humphrey and Biden were known for frosty exchanges on the campaign trail, Biden quickly accepted an offer.

The convention was a jubilant affair, and though segments of the activist wing moaned and groaned and even cast a few protest votes during the nomination of the Humphrey/Biden ticket. The platform voted for was very liberal in some regards: the Equal Rights Amendment would be passed and the Flag Burning Amendment would be repealed while American troops would be withdrawn (or an agreement would be reached) from Iraq and Libya within three years. This brought further groans from the conservatives within the party, but they were placated by a firm commitment to farming subsidies, rural development, and a tacit concession that any attempts to restore abortion rights would not be too far-reaching and would not aim for full legalization. Besides, even if Skip Humphrey wanted to legalize flag burning he still was personally against it and he wasn’t a Robertsonite. Humphrey and Biden knew full well this was their election to win, and came swinging immediately out of the convention.

So what caused Biden to go Pro Life and Casey to not want to be Veep? I mean he was in good enough health to run for President, why would he not take the Veeps spot?

Oh God no. Please No.Seeking to unite the party, Domenici selected Illinois Congressman and former Gingrich ally Dennis Hastert as his running-mate.

Oh God no. Please No.

This is so going to end well (and by well, I mean horribly, of course)...

Im guessing it's setting up for a Victory by the RTF, considering both of their opponents VEEPs are just bad... AL Sharpton being easy to cast as a bomb throwing Radical and having a couple issues with Anti Semitism which will Haunt him and Dennis Hastersat being a Pedo, the RTF will be the only folks without a Veep problem.This is so going to end well (and by well, I mean horribly, of course)...

Bookmark1995

Banned

Im guessing it's setting up for a Victory by the RTF, considering both of their opponents VEEPs are just bad... AL Sharpton being easy to cast as a bomb throwing Radical and having a couple issues with Anti Semitism which will Haunt him and Dennis Hastersat being a Pedo, the RTF will be the only folks without a Veep problem.

Ol' Pat himself can be called "President Baggage."

Gentleman Biaggi

Banned

Wasn’t Jesse Jackson the one with the anti-Semitic quotes?Im guessing it's setting up for a Victory by the RTF, considering both of their opponents VEEPs are just bad... AL Sharpton being easy to cast as a bomb throwing Radical and having a couple issues with Anti Semitism which will Haunt him and Dennis Hastersat being a Pedo, the RTF will be the only folks without a Veep problem.

So what caused Biden to go Pro Life and Casey to not want to be Veep?

I mean Biden's voting record on it was quite mixed in the Senate, especially pre-2000 - for instance he (IIRC) opposed government funding of abortion and opposed partial-birth abortion, which is comparatively moderate or even conservative compared to the general mood within the party.

Wasn’t Jesse Jackson the one with the anti-Semitic quotes?

I know nothing about Sharpton, but Jackson definitely had anti-Semitic quotes. Didn't help that he was defended by Louis Farrakhan after those remarks were made.

Threadmarks

View all 25 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

1998 Downballot Results (Part 2) Where are they now? Things Fall Apart: 1999 2000 Major Party Nominations Mere Anarchy: 2000 Minor Party Nominations Religion and Politics in the 1990s Preview of 2000 Senate Elections The Second Coming: Election Day 2000

Share: