You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Out of the Ashes: The Byzantine Empire From Basil II To The Present

- Thread starter Vasilas

- Start date

- Status

- Not open for further replies.

@darthfanta

All jokes aside, I appreciate your level of engagement and thoughts. They make me think a lot more deeply than I normally would-so thanks!

All jokes aside, I appreciate your level of engagement and thoughts. They make me think a lot more deeply than I normally would-so thanks!

1064-1072: End of Innocence

In the Shadow of Manzikert

It is somewhat surprising that an event as deeply influential as the battle of Manzikert would be so poorly documented in immediate contemporary sources, with no surviving eyewitness accounts on the Imperial side having endured the passage of time. Emperor John in particular did not leave behind any notes on the battle that could serve as future reference- a highly unusual measure by the standards set by his immediate predecessors and successors. Nonetheless, the records in some ways reveal a lot: six strategoi were fired within a year of the battle and two were flat out executed on what appear to be the flimsiest of charges.

The secondary sources like Psellus or Skylitzes agree on very little, but some essential details about the chaotic period following Basil III’s death can be gleamed: John II accepted the surrender of the Cappadocians, the Orphans and the Normans took disproportionately fewer losses in an exceptionally bloody fight, and the battle was a near stalemate before a sudden, almost “divine” intervention orchestrated by the direct orders of the Emperor. Based on a close reading of the sources, I offer the following reconstruction of the battle, which is unlikely to be wholly incorrect.

John II was a reluctant warrior, as documented by all sources from that era. He had likely attempted to buy peace from the Turks after the rebel Mesopotamian Doux Nikepheros had been killed, hoping that they would pull out after a sufficiently large bribe. He was unfortunately not in a position to cede territory, and the young Sultan wanted concessions in Armenia from the Empire. John might have been willing to let go of Mesopotamia if the Turks were particularly obstinate, but he was quite aware that he would not survive a week if he spontaneously gave up extra territory. Being caught between the devil and the deep blue sea, John was thus left with no choice but to fight, with the two armies crossing path in close proximity of Manzikert in Armenia. Lack of military experience had caused John to pass direct command to the Domestic of Schools Constantine Diogenes, although this was not a decision welcomed by Alexios Maniakes, leader of the Orphans. Constantine however was the senior leader, having fought in Carthage in the last round of the North African war, and was a trusted pair of hands for the Empire.

Constantine however would prove to be a poor leader for the situation, as he had never faced an army as organized as that of the Turks, having only fought Berber raiding bands. He was also used to leading highly trained soldiers all his life, not green recruits that Basil III had been forced to pick up. Aware of a qualitative disparity, Constantine used the infantry as cannon fodder against the Turkish cavalry, running up massive body counts on the Imperial side as the Turks hacked their way through new recruits who nonetheless held ranks on account of a near fanatical devotion to the Empire (or Christ, if some of the Church sources are to be trusted). The Cappadocians acquitted themselves well (having been sent to the front lines as punishment for their rebellion) but they could not hold back the tide. Constantine’s hope of weakening the Turks enough for a single Cataphract strike to finish them off failed miserably as the Normans folded in an inopportune moment. The battle at this point came dangerously close to a Imperial rout despite a narrow numerical superiority that had persisted (the Empire had lost nearly two men per Turk slain, but it had fielded a much larger number of men). Emperor John by this point had given up hope in conventional warfare and took charge in this moment to ask the alchemists to take action. Basil III had long patronized their guilds in Constantinople, and had brought many of them along to assist for a potential siege of Nineveh. Their utility in pitched battle was more questionable from Constantine’s perspective and they had hereto been kept uninvolved. The worried Emperor however had limited alternatives as the situation progressively worsened, and so called upon their services.

It is almost certain that the Orphans assisted them in actually catapulting some of their mixtures, though it is unclear whether they the chemicals in question were some unstable variant of Greek fire or proto-gunpowder or something entirely different. The Official Secrets Act of the Roman Empire is extremely unwilling to share details even if they are a thousand years old, leaving the exact nature of the incendiary in doubt. I am personally unconvinced about theories about it being gunpowder (John Kallinikos had not been particularly secretive about using gunpowder in his time, though admittedly the scale of conflicts he was involved in would have made secrecy impossible), but it is not quite impossible that Constantinople had stumbled across it during the 11th century and only came clean about possessing the technology once it was clear that Chinese powder would be used against them, regardless of their choice. It is far more likely however, that it was some kind of proto-pyrophoric material (1), which my chemistry colleagues inform me was just possible to synthesize at that time, based on surviving glassware recovered. Such a mixture would be extremely fickle and prohibitively expensive (explaining relative lack of usage in the future) but could be devastatingly effective in certain situations-such as the Battle of Manzikert.

The incendiary charge succeeded in breaking Turkish ranks as horses panicked due to sudden loud series of explosions and the flying sharpnel had probably killed more than Imperial arrows had till that point. The material damage itself had not been all that great, but the temporary collapse of discipline would prove fatal for the Turks, as Maniakes led a major charge straight in and was able to reach the Sultan himself. Pope Alexander’s later account (recounting his days as Papal Apocarius [1] in Constantinople) noted that:

I asked my guest about what truly happened at Manzikert. He went silent for the longest while, making me wonder if I had overly insulted him. But he did finally speak just as I was about to move on to a different topic.

“It is shameful for the warrior in me to admit to our defeat there. But we lost, and that is truth.”

“Even the Romans admit that we were winning, and I was salivating over the thought of avenging the Mahomettans who Basileos II had conquered. Then we learned that God would never let his chosen people fall.”

“It suddenly rained fire, as massive spurts of flames burst around me, roasting several of my companions. I was barely able to control my horse before the Orphan cut his head off, but in those few moments of utter chaos, I saw the Truth and never strayed from it since.”

“The Truth?”, I asked-a little too eager to discover what could have made a Mahomettan abandon his god and seek the grace of Christ.

“Aye, I saw Him. A long and sad face, clad in dark blue robes up in the sky-with his hands stretched towards me. I reached for it as I lost consciousness, and the last thing I remember are his brown eyes,” said the former Sultan of the Turks.

“I saw those eyes again when I was at the camp and the Emperor came to meet me. His face was gentle, with only vestiges of sadness left-and I surrendered myself to him. I was a warrior raised by the sword, but I knew He was something greater than myself-someone graced by God who we mere mortals could not comprehend.”

“But, pardon me-did you not say that you saw Christ?”

“Have you seen Emperor John in front of the great mosaics of Constantinople? I do not know if I saw the Son or His Viceregent-but I knew that I would serve them both till my dying day.”

Alexander’s account was highly dramatized and perhaps twisted to highlight similarities with Constantine at the Milvan bridge, but there was no doubt that Sultan Alp Arslan had experienced a Road to Damascus moment in the fields of Manzikert. It would however take a while longer for most observers to realize that his road to Christ was not quite consistent with Nicene-Chalcedonian traditions, but it was far too late by then to alter doctrine of the Turkish Church (at least, without a major schism) he founded and geopolitics would ensure that his theological heirs would endure long, grudgingly tolerated by more conventional Christian states as the alternative was far more problematic. Both Orthodox and Marcionist found the veneration of the very mortal Emperor John II as a pseudo-divine figure to be a bitter pill to swallow, but they vastly preferred heretics who nonetheless accepted Jesus Christ as God’s son and savior of mankind to those who denied Christ’s divinity. The Turkish Christians on their part were too thoroughly despised for apostasy by their Islamic brethren to have an alternative to supporting major Christian powers. This did not however stop Latin Churchmen from grumbling about this disastrous heresy that was perhaps a better fit for pagan Rome than the Christian era, and use it as an example to challenge the authority of the Constantinopolitan Emperor.

The Greek accounts unsurprisingly try to shift the blame for the theological controversy to Alp Arslan himself, since they theologically agreed with the Latins and were embarrassed by the excessive veneration of an Emperor. John Skylitzes claims that the Sultan was dragged half unconscious before Emperor John after the battle, but the Emperor angrily demanded that medical attention be first given to such a valuable hostage. The Sultan was brought before the Emperor after he had suitably recovered, and was asked what would have happened if the positions of the two men were reversed. Alp Arslan had apparently stated (with no small measure of contrition) that he’d have the Emperor flogged, and then have burnt alive in Baghdad (no doubt a grisly throwback to the murder of the last Abbasid Caliph by Basil II). The Emperor had ostensibly replied:

“But I will not imitate you. Christ teaches gentleness and forgiveness of past sins. He resists the proud and gives grace to the humble. Too much blood have been split here today, and I would like no more be wasted. I will let you return back to your camp if you would swear on your God that you will never trouble the Empire of the Romans again.”

At this point the Sultan had apparently broken down and fell on the feet of the Emperor, crying that he hereto worshiped a false God he could no longer swear upon and begged the Emperor to teach him about this Great and kind God of his. The Emperor tried his best as they journeyed back to Constantinople, but the Sultan was too simple a man to grasp the complexity of Christology and came to view the Emperor as a god, acknowledging Christ only as a superior God since his own divine patron treated him as a greater being. A contemptuous man, he refused the counsel of learned men who he saw as of lower birth, but clung onto the Emperor who did not have the time to recognize and correct the dangerous flaws in his pupil’s education.

Neither of these accounts are particularly believable (2)-especially since John II could hardly afford to let such an extremely valuable prisoner walk free after such a hard fought battle. Arslan’s conversion was viewed to be genuine was almost everyone, since Pope Alexander noted that he refused to leave Constantinople even when his son offered a massive ransom after three months, choosing instead to learn more about his new faith (or the magic which the Emperor had used to defeat him, as cynics have often noted). The extent to which he truly considered John II to be a supernatural entity is quite unknown, as his writings are no longer extant and he might have been attempting to flatter and praise his benefactor to outsiders like Alexander. It may also be that he was truly touched by the kindness of a man he had grown up thinking as the devil and sought to be loyal to him without fully comprehending the alternate interpretations of his actions. Whatever the actual sequence of events, Alp Arslan became a committed Christian through conversations with the Emperor on the journey back to Constantinople, and was baptized as Leo[2] in Hagia Sophia on the first anniversary of the battle. Five thousand Turks taken captive in Manzikert followed their Sultan in this, becoming the core of Turkish Christianity. It was a homecoming on some levels-Seljuk himself was likely Nestorian before embracing Islam barely a century before this moment[3], and quite a few priests thought that their brethren beyond the Empire would soon follow suit. It was a foolish hope that did not take into account the almost magical appeal Islam has over nomadic people, and it did not come to pass. Turkish Christianity nonetheless became an entity worth considering over the century to come, through blood spent by others for its cause.

John had far too few men left at Manzikert to actually chase the Turks out of Mesopotamia. This task was left to the Normans, as their leader William was elevated to be Doux Mesopotamiae (hereditary) and charged with bringing the province back under control. Nineveh quickly fell before the Normans, but they were unable to proceed much further south, being localized to the old northern Mesopotamian region. Alp Arslan's eldest son was now Sultan, and his advisors were capable of organizing a strong enough defense for the south. It would not have lasted against Basil II’s army-but the scarred Emperor John chose to retreat and lick his wounds, than risk another potentially catastrophic confrontation as Manzikert. The Normans were thus mostly on their own, which suited them just fine as well. John had consented to recruiting from their homeland in the defense of the Mesopotamian frontier, and many were lured in by the promise of land. The trickle slowed after the Norman conquest of Albion which opened up closer lands, but the wealth of Mesopotamia acted as a magnet for ambitious men in Latin Europe, hereto mostly unaffected by the Empire’s eastern expansion.

John however did not wish to continue on with mercenaries long term. He had recognized that the weakening of the army under Basil III to be a blunder, and devoted himself to fixing that. Constantine Diogenes was executed for a supposed attempted coup, but it is far more likely that the Emperor had him eliminated out of spite (sources are unanimous in stating “Emperor John never forgave Diogenes for the lives lost at Manzikert”). The Domestic of the East followed his boss to the grave as well, and all the Anatolian strategoi were replaced within a year with people who had experience Manzikert and had distinguished themselves there. John went as far to declare that “eternal war is in the interest of the state, as it prevents the generals from going rusty and allows only the fittest to remain”. Sufficiently many middle rank officers had done well individually at Manzikert to allow John to fill critical posts.

The army had bigger problems than leadership alone, as recruitment had been plummeting over the years. Emperor John attempted to fix this by ending the policy of land grants in Egypt for civilians, thereby ending the population transfer from Anatolia to Egypt. Anatolia had long been used as a population reserve to hellenize massively depopulated provinces, but the population of the plateau (especially in the sparsely settled center and east) had suffered far too much for it. John also cut the head tax throughout the Empire to stop Egypt’s natural population from shrinking without immigration, and to encourage reproduction in the core territories. Settling outside the borders was discouraged, and slavs were offered significantly larger plots if they were willing to move to the Anatolia-Mesopotamia frontier. John also demanded that each theme be ready to supply at least 15000 men for war and increased the tagma to Basil II levels. He also charged Alexios Maniakes with developing a new training program for recruits, which had to contain exercise and actual war games for practice. Expenditure on the Alchemist guild was doubled within a year of Manzikert, which unfortunately came at the expense of the University (the Emperor famously telling them to have less Professors of Greek and Latin and more Mathematicians for war). He also trebled the budget for the Red Sea navy (seeing it as a way to strike Mesopotamia from the south in a future war) and attempted to bring it to par with the Eastern Mediterranean fleet. John II thus started the process of rearmament that would define the latter half of the eleventh century for the Empire, though he did not ultimately live to see the fruits of his labors.

And the Emperor had indeed labored! He claimed to have slept no more than three hours a night, a figure corroborated by Psellos who claimed the Emperor worked like an ass. He also spent like a drunken sailor, seeing the surplus of previous years as a convenient way to compensate for military weakness. The Empire would have gone into debt with his spending spree if it was not more large tax hikes on trade, and on richer families (introducing what remarkably seemed like a progressive tax policy). Even then it was a near thing, and complaints were very common. The militarists were also unhappy with the Emperor refusing to endorse offensive war. By 1071 the Empire was almost back to its peak strength and there were calls to finally put an end to the Turkish Emirate in Mesopotamia. Arslan’s eldest had proven too independent for his advisors and had been replaced in favor of a younger brother in 1070, and the Normans were reporting back that the Turks were splintering into factions-to an extent where Doux William suspected one final heave would finish them once and for all. John mistrusted those reports, believing William merely wanted to gain lands in exchange for Greek blood (which was indeed the case as the Doux intentionally exaggerated Turkish weakness, a fact that became clear later), but the military upper ranks disagreed. They found a champion in the young co-Emperor George, who was fiercely advocating for a Mesopotamian war (egged on by his close friend Robert, William’s son). John nonetheless proved to be an immovable wall, and he still had considerable support amidst the common people who wanted to be spared another war far from their homes. He merely consented to signing off on naval raids in the Persian Gulf by the Egyptian navy, and that too with extreme caution (perhaps hoping that the Turks would get the message and finish William).

The former Alp Arslan however proved to be a problem. Worried about his children (the eldest’s end had not been pleasant) and perhaps desiring a crown once more, he begged the Emperor for support. John ignored him like he had ignored others, brusquely stating the Empire will not be ready for war for another twenty years and believing that would be the end of it. Undeterred, Leo went to pilgrimage in Rome, where Pope Alexander had recently come into office, after a successful career as Apocarius. Leo called upon the Pope to assist him in securing the East for Christendom, claiming that the “Most August Empire of the Romans had been too fatally weakened” by Manzikert. It is unclear if Alexander was motivated more by the thought of saving Saracen souls or leaving a mark in history, but he called for a Synod in Clermont in November 1071.

The rest as they say, is history. The Pope gave a call for a Crusade to conquer the souls of the East for Christendom, which found a fertile audience in Western Europe exposed to stories of fabulous Greek conquests in the East for almost a century. There was a feeling in the West that they had not been able to match the glory of the East, and Pope Alexander’s appeal to the West to finally do its part for Christendom when the East was temporarily weak (after all the sacrifices Basil II had made to recover Jerusalem) found eager ears. The news however was met with shock and horror in Constantinople. John II flew into a rage after hearing about the call for Holy War, and was barely restrained from sending an order to the Strategos of Naples to arrest the Pope. He was talked out of it by a series of long meetings with all his chief advisors, who told him that this would mean the loss of the West after the effort invested by his forefathers to secure it, and finally relented after a day. He nonetheless personally told the Apocarius that no Latin army would be allowed on Imperial lands, and adventuring be better constrained to Spain. He further called for a Synod in Constantinople to oppose the Synod of Clermont, and affirm that Holy War was absolutely unacceptable. His private writings from the period show a great deal of turmoil over the idea, since he refused to accept the idea of a Christian jihad, declaring the idea to be antithetical to all that Christ had preached. “I no longer believe that we worship the same God,” he wrote in his journal early 1072, “and I see a great deal of truth in what Marcion of Sinope [3] had said-only the Demiurge could endorse this bloodbath”.

The journal was private and only opened for access centuries after his death. Public knowledge of such heretical thoughts would have resulted in his removal despite all other qualities, and he was wise to keep it quiet. Nonetheless, Marcionism would be his ultimate downfall-for he refused to militarily intervene against Bogomil heretics in the Balkans. He was willing to fund more Orthodox missionaries in the region, but was not going to “tell another how to find Christ at swordpoint”. This finally alienated his closest supporters, who now started to suspect if the Emperor was too scarred by Manzikert to ever sign off to another war. Alexios Maniakes in particular noted that “John turned out to be an appeaser like his father. One gutted the army, and the other would not let it act.” The knives were coming out, and one would have found the Emperor soon.

Perhaps a metaphorical one did indeed strike him, for the Emperor was unable to sleep during the week of Easter in 1072. His physician had long noted that he was far too thin to be healthy, and his hair had turned white long before his time, but complete insomnia was new. The Emperor however still kept on working, and insisted on leading the Sunday Mass when it came. He collapsed halfway through it, never to rise again. The official account stated that his heart had given out the same way as his father’s had, but the medical history of his family makes this theory suspect. He was more likely helped to his end via poisons that did not kill him but merely weakened him or prevented him from sleep, letting his constitution and exhaustion handle the rest.

Ioannes II lasted only eight years in power, unlike his immediate ancestors who had much longer reigns. His short reign nonetheless was momentous, with him starting the process of rearmament and creating the circumstances for the First Crusade. He was an uncommonly decent individual and a committed pacifist, who however refused to bury his head in sand and executed the duties of his office to the fullest extent of his ability. His influence is not so direct as that of the great Emperors, but it proved long lasting and can be seen even today in Turkish rite Churches. Perhaps more importantly, the critical support he offered to Gnostic sects had enabled their long term survival and revival in the future. This was perhaps a lot more than what anyone could have expected at the moment of his death, with his successor Giorgios I overturning the Synod of Constantinople, inviting the Crusaders to Mesopotamia and promising to fight heresy. None of that however could completely overturn his legacy, for he had understood society far better than his militarist successors ever could and thus they failed to end his legacy. John represented the end of the Age of Innocence for the Empire, enjoying the dividends of the post Arab peace. It would no longer remain bottled up in the Eastern Mediterranean and be an active participant in world affairs-in no small part because of the investments he had made. Credit must also be given for helping stave off a defeat at Manzikert, which would have opened up vast depopulated swathes of Central and Eastern Anatolia to Turkish occupation, from where the herders would have only been removed through great difficulty (if ever). A simple Orthodox Church stands today in the site of the battle, where a small prayer is led on his birthday each year:

“Ioannes of Constantinople-son of the Empire, servant of Christ.

A man gentle, generous and kind-who died for his Empire.

May the Lord have mercy on his soul.”

Few of tourists realize that this is addressed to an Emperor and not some brave local soldier. But this humble commemoration is consistent what we know about John’s life. None questioned John the Pious’ commitment to Christ, and it would do us well to remember him today when people kill others over faith. If a deeply pious medieval Christian could take a principled stance against holy war nearly a thousand years ago, why must modern man continue to butcher others in the name of faith?

Notes:

[1] Papal legate to Constantinople. The Alexander in question later became Pope (as noted in the chapter) and wrote History of the Roman Empire - the standard text concerning the Latin Empire (Principate and Dominate) which runs from Augustus to Phocas. This work of scholarship took much effort, and extensive perusal of documents in Constantinople and is the only material that preserves contents of major Latin writers whose works were burned by John Callinicus.

[2] Alp Arslan means "Heroic Lion" in Turkish. Leo was thus the obvious choice for a baptismal name.

[3] Seljuk had only converted to Islam in 985, and he had sons called Michael and Israel, suggesting a Nestorian past.

Vasilas' Notes:

(1) Nope, it was gunpowder. The reason they are unwilling to admit that is because they stole the recipe from China (like Justinian and Silkworms, but here is was just a quick Greek note no one could read). Professor Andronikos Doukas (who had accompanied the Fatimid embassy to China right before Dawd's coup and had only returned when Egypt was under the Empire) had been very busy in his time at the East. He did not get the recipe at the time, but saw some of it in action and was in any case convinced that stealing tech from China was in the best interest of the Empire. The distance makes things difficult (the lost last voyage of Basil II being a big example of some issues) but Basil III's interest in trade as well as co-opting Arab sailors knowledge about routes led to a small permanent mission in Guangzhou by 1040s. An enterprising alchemist who travelled with a mission at this time was lucky enough to learn what exactly the "fire lances" were using and immediately jumped on the next ships back (with extensive coded notes in Greek in case he did not make it). The classic secret protocol (as followed with Greek fire) resulted, and they barely had working prototypes (basically barrels and wicks) going in time for Manzikert. Gunpowder would however only be openly used once it became clear that power/s threatening the Empire also had Chinese powder and so secrecy was more hindrance than help.

They don't quite want to come clean as they have insisted for centuries that they invented it independently (later, but nonetheless without any Chinese influence). Several people they have used to make that claim (who in most cases did not know any better, as they didn't dig eleventh century secret records) are too highly regarded in society (a couple of Emperors, a few bigshot scientists etc) for the prideful Empire to come clean about the lies. Societies are often proud to the point of irrationality, and a surviving Romania is going to be an extreme case because of its history. There is also the precedent of Greek fire, and so most people do believe the claim to be a real one.

(2) Skylitzes came to the truth nonetheless. Alp Arslan converted because of the kindness of Emperor John. He simply could not believe that such a person could have led his Empire to victory, or indeed last as Emperor in the violent world-not unless he had friends in high places, such as whatever power that defeated the Turks at Manzikert.

(3) Marcionism and other Gnosticism: John II was increasingly being convinced that the Old Testament God could not be the same one as the New Testament one. One preached forgiveness and the other was a genocidal psycho so to say, and he was clear about which one he backed. By the end, he saw the Islamic/Judaic God as a malovolent entity enticing humans astray (the Demiurge-lord of the material world), while the Christian God's fundamental message was salvation-though the Church was corrupted by the Demiurge itself. He was however not loony enough to actually say this openly or act in a manner that would suggest he thought this way. That being said, he also refused to go to the other end and persecute other gnostics like the Paulicans/Bogomils, leading to his eventual downfall (yep, he was poisoned off).

John is not an actual Cathar/Bogomil/Paulican though-just to be clear. He would identify as a Marcionist in the modern era. That being said, his ideas did not develop in a vacuum but owed quite a bit to the intesting neo-Gnostic ideas floating around in Roman society's fringes at that time.

The wikipedia article on Marcionism may be of help if anyone wants to have a quick look at this: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marcionism

It is somewhat surprising that an event as deeply influential as the battle of Manzikert would be so poorly documented in immediate contemporary sources, with no surviving eyewitness accounts on the Imperial side having endured the passage of time. Emperor John in particular did not leave behind any notes on the battle that could serve as future reference- a highly unusual measure by the standards set by his immediate predecessors and successors. Nonetheless, the records in some ways reveal a lot: six strategoi were fired within a year of the battle and two were flat out executed on what appear to be the flimsiest of charges.

The secondary sources like Psellus or Skylitzes agree on very little, but some essential details about the chaotic period following Basil III’s death can be gleamed: John II accepted the surrender of the Cappadocians, the Orphans and the Normans took disproportionately fewer losses in an exceptionally bloody fight, and the battle was a near stalemate before a sudden, almost “divine” intervention orchestrated by the direct orders of the Emperor. Based on a close reading of the sources, I offer the following reconstruction of the battle, which is unlikely to be wholly incorrect.

John II was a reluctant warrior, as documented by all sources from that era. He had likely attempted to buy peace from the Turks after the rebel Mesopotamian Doux Nikepheros had been killed, hoping that they would pull out after a sufficiently large bribe. He was unfortunately not in a position to cede territory, and the young Sultan wanted concessions in Armenia from the Empire. John might have been willing to let go of Mesopotamia if the Turks were particularly obstinate, but he was quite aware that he would not survive a week if he spontaneously gave up extra territory. Being caught between the devil and the deep blue sea, John was thus left with no choice but to fight, with the two armies crossing path in close proximity of Manzikert in Armenia. Lack of military experience had caused John to pass direct command to the Domestic of Schools Constantine Diogenes, although this was not a decision welcomed by Alexios Maniakes, leader of the Orphans. Constantine however was the senior leader, having fought in Carthage in the last round of the North African war, and was a trusted pair of hands for the Empire.

Constantine however would prove to be a poor leader for the situation, as he had never faced an army as organized as that of the Turks, having only fought Berber raiding bands. He was also used to leading highly trained soldiers all his life, not green recruits that Basil III had been forced to pick up. Aware of a qualitative disparity, Constantine used the infantry as cannon fodder against the Turkish cavalry, running up massive body counts on the Imperial side as the Turks hacked their way through new recruits who nonetheless held ranks on account of a near fanatical devotion to the Empire (or Christ, if some of the Church sources are to be trusted). The Cappadocians acquitted themselves well (having been sent to the front lines as punishment for their rebellion) but they could not hold back the tide. Constantine’s hope of weakening the Turks enough for a single Cataphract strike to finish them off failed miserably as the Normans folded in an inopportune moment. The battle at this point came dangerously close to a Imperial rout despite a narrow numerical superiority that had persisted (the Empire had lost nearly two men per Turk slain, but it had fielded a much larger number of men). Emperor John by this point had given up hope in conventional warfare and took charge in this moment to ask the alchemists to take action. Basil III had long patronized their guilds in Constantinople, and had brought many of them along to assist for a potential siege of Nineveh. Their utility in pitched battle was more questionable from Constantine’s perspective and they had hereto been kept uninvolved. The worried Emperor however had limited alternatives as the situation progressively worsened, and so called upon their services.

It is almost certain that the Orphans assisted them in actually catapulting some of their mixtures, though it is unclear whether they the chemicals in question were some unstable variant of Greek fire or proto-gunpowder or something entirely different. The Official Secrets Act of the Roman Empire is extremely unwilling to share details even if they are a thousand years old, leaving the exact nature of the incendiary in doubt. I am personally unconvinced about theories about it being gunpowder (John Kallinikos had not been particularly secretive about using gunpowder in his time, though admittedly the scale of conflicts he was involved in would have made secrecy impossible), but it is not quite impossible that Constantinople had stumbled across it during the 11th century and only came clean about possessing the technology once it was clear that Chinese powder would be used against them, regardless of their choice. It is far more likely however, that it was some kind of proto-pyrophoric material (1), which my chemistry colleagues inform me was just possible to synthesize at that time, based on surviving glassware recovered. Such a mixture would be extremely fickle and prohibitively expensive (explaining relative lack of usage in the future) but could be devastatingly effective in certain situations-such as the Battle of Manzikert.

The incendiary charge succeeded in breaking Turkish ranks as horses panicked due to sudden loud series of explosions and the flying sharpnel had probably killed more than Imperial arrows had till that point. The material damage itself had not been all that great, but the temporary collapse of discipline would prove fatal for the Turks, as Maniakes led a major charge straight in and was able to reach the Sultan himself. Pope Alexander’s later account (recounting his days as Papal Apocarius [1] in Constantinople) noted that:

I asked my guest about what truly happened at Manzikert. He went silent for the longest while, making me wonder if I had overly insulted him. But he did finally speak just as I was about to move on to a different topic.

“It is shameful for the warrior in me to admit to our defeat there. But we lost, and that is truth.”

“Even the Romans admit that we were winning, and I was salivating over the thought of avenging the Mahomettans who Basileos II had conquered. Then we learned that God would never let his chosen people fall.”

“It suddenly rained fire, as massive spurts of flames burst around me, roasting several of my companions. I was barely able to control my horse before the Orphan cut his head off, but in those few moments of utter chaos, I saw the Truth and never strayed from it since.”

“The Truth?”, I asked-a little too eager to discover what could have made a Mahomettan abandon his god and seek the grace of Christ.

“Aye, I saw Him. A long and sad face, clad in dark blue robes up in the sky-with his hands stretched towards me. I reached for it as I lost consciousness, and the last thing I remember are his brown eyes,” said the former Sultan of the Turks.

“I saw those eyes again when I was at the camp and the Emperor came to meet me. His face was gentle, with only vestiges of sadness left-and I surrendered myself to him. I was a warrior raised by the sword, but I knew He was something greater than myself-someone graced by God who we mere mortals could not comprehend.”

“But, pardon me-did you not say that you saw Christ?”

“Have you seen Emperor John in front of the great mosaics of Constantinople? I do not know if I saw the Son or His Viceregent-but I knew that I would serve them both till my dying day.”

Alexander’s account was highly dramatized and perhaps twisted to highlight similarities with Constantine at the Milvan bridge, but there was no doubt that Sultan Alp Arslan had experienced a Road to Damascus moment in the fields of Manzikert. It would however take a while longer for most observers to realize that his road to Christ was not quite consistent with Nicene-Chalcedonian traditions, but it was far too late by then to alter doctrine of the Turkish Church (at least, without a major schism) he founded and geopolitics would ensure that his theological heirs would endure long, grudgingly tolerated by more conventional Christian states as the alternative was far more problematic. Both Orthodox and Marcionist found the veneration of the very mortal Emperor John II as a pseudo-divine figure to be a bitter pill to swallow, but they vastly preferred heretics who nonetheless accepted Jesus Christ as God’s son and savior of mankind to those who denied Christ’s divinity. The Turkish Christians on their part were too thoroughly despised for apostasy by their Islamic brethren to have an alternative to supporting major Christian powers. This did not however stop Latin Churchmen from grumbling about this disastrous heresy that was perhaps a better fit for pagan Rome than the Christian era, and use it as an example to challenge the authority of the Constantinopolitan Emperor.

The Greek accounts unsurprisingly try to shift the blame for the theological controversy to Alp Arslan himself, since they theologically agreed with the Latins and were embarrassed by the excessive veneration of an Emperor. John Skylitzes claims that the Sultan was dragged half unconscious before Emperor John after the battle, but the Emperor angrily demanded that medical attention be first given to such a valuable hostage. The Sultan was brought before the Emperor after he had suitably recovered, and was asked what would have happened if the positions of the two men were reversed. Alp Arslan had apparently stated (with no small measure of contrition) that he’d have the Emperor flogged, and then have burnt alive in Baghdad (no doubt a grisly throwback to the murder of the last Abbasid Caliph by Basil II). The Emperor had ostensibly replied:

“But I will not imitate you. Christ teaches gentleness and forgiveness of past sins. He resists the proud and gives grace to the humble. Too much blood have been split here today, and I would like no more be wasted. I will let you return back to your camp if you would swear on your God that you will never trouble the Empire of the Romans again.”

At this point the Sultan had apparently broken down and fell on the feet of the Emperor, crying that he hereto worshiped a false God he could no longer swear upon and begged the Emperor to teach him about this Great and kind God of his. The Emperor tried his best as they journeyed back to Constantinople, but the Sultan was too simple a man to grasp the complexity of Christology and came to view the Emperor as a god, acknowledging Christ only as a superior God since his own divine patron treated him as a greater being. A contemptuous man, he refused the counsel of learned men who he saw as of lower birth, but clung onto the Emperor who did not have the time to recognize and correct the dangerous flaws in his pupil’s education.

Neither of these accounts are particularly believable (2)-especially since John II could hardly afford to let such an extremely valuable prisoner walk free after such a hard fought battle. Arslan’s conversion was viewed to be genuine was almost everyone, since Pope Alexander noted that he refused to leave Constantinople even when his son offered a massive ransom after three months, choosing instead to learn more about his new faith (or the magic which the Emperor had used to defeat him, as cynics have often noted). The extent to which he truly considered John II to be a supernatural entity is quite unknown, as his writings are no longer extant and he might have been attempting to flatter and praise his benefactor to outsiders like Alexander. It may also be that he was truly touched by the kindness of a man he had grown up thinking as the devil and sought to be loyal to him without fully comprehending the alternate interpretations of his actions. Whatever the actual sequence of events, Alp Arslan became a committed Christian through conversations with the Emperor on the journey back to Constantinople, and was baptized as Leo[2] in Hagia Sophia on the first anniversary of the battle. Five thousand Turks taken captive in Manzikert followed their Sultan in this, becoming the core of Turkish Christianity. It was a homecoming on some levels-Seljuk himself was likely Nestorian before embracing Islam barely a century before this moment[3], and quite a few priests thought that their brethren beyond the Empire would soon follow suit. It was a foolish hope that did not take into account the almost magical appeal Islam has over nomadic people, and it did not come to pass. Turkish Christianity nonetheless became an entity worth considering over the century to come, through blood spent by others for its cause.

John had far too few men left at Manzikert to actually chase the Turks out of Mesopotamia. This task was left to the Normans, as their leader William was elevated to be Doux Mesopotamiae (hereditary) and charged with bringing the province back under control. Nineveh quickly fell before the Normans, but they were unable to proceed much further south, being localized to the old northern Mesopotamian region. Alp Arslan's eldest son was now Sultan, and his advisors were capable of organizing a strong enough defense for the south. It would not have lasted against Basil II’s army-but the scarred Emperor John chose to retreat and lick his wounds, than risk another potentially catastrophic confrontation as Manzikert. The Normans were thus mostly on their own, which suited them just fine as well. John had consented to recruiting from their homeland in the defense of the Mesopotamian frontier, and many were lured in by the promise of land. The trickle slowed after the Norman conquest of Albion which opened up closer lands, but the wealth of Mesopotamia acted as a magnet for ambitious men in Latin Europe, hereto mostly unaffected by the Empire’s eastern expansion.

John however did not wish to continue on with mercenaries long term. He had recognized that the weakening of the army under Basil III to be a blunder, and devoted himself to fixing that. Constantine Diogenes was executed for a supposed attempted coup, but it is far more likely that the Emperor had him eliminated out of spite (sources are unanimous in stating “Emperor John never forgave Diogenes for the lives lost at Manzikert”). The Domestic of the East followed his boss to the grave as well, and all the Anatolian strategoi were replaced within a year with people who had experience Manzikert and had distinguished themselves there. John went as far to declare that “eternal war is in the interest of the state, as it prevents the generals from going rusty and allows only the fittest to remain”. Sufficiently many middle rank officers had done well individually at Manzikert to allow John to fill critical posts.

The army had bigger problems than leadership alone, as recruitment had been plummeting over the years. Emperor John attempted to fix this by ending the policy of land grants in Egypt for civilians, thereby ending the population transfer from Anatolia to Egypt. Anatolia had long been used as a population reserve to hellenize massively depopulated provinces, but the population of the plateau (especially in the sparsely settled center and east) had suffered far too much for it. John also cut the head tax throughout the Empire to stop Egypt’s natural population from shrinking without immigration, and to encourage reproduction in the core territories. Settling outside the borders was discouraged, and slavs were offered significantly larger plots if they were willing to move to the Anatolia-Mesopotamia frontier. John also demanded that each theme be ready to supply at least 15000 men for war and increased the tagma to Basil II levels. He also charged Alexios Maniakes with developing a new training program for recruits, which had to contain exercise and actual war games for practice. Expenditure on the Alchemist guild was doubled within a year of Manzikert, which unfortunately came at the expense of the University (the Emperor famously telling them to have less Professors of Greek and Latin and more Mathematicians for war). He also trebled the budget for the Red Sea navy (seeing it as a way to strike Mesopotamia from the south in a future war) and attempted to bring it to par with the Eastern Mediterranean fleet. John II thus started the process of rearmament that would define the latter half of the eleventh century for the Empire, though he did not ultimately live to see the fruits of his labors.

And the Emperor had indeed labored! He claimed to have slept no more than three hours a night, a figure corroborated by Psellos who claimed the Emperor worked like an ass. He also spent like a drunken sailor, seeing the surplus of previous years as a convenient way to compensate for military weakness. The Empire would have gone into debt with his spending spree if it was not more large tax hikes on trade, and on richer families (introducing what remarkably seemed like a progressive tax policy). Even then it was a near thing, and complaints were very common. The militarists were also unhappy with the Emperor refusing to endorse offensive war. By 1071 the Empire was almost back to its peak strength and there were calls to finally put an end to the Turkish Emirate in Mesopotamia. Arslan’s eldest had proven too independent for his advisors and had been replaced in favor of a younger brother in 1070, and the Normans were reporting back that the Turks were splintering into factions-to an extent where Doux William suspected one final heave would finish them once and for all. John mistrusted those reports, believing William merely wanted to gain lands in exchange for Greek blood (which was indeed the case as the Doux intentionally exaggerated Turkish weakness, a fact that became clear later), but the military upper ranks disagreed. They found a champion in the young co-Emperor George, who was fiercely advocating for a Mesopotamian war (egged on by his close friend Robert, William’s son). John nonetheless proved to be an immovable wall, and he still had considerable support amidst the common people who wanted to be spared another war far from their homes. He merely consented to signing off on naval raids in the Persian Gulf by the Egyptian navy, and that too with extreme caution (perhaps hoping that the Turks would get the message and finish William).

The former Alp Arslan however proved to be a problem. Worried about his children (the eldest’s end had not been pleasant) and perhaps desiring a crown once more, he begged the Emperor for support. John ignored him like he had ignored others, brusquely stating the Empire will not be ready for war for another twenty years and believing that would be the end of it. Undeterred, Leo went to pilgrimage in Rome, where Pope Alexander had recently come into office, after a successful career as Apocarius. Leo called upon the Pope to assist him in securing the East for Christendom, claiming that the “Most August Empire of the Romans had been too fatally weakened” by Manzikert. It is unclear if Alexander was motivated more by the thought of saving Saracen souls or leaving a mark in history, but he called for a Synod in Clermont in November 1071.

The rest as they say, is history. The Pope gave a call for a Crusade to conquer the souls of the East for Christendom, which found a fertile audience in Western Europe exposed to stories of fabulous Greek conquests in the East for almost a century. There was a feeling in the West that they had not been able to match the glory of the East, and Pope Alexander’s appeal to the West to finally do its part for Christendom when the East was temporarily weak (after all the sacrifices Basil II had made to recover Jerusalem) found eager ears. The news however was met with shock and horror in Constantinople. John II flew into a rage after hearing about the call for Holy War, and was barely restrained from sending an order to the Strategos of Naples to arrest the Pope. He was talked out of it by a series of long meetings with all his chief advisors, who told him that this would mean the loss of the West after the effort invested by his forefathers to secure it, and finally relented after a day. He nonetheless personally told the Apocarius that no Latin army would be allowed on Imperial lands, and adventuring be better constrained to Spain. He further called for a Synod in Constantinople to oppose the Synod of Clermont, and affirm that Holy War was absolutely unacceptable. His private writings from the period show a great deal of turmoil over the idea, since he refused to accept the idea of a Christian jihad, declaring the idea to be antithetical to all that Christ had preached. “I no longer believe that we worship the same God,” he wrote in his journal early 1072, “and I see a great deal of truth in what Marcion of Sinope [3] had said-only the Demiurge could endorse this bloodbath”.

The journal was private and only opened for access centuries after his death. Public knowledge of such heretical thoughts would have resulted in his removal despite all other qualities, and he was wise to keep it quiet. Nonetheless, Marcionism would be his ultimate downfall-for he refused to militarily intervene against Bogomil heretics in the Balkans. He was willing to fund more Orthodox missionaries in the region, but was not going to “tell another how to find Christ at swordpoint”. This finally alienated his closest supporters, who now started to suspect if the Emperor was too scarred by Manzikert to ever sign off to another war. Alexios Maniakes in particular noted that “John turned out to be an appeaser like his father. One gutted the army, and the other would not let it act.” The knives were coming out, and one would have found the Emperor soon.

Perhaps a metaphorical one did indeed strike him, for the Emperor was unable to sleep during the week of Easter in 1072. His physician had long noted that he was far too thin to be healthy, and his hair had turned white long before his time, but complete insomnia was new. The Emperor however still kept on working, and insisted on leading the Sunday Mass when it came. He collapsed halfway through it, never to rise again. The official account stated that his heart had given out the same way as his father’s had, but the medical history of his family makes this theory suspect. He was more likely helped to his end via poisons that did not kill him but merely weakened him or prevented him from sleep, letting his constitution and exhaustion handle the rest.

Ioannes II lasted only eight years in power, unlike his immediate ancestors who had much longer reigns. His short reign nonetheless was momentous, with him starting the process of rearmament and creating the circumstances for the First Crusade. He was an uncommonly decent individual and a committed pacifist, who however refused to bury his head in sand and executed the duties of his office to the fullest extent of his ability. His influence is not so direct as that of the great Emperors, but it proved long lasting and can be seen even today in Turkish rite Churches. Perhaps more importantly, the critical support he offered to Gnostic sects had enabled their long term survival and revival in the future. This was perhaps a lot more than what anyone could have expected at the moment of his death, with his successor Giorgios I overturning the Synod of Constantinople, inviting the Crusaders to Mesopotamia and promising to fight heresy. None of that however could completely overturn his legacy, for he had understood society far better than his militarist successors ever could and thus they failed to end his legacy. John represented the end of the Age of Innocence for the Empire, enjoying the dividends of the post Arab peace. It would no longer remain bottled up in the Eastern Mediterranean and be an active participant in world affairs-in no small part because of the investments he had made. Credit must also be given for helping stave off a defeat at Manzikert, which would have opened up vast depopulated swathes of Central and Eastern Anatolia to Turkish occupation, from where the herders would have only been removed through great difficulty (if ever). A simple Orthodox Church stands today in the site of the battle, where a small prayer is led on his birthday each year:

“Ioannes of Constantinople-son of the Empire, servant of Christ.

A man gentle, generous and kind-who died for his Empire.

May the Lord have mercy on his soul.”

Few of tourists realize that this is addressed to an Emperor and not some brave local soldier. But this humble commemoration is consistent what we know about John’s life. None questioned John the Pious’ commitment to Christ, and it would do us well to remember him today when people kill others over faith. If a deeply pious medieval Christian could take a principled stance against holy war nearly a thousand years ago, why must modern man continue to butcher others in the name of faith?

Notes:

[1] Papal legate to Constantinople. The Alexander in question later became Pope (as noted in the chapter) and wrote History of the Roman Empire - the standard text concerning the Latin Empire (Principate and Dominate) which runs from Augustus to Phocas. This work of scholarship took much effort, and extensive perusal of documents in Constantinople and is the only material that preserves contents of major Latin writers whose works were burned by John Callinicus.

[2] Alp Arslan means "Heroic Lion" in Turkish. Leo was thus the obvious choice for a baptismal name.

[3] Seljuk had only converted to Islam in 985, and he had sons called Michael and Israel, suggesting a Nestorian past.

Vasilas' Notes:

(1) Nope, it was gunpowder. The reason they are unwilling to admit that is because they stole the recipe from China (like Justinian and Silkworms, but here is was just a quick Greek note no one could read). Professor Andronikos Doukas (who had accompanied the Fatimid embassy to China right before Dawd's coup and had only returned when Egypt was under the Empire) had been very busy in his time at the East. He did not get the recipe at the time, but saw some of it in action and was in any case convinced that stealing tech from China was in the best interest of the Empire. The distance makes things difficult (the lost last voyage of Basil II being a big example of some issues) but Basil III's interest in trade as well as co-opting Arab sailors knowledge about routes led to a small permanent mission in Guangzhou by 1040s. An enterprising alchemist who travelled with a mission at this time was lucky enough to learn what exactly the "fire lances" were using and immediately jumped on the next ships back (with extensive coded notes in Greek in case he did not make it). The classic secret protocol (as followed with Greek fire) resulted, and they barely had working prototypes (basically barrels and wicks) going in time for Manzikert. Gunpowder would however only be openly used once it became clear that power/s threatening the Empire also had Chinese powder and so secrecy was more hindrance than help.

They don't quite want to come clean as they have insisted for centuries that they invented it independently (later, but nonetheless without any Chinese influence). Several people they have used to make that claim (who in most cases did not know any better, as they didn't dig eleventh century secret records) are too highly regarded in society (a couple of Emperors, a few bigshot scientists etc) for the prideful Empire to come clean about the lies. Societies are often proud to the point of irrationality, and a surviving Romania is going to be an extreme case because of its history. There is also the precedent of Greek fire, and so most people do believe the claim to be a real one.

(2) Skylitzes came to the truth nonetheless. Alp Arslan converted because of the kindness of Emperor John. He simply could not believe that such a person could have led his Empire to victory, or indeed last as Emperor in the violent world-not unless he had friends in high places, such as whatever power that defeated the Turks at Manzikert.

(3) Marcionism and other Gnosticism: John II was increasingly being convinced that the Old Testament God could not be the same one as the New Testament one. One preached forgiveness and the other was a genocidal psycho so to say, and he was clear about which one he backed. By the end, he saw the Islamic/Judaic God as a malovolent entity enticing humans astray (the Demiurge-lord of the material world), while the Christian God's fundamental message was salvation-though the Church was corrupted by the Demiurge itself. He was however not loony enough to actually say this openly or act in a manner that would suggest he thought this way. That being said, he also refused to go to the other end and persecute other gnostics like the Paulicans/Bogomils, leading to his eventual downfall (yep, he was poisoned off).

John is not an actual Cathar/Bogomil/Paulican though-just to be clear. He would identify as a Marcionist in the modern era. That being said, his ideas did not develop in a vacuum but owed quite a bit to the intesting neo-Gnostic ideas floating around in Roman society's fringes at that time.

The wikipedia article on Marcionism may be of help if anyone wants to have a quick look at this: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marcionism

Last edited:

Apologies for being off the grid for a bit-had a medical issue, but am prima facie on the road to recovery. Stuff happened here I missed for a bit: I was amazed by the Turtledove total, didn't realize so many people were reading this. I do however note that the last chapter didn't generate normal level of response (one very interesting discussion about France aside) and I am a bit curious about why it might be so. Is it because we are moving away from OTL figures (esp the ever popular Basileos II), is the writing becoming worse, is it too much a wall of text, is it a general decline of interest or am I misreading the situation.

Stay well, folks.

Stay well, folks.

Interesting update, especially regarding Turkish Christianity and Marcionism. One quibble regarding "each theme be ready to supply at least 15000 men for war". Have the themes been reorganized into larger provinces? Because if not, then this is unrealistic. The largest "classical" theme, the Anatolics, had been able to field this number (at least according to Arab geographers) in the 9th century, but certainly not after various provinces had been split off, and the military lands had begun falling into disuse in this role. ITTL, with the depopulation of Asia Minor in favour of other areas, such numbers are impossible, especially since the other themes were much smaller (in particular the numerous Armenian themes and generalships created in the age of reconquest IOTL, which had a permanent garrison of one to two thousand men at most). Overall, thematic armies were useful for defensive warfare, but not for prolonged offensive campaigns, which is why they were neglected IOTL. A more realistic option might be to limit the number provided by the "great" themes to fewer men, but have them serve as a professional, standing army, rather than be called to arms at need. That leaves of course the problem of how to replenish the ranks if a major military disaster happens, but this might be (partly) dealt with by having the thematic troops serve in phases: men in active service for say 15 years, and then in one or two reserve echelons. Or you could have them serve in rotation locally, in a field army, and in reserve. All of this depends, however, on how much of a manpower pool the Empire has to sustain both agriculture and a standing army at the same time.

Interesting update, especially regarding Turkish Christianity and Marcionism. One quibble regarding "each theme be ready to supply at least 15000 men for war". Have the themes been reorganized into larger provinces? Because if not, then this is unrealistic. The largest "classical" theme, the Anatolics, had been able to field this number (at least according to Arab geographers) in the 9th century, but certainly not after various provinces had been split off, and the military lands had begun falling into disuse in this role. ITTL, with the depopulation of Asia Minor in favour of other areas, such numbers are impossible, especially since the other themes were much smaller (in particular the numerous Armenian themes and generalships created in the age of reconquest IOTL, which had a permanent garrison of one to two thousand men at most). Overall, thematic armies were useful for defensive warfare, but not for prolonged offensive campaigns, which is why they were neglected IOTL. A more realistic option might be to limit the number provided by the "great" themes to fewer men, but have them serve as a professional, standing army, rather than be called to arms at need. That leaves of course the problem of how to replenish the ranks if a major military disaster happens, but this might be (partly) dealt with by having the thematic troops serve in phases: men in active service for say 15 years, and then in one or two reserve echelons. Or you could have them serve in rotation locally, in a field army, and in reserve. All of this depends, however, on how much of a manpower pool the Empire has to sustain both agriculture and a standing army at the same time.

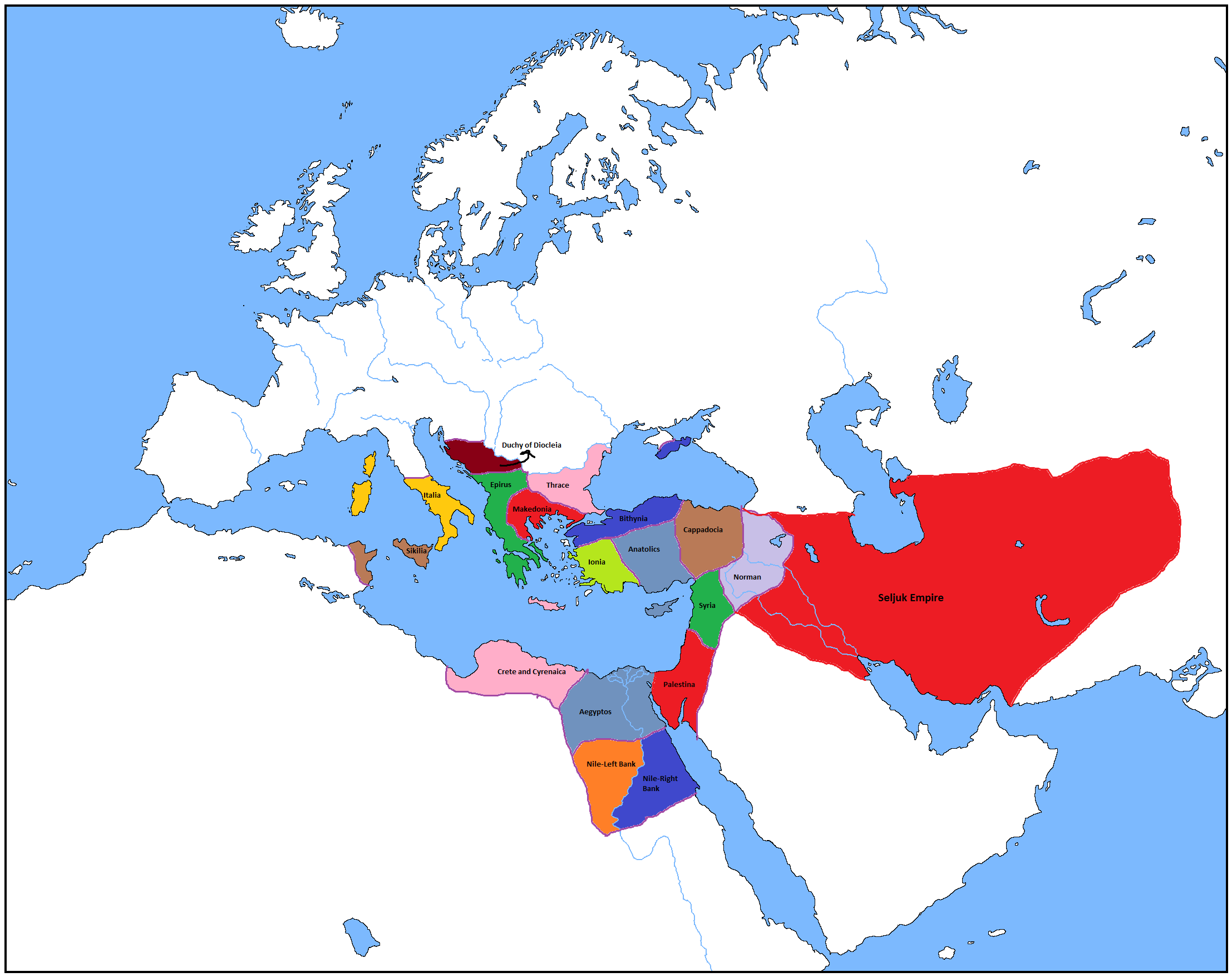

Damn, I thought I had mentioned reduction in number of themes but seems like I missed it (talked only about new acquisitions and not the core). Basil III consolidated themes thinking that they will not be playing defense in Anatolia for a while, and they might as well cut overhead salaries for multiple strategoi (he was secure enough in his position to not quite be afraid of rebellion, until well: things go to shit but he can't turn the clock back). Right now these are the themes (I lost the notes with actual names on it, so going with geography):

1. Bithynia (NW Anatolia)

2. Ionia (SW Anatolia)

3. Anatolics (Central Anatolia and the Med coast)

4. Cappadocia (East Anatolia, Pontus and Armenia, at least the parts not given to Doux Michael)-fusing this one was a huge blunder. The old Armenian frontier bits were carefully joined together over years to create this behemoth, at Alexander Komnenos' behest to be a first line against a potentially rogue Mesopotamia. It worked when he was the effective leader there. After that, not so much.

5. Thrace (North East Balkans, includes Bulgaria)

6. Macedonia (Central Balkans)

7. Epirus (Adriatic and Greece proper)

8. Italy

9. Sicily

10. Syria (North Levant)

11. Palestine (South Levant)

12. Two in Upper Egypt (something very descriptive like left bank and right bank)

13. Crete and Cyrenaica.

The last one has no hope of meeting the number (and everyone knows that). The Anatolians however should be able to meet it: 4 themes covering the whole area should be able to meet the number fairly easily. Egypt could probably muster 20k combining the two themes, but they are also not a super top priority-their only purpose is to provide muscle against Makurian incursions or a Coptic uprising. The Levantine themes will be hard pressed, and the strategoi will be likely getting Arab auxiliaries to meet the total number (but they can hit 25k collectively without that too) . Balkans and Italy/Sicily should also be able to meet the number.

John II ramped this up as he wants to play defense. He has hiked tagma levels as well, but it is mostly for a show (Basil II did not need to keep a 50k army in Egypt at all times) and in reality professional boots in Anatolia are fewer on the ground even with these changes. Giorgios I on the other hand is almost certainly going to go on the offense and increase tagma commensurately with the size of the Empire unless circumstances make trouble.

The rotation strategy is a good one, but the next few leaders will not implement it because of their own beliefs-to the detriment of the Empire. It will be done much later, once they realize the spend/cut cycle strategy is unsustainable. It also helps that they are not at all recruiting from the Nile delta yet , which allows them to use the Egyptian surplus to feed the 50k men they have stationed there and some more back in Anatolia.

Here is a full map of all the themes/provinces. Some look weird (why on earth would Crimea be ruled from Bithynia) but those external territories (Carthage, Sardinia, Corsica, Cyprus etc) have their own junior commander and effectively independent administration. It is just that their defense is also the responsibility of the main theme (so the strategos there is the nominal boss and must send soldiers if there is an attack. In practice it means the core theme must send some soldiers on rotation there at all times since reacting to an attack will take too long). Diocleia is a non-hereditary Duchy hanging out in the Balkans since Epirus is too big, but it can be reorganized.

The Normans constitute the Duchy of Mesopotamia. They have been overeager to bite chunks out of (formerly) Turkish Armenia when Mesopotamia further south became a tougher nut to crack. They dont want to invade the Empire though, Constantinople has some good hostages like the Doux's eldest son and it is far better to let the golden goose give them cash to hire more men and expand borders. The Seljuk Empire however is still breathing and fighting back. They have lost some lands in the East to fellow nomads, but those are nothing compared to Persia proper and Mesopotamia.

The Normans constitute the Duchy of Mesopotamia. They have been overeager to bite chunks out of (formerly) Turkish Armenia when Mesopotamia further south became a tougher nut to crack. They dont want to invade the Empire though, Constantinople has some good hostages like the Doux's eldest son and it is far better to let the golden goose give them cash to hire more men and expand borders. The Seljuk Empire however is still breathing and fighting back. They have lost some lands in the East to fellow nomads, but those are nothing compared to Persia proper and Mesopotamia.

Also, now that the suspense is over-here are the big things that will matter, not the humble Emperor Ioannes II.

1. Norman Mesopotamia-The temptation to use Normans on a frontier territory of the Empire was too strong to resist. No prizes for guessing that relationship will be going hot relatively soon and a major clusterfuck will happen. The one problem for the Normans is that they are too far from Rome and too close to Constantinople, and they need to keep the Emperor happy to ensure the sea lane to Syria and the land route from there to Mesopotamia is open. Without that, they are well and truly fucked. They are also building a rather feudal state there, giving large land grants (who gives a fuck about Assyrian/Armenian serfs? At least Kaisar Michael removed kebab), and really need more expansion to the fertile south to keep the Ponzi scheme running. Still, they'd rather have more support than less, and are thus calling for help from the "West".

2. The First Crusade: Circumstances are different, but Western Europe is ready for war. They spent a century hearing about the massive reconquest in the East and the capture of Jerusalem. They also heard from successive pro-Empire Popes how it was German interference that led to the loss of Jerusalem to Dawd but the great Emperor Basil got it back. They can't blame the Greeks too much since the latter seem to be getting results and there is some feeling of inadequacy. Travellers are also peddling fantastical stories (based on some reality) about the wonderful Eastern Empire where everyone has land and no one goes to bed hungry. Manzikert came as a shock for them, but they thought the East could pull through. It seemed that way until Mr Leo the former Sultan came calling to the Pope asking for help. The Pope Alexander sees his chance in John II's reluctance. Catholicism has not been able to expand in the muslim world as Constantinople got their way. He also has a grand delusion about being the Alexander to finally "conquer" Persia (spiritually), and in Leo he sees a chance to do it. He calculates that John II will not be able to actually stop him because of factional fights in Constantinople (as Apocarius/Papal Legate to the City, he knows a lot more about this). So he peddles a compelling narrative: A Great King dispossessed of his realm because he accepted Christ, and the East too weak to help because of some past mistakes. Who will take up the mantle for Christendom then but the West? Has their moment not come? W.Europe also finally has enough population to wage this sort of war, and a generation of nobles raised on fairy tales finally see their chance to gain glory in the fantastic East in the name of Christ.

John does however hit back by reminding them of Spain (his masterstroke) which does suddenly remind a lot of people that yeah, there is a closer target. Yet, the whole horde does not go on the full reconquista since they firstly don't have an obvious candidate like Leo Arslan or a good story, plus they know the money is not there compared to Mesopotamia, but it does reduce Crusading vigor to the East considerably compared to OTL. This is where Venice and Genoa step in-they are tired of the Egyptian monopoly on Eastern trade with the land routes fucked up, and they think bases in the Persian Gulf and Mesopotamia would let them bypass Egypt. So they stir up the fervor for their benefit, and thus have a respectable movement going. Still boatloads weaker than OTL first Crusade, but it is something.

3. But what will the Muslims within the Empire do? They have forgotten what Shaitan was capable of, and were reassured by the Synod of Constantinople. This regime change however is sending alarm bells ringing in their minds about what their role is in the Empire.

Ideas and suggestions welcome- I do have plans but discussions here help me hone things much better

1. Norman Mesopotamia-The temptation to use Normans on a frontier territory of the Empire was too strong to resist. No prizes for guessing that relationship will be going hot relatively soon and a major clusterfuck will happen. The one problem for the Normans is that they are too far from Rome and too close to Constantinople, and they need to keep the Emperor happy to ensure the sea lane to Syria and the land route from there to Mesopotamia is open. Without that, they are well and truly fucked. They are also building a rather feudal state there, giving large land grants (who gives a fuck about Assyrian/Armenian serfs? At least Kaisar Michael removed kebab), and really need more expansion to the fertile south to keep the Ponzi scheme running. Still, they'd rather have more support than less, and are thus calling for help from the "West".

2. The First Crusade: Circumstances are different, but Western Europe is ready for war. They spent a century hearing about the massive reconquest in the East and the capture of Jerusalem. They also heard from successive pro-Empire Popes how it was German interference that led to the loss of Jerusalem to Dawd but the great Emperor Basil got it back. They can't blame the Greeks too much since the latter seem to be getting results and there is some feeling of inadequacy. Travellers are also peddling fantastical stories (based on some reality) about the wonderful Eastern Empire where everyone has land and no one goes to bed hungry. Manzikert came as a shock for them, but they thought the East could pull through. It seemed that way until Mr Leo the former Sultan came calling to the Pope asking for help. The Pope Alexander sees his chance in John II's reluctance. Catholicism has not been able to expand in the muslim world as Constantinople got their way. He also has a grand delusion about being the Alexander to finally "conquer" Persia (spiritually), and in Leo he sees a chance to do it. He calculates that John II will not be able to actually stop him because of factional fights in Constantinople (as Apocarius/Papal Legate to the City, he knows a lot more about this). So he peddles a compelling narrative: A Great King dispossessed of his realm because he accepted Christ, and the East too weak to help because of some past mistakes. Who will take up the mantle for Christendom then but the West? Has their moment not come? W.Europe also finally has enough population to wage this sort of war, and a generation of nobles raised on fairy tales finally see their chance to gain glory in the fantastic East in the name of Christ.

John does however hit back by reminding them of Spain (his masterstroke) which does suddenly remind a lot of people that yeah, there is a closer target. Yet, the whole horde does not go on the full reconquista since they firstly don't have an obvious candidate like Leo Arslan or a good story, plus they know the money is not there compared to Mesopotamia, but it does reduce Crusading vigor to the East considerably compared to OTL. This is where Venice and Genoa step in-they are tired of the Egyptian monopoly on Eastern trade with the land routes fucked up, and they think bases in the Persian Gulf and Mesopotamia would let them bypass Egypt. So they stir up the fervor for their benefit, and thus have a respectable movement going. Still boatloads weaker than OTL first Crusade, but it is something.

3. But what will the Muslims within the Empire do? They have forgotten what Shaitan was capable of, and were reassured by the Synod of Constantinople. This regime change however is sending alarm bells ringing in their minds about what their role is in the Empire.

Ideas and suggestions welcome- I do have plans but discussions here help me hone things much better

How friendly is the new Emperor with the Latins? Seeing as the Roman military isn't in a decrepit state relative to OTL would he be open to simply throwing Latins at the Turks until he can move in with a proper army to clean up?

How friendly is the new Emperor with the Latins? Seeing as the Roman military isn't in a decrepit state relative to OTL would he be open to simply throwing Latins at the Turks until he can move in with a proper army to clean up?

Giorgios I wants to hire you as an advisor. Please send your CV to Blachernae within the next 24 hours.

This is exactly his plan-let Latins be cannon fodder and weaken the Turks before he rides to their rescue. Unfortunately (as OTL first crusade post Antioch showed, Alexios not turning up made no difference to what the Latins could do)-the best laid plans of mice and men can go terribly wrong and he may have just worsened the situation.

Also damn, I was re-reading the update and realized I totally forgot the notes...... Crap, sorry-I inserted them, and here is the copy paste so that you need not re-read it all.

Notes:

[1] Apocarius: Papal legate to Constantinople. The Alexander in question later became Pope (as noted in the chapter) and wrote History of the Roman Empire - the standard text concerning the Latin Empire (Principate and Dominate) which runs from Augustus to Phocas. This work of scholarship took much effort, and extensive perusal of documents in Constantinople and is the only material that preserves contents of major Latin writers whose works were burned by John Callinicus.

[2] Alp Arslan becoming Leo: Alp Arslan means "Heroic Lion" in Turkish. Leo was thus the obvious choice for a baptismal name.

[3] Nestorian Seljuk: Seljuk had only converted to Islam in 985, and he had sons called Michael and Israel, suggesting a Nestorian past (not really, but that is the TTL belief).

Vasilas' Notes: