You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Place In the Sun: What If Italy Joined the Central Powers? (1.0)

- Thread starter Kaiser Wilhelm the Tenth

- Start date

That depends on how much of a quagmire it turns into...I wonder if this war will strengthen or weaken American Isolationism.

Wow, Roosevelt? I'm hoping he gets a reality check, but the narration makes it sound like Super Special Awesome Teddy will win single handedly

I'm thinking it's more that they're gonna kill Teddy and that's gonna piss off the US, *hard*Wow, Roosevelt? I'm hoping he gets a reality check, but the narration makes it sound like Super Special Awesome Teddy will win single handedly

Wow, Roosevelt? I'm hoping he gets a reality check, but the narration makes it sound like Super Special Awesome Teddy will win single handedly

We shall see...I'm thinking it's more that they're gonna kill Teddy and that's gonna piss off the US, *hard*

bguy

Donor

Wow, Roosevelt? I'm hoping he gets a reality check, but the narration makes it sound like Super Special Awesome Teddy will win single handedly

What's the status of Alvaro Obregon? IOTL he broke with Carranza in 1917 but war with the United States might be enough to get him and Carranza to reconcile. If Carranza is willing to risk putting a popular political rival in charge of the army then Obregon was a pretty good defensive general (he whipped Pancho Villa at the Battle of Celaya) who could probably give TR a good fight.

Of course the real problem for the Mexicans is they are very quickly going to run out of ammunition. Mexico at this time lacked sufficient munitions factories to supply its own armies, and it is cut off from any foreign supplies with the US Navy blockading both coasts and a hostile Guatemala, so they aren't going to be able to sustain fighting at the level of intensity described in the last update for very long.

A lot of Villa's successes were due to having Felipe Angeles, who was a great military mind. He was absent at Celeya due to an injury, leaving Villa to just charge at Oregon's defenses over and over.What's the status of Alvaro Obregon? IOTL he broke with Carranza in 1917 but war with the United States might be enough to get him and Carranza to reconcile. If Carranza is willing to risk putting a popular political rival in charge of the army then Obregon was a pretty good defensive general (he whipped Pancho Villa at the Battle of Celaya) who could probably give TR a good fight.

Of course the real problem for the Mexicans is they are very quickly going to run out of ammunition. Mexico at this time lacked sufficient munitions factories to supply its own armies, and it is cut off from any foreign supplies with the US Navy blockading both coasts and a hostile Guatemala, so they aren't going to be able to sustain fighting at the level of intensity described in the last update for very long.

But Obregon is still a fantastic commander. Get him and Angeles together, and they can do a lot of damage to the US

I don't see Angeles siding with any government led by Carranza, even against a US invasion. Angeles is more likely to suck up to the Americans to get them to put him in charge of the new Mexico.A lot of Villa's successes were due to having Felipe Angeles, who was a great military mind. He was absent at Celeya due to an injury, leaving Villa to just charge at Oregon's defenses over and over.

But Obregon is still a fantastic commander. Get him and Angeles together, and they can do a lot of damage to the US

Obregon has allied himself with Carranza, yes. However, Carranza doesn't trust him to command large numbers of men in close proximity to the capital, so he's up in Sonora and Chihuahua.What's the status of Alvaro Obregon? IOTL he broke with Carranza in 1917 but war with the United States might be enough to get him and Carranza to reconcile. If Carranza is willing to risk putting a popular political rival in charge of the army then Obregon was a pretty good defensive general (he whipped Pancho Villa at the Battle of Celaya) who could probably give TR a good fight.

Of course the real problem for the Mexicans is they are very quickly going to run out of ammunition. Mexico at this time lacked sufficient munitions factories to supply its own armies, and it is cut off from any foreign supplies with the US Navy blockading both coasts and a hostile Guatemala, so they aren't going to be able to sustain fighting at the level of intensity described in the last update for very long.

And yes, Mexico is really fighting out of its weight.

Angeles has been in hiding in an undisclosed location since war broke out, but we'll hear more from him...I don't see Angeles siding with any government led by Carranza, even against a US invasion. Angeles is more likely to suck up to the Americans to get them to put him in charge of the new Mexico.

Him helping the US bully Mexico makes it a bit hard to really cheer for him.I really don't know why, but I hope this end terribly for Roosevelt.

He has been maybe my favourite American ever, but my first thought when I read his name was: " I hope he dies screaming".

He did a lot of bullying IOTL too. Big Stick.Him helping the US bully Mexico makes it a bit hard to really cheer for him.

Guatemala joined in willingly, not because it was coerced. Sure, it had its own agenda, but the US wasn't giving it marching orders.I love America's little Coalition of theUnwilling Bribed and CoercedWilling

I'm not surprised Teddy Roosevelt mobilized some forces.

Cuba, Haiti, and the Dominican Republic didn't have much choice, thoughGuatemala joined in willingly, not because it was coerced. Sure, it had its own agenda, but the US wasn't giving it marching orders.

I'm not surprised Teddy Roosevelt mobilized some forces.

Hence why I said 'bribed' as well.Guatemala joined in willingly, not because it was coerced. Sure, it had its own agenda, but the US wasn't giving it marching orders.

I'm not surprised Teddy Roosevelt mobilized some forces.

Update tonight- we're back to Danubia.

After that, we'll cover Mexico City, then we need to give the French their due!

I think this upcoming chapter deserves a little forward. It centres around Karl of Austria and the fall of Vienna.

This chapter has a certain degree of personal significance for me, moreso than any of the other Place In the Sun chapters. IRL, Karl is my patron Blessed (he was beatified in 2004) and I was excited to be able to incorporate him into the TL. This fact was paramount in my mind as I wrote this chapter (alongside the desire for a dramatic fall of Vienna!). Thus, just bear in mind that certain aspects of the chapter have a certain personal significance to me as you read, comment, and hopefully enjoy. I understand that some parts of it won't be in accordance with what everyone believes and I would respectfully ask that if that's so, you refrain from mentioning that fact.

Once again, I'd like to thank everyone for their continued interest in Place In the Sun- it's my baby and I've put so much effort and work into it over the past three months and I couldn't have done it without you.

So I'll see you in a few for the update.

Now back to our regularly scheduled programming...

After that, we'll cover Mexico City, then we need to give the French their due!

I think this upcoming chapter deserves a little forward. It centres around Karl of Austria and the fall of Vienna.

This chapter has a certain degree of personal significance for me, moreso than any of the other Place In the Sun chapters. IRL, Karl is my patron Blessed (he was beatified in 2004) and I was excited to be able to incorporate him into the TL. This fact was paramount in my mind as I wrote this chapter (alongside the desire for a dramatic fall of Vienna!). Thus, just bear in mind that certain aspects of the chapter have a certain personal significance to me as you read, comment, and hopefully enjoy. I understand that some parts of it won't be in accordance with what everyone believes and I would respectfully ask that if that's so, you refrain from mentioning that fact.

Once again, I'd like to thank everyone for their continued interest in Place In the Sun- it's my baby and I've put so much effort and work into it over the past three months and I couldn't have done it without you.

So I'll see you in a few for the update.

Now back to our regularly scheduled programming...

Last edited:

bguy

Donor

I think this upcoming chapter deserves a little forward. It centres around Karl of Austria and the fall of Vienna.

This chapter has a certain degree of personal significance for me, moreso than any of the other Place In the Sun chapters. IRL, Karl is my patron Blessed (he was beatified in 2004) and I was excited to be able to incorporate him into the TL. This fact was paramount in my mind as I wrote this chapter (alongside the desire for a dramatic fall of Vienna!)

If you're a fan of Karl then did you ever happen to read Mike Stone's timeline back on the old soc.history.what-if newsgroup "Mr. Hughes goes to War"? It's a good read and Karl is featured pretty heavily in it.

If you're a fan of Karl then did you ever happen to read Mike Stone's timeline back on the old soc.history.what-if newsgroup "Mr. Hughes goes to War"? It's a good read and Karl is featured pretty heavily in it.

Ooh, will do! Thanks for sharing that.

Chapter 20- The Fall of Vienna

Chapter Twenty- The Fall of Vienna

"I know my people well- I have lived amongst them my whole life. They will hold through anything, make no mistake of that. They will hold."

-Emperor Karl to his wife, 29 October 1917

"The old man is dead, eh? And he left a five year-old boy to play with his crown in Salzburg? What news- we shall be entertaining the ambassador from England three days from today!"

- Mihaly Karolyi, November 2 1917, upon hearing of Karl's presumed death

The Hungarians had done better than anyone anticipated. When nationalist pride prompted Prime Minister Mihaly Karolyi to declare the independence of the Hungarian Republic on 13 July, 1917, few had given the Hungarian state long to live. On paper, the deck was hopelessly stacked against it; the Habsburg empire surrounded it on all sides, while the Central Powers were hostile towards the revolt. When Emperor Karl I had ordered Franz Conrad von Hotzendorf to mount an offensive south from Slovakia, everyone had expected that the imperial bull would batter down the gates and waltz into Budapest. Yet… that didn’t happen. The Hungarians out-thought General Conrad and ended up losing only a few small villages. This cost Conrad his career; Emperor Karl sacked him and replaced him with General Arthur Arz von Strassenburg. Von Strassenburg was, however, an unknown quantity both to his side and the enemy. He had not especially distinguished himself in the Great War, but neither did he have any great blunders on his record. Only time would tell.

Prime Minister Karolyi should have been happy. His men had turned the Imperial forces back; the enemy armies were still well north of the Danube and in no position to break through any time soon. The recent fighting had cost them far more than the Hungarian defenders. To the south and east, meanwhile, the enemy forces coming from Croatia and Transylvania were stalling. The rebel army’s supply of munitions and equipment was still reasonably high, and best of all, neither Germany nor Italy looked to be interested in intervention . In short, the war was going well.

What, then, was the issue?

Karolyi's knowledge of American history was minimal. As a European, he seldom gave thought to Charles Evans Hughes’ republic. Yet, in the weeks leading up to Hungary’s secession, he had got his hands on a history of the American Civil War. His position, he believed, was analogous to the Confederacy’s in the first months of that war. His state held a temporary initiative, but that would not last. Conrad’s past offensive had, despite its failure, captured a certain amount of territory. If that happened time and time again, the defenders would tire and give way. Like the American South facing off against the Union, the rebel Hungarian state couldn’t hope to win a war composed of toe-to-toe defensive battles; the ever-growing strength of Danubia would eventually wipe the state out.

Hungary had to teach the empire that rebels could fight back, and that it was better to let Karoly’s state go rather than expend all that blood and treasure- before it was too late. And to do that, the Hungarians needed to take the offensive.

If the Hungarians launched a major offensive, they could persuade the Danubians to give up the war, but only if they did it properly. A lightning strike would be necessary against a major target; the shock factor of realising how dangerous the Hungarians could be would then persuade Emperor Karl to give up. To continue with the American Civil War analogy brewing in Karolyi's mind, the Confederacy in 1862 had lunged into Maryland and Pennsylvania, hoping that capturing Baltimore or Philadelphia would terrify the Union into letting them go. While General Lee’s manoeuvre had failed, Karolyi told himself, that was due to tactical issues unrelated to the present conflict; the grand strategic aspect was what counted. And there was one glaringly obvious target to strike at: Vienna.

No one in the imperial capital imagined that the war would come to them. After all, the posh gentlemen scoffed, these rebels were just jumped up Slavic provincials who didn’t know one end of a wineglass from the other! When the news of Hungarian secession reached the capital, the general reaction had been that Conrad would be in Budapest before the onset of winter. As Empress Zita wrote in her diary shortly after the outbreak in hostilities, “Looking around, I do see soldiers on the streets, it is true, but this is what one would expect from a capital city. People still merrily go about their business, enjoying their lives, selling paintings, drinking wine. In short, one could not prove by the spectacle meeting one’s eyes that the empire is at war.” After the first imperial offensive of the war flopped, the people still scoffed. Yes, some petty frontier towns might change hands, but never Vienna. The city was too ancient and too grand for war to pay a call here. After all, in the Great War against the Russian titan, had the capital ever heard so much as a single cannon going off?

They were soon to get an awakening.

The distance from the Hungarian border to Vienna was only thirty kilometres at its closest point. Compounding the situation, the Danubians had put minimal effort into fortifying these approaches. Of course, this wasn’t really their fault as no one had predicted the Hungarian revolt, let alone the fact that said rebels would try to take Vienna. However, the defenders had one major advantage. The westernmost part of Hungary, closest to Vienna, was known as the Burgenland. It was inhabited predominately by Austrians, whose loyalty lay firmly with Emperor Karl, and whose opinion of Mihaly Karolyi wasn’t fit to repeat in a civilised setting. Yet, although less than a tenth of the population was Hungarian, they held disproportionate influence within the territory and it had always come under Budapest’s sway. Fighting had broken out in the territory even before the formal declaration of Hungarian secession, as individual Austrian “patriots” took it upon themselves to prevent the local Hungarians from rising. The town militias, many of whom were composed of ethnic Magyars, intervened on the side of their countrymen, leading to brutal street fighting which left many dead. The Hungarian Republic’s declaration of independence only led to an escalation of the violence. Caught in the middle was the area’s significant Croatian population, who- their homeland having spent far too long under Budapest’s yoke- sided with the Austrians. Since mid-July, the Hungarians in the region had been sitting atop a bomb primed to go off, fearful that an imperial march east would meet with sympathy from the locals.

Using the Burgenland as a base for an assault on Vienna was going to be a devil of a job.

General von Nadas was summoned to Budapest on 10 October and given his new assignment. There were approximately a million and a half soldiers fighting for Hungary; only a few more were on the way. Since the empire surrounded Hungary, slightly under a million of those men were needed to man the frontiers, leaving 600,000 soldiers free for operations elsewhere. (1) Károly made it clear to his commander that these men were the cream of the crop and that they couldn’t be replaced if things went wrong- so his head would be on a platter if this operation failed. With that ringing endorsement in his ears, von Nadas received orders to muster the listed units in the Burgenland and march on the imperial capital as soon as possible. The Hungarian Third Army, as the Hungarian high-ups christened it, moved west. It was obvious to the men where they were headed, and they rapidly began calling themselves “Karoly’s Avengers”, and the “Army of the Schonbrunn”- the latter a reference to the Habsburg palace in Vienna. For security reasons, officers made every attempt to suppress such nicknames, but they survived and postwar chroniclers often use these terms.

Unsurprisingly, the first shots fired by the Third Army were in the Burgenland. The locals were none too pleased to see 400,000 Hungarians- another 200,000 remained behind as a last-ditch reserve- arriving in their territory in the last weeks of October, just as the last of the harvest was being brought in, and made their displeasure felt. Minor incidents took place- Hungarian horses vanished in the night, ground glass somehow got mixed in with the biscuits the soldiers carried for field rations… charming things like that. The Hungarians reacted savagely, taking and executing hostages… which only made the Austrians and the Croats love them still more. Considering that this was to be the forward base for the push on Vienna, they couldn’t tolerate an active movement of francs-tireurs , and they peeled an additional three thousand men off for anti-partisan duty. This would keep the Burgenland quiet for the rest of the war, but it would come at a cost of combat effectiveness. Meanwhile, the concentration of force so near the capital had terrified the Danubians. Emperor Karl was not naive, but neither was he a military man. He had very much left the war to first Conrad then Straussenburg, and neither had suggested that the Hungarians could move against the imperial capital- thus, he was horrifically surprised when his commanders told him what was going on. Since much of Danubia’s prewar rail network ran through Hungary, transferring forces from Galicia or the Balkans would prove a daunting task. The empire didn’t have much left in Austria or Bohemia; most of those units were away at the front. Pulling units out of western Austria was possible, but Karl was reluctant to do it barring a dire emergency; he feared that if Danubia appeared to be coming apart, the Italians might attempt to grab some of the land in the region they’d coveted for years. It would all come down to whether or not the defences on the border would hold…

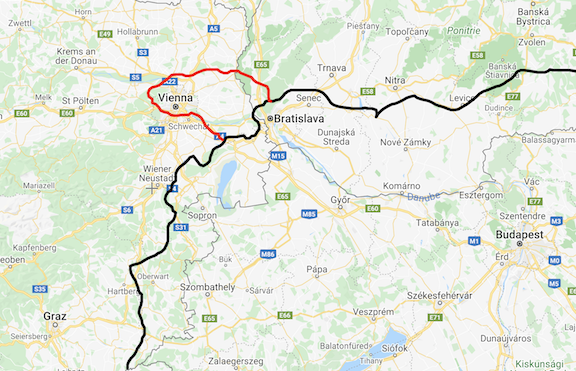

A (badly made) map roughly showing the front lines at the beginning and end of the chapter...

The Hungarian offensive opened on 27 October with a massive barrage of the imperial trenches. Contrary to General von Straussenburg’s predictions, the Hungarian assault came on a narrow front. The Danubians had anticipated that the rebels would try to capture as much of the Austrian heartland as possible; instead, von Nadas appeared to be focussing all his energies upon Vienna. Almost half a million Hungarians went over the top on 27 October; despite Great War-style defences, the imperial troops weren’t up to scratch. By midday, sheer force of weight had displaced the defenders from their frontline trenches, leaving imperial captains and majors frantically screaming into the telephone for reinforcements. It did them little good, and by the end of the day the frontline villages of Sommerrein, Sarasdorf, and Bruck an der Leitha lay under Hungarian occupation. Fighting died down during the night, but the next day found the Imperial troops no more able to halt the rebel tide. By noon on 28 October, all but a few pockets of defenders had thrown up their hands and consigned themselves to captivity. With a great war-cry, the Army of Schonbrunn poured through the gap thus created in pursuit of its namesake. Village after village fell into Hungarian hands, and by the end of the day the rebels had advanced five miles- results which many a Great War soldier would, quite literally, have died to achieve. It was the old magic word: breakthrough.

In Vienna, Emperor Karl was in a state close to panic. They had shattered the frontline defences in a day, and by the end of the day the Schonbrunn Palace was but fifteen miles from the fighting- the rumble of guns was quite audible as the emperor ate his supper. There was nothing for it- Vienna could not be held. Straussenburg could concentrate no amount of men in time to halt the Hungarian advance east of the city. If the enemy maintained his current pace, von Strassenburg told his sovereign, he would be here in three days. Anarchy was rife in the city, with refugees clogging up the westward roads which the troops heading east needed. Those determined to stick out Hungarian occupation- even those who were normally very peaceful and law-abiding- often turned to crime to get their hands on some tinned food or emergency cash. People buried their valuables in back gardens and bolted the doors in case of trouble. The fire brigade were occupied putting out blazes set by looters or by refugees determined not to leave anything for the Hungarians. After the police failed to establish order; the mayor declared martial law at one PM on the 28th. A veneer of panic lay just beneath one of Europe’s oldest cities.

That night, with everything around him collapsing, the emperor went to the Cathedral of Saint Stephen, where he knelt in prayer for four hours, until midnight. He knew that he couldn’t hope to hold the capital, but he prayed that he might minimise the sufferings of his people and keep the empire together. No doubt, Karl wept a few private tears in the pew that night. He returned to the cathedral the next day for Mass, and for an hour the war faded away. Under the familiar arched ceiling, with the beautiful icons and the glorious tabernacle in front of him, and the Eucharist on his tongue, Emperor Karl received the great gift of peace. After the service, he visited Cardinal Friedrich Gustav Piffl in his office, and told him that if he wished to flee the capital- for the sound of artillery had already interrupted the chants at Mass- no one would think any less of him. Cardinal Piffl smiled and shook his head. The people of Vienna needed their shepherd now more than ever. If he fled, deserting his post, what kind of example would he be setting? His responsibility to the people of the Archdiocese of Vienna wouldn’t change regardless of whose flag flew in the city. Cardinal Piffl then summoned one of the capital’s most promising priests, Father Theodor Innitzer. (2) The two men charged a presumably somewhat overawed Father Innitzer with accompanying any refugees from the city and tending to their spiritual needs. He collected his vestments and missal, and took everything he needed for the Eucharistic celebration before heading out to join the columns of refugees fleeing westwards. Servants buried the cathedral’s fine relics and art, and Emperor Karl returned to the Schonbrunn Palace.

A modern picture of Saint Stephen's in Vienna. The church was very heavily damaged in the capture of Vienna, but painstakingly rebuilt afterwards and is nearly indistinguishable from the prewar version.

29 October was a rotten day at the front. Von Straussenburg was paying the price for his hubristic belief that the Hungarians couldn’t strike west; he had nowhere near enough men to repulse the foe. Enemy troops crossed the Danube and advanced up both banks, seizing pleasant hamlets who hadn’t heard the sounds of fighting since Napoleon’s day and ruining their tranquility. Local militias- the Landwehr- did their utmost to resist, but when fifty greying veterans of the Austro-Prussian War came across nearly four hundred thousand modern troops, the outcome was never in doubt. The Danubian forces never possessed enough strength in one place to set up a firm, entrenched redoubt, and so they had to keep retreating. Imperial commanders fought a series of delaying actions, trading space and men for time. A company might entrench, fight for half an hour to keep Fischamend under the imperial flag for a few more minutes, and then retreat to play the dynamic out again in Flughafen Wein an hour later. Few had much to eat or many chances to rest as death lay waiting in the cool autumn breeze. When the sun slipped below the mountains, Hungarian troops found themselves in the Vienna suburb of Schwechat. They had not quite succeeded in taking the capital in two days- but there could be no doubt in anyone’s mind that 30 October would be the great day. That night, Hungarian artillery indiscriminately shelled Vienna, seeking to disrupt the movement of troops and terrorise the population. “Tomorrow”, General von Nadas boasted in his diary, “1848 shall be avenged!”

Refugees poured out of the city throughout the night with little more than the clothes on their backs. They screamed and argued, made a fuss, and impeded the passing of troops towards the city. (3) Those who had decided to stay fled to basements and attics, trying, usually with little success, to get a wink of sleep. The garrison keeping the city under martial law had entrenched itself on the perimeter, joined by the police and local Landwehr- this had the unintended side effect of giving looters and burglars a free hand. The few remaining servants in the Schonbrunn Palace buried the imperial crown jewels and other historic artifacts deep underground before joining their wives and children. And in the imperial bedchambers a little before midnight, a very important farewell was said.

Emperor Karl would not abandon the city. Touched by Cardinal Piffl’s heroism, he had decided to stay on in Vienna. Just as Constantine XI had remained in Constantinople to the bitter end half a millenium ago (4), so he would stick with his people. Empress Zita- who, unbeknownst to anyone at the time, was pregnant (5)- and their four children were instructed to flee westwards with Karl’s brother, Archduke Maximilian. Sitting his eldest son Otto on the knee, Karl told him that he would be an emperor one day, and that his mum and Uncle Maximilian would help him. He kissed Zita goodbye one last time and promised that “we will see each other again. God willing, it will be in a few months, after the war. But if He should wish otherwise, we will meet in a different life. Help the children get to heaven, and do not let them forget me.” He handed her a rolled-up piece of paper and told her not to read it until word came that Vienna was gone. An armoured lorry took the Imperial family to Salzburg, while the emperor went down to Saint Stephen’s one last time. The church was locked and bolted for obvious reasons, but Cardinal Piffl sent a servant to open it for the emperor. Karl requested Holy Communion one last time, and spent the night in prayer for his family, his people, and his empire.

At five AM, the roar of an artillery barrage announced that the Hungarians were en route. The invaders climbed out of their trenches for the last time and took on the rearguard defending Vienna. As expected, the defenders put everything they had into this last fight, but it wasn’t enough and by seven AM the rebels were entering the capital. Determined not to let his beloved city be sacked, Karl sent word to the commandant that Vienna was to be declared an open city. Far better it be captured intact with minimal loss of life and destruction of property than the foe destroy it.

Letting the Hungarians in peacefully didn’t entirely save Vienna. Conquering armies have never been kind to cities, and once the Hungarians reached their goal they took whatever they could carry. They stole fine clothes and watches, stuffed gold and silver into pockets, and pillaged the finest restaurants. Men were shot down in the streets and women taken by force. The emperor heard all this from inside the cathedral, and he wept, murmuring over and over, “Father, forgive them- they do not know what they do.” (6) At eight AM, as though it were an ordinary day, Cardinal Piffl came out and went into the confessional; the emperor followed suit. They came out a few minutes later and Piffl offered Mass; the emperor was obviously the only one in the congregation. It was a strange spectacle, with the Holy Sacrifice being offered with gunfire and screaming in the background in lieu of angelic chanting, but it was still Mass. Sadly, it was never to be finished. Halfway through, a ferocious banging came on the doors, followed by a gunshot; the lock had been shot off. A handful of Hungarian troops- evidently not Catholic like most of their countrymen- burst in and paid very little attention to the sanctity of the church, or to the one man in the pews. In an iconic scene, both emperor and cardinal ignored the looters, keeping their eyes fixed on the Mass. Icons were carted off to meet a fate they didn’t deserve, and men grinned at the prospect of getting rich. One of the Hungarians grabbed his pistol and made for Cardinal Piffl. The cardinal turned around a split second before the murder. Grinning, the Hungarian marched over the corpse, up the altar. This was something Karl could not stand. As the Hungarian soldier reached for the tabernacle, Karl tackled him to the ground; one of the soldier’s comrades shot the emperor dead. Karl von Habsburg was only twenty-nine years old, and had ruled the United Empire of the Danube for less than a year.

A moment later, the church caught fire. Of course, this was not especially surprising in and of itself- with Vienna being looted, a fire was expected. Within moments, the inferno had trapped the offending Hungarian soldiers. The fire wore itself out quickly, leaving nothing but a pile of ashes on the floor. The altar and front of the cathedral were seriously damaged, and would not be fully reconstructed until 1922- the front of Saint Stephen’s has survived undamaged ever since. However, two items escaped the blaze. The first of these was not discovered until after the war, when Cardinal Piffl’s successor was walking around church grounds during the reconstruction, and stumbled across a singed box. He opened it to find several perfectly preserved Hosts. These Hosts were carefully placed inside a special container and have survived perfectly to the present day. The second item to escape the blaze was a statue of the Virgin Mary- it remained on its plinth during the fire and was left without so much as a singe mark on it. However, when Hungarian troops- fortunately, less inclined to vandalism than the ones mentioned above- discovered the statue, its face was wet. The Twin Viennese Miracles remain well-documented and well-celebrated within the Catholic Church even today. Since he had died to protect the tabernacle from vandalism, he was declared a martyr by Pope Benedict XV a year later, and was canonised in 2017- 30 October became his feast day. (7)

An icon of Saint Karl of Austria (1888-1917) the Emperor of Peace, the Host-Saver.

Following the capture of Vienna, the Hungarian Third Army stopped to rest. Garrisoning the city, even with much of its population having fled, would be a monumental task. Fighting had damaged much of the city- although it wasn’t as bad as some had feared- and analysing what still stood and what to do with what would be a time-consuming process. There was also the monumental question of the imperial family- captured servants revealed that everyone but Karl had fled to Salzburg, but they had no idea where Karl himself was. This prompted a massive search lasting ten days. Finally, it was concluded that he was dead. Naturally, Prime Minister Karoly trumpeted this to the world. The Emperor was dead- who would lead Danubia now? Hungarian arms had proven themselves time and again; with Vienna lost and the Emperor dead, why couldn’t they see that they had lost the war, and that Hungarian arms had forged a real nation? Diplomatic recognition for Hungary was surely imminent, Karoly told himself…

The Imperial family reached Salzburg two days later. Poor Empress Zita wept the whole way, convinced that her husband was dead, while her brother-in-law and her sons tried to console her. As soon as they reached their new home, a breathless messenger rushed up to them with the news that the capital had fallen four days earlier. Zita took the letter out of her pocket and, hands shaking, opened it. Inside, her deceased husband had written:

My dearest,

By the time you read this, I shall be dead.

I am torn writing this, my dear. I have a great duty to you, my wife, and to my children. Yet, I have a duty to my people and to my empire as well. Never have my responsibilities clashed so in all my days. Making this choice pains me, my dear, but I must stay with my people. They need me in their hour of weakness. I know that you will do everything within your power to raise our children as I would have wanted them raised, and that you and my brother Maximilian will raise our son Otto to follow me one day. I ask that you pray for my soul, and may we see each other in the Kingdom of Heaven before too long. I love you.

There followed a ludicrously long signature listing his several dozen titles- second of which was “King of Hungary”. The Archbishop of Salzburg was summoned, and a weeping five-year-old Otto was crowned with all of his late father’s titles, making him the sixty-third Habsburg ruler of Austria since the late thirteenth century, and the second sovereign of the United Empire of the Danube. Of course, since he was still in short trousers, Maximilian was crowned as Regent until Otto turned eighteen. That same day, he ordered General von Straussenburg to send whatever he could, from wherever he could get it, to ensure that the Hungarians couldn’t pour west into the imperial heartland. Meanwhile, he had a train to catch for Berlin...

- Very, very rough calculations have given me just shy of two million Hungarian troops for the whole war; I figure that peeling off 600,000 for something as massively important as taking Vienna is possible.

- OTL’s Archbishop of Vienna from 1932-1955.

- I agree, it doesn’t make military sense to try and defend Vienna in the wake of overwhelming odds- but from General Arthur Arz von Straussenburg’s perspective, the capital is far too important politically for him to say he let it go without a good fight. This will condemn a lot of Danubians to avoidable deaths, but TTL’s characters are human- they make mistakes too!

- The inspiration for this idea, at least partially.

- Pregnant with Archduke Carl Ludwig. Since he was born in March 1918, he would still have been conceived ITTL. I know there’s a long argument about whether or not people should be born post-POD, but I’m going to let him be born. Besides, he’s not an important person in the TL- odds are we’ll never hear from him again.

- Luke 23:34, incidentally.

- Karl was beatified in 2004 IOTL- I can’t remember his feast day off the top of the head.

Last edited:

Share: