Seven Shots: Part III

[This part is very long and mostly about alt-universe Ted Bundy. Clearly I listen to too many true crime podcasts.]

It remains nearly impossible, even today, to speak about the Evans administration without bringing up Ted Bundy.

Ted Bundy joined the Evans campaign in late 1971 as a twenty five year old University of Washington student. He brought with him a series of glowing recommendations from past jobs, most notably one as a Suicide Crisis Hotline operator in Seattle. It remains unclear exactly what role Bundy played during the early organizational days of Evans' campaign, but by the time he graduated from the University of Washington and joined the campaign full time he had apparently kindled a close and what would prove to be lasting relationship with Governor Evans.

Evans, initially considered a long shot, clung to those who had joined his campaign early even as he won his party's nomination and charged towards the presidency itself. Amongst those early joiners was Bundy, who proved himself resourceful and charismatic. As a result Evans trusted the young campaign aide with nearly everything, despite concerns from others that Bundy's youth and relative inexperience could prove disqualifying.

By all accounts Bundy acquitted himself well during the 1972 campaign, taking to politics with vigor and interest. His managerial style was considered somewhat disinterested, but he kept enough of a handle on the people under him that by the time Election Day rolled around and Evans was swept into office, defeating incumbent President Hubert Humphrey, Ted Bundy was quite well regarded by most of the people around him. Governor Evans kept him close, using Bundy's charm and good looks to his advantage, softening the blow of minor scandals and gaffes.

The estimated eleven women and girls who went missing in the various cities and towns that Bundy visited while campaigning during the summer and fall of 1972 would not be linked with the young Washingtonian until much later. Later, after his arrest, Bundy would claim that normally he killed at a rate of roughly one victim per month, with occasional gaps of as long as a year. During the campaign his killings had accelerated, to the point where by the end of October he was murdering one woman nearly every week.

The killings, combined with Bundy's strenuous campaign workload, meant that some of his later killings were rushed or sloppily hidden. At one point a fellow campaign aide discovered Bundy in a headquarters bathroom, scrubbing vivid crimson stains from the front of his shirt. Bundy explained the blood away as being from a nosebleed and nothing more came of the close call, even after a woman's corpse was discovered less than a mile away. One other victim survived Bundy's assault and managed to escape from the culvert he'd placed her body, though her description of the man who had attacked her was too vague for police to act upon.

His killings abruptly stopped after Evans' inauguration, as Bundy found himself locked down in Washington D.C. and kept under fairly close scrutiny. He was part of a presidential administration now, President Evans naming him Deputy Chief of Staff. This shocked many campaign insiders and Republican politicians, who had assumed that such a prestigious post would go to one of them rather than someone as young and inexperienced as Bundy.

But while Bundy privately resented the doubt he was shown, he was bolstered by the confidence of the President, who considered Bundy a close friend. Evans made use of his new Deputy Chief of Staff in many ways, some quite unorthodox. While Bundy was competent at organization and leadership, where he truly shone was with his interpersonal skills. Bundy could smile and cajole and schmooze with the best of them. So it wasn't too surprising for those inside of the administration when Ted Bundy showed up one morning in mid 1973 to deliver a press briefing, filling in for the incumbent Press Secretary, who was undergoing ankle surgery.

The press, who had been expecting the Deputy Press Secretary, were quietly surprised to see a young man in his mid twenties representing the President of the United States. Those who had covered the Evans campaign closely during the election were more settled. They knew Ted Bundy. They knew what to expect. And so Bundy's performance was well received, the President quietly hoping that it would help draw young voters to the GOP. Where the image of conservatism was often conflated with old, out of touch country club types, Bundy was something different. He certainly dressed like a conservative politician, but his speech was occasionally informal and even jokey. He called the reporters in the press pool by their first names and inquired after the families of the ones he knew from the election.

He practically blinded everyone in the room with pure charm and, by the time it was all over, some were already calling him a wunderkind. Bundy bathed in this positive attention, eagerly accepting the chance to do more press briefings...and indeed everything that would land him in front of a camera or a crowd. He introduced President Evans at events, checked over speeches, responded to the press, and even took part in a number of legislative meetings between Evans and congressional leadership.

But where Evans openly adored Bundy, many high level politicians were more suspicious. Senate Majority Leader Mike Mansfield went so far as to call him 'a little Rasputin' in private. The nickname stuck. Bundy

hated it.

His pique at facing actual pushback from political opponents was soon intensified by something unexpected. President Evans, though he liked having Bundy squirreled away in a position where he could be used for nearly everything that needed doing, was also facing some resistance from members of his own party. They didn't like that Bundy was being so high profile. Whether this was motivated by jealousy (which it almost certainly was) or professional concern, Evans knew he would need to listen to them. While Bundy was quite well liked by Evans and much of the White House staff, he was seen as something of a show-offish pretty boy by congressional leadership of both parties.

Evans decided that if he was to stick Bundy in one role, he might as well continue making use of his skills. In November of 1973, nine months into his administration, Evans asked Bundy if he would like to become Deputy Press Secretary, with the implicit understanding that he would get the top job after the 1974 midterms.

Bundy was shocked. He had become accustomed to taking a more rambling path through the White House, and to have his power limited was horrifying. He had also expected to become Chief of Staff one day, and while Press Secretary was certainly a powerful and very visible position, it barely held a candle to the level of

control that came with keeping track of who saw the President and when.

Bundy accepted Evans' proposal, his political skills were sharp enough to overcome his pride, but less than a week later he began killing again.

His m.o. for these later crimes were somewhat different than his earlier killings. In 1972 and before, Ted Bundy's method of finding a victim was to simply ask a woman for help with something. He would pretend to have lost his keys, or he'd have his arm done up in a sling and would pretend to fumble with a large stack of books while unlocking his car. If anyone suitable stopped to help then he would make sure they were alone, knock them unconscious and then drive somewhere secluded to finish his atrocities.

But now Bundy knew he could no longer do that. His face was on the cover of newspapers and his appearances in front of the country in the form of morning press briefings were becoming more and more frequent as the actual Press Secretary prepared for retirement.

The Bundy killings of 1973 followed a more nocturnal, brutal progression of events. Bundy would locate basement apartments with street level windows. Many of these did not have bars in front of them, and once he was certain that young women lived in them he would force the lock on the window, slip inside and bludgeon his victims to death. He killed at least four this way throughout the rest of 1973, though the actual total is likely higher.

But though he was careful to remove all incriminating evidence of his presence from the scenes, his compulsion to kill left other traces.

For one thing, he almost always drove. Upon taking an official job at the White House, Ted Bundy had bought a shiny black Mercedes. While this didn't stand out in the Georgetown neighborhood where he lived, the sight of such a car in the rest of Washington, especially in the middle of the night, made people take notice. As did the fact that Bundy's nightly outings didn't go unnoticed by neighbors and journalists alike.

The general assumption was that Bundy led something of a playboy lifestyle, and he was happy to allow these rumors to flourish. While it took the attention of journalists away from him, Bundy's neighbors were annoyed by the sound of his car leaving and arriving in the middle of the night. He was confronted more than once, though Bundy simply ignored their requests that he be more quiet. And in the White House itself, his work ethic began to slip. Having been limited to Deputy Press Secretary, some of the fun and allure of politics had begun to drain from his situation. Bundy began to act more disinterested while in the office. His press briefings acquired a sharp, unpleasantly arrogant edge that displeased President Evans. His administration was on shaky ground in terms of overall popularity, and while he had promised to end the war in Vietnam and fix a tottering economy, the overall perception was that he hadn't managed to get much done.

Overall, Evans had done some excellent things. He had, with the help of Vice President Ray, passed a nationwide recycling guarantee program for cans and bottles, promising five cents per can/bottle that a citizen turned in to be recycled. While this undoubtedly cut down on litter and did demonstrably prove to be something of an unintentional universal income amongst America's homeless population, it wasn't exactly the sort of thing that secured reelection.

And the Democrats were raring to take him on. Former Vice President Fred Harris, presumed front runner for the nomination in 1976, proposed ambitious reforms that seemed, to many Americans, to be much more exciting than whatever Evans was doing. Early polling showed Harris with a slight but persistent advantage.

In that environment the last thing Evans needed was a confrontational Deputy Press Secretary. He warned Bundy to pull himself together. Bundy promised that he would, but internally a coal of rage had been stoked. In February of 1974 Ted Bundy killed four people and left another in a coma, her skull fractured. At times he would spend much of the night with his victims, emerging only to rush to the White House...where his work continued to slip.

Meanwhile, Bundy's neighbors officially called a noise complaint on him, which had to be investigated by the police. Bundy, charming as ever, apologized to the officers and accepted a warning. No fine was levied, the police had no intention of actually taking on a White House official over something as minor as a noise complaint...but as they left one of the officers took notice of Bundy's car.

It was a distinctive, lovely car, with white walled tires that contrasted the car's sleek black body.

It also matched the description of a car seen cruising through a neighborhood shortly before a pair of murders less than a week before. While the officer didn't voice his suspicions, after all, there was no way the culprit was the White House's Deputy Press Secretary, he did take down Bundy's license plate number.

When Bundy killed again two nights later, once again a black Mercedes with white walled tires was seen near the scene of the crime.

This wasn't the end for Bundy, however. While the police were beginning to believe that the myriad killings of the past few months were in fact being committed by a single individual, they had no eyewitnesses. The sole survivor of the killing spree as they knew it was still in a coma. All they had to go off of was the car.

As the spring of 1974 progressed, Evans decided to take Bundy aside once more. He then offered Bundy something big, knowing that otherwise his Deputy Press Secretary would just continue to get more and more disaffected with his work. The big thing that Evans offered Bundy was the announcement to American press that the United States was once again engaging in serious negotiations with the North Vietnamese.

For the past few years the South Vietnamese government had effectively been limited to the cities and a few corridors of land that ran between them. The countryside, while it was recognized as South Vietnamese soil, was unofficially owned by the VietCong, who had begun to rebuild and recover from the disastrous Tet Offensive of 1968. The situation was effectively a stalemate, with ARVN and American soldiers (of which there were 20,000 in Vietnam as of 1974) mounting only punitive raids into the countryside, the NVA and VietCong doing much the same. Both sides knew that nothing good would happen if they did anything more serious.

For the North the main reason to negotiate was the continual bombing of their cities and roads. Organized infrastructure in much of North Vietnam was a distant memory, and while the country continued to function, the government knew that eventually their citizenry would begin to question the costs. Perhaps not before the Americans gave up...but they didn't especially want to run that risk. The ARVN were simply too well equipped to be easily overrun, and the Americans were still committed to defending them with airpower if not infantry.

The announcement that negotiations were coming for the first time since the fall of 1968 was a shot in the arm to the Evans administration...and Bundy as well. He leapt into the role with vigor, eager to make his mark on history.

Unbeknownst to him, the police were beginning to close in. They'd compiled a list of black Mercedes registered to people in the city, and while it was intolerably long (as was to be expected for Washington D.C.), the officer who had responded to a certain noise complaint at Bundy's residence two months earlier added his inferences to the investigation. They were immediately discarded. No way the killer was the White House Deputy Press Secretary.

But the officer, troubled by this, decided to go and investigate further. Returning to Bundy's street, he spoke to the Deputy Press Secretary's neighbors, who were more than happy to tell him that Bundy was fond of going out late at night and roaring off down the street without the slightest concern for anyone around. Certain suspicions confirmed, the officer requested they call in when Bundy made another nightly outing.

Their call came two nights later...as did another murder.

Armed with this alarming coincidence, the officer confronted his superiors, who once again warned him to leave it alone. Was he a Democrat or something? Why was he trying to mess with the White House?

Rankled, the officer decided to take matters into his own hands. But even as he did so, word was reaching the White House that maybe Bundy was a suspect in a murder investigation. It didn't take long for this to make its way directly to President Evans. Evans, already facing condemnation from elements of his own party over the upcoming negotiations with the North Vietnamese, cast the possible allegations against Bundy aside as spurious. There was no way Bundy was a murderer. This was nonsense coming from Bundy's political enemies, Evans concluded. Especially since the police didn't officially have Bundy listed as a person of interest in their case.

And besides, Bundy was doing much better now. Whatever funk he'd been in before seemed to have worn off.

But still the killings continued.

By early April they had made the jump from the police to a public matter. At least eleven were dead, one more still locked away in a coma, and very possibly there were more missing. The press gave the killer different names, though 'the Mercedes Maniac' seemed to stick best. But though there was rising fear around the killings, the police didn't seem to know much of anything. Only that the killer targeted women in their late teens and twenties...and that he drove a Mercedes with white walled tires.

By now Bundy had changed out his tires, but for whatever reason he kept the Mercedes itself. It seemed to give him a perverse pleasure to drive to and from the White House in the very vehicle that delivered him to his murders. Another aspect seemed to be the fear.

By the time negotiations with the North Vietnamese began in mid May of 1974 (with hopes of being wrapped up in time for the midterms) Bundy was feeling just fine again. He would do excellently as Press Secretary, he decided. He would do excellently, then perhaps when Evans was reelected the President would see fit to place him in another position...like Chief of Staff.

As he drove away from his apartment, on his way to another murder...Bundy didn't realize that he was being followed.

The Washington D.C. police officer who had first suspected Bundy of being behind the Mercedes killings had been continually stonewalled and even threatened by his own superiors of the past two months. It was only after he was threatened with a demotion that the officer went silent. But his silence didn't equal inaction. For the past week he had cased Bundy's apartment, waiting for the man himself to go for a drive. It was only now that he did so. The officer, in plain clothes and behind the wheel of his civilian vehicle, followed at a discreet distance, mouth dry, heart in his throat.

Bundy drove aimlessly for some time, up and down streets, slowing at some points, stopping entirely at others. It was difficult to tail him, and every so often the officer had to pull over. But Bundy didn't seem to be looking for tails. Rather, he was examining windows and doors. The barred ones he ignored entirely, but every so often he seemed to make a note of something in a little green book.

He returned to his apartment an hour later and the officer left, disappointed but still convinced that Bundy was exactly the person he was looking for. The next night, Bundy went out again...and again the officer followed. Bundy took a similar route, and once again stopped and looked at certain windows. If they were still lit he left them alone, but then, suddenly, the black Mercedes came to a stop.

Bundy exited, holding something under one arm. It took the officer a moment to recognize it as a fire poker, the sharp end removed, the iron wrapped with thick layers of electrical tape. Proceeding to a darkened street level window, Bundy knelt and began to fiddle with the lock. And at that moment the office leapt from his car, revolver drawn, and raced towards Bundy, shouting for him to put up his hands.

Bundy, startled, fell over, the poker clanging into the gutter. The officer, announcing who he was, demanded that Bundy put up his hands. Bundy went for the poker and a struggle ensued, the office coming out on top. Wheezing, his nose bloodied, hair mussed, Bundy stared up into the black barrel of the officer's gun.

"I really wish you'd killed me." He said.

The little green book contained lists and lists of addresses, some crossed off, others marked with little notes. 'Bars inside'. 'Bitch'. 'Negro'. And so forth.

And beneath the front passenger seat, carefully hidden away in a little tin box, were one hundred carefully sorted Polaroids, most showing Bundy's victims and just what he'd done to them.

On May 17, 1974, just past four in the morning, Deputy Press Secretary Ted Bundy was arrested for the murder of at least eleven women.

The news hit the White House hard. President Evans sat in stunned silence for several moments, looking over the black and white copies of the Polaroids the police had recovered from Bundy's car. He seemed to age at least ten years before he put them down. Looking up from the grisly parade of horror strewn across his desk, Evans quietly fired Ted Bundy, then buried his face in his hands.

Ted Bundy himself was weirdly calm, gaze directed to middle space straight ahead of him as he was processed and fingerprinted. The officer who had arrested him stood off to the side, watching Bundy closely. Bundy didn't spare his arrester a single look. When he spoke it was only to ask for his lawyer, who promptly came. At this point Bundy became more animated, sitting reassuredly back in his chair, cuffed hands folded in his lap.

"This is nothing," Bundy said, "all a bunch of lies."

His lawyer said nothing, just began to open his briefcase.

"Dan [Evans] will pardon me." Bundy insisted, clearly made uneasy by his lawyer's silence and grim expression.

No such pardon was coming. Not in a million years. It took the White House Press Secretary exactly three hours after Bundy's arrest to draft a statement condemning him as a murderer, a charlatan and an overall degenerate. President Evans offered his deepest condolences and apologies to the victims. It was all he could really do. He was heartbroken, betrayed and distraught, his trust in Bundy shattered into a million pieces.

Learning this from an isolated cell (the police feared he would be murdered by the other prisoners if he was put in a general population holding cell) Bundy felt something snap inside of himself. When the police came to ask questions, he dismissed his lawyer.

"He knew." Bundy said calmly.

"Who did?" Asked the officer leading the investigation.

"The President," Bundy said, "he

knew."

This assertion made by Bundy was almost certainly a lie, but it had an unpleasant tinge of truth to it. Representatives of the D.C. police department

had come to President Evans to share their concerns about allegations being made about Bundy. This had been mostly to assure the President that they didn't believe a word of it, but the nuance of the meeting hardly mattered...and the police weren't about to clarify, not when it turned out that they had been badly wrong.

The overall image that spun clear of the chaos was that Evans had known the police were looking into Bundy...and had decided to trust Bundy anyway. And as a result of that decision there were now eleven people dead and one more in what was probably a permanent coma.

Evans' approvals imploded. The North Vietnamese negotiations continued, but hardly anyone was following them. A major administration official, a close friend of the President, was a serial killer. And not only a serial killer, but perhaps one that had killed as many as twenty or even thirty people all across the country. Police departments all over America traced where Bundy had been throughout the 1972 campaign and reopened cold cases. The number of possible murders attributed to Bundy exploded briefly into the triple digits before being weaned down to a more reasonable (but still horrifying) thirty four cases.

Bundy, caught dead to rights and with no possibility of escape or pardon or bail, confessed outright to twenty one of them...the murders the police already had photographic proof of. His total confessions, covering method, location and rationale, would last for more than one hundred hours.

Meanwhile, the President strenuously denied any wrongdoing with regards to Bundy. If he was guilty of collaborating with Bundy, then so was the entire press pool, and the entire White House beyond that. Already resignations amongst staffers were in the double digits, and rising daily. The Evans administration was sinking, and nobody wanted to be onboard when the sea finally came rushing in.

On May 30, 1974, a little less than two weeks after Bundy's arrest and the subsequent implosion of President Evans' administration, congressional leaders (mostly Democrat, but with some stray Republicans attached) privately told the White House that they would likely be pursuing impeachment, and every indication spoke of them having the votes to do it.

Evans lingered for a day more, then resigned on August 1st, a broken man.

This left Vice President Robert Ray, formerly the Governor of Iowa, in charge of a deeply traumatized nation. Ray immediately announced his intention to be nothing more than a caretaker President, and explicitly denied that he would be running in the 1976 election. Everyone and everything in the Evans administration, he all but outright stated, had been tainted by the Bundy scandal and could not be expected to carry the country any further forward than the previous election had dictated.

He then settled down, determined to be as quiet and unoffensive as possible. This didn't stop some congressional Democrats from openly wondering if maybe he had known about Bundy as well, but Bundy said nothing. Ray didn't interest him, all he had wanted to do was destroy Evans in retaliation for the President's 'betrayal' of him. Now that that was done, Bundy focused on facing his upcoming murder trial. There were existing motions to extradite him to states that had the death penalty, so that he could be sent to the gas chamber...but for the moment all of that was up in the air.

President Ray, seeking stability, selected Senate Minority Whip Robert Griffin to serve as his Vice President. Griffin reluctantly gave up his Senate seat to answer the call, deciding that it was more important to help stabilize an ailing country than it was to pursue more political power.

Ray's caretaker term was largely quiet. The negotiations with the North Vietnamese ended with a fairly lukewarm peace between the two Vietnams. In practice this meant a return to more or less the status quo...though the NVA was no longer allowed to openly attack ARVN or American installations. The VietCong were left more or less to their own devices, though they remained heavily supplied by Hanoi. In return, American bombers no longer darkened the skies over North Vietnam, and the country cautiously began to rebuild.

Ted Bundy's trial was broadcast all across the nation. At first the former Deputy Press Secretary attempted to charm his way out of trouble, then he halfheartedly attempted an insanity plea. But the conclusion was foregone the moment the judge called the trial to order. Bundy was sentenced to twenty one life sentences, to be served consecutively, with no possibility of parole. He would be murdered by his fellow inmates (allegedly with the aid of at least one guard) in 1975, after less than a year in prison.

The 1976 election, like the Bundy trial, was almost foregone. The nation knew that the Democrats would win. The Republicans knew that the Democrats would win. And, most importantly, the Democrats knew that they were going to win. With President Ray and Vice President Griffin having already vowed to sit the election out (which many Republicans thought was a real shame, since Ray was really a pretty good commander in chief) the Republican bench was only halfheartedly filled, mostly by conservative Republicans determined to shut the Rockefeller branch out for good.

Former California Governor Ronald Reagan immediately took an early lead with Republicans, espousing optimism and a crackdown on crime. He dueled with Kansas Senator Bob Dole and a handful of others...which allowed the genial Tennessee Senator Howard Baker to take advantage of the split conservative vote and win the nomination on the first ballot. While Reagan showed no interest in serving as Baker's running mate (which Baker immediately asked him to do), he did suggest one figure who he quite liked.

That figure, Gerald Ford, also gently declined, but in turn brainstormed with Reagan and Baker to select a good conservative running mate. Someone strong on crime and defense, and from a key state.

Yes, they agreed. Donald Rumsfeld would be their man.

The Democratic race was simpler, sewn up by former Vice President Fred Harris before the primaries were even halfway over. Beating a handful of others, he settled into position as the party's presumed nominee but remained short of a veep, genuinely unsure who to choose. Initially wanting to simply let the delegates decide, Harris accepted his nomination and then settled back to listen to the keynote speech, which was to be given by a congresswoman from Texas, Barbara Jordan.

Harris knew of Jordan but had been out of congress during her time in it. The keynote was the first time he's ever heard her speak and he was immediately transfixed. Glancing to his campaign manager, Harris nudged his shoulder.

"Her," he said excitedly, "we're picking her."

Though some campaign officials were concerned by the idea of picking a black woman to serve on a major party ticket, Harris bulldozed them aside and, propelled in part by her magnificent speech, Barbara Jordan became the first minority and first woman to ever be nominated on a major party ticket in the United States.

The campaign was pleasant and restrained. Nobody wanted to talk much about the Evans administration or Bundy or any of the mess. Instead there was talk of the future, of fixing problems and reforming the government. And on that front Harris was energized. He crisscrossed the country in a van, eschewing private planes and campaign trains. He denounced corporate greed and espoused a sort of left wing populism that most people thought had died with Huey Long and the Great Depression. But amidst the denizens of a shocked, traumatized post-Bundy post-Evans America, that sort of talk found purchase. Here was a man who was going to fix it. And he wouldn't bring aboard mass murderers to help him do it.

Though Baker tried very very hard, the Tennessee Senator knew in his heart that he was never going to win. Rumsfeld was more disappointed in the loss than he was, the Illinois congressman sighing sharply before turning and walking briskly out. Baker conceded gracefully, and went to watch Harris begin his work to, as his campaign slogan promised, make America great.

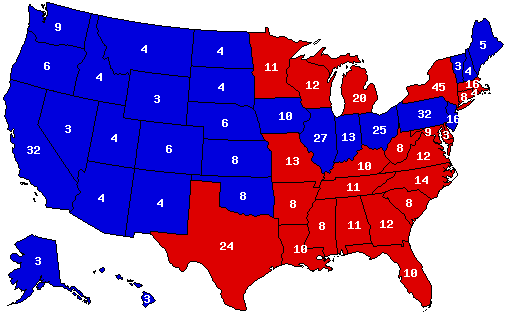

Former Vice President Fred Harris/Congresswoman Barbara Jordan - 389 EV 53.1% PV

Senator Howard Baker/Congressman Donald Rumsfeld - 149 EV 46.9% PV