I don't think you need to develop new religions or something like that. I just thought that if you gave a name to a famous conqueror and empire builder that you could also have major philosophers appear that could show the development of thought. I don't think you need to add this as what you have done is interesting and entertaining to read, only if you want to add more content to the timeline of course.Axial age-like religions? You know, I don't really know. I'm thinking about it, but at this point I'm not really too sure. There's definitely factors that could create more demand for such a religion, but it's another for these religions to actually appear. It is an area rich in inspiration, though.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Pecari rex, Equus regina: American Domesticates 3.0

- Thread starter twovultures

- Start date

twovultures

Donor

Journey from the West

A long time ago, people lived in a land on the far edge of the west, where the sun touched the horizon and walked among humans every day.

One day, the sun saw a beautiful maiden named Sum-Ka-Way. He fell deeply in love with her, and married her. Although he could only be with her for a few minutes each day before he went into the underworld to journey back to the eastern horizon, their marriage was loving and produced a son who she named Uyot. Uyot grew up tall, strong, brave, and just.

During this time there lived a man named Took-Moosh-Woot who was a bully. He enjoyed tormenting those smaller and weaker than himself, and took to tormenting the harmless Rattlesnake. One day Rattlesnake had enough, and went to Uyot to ask for help. Uyot broke off two sticks, and gave them to the Rattlesnake so it could defend itself. The rattlesnake hid the sticks in its mouth, and waited for Took-Moosh-Woot to return to bully him. When Took-Moosh-Woot came to him, Rattlesnake bit his finger off, which can still be seen in the sky [1].

As Took-Moosh-Woot lay dying from Rattlesnake’s venom, he gathered his family together and told them to burn his body. Now at this time, Coyote lived among people. When he heard that Took-Moosh-Woot was dying, he decided that he would eat the corpse. He boasted of his intention, and so Uyot gathered Took-Moosh-Woot’s relatives and told them to burn his body so that Coyote would not eat it. When Took-Moosh-Woot finally died, his family built a pyre and placed his body on it, and then stood around the body to stand guard. But, one by one, his family grew tired.

“Let us sleep” they said. “If we surround the fire, Coyote will not be able to reach the body without waking us up.” And so they all lay around the fire and slept. Coyote saw this, and as soon as they all fell asleep, he ran as fast as he could toward the fire and leapt over the bodies. He landed in the pyre, and devoured Took-Moosh-Woot’s body.

Seeing that the people had failed to protect one of their own, the sun grew angry and abandoned the sky. In his wake, the skies grew dark and began to fill with heavy storm clouds. Seeing this, Uyot gathered the people together and told them to build boats, because a storm was coming. Soon, a great rain began to pour down, and the wind began to rage. The people got into their boats, and soon a flood came and lifted them up. The people sang their sacred songs so they could hear each other over the storm and keep their boats together. Some people did not sing the sacred songs properly, and trailed behind the main fleet. They would be the foreigners. Others did not memorize the sacred songs at all, and were swept away in the flood to the distant edges of the world, where they would become the Kastyanos [2] and the Oona [3].

Eventually, the flood waters receded and the people landed in the valley of the Ataaxpaala (OTL: Mississippi River). They were now safe, but the sun still refused to shine. Uyot saw this, and declared “now that one of us has died, all of us must die. Took-Moosh-Woot will take us all with him. From now on, all humans must die.” Saying this he himself lay down on his deathbed and prepared to pass on.

Before he died, he prophesied that a great fire would develop in the east. He summoned Coyote, and told him to go east to fetch the fire for his funeral pyre. Coyote followed his instructions, and went east. There, he saw a great fire on the horizon, and ran after it. He chased it, but the more he ran towards it the further away it seemed.

Meanwhile, Uyot died. His family gathered his wood for his body, and burnt it. From far away, Coyote saw the fire and turned to run towards it. As he got closer, Uyot’s family saw him coming and surrounded the fire, but Coyote kept running towards it. They feared that Coyote would leap over their heads, so fast and hard he was running, so they sent the strongest of their number to drag over the boats they had used to float over the floodwaters. The people then stood on the boats, and sang their sacred songs once again, beseeching the boats to carry them to Coyote so they could fight him. The boats transformed into horses, and the family rode against Coyote, chasing him away forevermore.

Glimpsing their brave actions from over the horizon where he had been distracting Coyote from his son’s funeral, the sun rose into the sky once again, shining on the brave sun-born, who had now claimed their place as the leaders of the people, while Took-Moosh-Woot’s people were relegated to be workers of the earth and hewers of wood. Uyot rose again to follow his father across the sky as the moon, giving the world light even when there was no sun.

[1] Referring to a constellation of stars around the North Star, this appears like a hand with an amputated finger.

[2] Whites

[3] Blacks

This story was based on myths I read here and here, which I found through www.native-languages.org

A long time ago, people lived in a land on the far edge of the west, where the sun touched the horizon and walked among humans every day.

One day, the sun saw a beautiful maiden named Sum-Ka-Way. He fell deeply in love with her, and married her. Although he could only be with her for a few minutes each day before he went into the underworld to journey back to the eastern horizon, their marriage was loving and produced a son who she named Uyot. Uyot grew up tall, strong, brave, and just.

During this time there lived a man named Took-Moosh-Woot who was a bully. He enjoyed tormenting those smaller and weaker than himself, and took to tormenting the harmless Rattlesnake. One day Rattlesnake had enough, and went to Uyot to ask for help. Uyot broke off two sticks, and gave them to the Rattlesnake so it could defend itself. The rattlesnake hid the sticks in its mouth, and waited for Took-Moosh-Woot to return to bully him. When Took-Moosh-Woot came to him, Rattlesnake bit his finger off, which can still be seen in the sky [1].

As Took-Moosh-Woot lay dying from Rattlesnake’s venom, he gathered his family together and told them to burn his body. Now at this time, Coyote lived among people. When he heard that Took-Moosh-Woot was dying, he decided that he would eat the corpse. He boasted of his intention, and so Uyot gathered Took-Moosh-Woot’s relatives and told them to burn his body so that Coyote would not eat it. When Took-Moosh-Woot finally died, his family built a pyre and placed his body on it, and then stood around the body to stand guard. But, one by one, his family grew tired.

“Let us sleep” they said. “If we surround the fire, Coyote will not be able to reach the body without waking us up.” And so they all lay around the fire and slept. Coyote saw this, and as soon as they all fell asleep, he ran as fast as he could toward the fire and leapt over the bodies. He landed in the pyre, and devoured Took-Moosh-Woot’s body.

Seeing that the people had failed to protect one of their own, the sun grew angry and abandoned the sky. In his wake, the skies grew dark and began to fill with heavy storm clouds. Seeing this, Uyot gathered the people together and told them to build boats, because a storm was coming. Soon, a great rain began to pour down, and the wind began to rage. The people got into their boats, and soon a flood came and lifted them up. The people sang their sacred songs so they could hear each other over the storm and keep their boats together. Some people did not sing the sacred songs properly, and trailed behind the main fleet. They would be the foreigners. Others did not memorize the sacred songs at all, and were swept away in the flood to the distant edges of the world, where they would become the Kastyanos [2] and the Oona [3].

Eventually, the flood waters receded and the people landed in the valley of the Ataaxpaala (OTL: Mississippi River). They were now safe, but the sun still refused to shine. Uyot saw this, and declared “now that one of us has died, all of us must die. Took-Moosh-Woot will take us all with him. From now on, all humans must die.” Saying this he himself lay down on his deathbed and prepared to pass on.

Before he died, he prophesied that a great fire would develop in the east. He summoned Coyote, and told him to go east to fetch the fire for his funeral pyre. Coyote followed his instructions, and went east. There, he saw a great fire on the horizon, and ran after it. He chased it, but the more he ran towards it the further away it seemed.

Meanwhile, Uyot died. His family gathered his wood for his body, and burnt it. From far away, Coyote saw the fire and turned to run towards it. As he got closer, Uyot’s family saw him coming and surrounded the fire, but Coyote kept running towards it. They feared that Coyote would leap over their heads, so fast and hard he was running, so they sent the strongest of their number to drag over the boats they had used to float over the floodwaters. The people then stood on the boats, and sang their sacred songs once again, beseeching the boats to carry them to Coyote so they could fight him. The boats transformed into horses, and the family rode against Coyote, chasing him away forevermore.

Glimpsing their brave actions from over the horizon where he had been distracting Coyote from his son’s funeral, the sun rose into the sky once again, shining on the brave sun-born, who had now claimed their place as the leaders of the people, while Took-Moosh-Woot’s people were relegated to be workers of the earth and hewers of wood. Uyot rose again to follow his father across the sky as the moon, giving the world light even when there was no sun.

[1] Referring to a constellation of stars around the North Star, this appears like a hand with an amputated finger.

[2] Whites

[3] Blacks

This story was based on myths I read here and here, which I found through www.native-languages.org

It looks like the Mississippian people considered themselves the best among humans. Am I detecting the foundations of ethnocentric thought there?

Last edited:

twovultures

Donor

It looks like the Mississippian people considered themselves the best among humans. Am I detecting the foundations of ethnocentric thought there?

This is true of many if not all ethnic groups ever, on some level

Danbensen said:Also looks like the Mississippians held on until European contact. Good for them!

They'll survive in greater numbers and more organized ITTL, but IOTL, there does seem to have been one Mississippian culture that survived well into European contact, the Natchez.

Berserker said:very, very awesome!

Thanks! I didn't do much, just synthesized some myths with some historical events. For example, the bit about the sun having a kid with a woman at the edge of the world comes from a claim by Ponce De Leon to be the son of the sun to impress a Native American chief. The significance of the descendants of the Sun vs. the descendants of the North Star will become apparent later.

twovultures

Donor

The Timetic Empire

As a new religion that divided history dawned in Eurasia, North Columbia saw the rise of a new empire. Although outside of the spheres of empire building in Middle Columbia, the chieftainships of the northeast had been developing over an entire millennium. As they grew over the years, fighting, merging, and breaking apart, they became better and better at managing their conquests. Although it lacked writing at this time, the southeast was still ripe for the creation of a great empire.

The empire’s mark came with the creation of the Great Solar Temple (near OTL’s Holly Bluff Site) around 0 A.D. Built in the valley of the Ataaxpaala River, this great earthwork monument consisting of a maze-like set of concentric circles was larger than anything that had previously been built in North Columbia. Around the time its construction started, the neighboring polities stopped building mounds. They no longer had the manpower to make their own religious centers. They had been forced to pay tribute to the first Emperor in North Columbia, known through oral history as “Chung-itsch-nich”, and every year were obligated to send able-bodied men to create monuments dedicated to his glory, neglecting their own spiritual monuments to tend to those of their conqueror. With the largest and only new earthworks around, the Great Solar Temple quickly became a center of religious pilgrimage. People came bearing offerings such as peccaries, copper jewelry and tools, and ‘fluffy dogs’, special breeds kept to make clothing from their hair which were a rough Columbian equivalent to sheep-and whose closest breeding centers were hundreds of miles to the north, showing the reach that the Great Solar Temple had.

Chung-itsch-nich’s empire stretched alongthe lower 3rd of the Ataaxpaala. The cultural sphere of his empire would move far beyond the river, however. Members of the noble class of his empire would ride out on conquests of their own, taking over foreign kingdoms and remolding them to resemble that of Chung-itsch-nich, with cities built along almost identical urban plans to settlements around the Solar Temple and copycat versions of the great circular mound works.

The conquering nobles would bring cultural as well as physical duplications of their homeland. The social mobility that had existed previously in the southeast began to erode, as family castes enforced people’s social positions and meant that even the peasants who distinguished themselves in battle could no longer take the title of nobility, unless they managed to successfully conceal their background-not easy, as nobles were expected to be able to recite their lineage going back generations.

Chung-itsch-nich’s heirs would spread what would become known as the Timetic cultural sphere over the southeast of North Columbia throughout the first millennium after the birth of Christianity. Although foreign conquerors would eventually break into the southeast, the cultural legacy of the Timetic people still remains.

The modern Timetic people continue to tell stories of Chung-itsch-nich’s empire, though the exact circumstances of its rise, existence and fall are shrouded in myth. The common thread running through these myths was that Chung-itsch-nich was the descendant of Uyot, a demigod who was born to the sun in the far west. Uyot was a brave leader but, after events outside of his control, his people were forced to leave from their home to the southeast.

Another common thread in the stories is the existence of ‘lower people’-people whose failure to act morally condemned them and their descendants to servitude of the ‘sun-born’. This was the origin of the caste system that in some ways continues to hold in the swampy southeast of North Columbia.

Despite the oppressive nature of the caste system, it had some mitigating factors-enough, at least, to guarantee its survival in the face of colonialist powers who wanted to reduce captured and conquered Columbians to a brutal, industrial slavery that arguably was worse than the caste system’s indignities.

Firstly, caste was inherited through the mother. This meant that lower caste men could-and did-marry ‘upward’ and produce children that were raised into the higher caste. In some areas, the upper castes did not marry among each-other, considering it akin to incest, and constantly married into lower castes, thus guaranteeing at least the hope of social improvement for lower caste males. The matrilineal system did create problems for upper caste men who wanted their sons to have lives of privilege, and probably created the proliferation of ‘middle castes’, classes of artists or warriors that are above peasants but below the nobility and priests in the southeast. Although not part of the religious myth that justified the caste system, their creation was a political necessity to get powerful men to accept the matrilineal caste system.

Secondly, castes gave privileges as well as responsibilities. Even the lowest peasant castes were guaranteed access to land to work. If one chiefdom or fiefdom became overcrowded, the local leader was obligated to ‘gift’ peasants to his neighbors so they could have land to work. Peasants were entitled to keep a portion of their harvest no matter what taxes or demands were levied on them. Land was kept communally by the village, and access to it was guaranteed to those within the caste system, thus keeping an incentive for people to identify within their caste. This would later cause problems as the Columbias were forcefully integrated into the world, and people outside the caste system sought to make a living alongside the Timetic peoples.

Thirdly, the benefits of caste also spread across other boundaries in society. The Sun-Born were meant to rule, and as the descendants of Uyot they had the right to claim rulership regardless of sex. Although future European historians would praise the northeastern republics as an example of equality, these often relegated women outside the halls of power. While it is true that women’s agricultural societies (and weaving societies, after the Vinland Interchange) held much power behind the scenes and chose leaders and village representatives, women themselves could not become chiefs or emissaries to the governments of these republics, except under very, very unique circumstances.

Within the southeast, however, many Queens and Empresses rose to power, their gender unquestioned as their birth gave them divine right to rule. The cultural template of powerful queens continues to exist to this day among the cultures of the southeast, as any visitor can see in the poem “Boudicca Spoke to Uyot’s Daughters” written in several languages on the monument/grave of the Aligosãyãwi leader Jeffrey Rowland. Even the great Columbian modernizer was bound in some ways to the precedents that Chung-itsch-nich had set almost 2,000 years before his birth.

As a new religion that divided history dawned in Eurasia, North Columbia saw the rise of a new empire. Although outside of the spheres of empire building in Middle Columbia, the chieftainships of the northeast had been developing over an entire millennium. As they grew over the years, fighting, merging, and breaking apart, they became better and better at managing their conquests. Although it lacked writing at this time, the southeast was still ripe for the creation of a great empire.

The empire’s mark came with the creation of the Great Solar Temple (near OTL’s Holly Bluff Site) around 0 A.D. Built in the valley of the Ataaxpaala River, this great earthwork monument consisting of a maze-like set of concentric circles was larger than anything that had previously been built in North Columbia. Around the time its construction started, the neighboring polities stopped building mounds. They no longer had the manpower to make their own religious centers. They had been forced to pay tribute to the first Emperor in North Columbia, known through oral history as “Chung-itsch-nich”, and every year were obligated to send able-bodied men to create monuments dedicated to his glory, neglecting their own spiritual monuments to tend to those of their conqueror. With the largest and only new earthworks around, the Great Solar Temple quickly became a center of religious pilgrimage. People came bearing offerings such as peccaries, copper jewelry and tools, and ‘fluffy dogs’, special breeds kept to make clothing from their hair which were a rough Columbian equivalent to sheep-and whose closest breeding centers were hundreds of miles to the north, showing the reach that the Great Solar Temple had.

Chung-itsch-nich’s empire stretched alongthe lower 3rd of the Ataaxpaala. The cultural sphere of his empire would move far beyond the river, however. Members of the noble class of his empire would ride out on conquests of their own, taking over foreign kingdoms and remolding them to resemble that of Chung-itsch-nich, with cities built along almost identical urban plans to settlements around the Solar Temple and copycat versions of the great circular mound works.

The conquering nobles would bring cultural as well as physical duplications of their homeland. The social mobility that had existed previously in the southeast began to erode, as family castes enforced people’s social positions and meant that even the peasants who distinguished themselves in battle could no longer take the title of nobility, unless they managed to successfully conceal their background-not easy, as nobles were expected to be able to recite their lineage going back generations.

Chung-itsch-nich’s heirs would spread what would become known as the Timetic cultural sphere over the southeast of North Columbia throughout the first millennium after the birth of Christianity. Although foreign conquerors would eventually break into the southeast, the cultural legacy of the Timetic people still remains.

The modern Timetic people continue to tell stories of Chung-itsch-nich’s empire, though the exact circumstances of its rise, existence and fall are shrouded in myth. The common thread running through these myths was that Chung-itsch-nich was the descendant of Uyot, a demigod who was born to the sun in the far west. Uyot was a brave leader but, after events outside of his control, his people were forced to leave from their home to the southeast.

Another common thread in the stories is the existence of ‘lower people’-people whose failure to act morally condemned them and their descendants to servitude of the ‘sun-born’. This was the origin of the caste system that in some ways continues to hold in the swampy southeast of North Columbia.

Despite the oppressive nature of the caste system, it had some mitigating factors-enough, at least, to guarantee its survival in the face of colonialist powers who wanted to reduce captured and conquered Columbians to a brutal, industrial slavery that arguably was worse than the caste system’s indignities.

Firstly, caste was inherited through the mother. This meant that lower caste men could-and did-marry ‘upward’ and produce children that were raised into the higher caste. In some areas, the upper castes did not marry among each-other, considering it akin to incest, and constantly married into lower castes, thus guaranteeing at least the hope of social improvement for lower caste males. The matrilineal system did create problems for upper caste men who wanted their sons to have lives of privilege, and probably created the proliferation of ‘middle castes’, classes of artists or warriors that are above peasants but below the nobility and priests in the southeast. Although not part of the religious myth that justified the caste system, their creation was a political necessity to get powerful men to accept the matrilineal caste system.

Secondly, castes gave privileges as well as responsibilities. Even the lowest peasant castes were guaranteed access to land to work. If one chiefdom or fiefdom became overcrowded, the local leader was obligated to ‘gift’ peasants to his neighbors so they could have land to work. Peasants were entitled to keep a portion of their harvest no matter what taxes or demands were levied on them. Land was kept communally by the village, and access to it was guaranteed to those within the caste system, thus keeping an incentive for people to identify within their caste. This would later cause problems as the Columbias were forcefully integrated into the world, and people outside the caste system sought to make a living alongside the Timetic peoples.

Thirdly, the benefits of caste also spread across other boundaries in society. The Sun-Born were meant to rule, and as the descendants of Uyot they had the right to claim rulership regardless of sex. Although future European historians would praise the northeastern republics as an example of equality, these often relegated women outside the halls of power. While it is true that women’s agricultural societies (and weaving societies, after the Vinland Interchange) held much power behind the scenes and chose leaders and village representatives, women themselves could not become chiefs or emissaries to the governments of these republics, except under very, very unique circumstances.

Within the southeast, however, many Queens and Empresses rose to power, their gender unquestioned as their birth gave them divine right to rule. The cultural template of powerful queens continues to exist to this day among the cultures of the southeast, as any visitor can see in the poem “Boudicca Spoke to Uyot’s Daughters” written in several languages on the monument/grave of the Aligosãyãwi leader Jeffrey Rowland. Even the great Columbian modernizer was bound in some ways to the precedents that Chung-itsch-nich had set almost 2,000 years before his birth.

I thought I'd give a few thoughts on colonization:

I don't expect Europeans to be able impose large scale slavery at will but I would expect them to be able to make incursions on the peripheral and coastal areas of North America and play off local animosities to their advantage in the way that the British did in India.

I personally think that full blown direct and brutal conquest (like Cortez and Pizarro) of a strong and resilient culture could unite people far and wide or at least, engender serious and universal mistrust of Europeans. Because these people would have horses, metal weapons and larger more established populations, conquest would mean huge expenditures of European blood and money for questionable material gain. After all, there are none of the huge and ready supplies of gold that tempted the conquistadors. The parent country would be weakened in Europe and opportunistic rivals might even reverse their gains in the new world. Far safer and more logical for a country to take it slowly, and establish ever more direct power where possible.

European colonies would probably begin in places like the Carolinas and other regions East of the Appalaichians which are closer to Europe, could serve as sort of a brigde to the Caribbean islands (likely to be the first things to be colonized, at on least the smaller ones) and are more removed from the more populous regions to the West. There they could -and probably would- establish plantations worked by native labor, perhaps aquired from both European and native slave traders. I would expect Europeans themselves to settle more readily in cooler climates up North as it would likely appear closer to Europe in climate.

I suppose one place that might be colonized relatively directly and similarly to OTL is Brazil. The Amazon could be enough of a barrier that the Europeans could set up and expand colonies with much less difficulty. In fact, Brazil might be something of an odditidy in that it would be a mostly non-native nation in mainland South Columbia.

Can't wait to see how this all develops.

I don't expect Europeans to be able impose large scale slavery at will but I would expect them to be able to make incursions on the peripheral and coastal areas of North America and play off local animosities to their advantage in the way that the British did in India.

I personally think that full blown direct and brutal conquest (like Cortez and Pizarro) of a strong and resilient culture could unite people far and wide or at least, engender serious and universal mistrust of Europeans. Because these people would have horses, metal weapons and larger more established populations, conquest would mean huge expenditures of European blood and money for questionable material gain. After all, there are none of the huge and ready supplies of gold that tempted the conquistadors. The parent country would be weakened in Europe and opportunistic rivals might even reverse their gains in the new world. Far safer and more logical for a country to take it slowly, and establish ever more direct power where possible.

European colonies would probably begin in places like the Carolinas and other regions East of the Appalaichians which are closer to Europe, could serve as sort of a brigde to the Caribbean islands (likely to be the first things to be colonized, at on least the smaller ones) and are more removed from the more populous regions to the West. There they could -and probably would- establish plantations worked by native labor, perhaps aquired from both European and native slave traders. I would expect Europeans themselves to settle more readily in cooler climates up North as it would likely appear closer to Europe in climate.

I suppose one place that might be colonized relatively directly and similarly to OTL is Brazil. The Amazon could be enough of a barrier that the Europeans could set up and expand colonies with much less difficulty. In fact, Brazil might be something of an odditidy in that it would be a mostly non-native nation in mainland South Columbia.

Can't wait to see how this all develops.

Last edited:

The butterflies might be even bigger than that. We might not get any European colonization at all.

The very earliest European efforts on the American continents (versus the Caribbean) were all bent on getting to the Pacific Ocean and China. Even Monteczuma's gold and the silver of Potosi were only really valuable because they could be used to trade with China. The enormous amount of money flowing into Europe from the Americas (or from China through the Americas) made other people try their hand at colonization, and generally they failed miserably. The Jamestown colonists struggled for years, first just to stay alive, and later to find anything they could do that might earn money. It was seven years before they figured out they could grow tobacco there profitably.

I think strong local resistance would have put the kibosh on all of that. A disease-resistant Colombian horse-culture would be more like China or India, civilizations European conquerors only tackled after 150 years of extracting wealth out of the Americas. And perhaps in TTL, no one in Europe thinks that they can realistically conquer and enslave an entire civilization. I mean, when has that ever happened before?

Instead we might get European trading posts and slave-raiding/piracy across the eastern Colombian coasts, maybe some actual conquest in the Caribbean islands, but mostly European culture and people diffusing through Colombian kingdoms, like in 17th century south Africa and Asia.

The very earliest European efforts on the American continents (versus the Caribbean) were all bent on getting to the Pacific Ocean and China. Even Monteczuma's gold and the silver of Potosi were only really valuable because they could be used to trade with China. The enormous amount of money flowing into Europe from the Americas (or from China through the Americas) made other people try their hand at colonization, and generally they failed miserably. The Jamestown colonists struggled for years, first just to stay alive, and later to find anything they could do that might earn money. It was seven years before they figured out they could grow tobacco there profitably.

I think strong local resistance would have put the kibosh on all of that. A disease-resistant Colombian horse-culture would be more like China or India, civilizations European conquerors only tackled after 150 years of extracting wealth out of the Americas. And perhaps in TTL, no one in Europe thinks that they can realistically conquer and enslave an entire civilization. I mean, when has that ever happened before?

Instead we might get European trading posts and slave-raiding/piracy across the eastern Colombian coasts, maybe some actual conquest in the Caribbean islands, but mostly European culture and people diffusing through Colombian kingdoms, like in 17th century south Africa and Asia.

twovultures

Donor

There definitely will be continued interest in the Columbias ITTL. The larger societies will produce more goods-tobacco, gold, leather, etc-that Europeans will want.

Conversely, while Native Columbian societies will have more advanced technology ITTL, it will still be behind Eurasian technology in many ways-meaning that Europeans will have plenty of curiosities to trade with, encouraging the Columbians to let them settle in their territory-and therefore get a toehold. While European colonialism can't get as far as OTL, it will still happen. Christian Europeans have a lot to gain from the Age of Exploration, too much to ignore even with setbacks.

Conversely, while Native Columbian societies will have more advanced technology ITTL, it will still be behind Eurasian technology in many ways-meaning that Europeans will have plenty of curiosities to trade with, encouraging the Columbians to let them settle in their territory-and therefore get a toehold. While European colonialism can't get as far as OTL, it will still happen. Christian Europeans have a lot to gain from the Age of Exploration, too much to ignore even with setbacks.

twovultures

Donor

Around 300 AD, the Jacal culture developed in the southern Yut Mountains. This was not a culture that sprang out of nowhere-it had evolved along a continuum from the earliest days horse domestication, when bands of hunters first began to specialize in managing wild horses. These bands had founded villages and camps along the desert rivers and cliff tops, adopting maize, turkey, and peccaries from the south, moving in some instances towards becoming farming peoples in the vein of the Middle Columbians despite the dryness of their environment. The early rise of cold-resistant maize and the presence of large domestics helped them overcome the environmental difficulties that restricted their farming and propelled the creation of farming villages in the mountains.

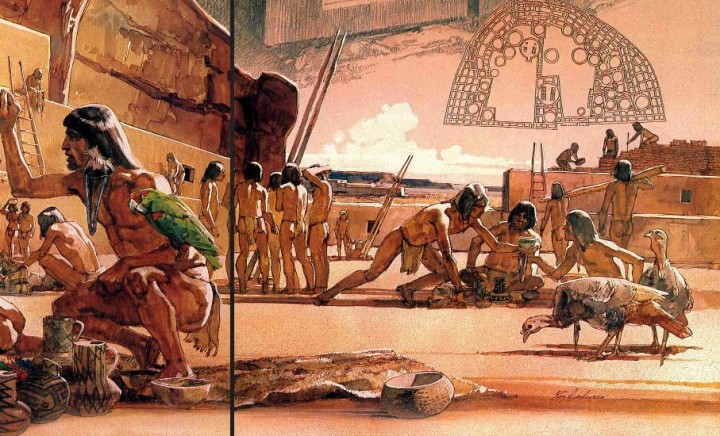

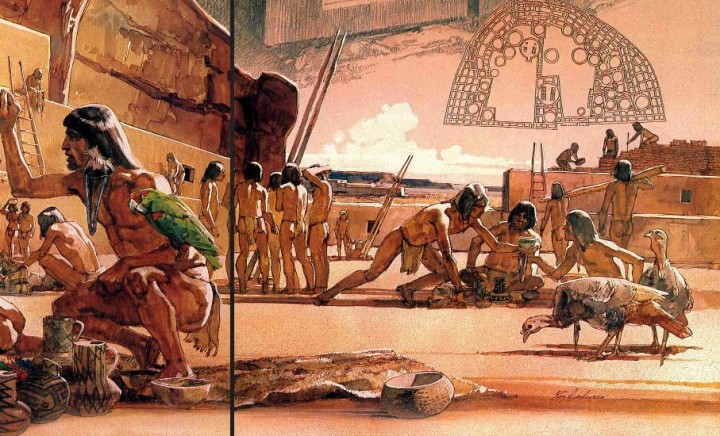

What set the Jacal apart from the earlier iterations of its ancestral culture was scale. Many more people packed into the villages, with many adobe houses squeezed behind walls as a defensive measure to fight off nomadic raiders from the plains. Plentiful maize as well as the mountain-adapted razorback peccary breed created the numbers necessary to sustain the Jacal culture. Trade with Middle Columbia gave it the innovations necessary to create a unique mark on the cultural landscape.

Jacal village, with an imported Middle Columbian parrot.

One of those changes came in humble seed bags, carried by merchants across the deserts along with more valuable trade goods such as macaw feathers. Potatoes had become deeply established in the highlands of Middle Columbia, producing much more food in the more marginal land than the native maize agriculture. In the Yut Mountains, it was quickly recognized as a potentially valuable plant-to feed peccaries. The strange, lumpy root did not strike most of the sedentary farmers as their first choice to put on their plates, but they needed rich food for their peccaries. After millennia of breeding, razorbacks were giving birth to 3-12 young in a single litter, as opposed to the 1-4 litters of our collared peccaries. Although the higher numbered litters tended to contain runts that didn’t survive long, the elevated birth rate and subsequent numbers meant that peccaries had to be catered too with feed in addition to letting them mast in the wild, and the potato seemed to be good animal feed.

It was semi-sedentary farmers who realized the potential of the potato to feed people. Although the Jacal culture produced many permanent villages, it did not consist only of such settlements. Pastoralist tribes who spent one part of the year driving their herds to grazing ground and another part farming quickly recognized the usefulness of the potato, which was grown by settled peoples they generally considered friends and allies-and also competitors, at some times. By simply growing underground, it was much harder for wild animals to eat than maize or beans. Potatoes required much less care or work than other plants, which meant that they thrived in untended gardens, leaving their planters much less to worry about when on the road.

Seeing these part-time farmers become ever more dependent on potatoes, the village farmers realized that they were overlooking a potentially useful crop. The fact that the potato survived where maize didn’t, sustaining entire villages during bad years where frost came too early contributed to the acceptance of this last-resort animal fodder as a food crop. Using the potato, the Jacal were able to spread northward over the Yut mountains, using their knowledge of building on cliffs to eke out a living on rough land were maize would have been useless.

The second major change was writing. There were no great empires in the Yut Mountains, no large bureaucracies waiting for a new way to process information. Although future archaeologists would point to the acceptance of writing by the religious leaders of the Jacal as the turning point in its acceptance, the modern descendants of the Jacal are skeptical-their own religion is both personal and ubiquitous in almost every aspect of their society, and while some individuals hold positions of religious authority, their spiritual landscape does not have a clerical structure comparable to the noble-priest class of classic Middle Columbia or the Church of medieval Christendom.

Nonetheless, religion was important in the early days of the Jacal, and for some of the religious projects that the disparate villages undertook-such as creating common roads for use in pilgrimage-required storing information (such as promises to provide labor or protection for laborers, as well as engineering information) and coordinating tasks so the roads could be constructed efficiently.

Although they did not have a professional bureaucracy, undertaking such practices of organized religion did pose challenges that writing helped solve. The Jacal would adopt the idea of writing from the same visiting merchants that had brought them potatoes, creating a hieroglyphic script they imprinted on clay tablets and painted onto the walls of their homes to commemorate promises, prophecies, victories, genealogies and other such interests.

Jacal pot with proto-hieroglyphic design.

What set the Jacal apart from the earlier iterations of its ancestral culture was scale. Many more people packed into the villages, with many adobe houses squeezed behind walls as a defensive measure to fight off nomadic raiders from the plains. Plentiful maize as well as the mountain-adapted razorback peccary breed created the numbers necessary to sustain the Jacal culture. Trade with Middle Columbia gave it the innovations necessary to create a unique mark on the cultural landscape.

Jacal village, with an imported Middle Columbian parrot.

One of those changes came in humble seed bags, carried by merchants across the deserts along with more valuable trade goods such as macaw feathers. Potatoes had become deeply established in the highlands of Middle Columbia, producing much more food in the more marginal land than the native maize agriculture. In the Yut Mountains, it was quickly recognized as a potentially valuable plant-to feed peccaries. The strange, lumpy root did not strike most of the sedentary farmers as their first choice to put on their plates, but they needed rich food for their peccaries. After millennia of breeding, razorbacks were giving birth to 3-12 young in a single litter, as opposed to the 1-4 litters of our collared peccaries. Although the higher numbered litters tended to contain runts that didn’t survive long, the elevated birth rate and subsequent numbers meant that peccaries had to be catered too with feed in addition to letting them mast in the wild, and the potato seemed to be good animal feed.

It was semi-sedentary farmers who realized the potential of the potato to feed people. Although the Jacal culture produced many permanent villages, it did not consist only of such settlements. Pastoralist tribes who spent one part of the year driving their herds to grazing ground and another part farming quickly recognized the usefulness of the potato, which was grown by settled peoples they generally considered friends and allies-and also competitors, at some times. By simply growing underground, it was much harder for wild animals to eat than maize or beans. Potatoes required much less care or work than other plants, which meant that they thrived in untended gardens, leaving their planters much less to worry about when on the road.

Seeing these part-time farmers become ever more dependent on potatoes, the village farmers realized that they were overlooking a potentially useful crop. The fact that the potato survived where maize didn’t, sustaining entire villages during bad years where frost came too early contributed to the acceptance of this last-resort animal fodder as a food crop. Using the potato, the Jacal were able to spread northward over the Yut mountains, using their knowledge of building on cliffs to eke out a living on rough land were maize would have been useless.

The second major change was writing. There were no great empires in the Yut Mountains, no large bureaucracies waiting for a new way to process information. Although future archaeologists would point to the acceptance of writing by the religious leaders of the Jacal as the turning point in its acceptance, the modern descendants of the Jacal are skeptical-their own religion is both personal and ubiquitous in almost every aspect of their society, and while some individuals hold positions of religious authority, their spiritual landscape does not have a clerical structure comparable to the noble-priest class of classic Middle Columbia or the Church of medieval Christendom.

Nonetheless, religion was important in the early days of the Jacal, and for some of the religious projects that the disparate villages undertook-such as creating common roads for use in pilgrimage-required storing information (such as promises to provide labor or protection for laborers, as well as engineering information) and coordinating tasks so the roads could be constructed efficiently.

Although they did not have a professional bureaucracy, undertaking such practices of organized religion did pose challenges that writing helped solve. The Jacal would adopt the idea of writing from the same visiting merchants that had brought them potatoes, creating a hieroglyphic script they imprinted on clay tablets and painted onto the walls of their homes to commemorate promises, prophecies, victories, genealogies and other such interests.

Jacal pot with proto-hieroglyphic design.

Last edited:

I assume that the Yut mountains are the Rockies. If these "visiting merchants" brought potatoes, then North-South trade must be very well-developed. Take that Jared Diamond.

Yeah, how does North-South trade work? Boats? Just bigger civilizations in Mesoamerica and Peru having more resources to fund longer-ranging exploration?

Llama/horse caravans across the length of the Andes and Rockies=awesome. But maybe boats up the west coast would be easier. What would that be? The Potato Route? The Chocolate Route?

Llama/horse caravans across the length of the Andes and Rockies=awesome. But maybe boats up the west coast would be easier. What would that be? The Potato Route? The Chocolate Route?

What would that be? The Potato Route? The Chocolate Route?

I vote Tabaco route

and a very interesting update. are there going to be warrior castes like the eagle and the jaguar in mesoamerica like OTL??

twovultures

Donor

I assume that the Yut mountains are the Rockies.

That's correct. I should probably put out a glossary of alt historical v. historical names for this universe.

I think this theory is somewhat misunderstood. Jared Diamond claimed that crops would spread slowly on an east-west axis, and with that would come a slower spread of sedentary societies, but trade of physical items isn't limited by a north south axis.If these "visiting merchants" brought potatoes, then North-South trade must be very well-developed. Take that Jared Diamond.

While I'm probably one of his bigger defenders on this board, this is one of his weaker claims. Maize ultimately did spread along a north-south axis, and arguably it went from Mexico to north of the Rio Grande faster than it went east from New Mexico to the Mississippi. While potatoes do take some time to adapt to northern latitudes to become good food crop (it took a while for them to get used to European temperate weather, for example) they can and have moved north, just like maize.

Danbensen said:Yeah, how does North-South trade work? Boats? Just bigger civilizations in Mesoamerica and Peru having more resources to fund longer-ranging exploration?

North-South trade between Mesoamerica and North America actually exists IOTL. Macaw feathers have been discovered in ancient Pueblo ruins, and show that trade across the deserts on foot is possible. ITTL, horses make this trade route faster and easier.

The *Peru-*Mexico trade on the other hand is maritime, thanks to the shipbuilding technology developed by the Awapi.

Berserker said:are there going to be warrior castes like the eagle and the jaguar in mesoamerica like OTL??

The *Pueblo culture is more egalitarian than the *Mesoamerican, and so is less likely to develop such castes. That said, it's also going to be much more widespread and in greater military conflict with the Plains Indians, so it's possible that equivalent castes could develop in some limited areas.

EDIT: And of as 9 Fanged pointed out, 'caste' is not exactly the right term. More of a knightly order, I guess?

Caste really isn't the right word. It implies it's hereditary or something, when in reality the Eagle and Jaguar Warriors were warrior societies similar to the ones in Plains societies, such as the Dog Soldiers, Kit Foxes, etc. Eagles and Jaguars would be accorded certain privileges, but it was because of the rank that they earned, as joining either society was a matter of merit, not of birth.and a very interesting update. are there going to be warrior castes like the eagle and the jaguar in mesoamerica like OTL??

twovultures

Donor

The Gaayu’be’ena’a is known to the Columbians who inhabit its successor states as “The Empire of a Thousand Years”. More critical historians (usually foreigners) tend to divide the Gaayu’be’ena’a’s history into two segments, one of 600 and one of 400 years. In the first segment, the empire grew and solidified its control, reducing neighboring kingdoms into puppet states and using a system of patronage, replacing conquered leaders with governors, and repatriation within its borders to merge fully controlled kingdoms into its metropole.

Around 400 AD, the Gaayu’be’ena’a entered the second stage of their empire, which would consist of fending off threats foreign and domestic to the gains their empire had made. They did not get off to a very good start.

Some of the greatest horsemen of the Columbias lived in the deserts north of Middle Columbia. It was in these lands that horses had first been domesticated, and the desert people had been refining their horsemanship since time immemorial. As a wave of unusually moist weather hit the deserts, the herds of the desert nomads multiplied, and the nomads found that it was now easier to travel in numbers as water was less of an issue. Having traded crafted goods from their southern neighbors for centuries, it now occurred to them that they could take the luxuries the wealthiest among them enjoyed by force.

The first wave of these migrants rode south into the Gaayu’be’ena’a’s northern border region around 400 AD. There, they sent an emissary to the local governor, 7 Ocelot Vine, requesting safe passage through the land. 7 Ocelot Vine surmised (correctly) that the nomads were planning to take up a life of banditry within the Gaayu’be’ena’a. He responded by cutting off the emissary’s head and placing it on a pike outside of his palace as a warning to the insolent barbarians that they were to stay in the desert. Outraged, the entire tribe descended on the G’aayu’bena’a and laid waste to everything in their path, stealing horses, killing men, raping women, and enslaving children as they burned their way southward. 7 Ocelot Vine rode out with his men to meet them in battle, knowing that if he failed to contain them he would be at best completely disgraced and reduced to a social pariah, at worse executed for his incompetence.

He feared his emperor’s wrath, but he should have feared the invaders more. Upon sighting their camp, he ordered a full frontal assault, leading the charge himself. His army, of course, was seen approaching the camp. He hoped it would be, and that their might would frighten the silly savages away. All it did was give the nomads time to prepare.

As soon as the army was in range, a wave of lethal javelins sailed through the air from the camp, propelled by atlatls which gave them a far longer range than the spears used by the Gaayu’be’ena’a. The imperial spears were meant for thrusting over throwing anyway, to take down horseback riders in close combat. The nomads knew this, and had no intention of giving the imperial infantry the chance to fight them at close range. That honor would be reserved for the treacherous 7 Ocelot and his cronies, who fought on horseback as befits a noble.

Although his ranks had been thinned by the projectiles, 7 Ocelot Vine pressed on, leading the cavalry far ahead of the main army. He believed that noblemen trained from youth to fight on horses would make short work of the lowly foreigners. It was yet another blunder. The desert people used loops of cloth attached to their saddles as stirrups for balance. This made them capable of feats of cavalry archery that would have left 4 Dog Reed Bundle green with jealousy, and made them capable of fighting much more securely on horseback than their barefoot adversaries.

The proud nobility of the Gaayu’be’ena’a were unhorsed one by one, years of training wasted in the face of superior technology. Seeing the nobility defeated, the common footsoldiers abandoned 7 Ocelot Vine to his death and fled the battle in terror, contributing to an atmosphere of chaos as bands of deserters joined the nomads in their looting.

This original band of marauding nomads would continue moving south. Although the Gaayu’be’ena’a army seemed incapable of permanently stopping them, bit by bit the generals learned how to best engage them, grinding them down in a slow attrition.

Moving south past the borderlands of the Gaayu’be’ena’a, the nomads united under a charismatic visionary named Moon Rabbit. He is credited with settling them, declaring that the site for their city would be the place where he saw a sacred sign-a flock of hummingbirds larger than any they had seen before. The nomads would become the Witzilintak (People of the Hummingbirds), establishing a kingdom that would absorb the ‘civilized’ norms of their neighbors and integrate into Middle Columbia.

For the Gaayu’be’ena’a, the defeat was a terrible shock. Their military leaders had been proven incompetent, and their natural place in the hierarchy of things was now in question. Raids continued in the north, as more nomad tribes rode into the pastureland that the Witzilintak had abandoned and took up banditry. Something would have to be done to assuage the people’s existential angst, if the Empire was to survive.

Around 400 AD, the Gaayu’be’ena’a entered the second stage of their empire, which would consist of fending off threats foreign and domestic to the gains their empire had made. They did not get off to a very good start.

Some of the greatest horsemen of the Columbias lived in the deserts north of Middle Columbia. It was in these lands that horses had first been domesticated, and the desert people had been refining their horsemanship since time immemorial. As a wave of unusually moist weather hit the deserts, the herds of the desert nomads multiplied, and the nomads found that it was now easier to travel in numbers as water was less of an issue. Having traded crafted goods from their southern neighbors for centuries, it now occurred to them that they could take the luxuries the wealthiest among them enjoyed by force.

The first wave of these migrants rode south into the Gaayu’be’ena’a’s northern border region around 400 AD. There, they sent an emissary to the local governor, 7 Ocelot Vine, requesting safe passage through the land. 7 Ocelot Vine surmised (correctly) that the nomads were planning to take up a life of banditry within the Gaayu’be’ena’a. He responded by cutting off the emissary’s head and placing it on a pike outside of his palace as a warning to the insolent barbarians that they were to stay in the desert. Outraged, the entire tribe descended on the G’aayu’bena’a and laid waste to everything in their path, stealing horses, killing men, raping women, and enslaving children as they burned their way southward. 7 Ocelot Vine rode out with his men to meet them in battle, knowing that if he failed to contain them he would be at best completely disgraced and reduced to a social pariah, at worse executed for his incompetence.

He feared his emperor’s wrath, but he should have feared the invaders more. Upon sighting their camp, he ordered a full frontal assault, leading the charge himself. His army, of course, was seen approaching the camp. He hoped it would be, and that their might would frighten the silly savages away. All it did was give the nomads time to prepare.

As soon as the army was in range, a wave of lethal javelins sailed through the air from the camp, propelled by atlatls which gave them a far longer range than the spears used by the Gaayu’be’ena’a. The imperial spears were meant for thrusting over throwing anyway, to take down horseback riders in close combat. The nomads knew this, and had no intention of giving the imperial infantry the chance to fight them at close range. That honor would be reserved for the treacherous 7 Ocelot and his cronies, who fought on horseback as befits a noble.

Although his ranks had been thinned by the projectiles, 7 Ocelot Vine pressed on, leading the cavalry far ahead of the main army. He believed that noblemen trained from youth to fight on horses would make short work of the lowly foreigners. It was yet another blunder. The desert people used loops of cloth attached to their saddles as stirrups for balance. This made them capable of feats of cavalry archery that would have left 4 Dog Reed Bundle green with jealousy, and made them capable of fighting much more securely on horseback than their barefoot adversaries.

The proud nobility of the Gaayu’be’ena’a were unhorsed one by one, years of training wasted in the face of superior technology. Seeing the nobility defeated, the common footsoldiers abandoned 7 Ocelot Vine to his death and fled the battle in terror, contributing to an atmosphere of chaos as bands of deserters joined the nomads in their looting.

This original band of marauding nomads would continue moving south. Although the Gaayu’be’ena’a army seemed incapable of permanently stopping them, bit by bit the generals learned how to best engage them, grinding them down in a slow attrition.

Moving south past the borderlands of the Gaayu’be’ena’a, the nomads united under a charismatic visionary named Moon Rabbit. He is credited with settling them, declaring that the site for their city would be the place where he saw a sacred sign-a flock of hummingbirds larger than any they had seen before. The nomads would become the Witzilintak (People of the Hummingbirds), establishing a kingdom that would absorb the ‘civilized’ norms of their neighbors and integrate into Middle Columbia.

For the Gaayu’be’ena’a, the defeat was a terrible shock. Their military leaders had been proven incompetent, and their natural place in the hierarchy of things was now in question. Raids continued in the north, as more nomad tribes rode into the pastureland that the Witzilintak had abandoned and took up banditry. Something would have to be done to assuage the people’s existential angst, if the Empire was to survive.

twovultures

Donor

It was a full century until the Gaayu’be’ena’a would seize back its place in the proper order of things by a clear and overwhelming victory-though as the political situation in the aftermath of that victory shows, it’s possible that earlier victories were denigrated and this particular one was elevated in the record. That said there was no shortage of depressing news over the course of that century for the Empire.

The scribes of the Gaayu’be’ena’a had carefully detailed the humiliations that their empire had suffered at the hands of the barbarians. It may seem strange that the power of writing should have been used to detail the empire’s problems rather than its glories, but the nameless bureaucrats who ordered the compilation of this information were playing a long game that would greatly pay off for the Empire. In the meantime, border governors used a mixture of gifts, bribes, and playing different bands against each-other to try and lessen the problem of nomad raiders.

When one of the hordes organizing on the northern border started to refuse to have any dealing with the imperial officials, the Imperial Court took notice. When reports came that a new chief named Coyote [1] was calling himself “Ahau of Mishwakan”, the court knew that it was time to act-Mishwakan was what the nomads called the Gaayu’be’ena’a’s Northern Province, and claiming kingship over it was clearly a direct challenge to the empire’s integrity.

Kaloomte B’alam 4 Spotted Deer sent out his best general, Dawn Horse, to face Coyote. Dawn Horse was a crafty tactician and a brilliant strategist. He was also a great reader, and brought with him a codex on bark paper known colloquially as “The Book of Shame”-detailing a military history of defeat and pyrrhic victories against the nomads.

He also brought with him a new kind of weapon, which was the main motivation for securing the Northern Province/Mishwakan. It bordered a desert area which contained metal ores that had previously been mined for their aesthetic properties. The metalsmiths of Middle Columbia had determined that these ores could be smelted, like copper. They mixed this metal with other metals, trying to create aesthetic alloys just as they did by mixing copper, silver, and gold. What they found was that when mixed with copper, this new metal created a strong alloy that could be shaped into a knife, a hoe, a tool that could cut wood or leather as efficiently as stone but could be more easily shaped to create a finer, more precise instrument. This metal was why Mishwakan was never abandoned, even in the face of the nomad threat, and it was part of what would allow Dawn Horse to add an epilogue of victory to the Book of Shame.

When he reached Mishwakan, he did not begin hunting down the desert peoples like his predecessors had. Instead, he organized levies of peasants to reinforce the fortifications of all towns in the area. He approached nomads who had come to trade, offering gifts of tobacco and promises of friendship-if they would keep him informed of the pretender-king.

When Coyote’s men began to launch attacks against Dawn Horse’s fortification, Dawn Horse doubled down. He did not pursue attackers, or march his men into the desert to face Coyote’s tribe. He did send out some punitive expeditions-small groups led by trusted guides to track down the camps and run lightning hit and run attacks on them, just to show that he could strike where he pleased on the Empire’s land.

Realizing that he had to make a move to cement his claim, Coyote gathered his men together to face Dawn Horse directly. Riding into battle, the two armies seemed pretty evenly matched-it was mostly cavalry against cavalry. But Dawn Horse had too much of an advantage.

Although both sides wore hardened leather armor, the Imperial Cavalry also wore bronze helmets over their heads and had many small bronze ‘coins’ sown onto their leather armor, providing extra protection from arrows. Their stirrups were made of carved hardwoods or bronze rather than cloth, making their footing more secure than the cloth or leather stirrups of their enemy [2]. Their horses were also larger-bred by noble classes to show off their strength, not run through the deserts. In a fight were they had to track down the enemy, these horses would be more tired than the small and hardy desert horses, but in a fight where the enemy came to them the larger horses would be rested, ready-and give their riders an advantage in a charge.

Assisting this ‘heavy cavalry’ were nomads who sided with Dawn Horse against Coyote. Equally well armed as their adversaries, they protected the flanks of the Imperial Cavalry and fired projectiles while Coyote’s army charged in.

When the battle was met, it was not immediately apparent that Coyote would lose. His army was extremely large, consisting of hardened desert men who did not fear the ‘soft’ imperials. But their arrows failed to penetrate their foe’s armor, and their clubs and obsidian axes shattered on the bronze helmets of the imperials. The imperial side used their thrusting spears to devastating effect. As the battle grew more intense and horses fell, warriors met on foot. There, the ability of the imperials to use their short bronze swords in close quarters gave them a great advantage over the nomads, whose less effective clubs and axes required a great deal of arm space to wield effectively and on a crowded battlefield lost some of their edge. Perhaps against a people who fought mere skirmishes or who honored the idea of one to one combat the nomads could have obtained that space, but the Gaayu’be’ena’a did not become the Thousand Year Empire by playing fair or doing anything small.

A new invention had kept Dawn Horse’s men well supplied during their stint in the north, and now the great wagons clattered onto the battlefield delivering foot soldiers right into the heart of the fight. In addition to giving extra men to crowd the battlefield and outnumber the enemy, the wagons appeared terrifying to the nomads, who had never seen such things used before. Combined with the imperial-allied ‘light cavalry’ which kept them from enacting a pincer movement, it became clear that the would-be lord of Mishwakan had lost the day. Coyote attempted to flee, but was killed by an arrow. Dawn Horse had now succeeded were all in the Empire had failed.

Perhaps the success had gotten to his head, which may explain why he immediately marched south and beheaded his former friend 4 Spotted Deer, taking the title of Kaloomte B’alam for himself. This was the other problem of the Gaayu’be’ena’a-changing of regime through usurpation and assassination. While a strong and popular leader like Dawn Horse could ensure stability when they took over, more commonly these violent takeovers often lead to bloodshed as the usurpers faced revolts by rivals seeking to take them off the throne in turn.

At least the northern tribes had been temporarily subdued. Disturbingly, though, part of Dawn Horse’s victory depended on bribing some of the nomads. It was a dependence that would grow, with lethal consequences for the empire.

[1] Quite possibly a name given to him by the scribes to denigrate him. Like other historical 'villains' such as the legendarily incompetent amateur warlord 2 Vulture Scribe, this was a name given to their post-mortem biographies.

[2] The Columbian equivalent of the Iron Stirrup.

The scribes of the Gaayu’be’ena’a had carefully detailed the humiliations that their empire had suffered at the hands of the barbarians. It may seem strange that the power of writing should have been used to detail the empire’s problems rather than its glories, but the nameless bureaucrats who ordered the compilation of this information were playing a long game that would greatly pay off for the Empire. In the meantime, border governors used a mixture of gifts, bribes, and playing different bands against each-other to try and lessen the problem of nomad raiders.

When one of the hordes organizing on the northern border started to refuse to have any dealing with the imperial officials, the Imperial Court took notice. When reports came that a new chief named Coyote [1] was calling himself “Ahau of Mishwakan”, the court knew that it was time to act-Mishwakan was what the nomads called the Gaayu’be’ena’a’s Northern Province, and claiming kingship over it was clearly a direct challenge to the empire’s integrity.

Kaloomte B’alam 4 Spotted Deer sent out his best general, Dawn Horse, to face Coyote. Dawn Horse was a crafty tactician and a brilliant strategist. He was also a great reader, and brought with him a codex on bark paper known colloquially as “The Book of Shame”-detailing a military history of defeat and pyrrhic victories against the nomads.

He also brought with him a new kind of weapon, which was the main motivation for securing the Northern Province/Mishwakan. It bordered a desert area which contained metal ores that had previously been mined for their aesthetic properties. The metalsmiths of Middle Columbia had determined that these ores could be smelted, like copper. They mixed this metal with other metals, trying to create aesthetic alloys just as they did by mixing copper, silver, and gold. What they found was that when mixed with copper, this new metal created a strong alloy that could be shaped into a knife, a hoe, a tool that could cut wood or leather as efficiently as stone but could be more easily shaped to create a finer, more precise instrument. This metal was why Mishwakan was never abandoned, even in the face of the nomad threat, and it was part of what would allow Dawn Horse to add an epilogue of victory to the Book of Shame.

When he reached Mishwakan, he did not begin hunting down the desert peoples like his predecessors had. Instead, he organized levies of peasants to reinforce the fortifications of all towns in the area. He approached nomads who had come to trade, offering gifts of tobacco and promises of friendship-if they would keep him informed of the pretender-king.

When Coyote’s men began to launch attacks against Dawn Horse’s fortification, Dawn Horse doubled down. He did not pursue attackers, or march his men into the desert to face Coyote’s tribe. He did send out some punitive expeditions-small groups led by trusted guides to track down the camps and run lightning hit and run attacks on them, just to show that he could strike where he pleased on the Empire’s land.

Realizing that he had to make a move to cement his claim, Coyote gathered his men together to face Dawn Horse directly. Riding into battle, the two armies seemed pretty evenly matched-it was mostly cavalry against cavalry. But Dawn Horse had too much of an advantage.

Although both sides wore hardened leather armor, the Imperial Cavalry also wore bronze helmets over their heads and had many small bronze ‘coins’ sown onto their leather armor, providing extra protection from arrows. Their stirrups were made of carved hardwoods or bronze rather than cloth, making their footing more secure than the cloth or leather stirrups of their enemy [2]. Their horses were also larger-bred by noble classes to show off their strength, not run through the deserts. In a fight were they had to track down the enemy, these horses would be more tired than the small and hardy desert horses, but in a fight where the enemy came to them the larger horses would be rested, ready-and give their riders an advantage in a charge.

Assisting this ‘heavy cavalry’ were nomads who sided with Dawn Horse against Coyote. Equally well armed as their adversaries, they protected the flanks of the Imperial Cavalry and fired projectiles while Coyote’s army charged in.

When the battle was met, it was not immediately apparent that Coyote would lose. His army was extremely large, consisting of hardened desert men who did not fear the ‘soft’ imperials. But their arrows failed to penetrate their foe’s armor, and their clubs and obsidian axes shattered on the bronze helmets of the imperials. The imperial side used their thrusting spears to devastating effect. As the battle grew more intense and horses fell, warriors met on foot. There, the ability of the imperials to use their short bronze swords in close quarters gave them a great advantage over the nomads, whose less effective clubs and axes required a great deal of arm space to wield effectively and on a crowded battlefield lost some of their edge. Perhaps against a people who fought mere skirmishes or who honored the idea of one to one combat the nomads could have obtained that space, but the Gaayu’be’ena’a did not become the Thousand Year Empire by playing fair or doing anything small.

A new invention had kept Dawn Horse’s men well supplied during their stint in the north, and now the great wagons clattered onto the battlefield delivering foot soldiers right into the heart of the fight. In addition to giving extra men to crowd the battlefield and outnumber the enemy, the wagons appeared terrifying to the nomads, who had never seen such things used before. Combined with the imperial-allied ‘light cavalry’ which kept them from enacting a pincer movement, it became clear that the would-be lord of Mishwakan had lost the day. Coyote attempted to flee, but was killed by an arrow. Dawn Horse had now succeeded were all in the Empire had failed.

Perhaps the success had gotten to his head, which may explain why he immediately marched south and beheaded his former friend 4 Spotted Deer, taking the title of Kaloomte B’alam for himself. This was the other problem of the Gaayu’be’ena’a-changing of regime through usurpation and assassination. While a strong and popular leader like Dawn Horse could ensure stability when they took over, more commonly these violent takeovers often lead to bloodshed as the usurpers faced revolts by rivals seeking to take them off the throne in turn.

At least the northern tribes had been temporarily subdued. Disturbingly, though, part of Dawn Horse’s victory depended on bribing some of the nomads. It was a dependence that would grow, with lethal consequences for the empire.

[1] Quite possibly a name given to him by the scribes to denigrate him. Like other historical 'villains' such as the legendarily incompetent amateur warlord 2 Vulture Scribe, this was a name given to their post-mortem biographies.

[2] The Columbian equivalent of the Iron Stirrup.

Share: