You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Osman Reborn; The Survival of Ottoman Democracy [An Ottoman TL set in the 1900s]

- Thread starter Sarthak

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 110 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Holidays in the Ottoman Empire Chapter 66: The Swedish Republic of Ostrobothnia & Growing Disillusionment Look into the future [4] Chapter 67: cultural update – The Top 3 Sports in the Ottoman Empire turtledoves 1926 Ottoman General Elections Map. Chapter 68: African Rumblings. Chapter 69: Land of the UnfreeThe Weavers (1905), by the Manaki brothers, was the first film made in the Ottoman Empire. The earliest surviving film made in what is present-day Turkey was a documentary entitled Ayastefanos'taki Rus Abidesinin Yıkılışı (Demolition of the Russian Monument at San Stefano), directed by Fuat Uzkınay and completed in 1914. The first narrative film, Sedat Simavi's The Spy, was released in 1917. Turkey's first sound film was shown in 1931

Cinema of Turkey - Wikipedia

Cinema in Turkey truly became a more common thing in the 50s.

Last edited:

Chapter 65: The Balkan Three

Chapter 65: The Balkan Three

Greece by the end of the first half of the 1920s was a changing nation. For sixteen years, Greece had been under the premiership of Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos, a man whose political acumen and leadership had carved himself a name in the history of Greek and Balkan politics. However, even as Venizelos’s successes remained great, his political opponents were moving against him as the 1926 Legislative Elections came forward. Venizelos had ruled uninterrupted for sixteen years and political fatigue became a huge problem for Venizelos as his opponents were gradually becoming more and more popular with the general population. The United Opposition had fallen apart after the 1922 Legislative Election failed to secure a victory, however as Panagis Tsaldaris retreated from the leadership of the People’s Party and allowed veteran politician Dimitrio Goundaris to retake power as leader of the party, the People’s Party had experienced a massive revival, and local municipal elections throughout Greece saw a large amount of politicians from the People’s Party take power. The endorsement of powerful leaders such as Xenophon Stratigos and Nikolaos Stratos to the People’s Party only added to the general popularity of the People’s Party. Other Anti-Venizelists, such as Ioannis Metaxas and Alexandros Paanastasiou continued to increase their own political influence and power as well.

Venizelos

The Greek Political Legend

But perhaps the greatest problem that of Italy. Italy under the collective leadership of Antonio Gramsci and his allies in the Italian Communist Parliament was starting to recover from its economic and military defeats in the First Great War and subsequent Italian Revolution. Gramsci was instead driving Italy forward with the focus on industrialization, procreation, and militarization leading to Italy having a much stronger position than it enjoyed half a decade earlier, and Gramsci was eager to build up Italian influence beyond its own borders through the means of economic investments. Gramsci first offered Greece economic investments in 1924 which Venizelos rejected, as he was still wary of the new regime in Rome, and the Greek Conservatives would have been furious if he accepted an investment offer from a communist nation instead. King George II was also hesitant of an economic relationship between Athens and Rome, and thus that killed any sort of ideas of Italian investments for the time being. But Gramsci was not deterred and soon, more and more tempting economic offers from Rome found themselves on the desk of the Greek Prime Minister and finally on the 12th of January, 1926, Venizelos was tempted beyond his limits and allowed 6 Italian factories to be opened up in Thessaly and Greek Epirus in return for a large 45% royalty sum to the Greek government, which was an extremely beneficial deal economically. Yet, it outraged the conservative People’s Party and even the left-wing Agricultural and Labour Party was wary of the idea and tepidly warned against it. War with Italy was a question that had burned hard in Greece since the early 1900s, ever since Italy’s Mediterranean Ambitions cropped up after 1902. The new Communist Regime in Italy had certainly inherited said dreams and many in Greece were fearful of war with Italy. Major General Nikolaos Trikoupis, the Military Commander of the Corfu Military District warned Athens that Greece had to prepare for eventual war with the Italians, which he deemed inevitable as the Communists continued to engage in intrigues in Greece.

Venizelos was also getting old by that point, and even his own son, Sofoklis Venizelos, was getting rather concerned about Greece’s preeminent Prime Minister who was suffering from more and more health problems as time rolled by. Finally, after suffering a stroke on the 29th of January, 1926, Venizelos decided that he would retire from politics and his occupation and gave up the position of Prime Minister of Greece to his capable Finance Minister, Georgios Kafantaris. Kafantaris became Prime Minister of Greece on the 31st of January, 1926 and he was more than capable of understanding the difficulties that Greece was about to face. Italy was a prime concern for the Greek Prime Minister, and furthermore, Serbia was also becoming a concern for the new government in Athens. Britain’s lukewarm attitude towards Greece after the Great War due to a successive amount of inward looking British Prime Ministers meant that Britain could no longer be trusted with securing the territorial integrity of the Kingdom of Greece, which was becoming warier and warier of Rome and Belgrade as successive economic and diplomatic dealings only furthered Athens’s apprehension. Kafantaris as such, turned to the Ottoman Empire to the east.

Georgios Kafantaris

Prime Minister of Greece (1926 - 1933)

The Ottoman Empire had stagnated from 1827 to 1908, despite the efforts of the Tanzimat to do otherwise, but the 1908 Revolution had been like a spark that had burned down the old and ushered in the new. Economically robust after the comprehensive Ahmet Riza reforms of the mid-1910s, and militarily secure after the Balkan War of 1915, the Ottoman Empire had proven itself both on the economic and military playing fields. Further, due to the 1911 Treaty of Salonika, Greece enjoyed a rather beneficial cooperative relation with the Ottoman government. The newly created Aegean Class Heavy Cruiser was made by Greece and the Ottomans in tandem with one another, already showing the capability to work together for defensive arrangements. Kafantaris, always a pragmatist at heart, was also looking favorably to the Ottomans due to the Anglo-Ottoman Alliance, which gave the government in London a duty to honor her alliance. With Britain ignoring Greece in favor of containing Russia for the time being, having a more formal allied treaty with the Ottomans was seen as a possible solution in Greece. On February 22, 1926, Kafantaris broke his idea of a formal Greco-Ottoman Alliance to secure Greece’s economic and military future to his new cabinet, which was met with mixed responses. Pragmatists were more than happy about the idea, as it gave Greece collective security beside the Ottomans, and as the economic clauses of the 1911 Treaty of Salonika were due to be terminated by the end of the month, renewing them would have been much easier if Athens and Constantinople were in formal alliance. However, old public sentiments died hard, and many were wary of an alliance with the ‘Old Enemy’ so to speak.

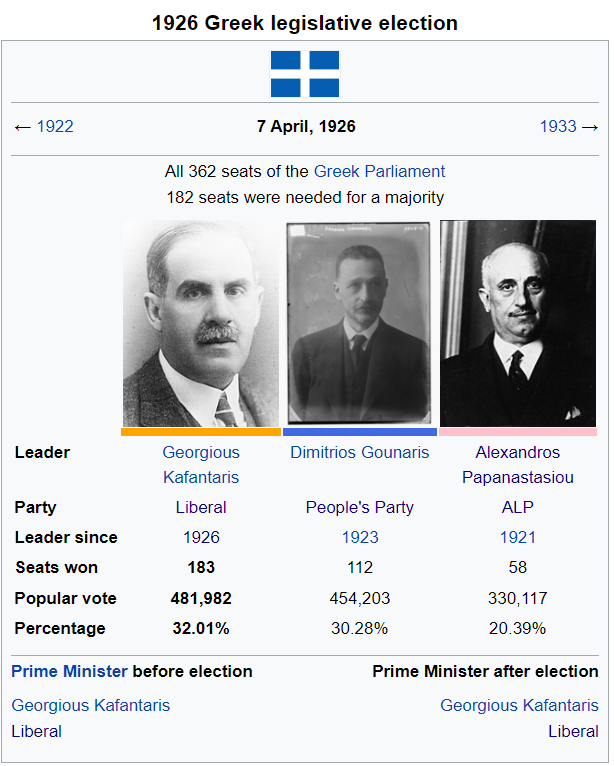

The idea soon broke into the Greek public. Crete and the Greek Peloponnese became the leaders of the anti-alliance faction in Greece, whilst Cyprus and Thessaly, both having significant Turkish and Muslim populations, became the leaders of the pro-alliance faction in Greece, whilst the other regions in Greece had their own differing ideas of such an alliance. As the new elections were called for in 1926 the idea of an alliance with the Ottoman Empire became the most heated issue in the political arena of Greece. The People’s Party led by Gounaris was vigorously opposed to the idea of an alliance with the Ottoman Empire, whilst the Agriculture and Labour Party remained neutral on the topic, instead seeking to further the rights of the common laborer and worker in the Greece rather than tackling the hot issue of an alliance. The Liberal Party instead was a pro-Alliance party, and campaigned in the promise of collective security. When it came right down to it, the Liberals and the People’s Party held an equal amount of votes, and the muslim voters of Greece became the deciders of the 1926 election in Greece. With the Muslim Greeks solidly in favor of an alliance with the Ottoman Empire, the vote turned in favor of the Liberal Party, and the Liberal Party managed to eke out a victory in the 1926 elections with a majority of 1 seat. The muslim population of Greece had become the deciding vote for the first time in Greek electoral history.

His policy vindicated through the election, Kafantaris began to prepare to lay the foundations of the infamous Greco-Ottoman Alliance.

By 1924, Bulgaria had recovered. Prime Minister Nikola Mushanov, and the Bulgarian National Recovery Coalition Union had managed to fulfill its role pretty well. Bulgaria’s economic output reached pre-1915 levels for the first time in a decade, and new industrial zones and estates meant that manufacturing was growing. Relations between Sofia and Constantinople had turned cordial with one another and the power and influence of the military, once massive, had been scaled down after Ivan Valkov’s failed coup in 1918. But, as with any successful coalition, immediately after its goals of national recovery were completed, the coalition splintered apart. The Bulgarian Agrarian National Union wanted what was essentially a Crowned Republic, which even the Constitutional Democratic Party of Bulgaria, Mushanov’s party, deemed unacceptable, and the Social Demorats under Yanko Sakazov wanted a fully-fledged republic, which was opposed by both the BANU and the Democratic Party. Danev’s Progressive Liberal Party was the only party that remained firm in its belief that the Kingdom/Tsardom of Bulgaria was there to stay.

Bulgaria in the 1920s

The 1924 Bulgarian Parliamentary Elections became a heated affair as a result of the dissolution of the National Recovery Coalition, and the result was a hung parliament as the Progressive Liberals, Radical Democrats, BANU, Democrats and Social Democrats received a near equal amount of seats in the Bulgarian National Assembly as each party received a number of seats between 40 to 50 in a legislature which contained a total of 236 seats. Aleksander Stamboliyski, the leader of the BANU took advantage of the political confusion and tried to form a coalition with the Social Democrats, which fell through due to the unrepentant republican position of the Social Democrats, whilst the attempts of Mushanov to form a coalition with the Progressive Liberals and Radical Democrats fell through due to the fact that all of these political parties did not trust the other. This became known as the 1924 Bulgarian Parliamentary Crisis. With no government in power, and all of the political parties unable to work with one another, Bulgaria was effectively running without a government in 1924, and this forced King Boris III to take action.

Boris III had watched the rather weak and unstable National Recovery Coalition and the subsequent political moves with growing irritation and using the Tarnovo Constituion of 1879, dissolved the Bulgarian National Assembly on December 2, 1924 and then took near-absolute control of Bulgaria through royal decree and Articles 61 and 62 of the Tarnovo Constitution which gave the Bulgarian Tsar near absolutist powers in the case of political crisis in the Bulgarian nation. Boris III then turned and solved the political crisis in Bulgaria in the most surprising manner possible. He decreed that every political party was from December 15, 1924 onwards banned, and instead introduced a new system of non-partisan parliamentary democracy. Mushanov’s position as Prime Minister was then removed and Mushanov, caught off guard by the wily king’s virtual coup de etat, resigned from politics, and the position of Prime Minister of Bulgaria was then offered to General Vladimir Vlazov, one of the few successful Bulgarian generals of the Balkan War and a firm royalist. He was also the Mayor of Sofia from 1919 to 1923, in which role he successfully modernized the capital of Bulgaria. Vazov accepted the offer and became the next Prime Minister of Bulgaria, ending the 1924 Bulgarian Parliamentary Crisis.

Boris III was essentially trying to create a new regime of democratic, yet royalist (with significant powers to the monarch) ideals. This proved to be a hard thing to conduct. Vazov had proven himself to be a capable administrator during his time as the Mayor of Sofia, and this showed through his immediate actions upon taking the office as Prime Minister. He approved several new land laws, and the economic and commercial requests that were pending due to the governmental crisis were immediately looked after by Vlazov’s new cabinet, which itself was appointed quickly to avoid further delays in governmental capability. Vazov’s appointment had been a smart choice, but the two powerful personalities were not sure how to create their shared vision of a democratic yet royalist regime in Bulgaria. While no formal idea was produced, this vision eventually led to what became known as the ‘Boris-Vlazov’ system. This system was in essentiality, a puppet cabinet and a puppet government whenever Boris III wanted something done, yet a democratic and accountable government when Boris III decided not to interfere personally. And the first time this was used was in early 1925, when Vlazov made it clear to Boris III that he wanted to remove the influence of the Bulgarian military in politics, which still lingered, despite the attempted coup of 1918. Boris III was in favor of this policy whole heartedly and both men were blessed with good fortune in this endeavor.

Boris III appointing the new Royalist Regime in Bulgaria.

This was the Starting of Borisian Bulgaria (1924 - 1968)

Damyan Velchev was driven into exile due to his links with the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO). The IMRO, which had once been a tool of the Bulgarian government for irredentist desires had become their own enemies after the Bulgarian government failed to conquer Ottoman Slavic territories in 1915. Velchev’s influence in the army was massive, and his desire to be involved in Bulgarian politics was what partially drove the Bulgarian military to interfere with the country’s politics. HE was arrested on orders of the King, and though Vlazov was eager for the death sentence, that was commuted to life imprisonment by Boris III. Kimon Georgiev, another active military officer who was known to meddle in Bulgarian politics was removed from his post and sent into de-facto exile by becoming the Military Attaché of Bulgaria in Vienna. Velchev and Georgiev’s political military organization, the Military League was abolished, and a subsequent purge in the Bulgarian military flushed out most members of the Military League from the Bulgarian Army. This swift action by Vlazov and Boris III basically culled all the influence the army had on politics in Bulgaria, thus essentially making the army a non-existent factor in Bulgarian politics for the time being.

Boris III and Vlazov became more and more popular among the Bulgarian population as time went by, despite the misgivings of the general populace towards the new pro-royalist government and non-partisan regime. Boris III continued Mushanov’s policy of rapprochement with the Ottoman Empire, and the Kingdom of Greece, which saw Ottoman aristocrats being able to buy estates and invest into the Bulgarian industrial economy for the first time since 1881. It also saw the marriage of King Boris III with Prince Olga of Greece. Since 1922, during a small visit to Greece, Boris III’s attention had been caught by the daughter of Prince Nicholas of Greece and Grand Duchess Elena Vladimirovna of Russia. Considered to be one of the most beautiful princesses of the time, Princess Olga was initially indifferent to Boris III’s attempts to court her, partially due to her misgivings regarding the fact that Boris III was nearly a decade older than her. However, Boris III’s charm and charisma eventually broke through her cold exterior and the two announced their engagement in early 1924. In a ceremony partially intended to shore up support from the populace to Boris III’s new regime, a public royal wedding took place in Sofia on January 27, 1925, which saw Princess Olga of Greece become Queen Olga of Bulgaria. The marriage became a successful event, as the Bulgarian people adored their new pretty Queen. Her Bulgarian, which she spoke with a heavy Greek accent was considered humorous, and her calm exterior only served to attract more people towards her. Boris III also remained amenable and most of the public soon came to like their previously detached King. He started to drive his car through the country with no special guards around him, and often stopped to converse with the general public. During these driving sessions, he gave lifts to pedestrians in Sofia and gave several small gifts to the people he came across during these sessions. This ‘driving’ session made Boris III and his royal regime in Bulgaria much more popular than ever before.

Queen Olga of Bulgaria

Princess of Greece

Whilst Boris III took care of public matters with his new wife, Vazov got around healing the political and economic wounds of Bulgaria. The disastrous Civil War and Balkan War had led to a few years of negative population growth, and in order to combat that, the Bulgarian Prime Minister introduced several pro-natal policies by giving maternity leaves and breaks to women, and giving several tax breaks for families with pregnant women. This allowed Bulgaria, which had been registering barebone growth rates of ~0.2% since 1916 to grow towards ~1% as the result of Vlazov’s policies. The agricultural backwardness of Bulgaria, which still relied on pre-1900 equipment was addressed by the procurement of modern agricultural tools from Britain, America and the Ottoman Empire. Commercialized farming was encouraged through higher interest rates in loaned or rented out lands, and extra revenue was used in the construction and establishment of various new industrial estates, giving the Bulgarian people the much-needed employment that they desired. Adopting a paternal attitude, labour reform was passed by Vazov’s regime was well, monitoring the health and capabilities of workers in the Kingdom.

Prime Minister Vladimir Vasov of Bulgaria (1926-1938)

And though Boris III and Vlazov didn’t know it, they were laying the foundations of the Bulgarian Resistance against the Berlin Concorde during the Second Great War. Bulgaria’s resistance was crucial in the victory of the Ottoman Empire in the Balkan Front. Boris III’s royal regime survived the test of lasting more than a single year, and by 1926 the new non-partisan government chugged on, intent on modernizing the country and becoming the ideal ‘modern kingdom’.

The Romanian gains in the Balkan War had been rather small, with Romania only gaining south Dobruja from the Bulgarians, even though the Romanian territorial gains were higher in comparison to the Ottomans, who annexed a few border forts and nothing much else. Economically, Romania gained much more. The Bulgarian war reparations had basically nullified Romania’s own debt, and the freeing and demilitarization of the Bulgarian side of the Danube River had led to a significant economic boom in the region, much to the pleasure of the Romanian government. Romanian Prime Minister, Ion Bratianu, and his political party, the National Liberal Party seemed unassailable after the victory in 1915. Romania’s continued occupation of parts of northern Bulgaria until 1918 also saw Romania gain what was in their own eyes, military prestige. In spite of these victories, the failure of Romania to intervene in the Great War on either one side was seen as treasonous. Romania had been the nation to gain the most from the War, with Besserabia and Transylvania up for grabs, but the warring political factions in Romania at the time, the Conservative Party, Conservative-Democratic Party, and Democratic Nationalist Party had all been unable to reach a consensus regarding the war and had missed their chance to jump on the Great War bandwagon after Austria-Hungary left the war. There was no way Romania was going to take on Russia by itself, and the entire question and debate collapsed onto itself after Austria left the Great War.

Ethnic Map of Dobruja

Romanian nationalists had been hoping to gain either Besserabia or Transylvania, and when it was apparent that neither of them were going to be attained due to the bull headedness of the Conservative and Conservative-Democratic Party, Romanian Nationalists began to vote for the Democratic Nationalist Party, the party which had been most in favor of war during the Great War. The National Liberal Party barely managed to win the 1918 General Elections. Bratianu hoped to reinvigorate the National Liberal Party by involving itself more into social and economic matters but that idea remained unsuccessful as the Romanians were unwilling to focus entirely on the economy and social affairs. This was a bad move. Pre-1915, only 8% of Romania’s population identified as non-Romanian, but with the acquisition of South Dobruja, 15% of Romania now identified as non-Romanian, and this substantially increased minority soon became vocal in their efforts with either secession or with political representation. The Roma People, under the self-declared Gheorghe Niculescu, allied with the Ukrainian leader, Emil Bodnaras and his party, the Slavic Representation League, to demand more political and social representation and freedoms for the two minorities. Turks and Tatars in Romania also allied with Bodnaras and Niculescu, asking for greater autonomies. This alliance between the Roma, Slavs and Turks in Romania became known as the Romanian Minority Representation Association (RMRA), and the RMRA soon became a major headache for the Romanian government in Bucharest. Bulgarians from North Dobruja became involved in representation politics, whilst Bulgarians from South Dobruja became involved in secessionist affairs. And even though the regionalist and secessionist Bulgarians in Romania did not agree on the topic of regionalism or secession, they coordinated with one another politically to keep up the political pressure.

King Ferdinand I of Romania became more and more irritated with the growing political disaffection in Romania and asked (demanded) that Bratianu find a solution to the crisis. To be completely fair to Bratianu, he did create the Romanian Roma Council, a representational commission for the Romani people, and also allowed Bulgarian majority counties to be bilingual in both governmental and educational affairs, thereby diffusing ethnic tensions between the two minorities. Turks and Tatars gained an allocated amount of seats in the Romanian Chamber of Deputies (8) and Senate (3) which allowed tensions between the largest minority of the country and ethnic Romanians to die down as well. But where the ethnic minorities had started to mount political pressure on the government, the Democratic Nationalist Party picked it up and continued to create more instances of political problems in Romania. The National Liberal Party, as expected failed to gain majority in the 1922 elections and paved the way for the Democratic Nationalist Party under the leadership of Alexandru Cuza.

Cuza’s premiership was controversial. Though a social democrat in terms of economic affairs, he was a far-right politician in matters such as social lifestyle, and ethnic politics. He was also, a hard anti-semite. Being a Jew in Romania became extremely hard under his premiership, as new restraints and restrictions were imposed on the Jewish community of the nation, much to the vexation of King Ferdinand I. Cuza rejected Jews from public life, and intended to have them held up in private through internal means, diverting their needs and wants to other things. This led to much annoyance in the Romanian Jewish population and the more outraged Jewish families simply bought immigration tickets and immigrated to Austria/Danubia, Bulgaria or the Ottoman Empire, all of which were far more pro-Jewish states. Cuza, also an avowed prohibitionist passed several dry laws that made millions of Romanians to become criminals overnight (even though very few of them {a couple hundred} were ever prosecuted for breaking the dry laws). But his most controversial policy was the creation of the Jewish Quota Bill in 1923 that intended to keep a Jewish quota on everything, such as education, banking, land ownership etc. It was the last straw and pro-semites throughout Romania took the striking against the bill. Even many members of the Democratic Nationalist Party came out against the idea of the Jewish Quota, yet Cuza remained stubborn and was unwilling to negotiate or compromise. This saw King Ferdinand I dismiss Cuza from the premiership and appointed Alexandru Averescu, a more moderate member of the Democratic Nationalist Party, as the new Prime Minister of Romania.

Romania in the 1920s

Averescu was a reactionary and far-right politician himself (though he was neutral on the Jewish Question unlike his far-right colleagues), but what set the man apart from his colleagues was that the man was cunning, devious and pragmatic. A dangerous combination in politician. Averescu’s first move was to remove the Jewish Quota Bill and he also reversed the Jewish restrictions and limitations introduced by Cuza. A prohibitionist himself, he did not remove the dry laws, but he did remove the more severe penalties of breaking them. Averescu’s next line of policy was seen when he cracked down on the various communist and left-wing groups operating in Romania. Born out of his fear of the Italian Revolution and the Italian Communists, Averescu banned several left-wing parties, only allowing center-left political parties to remain legal in the country. Averescu was willing to stop there, but the more zealous members of his cabinet, such as Constantin Argetoianu, went further and conducted several arrests of left-wing politicians. Averescu and his close allies in cabinet were not even informed of the arrests taking place until Averescu noticed that several previous members of the Chamber of Deputies and Senate were missing when he proposed a new economic stimulus bill in 1924. It was basically fait accompli on part of Argetoianu’s part, but Averescu was furious and had Argetoianu himself arrested and thrown into prison. Argetoianu managed to plead for a release, using his personal connections with Ferdinand I, who reluctantly sided with Argetoianu. However, this event, known as the Averescu-Argetoianu split facilitated the splintering of the Democratic Nationalist Party as pro-Averescu politicians remained in the party, and pro-Argetoianu politicians in the party left and formed the Romanian National Guard with Argetoianu as their leader.

This unstable political situation allowed Bratianu and the National Liberals to bounce back, and the 1926 Romanian Elections was essentially a walkover for the National Liberals as they won a landslide victory over all of the other warring political parties, winning 70% of the national popular vote and controlling ~65% of the total seats in both the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate. But this landslide victory invoked a great deal of fear into some hot-headed members of the Romanian military, as the National Liberals were known for their pro-democratic socialist outlook. Fearing a (impossible) communist revolution, several members of the Romanian military led by Marshal Constantin Prezan rose up in defiance of the election results on the 19th of April, nearly a month after the elections and demanded the resignation of the new Bratianu government, which they deemed to be made up of socialists and syndicalists. Though Bratianu had appointed known socialists and syndicalists to his cabinet, the nuance laid in the fact that he had appointed democratic socialists and democratic syndicalists into cabinet, and Ferdinand I ordered the military to stand down. The Prezanists believed that the royal order that they received was a fake and continued to demand the resignation by gathering a large force of around 3000 troops outside of Bucharest. Ferdinand I responded by finally allowing Bratianu to approve military force against the attempted 19th of April 1926 Coup. A 5,000 strong brigade under the command of Marcel Olteanu crushed the Prezanists after the Battle of Berceni. Order was restored soon after and some modicum of political steadiness returned.

Prezan leading the attempted coup

Unfortunately for Romania, the events of 1915 – 1926 were only the foreshadowing of what was to come in the future.

Next Chapter: The Swedish Republic of Ostrobothnia (66)

Greece

Greece by the end of the first half of the 1920s was a changing nation. For sixteen years, Greece had been under the premiership of Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos, a man whose political acumen and leadership had carved himself a name in the history of Greek and Balkan politics. However, even as Venizelos’s successes remained great, his political opponents were moving against him as the 1926 Legislative Elections came forward. Venizelos had ruled uninterrupted for sixteen years and political fatigue became a huge problem for Venizelos as his opponents were gradually becoming more and more popular with the general population. The United Opposition had fallen apart after the 1922 Legislative Election failed to secure a victory, however as Panagis Tsaldaris retreated from the leadership of the People’s Party and allowed veteran politician Dimitrio Goundaris to retake power as leader of the party, the People’s Party had experienced a massive revival, and local municipal elections throughout Greece saw a large amount of politicians from the People’s Party take power. The endorsement of powerful leaders such as Xenophon Stratigos and Nikolaos Stratos to the People’s Party only added to the general popularity of the People’s Party. Other Anti-Venizelists, such as Ioannis Metaxas and Alexandros Paanastasiou continued to increase their own political influence and power as well.

Venizelos

The Greek Political Legend

But perhaps the greatest problem that of Italy. Italy under the collective leadership of Antonio Gramsci and his allies in the Italian Communist Parliament was starting to recover from its economic and military defeats in the First Great War and subsequent Italian Revolution. Gramsci was instead driving Italy forward with the focus on industrialization, procreation, and militarization leading to Italy having a much stronger position than it enjoyed half a decade earlier, and Gramsci was eager to build up Italian influence beyond its own borders through the means of economic investments. Gramsci first offered Greece economic investments in 1924 which Venizelos rejected, as he was still wary of the new regime in Rome, and the Greek Conservatives would have been furious if he accepted an investment offer from a communist nation instead. King George II was also hesitant of an economic relationship between Athens and Rome, and thus that killed any sort of ideas of Italian investments for the time being. But Gramsci was not deterred and soon, more and more tempting economic offers from Rome found themselves on the desk of the Greek Prime Minister and finally on the 12th of January, 1926, Venizelos was tempted beyond his limits and allowed 6 Italian factories to be opened up in Thessaly and Greek Epirus in return for a large 45% royalty sum to the Greek government, which was an extremely beneficial deal economically. Yet, it outraged the conservative People’s Party and even the left-wing Agricultural and Labour Party was wary of the idea and tepidly warned against it. War with Italy was a question that had burned hard in Greece since the early 1900s, ever since Italy’s Mediterranean Ambitions cropped up after 1902. The new Communist Regime in Italy had certainly inherited said dreams and many in Greece were fearful of war with Italy. Major General Nikolaos Trikoupis, the Military Commander of the Corfu Military District warned Athens that Greece had to prepare for eventual war with the Italians, which he deemed inevitable as the Communists continued to engage in intrigues in Greece.

Venizelos was also getting old by that point, and even his own son, Sofoklis Venizelos, was getting rather concerned about Greece’s preeminent Prime Minister who was suffering from more and more health problems as time rolled by. Finally, after suffering a stroke on the 29th of January, 1926, Venizelos decided that he would retire from politics and his occupation and gave up the position of Prime Minister of Greece to his capable Finance Minister, Georgios Kafantaris. Kafantaris became Prime Minister of Greece on the 31st of January, 1926 and he was more than capable of understanding the difficulties that Greece was about to face. Italy was a prime concern for the Greek Prime Minister, and furthermore, Serbia was also becoming a concern for the new government in Athens. Britain’s lukewarm attitude towards Greece after the Great War due to a successive amount of inward looking British Prime Ministers meant that Britain could no longer be trusted with securing the territorial integrity of the Kingdom of Greece, which was becoming warier and warier of Rome and Belgrade as successive economic and diplomatic dealings only furthered Athens’s apprehension. Kafantaris as such, turned to the Ottoman Empire to the east.

Georgios Kafantaris

Prime Minister of Greece (1926 - 1933)

The Ottoman Empire had stagnated from 1827 to 1908, despite the efforts of the Tanzimat to do otherwise, but the 1908 Revolution had been like a spark that had burned down the old and ushered in the new. Economically robust after the comprehensive Ahmet Riza reforms of the mid-1910s, and militarily secure after the Balkan War of 1915, the Ottoman Empire had proven itself both on the economic and military playing fields. Further, due to the 1911 Treaty of Salonika, Greece enjoyed a rather beneficial cooperative relation with the Ottoman government. The newly created Aegean Class Heavy Cruiser was made by Greece and the Ottomans in tandem with one another, already showing the capability to work together for defensive arrangements. Kafantaris, always a pragmatist at heart, was also looking favorably to the Ottomans due to the Anglo-Ottoman Alliance, which gave the government in London a duty to honor her alliance. With Britain ignoring Greece in favor of containing Russia for the time being, having a more formal allied treaty with the Ottomans was seen as a possible solution in Greece. On February 22, 1926, Kafantaris broke his idea of a formal Greco-Ottoman Alliance to secure Greece’s economic and military future to his new cabinet, which was met with mixed responses. Pragmatists were more than happy about the idea, as it gave Greece collective security beside the Ottomans, and as the economic clauses of the 1911 Treaty of Salonika were due to be terminated by the end of the month, renewing them would have been much easier if Athens and Constantinople were in formal alliance. However, old public sentiments died hard, and many were wary of an alliance with the ‘Old Enemy’ so to speak.

The idea soon broke into the Greek public. Crete and the Greek Peloponnese became the leaders of the anti-alliance faction in Greece, whilst Cyprus and Thessaly, both having significant Turkish and Muslim populations, became the leaders of the pro-alliance faction in Greece, whilst the other regions in Greece had their own differing ideas of such an alliance. As the new elections were called for in 1926 the idea of an alliance with the Ottoman Empire became the most heated issue in the political arena of Greece. The People’s Party led by Gounaris was vigorously opposed to the idea of an alliance with the Ottoman Empire, whilst the Agriculture and Labour Party remained neutral on the topic, instead seeking to further the rights of the common laborer and worker in the Greece rather than tackling the hot issue of an alliance. The Liberal Party instead was a pro-Alliance party, and campaigned in the promise of collective security. When it came right down to it, the Liberals and the People’s Party held an equal amount of votes, and the muslim voters of Greece became the deciders of the 1926 election in Greece. With the Muslim Greeks solidly in favor of an alliance with the Ottoman Empire, the vote turned in favor of the Liberal Party, and the Liberal Party managed to eke out a victory in the 1926 elections with a majority of 1 seat. The muslim population of Greece had become the deciding vote for the first time in Greek electoral history.

His policy vindicated through the election, Kafantaris began to prepare to lay the foundations of the infamous Greco-Ottoman Alliance.

Bulgaria

By 1924, Bulgaria had recovered. Prime Minister Nikola Mushanov, and the Bulgarian National Recovery Coalition Union had managed to fulfill its role pretty well. Bulgaria’s economic output reached pre-1915 levels for the first time in a decade, and new industrial zones and estates meant that manufacturing was growing. Relations between Sofia and Constantinople had turned cordial with one another and the power and influence of the military, once massive, had been scaled down after Ivan Valkov’s failed coup in 1918. But, as with any successful coalition, immediately after its goals of national recovery were completed, the coalition splintered apart. The Bulgarian Agrarian National Union wanted what was essentially a Crowned Republic, which even the Constitutional Democratic Party of Bulgaria, Mushanov’s party, deemed unacceptable, and the Social Demorats under Yanko Sakazov wanted a fully-fledged republic, which was opposed by both the BANU and the Democratic Party. Danev’s Progressive Liberal Party was the only party that remained firm in its belief that the Kingdom/Tsardom of Bulgaria was there to stay.

Bulgaria in the 1920s

The 1924 Bulgarian Parliamentary Elections became a heated affair as a result of the dissolution of the National Recovery Coalition, and the result was a hung parliament as the Progressive Liberals, Radical Democrats, BANU, Democrats and Social Democrats received a near equal amount of seats in the Bulgarian National Assembly as each party received a number of seats between 40 to 50 in a legislature which contained a total of 236 seats. Aleksander Stamboliyski, the leader of the BANU took advantage of the political confusion and tried to form a coalition with the Social Democrats, which fell through due to the unrepentant republican position of the Social Democrats, whilst the attempts of Mushanov to form a coalition with the Progressive Liberals and Radical Democrats fell through due to the fact that all of these political parties did not trust the other. This became known as the 1924 Bulgarian Parliamentary Crisis. With no government in power, and all of the political parties unable to work with one another, Bulgaria was effectively running without a government in 1924, and this forced King Boris III to take action.

Boris III had watched the rather weak and unstable National Recovery Coalition and the subsequent political moves with growing irritation and using the Tarnovo Constituion of 1879, dissolved the Bulgarian National Assembly on December 2, 1924 and then took near-absolute control of Bulgaria through royal decree and Articles 61 and 62 of the Tarnovo Constitution which gave the Bulgarian Tsar near absolutist powers in the case of political crisis in the Bulgarian nation. Boris III then turned and solved the political crisis in Bulgaria in the most surprising manner possible. He decreed that every political party was from December 15, 1924 onwards banned, and instead introduced a new system of non-partisan parliamentary democracy. Mushanov’s position as Prime Minister was then removed and Mushanov, caught off guard by the wily king’s virtual coup de etat, resigned from politics, and the position of Prime Minister of Bulgaria was then offered to General Vladimir Vlazov, one of the few successful Bulgarian generals of the Balkan War and a firm royalist. He was also the Mayor of Sofia from 1919 to 1923, in which role he successfully modernized the capital of Bulgaria. Vazov accepted the offer and became the next Prime Minister of Bulgaria, ending the 1924 Bulgarian Parliamentary Crisis.

Boris III was essentially trying to create a new regime of democratic, yet royalist (with significant powers to the monarch) ideals. This proved to be a hard thing to conduct. Vazov had proven himself to be a capable administrator during his time as the Mayor of Sofia, and this showed through his immediate actions upon taking the office as Prime Minister. He approved several new land laws, and the economic and commercial requests that were pending due to the governmental crisis were immediately looked after by Vlazov’s new cabinet, which itself was appointed quickly to avoid further delays in governmental capability. Vazov’s appointment had been a smart choice, but the two powerful personalities were not sure how to create their shared vision of a democratic yet royalist regime in Bulgaria. While no formal idea was produced, this vision eventually led to what became known as the ‘Boris-Vlazov’ system. This system was in essentiality, a puppet cabinet and a puppet government whenever Boris III wanted something done, yet a democratic and accountable government when Boris III decided not to interfere personally. And the first time this was used was in early 1925, when Vlazov made it clear to Boris III that he wanted to remove the influence of the Bulgarian military in politics, which still lingered, despite the attempted coup of 1918. Boris III was in favor of this policy whole heartedly and both men were blessed with good fortune in this endeavor.

Boris III appointing the new Royalist Regime in Bulgaria.

This was the Starting of Borisian Bulgaria (1924 - 1968)

Damyan Velchev was driven into exile due to his links with the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO). The IMRO, which had once been a tool of the Bulgarian government for irredentist desires had become their own enemies after the Bulgarian government failed to conquer Ottoman Slavic territories in 1915. Velchev’s influence in the army was massive, and his desire to be involved in Bulgarian politics was what partially drove the Bulgarian military to interfere with the country’s politics. HE was arrested on orders of the King, and though Vlazov was eager for the death sentence, that was commuted to life imprisonment by Boris III. Kimon Georgiev, another active military officer who was known to meddle in Bulgarian politics was removed from his post and sent into de-facto exile by becoming the Military Attaché of Bulgaria in Vienna. Velchev and Georgiev’s political military organization, the Military League was abolished, and a subsequent purge in the Bulgarian military flushed out most members of the Military League from the Bulgarian Army. This swift action by Vlazov and Boris III basically culled all the influence the army had on politics in Bulgaria, thus essentially making the army a non-existent factor in Bulgarian politics for the time being.

Boris III and Vlazov became more and more popular among the Bulgarian population as time went by, despite the misgivings of the general populace towards the new pro-royalist government and non-partisan regime. Boris III continued Mushanov’s policy of rapprochement with the Ottoman Empire, and the Kingdom of Greece, which saw Ottoman aristocrats being able to buy estates and invest into the Bulgarian industrial economy for the first time since 1881. It also saw the marriage of King Boris III with Prince Olga of Greece. Since 1922, during a small visit to Greece, Boris III’s attention had been caught by the daughter of Prince Nicholas of Greece and Grand Duchess Elena Vladimirovna of Russia. Considered to be one of the most beautiful princesses of the time, Princess Olga was initially indifferent to Boris III’s attempts to court her, partially due to her misgivings regarding the fact that Boris III was nearly a decade older than her. However, Boris III’s charm and charisma eventually broke through her cold exterior and the two announced their engagement in early 1924. In a ceremony partially intended to shore up support from the populace to Boris III’s new regime, a public royal wedding took place in Sofia on January 27, 1925, which saw Princess Olga of Greece become Queen Olga of Bulgaria. The marriage became a successful event, as the Bulgarian people adored their new pretty Queen. Her Bulgarian, which she spoke with a heavy Greek accent was considered humorous, and her calm exterior only served to attract more people towards her. Boris III also remained amenable and most of the public soon came to like their previously detached King. He started to drive his car through the country with no special guards around him, and often stopped to converse with the general public. During these driving sessions, he gave lifts to pedestrians in Sofia and gave several small gifts to the people he came across during these sessions. This ‘driving’ session made Boris III and his royal regime in Bulgaria much more popular than ever before.

Queen Olga of Bulgaria

Princess of Greece

Whilst Boris III took care of public matters with his new wife, Vazov got around healing the political and economic wounds of Bulgaria. The disastrous Civil War and Balkan War had led to a few years of negative population growth, and in order to combat that, the Bulgarian Prime Minister introduced several pro-natal policies by giving maternity leaves and breaks to women, and giving several tax breaks for families with pregnant women. This allowed Bulgaria, which had been registering barebone growth rates of ~0.2% since 1916 to grow towards ~1% as the result of Vlazov’s policies. The agricultural backwardness of Bulgaria, which still relied on pre-1900 equipment was addressed by the procurement of modern agricultural tools from Britain, America and the Ottoman Empire. Commercialized farming was encouraged through higher interest rates in loaned or rented out lands, and extra revenue was used in the construction and establishment of various new industrial estates, giving the Bulgarian people the much-needed employment that they desired. Adopting a paternal attitude, labour reform was passed by Vazov’s regime was well, monitoring the health and capabilities of workers in the Kingdom.

Prime Minister Vladimir Vasov of Bulgaria (1926-1938)

And though Boris III and Vlazov didn’t know it, they were laying the foundations of the Bulgarian Resistance against the Berlin Concorde during the Second Great War. Bulgaria’s resistance was crucial in the victory of the Ottoman Empire in the Balkan Front. Boris III’s royal regime survived the test of lasting more than a single year, and by 1926 the new non-partisan government chugged on, intent on modernizing the country and becoming the ideal ‘modern kingdom’.

Romania

The Romanian gains in the Balkan War had been rather small, with Romania only gaining south Dobruja from the Bulgarians, even though the Romanian territorial gains were higher in comparison to the Ottomans, who annexed a few border forts and nothing much else. Economically, Romania gained much more. The Bulgarian war reparations had basically nullified Romania’s own debt, and the freeing and demilitarization of the Bulgarian side of the Danube River had led to a significant economic boom in the region, much to the pleasure of the Romanian government. Romanian Prime Minister, Ion Bratianu, and his political party, the National Liberal Party seemed unassailable after the victory in 1915. Romania’s continued occupation of parts of northern Bulgaria until 1918 also saw Romania gain what was in their own eyes, military prestige. In spite of these victories, the failure of Romania to intervene in the Great War on either one side was seen as treasonous. Romania had been the nation to gain the most from the War, with Besserabia and Transylvania up for grabs, but the warring political factions in Romania at the time, the Conservative Party, Conservative-Democratic Party, and Democratic Nationalist Party had all been unable to reach a consensus regarding the war and had missed their chance to jump on the Great War bandwagon after Austria-Hungary left the war. There was no way Romania was going to take on Russia by itself, and the entire question and debate collapsed onto itself after Austria left the Great War.

Ethnic Map of Dobruja

Romanian nationalists had been hoping to gain either Besserabia or Transylvania, and when it was apparent that neither of them were going to be attained due to the bull headedness of the Conservative and Conservative-Democratic Party, Romanian Nationalists began to vote for the Democratic Nationalist Party, the party which had been most in favor of war during the Great War. The National Liberal Party barely managed to win the 1918 General Elections. Bratianu hoped to reinvigorate the National Liberal Party by involving itself more into social and economic matters but that idea remained unsuccessful as the Romanians were unwilling to focus entirely on the economy and social affairs. This was a bad move. Pre-1915, only 8% of Romania’s population identified as non-Romanian, but with the acquisition of South Dobruja, 15% of Romania now identified as non-Romanian, and this substantially increased minority soon became vocal in their efforts with either secession or with political representation. The Roma People, under the self-declared Gheorghe Niculescu, allied with the Ukrainian leader, Emil Bodnaras and his party, the Slavic Representation League, to demand more political and social representation and freedoms for the two minorities. Turks and Tatars in Romania also allied with Bodnaras and Niculescu, asking for greater autonomies. This alliance between the Roma, Slavs and Turks in Romania became known as the Romanian Minority Representation Association (RMRA), and the RMRA soon became a major headache for the Romanian government in Bucharest. Bulgarians from North Dobruja became involved in representation politics, whilst Bulgarians from South Dobruja became involved in secessionist affairs. And even though the regionalist and secessionist Bulgarians in Romania did not agree on the topic of regionalism or secession, they coordinated with one another politically to keep up the political pressure.

King Ferdinand I of Romania became more and more irritated with the growing political disaffection in Romania and asked (demanded) that Bratianu find a solution to the crisis. To be completely fair to Bratianu, he did create the Romanian Roma Council, a representational commission for the Romani people, and also allowed Bulgarian majority counties to be bilingual in both governmental and educational affairs, thereby diffusing ethnic tensions between the two minorities. Turks and Tatars gained an allocated amount of seats in the Romanian Chamber of Deputies (8) and Senate (3) which allowed tensions between the largest minority of the country and ethnic Romanians to die down as well. But where the ethnic minorities had started to mount political pressure on the government, the Democratic Nationalist Party picked it up and continued to create more instances of political problems in Romania. The National Liberal Party, as expected failed to gain majority in the 1922 elections and paved the way for the Democratic Nationalist Party under the leadership of Alexandru Cuza.

Cuza’s premiership was controversial. Though a social democrat in terms of economic affairs, he was a far-right politician in matters such as social lifestyle, and ethnic politics. He was also, a hard anti-semite. Being a Jew in Romania became extremely hard under his premiership, as new restraints and restrictions were imposed on the Jewish community of the nation, much to the vexation of King Ferdinand I. Cuza rejected Jews from public life, and intended to have them held up in private through internal means, diverting their needs and wants to other things. This led to much annoyance in the Romanian Jewish population and the more outraged Jewish families simply bought immigration tickets and immigrated to Austria/Danubia, Bulgaria or the Ottoman Empire, all of which were far more pro-Jewish states. Cuza, also an avowed prohibitionist passed several dry laws that made millions of Romanians to become criminals overnight (even though very few of them {a couple hundred} were ever prosecuted for breaking the dry laws). But his most controversial policy was the creation of the Jewish Quota Bill in 1923 that intended to keep a Jewish quota on everything, such as education, banking, land ownership etc. It was the last straw and pro-semites throughout Romania took the striking against the bill. Even many members of the Democratic Nationalist Party came out against the idea of the Jewish Quota, yet Cuza remained stubborn and was unwilling to negotiate or compromise. This saw King Ferdinand I dismiss Cuza from the premiership and appointed Alexandru Averescu, a more moderate member of the Democratic Nationalist Party, as the new Prime Minister of Romania.

Romania in the 1920s

Averescu was a reactionary and far-right politician himself (though he was neutral on the Jewish Question unlike his far-right colleagues), but what set the man apart from his colleagues was that the man was cunning, devious and pragmatic. A dangerous combination in politician. Averescu’s first move was to remove the Jewish Quota Bill and he also reversed the Jewish restrictions and limitations introduced by Cuza. A prohibitionist himself, he did not remove the dry laws, but he did remove the more severe penalties of breaking them. Averescu’s next line of policy was seen when he cracked down on the various communist and left-wing groups operating in Romania. Born out of his fear of the Italian Revolution and the Italian Communists, Averescu banned several left-wing parties, only allowing center-left political parties to remain legal in the country. Averescu was willing to stop there, but the more zealous members of his cabinet, such as Constantin Argetoianu, went further and conducted several arrests of left-wing politicians. Averescu and his close allies in cabinet were not even informed of the arrests taking place until Averescu noticed that several previous members of the Chamber of Deputies and Senate were missing when he proposed a new economic stimulus bill in 1924. It was basically fait accompli on part of Argetoianu’s part, but Averescu was furious and had Argetoianu himself arrested and thrown into prison. Argetoianu managed to plead for a release, using his personal connections with Ferdinand I, who reluctantly sided with Argetoianu. However, this event, known as the Averescu-Argetoianu split facilitated the splintering of the Democratic Nationalist Party as pro-Averescu politicians remained in the party, and pro-Argetoianu politicians in the party left and formed the Romanian National Guard with Argetoianu as their leader.

This unstable political situation allowed Bratianu and the National Liberals to bounce back, and the 1926 Romanian Elections was essentially a walkover for the National Liberals as they won a landslide victory over all of the other warring political parties, winning 70% of the national popular vote and controlling ~65% of the total seats in both the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate. But this landslide victory invoked a great deal of fear into some hot-headed members of the Romanian military, as the National Liberals were known for their pro-democratic socialist outlook. Fearing a (impossible) communist revolution, several members of the Romanian military led by Marshal Constantin Prezan rose up in defiance of the election results on the 19th of April, nearly a month after the elections and demanded the resignation of the new Bratianu government, which they deemed to be made up of socialists and syndicalists. Though Bratianu had appointed known socialists and syndicalists to his cabinet, the nuance laid in the fact that he had appointed democratic socialists and democratic syndicalists into cabinet, and Ferdinand I ordered the military to stand down. The Prezanists believed that the royal order that they received was a fake and continued to demand the resignation by gathering a large force of around 3000 troops outside of Bucharest. Ferdinand I responded by finally allowing Bratianu to approve military force against the attempted 19th of April 1926 Coup. A 5,000 strong brigade under the command of Marcel Olteanu crushed the Prezanists after the Battle of Berceni. Order was restored soon after and some modicum of political steadiness returned.

Prezan leading the attempted coup

Unfortunately for Romania, the events of 1915 – 1926 were only the foreshadowing of what was to come in the future.

Next Chapter: The Swedish Republic of Ostrobothnia (66)

I wonder how Germany would be doing… not so well, fully subscribing to the stab in the back theory by Austrians and possibly Bavarians…Next chapter will be on Central Europe.

Like Weimar, the temporary prosperity and recovery has soothened attitudes, but that's only going to be temporary......I wonder how Germany would be doing… not so well, fully subscribing to the stab in the back theory by Austrians and possibly Bavarians…

Merry Christmas!Good update. Merry Christmas, BTW (or whatever your holiday is)...

This TL Balkans seems more brighter than OTL but the tragedies and dramas of conflicts will still remains. The Balkans is always messy, geopolitically.

Anyway, Merry Christmas!

Anyway, Merry Christmas!

Like a wise man once said - "The Balkans will remain as the Balkans!". So yeah, true.This TL Balkans seems more brighter than OTL but the tragedies and dramas of conflicts will still remains. The Balkans is always messy, geopolitically.

Merry Christmas!Anyway, Merry Christmas!

pretty much yeah1. So... the Balkans are somewhat doing better but still being the Balkans...

we will see!!2. I'm still not enthusiastic about 'The Swedish Republic of Ostrobothnia' especially for the non-Swedish speaking Finns...

Merry Christmas!That's about it, Merry Christmas and Happy New Years!!

Never let any monarchy be restoredgreat CHAPTER

I am glad that the Ottomans defeated the Zaidi rebellion. Now my country, Yemen, will be able to develop well

It seems that with the Baltic crisis, the empire will become an honest and impartial mediator

Portugal supports the restoration of the Brazilian monarchy??? I think France will (the Orleans inherited the Brazilian throne claim after Pedro II's death)

Let's hope the monarchy is restored

I'm sorry but I do not like state-funded authoritarian waifusAny monarchy must be restored

Who only get away with anything because divine right of kings

I'm sorry but I do not like state-funded authoritarian waifus

Who only get away with anything because divine right of kings

Monarchies need not be autocratic

Threadmarks

View all 110 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Holidays in the Ottoman Empire Chapter 66: The Swedish Republic of Ostrobothnia & Growing Disillusionment Look into the future [4] Chapter 67: cultural update – The Top 3 Sports in the Ottoman Empire turtledoves 1926 Ottoman General Elections Map. Chapter 68: African Rumblings. Chapter 69: Land of the Unfree

Share: