You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Place In the Sun: What If Italy Joined the Central Powers? (1.0)

- Thread starter Kaiser Wilhelm the Tenth

- Start date

And now for something completely different!

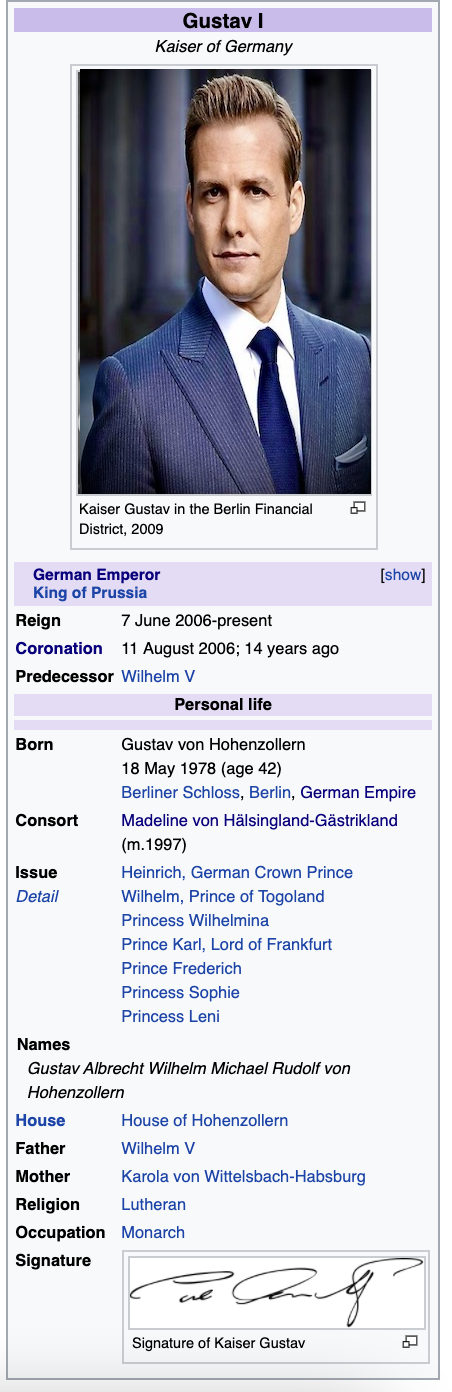

Inspired by the discussion a few pages ago about Germany's royal family, I made this wikibox shedding light on Kaiser Gustav I. It gives a few hints (but nothing too revealing) about what this world's like in the present. My Wikibox skills leave something to be desired.

Inspired by the discussion a few pages ago about Germany's royal family, I made this wikibox shedding light on Kaiser Gustav I. It gives a few hints (but nothing too revealing) about what this world's like in the present. My Wikibox skills leave something to be desired.

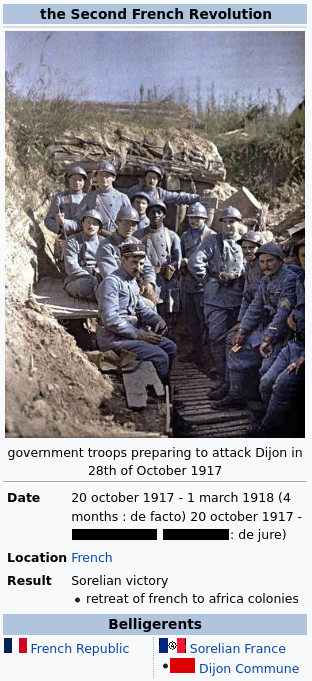

Chapter Forty-Three: The Second Paris Commune

"This will be the final revolution. I draw from two streams to create conditions uniquely suited to a French dictatorship of the proletariat. On the one hand, I draw from the Jacobins. The guillotine, doubtless, will return and the reactionaries will tremble before it once more. Yet, in the century and a quarter which has elapsed since the first revolution, a new stream of thought has infected political life. The people will finish now what Robespierre commenced all those years ago."

-Georges Sorel musing on the success of his revolution, spring 1918.

"We, my friends, are the true revolutionaries. Sorel would be best served nursing his wounds abroad, while propriety forbids me from opining on Comrade General Famride's revolutionary credentials."

-Ludovic-Oscar Frossard to his SFIO colleagues, January 1918

Losing the Great War had destroyed French cohesion. The Third Republic, having failed to defend la Nation, was now an object of scorn. It had sucked up Philippe and Jean-Paul in 1914, torn off one of their limbs in the meat-grinder, and sent them home to beg for worthless paper currency two years later. Urban workers blamed the regime for inflation and unemployment; rural villagers isolated themselves from the regime, dodging taxes and building self-sufficiency. Marxists believed defeat in the Great War to be a sign that the historically inevitable revolution was only months away; Catholics believed it was a sign of divine displeasure. Emile Loubet’s civilian government shambled on, a dead man walking, until October 1917. (1)

The Second French Revolution was both inevitable and the product of accident and miscalculation. On the one hand, the Third Republic had so disgraced itself that it was bound to fall at some point. On the other, the specific trigger for revolution was so small that Loubet cannot be blamed for preventing it. A jailbreak in Dijon escalated into a riot, and within weeks a rebellious growth had formed across France’s heartland. Soldiers sent to crush the revolt defected to it and elected one of their own as leader. If Jean-Jacques Famride provided the brawn, Georges Sorel was the brains of the revolt. A desire to see revolution first hand had brought the Marxist philosopher to Dijon, and his oratory had won him allies. Montbard, on the road to Paris, had given itself to the revolutionaries in late November.

Meanwhile, Paul Deschanel had been shooting himself in the foot. His Emergency Powers Act #3 (4) had turned France into a dictatorship, with censorship imposed and civil rights restricted. Though it suppressed action, it couldn’t stifle thought. Jumping at shadows did more harm than good. Every politician arrested for “disloyal” sentiment was a sign that the Third Republic had become a tyranny, that like a Tsar, Deschanel could destroy you for no reason. This made the Sorelians seem like a breath of fresh air. Still, secret police knocked on doors and carted people off to detention camps as sacrifices on the altar of the pagan ‘god’ Securité. This harmed Deschanel’s second goal, which was to gain foreign support for his regime. As one Swiss journalist put it, “that Frenchmen are fleeing the French government for the auspices of the German Army is all one needs to know about the situation!” Kaiser Wilhelm II found this quite amusing, and even quipped in private that, “I always knew I was a far superior leader to any frog. The good people of France, it seems, have come to their senses and are aware of strength and good character when they see it!” (5) Eventually, though, fear of an influx of potentially troublesome Frenchmen led to Germany, Italy, and Belgium closing their borders (while Spain and Switzerland established strict refugee quotas). Deschanel’s attempt to live down the embarrassment by claiming that these refugees were fleeing “anarchist Marxism” (6) fooled no one; Georges Sorel gleefully poured gasoline on the fire by highlighting the stories of people fleeing government-held areas to rebel held ones. That the franc wasn’t worth the paper it was printed on thwarted hopes of purchasing foreign arms. While no one had yet extended recognition to the Sorelians, no one was interested in intervention to stop them.

Deschanel was alone as events pushed the clock towards midnight.

The French Section of the Worker’s International- la Section française de l'Internationale ouvrière, SFIO- had been driven underground in early November. Paul Deschanel, appointed PM to crush the revolt, believed that giving the far-left a seat at the table in the middle of a Marxist revolt was asking for trouble. Arrest warrants were issued en masse, and much of the SFIO now languished in political prisons. However, the SFIO’s leaders had gone into hiding in anticipation of this. General Secretary Louis Dubreuilh had decamped for rural Normandy, while his right-hand men Ludovic-Oscar Frossard and Marcel Cachin remained in the capital in disguise.

Now, Georges Sorel wanted to meet with them.

Locating the leftist leaders proved challenging. The state of emergency meant that all mail was being read while crossing France without papers was difficult. Ironically, Dubreuilh was easier to find than the others- there were far fewer government informers in a Normandy village than in Paris. An SFIO agent entered La Motte-Fouquet- where Dubreuilh was living under an alias- in the small hours of 1 December 1917. Dubreuilh assumed the man to be a government spy and nearly killed him before he said a coded phrase revealing him as ‘one of us’, whence the General-Secretary fell over himself apologising. He’d been following the revolt as best as the censored newspapers would let him and was elated to hear that Sorel wanted to meet with him. That night, the two men began a roundabout journey to Dijon. Disguised as a priest (2), Dubreuilh walked and hitch-hiked down country roads, keeping a low profile. Considering that a month later, he was able to discard his Roman collar and enter Montbard, he must have played his part well enough.

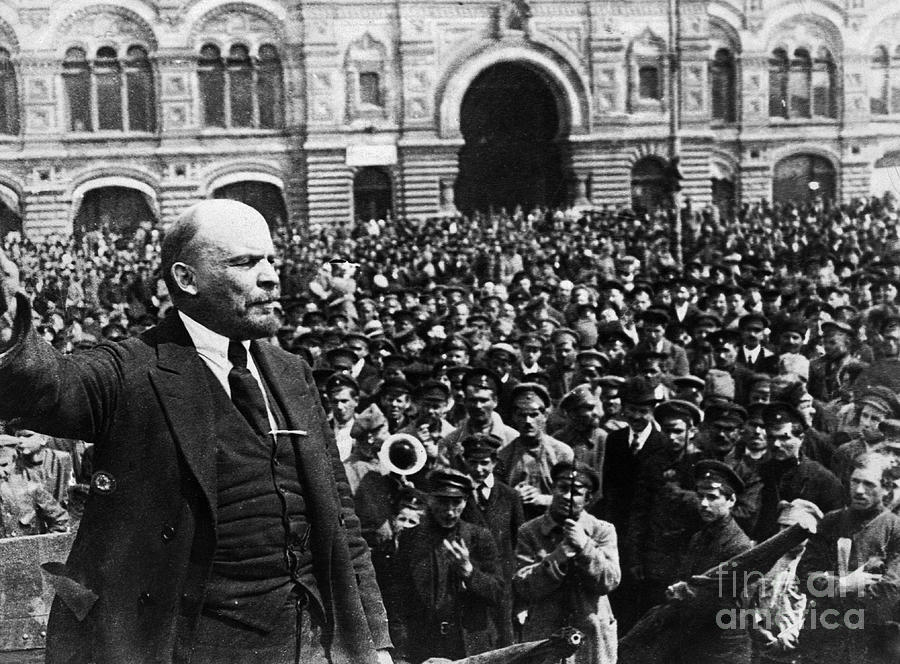

The three leaders of the French Section of the Workers International

From top to bottom: Louis Dubreilh, Ludovic-Oscar Frossard, Marcel Cachin

From top to bottom: Louis Dubreilh, Ludovic-Oscar Frossard, Marcel Cachin

Ludovic-Oscar Frossard and Marcel Cachin were easier to find. Both were bouncing around from one Parisian safe house to another under assumed names. The capital was full of SFIO men who both Frossard and Cachin knew. Frossard had shaved his moustache off and lost weight since being driven underground, and now travelled to Dijon without his glasses (judging stumbling around like a blind man to be a fair price to pay for security). Cachin, who was very attached to his whiskers (3), donned a mask for disfigured soldiers and pretended to walk with a cane- the SFIO agent who found him pretended to be his guide. Thus disguised, the French radicals travelled to Dijon.

Georges Sorel, who’d lost his left arm to a sniper at Montbard, wasn’t amused by Cachin’s faux injury, but was eager to get down to business. Meeting at his bedside (he was still recovering from his amputation), the four men discussed what the next steps were. Sorel wasn’t altogether comfortable. He had the loyalty of the Dijon rebels, but the SFIO men had far more political experience. Nonetheless, since it was better to befriend a rival centre of power rather than treat it as an enemy, Sorel emphasised what they could accomplish together. Would it be possible for the SFIO to call for a general strike to paralyse the Deschanel regime? How could the SFIO persuade soldiers to change sides? Dubreuilh wanted to know how Sorel’s men could help SFIO members in political prisons, while Cachin mentioned ideological differences between the two which would need to be resolved. The most important point, though, came from Frossard. Jean-Jacques Famride, he said, was clearly “pas un de nous”- not one of us. Sorel nodded slowly. “And what do you propose? He is a military man and I am not.” Ludovic-Oscar Frossard remained silent for a moment before saying, “Marx spoke of two revolutions, n’est-ce pas? One alongside the bourgeois-democrats, one against them.” This was code for collaborating with Famride during the fighting before turning on him. Aware that this conversation had the potential to turn explosive, Sorel changed the subject, but harboured similar thoughts. Famride was a rival, and it was reassuring to know that he’d have support in a struggle for dominance.

In the end, the men crafted a modus vivendi despite their differences. Sorel knew that the SFIO men were potential rivals but was willing to work with them for the power they brought. Meanwhile, the SFIO saw Sorel as an outsider. As veterans of the French far-left, they were determined to use the revolt for their own causes.

To this end, they decided upon a second Paris Commune.

Striking was illegal under Emergency Regulations Act #3, and the Parisian police had been working hard to prevent labour unrest from forming. In taking the easy way out- suppressing popular anger rather than treating it- Deschanel was sowing trouble. Convinced that steel could defeat hearts and minds, he’d ignored all advice to liberalise.

He was about to pay for that mistake.

* * *

Paulette Vidal dreaded going home. She could have taken a back-road, she could’ve slept rough. But there was no choice- she had to explain. Her father had charged Boche machine-guns for two years and, judging by his Legion d’Honneur, done a fair bit of damage. If he could put the fear of le bon Dieu into the invaders, what would he do here? Paulette crumpled the pink paper. Throwing it away would only delay the explosion until tomorrow. No, there was only one thing for it. Heart in mouth, Paulette pushed the door open and began the climb to her fourth-story flat. “Bonjour, papa! C’est moi!”

“Bonjour, Paulette.” Alfred Vidal was built like an ox, with a scar crossing his face. “How was the factory today? Come to think of it, today was your pay-day, n’est-ce pas?” He grunted. “And about time too. Here”- he rubbed his hands together- “donnez-moi.” Paulette handed him the money with her left hand, hiding the pink paper in her right. She tried not to look at where her father’s right leg had once been. “Only thirty million? Degoutant. How, Paulette, are we supposed to keep this family fed if they do not give you more? Why, the government gave me one hundred million last month for this”- he tapped his pinned-up trouser leg- “and what can I buy for that now? Absurd.” Alfred blew his nose on a 1,000,000-franc note with Deshcanel’s face on it. “And anyhow, my daughter, how is, er…” He gestured at her bulging belly.

“Assez bien, vraiment.” That was a lie- she’d been nauseous the whole day, and the baby hadn’t helped by kicking. No sense in making papa worry, though. He’d have enough to worry about soon. “Er, papa…”

“What is it, Paulette?” Her father’s eyebrows jumped up. “You are not ill, I trust?”

“The… the father spoke to me today.” Her father frowned. Every word had to be forced out, but Paulette carried on, her throat tightening. “The… the father. He said that, that… oh, papa! He said that because, well, I am carrying this baby, that he will not let me work any longer!” Tears ran down her face as Paulette handed her father the crumpled pink paper. “Oh, what are we to do?” She buried her face in her hands.

“That bastard! That utter bastard!” Just as she’d feared, Alfred Vidal hit the roof. His voice like rolling thunder, he called the factory foreman several things he’d picked up in the trenches as he waved his cane around furiously. She stood there, helpless and alone. “The swine! He is responsible for getting you into this mess. When you realised that you were carrying this child, he promised us that you would still have work. Now he proposes to throw you out and harm not just you and this family, but his unborn child as well?”

“I do not care about his child!”, she shrieked. “I care about us, papa! You said it yourself. A hundred million francs cannot buy a thing now and our savings are worthless. We shall have nothing!”

“We will see about this”, muttered Alfred Vidal. “We will damn well see about this.”

* * *

Poor Paulette’s story got out quickly. Many of her fellow factory girls, having suffered similar injustices, were sympathetic, and they staged a walk-out on 15 December 1917. Apoplectic, the foreman called the police. A “Dijonite disturbance” had broken out and needed to be crushed at once! It was a classic example of the Third Republic’s over-reaction. The image of mounted policemen wading into a crowd of striking women and swinging bludgeons around was a propaganda disaster. When SFIO men began shouting from the rooftops about the “massacre of innocent women”, people paid attention. Parisian workers viewed the mugshots of the arrested female strikers in the papers, and saw weary eyes, haggard faces, skin turned yellow by chemicals and hair turned grey by stress. In short, they saw themselves.

Instinct told the Parisians what to do next. Protests erupted the next day where the women were being held, calling for their release and for the foreman whose droit de seigneur had started this whole mess to be sacked- amongst them was the one-legged Alfred Vidal. This is where the SFIO came in. Chairman Louis Dubreuilh, Ludovic-Oscar Frossard, and Marcel Cachin had been lying in wait for an opportunity, and leapt at it like an animal ambushing its prey. How long, they asked, “are the workers to tolerate oppression of those like them in every particular, whose place they may take tomorrow?” The three men enjoyed the respect of the working classes and their words went far. Many joined the protests the next day (the 17th), while others held solidarity strikes. Paulette Vidal and her compatriots were nearly forgotten; what mattered was giving two fingers to the Third Republic.

Paul Deschanel was determined to quench the flames. Though he’s been justly criticised for his tendency to overreact, unrest in the middle of Paris was menacing enough that he can be forgiven for seeing Georges Sorel’s hand in this. He sent the police in at 10:30 AM. However, today’s protestors- who were mostly young men and greater in number than the previous day’s- fought back, and the police withdrew after half an hour. When they returned at noon, they found a terrifying sight waiting.

Barricades were going up in Paris.

The people had finally had enough. If Paul Deschanel was going to send armed men against them for having a sense of justice, then they would fight back. People donated bricks, furniture… anything a man could take cover behind. When the police captain in charge of the second attack, a man named Humbert, saw, he turned pale. “Les barricades- ils sont la révolution!” has been popularised, but “Merde!” is closer to the truth. Fighting raged throughout the afternoon, after which the police were repulsed again. The rebels- for that is what they were- now controlled two square miles of Paris.

The aptly titled Night of 17-18 December, painted six months after the fact when France was still in the afterglow of revolution, depicts men standing around a bullet-ridden red flag atop a barricade in a cobble-stone street. Silver moonlight illuminates the figures as they wait for a government attack. In reality, the night of 17-18 December was a bloody mess. Confused street fighting reigned as more barricades went up. Soldiers shot first and asked questions later; attempts to detain potential suspects only led to more violence. Deschanel had no more control over events than Georges Sorel hundreds of miles away. The fighting died down at midnight as both sides rested, but when the sun rose everyone returned with vigour. Street fighting ripped through Paris all throughout the 18th. Labourers defending their workplaces fired on any and all intruders; they were then treated as enemies by the Army men in the streets. Cognisant of which way the wind was blowing, soldiers defected en masse to the revolutionaries. For the second time in fifty years, the cobblestone streets of la ville lumiere were witness to violence. Gunshots replaced accordions; cordite replaced food and flowers. Chaos reigned.

The SFIO triumvirate had mixed feelings. On the one hand, all professed Marxism and believed revolution inevitable. By that metric, they told themselves, what they were doing was not just a milestone, it was profoundly moral. Yet on the other hand, they’d always been career politicians working inside the system. Socialism, to them, had meant Party congresses, political debate, and winning elections. Burning the system down felt, if not wrong, then alien. (9) Nonetheless, like Sorel in Dijon they had crossed the Rubicon of revolution. On the twentieth, the three declared themselves “representatives of the revolutionary working peoples of Paris”, who would “steer the ship of popular rule in a stable and prosperous declaration.” The city was declared to be under siege. Men young and old were conscripted into an “Armed Committee for the Defence of Paris”, supplied by opening the city’s armory. One of the paramilitary’s first tasks was guarding the city’s food supply- that was one thing the masses couldn’t be allowed to redistribute. Food was distributed three times a day under bayonet-point. However, no one was disconcerted by this. Paul Deschanel’s soldiers had guarded the granaries too, but to deny food to the hungry rather than feed them. The masses appreciated the regime’s “On Redistribution”, issued on Christmas Day. Anything which had belonged to “class enemies” (that term was never properly defined, so as to encourage a broad interpretation) was declared “the property of the people”. Chaos ensued as poor Parisians grabbed at the luxury they’d seen but never enjoyed. Wealthy urbanites who hadn’t fled were forced to watch mobs tearing through their homes taking what they pleased- fear and shame drove more than one aristocrat to suicide. Objets d’art which had survived the madness of 1789 fell victim to the mobs of 1917 while mansions were burned. That said, there were limits to the damage- most paintings and antiques, not being seen as worth destroying, survived, while the new regime took care to protect cultural sights. Once the initial pent-up anger of rebellion had been released, the destruction quietened as people of Paris had no desire to destroy their home city.

Rebels clash with incoming mounted police during the Second Paris Commune

Amidst all this, the main question amongst loyalists was, “Where is the Prime Minister?”

Paul Deschanel was dead. His mental health had been declining for some while (7), and the recent stresses of the civil war had proven too much. His last order had gone out at 10:30 PM on 17 December; his body was found at 4:15 AM on the 18th. Though his cause of death would formally be listed as heart attack, one cannot rule out the possibility that he killed himself, but was assigned a less ‘shameful’ cause of death for the world to see. (8) Président de la République Louis Marin took up his predecessor’s banner in Nantes. The war, Marin declared, would be fought to its successful conclusion, and “the integrity and structure of the French State thereby secured.” Events spoke louder than politicians. Apathy swept over France as the truth sank in. Soon, it would be Sorel and the SFIO who ruled over them, not Marin. People did their best to ignore his government, only acknowledging its existence to prevent it imposing its will on them. Soldiers continued to form councils and desert, peasants continued to eat their foodstuffs, not sell them, and the cities teetered on the brink of anarchy. The regime lacked the strength to crush the Second Paris Commune, much less advance on Dijon. Marin was fated to be one of those grey men whose failure to hold back the tide sums up the Third Republic.

Georges Sorel, meanwhile, was learning a great deal about how to fake a smile. Since the SFIO were his nominal allies, he had to applaud their seizure of Paris. Yet, they were his political and ideological competitors. While he’d taken Dijon and become bogged down in Montbard, a rival centre of leftist power had conducted a second Paris Commune. Yet because they shared a mutual foe in Deschanel, he had to treat this like a good thing.

A desire to outperform his rivals led Sorel to the most radical step of the Revolution yet.

On 1 January 1918, Georges Sorel issued another of his famous manifestos. The Second Paris Commune had only been the beginning. “After all, only two of France’s cities- Dijon and Paris- have liberated themselves thus far. Yet, how many are in France? How many metropoles with their teeming masses are left, waiting to be liberated?” A nationwide General Strike was needed to “bring the machinery of the Third Republic to a halt and establish national liberation for all of France.” People listened. The first week of 1918 saw walkouts en masse across the country. Trains stopped running, the factories stopped producing goods, and students were not taught as was left of France’s economy was killed by the very people who made it function. In certain key areas, mostly to do with energy production and basic transportation, the regime diverted badly-needed soldiers to force people to work. Train engineers did their jobs with an officer’s pistol to their heads; miners were escorted by armed men to ensure that government-held regions stayed warm. Aside from that, though, the Sorelians were right. Georges Marin lacked the soldiers to establish a military dictatorship, and so the general strike carried on. The harvest had already been brought in and farmers had enough for themselves- there was nothing to lose by bringing food to the cities (albeit less than in calmer years). In exchange, they received not a billion francs but something physical and tangible. France had been sliding to a barter economy ever since the spectre of hyperinflation came, and the new year saw this extended and deepened. One could eat a loaf of bread; one could merely blow one’s nose with a banknote. In such uncertain times, which had more value? Depending on the buyer, a farmer might get a pair of gloves, a hat, or brand-new horseshoes in exchange for two loaves of bread and a pint of milk. Thus, the city-dwellers of France found themselves with calories in their stomachs, minimal work, and a political vision before them. Montpellier, Toulouse, Nantes, Bordeaux, and other cities all found themselves gripped by riots as people turned on the Third Republic. The entire system was collapsing before Georges Sorel’s eyes like a colossus in an earthquake. “Urban councils” were declared in many places, with union leaders, local radicals, or the man with the key to the granary taking charge backed up by a few guns. Soldiers were attracted to these places like moths to a flame, wanting nothing more than to return home and forget that they’d ever had anything to do with defending the Third Republic. Rebel political commissars and soldiers were greeted with open arms as they integrated these towns into Sorel’s state. Young men flocked to the rebel army; many officers brought their units over en masse when they deserted.

The Third Republic died in February 1918.

Georges Marin was left broken by this. He hadn’t wanted the job of state president any more than Deschanel had wanted to be Prime Minister- adverse circumstances had forced it on him. Just like his predecessor, Marin had been forced to build a brick wall to keep the revolutionaries out of power, yet he had been given no straw. Despite his best efforts, Marin knew that his name would go down alongside Louis XVI, Napoleon III, Joseph Caillaux, Emile Loubet, and Paul Deschanel- Frenchmen who, through their failures, brought calamity on la Nation. (10) At 6 AM on 1 March 1918, he led his family and government aboard the destroyer Bouclier- the entire French Navy, down to the last ship, escorted them to Algiers. This was not just for security- dispersing the fleet across the North African coast would deny it to the rebels.

France was now divided. Valiant government units fought delaying actions all through the spring, francs-tireurs slipping into the woods to harass the new regime. Banditry continued to be a problem, as armed men decided to go their own way rather than submitting to Sorel. The Vendee, haven of monarchism during the Revolution, held out the longest- Comrade General Famride (as he took to styling himself) wasn’t pacified until the early summer. Yet, by the end of March the deed was done. Half a year after a Dijon jailbreak had sparked a riot, a red shadow had covered France. It remained to be seen what would happen next.

Across the Mediterranean, the Third Republic lay prostrate. Their own people had turned on them; the soldiers of France had proven bigger foes than the soldiers of Germany. Though France of course had a long history of regime change, this seemed different from the conservative perspective- never had so radical an ideology seized the mainland. Yet, shielded by the remnants of la Marine Nationale, the ancien regime survived. Though stalemate ensued for now, the Third Republic’s leaders were determined to neither forgive nor forget. In this, they were inspired by their cousins across the Atlantic, in la belle province de Québec. The Quebecois national motto- je me souviens- spread around Algiers like wildfire that spring and summer.

I will remember.

Comments?

- Chapter 17 reveals all…

- OTL, Zhou Enlai did this to get out of Shanghai in 1927, so there’s something resembling precedent.

- And rightly so!

- See chapter 23

- Because he’s Egoistic Kaiser Wilhelm II™! Incidentally, I’ve been reading The Guns of August as of late, and the first chapter is replete with little anecdotes depicting what a character Wilhelm was in OTL…. worth your time!

- I’m perhaps the furthest thing from a Marxist possible and even I can spot the contradiction here.

- As his Wikipedia article makes clear

- Less shameful from the perspective of someone in 1917, anyway.

- Especially Chairman Louis Dubreuilh- from what I can gather a reasonably conservative man within the Socialist context

- Caillaux was the Prime Minister who signed the Treaty of Dresden while Loubet was PM when the revolt began.

Dear Readers,

Someone (my apologies; I'm tired and can't remember who) commented on the unlikeliness of a German Emperor wearing civilian garb even in TTL's 2021. So, here we have Kaiser Gustav I photographed in his office.

Also, @CosmicAsh my already immense respect for you has increased tenfold. Making this gave me some indication of what you must've gone through for your (vastly superior) Larry Hogan edit.

Someone (my apologies; I'm tired and can't remember who) commented on the unlikeliness of a German Emperor wearing civilian garb even in TTL's 2021. So, here we have Kaiser Gustav I photographed in his office.

Also, @CosmicAsh my already immense respect for you has increased tenfold. Making this gave me some indication of what you must've gone through for your (vastly superior) Larry Hogan edit.

Last edited:

Chapter Forty-Four: Over Open Sights, Over Open Ocean

"As the trenches ran through Ypres, so the Mediterranean runs through France."

-Popular saying bitterly commenting on France's divided state

"Cadres come and take our food without paying. If we protest, we stare into the barrel of a gun, if we protest further, we are imprisoned. There is not enough to eat and none of our produce so much as reaches the cities, so it is all for naught. Do correct me if I am wrong, but I was under the impression there had been a revolution!"

-Excerpt from a letter of protest secretly circled around France, autumn 1918.

"You may write, you may dream. I do not doubt this, nor do I doubt their worth. But this is not theory, Chairman. If this enterprise of yours fails, the revolution fails and we shall be under Clemenceau's boot."

-Ludovic-Oscar Frossard imploring Georges Sorel to repeal Réquisition révolutionnaire

"I am the State. Now that one man is at the helm and politics rendered moot, the exiles of France may hope for a safe and secure society until such time as the mainland is liberated. No party nor political interests will ever succeed in throwing the ship of state off its course ever again!"

-Georges Clemenceau, boasting of his newfound power in private conversation

Overstating how traumatic the past four years had been for France is difficult. Losing Alsace-Lorraine and being humiliated with every glance at a map had reshaped the national psyche. As the Crusaders had striven to restore the Holy Land, so the French strove after those six thousand square kilometres. War had united all but the firmest radicals- including several of the men now controlling the mainland. If la Nation stood as one, they asked in summer 1914, surely nothing was beyond them? Surely?

Evidently not.

A fluctuating consensus of 800,000 has formed around the heaps of dead Frenchmen in the fields of Artois and Ypres, in the Alpine mountains and Libyan desert. (1) That was 800,000 young men who would never return home, 800,000 families irrevocably broken, a reduction of 800,000 in the workforce and tax base- slightly more than one out of twenty Frenchmen.

And for what? Those men had given their lives for the privilege of losing one-fifth of France’s landmass, the bulk of the navy, the worth of the franc, and the country’s honour. Instead of revenge for 1871, the French people had found a calamity to throw it into the shade. They had done their utmost, put everything they had into the war, and it had proven inadequate.

Given that the less comprehensive 1871 had destroyed Napoleon III, the surprise is that the Third Republic lasted as long as it did before collapsing.

German restrictions eliminated the trenches, the weeks and months of standing still in freezing rain and damp mud, watching eight hundred thousand of your countrymen die alongside you. The few set-piece battles all saw manoeuvre and morale dominate. Elan vital, the icon before which generals bowed in 1914, had finally come into play- except it was directed at them. Revolution, not modern war, swept through the streets like a giant vacuum, blowing the old regime across the sea to Algeria. The Third Republic meant war, hunger, misery, and an almost unimaginable shame. If they did not fight this beast, its unfitness to rule would consume them and their families.

For better or worse, the people now had their wish.

Eradicating the Third Republic had been the easy bit. Now the victors had to replace it. Philosopher Georges Sorel had transformed a revolt in Dijon into a revolution. Sorel’s eccentric past had taken him from Orthodox Marxism to syndicalism, while at the same time flirting with social conservatism. (2) His was the face on the poster, he’d convinced the masses with his pen, and he expected the lion’s share of power. General Jean-Jacques Famride complimented Sorel. (3) Famride was not a socialist; rather, he was the officer who’d been ordered to strangle the Dijon revolt in the cradle before his conscience led him and his men into Sorel’s camp, where he’d found himself the most senior military man. After winning a few key victories, Famride had spent the past few months trying to figure out how to turn the rebel army into a proper force. Since he wasn’t actually a socialist, Famride was seen as ideologically neutral and by extension, a potentially key ‘swing vote’ in any major decisions made. However, as commander of the most organised force in the country, his status as an unbeliever concerned some. If he deemed the new regime too radical, might he not move against it with all the guns in France?

This fear predominated amongst the last three regime founders. Louis Dubreuilh had led the French Socialists (SFIO) before the war; Ludovic-Oscar Frossard and Marcel Cachin had been his lieutenants. Their commitment to revolution was matched only by awareness of their own power. Although it had always worked within the system, the SFIO had been France’s largest socialist party for twelve years. Tens of thousands across the country respected General Secretary Dubreuilh, and it was his name which endeared prewar Socialist Party officials and voters to the new order. The SFIO troika was uneasy about the status quo. On the one hand, they were thrilled at opening the door to ‘socialist paradise’ (4) and ensuring their place in history- the intoxication of power sweetened this. Yet, as the afterglow faded they were left slightly disappointed. Georges Sorel had never sat in the Chamber of Deputies, never addressed the masses in whose name he claimed to rule, never sighed at an economic balance sheet or wondered what the people thought. While Dubreuilh had led the nation’s socialist movement, Sorel had been an eccentric recluse, growing pudgy as he slaved away at the study of theory. And now he claimed to lead them? As for Jean-Jacques Famride, well, he was a military buffoon whose only saving grace was in sweeping them all to power. If he vanished tomorrow, the SFIO chairman would not shed a tear. A coup d’etat was too radical to imagine, but so was settling for anything less than his perceived fair share.

These disparate personalities had to unite to give la beau patrie a stable regime.

The most pressing task was preventing another 1792, when Prussia and Austria had sparked twenty years of war with revolutionary France. Ejecting the Third Republic was one thing; repulsing a German-led counter-revolution would be another. What if Britain landed in Normandy while Georges Marin attacked from the south? Suppose Italy decided to advance its frontier to the Rhone? (5) Revolutionary France was surrounded by conservative monarchies and its central ideology demanded that workers of the world overthrow their kings for the new creed. Serious materiel shortages made a levee en masse impossible. Germany and Italy had overwhelmed the vastly superior army of 1914- marching to Paris would’ve been easy. As Jean-Jacques Famride admitted, the rulers would have to be mad not to intervene. If there was one thing European history had proven, said the general, it was that feuding monarchies could reconcile overnight if they found a common enemy- witness how the threat of revolutionary France had ended the ‘stately quadrille’ (6). The list of problems the new men could see were endless.

However, the new regime was in less danger than it might seem.

Jean-Jacques Famride’s comment was less accurate than first meets the eye. Diplomacy had been more fickle in 1792 and war had since become infinitely more costly. The war in Danubia, controlling the Eastern puppets, and subduing Mittelafrika distracted Germany. (7) No one wanted to extend the perpetual low-level insurrection in occupied France to the rest of the country. (8) Great War debt needed paying off while it took something as cataclysmic as the sack of Vienna for the public to approve sending troops south. Georges Sorel wisely refrained from calling for the Kaiser’s overthrow or stirring up the German occupation zone. Italy was waiting for an opportunity that would never come to extend its influence in Danubia. Britain’s sacrifice of youth to defend France had shaped the national consciousness, and the average Briton would’ve been repulsed at the idea of France being an enemy. Furthermore, Germany would’ve viewed British intervention as an intrusion on its sphere. Switzerland, Belgium and Spain had no power to act alone. No one respected the new regime, yet so long as Sorel kept to himself, they wouldn’t spend blood and treasure to kill him, and the state of emergency slowly faded. By the end of the year, Sorel felt comfortable enough to declare that “revolution is not always a linear process… peace is often a common interest shared between revolutionaries and counter-revolutionaries.” It was as much of an olive branch as Kaiser Wilhelm II would get but it was enough.

Germany now accidentally gave Sorel’s regime a chance at life. By late February 1918, the Third Republic’s days were clearly numbered. Berlin had no love for the regime, but neither did it want to see Marxists to its west. Thus, Ambassador Wilhelm von Schoen took a French destroyer to Algiers. Depriving the revolutionaries of recognition was supposed to harm their international image, but Georges Sorel turned it to his advantage. Since Germany wanted nothing to do with revolutionary France, he would have nothing to do with Germany. Therefore, all reparations debt under the Treaty of Dresden should be applied to the “Algiers clique”, not “the true France!” Kaiser Wilhelm faced a conundrum. He could recognise Red France to legitimise his claim to reparations, invade to secure them, or drop his claim. Recognising the revolutionaries was out of the question, and an invasion would’ve been more trouble than it was worth- some economists calculated that France physically lacked what Dresden required of it. Thus, Berlin was forced to accept Sorel’s unpalatable fait accompli. While officially demanding that the Algiers regime pay in full, German elites privately conceded that the money was “as far gone as our hopes for peace on the last day of July 1914.” Prime Minister von Heydebrand withstood savage criticism but always maintained that this was the best of bad options. Ultimately, out of the 65 billion in specie agreed to at Dresden, less than a quarter found its way into German pockets.

This gave the new regime a chance. The collapse of the franc had thrown millions into chaos, costing the Third Republic legitimacy. Communism won hearts and minds by promising to burn the system down. However, Sorel knew the problem wouldn’t vanish with a change of flags, and if he couldn’t increase living standards fast the people would turn on him. Talking his way out of reparations enabled him to create a stable economy. Sorel declared the Third Republic’s currency null and void as two trillion francs populaires rolled off the press (9). By the end of 1918, the franc populaire had overcome its teething troubles. Keeping specie in the country as opposed to shipping it off to Germany gave the communist currency enough support to be trustworthy- although real prices were still three times higher than 1914.

Other economic policies were less popular.

Sorel was determined to capitalise on revolutionary France’s first harvest. He remembered all too well that hungry urbanites had gone over to him because they believed he’d feed them better than the ancien regime. If Sorel failed them, they’d topple him. German occupation halved France’s grain farmland, but also reduced the number of bellies to fill. It would not be easy, especially without foreigners from whom to buy food, but Sorel believed a sustainable Communist agricultural programme was possible.

Sorel, Dubreuilh, Frossard, and Cachin issued their economic encyclical Réquisition révolutionnaire (Revolutionary Requisitioning) on 22 August 1918. It was an attempt to dictate not just the harvest but the entire French economy. Its lengthy preamble declared that with foreign foes occupying much of the nation’s best land, la Nation needed a supreme effort to feed itself, which would require “perfect harmony” between urban and rural areas. Government-appointed agricultural inspectors would frequent all farms to confiscate the vast majority of the produce and farmers would not be paid. In exchange, farmers wouldn’t be subject to taxation and their sons would be exempt from military service. “The farmer pays la Nation with his goods”, declared the elder statesman, “to ask anything more of those who feed us would be unjust.” These goods would then be processed at a local warehouse and shipped to the capital. Every month, the newly-created Ministry of Distribution would assess the goods and decide on a monthly distribution plan. From Paris, the goods would be shipped across nationalised railways to warehouses, where local Ministry of Distribution officials would feed the people. Urbanites received ration books which allowed them to purchase a certain amount of food. Purchase was key- while food was not inordinately expensive, the government expected compensation for the trouble it went to in distributing. Farmers were not issued ration books- rather, they were able to submit applications detailing their family size, ages, states of health, etc, and local Ministry of Distribution officials would use that to decide how much food to leave them.

Urban production was no less convoluted. Réquisition révolutionnaire dictated that all tradesmen register with a newly formed ‘national guild’ by the end of the month. These ‘guilds’ were not like their medieval counterparts- rather, they were organisations designed to run a nationalised economy. As an example, the abandoned Renault factory in Paris was integrated into the National Motor Production Guild ; the foremen and manager were state employees paid by the regime. Ironically, given that Sorel was a syndicalist, unions were forbidden. This was a major source of tension between the leader and the SFIO men. Now that the revolution was complete, Dubreuilh and his allies said, the workers had no reason to unionise because they already owned everything. Sorel retorted that unions would give industrial workers ‘a revolutionary spirit’ and could serve as useful tools for weeding out counter-revolutionaries. He believed his position as leader gave him the final word, yet the SFIO men refused to budge. In the end, Sorel conceded, but he fully expected a reciprocal concession. The debate over unions was the first spat in the leadership, but it would not be the last.

Georges Sorel’s hopes that this mess of paperwork (which was what the system ended up being on paper) would bring the French economy into glorious egalitarianism quickly disintegrated. Farmers hid food or exaggerated the number of people under their roof and banded together to chase food collectors away; more than one met a grisly fate in a vegetable patch. Local Ministry of Distribution officials furiously demanded to know why there was so little food and sent their collectors out again, often with instructions not to spend too long asking politely. This prompted further backlash, and soon collectors couldn’t go anywhere without armed guards. Government officials nicking their produce while armed men threatened their families reminded most peasants of nothing so much as the Third Republic. Collected food ended up spoiling in warehouses and freight cars. Urbanites weren’t pleased that they often could only purchase half or two-thirds of what their ration book entitled them to, while loathing the ‘guild’ system. They were supposed to own the means of production, yet all the directives came from a distant, bureaucratised central government and were enforced by government agents.

The biggest difference between the Third Republic and the revolutionaries, one Parisian bitterly remarked, was the colour scheme on the propaganda posters.

French farmers fill out the paperwork to ascertain how much food they should be left, autumn 1918. Contrast their haggard looks with the well-fed cadres.

Georges Sorel was confused. Years in the ivory tower had taught him that Marxism was perfect for industrialised France. Furthermore, surely the ‘liberated’ people would rationalise any sacrifices as being for the greater good. The same spirit which had got the country through the Great War could see them through communism’s teething troubles. Sorel’s mistake was to approach the business of statecraft from a theorist’s perspective. Composing an eloquent essay or a sharp rebuttal was far easier than dealing with overworked, incompetent bureaucracy and nebulous popular opinion. Sorel’s romanticised vision, incubated during years of study, of a worker’s paradise where human beings enacted his theories like actors giving life to a masterful script, was a pipe dream.

Louis Dubreuilh and his allies entered the vacuum. As career politicians, they knew how to translate vision into action. The problems, they said, ran deeper than just Réquisition révolutionnaire. Sorel’s mistake had been to enact full communism without building a proper government- Ludovic-Oscar Frossard compared it to building a pyramid upside down. The people needed to see a stable government rather than random and confusing policies.

Thus, the five regime heads crafted a new constitution in February 1919 behind closed doors; the masses in whose name the rulers wielded power had no say. Georges Sorel was in favour of looser rules and a more ‘revolutionary spirit’, but the SFIO men had a better understanding of how politics worked. Jean-Jacques Famride, not caring one way or the other, occasionally looked up from his novel to act as tiebreaker. Compromise was thus the order of the day. The SFIO and all labour organisations (many of which had survived for the past year despite Réquisition révolutionnaire’s prohibition) were replaced by the new Communist Party of France (CPF). Any Frenchman over the age of eighteen in good standing with the law- male or female, regardless of race- could apply. Georges Sorel was Chairman of the Party and Marcel Cachin #2. Elections to a unicameral People’s Parliament would be held annually. Although the constitution forbade other parties, multiple CPF candidates could run in the same province. Any adult citizen could vote, regardless of sex or property qualifications- radically broad suffrage compared to 1914. This, the Chairman declared, was socialist democracy.

Sorel took much flak for this. Disbanding the SFIO was seen as a power-grab; assuming control over the successor organisation calmed no one. Dubreuilh viewed this as a major intrusion on his power. The posts of prime minister and state president- official leader and second-in-command of the state- weren’t enough to soothe Dubreuilh or Frossard, respectively. The division of power between the state and Party- that is, between Dubreuilh and Sorel- would be a major sticking point throughout the regime’s. Barbs flew behind the scenes as blood rushed to the one-armed Sorel’s cheeks before Famride adjudicated.

Other matters were less controversial though. Banning non-Communist parties raised no ire, nor did repealing the worst excesses of Réquisition révolutionnaire- the Chairman was quite happy to let Dubreuilh handle unglamorous economics. 1919 saw revolutionary France’s centralised economy loosen. Some private enterprises returned and farmers began selling their produce again. Dubreuilh even went so far as to say that a socialist economy in the early stages should be like a caged bird, with individual effort (private enterprise) flying around freely within government-set parameters. (10) Of course, the Prime Minister hastily added, that was merely in the early stages. With time, French socialism would outgrow such measures. After all, their regime would last forever. History as dictated by Marx said so.

Flag of the People's Republic of France

* * *

Louis Marin didn’t want the Prime Ministership. Had Paul Deschanel not died in the Second Paris Commune (11), he would’ve remained contently shuffling papers. Yet, the world had other plans for him, and he found himself in Algiers. Marin privately compared himself to a minesweeper. “Both must stumble along, unaware of when their rendez-vous with fate will be but all too aware that it will come when they least expect it, and that every effort of theirs to survive will be rendered moot.” Or, as one of his aides put it, Monsieur Marin wanted to know if the governor had wired. A more apposite analogy would be a builder forced to make a house with only half the bricks required. Marin’s task in Algiers was to assess the wreckage which had drifted across the ocean and discern what needed rebuilding.

The situation now made the mess of six months ago look rosy.

Losing the mainland left only the pieds-noirs, French immigrants to the colonies, under la tricolour. Whites now found themselves massively outnumbered by Muslim Africans, foreigners in their own land. If there was a lesson there, Marin was too busy to notice it. That said, the pieds-noirs now found their ranks stiffened by an exodus. Aristocrats, Catholic priests, and conservatives all feared persecution. With the surrounding nations closing their borders, Algeria was the only place to go. One study conducted decades later estimated that these nouveaux pieds-noirs (as subsequent generations dubbed them) raised the percentage of whites in Algeria by three to five percent in the span of a few months. Smuggling refugees to Algeria became a major industry on the south coast, with up to seventeen thousand illegally crossing in 1918 and 1919. Regardless, Algeria, West Africa, Madagascar, and the French Caribbean were no substitute for Paris, the cathedral at Reims, the bustling docks of Marseilles, or the vast majority of French-speakers. Nevertheless, truth was on Marin’s side. The Third Republic was the internationally recognised government of France and had ruled by popular mandate for forty years. Not comprehending that the people had rejected him, Marin believed that if they saw him survive in exile they’d soon overthrow the “Sorel clique”. Thus, the Prime Minister wrote long essays on liberation and resistance which were smuggled into the mother country via Spain and Britain. However, as the summer of 1918 dragged on (his Gallic complexion suffered terribly in the desert), Marin realised his failure. The mainland regime would not crumble and he lacked the means to invade it. As much as it pained him, Marin privately conceded that results were fast transferring legitimacy from Algiers to Paris.

Having failed at statecraft, the Prime Minister opted to save his honour by falling on his sword. A few dissuaded him- what would the message be if the Third Republic’s government collapsed in this dark hour?- but most were glad to see him go. Louis Marin stepped down on 4 August 1918, and even today is remembered as one of the greatest buffoons in French history.

It’s difficult not to have a little sympathy for the man, as he’d inherited a hopeless situation from Paul Deschanel. Marin had taken over at the eleventh hour, with his predecessor dead and the people having set their heart on regime change. A swifter response to the Dijon uprising on Deschanel’s part, coupled with attempts at understanding its root causes, might have left the Third Republic in power and Marin as a nameless but content placeholder. But then, legitimate criticism of Deschanel has limits. Paul Deschanel had come into power because of the revolt caused by his predecessor’s incompetence. Emile Loubet might have been adequate in quieter times, but he was out of his depth in the postwar crisis. Had Loubet handled inflation and popular disgust, the Dijon revolt would never have erupted and Deschanel wouldn’t have faced such daunting prospects. Yet, though vituperating Loubet is reasonable, he inherited a hopeless task. The Treaty of Dresden had stripped France’s northeast and confiscated its specie, making hyperinflation certain regardless of what Loubet did. Marin’s failures, then, were just a fraction of what killed the Third Republic.

Proper procedure dictated an election. Parliamentary governments rose and fell (12), but parliamentary systems lived on. Yet, no one could pretend that this was normal. Paul Deschanel and then Louis Marin had ruled by emergency powers to prevent the loss of the mainland. Their failure deepened the emergency. With the departments under enemy rule, the people of France wouldn’t be able to vote, while many politicians either hadn’t escaped, or had defected to the revolutionaries; this included most of the Socialists. Thus, it was decided to craft a “crisis government” in back rooms to suspend the chaos of French politics until the mainland was freed.

Virtually all the emigres felt entitled to lead. They compared resumes in the Algiers town hall (converted into an impromptu parliament) while arguing bitterly. For the first three weeks of August 1918, the republic-in-exile lacked even the trappings of government. There was no one at the top to whom the world could point and say, “l’état, c’est lui!” Even in their darkest hour, myopic politicians saw only their own careers, only the glorious tales they could tell when they returned to France. Exile became half nuisance, half opportunity- yes, you were stuck in this bloody colony and your holiday was cancelled, but on the other hand half your political rivals were neutralised. It was enough to drive one man mad. Something, he decided, had to be done.

Georges Clemenceau conferred with Charles Lutaud, governor-general of Algeria, to plot treason equal to Sorel’s. Clemenceau believed in results above all else and had little respect for his fellow politicians. Their incompetence, he believed, had cost France the mainland, and he was damned if he’d let them bungle the redoubt. Clemenceau had no doubt about his own abilities, and believed that he was the only emigre with a chance of saving the country. One look at the deadlock told him that he’d never get anywhere through legal means. Lacking guns, Clemenceau realised that he needed outside help if he was to mount a coup. The governorship gave Charles Lutaud command of the colony’s militia… which just so happened to be the largest body of troops who answered to the Third Republic. Several quiet meetings throughout August produced a plan. Lutaud’s men would occupy the town-hall-cum-parliament and ‘suggest’ a definitive vote for a new government, at which point Clemenceau would present his credentials. It wasn’t treason, both men told themselves, it was patriotism. The Third Republic had to be rescued from its own leaders, and they loved France so much they’d do anything to save it.

Algiers awoke on 30 August 1918 to gunfire. The Republican Guards- bodyguards for the head of state- had received priority in evacuating the mainland specifically to resist a potential coup. Lutaud knew that trying to move them would arouse suspicions, which might lead to failure. As they had nothing to do with the Algerian colonial apparatus, the Guards didn’t answer to Lutaud. Thus, they had to be taken out. Lutaud had fed his men a steady wave of lies over the preceding days that the Republican Guards were plotting a coup of their own to place someone of their choosing in power. It was palpable nonsense, but after recent months nothing could surprise the cynical loyalists. Militiamen- white and native- attacked before dawn. The confused Republican Guards put a lot of lead in the air. These were all elite soldiers hand-picked for their loyalty to the regime, and protecting the government was what they’d been trained to do, but numbers were against them. It wasn’t the first time elan vital had failed to save the Third Republic. Civilians sheltered in their homes, unaware of what was happening- had the Sorelians tried to attack? Had the people risen up as in Paris or Dijon? Soldiers enacted a lockdown, proclaiming that there were ‘insurrectionists in our midst’. As many of these militiamen were Islamic Algerians, the locals trusted them and remained calm.

Meanwhile, the militiamen entered the town hall over the dead Republican Guards. There were no massacres, but the handful of people who tried to resist realised what a fatal mistake they’d made. Most threw up their hands and were marched to an ad hoc prison ‘for their own safety’, where they were placed under armed guard as gunfire rattled in the hallways. Republican Guards stationed in the town hall itself- as opposed to the barracks outside- fought hard. By now, it was eight AM, two hours after the initial gunfire. Governor Lutaud telephoned commanders across the colony, saying that “the attempted coup d’etat in Algiers is in the final stages of eradication… Dispatching additional forces would only invite unrest elsewhere.” In buying the lie, they unwittingly brought Lutaud time.

At 8:03 AM, armed militiamen burst into the main room where the politicians were hiding- the lock and bolt on the door were no match for a well-swung rifle butt. Some attempted to climb out of windows, others fell on their knees and clutched rosaries, others simply closed their eyes and waited to die. “Arretez!”, the militiamen cried. “Levez-vous vos mains!” Fifteen minutes later, Lutaud burst in breathlessly. He shed crocodile tears for the violence they’d suffered and explained that the Republican Guards had attempted to kill them all and seize power for themselves, but that the local militia had saved them. The fighting was over, Lutaud said, and it was time to return to the task of forming a government. Certainly, the recent chaos proved the need for a strong figure at the helm?

Georges Clemenceau chose that exact moment to walk in.

Georges Clemenceau and Charles Lutaud, photographed in different locations shortly after the coup

The moustached, bald Frenchman stared at his compatriots for a few moments, his eyes ablaze. “They have not taken me”, he cried, “but it was not for lack of trying!”

“It is high time we returned to voting”, interjected Lutaud, “now that the threat has passed.” He stood at the back. “I say we give Monsieur Clemenceau the time of day.” He nodded to his men, whose gleaming bayonets made the best argument of all for Clemenceau. The old man with the moustache smiled as three-fourths of those present voted to grant him power.

“Mistakes have been made; do not think of them except to rectify them. Alas, there have also been crimes, crimes against France which call for a prompt punishment. We promise you, we promise the country, that justice will be done according to the law. ... Weakness would be complicity. We will avoid weakness, as we will avoid violence. All the guilty before courts-martial. The soldier in the court-room, united with the soldier in battle. No more pacifist campaigns, no more Marxist intrigues. Neither treason, nor semi-treason: the war. Nothing but the war. Our armies will not be caught between fire from two sides. Justice will be done. The country will know that it is defended.” (13)

His first address set the tone for how Georges Clemenceau would rule. Liberating- the word ‘conquering’ angered him- the mainland was his one goal. To that end, he couldn’t tolerate dissent. The handful of Socialists who’d chosen to leave the mainland were all arrested- they’d belonged to the SFIO and were thus guilty by association of treason. Deschanel’s Emergency Powers Acts were renewed; striking was declared illegal since, as it had played a pivotal role in “la grande trahison” (14)- his term for the Revolution. If it could happen in Dijon and the Second Paris Commune, why couldn’t it happen in Algiers? Strict censorship was the norm- criticism of his regime or simply being left-of-centre became a crime as time wore on. Look what happened when Emile Loubet let leftists speak their minds. Though he concealed it for the first few weeks, when the truth that he’d seized power via coup emerged, Clemenceau was nonchalant. “Indeed I stole the Prime Ministership!”, he admitted in his later years. “This was not treason. The treason came from pacifists, politicians. Those who bickered as France failed, and were thus complicit in its demise.” Being Minister of War and Minister of the Interior simultaneously to Prime Minister gave Clemenceau control over all troops and security forces. Some saw him as France’s last great white hope, others saw a dictator who would share Deschanel’s fate. Admirers called him ‘the Tiger’, detractors mocked his moustache by calling him ‘the Walrus.’ Regardless of one’s opinion on him, no one denied that Georges Clemenceau was a force to be reckoned with.

Thus, as the 1920s emerged, the two Georges stared across open sights and open ocean.

Comments?

- OTL, about 1.4 million Frenchmen died in four years; here, since the war ends in 1916, it’d probably be just over half.

- He was briefly affiliated with Action Francaise and Integralism before the war

- Fictitious.

- Oxymoron in Aisle 4.

- Not plausible at all, inspired by this exchange.

- Reminds one of how we have not, in fact, always been at war with Eastasia.

- See chapter 20

- See chapter 40

- I just made 2,000,000,000,000 up. If that’s totally wrong, please say so! I’ve mentioned once or twice before that I’m not an economist….. No?

- Not my analogy; Zhao Ziyang came up with it in the Eighties. Much of what’s here is based off of my knowledge of Maoist China (the Communist regime about which I’m most knowledgeable), with hefty doses of War Communism in Réquisition révolutionnaire. If it’s too implausible, please say so and why!

- See chapter 43

- Living as I do in the United States, I continue to be baffled by the ease with which (from my perspective at least) parliamentary governments are elected and fall apart… but then, I’m sure the rigid four-year election cycle must seem peculiar when viewed from the outside. All what you’re used to, I suppose.

- An OTL quote, but with "Marxist" replacing "German"

- My many thanks to @Le Chasseur for catching this!

Last edited:

Chapter Forty-Five: Better To Bend Than to Break

"This state has, praise be to God, survived the Germans and their Italian and Austrian lackeys. But now we face a stronger enemy: ourselves. The war exposed our infirmities in the worst way possible: not just on the field of battle, but in the long soup lines and in the halls of power, and at the peace table in Konigsberg. We must adapt, modernise, revitalise ourselves if we are to survive."

-Tsar Michael II to Georgy Lvov, early 1917

"You, Your Excellency, remain the rightful Tsar. That brother of yours had no right to steal the throne from you, much less shut you up in here as though you were a cloistered woman in a convent! Following the passing of your son, you are the only man in this empire who loves Orthodoxy, Autocracy, and Nationality, and who is capable of fighting to restore them. Inertia now means that the mob of September will return..."

-Ivan Goremykin to the former Nicholas II

Mikhail Alexandrovich Romanov was Tsar of All the Russias, Supreme Autocrat by the Grace of God, lord and master over the world’s largest country. After Nicholas II bungled the Great War, Julius Martov had led Petrograd into revolt in September 1916 and Nicholas had ceded power to Michael in the hopes his brother could defeat the revolution. Martov’s alliance with Prince Georgi Lvov had nearly finished two centuries of Tsarism, and only Lvov’s defection had enabled Michael to retake the capital and make peace. The Treaty of Konigsberg, ending the war on the Eastern Front, had been surprisingly mild- Poland, the Baltics, and western Belarus were a comparatively small price for peace. Two months after the Tsarist crown had been knocked to the floor, the regime was secure, Nicholas was alive, the foreigners were no longer a threat, and Tsar Michael II enjoyed supreme power over more than 150 million Russians.

And the Tsar was none too happy about it.

Historians emphasise that the tsardom’s survival was a miracle. Tsar Nicholas, in the words of one modern Russian scholar,

"had taken the fruits of two hundred years of despotism and squandered them. In his myopia, shielded from the world by the golden window-panes of the Winter Palace, he saw only what the couriers wanted him to see, what his own regime’s propaganda told the proletariat. The loss of not just the Pacific Fleet, but the Baltic Fleet had made no impression on this man, nor the loss of hearts and minds. If he was, by the grace of God, tsar of all the Russias, then he operated under a charism of invincibility. The golden barrier separating him from the world was as fixed as a geometric axiom... In this cocoon, Tsar Nicholas was oblivious to the losses his empire was facing, to the slow but steady erosion of the supports… The armies of the Central Powers proved his undoing, as the cordite of Hindenburg and steel of Ludendorff proved unwilling to listen to the proclamations of God’s representative on earth…”

Michael was now forced to repair the damage.

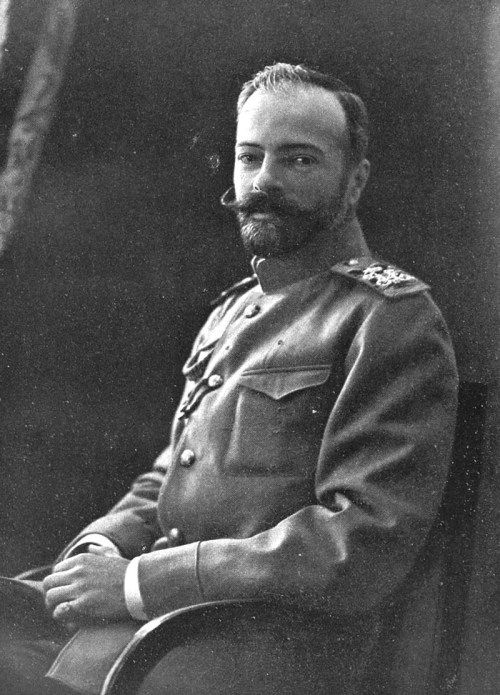

God's much-beleaguered representative on Earth, Tsar Michael II

Part of the reason the Germans had been comparatively lenient at Konigsberg was because they knew that Russia’s internal problems would distract it for years. The national economy was in shambles. During the war, the most manifest symptom had been soldiers going into battle unarmed, but civilians had suffered too. While it never reached the almost darkly comedic levels seen in France, inflation bit into the Russian worker’s pay and rendered savings useless. The queues for bread were always longer than the queues for bullets- and the demand didn’t vanish at the stroke of a pen. As the rest of Europe looked forward to their first proper meal in thirty months at Christmas 1916, the Russians were disappointed to find that rumours of extra potatoes in the shops were just rumours. The Central Powers were none too keen on selling to Petrograd while trade with neutrals resumed slowly. Farmers across Kazakhstan and the Volga were thus forced to work longer and harder to feed the Rodina.

Ukrainian unrest exacerbated Russia’s shortages.

Germany had refrained from taking Ukraine because it was too large to send their overextended forces into, but that didn’t mean Berlin wasn’t interested in exerting influence there. As soon as Michael’s regime sued for peace, revolt flared up in Ukraine. October 1916 saw blue and yellow fly in Kiev. “Give us a Hetman!”, they cried. “Free Ukraine in a free Russia!” Ukraine was not ‘southwest Russia’, it was a subjugated nation. Tsar Michael was known to be a liberal man and the nationalists hoped to reason with him. The protestors had disparate goals. Some wanted an independent Ukraine under a German prince, others hoped for a ‘Grand Duchy of Ukraine’ under Michael’s personal rule, a la Finland. Still others were Marxists who hoped for a socialist republic. Diversity proved the movement’s undoing because it impeded a united front. Tsar Michael couldn’t offer concessions so early in his regime because it would be seen as weakness. Poland, Lithuania, Belarus, and the United Baltic Duchy stood on German steel, while Finland had broken away under its own power. (1) These were tolerable because they were separate nationalities who’d always existed on the periphery of the empire. Ukraine was different- Petrograd dismissed it as “the southwestern provinces”, as Russian as Moscow or Siberia. If part of the heartland declared independence, the Tsarist balancing act would crumble.

It didn’t take long for Tsar Michael to overcome his liberal scruples.

Russia’s army may have been too weak to resist the Germans, but it had the strength to subdue Kiev. The protestors were driven from the streets and the Tsarist tricolour hoisted above Ukraine.

Unsuccessful though they were, the autumn 1916 protests convinced all Ukrainian people that they were a nation. The Tsarist bear who’d stood on them for centuries had had its claws trimmed by German steel; the new emperor appeared naked. If the Finns could achieve independence under their own power, they could too. Literature nurtured the independence movement. Mykhailo Hrushevsky, whose magnum opus History of Ukraine-Rus (2) made him a distinctly Ukrainian figure in the public eye, called for a second uprising from exile in Galicia. Nationalist poetry and literature circulated underground, as writers played cat-and-mouse with the secret police. Hrushevsky’s works were disguised as Bibles (3); people secretly studied the mother tongue. Austria-Hungary became a refuge for Ukrainians, as the war’s aftermath kept the Okhrana (4) out of Lemberg. Emperor Karl was sympathetic to the Galicians who slipped across the border to fight.

Had Ukraine erupted in 1917, it might have finished off Tsar Michael’s regime. As it was, the land remained under de facto martial law. Although governors and mayors officially ran the oblasts, cold hard steel kept the Ukrainians down. When the spring harvest came in 1917, peasants took enough for their families and hid the rest. Soldiers thus had to force peasants to work at gunpoint, which cost time, resources, and morale. The autumn harvest was no better.

Tsar Michael was torn. On the one hand, his liberal instincts told him to trade autonomy for cooperation. Grain was more valuable than pride. But as he watched the Croat crisis drive Hungary into revolt, the Tsar decided on conservatism. Compromise would validate the empire’s minorities, releasing forces outside his control; Russian chauvinism would keep the ship of state moving. So, the capital’s bread queues lengthened.

The empire’s Muslim minorities proved equally troublesome. More than one in ten imperial subjects prayed facing Mecca (5), and harboured a tradition of periodic rebellion. The war had taught them that the foreigners weren’t omnipotent, and many began dreaming of independence. The Ottoman sultan, whose status as Caliph gave him nominal suzerainty over all Muslims, was happy to encourage this. Russian influence in Persia had weakened, as the garrison moved to stem the feldgrau flood. Its border with Central Asia was long, while the Caucasus had plenty of ill-guarded passes which a knowledgeable man could slip through. Azeris and Uzbeks found plenty of nationalist literature wrapped around a rifle. Though the Uzbeks, Turkmens, Azeris, and Chechens were fatigued- conscription-related unrest which had flared up at the end of the war had been brutally suppressed- the most Tsar Michael could pray for was that the next round of violence didn’t come too soon.

His prayers would end up unanswered.

Ethnic Russians were no less of a headache. Tsar Michael believed a British-style constitutional monarchy where he’d share power with the Duma (parliament) to be the only way to prevent revolution. Reaction created a stiff structure which a strong breeze would break; reform created a flexible one. As the cornerstone of the system, Michael couldn’t suddenly abandon authoritarianism.Post-revolution Russian politics were so unstable that if Michael didn’t maintain a firm hand on the tiller, things would spiral out of control. Part of the problem was the Prime Minister. Prince Georgy Lvov was a longtime liberal who’d briefly aligned with Julius Martov in the September Revolution, but then repented and defected back to the Tsar in exchange for the Prime Ministership. This violated protocol, but Michael agreed. If he didn’t accept Lvov’s offer, he might not be able to rein the revolution in. Now, he was forced to pay the price.

Prime Minister Boris Sturmer, a Russian of Baltic German descent, was sacked in October 1916. Sturmer was outraged, and from then on was radically opposed to Michael and Lvov (though ironically, he was just as liberal as they were). Sturmer drifted to the right in the New Year, and made a famous speech in February attributing the loss of the Great War to a stab in the back from ‘subversive Martovists’. However, conservatives never embraced the former Prime Minister. His liberal past made his new rhetoric seem like political grandstanding, while the loss of his Baltic estates had rendered him bankrupt. Sturmer faded into irrelevance, and his assasination in July by a crazed nationalist (who referred to him as ‘the German Prime Minister’) attracted minimal attention.

Tsar Michael represented everything aristocrats had always feared- a weak-willed man who couldn’t stand up to liberalism. His failure to resist the ‘Martovist stab-in-the-back’ (virtually everyone on the right brought into this conspiracy), had reduced the empire to its smallest size in a hundred years. Michael’s opposition to Orthodoxy, Autocracy, and Nationality- the troika which the tsars had governed by for sixty years- menaced the status quo. “Before the war”, said one Russian conservative, “we feared outside forces eroding the power of the Tsar. But we were mistaken. The idea that the Tsar would erode that power of his own free will never crossed our minds!” To them, Lvov was a traitor (they remembered his affiliation with Martov), and Michael was a Trojan horse designed to give the reformers everything they wanted to lay the groundwork for the next attempt at revolution. It was nonsense, but when viewed from a reactionary perspective it made sense. To right-wing nobles- the one group who’d thrived before 1914 as Tsar Nicholas’ regime had catered to them in exchange for political support- Michael’s talk of reform was gravely offensive.

All this gave way to a conspiracy which convinced the Tsar he was under attack from his right as well as his left.

Nicholas II had survived the September Revolution. He and his family had fled the capital for Tsarskoe Selo, where he’d ceded the crown to his brother. As 1917 opened, Nicholas found himself shut out of power. Michael refused to let Nicholas return to Petrograd or live at Tsarskoe Selo for fear of popular anger. The former Tsar spent Christmas in Moscow before purchasing a lavish estate near Smolensk, where he slid into depression. Michael was taking the empire in an ominous direction, and he genuinely believed his brother’s life was in danger. Any moment, Nicholas told himself, revolution would return to the capital. If only he hadn’t abandoned the throne, the country wouldn’t be in this mess! Nicholas’ personal life offered no respite. His four daughters found their social circles and material wealth much diminished and their marriage prospects dead. Paranoia over assassins led Nicholas to forbid them from leaving the estate unescorted. They took their frustrations out on one another, and Nicholas rapidly grew sick of hearing their arguments. His wife Alexandra turned bitter, isolating herself in a separate bedroom where she wrote tortured letters to her friends. The real worry, though, was his son Alexei. The boy had been raised to believe that he’d be emperor one day, and believed that his ‘Uncle Michael’ had stolen the crown from him. Alexei grieved over the loss of most of his personal effects, having to leave the lavish Winter Palace for the relatively small estate, and the death of his healer Rasputin. (7) He gave vent to his depression and anger through rebellion, screaming at his relatives with a sharp tongue for a thirteen-year-old boy. Nicholas’ worry wasn’t over his son’s behaviour- Alexei had always been spoiled- but his health. With Rasputin dead, there was no one who could treat his son’s chronic hemophilia. If Alexei so much as nicked himself with a pencil, he might bleed to death. Nicholas didn’t see much of the boy because Alexandra kept him in her bedroom for days at a time, never letting him out of her sight for fear that he’d injure himself and even making him sleep in her bed. The former Tsar agonised over his son’s health and screamed at his wife to let him see his own boy, while Alexei pulled his mum’s sheets over his head and sobbed.

The inevitable happened on 18 April 1917. Alexei, in a troublesome mood that day, snuck into his father’s bedroom and stole several of his medals. The family butler yelled at him to give them back, but the boy ran to a second-floor window and threatened to throw them out. He lost his balance and tumbled to the paved road. He howled like a wolf in a trap as his sisters carried him inside. Alexei’s left wrist and nose were broken and one of his front teeth was chipped. Had he been alive, Rasputin would’ve healed the boy, but the finest doctors in Smolensk weren’t up to the task. Poor Alexei bled in bed for three hours. His skin turned pale, and by sunset he was chalky white. Alexandra and Nicholas stayed by his bedside all night as every trick in the doctor’s book failed. Shortly before midnight on 18 April 1917, Alexei Romanov died at fourteen years old.

Alexei’s death threw everyone into mourning black and bottomless depression. Alexandra remained in her room, fasting and praying with the door locked and curtains closed. A servant brought kasha on a plate once every eight hours, but she seldom had any appetite. Nicholas found solace in long horse rides along the perimeter of the estate, but also in that time-honoured Russian escape: the vodka bottle. In late-night rages fuelled by drink, he cursed “my fucking thief of a brother”, “traitors” (generally understood to mean anyone less reactionary than him), “my lying cousin Wilhelm”, “misery-guts” (Alexandra) and “that scamp Alexei”. (How the boy’s death was his own fault is an excellent question). He would pound on Alexandra’s door, demanding to talk to her, but the lock and bolt defied him. More than once, he went to Alexei’s bedroom and sobbed his eyes out, kicking the walls and cursing misfortune. His actions were indefensible, but he was acting from a dark place, trying to exhume a year of untrammelled pain. The former emperor’s eyes grew bleary and his stomach expanded. It’s a miracle that no one in the ‘family’ (if it could be called that) attempted suicide.

It was in this state that Nicholas received a special visitor.

Ivan Goremykin personified discontent with the current Michael-Lvov regime. Born to noblemen in 1839, he’d entered the civil service in his late twenties and spent the past half-century as a conservative firebrand. Goremykin believed Michael was verging on treason by refusing to play the part of God’s representative on earth, while Georgy Lvov was a traitor who’d lied his way into power. Needless to say, in Goremykin’s mind the Rodina had been stabbed in the back by Jewish Martovists.

Goremykin hoped to persuade Nicholas to return to power for the sake not just of Orthodoxy, Autocracy, and Nationality, but to save the empire’s soul.