Chapter 17: Freedom's Home

Chapter 17: Freedom’s Home

Markos Botsaris Leads the Attack on Agrinion

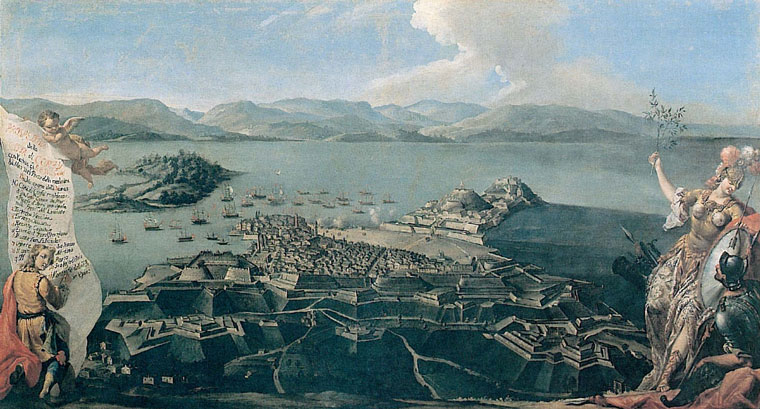

As the Egyptian Army of Ibrahim Pasha marched against Navarino, three Ottoman Armies began advancing south into Central Greece. The new Ottoman Serasker Resid Mehmed Pasha embarked upon a large-scale offensive against the Greeks in Southern Rumelia in conjunction with Ibrahim Pasha’s attacks in the Morea. In the east, his deputies Aslan Bey and Osman Aga launched an attack against the Greeks in Phthiotis and Phocis respectively, while in the West, Resid Pasha would personally lead the offensive against Missolonghi for the third time.[1] Missolonghi, more than any city within Greece, had become a bastion of defiance, of resistance, and of liberty. Sultan Mahmud’s obsession towards the city leaned towards mania, to the point that should Resid Pasha fail to capture Missolonghi, then his life would be forfeit.

Clearly, wishing to save his own life, Resid Pasha made every effort to succeed where his predecessors failed. To do so he gathered the largest Ottoman Army yet to be sent into Greece, over 30,000 strong, along with Aslan Bey’s 7,000 and Osman Aga’s 5,000, and thousands of other support personal and laborers, this was to be the single largest operation of the war. Resid also insisted on launching the offensive in early Spring as opposed to the Fall, to avoid the storms that plagued the prior two siege attempts. Despite their superior numbers, the Ottomans managed to make surprisingly little progress towards achieving their goals. In the East, Aslan Bey was quickly bogged down on the coastal road near Agios Konstantinos, while his compatriot Osman Aga fared even worse, only managing to advance 20 miles south of Lamia before he too was stopped just short of the hamlet of Bralos. Resid did the worst of all however.

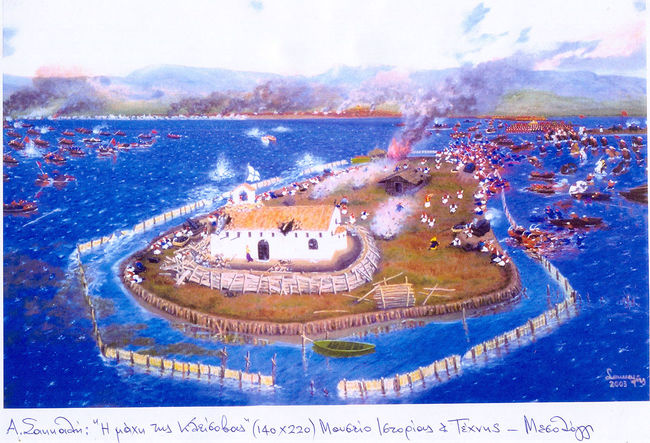

Beginning on the 12th of April 1825, Resid Pasha, like Omer Vrioni and Mustafa Pasha Bushatli before him, discovered the innate difficulty in assailing Missolonghi. The setting of the city remained unchanged, with the swamp to the east and the Lagoon to the West and South, the main difference lay in the landward wall and various fortifications across the lagoon which had been significantly reinforced since the previous attack in November 1823. Over 5,000 Greek soldiers, militiamen, and klephts had gathered to defend the “Sacred City”, with 3,000 men in Missolonghi proper, 1,000 in Anatolikon, another 1,000 protecting the surrounding villages, islands, and sandbanks in the area. The city also boasted a contingent of Italian and German Philhellenes, veterans of the Napoleonic wars, trained in modern military tactics, and equipped with modern weapons, they posed a significant threat to the Ottoman forces.

Similarly, the mile-long land walls protecting Missolonghi had been improved as well. The height had been increased from 4ft in 1822 to nearly 10ft by the beginning of 1825, the width broadened from 2ft to nearly 5ft, and though it was still largely made of dirt and earth, brick and mortar had started to replace the earthen rampart in some areas.[2] Most impressively were the seventeen great bastions built into the wall by the engineer Michail Kokkinis. Each bastion was equipped with three of the town’s cannons and mortars, and each had been designed as triangular projections from the walls enabling the defenders to work in support of each other.

The Wall of Missolonghi

Most importantly, defense of the city, fell to the newly appointed Governor General of Western Greece, Markos Botsaris, whose skill and loyalty had been deftly rewarded. Still, Botsaris opted to remain in the hills striking at the exposed rear of the Ottomans as he had done in the prior to sieges, rather than lead the defense of Missolonghi from behind its walls. Instead, he left his uncle, Notis Botsaris as commander of the city’s defense, while Markos assumed command of the entire theater. Notis Botsaris, despite being an old klepht in his 60's, still proved to be a spry individual who drove a hard bargain with the Nafplion government, to wring every man, every gun, and every Piastre he could from the state for his garrison.

To combat the improved Greek defenses, Resid Pasha utilized a scheme of his own to overcome them. Greek slaves brought in from Macedonia and Thessaly were used to dig the trenches and build the mounds of the Ottoman siegeworks. In doing so, the defenders within Missolonghi were forced to choose between firing upon their own countrymen or risk the encroachment of the Ottoman trenches on their position. In some cases, the trenches reached within a hundred yards of Missolonghi’s walls, resulting in the exchange of banter between sides during the breaks in the attack. While Resid had many more men than his predecessors, he surprisingly lacked in artillery, bringing only three cannons with him in April and by the end of the Summer, this number had only risen to eighteen. Without any substantial artillery with which to force his way into Missolonghi, Resid was relegated to waiting the Greeks out through blockade and starvation.

Resid Pasha’s attempts to starve the Greeks into submission would prove to be a complete failure as the Ottoman Navy's blockade of Missolonghi proved to be a total farce. The Greek ships which had mutinied over the winter, returned to service at the insistence of the government in return for back pay and bonuses, and despite the improved naval acumen of the Turks since the opening months of the war, the Greeks still remained the masters of the sea.[3] The liberation of Nafpaktos has also denied the Ottomans of a strategic port with which to support the blockade, instead it aided the Greeks in breaking that same blockade as the Ottoman navy in the region was forced to operate solely from Patras, stretching its resources to the limit. As a result, Greek smugglers regularly broke through the Turkish few ships patrolling the lagoon’s entrance, carrying loads of maize and grain, bullets and powder into the Missolonghi. The supply situation in Missolonghi was made even easier by the evacuation of the women and children of Missolonghi to Cephalonia in anticipation of the looming battle.

Rather than sending his men to seize the islands in the lagoon, and tightening the blockade, Resid opted instead to waste many Ottoman lives conducting fruitless assaults against the reinforced walls of Missolonghi or attempting to cross the Eastern Swamp. As with the previous attempts to cross the marsh, the Ottomans quickly became encumbered by the thick mud, leaving hundreds of men as sitting targets for the Greeks and Philhellenes atop the walls of Missolonghi. The attack on the 10th of May was especially bloody, as from atop the walls of Missolonghi one could see dead and dying men as far as the eye could see.

With direct assaults against Missolonghi a failure, Resid turned towards sapping the wall around Missolonghi. Engineers and slaves were brought in to dig the tunnel beneath the Greek’s defenses. While the tunnel had been expertly crafted, the chamber had remained unsealed when they detonated their bomb, likely due to sabotage by the slaves. Rather than driving the blast upward as intended into the city, the opening allowed the explosion to flow back up the tunnel catching several poor Turks and Greek slaves in the process. Catching wind of the Turkish initiative, the Greeks, with the aid of the Philhellenes, began construction of their own tunnel, which met with more success than the Ottomans. Completed in September, the Greeks promptly detonated their own mine underneath the Turkish trenches. The rumble from the explosion was so great that the whole ground shook beneath their feet. Soon, arms and legs, guts and entrails, among a menagerie of other body parts rained down from the sky blanketing the field below in a grisly spectacle of blood.

Resid Pasha and the Explosion of the Greek Mine

By December, Resid was no closer to taking Missolonghi than he had been nearly 8 months prior. The coming of winter also signaled the start of the rainy season in Greece, making siege warfare an impossible task, as had been the case in the prior two attempts on Missolonghi. Resid, however, could not lift the siege, as that would invite his own demise at the hands of his irate Sultan. Instead, he chose to leave a small screening force behind to maintain the siege, while Resid and much of his army departed for winter quarters near Agrinion. This would prove to be his undoing.

The Greeks had been preparing their own attack against the Ottomans. Over the past few months, dispatches had been sent to Nafplion calling on reinforcements and additional forces to lift the siege, and while the Government agreed in part on the need for action, there was little they could do. Ibrahim was still loose in the Morea, with nearly the entire western half of the peninsula lost to him, and the offenses in Phocis and Phthiotis had managed some successes in the closing days of fall, advancing further south. The Government, despite these problems committed 1,000 men to aid Missolonghi, far shorter than the 8,000 requested.[4] Still it was better than nothing and with the withdraw of a large portion of the enemy force into Winter quarters, they were now free to commence their operation.

On the 11th of January 1826, members of the Missolonghi garrison traveled under the cover of darkness across the lagoon with the aid of the local fishermen, who promptly ferried nearly 2,000 of the cities garrison to a meeting point just north of Anatolikon. There they joined with Markos Botsaris and his Souliotes, Georgios Karaiskakis and his klephts, and the men dispatched by the Nafplion government. Making sure not to alert the Ottomans still outside Missolonghi, the Greeks made slow progress towards Agrinion where Resid and his main force were located. Unsuspecting of a Greek attack in the dead of winter, Resid Pasha had left his guard down, the lack of activity reported from his men at Missolonghi had loosened his watch. Arriving outside Agrinion on the 13th, the Greeks made ready to attack the Ottomans in the dead of night.

In the chaos that followed Resid was slain by a Souliot, bearing a close resemblance to Botsaris, when he exited from his tent, still wearing his nightgown and sleeping cap. The death of their commander sent the already demoralized and downtrodden Ottomans besieging Missolonghi into a tailspin. Many men began fleeing for the hills, most surrendered on the spot, but what was certain is that the fight left the Ottomans in that moment. Then only seconds later they regained it as 3,000 Egyptians rushed onto the field of Agrinion right into the rear of the Greek force.

The Vanguard of Ibrahim Pasha had arrived to reinforce the Ottoman siege effort at Missolonghi, too late to save Resid Pasha, but it arrived in time to save his army from complete annihilation. With the arrival of fresh reinforcements, the Ottomans quickly began to reorganize and fight off the Greeks who were themselves forced to retreat to Missolonghi, and barely two weeks later the Fourth Siege began.

Greece on the 13th of January 1826

Purple – Greece

Green – Ottoman Empire

Pink – The United States of the Ionian Islands

Next Time: Glory’s Grave

[1] The attacks by Aslan Bey and Osman Aga are diversionary attacks meant to draw attention away from Missolonghi.

[2] This reinforcement of the land wall was done at the insistence of Alexandros Mavrokordatos and Lord Byron both in OTL and in TTL. Sadly, most of the wall no longer exists due to the heavy damage it received during the war and modern develop in Missolonghi. The bastions of Missolonghi were originally named after famous revolutionaries like Benjamin Franklin, William of Orange, Skanderbeg, etc. Eventually though, these names were replaced by more generic titles like great bastion or Terrible, etc.

[3] The skill gap between the Ottoman navy and the Greek navy is closing, but it is still decidedly in the Greeks favor in 1825. The Ottomans also lack the naval bases from which to operate from. They do have Patras, Rio, and Antirrio, but Patras can only support so many ships and the latter two are essentially glorified fishing hovels with giant castles next to them.

[4] The defenders of Missolonghi in the OTL siege did indeed ask for help from the Greek Government. They initially planned to attack Resid’s force over the winter with the help of reinforcements from the Greek government, but nothing actually happened and by the time they could do something, Ibrahim Pasha arrived with his army. The Winter of 1825/1826 was arguably the best opportunity the Greeks had to break the Third Siege of Missolonghi, but they were in a terrible situation at that point with most of the Morea and Central Greece under Ottoman and Egyptian control by the start of 1826.

Markos Botsaris Leads the Attack on Agrinion

As the Egyptian Army of Ibrahim Pasha marched against Navarino, three Ottoman Armies began advancing south into Central Greece. The new Ottoman Serasker Resid Mehmed Pasha embarked upon a large-scale offensive against the Greeks in Southern Rumelia in conjunction with Ibrahim Pasha’s attacks in the Morea. In the east, his deputies Aslan Bey and Osman Aga launched an attack against the Greeks in Phthiotis and Phocis respectively, while in the West, Resid Pasha would personally lead the offensive against Missolonghi for the third time.[1] Missolonghi, more than any city within Greece, had become a bastion of defiance, of resistance, and of liberty. Sultan Mahmud’s obsession towards the city leaned towards mania, to the point that should Resid Pasha fail to capture Missolonghi, then his life would be forfeit.

Clearly, wishing to save his own life, Resid Pasha made every effort to succeed where his predecessors failed. To do so he gathered the largest Ottoman Army yet to be sent into Greece, over 30,000 strong, along with Aslan Bey’s 7,000 and Osman Aga’s 5,000, and thousands of other support personal and laborers, this was to be the single largest operation of the war. Resid also insisted on launching the offensive in early Spring as opposed to the Fall, to avoid the storms that plagued the prior two siege attempts. Despite their superior numbers, the Ottomans managed to make surprisingly little progress towards achieving their goals. In the East, Aslan Bey was quickly bogged down on the coastal road near Agios Konstantinos, while his compatriot Osman Aga fared even worse, only managing to advance 20 miles south of Lamia before he too was stopped just short of the hamlet of Bralos. Resid did the worst of all however.

Beginning on the 12th of April 1825, Resid Pasha, like Omer Vrioni and Mustafa Pasha Bushatli before him, discovered the innate difficulty in assailing Missolonghi. The setting of the city remained unchanged, with the swamp to the east and the Lagoon to the West and South, the main difference lay in the landward wall and various fortifications across the lagoon which had been significantly reinforced since the previous attack in November 1823. Over 5,000 Greek soldiers, militiamen, and klephts had gathered to defend the “Sacred City”, with 3,000 men in Missolonghi proper, 1,000 in Anatolikon, another 1,000 protecting the surrounding villages, islands, and sandbanks in the area. The city also boasted a contingent of Italian and German Philhellenes, veterans of the Napoleonic wars, trained in modern military tactics, and equipped with modern weapons, they posed a significant threat to the Ottoman forces.

Similarly, the mile-long land walls protecting Missolonghi had been improved as well. The height had been increased from 4ft in 1822 to nearly 10ft by the beginning of 1825, the width broadened from 2ft to nearly 5ft, and though it was still largely made of dirt and earth, brick and mortar had started to replace the earthen rampart in some areas.[2] Most impressively were the seventeen great bastions built into the wall by the engineer Michail Kokkinis. Each bastion was equipped with three of the town’s cannons and mortars, and each had been designed as triangular projections from the walls enabling the defenders to work in support of each other.

The Wall of Missolonghi

Most importantly, defense of the city, fell to the newly appointed Governor General of Western Greece, Markos Botsaris, whose skill and loyalty had been deftly rewarded. Still, Botsaris opted to remain in the hills striking at the exposed rear of the Ottomans as he had done in the prior to sieges, rather than lead the defense of Missolonghi from behind its walls. Instead, he left his uncle, Notis Botsaris as commander of the city’s defense, while Markos assumed command of the entire theater. Notis Botsaris, despite being an old klepht in his 60's, still proved to be a spry individual who drove a hard bargain with the Nafplion government, to wring every man, every gun, and every Piastre he could from the state for his garrison.

To combat the improved Greek defenses, Resid Pasha utilized a scheme of his own to overcome them. Greek slaves brought in from Macedonia and Thessaly were used to dig the trenches and build the mounds of the Ottoman siegeworks. In doing so, the defenders within Missolonghi were forced to choose between firing upon their own countrymen or risk the encroachment of the Ottoman trenches on their position. In some cases, the trenches reached within a hundred yards of Missolonghi’s walls, resulting in the exchange of banter between sides during the breaks in the attack. While Resid had many more men than his predecessors, he surprisingly lacked in artillery, bringing only three cannons with him in April and by the end of the Summer, this number had only risen to eighteen. Without any substantial artillery with which to force his way into Missolonghi, Resid was relegated to waiting the Greeks out through blockade and starvation.

Resid Pasha’s attempts to starve the Greeks into submission would prove to be a complete failure as the Ottoman Navy's blockade of Missolonghi proved to be a total farce. The Greek ships which had mutinied over the winter, returned to service at the insistence of the government in return for back pay and bonuses, and despite the improved naval acumen of the Turks since the opening months of the war, the Greeks still remained the masters of the sea.[3] The liberation of Nafpaktos has also denied the Ottomans of a strategic port with which to support the blockade, instead it aided the Greeks in breaking that same blockade as the Ottoman navy in the region was forced to operate solely from Patras, stretching its resources to the limit. As a result, Greek smugglers regularly broke through the Turkish few ships patrolling the lagoon’s entrance, carrying loads of maize and grain, bullets and powder into the Missolonghi. The supply situation in Missolonghi was made even easier by the evacuation of the women and children of Missolonghi to Cephalonia in anticipation of the looming battle.

Rather than sending his men to seize the islands in the lagoon, and tightening the blockade, Resid opted instead to waste many Ottoman lives conducting fruitless assaults against the reinforced walls of Missolonghi or attempting to cross the Eastern Swamp. As with the previous attempts to cross the marsh, the Ottomans quickly became encumbered by the thick mud, leaving hundreds of men as sitting targets for the Greeks and Philhellenes atop the walls of Missolonghi. The attack on the 10th of May was especially bloody, as from atop the walls of Missolonghi one could see dead and dying men as far as the eye could see.

With direct assaults against Missolonghi a failure, Resid turned towards sapping the wall around Missolonghi. Engineers and slaves were brought in to dig the tunnel beneath the Greek’s defenses. While the tunnel had been expertly crafted, the chamber had remained unsealed when they detonated their bomb, likely due to sabotage by the slaves. Rather than driving the blast upward as intended into the city, the opening allowed the explosion to flow back up the tunnel catching several poor Turks and Greek slaves in the process. Catching wind of the Turkish initiative, the Greeks, with the aid of the Philhellenes, began construction of their own tunnel, which met with more success than the Ottomans. Completed in September, the Greeks promptly detonated their own mine underneath the Turkish trenches. The rumble from the explosion was so great that the whole ground shook beneath their feet. Soon, arms and legs, guts and entrails, among a menagerie of other body parts rained down from the sky blanketing the field below in a grisly spectacle of blood.

Resid Pasha and the Explosion of the Greek Mine

By December, Resid was no closer to taking Missolonghi than he had been nearly 8 months prior. The coming of winter also signaled the start of the rainy season in Greece, making siege warfare an impossible task, as had been the case in the prior two attempts on Missolonghi. Resid, however, could not lift the siege, as that would invite his own demise at the hands of his irate Sultan. Instead, he chose to leave a small screening force behind to maintain the siege, while Resid and much of his army departed for winter quarters near Agrinion. This would prove to be his undoing.

The Greeks had been preparing their own attack against the Ottomans. Over the past few months, dispatches had been sent to Nafplion calling on reinforcements and additional forces to lift the siege, and while the Government agreed in part on the need for action, there was little they could do. Ibrahim was still loose in the Morea, with nearly the entire western half of the peninsula lost to him, and the offenses in Phocis and Phthiotis had managed some successes in the closing days of fall, advancing further south. The Government, despite these problems committed 1,000 men to aid Missolonghi, far shorter than the 8,000 requested.[4] Still it was better than nothing and with the withdraw of a large portion of the enemy force into Winter quarters, they were now free to commence their operation.

On the 11th of January 1826, members of the Missolonghi garrison traveled under the cover of darkness across the lagoon with the aid of the local fishermen, who promptly ferried nearly 2,000 of the cities garrison to a meeting point just north of Anatolikon. There they joined with Markos Botsaris and his Souliotes, Georgios Karaiskakis and his klephts, and the men dispatched by the Nafplion government. Making sure not to alert the Ottomans still outside Missolonghi, the Greeks made slow progress towards Agrinion where Resid and his main force were located. Unsuspecting of a Greek attack in the dead of winter, Resid Pasha had left his guard down, the lack of activity reported from his men at Missolonghi had loosened his watch. Arriving outside Agrinion on the 13th, the Greeks made ready to attack the Ottomans in the dead of night.

In the chaos that followed Resid was slain by a Souliot, bearing a close resemblance to Botsaris, when he exited from his tent, still wearing his nightgown and sleeping cap. The death of their commander sent the already demoralized and downtrodden Ottomans besieging Missolonghi into a tailspin. Many men began fleeing for the hills, most surrendered on the spot, but what was certain is that the fight left the Ottomans in that moment. Then only seconds later they regained it as 3,000 Egyptians rushed onto the field of Agrinion right into the rear of the Greek force.

The Vanguard of Ibrahim Pasha had arrived to reinforce the Ottoman siege effort at Missolonghi, too late to save Resid Pasha, but it arrived in time to save his army from complete annihilation. With the arrival of fresh reinforcements, the Ottomans quickly began to reorganize and fight off the Greeks who were themselves forced to retreat to Missolonghi, and barely two weeks later the Fourth Siege began.

Greece on the 13th of January 1826

Purple – Greece

Green – Ottoman Empire

Pink – The United States of the Ionian Islands

Next Time: Glory’s Grave

[1] The attacks by Aslan Bey and Osman Aga are diversionary attacks meant to draw attention away from Missolonghi.

[2] This reinforcement of the land wall was done at the insistence of Alexandros Mavrokordatos and Lord Byron both in OTL and in TTL. Sadly, most of the wall no longer exists due to the heavy damage it received during the war and modern develop in Missolonghi. The bastions of Missolonghi were originally named after famous revolutionaries like Benjamin Franklin, William of Orange, Skanderbeg, etc. Eventually though, these names were replaced by more generic titles like great bastion or Terrible, etc.

[3] The skill gap between the Ottoman navy and the Greek navy is closing, but it is still decidedly in the Greeks favor in 1825. The Ottomans also lack the naval bases from which to operate from. They do have Patras, Rio, and Antirrio, but Patras can only support so many ships and the latter two are essentially glorified fishing hovels with giant castles next to them.

[4] The defenders of Missolonghi in the OTL siege did indeed ask for help from the Greek Government. They initially planned to attack Resid’s force over the winter with the help of reinforcements from the Greek government, but nothing actually happened and by the time they could do something, Ibrahim Pasha arrived with his army. The Winter of 1825/1826 was arguably the best opportunity the Greeks had to break the Third Siege of Missolonghi, but they were in a terrible situation at that point with most of the Morea and Central Greece under Ottoman and Egyptian control by the start of 1826.

Last edited: