You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

"Our Struggle": What If Hitler Had Been a Communist?

- Thread starter The Red

- Start date

Is that Hitler? In Our Struggle-verse he has OTL hair but no mustache.Hmmm

Is that Hitler? In Our Struggle-verse he has OTL hair but no mustache.

Chapter CXV

We have always predicted that capitalism, having reached its decline, would not fall on its own sword like a ripened fruit. We have never ceased repeating that it would defend its privileges by every violent method, not retreating before fascism and terror.

~ Marcel Cachin, In the Factories, at the Building Sites, and at the Stations:

Demonstrate!

~ Marcel Cachin, In the Factories, at the Building Sites, and at the Stations:

Demonstrate!

Although the circumstances in which the French people found themselves following the end of the First World War made the demise of democracy a likely outcome it would be wrong to consider that the rise of the Pétainregime in France was somehow preordained. The takeover of France by reactionary forces was drawn from lingering resentments found at the beginning of the Third Republic but also the contemporary global crisis.

The Great Depression was a global crisis but it had arrived in Europe via Germany. German dependence on American investments and loans had seen the country dragged into economic freefall with the Wall Street Crash almost as quickly as the Americans themselves. The French, like the Americans, had maintained an adherence to Gold Standard but in their case it had allowed them to weather the storm. This was because they had manipulated their currency to stabilise their economy, leaving the Franc undervalued in a deflationary shock. Although this had caused problems for the French worker prior to the crash in terms of higher prices and lower wages than their American or German counterparts it had left the French economy far more robust than any other capitalist power. France became seen as a safe haven for capital and the lifting of exchange controls had made it so that by 1932 a third of the global gold supply was held by France.

This financial stability allowed the French government to pursue state spending to prop up industry in a time where austerity measures were being implemented in all capitalist economies. This strategy did not prevent an increase in unemployment and an economic downturn within France following the German Civil War but the French economy remained the healthiest in Europe for a time. The recovery of first the German and then the American economies would unsettle this and as her economic rivals remerged, French protectionism began to grind the economy to a halt. The depression would only truly catch up to France in the midst of other powers beginning to recover.

Unemployment skyrocketed in a way the successive had previously assured the French people they were insulated from, the spending used to keep industries afloat had now vanished and in its place were severe cuts to social programs. Disillusionment with the republic was nothing new with French public life and though the French people were now suffering in a way that was common throughout Europe, the drastic solutions being proposed had already had the groundwork laid for them by the preceding decades of turmoil. Whilst the political tensions were heightened by the depression spread across Europe, in France they had already been simmering for a long while.

The French Third Republic was not beloved by its people. It was a regime borne of a bourgeois revolution and a stifled proletarian one, both having played out with the end of the Franco-Prussian War. Its main legislative organ was an assembly that by the interwar years was evenly divided between centrist, conservative, liberal and socialist parties. This led to countless governments being formed over the twenties and early thirties, none lasting particularly long.

The character of these coalitions was somewhat consistent, tending to be made up of centrist and conservative figures. and although the rise and fall of successive governments, some only lasting a few days, set-up an almost permanent instability within the French legislature. France was still able to function for as long as the economy remained healthy enough to avoid popular discontent but with economic turmoil came threats from familiar opponents to the bourgeois democracy the republic was built upon.

This legislative strife had already led to increased militancy on the left but it was divided by the time the crisis point came. The two primary left-wing parties at this time were the social democratic French Section of the Workers International (SFIO) and the Comintern-aligned French Communist Party (PCF) with both being at odds with one another.

The SFIO had been the primary party of the trade unions and the working class since the beginning of the twentieth century with its own Marxist origins. These had been put aside in the face of the First World War in a similar way to their German counterparts in the name of a more patriotic approach that saw them abandoning the class struggle to collaborate with French parties across the political spectrum in the name of victory.

The war had dragged on with the SFIO becoming increasingly disenfranchised. The bloodshed and destruction left the party shaken whilst different coalitions throughout saw them increasingly lose influence. Even in victory there was widespread disgust at what the war had wrought on the French nation. Many were left jaded with the patriotic effort and looked towards the ongoing revolution in Russia as an example for the French proletariat to follow. Indeed this was the view amongst the vast majority of party members, when it came to a decision on whether or not to join Lenin’s new Communist International almost two thirds voted to do so. The party leadership disagreed and amidst violent clashes the French Communist Party came into being, taking much of the party membership with it alongside the SFIO paper, L'Humanité.

The enmity that arose from this split had only grown in the prevailing years of economic and political instability throughout France. Whilst it had initially seemed the PCF might go the way of many left-wing splinters it would become a political force throughout the twenties, gaining seats in the legislative assembly and presence within the trade unions, particularly the railways and the burgeoning aircraft industry. This success came largely at the expense of the SFIO, leaving the working class divided in France.

The PCF grew stronger but also underwent the process of the ‘Stalinisation’ far more seamlessly than their German counterparts, indeed they joined in the condemnation of Hitler and the KPD after the German split with the Comintern in 1930. A reappraisal of Hitler followed in the wake of the United Front’s victory in the German civil war and their subsequent rise to power but the KPD were still seen as having missed rather than gained an opportunity for the total overthrow of capitalism by the PCF leadership. Any such cooperation with the SFIO was dismissed and the feeling was mutual with factions within both parties being purged for advocating for a similar approach.

These elements would unite with other disparate leftist groups to form what would in time become a major force within the ‘Renaissance de l'espoir’ movement, the Popular Workers Party (PPT.) For the moment their relevance was minor, their influence being relegated to a handful of towns and a few suburbs with Paris. They would one day come to supplant the reactionary forces within France but at this moment it was the forces of reaction which in the ascendancy. With the left divided it was they who posed the true threat to the Third Republic.

Although the state of the French left was not dissimilar to that of Germany prior to 1930 the same could not be said for the forces of the right. The Third Republic had always been plagued by reactionaries who saw its inception as the defining moment of French decline. The nature of this varied widely and often hung on resentments based around major crises within the life of the republic, whether it was the Paris Commune, the republican secularisation campaigns against the Catholic church, or most infamously the Dreyfus Affair.

The Dreyfus Affair had been a scandal in which the French artillery officer Alfred Dreyfus had been convicted of spying for Germany. The evidence for Dreyfus’ conviction was weak however and the eventual reexamining of the case heightened divisions in France. Dreyfus’ Jewish background and the prejudice he had faced because of it won him sympathy in many liberal and left-wing circles, however it also gave rise to new antisemitic and reactionary forces across the society and increasingly within the French military. Dreyfus himself was eventually reconvicted but released upon his acceptance of his initial guilt, a messy compromise designed to settle the affair. Instead the divisions from the incident would only produce a lingering resentment.

The two primary movements within the French far-right were French Action (AF) who had arisen in reaction to the Dreyfus Affair. Predating the development of Italian fascism this group were embodied with the same beliefs that Mussolini would later impose on Italy; ultranationalism, militarism, and a fervent Catholicism which endured regardless of the Catholic Church officially proscribing the organisation. They were also monarchists, and though Mussolini would also support the monarchy in Italy, the AF saw a return of the monarchy as an instrument of national revival.

In these goals they were joined by the Patriot Youth (JP), a paramilitary league which framed itself as the continuation of the patriotic desire for revenge against Germany prior to the First World War and now saw themselves as patriotic defenders of the French people from any perceived threats. What they believed these to be were similar to the enemies of the AF and were willing to work alongside them in the joint aim of bringing down the republic’s parliamentary democracy. Both could rely on a broad range of support from sources which were not actively reactionary in their politics but willing to tolerate such movements both at home and abroad,

The strongest in number were the Cross of Fire (CF), another veterans league albeit one which at this point in time claimed to be non-political. All the same their tens of thousands of members were ready to join in something which could be framed as an anti-communist cause. Many French business leaders and industrialists maintained a similar perspective. In this they were joined by American and formerly German investors who missed the days of France being a financial safe haven. The Catholic church, who had been wary of the Third Republic’s existence ever since its inception, were willing to turn a blind eye. The Holy See had been actively at odds with France ever since the republican’s secularisation campaigns in the late nineteenth century.

However, not even the Pope could have called upon the same level of support as Philippe Pétain.

Marechal Pétain’s victory at Verdun in the First World War had made him a living legend and had granted him levels of popularity that few would-be dictators could dream of. In Petain the reactionary right had the leading figure that neither Hohenzollern nor von Schleicher were able to be. Though well into his seventies by 1934 he was happy to entertain notions that he would be the man to lead the nation towards the national rebirth his adherents on the right were calling for. In this the military were willing to follow him.

The Bastille Day celebrations of 1933 featured a parade of the French military through Paris as its highlight. The quintessentially republican holiday commemorated the storming of the Bastille fortress which signified the beginning of the French revolution. The military were sworn to protect the republic but they had long since grown wary of their democratic masters. The Dreyfus affair had alienated them from the French left and bred scepticism of the democracy they were supposed to uphold. Many officers of monarchist or religious backgrounds had found a home amongst the reactionary right. Many others were simply frustrated over the seeming inability of republican governments to deal with German rearmament whilst suppressing their own desires to professionalise the army. This fueled a feeling throughout much of the officer corps that the republic had to be dismantled for the good of France.

The reactionaries had the strength and cohesion needed in order to carry out their own vision for France but in Pétain they had the final, decisive, piece of the puzzle. Now all that was needed was a spark, one which a divided and disillusioned left could only react to when it came.

A fresh scandal would be the perfect opportunity.

~ John Penny, The Unpopular Front

---

---

Sacré-Cœur, Paris, February 1934

The Sacred Heart basilica stood awkwardly over the capital, above it and beyond it. It had been built in opposition to a century of moral decline that had culminated in the dawning of the French Third Republic. It had stood in judgement of the French people ever since, a visual display of what the liberalism, socialism and secularism of the Third Republic had allowed to fester. It had stood over them in glory, offering an alternative. A path to renewed French strength through the one true faith.

The Third Republic was at last drawing to a close and Colonel Charles de Gaulle could think of no better site to announce it from. Marechal Pétain, the man all of France now looked to, had decided to call time upon it from this sacred site of all that was pure and holy in France.

He spoke now to an assembled crowd of tens of thousands.

A stage of sorts had been constructed in the hours beforehand, with a speaker system hooked up to allow the Marechal to project over the vast crowd gathered around the basilica. De Gaulle stood upon it with several other young officers, flanking the Marechal whilst doing their best to embody the military discipline France needed.

The Marechal had begun by addressing the French nation on the ill winds he had seen brewing at home and abroad. He spoke of how the time had come to dispense with the years of failure and intrigue that had darkened the post-war age. The time had come to act.

It had started with a scandal.

The affair was tempestuous by any measure. The defrauding of Parisian pawn shops via worthless financial bonds had been rather unique in defrauding both the richest and poorest in Parisian society.

The culprit behind the fraud, Serge Alexandrovich Stavisky had pulled off large cons before but had eventually found himself out of his depth with his one. To defraud the city he had involved many in the highest reaches of Parisian society in his schemes. Including former liberal cabinet ministers.

For the right this was made all the worse by Stavisky’s religious background and his foreign origins. When justice had caught up with him the previous month he had taken his own life but the scandal had burned through society regardless. Action Francaise had made great play of the scandal, framing it as both a Judeo-Bolshevik plot and a masonic conspiracy designed to undermine what little decency the French people had left.

De Gaulle did not care for Jews personally but even he had felt uncomfortable with some of the gnashing of teeth around the affair. The wave of unrest that had followed, the tens of thousands of indignant rioters in the centre of Paris had called for military intervention.

This was not extraordinary in French history, but rarely had the army been on the side of the rioters.

Quelling the riots had summoned the army to Paris, Marechal Petain had different plans however.

The Marechal had spoken briefly on the affair itself but he had quickly alluded back to the rot it was indicative of before declaring the path ahead. It was one he had already relayed to his subordinates at the war college when he had first made his plans clear.

De Gaulle had obeyed him and his presence had brought order to the mob in an unnatural fashion. The entry of the army into the city with Petain at its head had brought acclaim from those seeking a more definitive end to the republic via the scandal whereas those on the left of French politics had reacted with their own protests. It had been easy to put these down, ironically with the aid of those who had previously been the source of disruption.

The news that the government had fled the city in reaction to Petain’s entry into the city had received a mixed reaction from within the ranks of the war college. Those who had been eager to see the military take its proper place within French society as the defender of the nation from Communist subversion and previously unchecked German aggression had to contend with those wary of igniting a civil war. Most however, had been willing to follow the Marechal regardless of their personal doubts.

The conscripts had mostly done as they were told and the majority who hadn’t had chosen to desert. There were few signs of armed scuffles as of yet, though from his standpoint de Gaulle could see smoke plumes emanating from the banlieues. It appeared the revolutionaries had been less prepared for this turn of events than their German counterparts, there had been no signs of an armed uprising from them either. Indeed the only immediate danger came from Germany directly where de Gaulle feared desertions might leave France temporarily exposed, even in the name of strengthening her against the German threat.

Still for every deserter there had been a veteran willing to replace them, the popularity of Pétain was not merely down to Verdun after all. For many veterans of the world war Pétain had been their only true voice in a position of power and now many loyally came to his side. De Gaulle was certain that any attempted revolution, any German invasion, would be crushed. Not necessarily by guns but by the bonds that had been built in the trenches. The sort of fraternity he had sought ever since he was a young boy.

Pétain now spoke with this spirit and de Gaulle felt all his doubts drain away.

“It is no longer a question today of public opinion, often uneasy and badly informed,” he now stated,

“For you, the French people, it is simply a question of following me without mental reservation along the path of honor and national interest. If through our close discipline and our public spirit we can conduct ourselves in the same fashion as so many did at Verdun then France will surmount her enemies and preserve in the world her rank as a European and colonial power.”

This pronouncement brought more cheers from the crowd but even to those behind Petain it had suddenly become clear that his face had turned stern.

“Authority no longer emanates from below. The only authority is that which I entrust or delegate.”

If the crowd was shaken by that pronouncement, the Marechal did not give them a chance to consider it. That was now his right, after all.

After the promise of a return to order and glory once again Petain’s speech came to an end. He moved from the microphone as the audience was still displaying their acclaim, even whilst the fires on the outskirts of the capital worsened.

The Marechal stopped in front of de Gaulle before the assembled officers departed the rickety stage.

“If it is to be my last act on this earth I will see my country’s future secure. I know you believe these political aspirations to be my indulgences but they are hope of France and they are vibrant. And so, my friend, are you. We need a professional military and we need your theories underlying it. The Germans will already be trying to capitalise on this moment of temporary weakness. Together, we will ensure they are put down once and for all.”

For once, Charles de Gaulle felt lost for words but at last they came.

“Together, my Chief.”

---

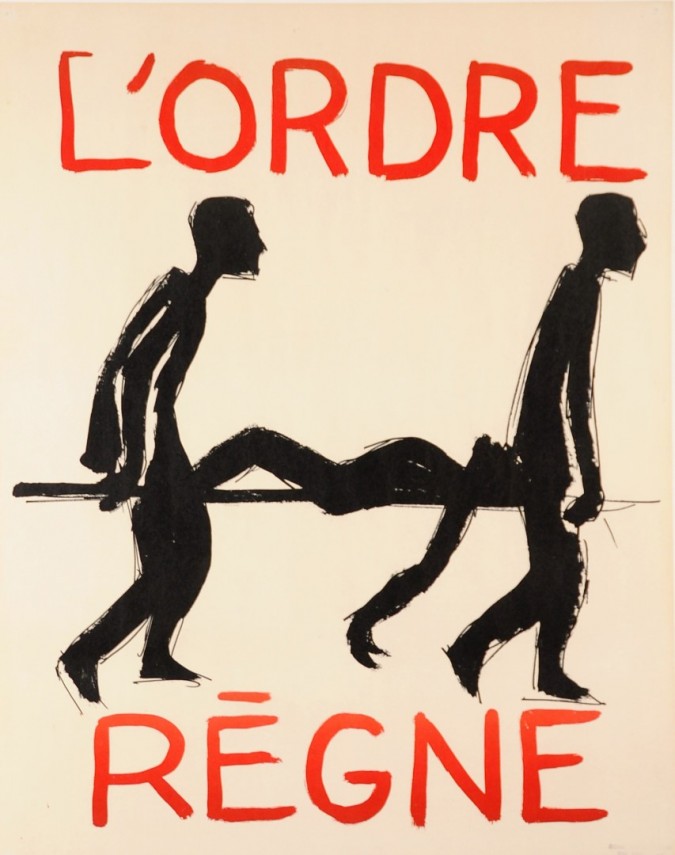

Order Reigns was one of many posters designed and produced anonymously by Atelier Populaire during Mai 68

Last edited:

Thus the pieces begin falling into place, and with it, so goes French democracy.

I'm curious to see what kind of role the other French far-right parties play in Petain's new government. Considering his line about authority, I doubt he would trust giving power to people outside his personal clique, but who knows.

Stifled?The French Third Republic was not beloved by its people. It was a regime borne of a bourgeois revolution and a stilted proletarian one

No doubt.When justice had caught up with him the previous month he had taken his own life

Just looked it up in Youtube and watched what appears to be a contemporary newsreel version.The embedded video is unavailable -- was it Marechal, nous voila?

Holy sh!t! The Gallic führerprinzip !

Thus the pieces begin falling into place, and with it, so goes French democracy.

The Third Republic is the most interesting period of French history (and one of the most interesting periods of history in general) IMO. It remains the longest lived of any French republic and despite rarely being stable and being exposed to numerous threats throughout its lifespan it required foreign invasion to finally dismantle it. Even then it ultimately dissolved itself. The potential of Petain launching a coup was only one of those threats IOTL but here it's come to pass and he now has much of a free reign to carry out his Révolution nationale.

I'm curious to see what kind of role the other French far-right parties play in Petain's new government. Considering his line about authority, I doubt he would trust giving power to people outside his personal clique, but who knows.

Ultimate authority resides with him but the regime won't rely on rule by decree in the same way Vichy did. There will be a constitutional convention to decide upon the nature of the new regime and in that the far-right parties will have a lot of influence. There will be some ministerial appointments as well.

Is "my chief" like the french version of mein führer?

Like Führer translates to leader and the french word for leader can be tranlated back into english as chief?

Kinda, Chef essentially stands in for Führer but it won't be as formalised as a form of address. That was more for you readers.

The embedded video is unavailable -- was it Marechal, nous voila?

It was something else but I have replaced it with the anthem of the new French state, Verdun, on ne passe pas!

Stifled?

On second thought that does work better.

Just looked it up in Youtube and watched what appears to be a contemporary newsreel version.

Holy sh!t! The Gallic führerprinzip !

Marechal, nous voila wasn't technically the anthem of Vichy, that remained La Marseillaise despite how out of place it was.

So the Leagues and Action France actually have a chance, then? That'll be interesting to see. I know de Gaulle had some limited sympathies with Charles Maurras when he was younger, but his personal loyalties to Petain will probably stop him from going any further.Ultimate authority resides with him but the regime won't rely on rule by decree in the same way Vichy did. There will be a constitutional convention to decide upon the nature of the new regime and in that the far-right parties will have a lot of influence. There will be some ministerial appointments as well.

You're so thoughtful.Kinda, Chef essentially stands in for Führer but it won't be as formalised as a form of address. That was more for you readers.

Can't tell if I should be excited or just bitterly amused, since the Petain regime isn't even going to outlive the decade. Wonder what they do to become famous/infamous before then.

If France gets overrun I wonder if Petain can retreat the colonies

His motivation was largely based upon preventing that in the first place.

So the Leagues and Action France actually have a chance, then? That'll be interesting to see. I know de Gaulle had some limited sympathies with Charles Maurras when he was younger, but his personal loyalties to Petain will probably stop him from going any further.

Yep. Petain's in charge and his personal popularity provides a lot of legitimacy for the regime but it's clear to everyone involved that they'll inherit a regime without him sooner rather than later so there's a lot of drive for each group to try and stamp their identity on the new regime as well as to put themselves in a good position for what form it will take post-Petain.

You're so thoughtful.

I do try!

Can't tell if I should be excited or just bitterly amused, since the Petain regime isn't even going to outlive the decade. Wonder what they do to become famous/infamous before then.

It'll last longer than Vichy did at any rate.

Fucking up on Germany seems quite likely, seeing as how Hitler manages to pivot directly from civil war into kicking ass, they must of done it quite spectacularlyCan't tell if I should be excited or just bitterly amused, since the Petain regime isn't even going to outlive the decade. Wonder what they do to become famous/infamous before then.

Mmm, so longer than around 4 years give or take.It'll last longer than Vichy did at any rate.

Chapter CXVI

Why is it that in Russia in 1917 the bourgeois-democratic February Revolution was directly linked with the proletarian socialist October Revolution, while in France the bourgeois revolution was not directly linked with a socialist revolution and the Paris Commune of 1871 ended in failure? Why is it, on the other hand, that the nomadic system of Mongolia and Central Asia has been directly linked with socialism? Why is it that the Chinese revolution can avoid a capitalist future and be directly linked with socialism without taking the old historical road of the Western countries, without passing through a period of bourgeois dictatorship? The sole reason is the concrete conditions of the time. When certain necessary conditions are present, certain contradictions arise in the process of development of things and, moreover, the opposites contained in them are interdependent and become transformed into one another; otherwise none of this would be possible.

Such is the problem of identity. What then is struggle? And what is the relation between identity and struggle?

~ Mao Zedong, On Contradiction

Such is the problem of identity. What then is struggle? And what is the relation between identity and struggle?

~ Mao Zedong, On Contradiction

Ludwigsplatz, Saarbrücken; February 1934

Ludwigsplatz was named after the protestant church which sat in the centre of its square, the two having been built alongside each other.

Both the square and the Ludwigskirche had been built to glorify God but also to accommodate the growing evangelical lutheran congregation of Saarbrücken back in the eighteenth century, they also sat as a piece of art over the great changes which had taken place around them. From the French revolution to the demise of the Holy Roman Empire, from the Napoleonic Wars to the revolutions of 1848, to the wars of German unification to the war to end all wars, and the German revolution it had started. A revolution which remained unfinished.

Today the church bells rang out above the growling of tank engines which crossed the city’s many bridges to the cheers of its residents. Alongside them were the troops of the People’s Guard and there to greet them were the workers of the city, flying both the republican tricolour and flags which were entirely red. There was joy that resonated throughout the city with an evangelical vigour.

Partly it was a sense of relief, partly jubilation at the righting of wrongs imposed over a decade ago. Peter Klompf tried to remain reserved amongst them. He was here in his official role as a functionary of the National Reconstruction Council and also in his less-official role as part of the team responsible for armoured warfare development within the People’s Guard. He was here to see how the new German tanks performed in their first assignment, and more broadly how the industry of the region could assist in their progress. Nonetheless he was immersed in the joy of the people around him and it was hard not to get swept up in it all. It was a good day to be German.

This was a situation playing out throughout the Rhineland, the area bordering France and Germany which had been forcefully demilitarised since the war, but Peter believed it would be felt most poignantly here. The people celebrating around him had been removed from Germany altogether. Like the German revolution, the Saarland had also been left in an unresolved state since the war. Like the demilitarisation of the Rhineland this had been dictated by the Treaty of Versailles which had left the coal-rich industrial area under the control of the League of Nations to be exploited as reparations by the French.

Since then the League of Nations had governed the territory whilst the French loomed over it, extracting much of the wealth of the coal rich industrial region to the resentment of the locals. Their voice in these matters had been limited to a toothless regional council, which in every election saw large majorities for the parties favouring a return to Germany only for these requests to be ignored. This state of affairs had been endured by the local populace for 14 years and per the stipulation of the Treaty of Versailles it had been supposed to last another year where the future of the basin would then be decided by a referendum.

This was now being cut short.

Events in France over the past week had provoked a German response in the name of maintaining their frontier, including the Saarland. The French military had briefly occupied the area during the civil war only to grudgingly withdraw upon the agreement of the League of Nations sponsored cease-fire. They had claimed their right to renew their occupation ever since and the installation of a military government in Paris who had cast no illusions towards the enmity for Germany made the risk of the region once again being occupied untenable.

The People’s Guard had marched in within days of the events in Paris, despite the League’s protests. The governors of the territory continued to argue about violations of the treaty but the regional council had given their blessing to the occupation and the regional police were now actively assisting their fellow Germans. These men were not necessarily revolutionaries but happy to cause a fuss, they had little sympathy with the League-appointed governors by this point. The civilian response had been one of celebration and relief as news across the border continued to worsen.

An outbreak of rioting in Paris had been merely the first step in a right-wing takeover of France led by Maréchal Philippe Pétain. First the French military and their newfound allies in the fascist leagues had taken control of the capital, then mobilised to do the same throughout the country. Without a decade of military restrictions they had accomplished this task far more handily than the Reichswehr had attempted and in Pétain they had a leader who was able to quell many suspicions of otherwise democratically minded Frenchmen. He had justified his takeover of the country by condemning the supposed corruption and incompetence of the republic and had included in this a tirade about their inability to quell a resurgent Germany.

News of a general strike and widespread factory occupations had followed but it appeared the French working class had been caught out disunited and disorganised. There were reports of riots throughout the country but no coordinated armed uprising so far. It seemed that France was doomed to fall to fascism, leaving Germany encircled.

Within hours of Pétain’s speech in Paris, the People’s Guard had mobilised. In the months Peter had spent back and forth between Germany and the Soviet Union he had overheard talk of plans to rapidly reoccupy the Rhineland had a French invasion appeared imminent. The People’s Guard remained a poor match for the French but Germany was not as helpless as it had been in 1923 when the French had been able to occupy the Ruhr without fear of military resistance. Peter hadn’t been privy to the details of such plans but it appeared the new armoured force he was helping to organise and produce had been included in them for now here he was, along for the ride.

Peter liked to think the armour had made an impression of its own, enough for the outside world to know that Germany meant business and for the French to realise that any moves on their own part might be mistaken. They were Soviet models produced under licence in German factories but that was only a stepping stone. If more time could be bought then a new generation of German tanks could truly threaten the old enemy rather than just frighten them.

That was as patriotic a stance he could have made and Peter couldn’t help but feel how his mother and father would be reacting to these events. They wouldn’t know his role in them of course, if they had he wasn’t doing his job properly, but perhaps they would consider that the cause their son had embraced had done some good for Germany.

Peter’s thoughts of family drifted away from him as he spotted a recognisable face in the crowd. Someone was happy to see him here after all.

From the opposite side of the square stood Klaus, Peter’s friend since their first stint in Russia. In a way it was Klaus he had to thank for leading him away from the Reichswehr and towards this brighter path, even if Klaus himself had embraced it with a greater deal of enthusiasm. He was wearing a new People’s Guard uniform but still looked immaculate in it, disappearing in and out of sight. It became clear Klaus was motioning for Peter to come with him and Peter hesitantly went along. The League of Nations had eyes here after all.

Klaus led him down a number of streets and Peter followed, wary of not being seen in connection with his friend but now also wary of losing him altogether in the celebrating crowds. Eventually, he saw Klaus enter a small cafe from the side entrance. Peter paused before it and lit a cigarette, contemplating the exterior of the place.

It had clearly seen better days and the posters outside the window decried the global depression they claimed that Germany had recovered from whilst the Saarland remained detached and poverty stricken. At least today it was doing a good trade with people keen to celebrate having filled it like most other bars and cafes within the city. To get in through the front Peter would have had to squeeze past revellers eating cake in the doorway but he surmised that wasn’t why Klaus had opted for the different door. He stubbed out his cigarette on the pavement slabs and went in by the same route.

Finding himself in the kitchen, Peter was pointed to a small office that, after making his way through the clatter of the busy shift, might usually have belonged to the owner or manager. They had apparently made themselves scarce in favour of the People’s Guard officer who was now sitting behind the desk impatiently before lightening up at the sight of Peter.

“I thought you might have lost me!” Klaus exclaimed, the two friends embraced.

“You’re a colourful dog in that uniform, it would have been hard to avoid seeing you.”

“Well, there are going to be a good many more People’s Guard officers around these parts from now on. You could still be one of them, if you wanted.”

Peter waved his hand dismissively whilst they sat down, but not before Klaus closed the door to keep the kitchen noise out.

“My role in the revolution is in reconstruction, even if that has left me well acquainted with my old profession, Captain.”

“It’s Major now, actually,” Klaus replied proudly, pointing to the orange bars on the side of his sleeve. There was a small orange star above them. Peter still wasn’t fully fluent in the new iconography the People’s Guard were in the process of adopting, but he congratulated his friend all the same.

“Well then, Major, I’m happy where I am although I do feel like I could get exposed here regardless of how cloak and dagger we’re being.”

“My dear Klompf, in the past week we have revealed to the world that we are rearming, all the whilst remilitarising the Rhineland and retaking the Saar basin, tearing up the treaty of Locarno in the process. There are alarm bells ringing around the globe and we’ll be lucky not to be thrown out of the League of Nations and have the Social Democratic cowards at our throats. And, through all of this, your primary concern is keeping the collusion between the People’s Guard and the National Reconstruction Council quiet?!”

“I can’t do anything about those other matters,” Peter shrugged, “but keeping that liaison quiet is my responsibility.”

Klaus had seemed exasperated when asking the question but he was calm now.

“Good.”

He looked to the dulled clatter from the kitchen before moving in conspiratorially.

“This establishment is run by good comrades but what I was looking to speak to you about isn’t for their ears.”

Peter leaned back in his chair, it felt uncomfortable all of a sudden. Klaus beckoned him to come close to him again.

“We’ve been good at being furtive for some time, you and I. We risked a lot to hold our reading group at Kama but we did it anyway because it was the right thing to do. And when the time came, it might have saved our lives.”

“It got us through the civil war,” Peter admitted, “but my family…” He thought back to Munich, to the Bavarian independence referendum.

“You’re not the only one who’s had to make such a sacrifice,” Klaus stated hesitantly, “in fact I’d go as far as to say that every true revolutionary has found themselves losing people thanks to ideological convictions.”

“Or their own lives,” Peter added half-jokingly.

“But we’re alive, and your performance has been exemplary in your role. You’re composed, professional and dedicated to our cause. And that’s why I’ve been asked to involve you in more work.”

“Party work? You do realise I’m not actually a member of the KPD.” Peter was flattered by Klaus’ praise for his professionalism but it was that ethos which had kept him from actually joining any political party, regardless of his sympathies. This didn’t seem to phase Klaus however.

“I’m talking about the Red Front.”

The Red Front. It was an organisation Peter had become aware of by reading Hitler’s book together with Klaus and the other members of their reading circle. Those who had fought the French when Germany didn’t have any tanks, and had been the basis for the army that now did.

“Surely that’s before our time?”

“There are those who are still fond of that spirit within the party, they were interested in me and now they’re interested in you too.”

Peter smirked at that.

“I’m not sure beige suits me.”

“I’m not talking about bashing heads and selling newspapers!” Klaus scoffed, his exasperated tone seemed real this time.

“I’m talking about a specialist organisation of professional men and women dedicated to advancing the revolution to its final conclusion, and the elimination of any traitors and wreckers we find along the way. First in Germany and then across Europe.”

Peter wasn’t used to this sort of passion from Klaus but the way he had spat out the word ‘traitor’ reminded him of the way the charge had been levied at both of them in the forests outside Lehrte.

“And who are the traitors in all of this? Zeigner?”

“Comrade Zeigner’s role in the revolution is important but there are others in his party I am referring to. I wasn’t joking about the cowards in the Social Democrats, those who are wedded to the years of toadying to capitalists and foreign powers; they could be dangerous now we’re casting those concerns aside to complete the work of Liebknect and Luxemburg.”

“I thought Hitler and Zeigner wanted you all to be one big happy family.”

“Some of us do.” Klaus paused before suddenly correcting himself. “I do, I mean. Some of us feel we’d be betraying our principles but they can be argued down. Some in the SPD also believe it would be a betrayal of their principles, however their principles consist of serving capitalism as a bourgeois liberal party for the rest of their days. We don’t want to argue with them, we’d want them gone for good.”

“Even if some can be brought round?”

“That could come later.” Klaus mumbled before his smile returned. “But what about you my dear Klompf? Shall we work on the revolution together once more?”

Peter could only shake his head, looking back to the closed door.

“Well if that can come later, let me come to you when I’m ready. Until then,” Peter rose from his seat.

“I’m staying above ground.”

Klaus looked disheartened but he didn’t lose his composure this time.

“It was worth a try my friend, whenever you’re ready please do get in touch. Until then, I hope we won’t fall out over all this?”

Peter shook his head once more but he couldn’t find it in him to smile.

“The thought never crossed my mind.”

Peter left the cafe to return to the celebrations outside, he had a job to do after all.

Amongst the crowds, the revolution felt much more alive than it had inside the manager’s office.

---

The painting is Forging the Scythes by Wojciech Fangor

Ein bisschen bedrohlich. From the phrasing and the track records of both historical socialist regimes and Hitler, I'm interpreting this information as 'we're making a friendlier-sounding Stasi.' Is the Rotfront going to be the DAR (and presumably German-occupied Europe's) secret police, then?“I’m not talking about bashing heads and selling newspapers!” Klaus scoffed, his exasperated tone seemed real this time.

“I’m talking about a specialist organisation of professional men and women dedicated to advancing the revolution to its final conclusion, and the elimination of any traitors and wreckers we find along the way. First in Germany and then across Europe.”

Share: