'They are more to me than life, these voices, they are more than motherliness and more than fear; they are the strongest, most comforting thing there is anywhere: they are the voices of my comrades'

~ Erich Maria Remarque,

All Quiet on the Western Front

‘On the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month the First World War finally came to an end. After four years the guns went silent but even as the victors mulled over the peace they would largely dictate to the defeated Germany, the survivors of the conflict would not rest. Germany’s future remained in the balance and those who had signed the armistice handed to them in Marshal Foch’s private railway carriage realised that power was very quickly slipping away from themselves as well. They had signed on behalf of a Kaiser who had already abdicated, a man who had ingloriously fled to the Netherlands to allow the new provisional republic to sort out the chaos he had left in his wake. The situation would remain unstable long past the Kaiser’s death from Spanish Flu.

The revolution emanating from Kiel had spread with astonishing speed, though the way in which it presented itself varied widely. In some areas workers councils were formed as little more than advisory boards to the general management, others demanded more radical and arguably unfeasible changes to their hours and wages. Artists formed their own collectives and attempted to become the vanguard of a new cultural beginning for Germany. Others settled scores, unpopular managers were thrown into rubbish piles, punched, and in one case thrown down a mineshaft.

Despite being characterised as a conservative region, Bavaria was not immune to this revolutionary wave and though initially bloodless, events there would soon give the young Hitler his first taste of a genuine revolutionary conflict. ’

~ Geoffrey Corbett,

Hitler’s First Revolution

The barracks were draughty though the troops inside had patched them up the best they could. The war was over, yet unaccountably they remained in the army and remained garrisoned. Some pondered their fate, most just seemed relieved to have survived the war and to be back in Germany.

The soldiers largely busied themselves in small groups, swapping pieces of bread for cigarettes, cracking dirty jokes, telling each other presumably exaggerated tales of heroism and survival. Every now and then there was even a ghost story in the dark afternoon. Adolf sat amongst those he had come back with, calculating in silence.

An opportunity had arisen, one that couldn’t be dismissed out of hand.

He hadn’t seen Friedrich since their near escape from the collapsing Hindenburg Line. The two had been separated shortly after they’d reached safety by a highly strung lieutenant who accused them both of cowardice, seemingly ignoring the badly injured man they’d brought with them. Probst had died shortly after, though Adolf had sat in wait on the sliver of French territory the German Empire still held until ordered to evacuate. Allegedly Friedrich had broken his interrogators nose and had been sent behind the line. He would have been immediately shot for that previously, though developments had made it clear that the army was now terrified of its own shadow.

It was a fear that was vindicated, and on the march back home Adolf had become aware of what had unfolded on those last days of the war. The sailors at Kiel had refused to be used as cannon fodder like he had been and had been organised enough to throw out the old regime entirely. All around Germany people had begun to follow their example, the war had been a devastating experience and it seemed that most now agreed with Adolf that those who had caused so many Germans to die for nothing would never be allowed to make the same mistake again. What he had often wondered about on the front was now appearing in front of his eyes, the soldiers were taking things over for themselves and the German people were following their lead.

He wasn’t sure what this phenomenon was exactly, he had heard lots of talk of communism recently though there seemed something far more organic about this German revolution and Lenin’s actions and decrees. He’d read that Marx had predicted it should be this way, a natural conclusion of the old system, and the theorist had been German after all. The people had outgrown the old system of conquest and elitism, it was too bad said system had had to take so many millions with it as it destroyed itself.

He was glad to be alive but he knew that surviving also carried new responsibilities. What exactly those were he wasn’t quite sure about but in this new world where everything seemed to be fluctuating who knew which opportunities might knock on door?

The figure who actually entered the barracks looked much like the rest of the soldiers, khaki-clad, weary, half-starved and half-dead. All that distinguished him from the rest was the red armband tied around his shirt and a fire in his eyes to match.

“Comrades,” he bellowed despite the fact he didn’t look as if he had such volume in him, “I’ve come with a proposal that needs to be decided upon. Its details can be discussed in time but a provisional decision needs to be made immediately.”

A look of confusion went through the shed as the “Comrade” took what appeared to be an unfolded cigarette packet out of his jacket and began to read from it.

“We, the soldiers of Bavaria, formally reject both the new authority of the Bavarian state and the Berlin provisional republic. He hereby declare allegiance to the Bavarian Soviet Republic and swear to defend it for the duration of the coming struggle.” The lofty didactics did not particularly resonate but most already knew what was going on. The communists had already taken over Munich by the time Adolf arrived. They had largely left the soldiers to themselves, but he supposed it could only have been a matter of time before they sent out feelers to see if they had mutual aims, though it was immediately clear that not everyone did.

“I ought to drag you out into the courtyard and kick the shit out of you, you treacherous wretch! It wasn’t bad enough that your sort lost us the war but now you want us to help dismantle what’s left of Germany?! Go to hell!”

Adolf didn’t know the man, but he knew such an argument had to be countered, nonetheless few spoke up against him. He realised that the opportunity may have come quicker than expected as he felt himself shouting amongst the murmurs

“Whose Germany do you think they’re dismantling? It certainly wouldn’t be ours!” The huddled solders turned to face Adolf, as did the man at the door. The men had had travelled with still sat, surprised the man who kept to himself had shouted, looking at him as he was a paralysed man who had just realised he could walk. There was no such confusion from the heckler.

“I fought for Germany for four years, I held off the froggies all that time, even if it meant not eating for days, even if meant using

my dead comrade’s bodies as

cover and you think that it was all for nothing? You honestly believe that millions of our fellow Germans

died for nothing?!” There was snarl in his speech, his face contorted with rage, this was a man who had fought, there was no doubt about that but he was still wrong and despite the initial embarrassment of shouting down the barracks Adolf realised that there was no going back now.

“I also fought for Germany for four years on the front, I realise that you and I both have likely seen things that no man should ever, endured suffering that no-one should ever have to endure but why was that so? Those in charge, they’re the ones who put us through that hell! Those who believed us to be no better than the vermin that they made us live amongst in the trenches! The aristocracy, the fat cats, the high command, everyone who sent us to fight whilst they sat far behind the line in comfort! Those who sent us to fight for a lie! I don’t believe I fought for nothing, oh no, the clarity that I found on that front will never leave me and that rage has spread itself amongst the German people. Now it is time to act before they put us back in the cage!”

There were murmurs of approval, someone shouted their agreement, it seemed to show that the rage was infectious, at least amongst these defeat outcasts. Some were immune of course, and the heckler was certainly not placated.

“We were screwed all right, there’s no denying that. Idiots at the front and weaklings back home got us into this mess. Germany must be rebuilt but it must rise again in strength, I’m not going to be a party to this con, the communists will lead us to ruin and then the foreign powers will eat us alive!” There was agreement to this as well, albeit not by many of those who had seen eye to eye with Adolf. The man had gone silent now but he still stood, looking suspiciously, as Adolf composed himself. The hut was quiet now and he spoke slowly and quietly.

“I agree. Germany needs to be strong, we must face down our enemies even in temporary defeat but that can’t be accomplished by maintaining the current order of things. The Kaiser may be gone but his cronies remain, if they continue to lead this country then we will be no better than when they led us before and all the while they will continue to treat us as vermin. Kurt Eisner tried to talk to them, tried to work with them for a better Germany and their agents show him down! There can be no parley with these people, they will only see it as submission. It is time to set them straight!”

This time there was actual applause, the rant was incoherent but it had captured a mood. The anger was widespread and soon the entire hut that broken out into individual arguments, the heckler wading past several others to scream in Adolf’s face. The two hadn’t quite finished comparing who was braver and more patriotic based on their war experiences before the booming voice from the man at the door echoed around the room once again in an attempt to restore order.

“Fellow comrades…comrades!

Gentlemen! Please!” There was silence at last, the heckler had been so close to Adolf that he could smell his greasy blonde hair but now even he turned round to listen.

“This idle bickering will get us nowhere, we need to act fast. We need to know your stance on the proposal.”

“Here’s a proposal, find a bridge and jump off it!” Adolf winced as the heckler screamed right past his ear, he got a few laughs.

“That won’t help anything!” Adolf was trying to address the crowd though he purposefully screamed right in the heckler’s face, the man wrinkled his brow and covered his nose.

Is my breath that bad? Adolf pushed the thought away, it seemed as if he were some sort of spokesperson now.

“Let’s put it to a vote! Do we want to throw the

comrade off a bridge or do we want the bastard’s who got us into this mess to throw us all off one?”

Without missing a beat, the man at the door responded with a request for hands in favour of the proposal. Adolf immediately raised his right arm, though at a slant to make sure he didn’t accidentally bat the heckler in the face and cause a brawl. It appeared that the majority of the hut had raised their hands in favour as well.

“That’s settled then!” The man at the door’s voice boomed again and he seemed even more confident than before. Adolf could feel him smiling at him, if just for a moment. “You’ll need to form a soldier’s council, you won’t take your orders from anyone but yourselves but the revolution will need discipline nonetheless. Would anyone like to put themselves forward as a provisional convener?”

“I nominate this bastard!” Adolf merely fell forwards to the ground as the heckler slapped him on the back. “He’ll see how smart he is when he doesn’t need to sit at the back and make speeches.” The snarl was still in the man’s voice but as he looked round Adolf could see that he was smiling at him now as well.

---

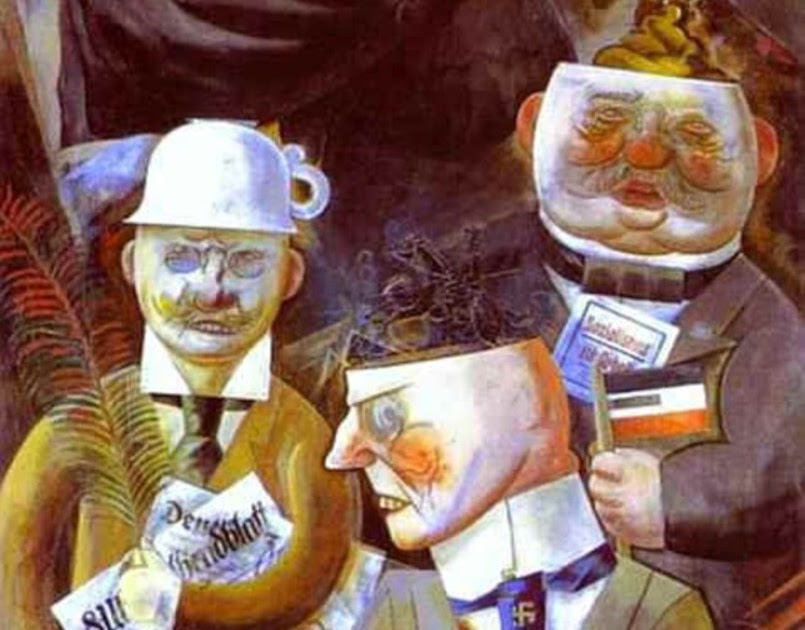

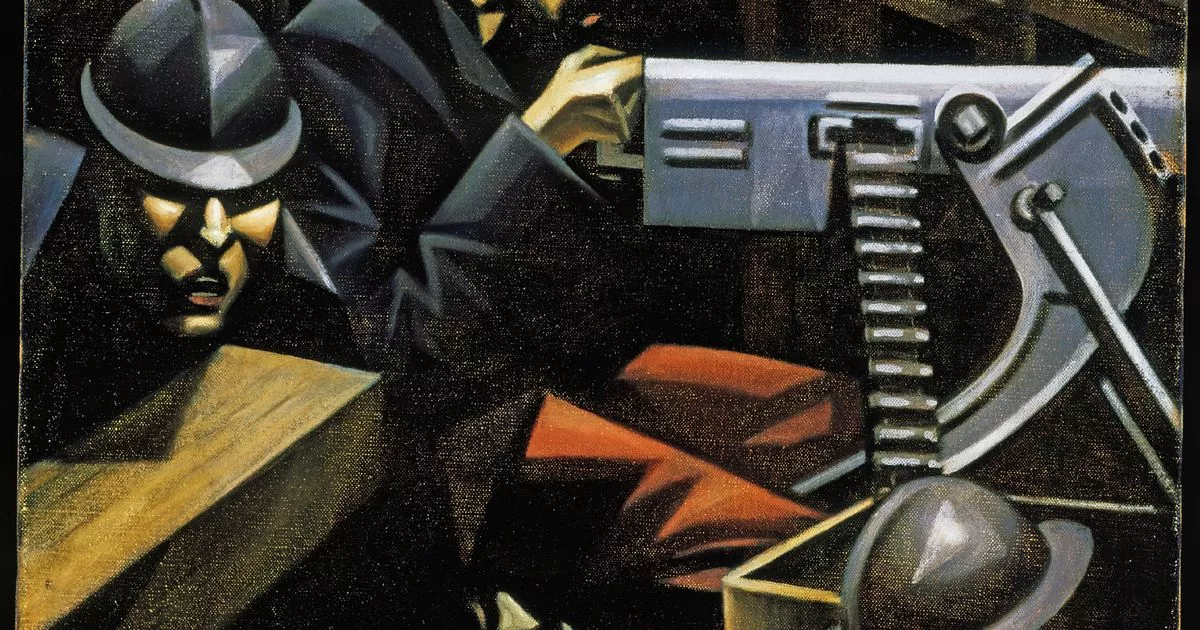

The painting is

Picking Up The Banner by Gely Korzhev