You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Pride Goes Before a Fall: A Revolutionary Greece Timeline

- Thread starter Earl Marshal

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 100 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 93: Mr. Smith goes to Athens Part 94: Twilight of the Lion King Part 95: The Coburg Love Affair Chapter 96: The End of the Beginning Chapter 97: A King of Marble Chapter 98: Kleptocracy Chapter 99: Captains of Industry Chapter 100: The Balkan LeagueDid you accidentally delete the rest of the postThank you very much! Speaking of Byron.

Chapter 11: The Baron Byron

Chapter 11: The Baron Byron

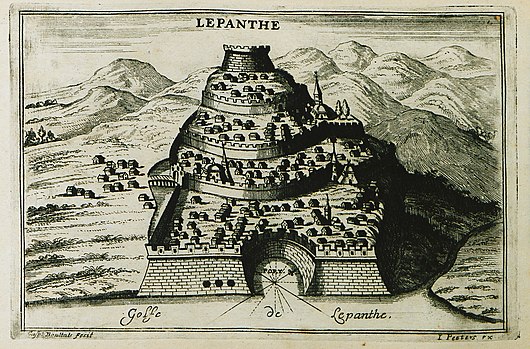

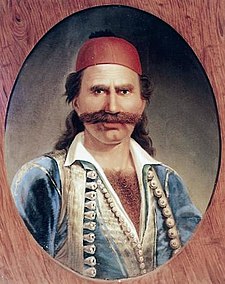

Lord George Gordon Byron, 6th Baron Byron, British Poet, and Philhellene

In many ways, 1823 ended the way it began, with the Ottomans withdrawing into Winter quarters after a failed assault on Missolonghi. In the East, the Ottomans had done little beyond the regular border raid into Boeotia, and at sea, the Ottoman fleet had been sent out under its third Kapudan Pasha in the past year, Khosref Pasha. Khosref Pasha, despite being a decadent old man more suited for the pleasures of retirement than the rigors of war, still managed to take the lessons of the last year to heart, trading the heavy Ships of the Line for more agile frigates, corvettes, and brigs widely used by the Greeks. Traveling to Evvia (Euboea), Khosref reinforced the Ottoman garrison of Karistos before making a supply run around the Morea. On his return to Constantinople in October his fleet was ambushed by the Greeks off the coast of Tenedos resulting in the capture of two corvettes and four brigs. While certainly embarrassing, this battle was not the worst mishap for the Ottoman Navy that year. No, that distinct dishonor fell to a particular naval engagement off the coast of Missolonghi that did not take place.

On the 29th of December, two ships flying the flag of the Ionian Islands departed from the port of Metaxa on the island of Cephalonia. The ships, a bombard and a mistico, were traveling for the city of Missolonghi carrying a cache of rifles, several horses, a few hunting dogs, and 25 passengers, with the most prominent being a British Peer intent on joining the fight in Greece. Immediately their crossing was beset by problems, the bombard being larger was quickly outpaced by the sleeker mistico, and by nightfall they had become completely seperated. There most trying episode came on the first night as the mistico soon ran afoul of a patrolling Ottoman Corvette. Panic gripped the passengers and crew as they quickly moved to destroy any incriminating evidence that might contradict their cover story that they were simply headed towards Kalamos for a hunting expedition. The lanterns were doused, the dogs were muzzled and the passengers hid themselves. When no response came from the boat, the Ottoman vessel began to pull alongside. Were it not for the sudden emergence of three Greek ships from the darkness causing the Ottoman vessel to flee, the ship would have likely been detained at Patras for days at the very least if not indefinitely. With the Ottoman ship in retreat, the Greeks moved alongside the small mistico, offering the ship safe passage to Missolonghi. Arriving on the 1st of January in the early morning, Lord Byron stepped ashore in Greece.[1]

Lord Byron, was one of thousands of Philhellenes from across Europe and the Americas who made their way to the Balkans to aid the Greeks over the course of the war. Many were soldier like Sir Richard Church, Charles Nicolas Fabvier, and Karl von Norman-Ehrenels who joined the Greeks as commanders on the field of battle. Others were diplomats like Viscount Stratford Canning and his cousin, the statesman George Canning who aided the Greeks from abroad with their diplomacy and politicking. Then there were artists like the painters Louis Dupre and Peter von Hess whose works of art galvanized the masses. Many chose to form groups with the express purpose of raising funds for the Greek state, the largest and most influential being the London Greek Committee of which Lord Byron was a prominent member.

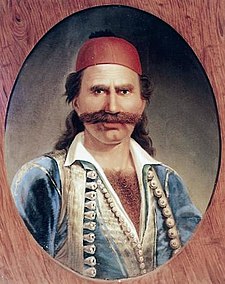

George Gordon Byron was the son of Captain John “Mad Jack” Byron of the Coldstream Guard and his wife, Lady Catherine Gordon of Gight. George, more commonly known as Lord Byron was the 6th Baron Byron of his family, a family with a long pedigree of accomplished scholars, soldiers, sailors, and poets. Despite being born into nobility, his childhood was hardly whimsical or luxurious. His father was an infamous debtor, one who squandered his wife’s fortune meeting his lavish expenses. Captain Byron was for all intents and purposes a bastard and a vagabond, who violently beat his first wife to the brink of death on many occasions and married his second wife, Catherine, solely for her extensive wealth. His excessive gambling drove Byron’s mother to depression and heavy bouts of drinking over her husband’s treatment of her and their son. It is fortunate for all involved that “Mad Jack” died in 1791 while overseas in Valenciennes, France.

Captain Jack Byron (Left) and Lady Catherine Gordon of Gight (Right)

Lord Byron’s troubles did not end there, however. He would prove himself to be quite unskilled as a scholar in his early years and he lacked the physical prowess of a military man due to a sickly constitution and a clubbed right foot. Due to his condition, he was regularly wracked with depression and prone to fits of anger. His only remarkable qualities seem to have been found in his mastery of the arts, specifically poetry. Byron had a way with words that made young maidens swoon, and grown men cry. His poetry tended to be the topic of conversation from the proper folk of British high society to the common man on the streets. To be referenced within any of his works was often considered a badge of honor whether it be for good or for ill.

Many of Byron’s poems were thinly veiled soliloquys of his own illustrious love life. Throughout his years, Lord Byron would have no less than six lovers and according to rumors he engaged in many more unrecorded affairs, with the most scandalous allegedly being an affair between Byron and his half-sister Augusta Leigh. His married life was not so successful, with two attempts ending in divorce. Byron has also had at least five confirmed children, both legitimate and out of wedlock. Byron was an eccentric fellow who on occasion dabbled in homosexual activities with his companions. Despite his many affairs, and numerous scandals in the name of romance, by far the greatest love of his life, however, were the lands of Italy and Greece. Like many he found these ancient lands to be intoxicating and romantic, filled with ideas of art, liberalism, philosophy, and romance. It was during his time on tour in Genoa, that war broke out in Greece and while he lacked in military experience or feats of strength he nevertheless found the conflict to be an exciting chance at adventure, carried out in pursuit of a noble cause. With all the gusto and extravagance of a nobleman and a poet, Byron left Italy to aid the Greeks in their effort.

Traveling first to the Ionian Island of Cephalonia where he would stay for nearly four months, Byron soon became inundated with letters from the many chief actors across Greece. Petros Mavromichalis invited him to Nafplion, Georgios Kountarious to Hydra, Odysseus Androutsos to Athens, and Alexandros Mavrokordatos to Missolonghi. Each called on Byron to join them and lend them his aid; though in truth each were thinly veiled ploys to gain access to his money and resources for their own personal ventures.[2] Despite the tenacity and vigor of these competitors it was his correspondence with the Souliot Markos Botsaris which finally drew Byron to Missolonghi, where he arrived on the 1st of January 1824. Barely halfway off the boat, Byron was immediately put to work. At the personal behest of Alexandros Mavrokordatos and Markos Botsaris, Byron was appointed to work on their latest endeavor, an assault on the strategically important town of Nafpaktos.

Byron arrives in Missolonghi

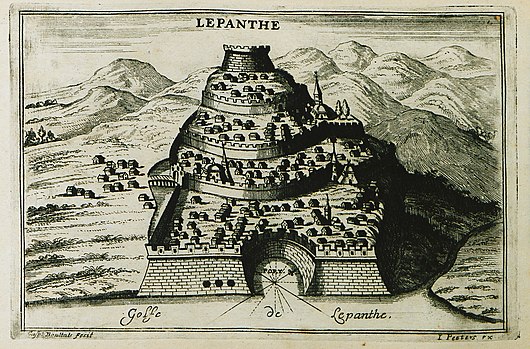

Nafpaktos, or Lepanto as the Venetians once called it, was founded along the northern littoral of the Gulf of Corinth 25 miles to the east of Missolonghi. Nafpaktos was a small town, with no more than 6,000 people most of whom fled at the onset of the war. Surrounded by impressive ramparts of Venetian design, Nafpaktos possessed one of finest natural harbors in all of Greece and its situation near the Gulf of Corinth made it a perfect refuge for Ottoman ships in the region. But it was Nafpaktos castle which was truly impressive, with its stout walls and imposing citadel it was a foreboding sight overlooking the harbor from its hill and as one of the largest fortifications in all of Greece, it made for an enticing target.

With Nafpaktos under their control, the Greeks believed they would roll up the remaining Ottoman possessions in the Gulf. 6 Miles to the West was the Castle of the Roumeli in Antirrio, and directly across the water was its counterpart, the Castle of the Morea and the small fishing hovel of Rio. To the West of Rio was the city of Patras and its mighty castle, making them the greatest remaining Ottoman possessions in the Morea. With Nafpaktos liberated, the castles of the Roumeli and the Morea, along with the city and citadel of Patras would be rendered indefensible forcing the Ottomans to abandon their remaining holdings on the Gulf, or risk the loss of several thousand soldiers and civilians.[3]

The outcome of the expedition was predicated upon the authenticity of recent reports which provided the Greeks with a decided advantage, but also a strict deadline. Word had emerged from within Nafpaktos that the Albanian garrison was on the verge of revolt. Having gone without proper pay for 18 months, and forced to man the castle well beyond their contracted terms of service, unrest had become understandably high among the Albanian mercenaries, and while it was not spoken aloud, in private they allegedly made threats announcing they would surrender the fortress to the Greeks if efforts were not made by the Ottomans to pay them their arrears. This news combined with the importance of Nafpaktos to the Greeks, hastened their preparations to take the city. Byron’s arrival only furthered their plans much to his own dismay.

The reasoning behind Byron’s appointment was soon made abundantly clear, he was to lead a truly diverse force of klephts and Souliotes, Philhellenes, and common men, gathered from all across Greece. Under normal circumstances Markos Botsaris would lead the expedition himself to keep the men in check, however, his injuries from the year before continued to plague him, leaving Botsaris bedridden for a time. As such it was believed that Byron as a well-respected foreigner would be the most capable of managing the heated rivalries and intricate feuds between the diverse assembly of men who had gathered for this endeavor. His inexperience in military matters wasn’t so much an issue as he would be more of an overt figurehead for the operation, rather than a real soldier fighting in the trenches.

500 Souliotes were to form the core of Byron’s force, with his Italian companion Pietro Gamba being given the task of leading them. However, they immediately began causing trouble for Byron. They demanded payment in advance of their past and future services, they wanted security and safe passage to the Morea for their families, and they generally frustrated his efforts to turn them into a disciplined fighting force. When Markos Botsaris learned of the shameful behavior of his kinsmen, he rose from his sickbed and rode from his residence to Missolonghi and personally chastised the men responsible for giving their people a bad name. After this incident, the Souliotes generally shaped up and quieted down, even if they were still a completely rowdy and undisciplined bunch.[4]

Byron had also been granted 250 men by Demetrios Ypsilantis and the Greek Government, sent to aid the campaign and Mavrokordatos allowed Bryon permission to draw upon 1,200 men from the Missolonghi garrison as well. The final members of his force were the Philhellenes of the “Byron’s Brigade”, an informal military unit of 150 philhellenes paid for by Lord Byron himself that had assembled in Missolonghi in the weeks preceding and following his landing in Greece. Efforts were made by Byron and the Philhellenes to secure the arrival of a corps of artillery under the command of his friend and fellow Philhellene Thomas Gordon. However, delays and a change in command from Gordon to his subordinate William Parry caused some concern.[5] Convinced that these guns would be of no use of use against Nafpaktos’ walls, Botsaris pleaded with Byron to delay no longer and move against the city with all haste. Having come to trust the Souliot’s judgement, Byron reluctantly agreed to the proposal and departed Missolonghi for Nafpaktos on the 20th of January.

Nafpaktos and Nafpaktos Castle

Arriving outside Nafpaktos on the 22nd of January, Byron immediately opened negotiations with the defenders of the city as he had been instructed to do. As he was a foreigner, it was believed that Byron would the best candidate to gain the garrison’s surrender and see to their safety. This plan was thrown into disorder by the presence of the local Pashalik, Yusuf Pasha. The Ottoman had originally called the Albanian officers at Nafpaktos to Patras where they would ‘receive their long overdue reward’, but the movement of the Greeks against Nafpaktos and the perfidious nature of the Albanians prevented them from making the journey. Instead, Yusuf Pasha was himself, forced to travel north to meet with them at Nafpaktos arriving only moments after Byron and the Greeks.

Racing to cut off any talk of surrender, Yusuf Pasha immediately rejected Lord Byron’s terms, insisting upon the ability of his men to withstand a siege until reinforcements could arrive later in the spring. His decision made, the Turk turned his back on Byron and promptly locked himself away in the fortress overlooking the town. The Albanian captains, however, were more receptive to Byron’s offers of coin and a safe route home, and remained behind for several moments before returning to their walls as well. With nothing else to do but wait, Byron and the Greeks established a camp outside the walls of Nafpaktos while they awaited their response. Their answer came only a few moments later that night.

As night began to fall, shouting and screams, quickly followed by gunshots began filling the air, disrupting the calm winter night. Soon after, smoke began rising from Nafpaktos castle, and then flames. The Greeks, dumbfounded by the sight before them, initially did not know how to respond as they looked on in stunned disbelief. Their decision was soon made for them when the gates to the fortress were suddenly flung open in all the commotion.

In was be the one of the most bizarre episodes of the war, many of the Albanians inside the castle had turned against their Ottoman allies and began firing upon them. The Souliotes taking advantage of the situation, bravely rushed through the gates of the castle hacking their way through all who opposed them. They were soon followed by the rest of the Greeks who charged in as well. Together the Greeks and Albanians subdued the few Ottomans who had made the trip to Nafpaktos with Yusuf Pasha, and within mere moments, the castle had fallen.

Recognizing the impending defeat, Yusuf Pasha abandoned the castle with members of his guard and fled to awaiting transports in the town’s harbor that would return him to Patras. Under a constant rain of fire from the rampaging Albanians, the Ottomans barely escaped Nafpaktos with their lives, but in the process left behind several chests of Ottoman Piastres intended for the malcontent garrison. The Albanians for their part were spared, and per the terms of their surrender they were provided with enough coin to fulfill their needs before being allowed to leave in peace; the remaining Ottomans were not so lucky. Byron for his part managed to save their lives, but that was all he managed to achieve. They were quickly “liberated” of their weapons and their riches and held in the prison cells of the city before being shipped off aboard a neutral ship headed to Asia Minor.

In the following days, it would later be confirmed that the Ottoman Commander, Yusuf Pasha had discovered the correspondence between the Albanian Officers and the Greeks outside his walls. In his haste to punish the traitorous officers, he promptly executed the bunch without so much as a mock trial as if to display his authority and his justice. The move backfired spectacularly as the sudden arrival of the Greeks outside their walls, the continued lack of pay, and the seemingly unprovoked murder of their leaders prompted the remaining Albanians to turn against the Ottomans. Before Yusuf Pasha could allay their outrage with the riches and rewards he brought with him, the gates had been opened and the Greeks began flooding into the castle, forcing his retreat.

With Nafpaktos secured, the entire northern shore of the Gulf of Corinth, except for the village of Antirrio and the castle of Roumeli, were now in Greek hands. Finding the drier environment more to his liking than the mosquito infested lagoons near Missolonghi, Byron settled into a small manor overlooking the town. Despite liberating Nafpaktos, no serious effort was made to take the remaining Ottoman positions in the area due to a myriad of reasons ranging from politics to changing circumstances and by the middle of summer the plan was well and truly dead. Byron’s glorious military campaign in Greece had come to an end, less than a month after it began.

Next Time: The Baron and the Beggars

[1] Byron’s OTL journey to Missolonghi was much more adventurous in OTL. After leaving Cephalonia, the two ships became separated due to the slower speed of the bombard. The mistico that Byron was on was indeed confronted by an Ottoman ship during their first night at sea, but the Ottomans suspecting the boat to be a fireship left it alone. Unfortunately, they were forced to land further inland near Cape Skrophes due to more Ottoman ships in the area. The bombard that Byron’s companion Pietro Gamba had taken had its own adventure encountering a different Ottoman ship near Missolonghi. By chance the two captains knew each other as the Greek had saved the Turkish captain from a shipwreck in the Black Sea several years before the war. Unfortunately, Gamba’s ship was taken to Patras but the Turkish captain vouched for the honesty of the Greek captain and they were released. I owe Byron’s quieter crossing to the lack of a civil war taking place among the Greeks right now so more of their meager resources can be directed towards patrolling the seas near Missolonghi.

[2] Byron was essentially a millionaire by today’s standards, with a reputation for philanthropy. At one point in OTL he had a sum amounting to 20,000 Pounds Sterling which he fully intended to use on the Greek cause. With inflation, that amount is roughly equivalent to 1.5 million Pounds, which while not enormous by a government’s perspective, it certainly made him an incredibly valued commodity in the deeply impoverished state of Greece.

[3] While this is probably true in theory, it is really nonsense on Mavrokordatos’ part as it relies upon everything going according to plan and wouldn’t you know it nothing went to plan in OTL and a lot of things won’t go according to plan here either. Even if the Greeks had captured Nafpaktos as intended in OTL they would never have been able to force the Ottomans out of the Gulf in the manner they envisioned. The Sublime Porte recognized the importance in holding Patras and the castles at Rio and Antirrio and would certainly have committed the resources to holding them if they believed they were seriously threatened which they weren’t in OTL. Barring complete naval dominance, which the Greeks no longer possessed post 1822, they couldn’t feasibly take any of these sights without subterfuge.

[4] The Souliotes were an absolute menace during Byron’s time in Missolonghi. They constantly demanded back pay, bribes, and the transportation of their families to the Morea in return for their service. They were generally disruptive, constantly getting into fights and even killing an Italian Philhellene when he wouldn’t let him see their cannons. It got so bad that Byron was forced to pay them to leave Missolonghi and not return. Botsaris, being the respected figure that he is, could maintain a better degree of order and discipline that the OTL Souliotes lacked.

[5] While Byron and Parry quickly became fast friends and drinking partners, the shipment of artillery turned into a total fiasco in OTL. Parry had inexplicably forgotten to bring any coal with him which made the furnaces and artillery workshop he brought with him unusable. While they waited for coal to be brought to Missolonghi for the workshop, Yusuf Pasha discovered the plot at Nafpaktos and had the offending Albanians executed and the remainder paid ending the hopes of taking the castle by subterfuge. Additionally, a Souliot killed a member of Parry’s party, the Swedish Philhellene Adolph von Sass, when Sass refused to allow the Souliot near the cannons. When the Souliot was arrested his compatriots threatened to burn the city to the ground if their kinsman wasn’t released immediately. The killer was released, but the damage was done as many of Sass’s colleagues abandoned Greece altogether. Even if the cannons had been ready and able in February 1824, they would have had little to no effect on the thick walls of Nafpaktos’ castle, a point emphasized by the Souliotes repeatedly. Botsaris being the man that he was would strongly advocate for a lighting raid against Nafpaktos while it was still prone to treachery and knowing Byron I believe he would have sided with Botsaris on this point.

Lord George Gordon Byron, 6th Baron Byron, British Poet, and Philhellene

In many ways, 1823 ended the way it began, with the Ottomans withdrawing into Winter quarters after a failed assault on Missolonghi. In the East, the Ottomans had done little beyond the regular border raid into Boeotia, and at sea, the Ottoman fleet had been sent out under its third Kapudan Pasha in the past year, Khosref Pasha. Khosref Pasha, despite being a decadent old man more suited for the pleasures of retirement than the rigors of war, still managed to take the lessons of the last year to heart, trading the heavy Ships of the Line for more agile frigates, corvettes, and brigs widely used by the Greeks. Traveling to Evvia (Euboea), Khosref reinforced the Ottoman garrison of Karistos before making a supply run around the Morea. On his return to Constantinople in October his fleet was ambushed by the Greeks off the coast of Tenedos resulting in the capture of two corvettes and four brigs. While certainly embarrassing, this battle was not the worst mishap for the Ottoman Navy that year. No, that distinct dishonor fell to a particular naval engagement off the coast of Missolonghi that did not take place.

On the 29th of December, two ships flying the flag of the Ionian Islands departed from the port of Metaxa on the island of Cephalonia. The ships, a bombard and a mistico, were traveling for the city of Missolonghi carrying a cache of rifles, several horses, a few hunting dogs, and 25 passengers, with the most prominent being a British Peer intent on joining the fight in Greece. Immediately their crossing was beset by problems, the bombard being larger was quickly outpaced by the sleeker mistico, and by nightfall they had become completely seperated. There most trying episode came on the first night as the mistico soon ran afoul of a patrolling Ottoman Corvette. Panic gripped the passengers and crew as they quickly moved to destroy any incriminating evidence that might contradict their cover story that they were simply headed towards Kalamos for a hunting expedition. The lanterns were doused, the dogs were muzzled and the passengers hid themselves. When no response came from the boat, the Ottoman vessel began to pull alongside. Were it not for the sudden emergence of three Greek ships from the darkness causing the Ottoman vessel to flee, the ship would have likely been detained at Patras for days at the very least if not indefinitely. With the Ottoman ship in retreat, the Greeks moved alongside the small mistico, offering the ship safe passage to Missolonghi. Arriving on the 1st of January in the early morning, Lord Byron stepped ashore in Greece.[1]

Lord Byron, was one of thousands of Philhellenes from across Europe and the Americas who made their way to the Balkans to aid the Greeks over the course of the war. Many were soldier like Sir Richard Church, Charles Nicolas Fabvier, and Karl von Norman-Ehrenels who joined the Greeks as commanders on the field of battle. Others were diplomats like Viscount Stratford Canning and his cousin, the statesman George Canning who aided the Greeks from abroad with their diplomacy and politicking. Then there were artists like the painters Louis Dupre and Peter von Hess whose works of art galvanized the masses. Many chose to form groups with the express purpose of raising funds for the Greek state, the largest and most influential being the London Greek Committee of which Lord Byron was a prominent member.

George Gordon Byron was the son of Captain John “Mad Jack” Byron of the Coldstream Guard and his wife, Lady Catherine Gordon of Gight. George, more commonly known as Lord Byron was the 6th Baron Byron of his family, a family with a long pedigree of accomplished scholars, soldiers, sailors, and poets. Despite being born into nobility, his childhood was hardly whimsical or luxurious. His father was an infamous debtor, one who squandered his wife’s fortune meeting his lavish expenses. Captain Byron was for all intents and purposes a bastard and a vagabond, who violently beat his first wife to the brink of death on many occasions and married his second wife, Catherine, solely for her extensive wealth. His excessive gambling drove Byron’s mother to depression and heavy bouts of drinking over her husband’s treatment of her and their son. It is fortunate for all involved that “Mad Jack” died in 1791 while overseas in Valenciennes, France.

Captain Jack Byron (Left) and Lady Catherine Gordon of Gight (Right)

Lord Byron’s troubles did not end there, however. He would prove himself to be quite unskilled as a scholar in his early years and he lacked the physical prowess of a military man due to a sickly constitution and a clubbed right foot. Due to his condition, he was regularly wracked with depression and prone to fits of anger. His only remarkable qualities seem to have been found in his mastery of the arts, specifically poetry. Byron had a way with words that made young maidens swoon, and grown men cry. His poetry tended to be the topic of conversation from the proper folk of British high society to the common man on the streets. To be referenced within any of his works was often considered a badge of honor whether it be for good or for ill.

Many of Byron’s poems were thinly veiled soliloquys of his own illustrious love life. Throughout his years, Lord Byron would have no less than six lovers and according to rumors he engaged in many more unrecorded affairs, with the most scandalous allegedly being an affair between Byron and his half-sister Augusta Leigh. His married life was not so successful, with two attempts ending in divorce. Byron has also had at least five confirmed children, both legitimate and out of wedlock. Byron was an eccentric fellow who on occasion dabbled in homosexual activities with his companions. Despite his many affairs, and numerous scandals in the name of romance, by far the greatest love of his life, however, were the lands of Italy and Greece. Like many he found these ancient lands to be intoxicating and romantic, filled with ideas of art, liberalism, philosophy, and romance. It was during his time on tour in Genoa, that war broke out in Greece and while he lacked in military experience or feats of strength he nevertheless found the conflict to be an exciting chance at adventure, carried out in pursuit of a noble cause. With all the gusto and extravagance of a nobleman and a poet, Byron left Italy to aid the Greeks in their effort.

Traveling first to the Ionian Island of Cephalonia where he would stay for nearly four months, Byron soon became inundated with letters from the many chief actors across Greece. Petros Mavromichalis invited him to Nafplion, Georgios Kountarious to Hydra, Odysseus Androutsos to Athens, and Alexandros Mavrokordatos to Missolonghi. Each called on Byron to join them and lend them his aid; though in truth each were thinly veiled ploys to gain access to his money and resources for their own personal ventures.[2] Despite the tenacity and vigor of these competitors it was his correspondence with the Souliot Markos Botsaris which finally drew Byron to Missolonghi, where he arrived on the 1st of January 1824. Barely halfway off the boat, Byron was immediately put to work. At the personal behest of Alexandros Mavrokordatos and Markos Botsaris, Byron was appointed to work on their latest endeavor, an assault on the strategically important town of Nafpaktos.

Byron arrives in Missolonghi

Nafpaktos, or Lepanto as the Venetians once called it, was founded along the northern littoral of the Gulf of Corinth 25 miles to the east of Missolonghi. Nafpaktos was a small town, with no more than 6,000 people most of whom fled at the onset of the war. Surrounded by impressive ramparts of Venetian design, Nafpaktos possessed one of finest natural harbors in all of Greece and its situation near the Gulf of Corinth made it a perfect refuge for Ottoman ships in the region. But it was Nafpaktos castle which was truly impressive, with its stout walls and imposing citadel it was a foreboding sight overlooking the harbor from its hill and as one of the largest fortifications in all of Greece, it made for an enticing target.

With Nafpaktos under their control, the Greeks believed they would roll up the remaining Ottoman possessions in the Gulf. 6 Miles to the West was the Castle of the Roumeli in Antirrio, and directly across the water was its counterpart, the Castle of the Morea and the small fishing hovel of Rio. To the West of Rio was the city of Patras and its mighty castle, making them the greatest remaining Ottoman possessions in the Morea. With Nafpaktos liberated, the castles of the Roumeli and the Morea, along with the city and citadel of Patras would be rendered indefensible forcing the Ottomans to abandon their remaining holdings on the Gulf, or risk the loss of several thousand soldiers and civilians.[3]

The outcome of the expedition was predicated upon the authenticity of recent reports which provided the Greeks with a decided advantage, but also a strict deadline. Word had emerged from within Nafpaktos that the Albanian garrison was on the verge of revolt. Having gone without proper pay for 18 months, and forced to man the castle well beyond their contracted terms of service, unrest had become understandably high among the Albanian mercenaries, and while it was not spoken aloud, in private they allegedly made threats announcing they would surrender the fortress to the Greeks if efforts were not made by the Ottomans to pay them their arrears. This news combined with the importance of Nafpaktos to the Greeks, hastened their preparations to take the city. Byron’s arrival only furthered their plans much to his own dismay.

The reasoning behind Byron’s appointment was soon made abundantly clear, he was to lead a truly diverse force of klephts and Souliotes, Philhellenes, and common men, gathered from all across Greece. Under normal circumstances Markos Botsaris would lead the expedition himself to keep the men in check, however, his injuries from the year before continued to plague him, leaving Botsaris bedridden for a time. As such it was believed that Byron as a well-respected foreigner would be the most capable of managing the heated rivalries and intricate feuds between the diverse assembly of men who had gathered for this endeavor. His inexperience in military matters wasn’t so much an issue as he would be more of an overt figurehead for the operation, rather than a real soldier fighting in the trenches.

500 Souliotes were to form the core of Byron’s force, with his Italian companion Pietro Gamba being given the task of leading them. However, they immediately began causing trouble for Byron. They demanded payment in advance of their past and future services, they wanted security and safe passage to the Morea for their families, and they generally frustrated his efforts to turn them into a disciplined fighting force. When Markos Botsaris learned of the shameful behavior of his kinsmen, he rose from his sickbed and rode from his residence to Missolonghi and personally chastised the men responsible for giving their people a bad name. After this incident, the Souliotes generally shaped up and quieted down, even if they were still a completely rowdy and undisciplined bunch.[4]

Byron had also been granted 250 men by Demetrios Ypsilantis and the Greek Government, sent to aid the campaign and Mavrokordatos allowed Bryon permission to draw upon 1,200 men from the Missolonghi garrison as well. The final members of his force were the Philhellenes of the “Byron’s Brigade”, an informal military unit of 150 philhellenes paid for by Lord Byron himself that had assembled in Missolonghi in the weeks preceding and following his landing in Greece. Efforts were made by Byron and the Philhellenes to secure the arrival of a corps of artillery under the command of his friend and fellow Philhellene Thomas Gordon. However, delays and a change in command from Gordon to his subordinate William Parry caused some concern.[5] Convinced that these guns would be of no use of use against Nafpaktos’ walls, Botsaris pleaded with Byron to delay no longer and move against the city with all haste. Having come to trust the Souliot’s judgement, Byron reluctantly agreed to the proposal and departed Missolonghi for Nafpaktos on the 20th of January.

Nafpaktos and Nafpaktos Castle

Arriving outside Nafpaktos on the 22nd of January, Byron immediately opened negotiations with the defenders of the city as he had been instructed to do. As he was a foreigner, it was believed that Byron would the best candidate to gain the garrison’s surrender and see to their safety. This plan was thrown into disorder by the presence of the local Pashalik, Yusuf Pasha. The Ottoman had originally called the Albanian officers at Nafpaktos to Patras where they would ‘receive their long overdue reward’, but the movement of the Greeks against Nafpaktos and the perfidious nature of the Albanians prevented them from making the journey. Instead, Yusuf Pasha was himself, forced to travel north to meet with them at Nafpaktos arriving only moments after Byron and the Greeks.

Racing to cut off any talk of surrender, Yusuf Pasha immediately rejected Lord Byron’s terms, insisting upon the ability of his men to withstand a siege until reinforcements could arrive later in the spring. His decision made, the Turk turned his back on Byron and promptly locked himself away in the fortress overlooking the town. The Albanian captains, however, were more receptive to Byron’s offers of coin and a safe route home, and remained behind for several moments before returning to their walls as well. With nothing else to do but wait, Byron and the Greeks established a camp outside the walls of Nafpaktos while they awaited their response. Their answer came only a few moments later that night.

As night began to fall, shouting and screams, quickly followed by gunshots began filling the air, disrupting the calm winter night. Soon after, smoke began rising from Nafpaktos castle, and then flames. The Greeks, dumbfounded by the sight before them, initially did not know how to respond as they looked on in stunned disbelief. Their decision was soon made for them when the gates to the fortress were suddenly flung open in all the commotion.

In was be the one of the most bizarre episodes of the war, many of the Albanians inside the castle had turned against their Ottoman allies and began firing upon them. The Souliotes taking advantage of the situation, bravely rushed through the gates of the castle hacking their way through all who opposed them. They were soon followed by the rest of the Greeks who charged in as well. Together the Greeks and Albanians subdued the few Ottomans who had made the trip to Nafpaktos with Yusuf Pasha, and within mere moments, the castle had fallen.

Recognizing the impending defeat, Yusuf Pasha abandoned the castle with members of his guard and fled to awaiting transports in the town’s harbor that would return him to Patras. Under a constant rain of fire from the rampaging Albanians, the Ottomans barely escaped Nafpaktos with their lives, but in the process left behind several chests of Ottoman Piastres intended for the malcontent garrison. The Albanians for their part were spared, and per the terms of their surrender they were provided with enough coin to fulfill their needs before being allowed to leave in peace; the remaining Ottomans were not so lucky. Byron for his part managed to save their lives, but that was all he managed to achieve. They were quickly “liberated” of their weapons and their riches and held in the prison cells of the city before being shipped off aboard a neutral ship headed to Asia Minor.

In the following days, it would later be confirmed that the Ottoman Commander, Yusuf Pasha had discovered the correspondence between the Albanian Officers and the Greeks outside his walls. In his haste to punish the traitorous officers, he promptly executed the bunch without so much as a mock trial as if to display his authority and his justice. The move backfired spectacularly as the sudden arrival of the Greeks outside their walls, the continued lack of pay, and the seemingly unprovoked murder of their leaders prompted the remaining Albanians to turn against the Ottomans. Before Yusuf Pasha could allay their outrage with the riches and rewards he brought with him, the gates had been opened and the Greeks began flooding into the castle, forcing his retreat.

With Nafpaktos secured, the entire northern shore of the Gulf of Corinth, except for the village of Antirrio and the castle of Roumeli, were now in Greek hands. Finding the drier environment more to his liking than the mosquito infested lagoons near Missolonghi, Byron settled into a small manor overlooking the town. Despite liberating Nafpaktos, no serious effort was made to take the remaining Ottoman positions in the area due to a myriad of reasons ranging from politics to changing circumstances and by the middle of summer the plan was well and truly dead. Byron’s glorious military campaign in Greece had come to an end, less than a month after it began.

Next Time: The Baron and the Beggars

[1] Byron’s OTL journey to Missolonghi was much more adventurous in OTL. After leaving Cephalonia, the two ships became separated due to the slower speed of the bombard. The mistico that Byron was on was indeed confronted by an Ottoman ship during their first night at sea, but the Ottomans suspecting the boat to be a fireship left it alone. Unfortunately, they were forced to land further inland near Cape Skrophes due to more Ottoman ships in the area. The bombard that Byron’s companion Pietro Gamba had taken had its own adventure encountering a different Ottoman ship near Missolonghi. By chance the two captains knew each other as the Greek had saved the Turkish captain from a shipwreck in the Black Sea several years before the war. Unfortunately, Gamba’s ship was taken to Patras but the Turkish captain vouched for the honesty of the Greek captain and they were released. I owe Byron’s quieter crossing to the lack of a civil war taking place among the Greeks right now so more of their meager resources can be directed towards patrolling the seas near Missolonghi.

[2] Byron was essentially a millionaire by today’s standards, with a reputation for philanthropy. At one point in OTL he had a sum amounting to 20,000 Pounds Sterling which he fully intended to use on the Greek cause. With inflation, that amount is roughly equivalent to 1.5 million Pounds, which while not enormous by a government’s perspective, it certainly made him an incredibly valued commodity in the deeply impoverished state of Greece.

[3] While this is probably true in theory, it is really nonsense on Mavrokordatos’ part as it relies upon everything going according to plan and wouldn’t you know it nothing went to plan in OTL and a lot of things won’t go according to plan here either. Even if the Greeks had captured Nafpaktos as intended in OTL they would never have been able to force the Ottomans out of the Gulf in the manner they envisioned. The Sublime Porte recognized the importance in holding Patras and the castles at Rio and Antirrio and would certainly have committed the resources to holding them if they believed they were seriously threatened which they weren’t in OTL. Barring complete naval dominance, which the Greeks no longer possessed post 1822, they couldn’t feasibly take any of these sights without subterfuge.

[4] The Souliotes were an absolute menace during Byron’s time in Missolonghi. They constantly demanded back pay, bribes, and the transportation of their families to the Morea in return for their service. They were generally disruptive, constantly getting into fights and even killing an Italian Philhellene when he wouldn’t let him see their cannons. It got so bad that Byron was forced to pay them to leave Missolonghi and not return. Botsaris, being the respected figure that he is, could maintain a better degree of order and discipline that the OTL Souliotes lacked.

[5] While Byron and Parry quickly became fast friends and drinking partners, the shipment of artillery turned into a total fiasco in OTL. Parry had inexplicably forgotten to bring any coal with him which made the furnaces and artillery workshop he brought with him unusable. While they waited for coal to be brought to Missolonghi for the workshop, Yusuf Pasha discovered the plot at Nafpaktos and had the offending Albanians executed and the remainder paid ending the hopes of taking the castle by subterfuge. Additionally, a Souliot killed a member of Parry’s party, the Swedish Philhellene Adolph von Sass, when Sass refused to allow the Souliot near the cannons. When the Souliot was arrested his compatriots threatened to burn the city to the ground if their kinsman wasn’t released immediately. The killer was released, but the damage was done as many of Sass’s colleagues abandoned Greece altogether. Even if the cannons had been ready and able in February 1824, they would have had little to no effect on the thick walls of Nafpaktos’ castle, a point emphasized by the Souliotes repeatedly. Botsaris being the man that he was would strongly advocate for a lighting raid against Nafpaktos while it was still prone to treachery and knowing Byron I believe he would have sided with Botsaris on this point.

Last edited:

Speaking of Byron?

Sorry my computer temporarily froze on me, I swear!Did you accidentally delete the rest of the post

King Byron of Greece, now that would be something. Don't worry I have plans for Byron in the future.King Gordon I of Greece?

Okay, SUPER unlikely - but whoa would that make for an interesting development

I haven't worked out the specifics, but it probably won't be much bigger than the 1832 borders initially. That being said that doesn't mean their won't be other territorial changes that work to the benefit of Greece.How much larger can Greece be without the in-fighting and squandering of loans that happened OTL?

Unfortunately some people in power across Europe, specifically Metternich in Austria and Wellington in Britain both opposed a Greater Greece, both even wanted it to remain apart of the Ottoman Empire even as late as 1826/1827, and even in TTL they will still carry some weight in the eventual Peace Conference.

Good update. Like that you're mentioning Lord Byron. BTW, one of my cats was named Lord Byron; his back legs were deformed (surprisingly, his mother didn't kill him when he was born, as happens with a lot of disabled kittens), so he basically had to scuttle to walk (he had strong upper body strength). He survived for about a couple of years, BTW. My mom named him Byron because he had deformed back legs and Byron had had club feet (plus, she was a fan of his poems)...

Hope Lord Byron survives longer here...

Hope Lord Byron survives longer here...

I think that without botching up most of the war the Greeks can get Thesally and Dodecanes islands without much trouble if they form a less radical government.I haven't worked out the specifics, but it probably won't be much bigger than the 1832 borders initially. That being said that doesn't mean their won't be other territorial changes that work to the benefit of Greece.

Unfortunately some people in power across Europe, specifically Metternich in Austria and Wellington in Britain both opposed a Greater Greece, both even wanted it to remain apart of the Ottoman Empire even as late as 1826/1827, and even in TTL they will still carry some weight in the eventual Peace Conference.

Last edited:

The problem the Greeks faced in OTL, was that once the Great Powers became involved in Greece, they essentially handled all of the negotiations with the Ottoman Empire purely to maintain their interests and unfortunately those interests didn't include a larger Greece. While some delegates were in favor of a stronger Greece they were generally in the minority, even the Ottomans had a larger say in the peace negotiations than the Greeks did, at least in the 1830 London Conference.I think that without botching up most of the war the Greeks can get Thesally without much trouble

That being said the exact nature of the border was strongly influenced by the situation on the ground in 1829 when the armistice went into effect. By the time of the London Conference in 1830, the Greeks had finally reclaimed the Morea with the help of the French Expedition, beginning in 1828, Sir Richard Church had retaken the Gulf of Arta and the Makrinoros Mountains in the West during the Spring of 1829, and Demetrios Ypsilantis had liberated Thebes, Salona, and Livadhia in the East by the Fall of 1829. Nothing is set stone as of now so if in the process of writing this the Greeks get on a good run then Thessaly could definitely be in the cards, just don't expect them to take Constantinople or Asia Minor...yet.

Chapter 12: The Baron and the Beggars

Chapter 12: The Baron and the Beggars

Byron at Salona

In the months that followed his arrival in Greece, Lord Byron became increasingly distressed by the growing factiousness of the Greeks. Though the war against the Turk had done much to suppress the old rivalries and tensions between the various clans and communities in Greece, by the Spring and Summer months of 1824 their united front had begun to ware off, much to Byron’s dismay. Unable to bridge the divide between the Greeks, Byron busied himself by riding through the countryside alongside his faithful, albeit entirely incompetent companion Pietro Gamba. His most frequent destination was Missolonghi where he had developed a budding friendship with Alexandros Mavrokordatos due to their shared interest in the arts and philosophy.

Mavrokordatos had been recalled to the area following a raid on Aitoliko by the Turks in late December 1823 and his arrival in Missolonghi proved to be a strong factor in Byron’s decision to land in Western Greece as opposed to the Morea. Lord Byron thought so highly of Mavrokordatos that he considered him to be the Greek George Washington. Their conversations often drifted from politics and the war to more pleasant topics like art, drama, poetry, and philosophy. While, he had come to respect Mavrokordatos as a friend, it was the Souliot Markos Botsaris who truly won Byron over by sheer strength of personality. Botsaris was a larger than life figure. Renowned for his integrity, a trait uncommon amongst the other Greek captains of the war, and his unflinching dedication to the cause was unmatched, Markos Botsaris was a truly noble and heroic figure amongst the Greeks. He was charming, bold, strong, and incredibly savvy, and while the legends swirling about him certainly overshadowed the real man, Lord Byron found the Souliot’s honesty refreshing. It had been their correspondence that led Byron to Greece in the first place.[1]

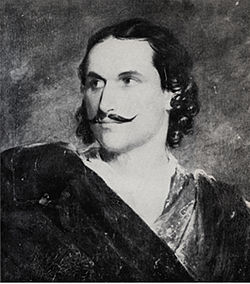

Despite his decision to land in Missolonghi and his desire to work alongside Mavrokordatos and Botsaris, other magnates across Greece continued their attempts to pry the Briton to their sides, with the most persistent being Odysseus Androutsos. Androutsos had been one of the chief architects of the liberation of Athens in 1822 and as a result of his success he had become a powerful actor in Central Greece. Androutsos was a talented leader, a skilled fighter, and a brilliant orator, yet his greatest flaw was his overly grand ambition. Coming to view Athens as his own personal fief, Androutsos began efforts to cement his rule over the city, an endeavor that brought him into conflict with the National Government in Nafplion. Despite his own talent and the support of the local Athenians, Androutsos recognized the necessity of strong allies if he were to effectively challenge the Greek Government. Having already seduced Byron’s longtime friend and fellow adventurer, Edward John Trelawny, and their colleague Colonel Leicester Stanhope to his side, Androutsos, believed he could similarly win over Byron and in doing so, lay claim to Byron’s vast resources.

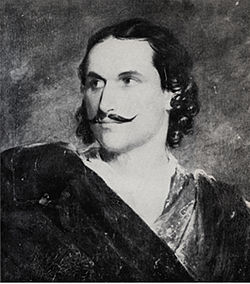

Odysseus Androutsos (Left) and Edward Trelawny (Right)

The real boon that Lord Byron provided to the Greek cause wasn’t his military skill or his acumen with words, but rather, it was his enormous personal wealth and his personal philanthropy that made him an attractive sponsor of the Greeks. The Greek countryside under the Ottomans had been deprived of wealth for generations while the islands and cities flourished. The farmers and peasants of Greece became destitute and deeply impoverished leading many to seek a life as a klepht to provide for their families. In Ottoman Greece, it cost less to house a family for an entire year than it would to feed them for a month. Labor and housing were cheap but resources and commodities were not. With over half of the arable land in Greece under the control of the church, state, and local magnates, many people within Ottoman Greece were left to starve, or subsist upon a pittance of poor land. Those Greeks who found themselves in Constantinople or on one of the many islands tended to do better than their Morean and Rumelian countrymen, building lavish houses of stone and marble, but even their wealth paled in comparison to the opulence and grandeur of those in the West. The Greek merchants of Chios, Hydra, Psara, Samos, and Spetses had themselves only come into their wealth recently, smuggling large quantities of grain to Napoleonic France from Egypt.

The economic situation in Greece was made worse by the rampant inflation in the Ottoman Empire over the course of the 19th Century thus far. In 1815, the value of the Ottoman Piastres, the currency used throughout the Empire, had a value of 20 to 1 against the British Pound Sterling. By the time of Byron’s arrival in Greece in 1824, the Piastre had fallen as low as 50 to 1 against the Pound, a loss of over 50% of its value in less than 9 years. The war had done much to accelerate this process as the Porte, desperately short on available manpower in the first two years of the conflict, resorted to minting more coins to pay the exorbitant costs of Arab and Albanian mercenaries. As the war progressed, foreign currencies became more prominent across Free Greece to make up the difference of the devaluing Piastre, with the Pound being the most popular, but also the rarest.

The Greek’s themselves had little means of raising the funds necessary to finance a war beyond looting, as the collection of tariffs and taxes was nigh impossible in the war-torn country. What plunder the Greeks could gather from their victories was often divided amongst the soldiers and their leaders as recompense for their services, as the government often lacked the funds to pay them, with only a small faction being sent to the state.[2] The only real source of dependable income the Greek Government could rely upon were the donations, grants, and loans sent from their supporters abroad. Even these would not be enough as the Greek Government had spent a sum in excess of £600,000 in 1823 alone, much of which was spent paying the excessive prices needed to keep the Greek navy as Sea.

Lord Byron was one of these private donors as he spent lavish sums of coin on the arming and training of Greek partisans amounting to a small fortune. His first act in the war was to “loan” £4,000 to the Greek Government for the commissioning of 5 ships from Hydra and Spetses that would patrol the waters near Missolonghi over the Winter and Spring months of 1824, the very same ships that had aided in his arrival in Greece. Within weeks of his arrival in Missolonghi, Byron would give an additional £2,000 to the Souliotes in Cephalonia and another £2,000 in Missolonghi, although this amount was reduced to £1,500 thanks to the efforts of Markos Botsaris. Another £1200 were spent by Byron to fund the deployment of the Government troops to Missolonghi and the organization of the ‘Byron Brigade, a force of fellow Philhellenes and Diaspora Greeks amounting to roughly 300 men at its height in December 1824. Byron also made a pair of loans, to the sum of £1,500 first to Mavrokordatos and then to William Parry upon his arrival in Greece in early February. He even went so far as to sell his own home in Scotland, Rochdale Manor, raising a further £11,000 which he had every intention of spending on the Greek cause.

Byron had another, more important role in Greece aside from volunteer and philanthropist, and that was of a custodian and arbitrator of the London Greek Committee’s loan to Greece in 1824. On the 22nd of February 1823 Andreas Louriotis arrived in London to begin efforts to contract a loan with the city. London was the economic capital of the world in the early 19th century and as such it was the only place where the Greeks could amass the amount of funds they so desperately needed. Through the aid of the Philhellene Edward Blaquiere, Louriotis was introduced to a group of two dozen prominent businessmen, politicians and nobles, including Byron’s closes friend John Cam Hobhouse and Thomas Gordon. These men would in the following days form the London Greek Committee, an organization bent on aiding the independence of Greece from the Ottoman Empire. To that end, the Committee tasked Blaquiere with traveling to Greece where he would report on the state of the war in Greece and receive the permission of the Greek Government to begin contracting a loan with one of their agents. Returning to London in September, Blaquiere gave an incredibly overestimated account of the economic state of Greece and their viability in the war. When the Greek agents Andreas Louriotis and Ioannis Orlandos arrived in London on the 21st of January 1824, they immediately set to work hammering out the fine details of the loan contract.

The Crown and Anchor Tavern (Right), “Headquarters” of the London Greek Committee

After nearly a month, they reached an agreement. Greek bonds would be raised for the nominal value of £800,000, at a price of £100 per bond, that would be paid back at a 5% interest rate by the Greek Government. However, trouble soon arose due to the chicanery of the Committee, as the bonds were sold at 59% of the agreed value, bringing the actual amount of money that would be loaned to Greece closer to £472,000. However, this amount was buoyed somewhat by news of Lord Byron’s successes in Greece, boosting the bonds up to 67%, or roughly £536,000.[3] This sum was then reduced further by the retention of two years’ interest by the London Greek Committee, the repayment of Lord Byron’s earlier loans, and the payment of commissions to the negotiators, giving the loan a final total of £420,000, with an actual interest rate of 7.5%.

One last caveat of the deal was that the loan would be dispensed at the discretion of two representatives from the London Greek Committee. This term was to ensure the funds were used towards an appropriate purpose, rather than being spent at the discretion of an unscrupulous klepht. Lord Byron and Colonel Leicester Stanhope, being the two most prominent members of the Committee in Greece at the time were chosen for this task. However, at the complaint of the Greek deputies, two representatives were also added for the Greeks to add parity to the British. Lazaros Kountarious and Andreas Londos were selected for the task owing to their influence and support within the Greek Government.[4] The optimistic reports from Stanhope and Byron helped the Committee reach the total sum of the loan and by the end of April 1824 the first installment arrived in Greece.

Access to the loan was Androutsos’ true motivation for courting Byron. Londos and Kountarious were too prideful to side with Androutsos and while Stanhope was already smitten with him, his tenure in Greece was scheduled to end in May as per his arrangement with the Royal Army, leaving Lord Byron as the only remaining custodian of the loan he could appeal towards. Stanhope believing Androutsos to be the worthiest recipient of the loan, pushed his benefactor to organize the Congress of Salona with his ally the Phanariot Theodoros Negris. The Congress was ostentatiously an attempt to resolve the many issues between the disparate groups within Greece, but in truth it was an opportunity for Androutsos to draw Byron to his side. Much to the annoyance of Mavrokordatos and Botsaris, Byron accepted the invitation when Stanhope and Trelawny personally endorsed the event as an initiative capable of promoting a united front for the Greeks. Knowing full well that Androutsos would attempt to poach Byron from them, Mavrokordatos departed for Salona as well under the guise of protecting the national interests of the Greek Government.

After many delays, mostly at the behest of Mavrokordatos, including a raid on Missolonghi by the Epirote Georgios Karaiskakis in early April, and several weeks of incredibly poor weather, the Congress of Salona officially opened on the 6th of May. To say that the Congress achieved anything of note would be incredibly kind to it. The event opened politely enough, with the exchange of pleasantries and the recital of the grievances which had spurned them all to rebellion against the Sublime Porte in the first place. Soon, however, it degenerated into a shouting match between rival parties. Byron ever the wordsmith, waded into the crowd to intervene in the heated debate, but was knocked to the ground in the process while making his way to stage. The stress of the situation, combined with an especially difficult journey for Byron proved detrimental to his health forcing him to be rushed from the Congress Chamber. Unfortunately for Byron, his “illness” kept him bedridden for the much of the event and due to the posturing of companion Mavrokordatos, Byron was cloistered away from any visitors.

By the time Byron recovered from his illness, many of the delegates had returned to their strongholds and Colonel Stanhope had departed for Britain. The only verifiable product of the Congress had been a relatively meaningless declaration of support for the revolution and the government in Nafplion by the events attendees.[5] Androutsos much to his dismay was denied his chance at winning Byron over with his legendary charisma when the Briton returned to Missolonghi with barely a word exchanged between them. Mavrokordatos had seen to it that the brigand would not receive another chance.

The entire escapade taught Byron, that he was not the man to bring the Greeks together, that man required the strength of will and the strength of body to drag the warring Greeks together. This point that was reaffirmed several weeks later when he traveled to the city of Nafplion in early July to meet with the Central Government. The conference between them was an awkward affair for Byron as he would later write it in his memoirs. It was a conversation filled with vague promises of support for the Roumeli and false shows of solidarity, outright lies and half-truths. Byron blamed their behavior on the looming crisis in Psara and the recent fall of Kasos. By the end of the meeting, Byron had to retire to the manor of the local bishop to recover from the stress of the ordeal. For Byron, a man plagued with relatively poor health for much his life, the adventure in Greece had taken its toll.

When the last installment of the loan arrived in early May 1825, Byron began preparing to return to Britain, a place he had not seen in years. While he would continue to support the Greeks in their bid for independence he had been thoroughly exhausted by their petty bickering and infighting, infighting had only gotten worse in the short time he had been there, though in no part due to a lack of effort on Byron’s part. The weather had also disappointed him as it rained more often than not, denying him the opportunities to explore the ruins of the ancient world and leaving him feverish on many occasions. Before leaving Greece to lobby for further aid, he bestowed the remainder of his available funds, a sum amounting to slightly over 3,000 Pounds, to his allies Botsaris and Mavrokordatos, two men he had come to trust as noble patriots, god fearing men, and good friends. With his business in Greece settled for now, Lord Byron left Greece on the 2nd of June, for home.[6]

Byron’s impact on the Greek War of independence is hard to discern. He failed in his efforts to unite the Greeks, and his military endeavors ended before they had a chance to begin. It was only in his financiering and philanthropy that Byron made a tangible effect while in Greece during the war. His stewardship of the London Greek Committee Loan proved to be adequate, if not effective. While he was by no means a man of a military background, he had listened to Stanhope’s suggestions closely while he was in Greece, and tried to the best of his ability to remain to those words after the Colonel’s departure. That being said, the use of the loan was generally left to the Greeks to decide, with much being spent towards it arrears and funding its naval expeditions.

If one had to decide upon the most lasting effect of Byron’s time in Greece it would have to be his extensive acts of charity. For a man with a strained relationship with his own children, Byron cared for orphaned boys and girls, both Christian and Muslim alike, as a doting father would their own child. At first, he lavished them with fine clothing and provided for them an excellent education, and for a brief moment, Byron even considered adopting a Turkish girl and a Greek boy as his own children. As time passed, Byron gradually expanded his efforts to aid all the children of Greece. Byron would be personally accredited with founding three separate orphanages across Free Greece during the war and sponsoring the construction of fifteen more in the years that followed, of these four were unfortunately destroyed in the fires of war, and only one remains to this day in any recognizable state. His erstwhile colleague Colonel Stanhope also aided Byron in the building of twelve schools across Greece both during and after the war.

Despite Byron’s best efforts to aid the Greeks, his work to bring them together only resulted in a brief pause in the inevitable march towards schism between the Greeks. There existed too much bad blood, too many bruised egos, and too much hatred, to simply be wiped away by the common cause of independence and the honest, but naïve efforts of Byron. By the end of 1824, civil war seemed imminent in Greece.

Next Time: The Greek Schism

[1] Byron had been in communication with Markos Botsaris. In fact, in OTL the last letter that Botsaris wrote was to Byron, imploring him to come to Greece in person to aid them in their cause. While their backgrounds were different I believe that Byron and Botsaris would have gotten along very well.

[2] This system of looting had been installed by Theodoros Kolokotronis in the opening months of the war. One third of the spoils were to go to the officers, one third would go to the soldiers, and the remaining third would go to the government, but due to corruption, negligence, and a general distrust of the government, they usually received far less than their established amount.

[3] To say that the 2 loans in OTL were a complete debacle is being too generous, they were scams. The first loan was offered at £800,000 but the death of Lord Byron caused the bonds to tank in price from 63% in February, to 43% by the end of April. After all the fees and commissions were taken out, Greece only received about £350,000. Despite this the Greek Government was still expected to pay interest on the original 800,000 despite only receiving a small fraction of it, resulting in an actual interest rate of 8.5% as opposed to the official 5% they agreed to. The second loan in 1825/1826 was just as egregious, this time being for 2 million pounds, with only 1.1 million reaching Greece. Most of the second loan was then wasted on 6 steamships that didn’t work and two American frigates which were outrageous over priced at £185,000 apiece, although they were very nice ships. Because of the terrible way in which these loans were handled, Greece was laden with debt that it struggled to pay off for years, only having it renegotiated to a lower amount rate near the end of the 19th century.

[4] Byron and Stanhope were selected in OTL, and owing to their nature and their lives up to the POD, I don’t believe anything would have changed their reasoning for traveling to Greece. As they were the highest profile Committee members in Greece at the time of the agreement, they were chosen to be its commissioners as in OTL. Lazaros Kountarious was chosen for his close relations to Ioannis Orlandos, his brother in law, and his brother Georgios Kountarious was a powerful member of the Greek Government. Selecting the 4th Commissioner was a bit tricky as I don’t believe it was filled in OTL so I don’t have a historical analogue to compare to. My reasoning for choosing Andreas Londos stems entirely from the fact that he is a neutral leaning Morean with a close friendship to Andreas Zaimis, who sits on the Executive. If anyone else would be a better candidate please let me know and I will consider changing it.

[5] The Congress of Salona, modern day Amphissa, was an entirely worthless venture in OTL. Androutsos had really intended to win Byron over at the event, but his untimely death prevented his plans from unfolding how he intended. Even if Byron had lived to attend the Congress, nothing significant would have likely come from it.

[6] Byron’s cause of death in OTL is unknown, but it is believed to have been a brain hemorrhage followed by several days of inadequate and downright dangerous medical practices. It is likely the hemorrhage was induced by the stress related stroke he suffered in February and then reaggravated it during his fever in early April. He accredited the first seizure to his heavy drinking with Parry, his lack of exercise due to the rain, and the stressful interactions he had with the Souliotes while in Missolonghi. I would argue that a Botsaris that survives Karpenisi would significantly aid Byron during his time in Missolonghi preventing some of the conditions that resulted in his seizure and later death. Being away in Nafpaktos also helps in this regard as well as it keeps him away from Parry for some time and away from the swamps around Missolonghi. That all said, Byron’s health was never great to begin with, and the constant stress of working in Revolutionary Greece was not great on his health both OTL and TTL. While he will live longer than OTL, I cannot say at this moment how much longer, mostly because I haven’t decided yet, but this is not the last we will be seeing of Lord Byron.

[7] In OTL, Lucas was a Greek boy whose parents had died during the war. Byron being the good person that he was took the boy in and cared for him, teaching him English, science, art, history, etc. When Byron died he left Lucas as the proprietor of his loans, loans which remained unfulfilled by the Greek government and Lucas unfortunately died in poverty several months later.

Byron at Salona

In the months that followed his arrival in Greece, Lord Byron became increasingly distressed by the growing factiousness of the Greeks. Though the war against the Turk had done much to suppress the old rivalries and tensions between the various clans and communities in Greece, by the Spring and Summer months of 1824 their united front had begun to ware off, much to Byron’s dismay. Unable to bridge the divide between the Greeks, Byron busied himself by riding through the countryside alongside his faithful, albeit entirely incompetent companion Pietro Gamba. His most frequent destination was Missolonghi where he had developed a budding friendship with Alexandros Mavrokordatos due to their shared interest in the arts and philosophy.

Mavrokordatos had been recalled to the area following a raid on Aitoliko by the Turks in late December 1823 and his arrival in Missolonghi proved to be a strong factor in Byron’s decision to land in Western Greece as opposed to the Morea. Lord Byron thought so highly of Mavrokordatos that he considered him to be the Greek George Washington. Their conversations often drifted from politics and the war to more pleasant topics like art, drama, poetry, and philosophy. While, he had come to respect Mavrokordatos as a friend, it was the Souliot Markos Botsaris who truly won Byron over by sheer strength of personality. Botsaris was a larger than life figure. Renowned for his integrity, a trait uncommon amongst the other Greek captains of the war, and his unflinching dedication to the cause was unmatched, Markos Botsaris was a truly noble and heroic figure amongst the Greeks. He was charming, bold, strong, and incredibly savvy, and while the legends swirling about him certainly overshadowed the real man, Lord Byron found the Souliot’s honesty refreshing. It had been their correspondence that led Byron to Greece in the first place.[1]

Despite his decision to land in Missolonghi and his desire to work alongside Mavrokordatos and Botsaris, other magnates across Greece continued their attempts to pry the Briton to their sides, with the most persistent being Odysseus Androutsos. Androutsos had been one of the chief architects of the liberation of Athens in 1822 and as a result of his success he had become a powerful actor in Central Greece. Androutsos was a talented leader, a skilled fighter, and a brilliant orator, yet his greatest flaw was his overly grand ambition. Coming to view Athens as his own personal fief, Androutsos began efforts to cement his rule over the city, an endeavor that brought him into conflict with the National Government in Nafplion. Despite his own talent and the support of the local Athenians, Androutsos recognized the necessity of strong allies if he were to effectively challenge the Greek Government. Having already seduced Byron’s longtime friend and fellow adventurer, Edward John Trelawny, and their colleague Colonel Leicester Stanhope to his side, Androutsos, believed he could similarly win over Byron and in doing so, lay claim to Byron’s vast resources.

Odysseus Androutsos (Left) and Edward Trelawny (Right)

The real boon that Lord Byron provided to the Greek cause wasn’t his military skill or his acumen with words, but rather, it was his enormous personal wealth and his personal philanthropy that made him an attractive sponsor of the Greeks. The Greek countryside under the Ottomans had been deprived of wealth for generations while the islands and cities flourished. The farmers and peasants of Greece became destitute and deeply impoverished leading many to seek a life as a klepht to provide for their families. In Ottoman Greece, it cost less to house a family for an entire year than it would to feed them for a month. Labor and housing were cheap but resources and commodities were not. With over half of the arable land in Greece under the control of the church, state, and local magnates, many people within Ottoman Greece were left to starve, or subsist upon a pittance of poor land. Those Greeks who found themselves in Constantinople or on one of the many islands tended to do better than their Morean and Rumelian countrymen, building lavish houses of stone and marble, but even their wealth paled in comparison to the opulence and grandeur of those in the West. The Greek merchants of Chios, Hydra, Psara, Samos, and Spetses had themselves only come into their wealth recently, smuggling large quantities of grain to Napoleonic France from Egypt.

The economic situation in Greece was made worse by the rampant inflation in the Ottoman Empire over the course of the 19th Century thus far. In 1815, the value of the Ottoman Piastres, the currency used throughout the Empire, had a value of 20 to 1 against the British Pound Sterling. By the time of Byron’s arrival in Greece in 1824, the Piastre had fallen as low as 50 to 1 against the Pound, a loss of over 50% of its value in less than 9 years. The war had done much to accelerate this process as the Porte, desperately short on available manpower in the first two years of the conflict, resorted to minting more coins to pay the exorbitant costs of Arab and Albanian mercenaries. As the war progressed, foreign currencies became more prominent across Free Greece to make up the difference of the devaluing Piastre, with the Pound being the most popular, but also the rarest.

The Greek’s themselves had little means of raising the funds necessary to finance a war beyond looting, as the collection of tariffs and taxes was nigh impossible in the war-torn country. What plunder the Greeks could gather from their victories was often divided amongst the soldiers and their leaders as recompense for their services, as the government often lacked the funds to pay them, with only a small faction being sent to the state.[2] The only real source of dependable income the Greek Government could rely upon were the donations, grants, and loans sent from their supporters abroad. Even these would not be enough as the Greek Government had spent a sum in excess of £600,000 in 1823 alone, much of which was spent paying the excessive prices needed to keep the Greek navy as Sea.

Lord Byron was one of these private donors as he spent lavish sums of coin on the arming and training of Greek partisans amounting to a small fortune. His first act in the war was to “loan” £4,000 to the Greek Government for the commissioning of 5 ships from Hydra and Spetses that would patrol the waters near Missolonghi over the Winter and Spring months of 1824, the very same ships that had aided in his arrival in Greece. Within weeks of his arrival in Missolonghi, Byron would give an additional £2,000 to the Souliotes in Cephalonia and another £2,000 in Missolonghi, although this amount was reduced to £1,500 thanks to the efforts of Markos Botsaris. Another £1200 were spent by Byron to fund the deployment of the Government troops to Missolonghi and the organization of the ‘Byron Brigade, a force of fellow Philhellenes and Diaspora Greeks amounting to roughly 300 men at its height in December 1824. Byron also made a pair of loans, to the sum of £1,500 first to Mavrokordatos and then to William Parry upon his arrival in Greece in early February. He even went so far as to sell his own home in Scotland, Rochdale Manor, raising a further £11,000 which he had every intention of spending on the Greek cause.

Byron had another, more important role in Greece aside from volunteer and philanthropist, and that was of a custodian and arbitrator of the London Greek Committee’s loan to Greece in 1824. On the 22nd of February 1823 Andreas Louriotis arrived in London to begin efforts to contract a loan with the city. London was the economic capital of the world in the early 19th century and as such it was the only place where the Greeks could amass the amount of funds they so desperately needed. Through the aid of the Philhellene Edward Blaquiere, Louriotis was introduced to a group of two dozen prominent businessmen, politicians and nobles, including Byron’s closes friend John Cam Hobhouse and Thomas Gordon. These men would in the following days form the London Greek Committee, an organization bent on aiding the independence of Greece from the Ottoman Empire. To that end, the Committee tasked Blaquiere with traveling to Greece where he would report on the state of the war in Greece and receive the permission of the Greek Government to begin contracting a loan with one of their agents. Returning to London in September, Blaquiere gave an incredibly overestimated account of the economic state of Greece and their viability in the war. When the Greek agents Andreas Louriotis and Ioannis Orlandos arrived in London on the 21st of January 1824, they immediately set to work hammering out the fine details of the loan contract.

The Crown and Anchor Tavern (Right), “Headquarters” of the London Greek Committee

After nearly a month, they reached an agreement. Greek bonds would be raised for the nominal value of £800,000, at a price of £100 per bond, that would be paid back at a 5% interest rate by the Greek Government. However, trouble soon arose due to the chicanery of the Committee, as the bonds were sold at 59% of the agreed value, bringing the actual amount of money that would be loaned to Greece closer to £472,000. However, this amount was buoyed somewhat by news of Lord Byron’s successes in Greece, boosting the bonds up to 67%, or roughly £536,000.[3] This sum was then reduced further by the retention of two years’ interest by the London Greek Committee, the repayment of Lord Byron’s earlier loans, and the payment of commissions to the negotiators, giving the loan a final total of £420,000, with an actual interest rate of 7.5%.