Author's Note: So this is a bit of a shorter than average chapter covering the geography and demographics of Greece's newly acquired territories. Coming up next will be an update on the new and improved Greek economy following the addition of these new provinces and all that sweet, sweet British coin they milked in during the Russian War.

Chapter 90: The (New) Lands and Peoples of Hellas

The unification of Thessaly, Epirus, the Ionian Islands and the Dodecanese Islands with the Kingdom of Greece was a truly monumental event in the history of the young state. The fledgling country would grow from a rather paltry 60,000 square kilometers in 1854 to a more respectable 91,000 square kilometers in 1857.[1] Under the 1857 Treaty of Paris, the frontier of Hellas would move northward by a considerable margin, changing by nearly 70 miles in east with the addition of Thessaly and more than 100 miles in the west with the expansion of Epirus. This massive change in the political landscape of the Southern Balkans would have tremendous effects on the region in the coming months and years, yet in 1857 the situation in Greece was quite exuberant following the Treaty of Paris, which would formalize the new borders of the Greek State.

Starting on the Gulf of Thermaïkós, near the port of Platamon; the new border would follow the southern slopes of the Olympus Range to the municipality of Livadi. From there, the border would extend southwest passing by the Kamvounia Mountains to the Antichasia Mountain range, where the frontier then shifts westward through to the Valley of Millia and the Valia Calda Valley. The border would then move northwestward, through the Pindus Mountains towards the Aoos River, reaching the river near its confluence with the Sarantaporos River. Lastly, the border would follow the Aoos northwestward to the municipality of Tepelenë, passing to the south of the Gribës mountain range and then proceeding onwards to the Adriatic Sea, ending near Mount Chika.

Despite this incredible gain for the Kingdom of Greece, there remained serious doubts over their extent. In the negotiations with the Ottomans over the final border, the Athenian government had made a considerable effort to claim control over the Vale of Tempe, the Meluna Pass and the Millia Valley owing to their highly strategic nature. However, owing to heightened Turkish resistance, British indifference, and French ignorance; the Greeks were forced to rescind their claims to the latter two passes in return for the Tempe Pass. This decision would leave a sour taste in the mouth of most Greek diplomats, as they felt spurned and betrayed by their Western Allies. As such, the annexation of Thessaly and Epirus would only strengthen the revanchism and irredentism of the Hellenes in the coming years.

Thankfully, the Enosis of the Ionian Islands with Greece was a much simpler process with the cordial signing of the Palmerston-Kolokotronis Treaty in 1855, which formally ceded the Ionian Islands to the Kingdom of Greece. This annexation strengthened Athens’ grip on the eastern Ionian Sea, whilst also securing a small window into the Southern Adriatic via the island of Sasona. Moreover, it represented the first expansion of the Greek State since its independence in 1830, providing fuel to the nationalist rhetoric of the Greek Government. Similarly, the inclusion of the Dodecanese Islands in 1856 would also have a significant impact on the geopolitics of the region as the Southern and Central Aegean effectively became a Greek lake in all but name. With its Enosis to the mainland, the Hellenic state gained effective control over all the islands and archipelagoes of the Aegean south of Lesbos and Limnos, providing Athens with tremendous influence over maritime traffic throughout the region.

In terms of strategic value and overall worth, however, the region of Thessaly is perhaps the most significant gain by the Kingdom of Greece in the 1850’s. By far, Thessaly’s most noteworthy feature is the Thessalian Plain which is the largest extent of arable farmland in the entire country. With its expansive plains and alluvial soils from the mighty Pineios River; Thessaly is hands down the most fertile province in Greece and arguably the entire Balkans. When combined with the upcoming agricultural reforms and infrastructure investments of the 1860's, Thessaly would soon become one of the most prosperous regions in the Kingdom and the breadbasket of all Hellas. In terms of mineral deposits, however, Thessaly is quite lacking, with only a few Hematite reserves in the south near the municipality of Almyros and a few small Chromium deposits in the Pindus mountains.

The mountains of Thessaly do, however, provide it with strong defensive barrier against any outside adversaries. Its northern flank is well protected thanks to the presence of the Olympus, Kamvounia, Khásia and Antikhasia mountain ranges, providing the Kingdom of Hellas with a strong bulwark against their Turkish neighbor to the North. While the loss of the Millia Valley and Meluna Pass to the Turks is regretable, Hellenic control over the Vale of Tempe is a significant boon for Greece's defenses. The eastern edge of the region ends at the Aegean Sea and stretches from Platamon in the North to the Pelion Peninsula in the South. The south of the province is delineated by the Pelion and Óssa Mountains in the Southeast on the Pelion peninsula, while the southwestern edge of the province is marked by the Óthrys range. Finally, the Western edge of Thessaly is established in the midst of the Pindus Mountain range.

Beyond this, Thessaly also brings with it various demographic and cultural benefits. Of particular note are the Monasteries of Meteora on the western edge of the province. Built atop massive pillars of rock, the Meteora Monasteries are home to numerous religious artefacts and iconography as well as various works of art and treasure adding to the cultural heritage of the nascent state. Similarly, amongst the Kamvounia Mountains in the north of Thessaly lies Mount Olympus, home to the ancient Hellenic Pantheon of yore. Although it’s peaks technically lie outside of Greece’s borders and it has long since lost any major religious connotations to the Hellenes, it still remains an important cultural and historic site for the people of Greece featuring a number of Christian monasteries and churches.

Thessaly also boasts the largest population of the new territories, with more than 270,000 residents at the time of annexation. Of these, almost all of them are Hellenes owing to the recent flight of the Turkish Chifliks and their predominantly Turkish or Albanian retainers. Despite this, there still exist a small number of Turkish communities within Thessaly, who were either unable or unwilling to depart with their countrymen in 1857. While not considered separate peoples, Thessaly also features sizeable communities of the Aromanians and Sarakatsani within its boundaries, with most residing either to the north of Larissa or in the valleys of the Pindus Mountains. There are also a few scattered Albanian and Slavic communities in Thessaly, although these are predominantly located in the north of the country and nearer the borders.

Similarly, the religious map of the region was overwhelmingly in favor of the Greek Orthodox Church as most of Thessaly’s Muslim inhabitants had left for the Ottoman Empire following the union with Greece. Nevertheless, there are a number of Muslim practioneers within the province, namely those followers of the Sunni sect of Islam who reside primarily in Larissa or the communities along the border. Most of these are ethnic Turks and Albanians, but there are a small handful of Muslim Greeks. While the former are often devout in their faith, the latter are decidedly less so and would steadily return to the fold of the Greek Orthodox Church in the coming years - doing so, either under peer pressure or after having a genuine change of heart.

In terms of occupation, most of the inhabitants of Thessaly reside in the countryside as farmers, just as their fathers and forefathers before them had for countless generations. However, by the late 1850’s a growing number of Hellenes had begun migrating from the countryside to the cities of the region. With the mass exodus of the Turkish elites and their hangers-on, Thessalía was left almost completely devoid of trained administrators, bureaucrats, clerks, financiers, and judges, who had decamped for the Turkish Empire.

Some of these openings would be filled by Greeks moving in from the South, but many were left vacant for the native Hellenes of these lands to fill. For the greatly impoverished Greeks and Albanians of Epirus and Thessaly, this vacuum was a great opportunity to better themselves and their families, with many hundreds, if not thousands of second and third sons flocking to the cities to fill these now vacant occupations. Even still, the population of the Thessalian cities remained quite low in the years initially following Enosis. For instance, the city of Trikala only held around 20,000 residents in 1860, while the next largest, Larissa only boasted 15,000 inhabitants. Despite these dramatic changes, agriculture remained the lifeblood of the Thessalian economy, with a clear plurality of laborers choosing to remain as farmers in the Thessalian countryside.

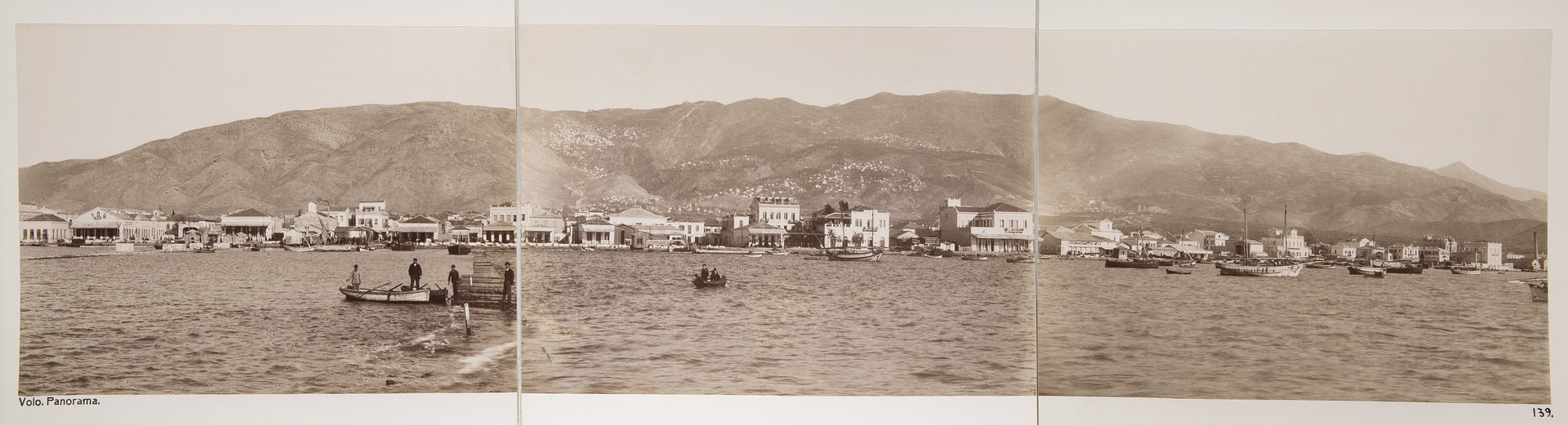

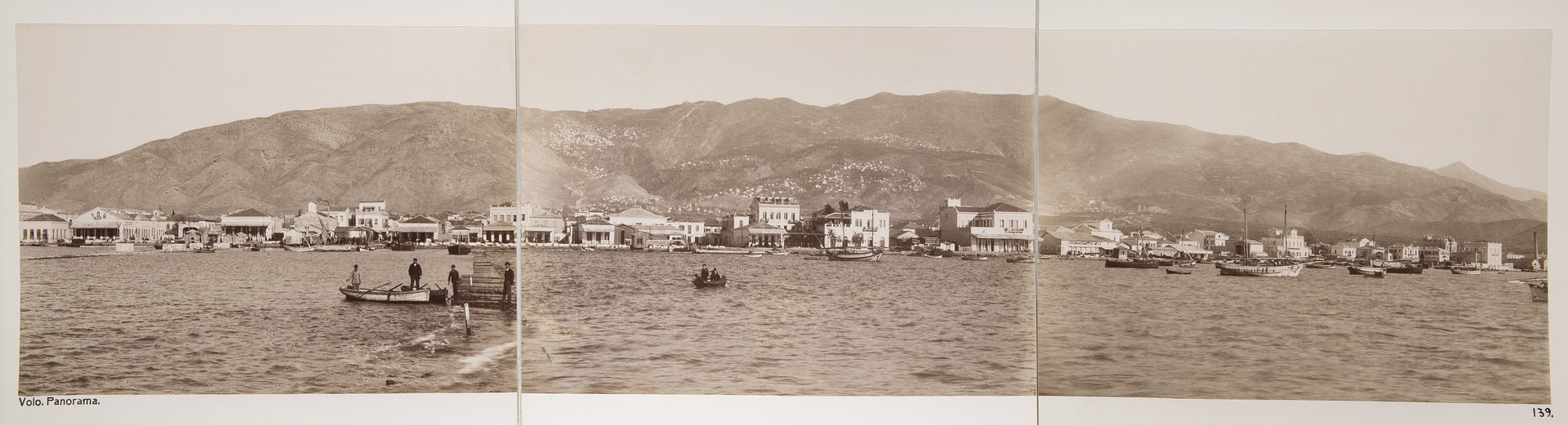

The Port of Demetrias (OTL Volos) would benefit greatly from urbanization in the 1860’s, growing from a meager fishing village to the premier port of Thessaly within a few years.

The region of Epirus in comparison offers very little to the Kingdom of Greece beyond its defensible borders and added population. Flanked to the north by the Ceraunian Mountains and Aoos River, and by the Pindus along its’ Eastern edge, Epirus is a truly rugged country. The climate in the region, like the rest of Greece, is hot year-round with short, but surprisingly cold winters made worse by the brutally cold Boreas winds. Unlike the rest of Greece, however, much of Epirus is actually quite lush owing to the preponderance of rains and storms during the Winter months.

Sadly, this is negated by the land's preponderance of mountains, which cover nearly all of Epirus, making it one of the most impoverished counties within all of Greece. Nevertheless, Epirus would be home to some 260,000 people who manage to eke out a meager living in the region’s many valleys, which tend to be more hospitable than the rest of the county. In fact, the valleys and foothills near Thesprotia, Ioannina and Argyrokastro boast more arable farmland than the rest of the region combined, resulting in their rise as the predominant cities in the province.

The valley of Ioannina in particular would possess nearly a fifth of Epirus’ entire population within its municipal environs, signifying the region's prime locale. However, even this amount pales in comparison to the 50,000 residents of Ioannina who lived within its walls during the pinnacle of Ali Pasha's reign, some 50 years prior. Situated on the western shore of Lake Pamvotis, Ioannina is in an idealic locale that receives the most rainfall on average in all of Greece, enabling it to support such a population. Some of Ioannina's residents would even rise to become prolific businessmen, bankers, and philosophical thinkers such as the famed Zosimades merchant family, Georgios Stravos - founder of the Bank of Hellas, and Athanasios Tsakalov - one of the founders of the Filiki Eteria. the same could not be said for the rest of Epirus, with most municipalities featuring far less than ten thousand souls, owing to a severe lack in available farm land to support such large populations. As such, most of the region’s inhabitants would resort to fishing, if they lived along the coast, or pastoralism, if they lived in the interior.

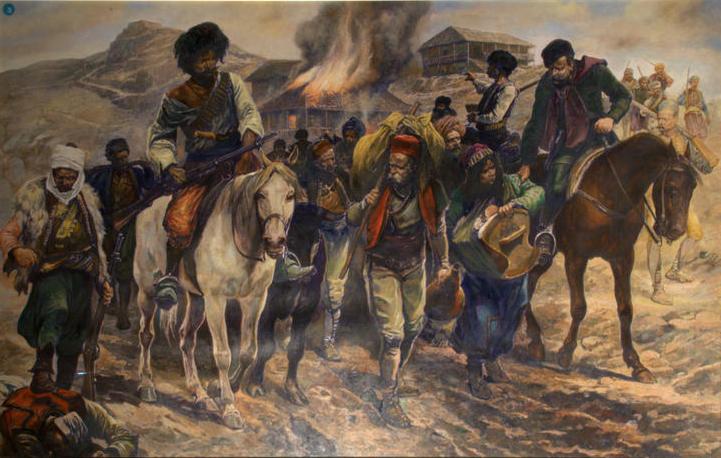

Sadly, not all parts and peoples of Epirus were quite so accommodating. The coastal region of Thesprotia for instance, would see periods of systemic violence between its Christian and Muslim communities over control of the municipality's limited farmland. Most of the time, these feuds were instigated by the Greeks who sought to drive out their Muslim neighbors, seeking to claim their property for their own. Naturally, the Albanians resisted, prompting several instances of bloodshed between the two communities. The Greek Government would make periodic attempts to peacefully resolve such disputes, however, owing to the general lawlessness of the region in the initial aftermath of its annexation, other issues of concern, years of pent up animosity, and the immense pride of both warring factions; these efforts would all fail. Ultimately, Thesprotia would see sporadic fighting for the better part of the next two decades until Athens finally ordered the Gendarmerie into the province in 1874 to put an end to the feud once and for all.

Scene from the Thesprotia Feud

The annexation of Epirus to Greece would bring moderate demographic changes to the region as the dreaded Chifliks were finally driven out by the local Greek and Albanian peasantry in 1857. Like Thessaly, many of their followers would also depart for the Ottoman Empire alongside their Turkish paymasters, leaving Epirus bereft of administrators and bureaucrats. This in turn enabled ambitious Greeks and Albanians to rise above their simple origins or change their course in life. This would naturally result in a degree of urbanization within Epirus, but also a significant amount of emigration as well. No longer tied to the land of their birth, most would travel to other corners of Greece seeking better opportunities for themselves and their families. A few hundred would go even further and departed for other lands in the United Kingdom, France or even the distant United States of America.

Ethnically, Epirus is more evenly split with Hellenes and Albanians comprising the two major ethnic groups within the region. The southern municipalities of Epirus are almost entirely Greek in language, customs, and creed. However, the further north in the province one goes, the more Albanian its persuasion becomes. Most of the Albanians of Epirus belong to the Cham and Lab communities, with both being most prominent along the Epirote coast. The Greeks of Epirus, in turn generally belong to the Epirote, Roumeliote, Souliote, Sarakatsani, Arvanites, or Aromanian communities. That being said, cultural differences between the two groups are almost indistinguishable after centuries of cohabitation and conformity brought on by the Sublime Porte. From a glance they would appear the same; they dress in the same manner, most practice the same customs and traditions - with slight variations between communities, and they share the same martial tendencies. Nevertheless, there does remain one major difference between the two communities: Religion.

The Albanians of Epirus are predominantly Muslim and belong overwhelmingly to the Sunni Muslim sect of Islam. However, there is a small, but influential community of the Bektashi sect found within the county, located primarily in the North of Epirus. There are also a number of Albanian Christians, belonging to both the Latin sect and the Greek Orthodox sect of Christianity. Most found on the Greek side of the border support the Greek Church, but there are a small number of Albanian Catholics in Greece as well. There is also a small, but vibrant community of Jews within Epirus, with most residing in and around Ioannina and the other major city centers of the region. Many of these people are members of the Romaniote community, easing their integration into the Greek state. In comparison, the Greeks of the region overwhelmingly follow the Church of their forefathers, the Greek Orthodox Church. While the expansion of the autocephalous Church of Greece into the Epirus would cause some concern initially, once it became apparent that very little would actually change on the ground for the faithful, the matter was promptly forgotten.

Members of the Romaniote Jewish Community

Sitting at the Southeastern edge of the Aegean; the Dodecanese, or "T

welve Islands", are an archipelago of over 100 islands ranging considerably both in size and scope. The largest and most prominent of the Dodecanese Islands is the island of Rhodes, located almost directly across from the Anatolian port of Marmaris. Thanks to their prime strategic positioning along multiple trade routes, Rhodes and the Dodecanese developed into bustling centers of commerce during ancient times. Even though its significance has waxed and waned over the ensuing centuries, its importance as a trade center remains intact to this day, lending Rhodes and the Dodecanese a sizeable amount of influence over the surrounding sea lanes.

Compared to the mainland, the Dodecanese Islands would see little social upheaval, owing to the reduced prominence of the Chifliks in their archipelago. Nevertheless, the exodus of their Muslim overlords from the islands, along with many of their attendants and the Ottoman bureaucrats, would lead to some upward mobility for the predominantly Greek lower and middle class of the Dodecanese, although this was a far cry from the changes seen in Thessaly and Epirus. By 1860, the population of the Dodecanese was almost entirely Greek and of Orthodox denomination. However, there did exist a small remnant of the Ottoman presence in the archipelago, with nearly a thousand Turks or Arabs residing on the islands after the departure of the Sublime Porte. Similarly, there are a few dozen Jewish families scattered across the Dodecanese, of which most reside in Rhodes. Overall, the Dodecanese Islands would add the fewest people to the Kingdom of Greece, with roughly 60,000 inhabitants scattered across the archipelago, of which nearly half resided on the isle of Rhodes.

The Heptanese Islands or "

Seven Islands" are perhaps the most valuable acquisition for the Kingdom of Greece after the region of Thessaly. While its population is less than that of Thessaly and Epirus at 230,000 people, most of these inhabitants are well educated and are head and shoulders above their mainland kin in terms of wealth and prosperity. Part of this can be attributed to the good geography of the region as it along with Epirus receives nearly three times more rainfall than the rest of Greece and it also sits along important trade routes between the Adriatic and Mediterranean. However, it cannot be denied that the Ionian Islands benefited from nearly forty years of British occupation.

Unlike their kin suffering under Ottoman rule, the Eptanesians enjoyed a number of political liberties and personal freedoms under the British including a relatively liberal system of government, limited representation on a local level, and a general respect for their rights and customs. The British also supported the establishment of schools across the islands, including the famed Ionian Academy in Corfu which was responsible for producing dozens of skilled doctors, scientists and lawyers over the coming decades. Moreover, the merchants of the Ionian Islands also had easy access to the British Empire's ports and the protection of the Royal Navy.

However, not all was well under the British as they vehemently opposed and violently repressed Eptanesian efforts for Enosis with Greece following the latter's independence from the Ottoman Empire in 1830. This would result in a number of radical political parties rising to the fore of Eptanesian politics, with the eponymous Party of Radicals being especially prominent. This political radicalism would not end with the Ionian Islands annexation to Greece in 1855, as it would later become a hotbed of Socialist agitators in the ensuing decades. Ultimately, the departure of the British in 1855 would result in a moderate shakeup of the political landscape on the islands, but owing to their more developed political institutions, the local Eptanesian politicians simply moved up to the national level avoiding much of the headache their kinsmen in Thessaly, Epirus and the Dodecanese experienced following their unions with Greece.

The Ionian Islands would have a pronounced effect on the Kingdom of Greece’s demographics, however, as included among their 230,000 predominantly Greek Orthodox inhabitants were a number of Catholic Christians. These peoples were either descendants of Italian settlers or local Greeks who had converted to the Latin Rite after generations of Venetian rule. Added to this were a number of Catholics in the Dodecanese, specifically the isle of Rhodes, a holdover from the old Frankokratia. When added to the preexisting communities in the Cyclades as well as the various Catholic immigrants that have arrived in Greece since Independence and the few Catholic Albanians in Epirus; the Catholic population in Greece numbers slightly over 20,000 people in total by 1860.

Of particular note is a small community of Maltese migrants scattered across the Heptanese islands (most of whom are on the island of Corfu). These settlers had come to the islands during Britain’s occupation of the islands; usually providing skilled labor that the locals could not. However, since the cessation of the Heptanese Islands to Greece, emigration from Malta has ceased entirely, with some families returning to Malta and a few others even traveling to Great Britain. Despite their relatively small size, the Maltese community has had a noticeable impact on rural Corfu, with several interior villages baring Maltese names, whilst many people from these parts were said to have spoken with Maltese accents and dressed in Maltese fashions. Sadly, they have long since assimilated into their neighboring Greek communities, although their influence on the local culture still remains in some aspects of the Eptanesian community.[2]

Next Time: The New Men

[1] Basically, Greece grew from around the size of Latvia to around the size of Portugal.

[2] The Maltese Corfiotes still exist in our world, but due to an earlier end of British rule the community would never grow to the same size as the OTL community.