Weird, messy European elections have become as much a part of European politics as elections themselves. So it says a lot that even by those standards, the 2021 German federal election has been weird and messy. For a start, the result was guaranteed to be interesting given that Angela Merkel retired as Chancellor after sixteen years and no incumbent Chancellor would be running, the first time in post-war German history this has been the case.

But instead of Merkel’s absence giving her CDU/CSU an opportunity for a new lease of life, the party has been mired in conflicts. The CDU leadership contest in 2018 saw former the party’s General Secretary and former Minister-President of Saarland Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer (commonly known by her initials AKK), perceived as an heir to Merkel, defeating the more conservative former Bundestag leader Fredrich Merz. One of AKK’s main assets was that, despite her social conservatism, she was seen as more moderate and likely not to rock the boat; she demonstrated during the 2019 EU Parliament elections that this was not the case with a rather ham-fisted push for electoral law to reduce the ability of social media personalities to influence voter choices after a popular YouTuber called Rezo put out a video aggressively critiquing the CDU/CSU, SPD and AfD.

This fiasco and reporting that Merkel did not think AKK was up to the job of Chancellor weakened her, but her failure to discipline the Thuringia CDU for voting with the AfD for the election of Thomas Kemmerich as the state’s Minister-President in February 2020 was the last straw. When AKK announced she would resign as CDU leader, the leadership race was expected to be held in the summer, but ended up being postponed until the start of 2021 thanks to COVID-19.

That race led to the election as CDU leader of North-Rhine Westphalia Minister-President Armin Laschet, also a social conservative (like AKK he opposed gay marriage, but tapped the gay Health Minister Jens Spahn to serve as his deputy) and economic moderate who is ideologically close to Merkel. Laschet faced a challenge by Markus Söder of the CSU, and the two of them failed to agree between themselves who should be Chancellor candidate, forcing the federal board to break the deadlock and make Laschet party leader.

Something just as interesting has happened on the opposition side during 2021. Thanks to fatigue with the grand coalition and the general rise in awareness of the severity of climate change, the Greens managed during April and May to overtake the CDU/CSU for first in the polls, and rather than retaining the dual leadership it, Die Linke and the AfD have traditionally practiced, it picked a Chancellor candidate for the first time, Annalena Baerbock.

But the really odd thing to happen concerns the CDU/CSU’s longtime coalition partner. The SPD, which has spent all but four of the last 23 years as a part of Germany’s federal government and spent the 2010s as a poster child for Pasokification, has managed with its Chancellor candidate, Vice Chancellor and former Mayor of Hamburg Olaf Scholz, to capitalize on the fractious nature of the conflict. With Laschet and the CDU/CSU seen as burnt out and divided and Baerbock and the Greens as too inexperienced for government, Scholz benefitted both from his slightly more left-wing campaign promises like raising the minimum wage from €9.60 to €12 and improving the affordability of housing and from his perceived closeness to Merkel on issues like national and European leadership.

Mostly thanks to Scholz’s presence, the SPD moved to a consistent lead in the polls during late August and early September, but its lead tightened towards the end of the campaign, likely due to closer scrutiny of Scholz’s past (I read quite a scathing article about it in Politico a week or so ago) and Merkel finally giving her endorsement to Laschet. The exit polls showed a neck-and-neck race between the two main parties, but by the closest margin since 2005 and for the first time since 2002, the SPD emerged as the largest party in the Bundestag with (as of this writing) a projected 206 seats while the CDU/CSU came out with just 196 seats, its worst result ever.

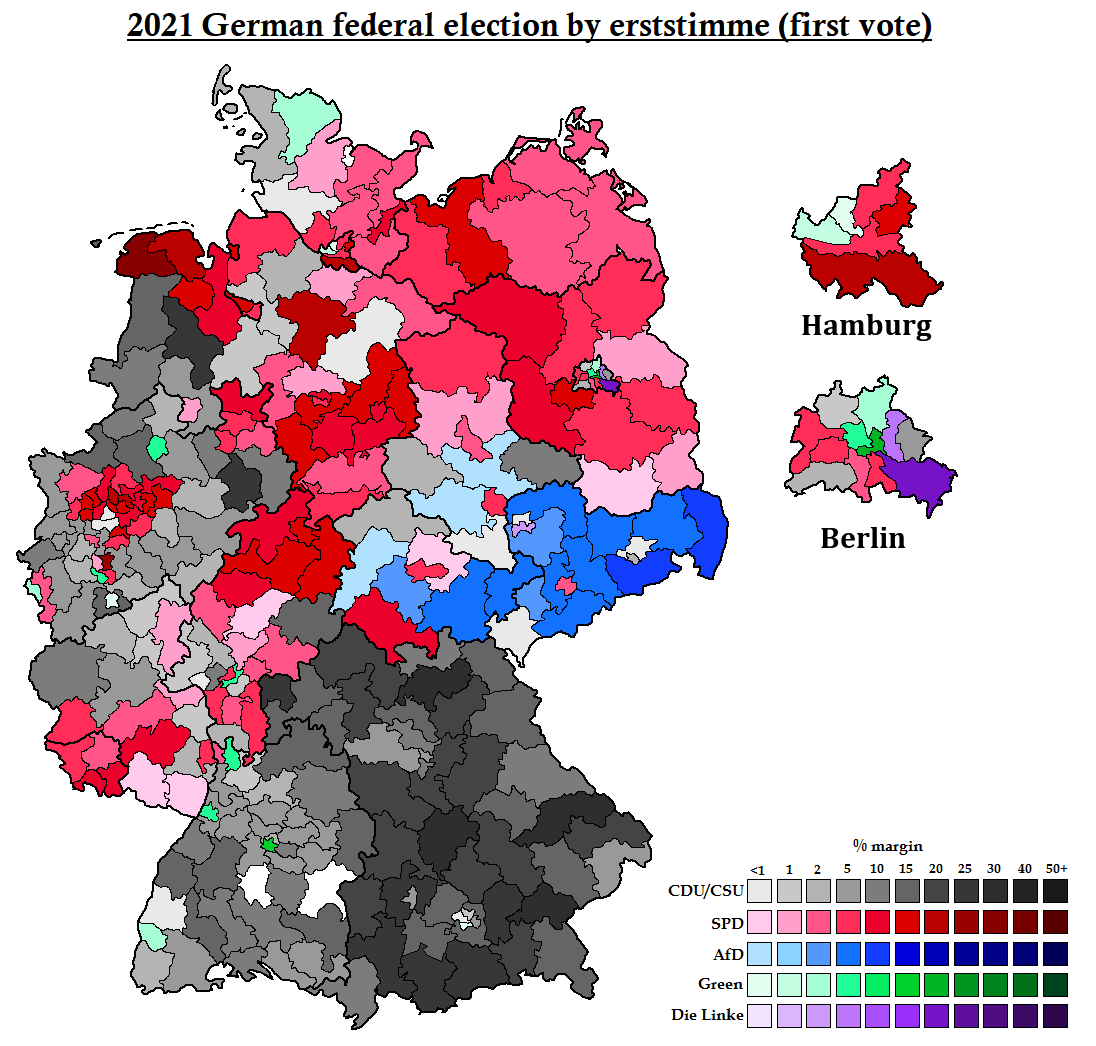

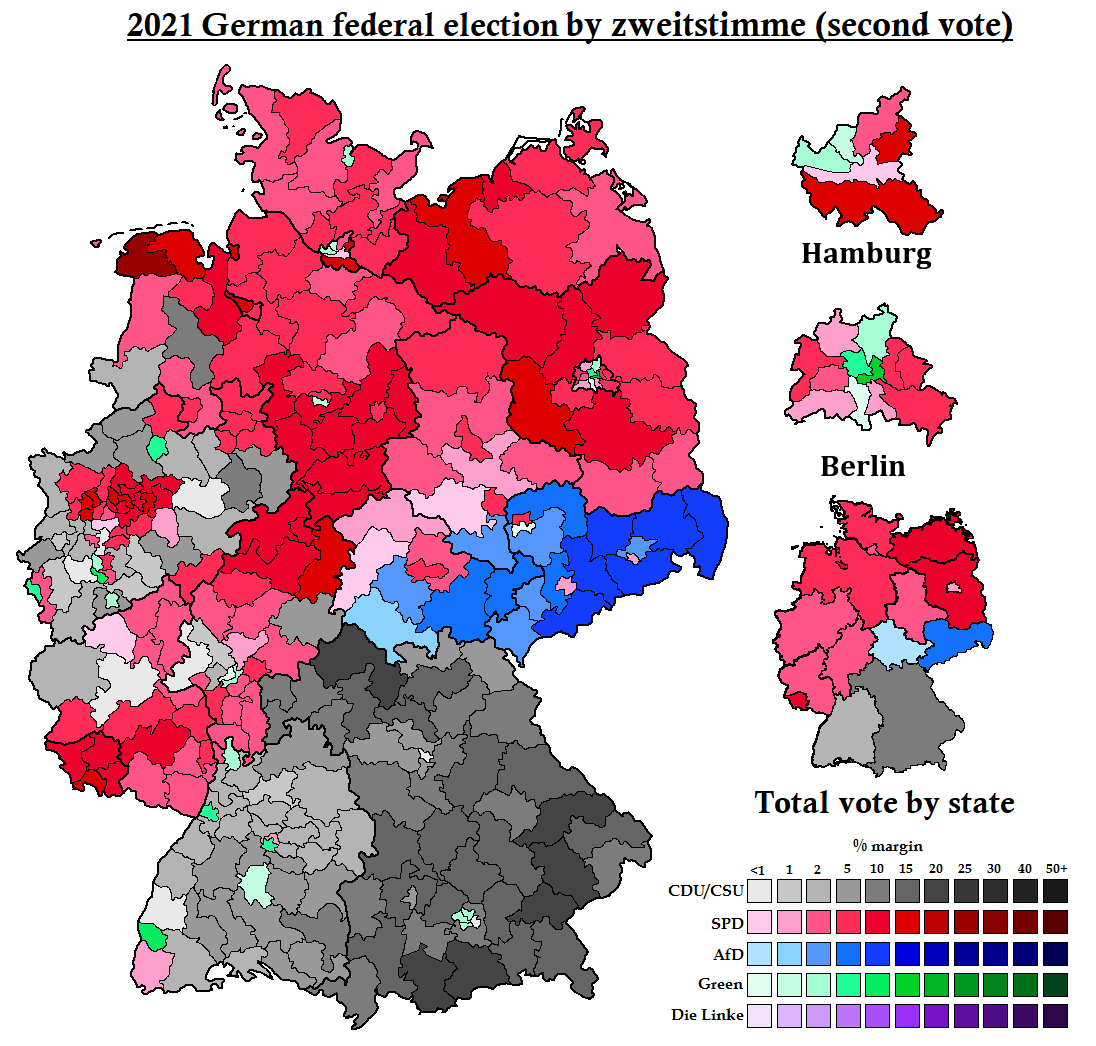

It’s probably accurate to say the 2021 election was a vote against both the major two parties to a significant degree, though. Though they didn’t do as spectacularly as they’d hoped earlier in the year, the Greens got their best result ever and broke 100 seats for the first time (coming in at 118) and won their first FPTP district outside of Berlin (their first eleven, actually!) and the FDP took 92, their best total since 2009. More concerningly, the AfD took sixteen FPTP districts, all in the East, and topped the polls for the PR vote in Saxony and (just barely) in Thuringia. Ironically they actually lost 11 seats due to their vote declining overall across the country. Die Linke were badly hurt by the surge of the bigger left-wing parties, falling to 4.9% of the vote and just barely re-entering the Bundestag thanks to winning three seats (they lost an East Berlin district to the CDU of all parties though).

The East-West divide is still very prominent, which is probably unsurprising in German politics at this point- as mentioned, in the West the Greens made unprecedented gains and the AfD did the same in the East, but the SPD also achieved a striking recovery in the East, going from holding two seats across all of the former East Germany (one in East Berlin and one in Potsdam, the latter electing Scholz this year) to twenty-seven, more than any other party. The one which really grabbed people’s attention was Vorpommern-Rügen-Vorpommern-Greifswald I, Merkel’s old district, going red as every FPTP seat in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern and Brandenburg went to the SPD, which they didn’t even manage in 1998.

In terms of raw votes, though, initial analysis suggests the more fundamental division now is one of age. Apparently older voters whose cleavages between the CDU/CSU and SPD are well-established stayed that way, while younger voters went to the Greens and FDP and middle-aged voters were more likely to break for the AfD.

Now that the results have come in, of course, comes the agonizing process of coalition-building. The smart money is on either a traffic light coalition (SPD, Greens and FDP) or a Jamaica coalition (CDU/CSU, Greens and FDP); the numbers would allow for either, with the Greens being more inclined to work with the SPD and the FDP more inclined towards the CDU/CSU. Both leaders have more-or-less ruled out another grand coalition (then again, they did that in 2005 and 2017…) and are settling in for hard negotiations, though of course Merkel will stay in place until a new Chancellor is elected by the Bundestag. Probably the most apt comment I’ve seen is someone who said the real negotiations will be between the FDP and Greens.

Anyway, now I’ve done that long as hell write-up to contextualize it, here are the maps I made of the eststimme (‘first vote’, for the FPTP districts) and zweitstimme (‘second vote’, for the PR lists in each state, though they’re counted by district as well). Credit for the basemap goes to Oryxslayer, though I made a few amendments to account for boundary changes and my format is based on majorities rather than voteshare.

But instead of Merkel’s absence giving her CDU/CSU an opportunity for a new lease of life, the party has been mired in conflicts. The CDU leadership contest in 2018 saw former the party’s General Secretary and former Minister-President of Saarland Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer (commonly known by her initials AKK), perceived as an heir to Merkel, defeating the more conservative former Bundestag leader Fredrich Merz. One of AKK’s main assets was that, despite her social conservatism, she was seen as more moderate and likely not to rock the boat; she demonstrated during the 2019 EU Parliament elections that this was not the case with a rather ham-fisted push for electoral law to reduce the ability of social media personalities to influence voter choices after a popular YouTuber called Rezo put out a video aggressively critiquing the CDU/CSU, SPD and AfD.

This fiasco and reporting that Merkel did not think AKK was up to the job of Chancellor weakened her, but her failure to discipline the Thuringia CDU for voting with the AfD for the election of Thomas Kemmerich as the state’s Minister-President in February 2020 was the last straw. When AKK announced she would resign as CDU leader, the leadership race was expected to be held in the summer, but ended up being postponed until the start of 2021 thanks to COVID-19.

That race led to the election as CDU leader of North-Rhine Westphalia Minister-President Armin Laschet, also a social conservative (like AKK he opposed gay marriage, but tapped the gay Health Minister Jens Spahn to serve as his deputy) and economic moderate who is ideologically close to Merkel. Laschet faced a challenge by Markus Söder of the CSU, and the two of them failed to agree between themselves who should be Chancellor candidate, forcing the federal board to break the deadlock and make Laschet party leader.

Something just as interesting has happened on the opposition side during 2021. Thanks to fatigue with the grand coalition and the general rise in awareness of the severity of climate change, the Greens managed during April and May to overtake the CDU/CSU for first in the polls, and rather than retaining the dual leadership it, Die Linke and the AfD have traditionally practiced, it picked a Chancellor candidate for the first time, Annalena Baerbock.

But the really odd thing to happen concerns the CDU/CSU’s longtime coalition partner. The SPD, which has spent all but four of the last 23 years as a part of Germany’s federal government and spent the 2010s as a poster child for Pasokification, has managed with its Chancellor candidate, Vice Chancellor and former Mayor of Hamburg Olaf Scholz, to capitalize on the fractious nature of the conflict. With Laschet and the CDU/CSU seen as burnt out and divided and Baerbock and the Greens as too inexperienced for government, Scholz benefitted both from his slightly more left-wing campaign promises like raising the minimum wage from €9.60 to €12 and improving the affordability of housing and from his perceived closeness to Merkel on issues like national and European leadership.

Mostly thanks to Scholz’s presence, the SPD moved to a consistent lead in the polls during late August and early September, but its lead tightened towards the end of the campaign, likely due to closer scrutiny of Scholz’s past (I read quite a scathing article about it in Politico a week or so ago) and Merkel finally giving her endorsement to Laschet. The exit polls showed a neck-and-neck race between the two main parties, but by the closest margin since 2005 and for the first time since 2002, the SPD emerged as the largest party in the Bundestag with (as of this writing) a projected 206 seats while the CDU/CSU came out with just 196 seats, its worst result ever.

It’s probably accurate to say the 2021 election was a vote against both the major two parties to a significant degree, though. Though they didn’t do as spectacularly as they’d hoped earlier in the year, the Greens got their best result ever and broke 100 seats for the first time (coming in at 118) and won their first FPTP district outside of Berlin (their first eleven, actually!) and the FDP took 92, their best total since 2009. More concerningly, the AfD took sixteen FPTP districts, all in the East, and topped the polls for the PR vote in Saxony and (just barely) in Thuringia. Ironically they actually lost 11 seats due to their vote declining overall across the country. Die Linke were badly hurt by the surge of the bigger left-wing parties, falling to 4.9% of the vote and just barely re-entering the Bundestag thanks to winning three seats (they lost an East Berlin district to the CDU of all parties though).

The East-West divide is still very prominent, which is probably unsurprising in German politics at this point- as mentioned, in the West the Greens made unprecedented gains and the AfD did the same in the East, but the SPD also achieved a striking recovery in the East, going from holding two seats across all of the former East Germany (one in East Berlin and one in Potsdam, the latter electing Scholz this year) to twenty-seven, more than any other party. The one which really grabbed people’s attention was Vorpommern-Rügen-Vorpommern-Greifswald I, Merkel’s old district, going red as every FPTP seat in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern and Brandenburg went to the SPD, which they didn’t even manage in 1998.

In terms of raw votes, though, initial analysis suggests the more fundamental division now is one of age. Apparently older voters whose cleavages between the CDU/CSU and SPD are well-established stayed that way, while younger voters went to the Greens and FDP and middle-aged voters were more likely to break for the AfD.

Now that the results have come in, of course, comes the agonizing process of coalition-building. The smart money is on either a traffic light coalition (SPD, Greens and FDP) or a Jamaica coalition (CDU/CSU, Greens and FDP); the numbers would allow for either, with the Greens being more inclined to work with the SPD and the FDP more inclined towards the CDU/CSU. Both leaders have more-or-less ruled out another grand coalition (then again, they did that in 2005 and 2017…) and are settling in for hard negotiations, though of course Merkel will stay in place until a new Chancellor is elected by the Bundestag. Probably the most apt comment I’ve seen is someone who said the real negotiations will be between the FDP and Greens.

Anyway, now I’ve done that long as hell write-up to contextualize it, here are the maps I made of the eststimme (‘first vote’, for the FPTP districts) and zweitstimme (‘second vote’, for the PR lists in each state, though they’re counted by district as well). Credit for the basemap goes to Oryxslayer, though I made a few amendments to account for boundary changes and my format is based on majorities rather than voteshare.

Last edited: