Im really confused where italy stands here now in the conflict. Also how will french and ottoman relations work frenemies or will they go against each other post war.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Osman Reborn; The Survival of Ottoman Democracy [An Ottoman TL set in the 1900s]

- Thread starter Sarthak

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 110 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Holidays in the Ottoman Empire Chapter 66: The Swedish Republic of Ostrobothnia & Growing Disillusionment Look into the future [4] Chapter 67: cultural update – The Top 3 Sports in the Ottoman Empire turtledoves 1926 Ottoman General Elections Map. Chapter 68: African Rumblings. Chapter 69: Land of the Unfreea zog moment, if you willI believe in the twitch community, this would qualify as a "pog" moment.

Love the pop-cultural part of this TL. It’s a nice way to elaborate more on people’s lives and what’s like to be in the world.1944, Athens, Kingdom of Greece

Alexandros Papagos muttered curses underneath his breath as he looked at the map of the trenches outside of the city of Athens again. The Germans and Hungarians were pushing deep into the final lines and if the last lines fell, then despite the turn of war, Athens would fall, which would be devastating to the cause of war for the Allied Powers. He stumbled down onto his chair rubbing his eyes, not knowing what to tell the King and Prime Minister in his daily report. He picked up the pen and a sheet of paper before sighing and stowing them away again. He was about to stand up and take a glass of much-needed wine when a message courier stumbled into the office.

Papagos simply raised an eyebrow in question. Instances such as these had happened too many times during the siege for him to be angry about it anymore.

"General." The courier gasped. "The Ottomans.......The Ottoman 5th Army has arrived in Avlona sir. They have defeated, with British air support, a German counterattack. The Germans are now surrounded on the Attican Peninsula."

The dread of defeat was immediately replaced by the vigor of victory. Papagos stood up immediately and dismissed the courier and started his report quickly. Who knew that 500 years after the Ottomans came to Athens to conquer it, they were once again coming to Athens.......only this time to liberate it.

1943, South China Sea

Chen Shaokuan, Captain of the Qianlong Cruiser didn't know what to expect. The British had warned him that after years of deflecting the issue, the government in Constantinople had finally agreed to send a small detachment of ships from the Red Sea Fleet and Persian Gulf Fleet to aid the Sino-British Naval force against the impending Japanese Naval attack. Commanding the 3rd Cruiser Squadron, Chen was anxious to finally destroy Japanese Naval Superiority in the South China Sea, and to finally isolate the Japanese troops in Indochina as a result. The War in Manchuria was going badly and the Chinese government needed this reprieve now more than ever.

As the morning mist dissipated, he could see the Ottoman squadrons - two squadrons had been sent apparently - arrive next to his own squadron. Whilst most of the ships were medium and small in scale, destroyers and light cruisers, an imposing battlecruiser, the only battleship the Ottomans had sent apparently, led the Ottoman Squadrons, and flew the banner of the Ottoman Kapudan Pasha, signifying its role as flagship. Chen had heard about this particular battlecruiser. Built by Franco-British contractors in Constantinople in 1935, and only commissioned in late 1940. The Hayreddin Barbarossa. This ship and its class were apparently the answer of the Ottomans against the Italian Augustus Class. It's large guns and armor gleamed in the morning sun as the Sino-Ottoman squadrons neared each other.

Chen finally stood up and straightened to enter the allied ship for battle planning. The small amount of ships sent by Constantinople - damn the politicians and bureaucrats for that! - meant that the Ottoman ships would not be able to play a large role in the Battle that was to come; but they would still be crucial, Chen knew that for sure.

January, 1944, Occupied Albania

For Ahmet Muhtar Zogoli, time flew by in the small camp of his militia like an immediate blink. The daily routine was the same. Wake up, eat breakfast, go and disrupt Concordat supply lines, and then retreat, come back to camp, eat dinner, and sleep. It had been three years already, Zogoli mused. But for now, he had another important mission to conduct; that of weapon's procurement.

The government in Constantinople had enforced strict gun regulations after the troubles in Yemen in the late 1920s and early 1930s, and as a result, finding actual guns in the Ottoman Empire not commissioned by the government, occupied or not, was a tiresome job. But for now, the Ottomans, supported by British and French airpower were ferrying much-needed weapons to guerilla leaders like him through transport ships. He gripped the pistol in his right hand whilst following the map in his left hand. One eye of his focused on the map and another on his surroundings. After a few minutes of tense walking, he saw a few crates scattered in a small clearing inside the dense Albanian forests of Peshk. He allowed himself to grin slightly and whistled. A few seconds later, his men appeared behind him, and soon the crates were being transported to his camp.

As Zogoli turned to leave, his mission completed, he saw the air trail of planes in the sky. In the distance, a blurry form of Ottoman and British transport ships flew away. Zogoli smiled and saluted the disappearing planes before disappearing into the woods as well.

Chapter 54: The Birth of Radicalism

Chapter 54: The Birth of Radicalism

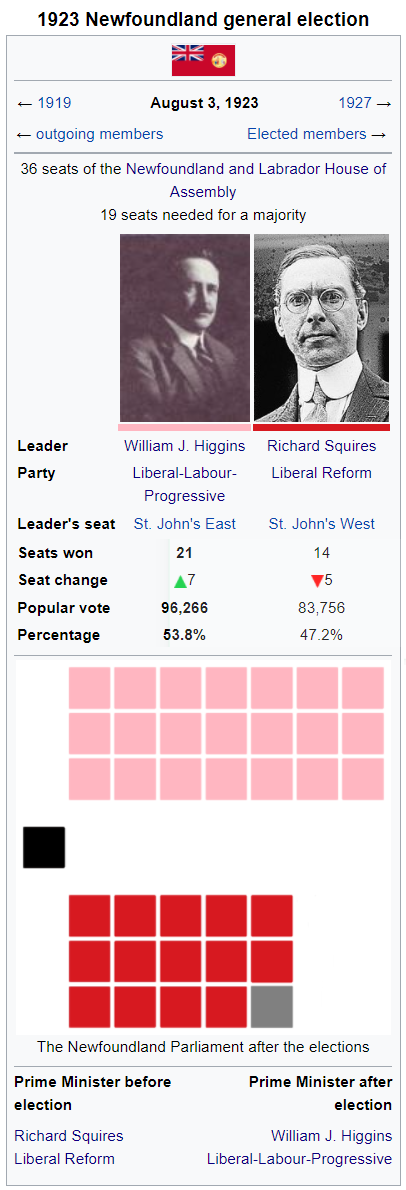

“Until acquiring Dominion Status in 1907, Newfoundland and Labrador were mere colonies in the British Empire. One that was filled to the brim with white settlers yes, but just another colony. But the achievement of dominionship in Newfoundland opened up the colony to a whole new myriad of dominion style politics. Under Sir Robert Bond, the Newfoundland Dominion reached the pinnacle of its economic growth. Railroads were constructed, a mix of liberal free trading and protectionist policies made the fisheries that the island nation was so dependent on grow to a whole new height. However, his rather large disposition towards free trade hurt the rights of the Fishermen in Newfoundland, and he was defeated in 1909. He was succeeded by William Coaker, and then Coaker himself was succeeded by Edward Morris, a Catholic from the pro-Catholic People’s Party of Newfoundland.

When the Great War broke out in 1915 its cause was met with near unanimity within Newfoundland. Recruiting was fast, and a general feeling for ‘King and Country’ did reign supreme within the new dominion, and around ~7,000 men volunteered for the Newfoundland Army within a month, and another 2000 men joining the Newfoundland Navy. Around 4000 other Newfoundlanders joined the British war effort through the Canadian or British forces as well. For a country of just ~250,000 people, a manpower pool of ~15,000 men joining the war effort was a legendary undertaking in simply fact of numbers.

However, whilst the war was popular early on, and to an extent, remained popular, the governing government had fallen with accusations of wartime corruption and giving more fishing rights to the Canadians. The Royal Governor, Sir Walter Davidson did try and make the issue resolved, but his establishment of the Newfoundland Patriotic Union as a non-partisan base of debate only made sure that political tensions in the Dominion rose. As a result, in early 1917, an all-Party National Government was formed. Unlike Canada, the country did not get into a major conscription crisis, however, it did force the Fisherman’s Party to dissolve into history, as a schism arose within the party as its leaders supported conscription whilst its members opposed conscription.

Newfoundland troops during the Great War

During the Great War, the Newfoundland Regiments in service of the British Empire performed admirably. They were mostly deployed to the African Front, where they played a key role in the defeat of German East Africa and German Kamerun. 2 Regiments also fought in the Western Front Alongside British and French forces. In particular, the small Battle of Charleroi, which happened during the Second Battle of Waterloo as a sub-battle saw 1200 Newfoundland soldiers defend the small Belgian village against a German assault seven times before giving ground. In Newfoundland, the Battle was seen as a romantic battle, a last stand of the Newfoundlanders if you will, and like Canada and Australia, the Dominion of Newfoundland felt an upswing of nationalism towards their own countries.

The remnants of the fisherman’s union joined with the Liberal Party of Newfoundland to form the Liberal Reform Party of Newfoundland, led by one Richard Squires, who won the 1919 General Elections rather handily. Squires was and remains a controversial figure in Newfoundland History. His early reforms did expand education for all within the Dominion, and his development of the Humber River in Newfoundland led to some amount of economic growth that saw the growth of the fisheries. However, these reforms also led to a price collapse of the northern fisheries, which made the man extremely unpopular in the majority of the electorate after 1921. The growing anti-Communist surge in the Dominion also targeted Squires when he nationalized the railway networks on the island in 1922. Italian-Newfoundlanders, already having a small community in the island were virtually thrown out due to anti-communist paranoia, and such a nationalization scheme only made Squires more distrusted and more hated among the general population.

Richard Squires

When in 1923, when new elections were called for August of the year, the Newfoundland People’s Party, or the Liberal-Labour-Progressive Party as they were called in an official capacity, had rebounded from their fall to power in 1917. Largely due to the efforts of one man and his supporters – William J. Higgins. Working as a clerk for a time in the party, he had joined the Royal Navy during the Great War and had distinguished himself during the Battle of Devil’s Hole, winning several military award along the way. After a general ceases in hostilities he returned to Newfoundland and was elected the Speaker of the Newfoundland Assembly in 1918. In 1919, he was elected the leader of the People’s Party after the failure of the party to win the 1919 elections. A man learned in the ways of law and justice through a degree he had earned, and a man with a military record, he drew massive support from the legalistic and veteran populace of the Dominion. Furthermore, his party’s pro-Catholic position meant that the support of the Catholics – mainly the Irish Newfoundlanders and the Scottish Highlanders of Newfoundland – was also assured.

William J. Higgins

That was not enough to win an election with a landslide, but luck was in favor of Higgins. Just one month before the elections, Squires was hit with a massive barrage of corruption allegations. None of them were ever proved, but the allegation of accepting bribes and giving nationalized business’s to the highest bidder hurt the reputation of Squire greatly, and even the most radical anti-communist started to look at the People’s Party, a Social Democratic Party, with some speculative gaze. The elections were not polarized in the sense of polarized politics like the one going on in America, or even other polarized nation-states, but it was filled with tensions, that was for sure.

Higgins’s People’s Party managed to come out on top, and won 21 of the 36 seats in the Newfoundlander Parliament, winning an absolute working majority. The greatest problems now facing Higgins as Prime Minister of Newfoundland were the two hot-button issues of Full Women’s Suffrage and the Labrador Border Dispute with Canada. Squires had implemented a partial women’s suffrage scheme in 1921, and around 92% of the women that were given the right to vote did do so in 1923. The rest of the women community were now agitating for full suffrage. This time, the Newfoundlander Suffrage Community drew inspiration from the United Kingdom, the Empire of Danubia and the Ottoman Empire. The Ottomans and the British had given women the right to vote already and the Danubians were well on track to give all their women the vote by the 1924 Legislative Elections. Though the orientalist annotations did offend many Ottoman citizens, the slogan ‘If the Turk Can Vote, why can’t we?’ became a popular slogan among the suffrage movement.

Higgins responded by creating the Suffrage Committee within the Parliament. The Committee filed a draft on the 28th of October, 1923 declaring that a full suffrage would be achievable by the next year, and that by and itself ended the issue of suffrage for women in the island.

The second and more pressing issue was that of Labrador. Labrador had been a long-standing dispute between Quebec and Newfoundland ever since 1867 when the Canadian Confederation was created. The Quebec Boundary Extension Act of 1912 which included Ungava into Quebec created a very loose border between Labrador and Newfoundland, sparking the dispute, as the two sides started to create overlapping claims against one another. Newfoundland asked the Canadian government for mediation between the Province of Quebec and Newfoundland in 1922 under Squires, however Quebec’s Premier, Louis-Alexandre Taschereau was opposed to this move, and instead moved the decision to the British Privy Council, making this regional headache a headache for London as well.

Reginald McKenna, the British Prime Minister directed the Privy Council to make a fast and sound decision ‘that would not alienate’ either Ottawa or St. John. Canada argued in front of the Privy Council that Newfoundland had only received a strip of land extending 1.6 kilometers from the coastline so that it could control the fisheries of the region, and that the rest of Labrador was a part of Quebec, and therefore a part of Canada. Newfoundland instead argued that the term coast which was used in communications between different officials throughout the Empire in regards to the Dominion of Newfoundland showed that a larger portion of the territory was meant rather than just a coastal strip. In order to make sure that the British were not implicated in an unpopular decision, the government made sure that the key decision judges of the Privy Council were Australians, New Zealander, and South Africans. And in the end, the Council deemed on the 18th of November, 1923 that the Labrador Dispute was in favor of Newfoundland because even the 1912 Quebec Extension Act had a small clause denoting that the land was rightfully Newfoundlander. This clause had been inserted by the Quebecois government in 1912 to make sure that there was no flare-up of tensions, but in the end, it had worked against them and their interests. Taschereau was livid, but he could do nothing much and had to accede, though he did withdraw his support of Prime Minister MacKenzie King, whom he viewed to have done little to back up Canadian/Quebecois claims. This led to a small political crisis within the Liberal Party, which saw King’s government fall during the Labrador Dispute. King was moved against with a motion of no confidence, and a dark horse candidate within the Liberal Party, Hewitt Bostock became Prime Minister of Canada, surprising many, as many thought that the more prominent candidates such as Charles Stewart or Ernest Lapointe would become Prime Minister. A more moderate candidate, Bostock however proved to be the least disuniting figure to rally around leading him to become Prime Minister.” Newfoundland and Canada in the Interwar Era: A History of Tumultuous Relations

“Ottoman Mesopotamia or Iraq, depending upon the person and record, entering into 1923 was a changing place. Having been a part of the Ottoman Empire since the 1630s, the area had many a historical links to other powers in the region, like Iran and the Arab Interior. However aside from the rebellion of the Iraqi Beys in the early 1800s, Iraq had remained a generally peaceful region in the Ottoman Empire. This relative peace in the region did allow for greater concentration of wealth and coming into the 1908 Revolution, Iraq was one of the richer areas of the Empire, with Baghdad being almost as grand as Constantinople itself, though with its own unique charm, and obviously less populated.

The ascension of Suleiman Nazif Pasha as the Governor of Baghdad in 1916 had transformed the Baghdad Vilayet into an administratively competent regime as well. Though Suleiman Nazif hadn’t been particularly good at any sort of administrative affairs before during his stay as Governor of Basra, Syria and the Archipelago Vilayet, he had learned from his mistakes, and by the time he took power in Baghdad, he had become a competent administrator in his own right. Furthermore, he was an avid writer, and having mastered Arab, Persian and French together with his native Anatolian Turkish, he was a highly learned man.

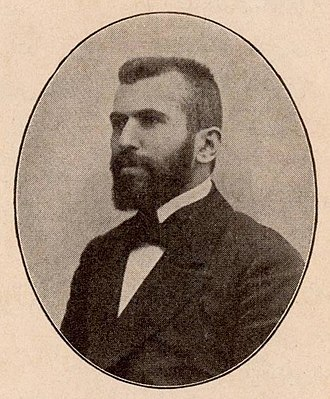

Suleiman Nazif Pasha

Nazif Pasha was a man who encouraged self-sufficiency and he wanted to make the best of the current economic miracle going on in the Ottoman Empire. He was also highly critical of the Liberal Union’s ruling government (he was a member of the CUP party) for allowing extra rights to the British for their oil exploration within the Baghdad Vilayet. Though obviously not sanctioned by either London or Paris, British and French oil hunters within the Ottoman Empire had a notorious reputation as being highly disrespectful to the Muslim population of the Empire. Further than just behavioral problems, Nazif Pasha attacked the belief that a deal with the west was required for oil exploration in the empire. He was firmly in the camp with the belief that allowing concessions to London and Paris regarding oil would come back to bite the Ottomans later.

When a small French company was arrested in Baghdad for harassing a small caravan of Bedouins, the French company demanded to speak with the Governor, demanding their release. In this event the Governor simply said no and did not even deign to meet the company, instead ordering them to go through the legal requirements. He became famous for his anti-European rhetoric at the time.

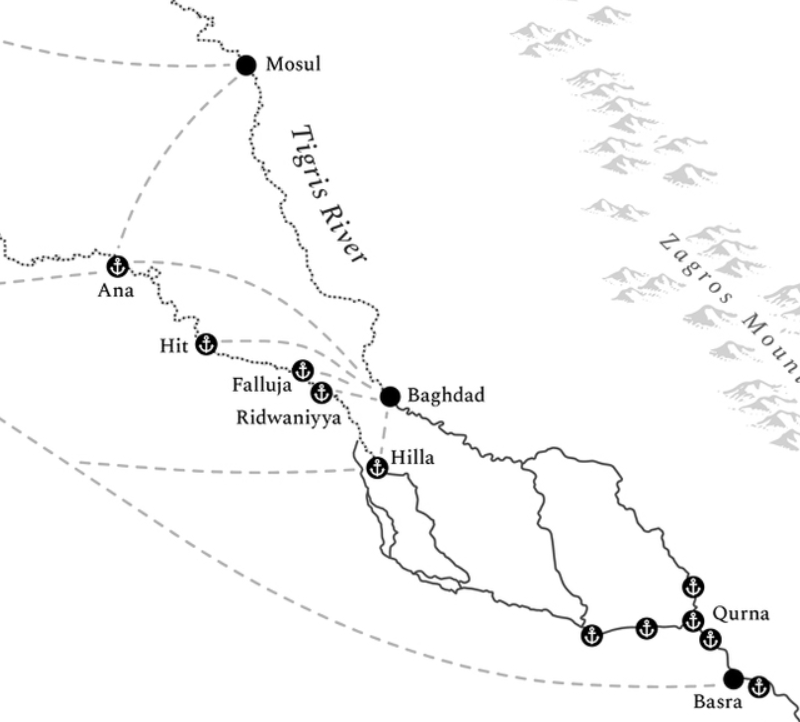

Furthermore, Ottoman Iraq remained economically lucrative. For the Ottoman Empire, Baghdad was what Palmyra was to the Roman Empire, as a vital link between Ottoman Anatolia and the Persian Gulf. Under Ahmet Riza, Ottoman Iraq had undergone a new revitalization of the Euphrates and Tigris Trade Routes. Latakia and Tripoli were once again connected to the Persian Gulf through Aleppo and Birecik, increasing intranational trade, and river ports were constructed in Ana, Mosul, Hit, Baghdad, Falluja, Ridwanniya, Hilla, Qurna, all the way to Basra, where a major port had been built under the command of Ali Kemal in 1913. This interconnectedness of river ports all the way to Basra facilitated a major growth in economic activity throughout the region, and became one of the key players of the Ottoman economic surge in the region.

Ottoman Riverports in Ottoman Iraq

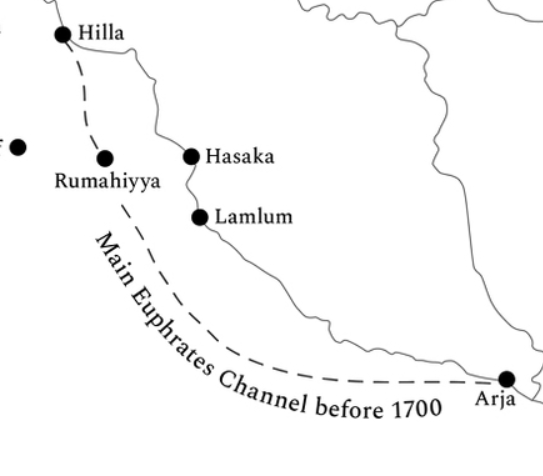

Riza had also been instrumental in the reconstruction of the Main Euphrates Channel, which allowed for more direct trade between Arja and Rumahiyya, and allowing for greater economic mobility in the region as a result. Drought, and the shifting river had made the canal invalid in the early 1700s and it was abandoned. But with advanced canal building and construction techniques of the early twentieth century, reopening the canal became possible and was pursued by the Ottoman government full steam ahead.

The Euphrates Canal

The Ottoman Agricultural Revolution spread into Iraq as well. The Marshes and Wetlands that surrounded the two great rivers of Mesopotamia were perfect for extra irrigation to supply greater number of farms, and was used as such. Farming production increased by 76% between 1915 and 1920 within Ottoman Iraq, signaling an extreme rise in agricultural potential in the region. The growing urbanization of the 3 Iraqi Vilayets also meant that more and more tracts of land became available for agricultural use as many villagers or nomads sold the lands they owned in the periphery and then used said money to immigrate to the three great cities of Baghdad, Mosul and Basra within Ottoman Iraq.

Coupled with all of these new economic factors, the Ottomans also experienced a massive shipping boom in Iraq. Coupled with the growth of internal river ports once more, the completion of the Basra International Port meant that the shipping lanes in the Persian Gulf became of utmost importance to the Ottoman Economy again, and money funneled down into the region from Constantinople. Shipping business’s cropped up throughout Basra and the River Ports, and civilian ship companies began to sniff for profit in the region. Ferries from Basra to Muscat and Bombay became regular as the city exploded in size and wealth due to the explosion of shipping throughout the region. This facilitation of water transport also led competition between the shipping industry and the railway industries. The Railways of Iraq were almost all concentrated near the Euphrates and Tigris, and at times, simply travelling by ship was more cheap or faster in comparison to trains. The railway companies responded by receiving a grant from Constantinople to build a cross desert railway path all the way to Damascus, making time for travelers from Basra to Syria cut almost by half. The Shipping companies responded by constructing faster transport ships for the rivers. This sense of competition greatly benefitted Ottoman Iraq’s economy, as competition gave way to innovation, and innovation gave way to increased wealth.

But underneath all of these developments, most of which were good, a more sinister development was taking place. The Ottoman involvement in putting down the Arabistan Crisis in Iran managed to make many of the Shia Arabs living on the Ottoman-Iranian Border feel threatened, and the small tribal beys and amirs of the Iraqi tribes, feeling their power threatened, began to advocate for a complete separation of Iraq from the Ottoman Empire, in line with Arab Nationalism. Arab Nationalism was not a new ideology and was known throughout the Empire, but evidently, it was very weak, and remains so to this day. But that didn’t mean that it didn’t have its adherents. Arab Nationalism became a powerful force within the frightened Arab Tribal Beys, who were angered by what they saw to be essentially a governmental overreach.

Abdullah Bin Khazal was the founder of the Arab Liberation Army

The formation of the Arabistan Liberation Army in Ahwaz, Iran, by Abdullah Bin Khazal became a rallying point for the Shia Arab Nationalists. Ironically most intellectuals or supporters who answered this call to arms against a ‘foreign oppressor’ were Sunnis, and not Shias. Shukri Al-Quwalti and Izzat Darwaza became the leaders of the Anti-Ottoman Arab Resistance (AOAR) in Basra on the 27th of July, 1923, forming a caucus of Arab nationalists who were no committed to a violent struggle for independence against the Ottoman Empire. The AOAR also became the Ottoman Branch of the ALA in all essentiality. Arab Independence of course had little support among the populace, and the continued legitimacy of the Caliphate through the growing reforms, democracy and the victories in the Italo-Ottoman War and the Balkan War. But that didn’t mean that the populace couldn’t be brought into line with violence. Al-Quwalti was of course appalled at this line of thought, being a moderate nationalist all things considered, however men like Darwaza became proponents of this violent exchange of power.

Furthermore, many Anti-Semitic Arabs came to join the AOAR. Whilst most were fine with the quota system which allowed Jewish integration and immigration into the Ottoman Empire, some Arab Nationalists were extremely angered by the presence of new Jews in Palestine, Syria, Iraq and Hejaz, and as such, found themselves susceptible to AOAR propaganda.

The first attack by this group that would plague the Ottomans in the 1930s and 1940s would take place on the 3rd of September, 1923, when a small light bomb was detonated outside of the British Consulate in Baghdad. Only 2 people were killed around a dozen were injured during the blast attempt. At the time the Ottomans did not know the perpetrator of the attack, and an investigation was launched.

British Consulate in Baghdad

The Ottoman-Iranian Anti-ALA Campaign was in the making.” Origins of the Arabian Front of the Second Great War.

“The creation of the Ottoman Welfare State was intrinsically linked with the growth of political movements within the Ottoman Empire. In early 1923, the Ottoman Government decided to pass through the Local Election Bill, which passed through the Chamber of Deputies with relative ease, as it was one of Mustafa Kemal’s more popular proposals, even among opposition parties. The Ottoman Local Elections were to be held between Legislators, which were basically Ottoman Councilors, formed on the basis of British Councilors during British Local Elections. Furthermore, Ottoman Vice-Governors of Vilayets were also put up for Local Elections to be contested for. The Ottoman Local Elections unlike the British Local Elections, however were not direct elections. A list would be provided to voters, and the compiled votes was then collected, tabulated, and then depending upon the share of the vote per local district, Sanjak, Kaza or Vilayet, the amount of legislators, and vice-governors were distributed between the political parties. This was an incomplete and a flawed system, even though it was popular at the time.

As per the bill, the threshold needed to contest the local elections was also much lower than the threshold of the General and Senatorial Elections, making sure that a more proportional representation of the political parties involved could take place. On the 27th of August, 1923, the first Local Elections in Ottoman History took place with a turnout of 74.7%. Like expected, the ‘Big 3’ political parties in Ottoman politics – The Committee of Union and Progress (CUP), Liberal Union (LU) and Socialist Party (OSP) – gained the highest amount of Legislators and Vilayet Vice-governorships. 63% of all votes went to these parties. Worryingly for the Liberal Union, their increasingly pro-welfare view was challenged by the rural and conservative class, who were discontent with growing abolitions of Islamic judicial rules during the prison and justice reforms. This frustration was taken out against the Liberal Union by voting tactically in favor of the CUP, which allowed the CUP to gain the largest share of the Popular Vote. (23%).

![localelectionsottoman[2].PNG localelectionsottoman[2].PNG](https://www.alternatehistory.com/forum/attachments/localelectionsottoman-2-png.682597/)

Results of the 1923 Ottoman Local Elections

Another 19% of the Local Legislators and Vilayets were won by the political parties and groups that were represented within the Chamber of Deputies and Senate. However, after this, things start to become interesting. Greek Nationalism though muted after the increasingly democratic reforms of the Ottoman Empire was not dead, and anyone who thought that Greek Nationalism within ottoman lands was dead was a fool. Along with Armenian Federalists, Al-Fatat, and IMRO (All of which had nationalist tendencies, though most of them professed regionalism instead of nationalism during elections), the nationalist branch of the Ottoman Legislators during the Local elections won around 4% of the total electorate. The more conservative Ulema Councilors managed to win several legislator seats in Inner Arabia, Najd, and Hejaz, whilst other seats were dispersed between a vast myriad of other parties and independents.

The leader of the Greek Nationalist Party, Priest Chrysanthos of Trebizond resigned after the elections, even though most had thought that the party had performed admirably in the local elections. Chrysanthos was more of the opinion that his resignation would create a vacuum that would allow his ally and aid, Germanos Karavangelis to come to power. Karavangelis and Chrysanthos were both moderate nationalists and wished to only split from the Empire if the people supported it. But there was an undercurrent of hardline nationalists within the party, and this coup de grace which led to the consolidation of the moderate nationalists, as Karavangelis did come to power, led to the Greek Nationalist Party shifting from a right nationalist party into a center-left nationalist party instead.

Karavangelis was however worrying for the Ottoman government. He had been a keen supporter of the Macedonian Struggle for Greek Nationalists and before the advent of the Second Constitutional Era, he had been a supporter of a Russian-backed independent Republic of the Pontus. This position of Karavangelis changed with the advent of the Second Constitutional Era, yet the ottoman higher-ups remained wary of the known dissenter.

Nevertheless, despite the small hiccup that was the Greek Nationalist Party, the local elections were more or less successful, and though the Liberal Union did not gain the number of seats and legislators that Kemal thought they would, the ruling government certainly gained a great deal of legitimacy as the Ottomans conducted their first local elections, creating the basis of the Ottoman Local Level Legislative Elections in the future.” Mustafa Kemal Pasha: 1922 – 1928; The Maker of the Welfare State

Coming Up Next:-

The Chinese Civil War

Russian Developments

Ottoman Naval Developments

The Japanese Dilemma

Note: Some Information from Rivers of the Sultan by Faisal Hussain are included in this chapter, including the two maps.

“Until acquiring Dominion Status in 1907, Newfoundland and Labrador were mere colonies in the British Empire. One that was filled to the brim with white settlers yes, but just another colony. But the achievement of dominionship in Newfoundland opened up the colony to a whole new myriad of dominion style politics. Under Sir Robert Bond, the Newfoundland Dominion reached the pinnacle of its economic growth. Railroads were constructed, a mix of liberal free trading and protectionist policies made the fisheries that the island nation was so dependent on grow to a whole new height. However, his rather large disposition towards free trade hurt the rights of the Fishermen in Newfoundland, and he was defeated in 1909. He was succeeded by William Coaker, and then Coaker himself was succeeded by Edward Morris, a Catholic from the pro-Catholic People’s Party of Newfoundland.

When the Great War broke out in 1915 its cause was met with near unanimity within Newfoundland. Recruiting was fast, and a general feeling for ‘King and Country’ did reign supreme within the new dominion, and around ~7,000 men volunteered for the Newfoundland Army within a month, and another 2000 men joining the Newfoundland Navy. Around 4000 other Newfoundlanders joined the British war effort through the Canadian or British forces as well. For a country of just ~250,000 people, a manpower pool of ~15,000 men joining the war effort was a legendary undertaking in simply fact of numbers.

However, whilst the war was popular early on, and to an extent, remained popular, the governing government had fallen with accusations of wartime corruption and giving more fishing rights to the Canadians. The Royal Governor, Sir Walter Davidson did try and make the issue resolved, but his establishment of the Newfoundland Patriotic Union as a non-partisan base of debate only made sure that political tensions in the Dominion rose. As a result, in early 1917, an all-Party National Government was formed. Unlike Canada, the country did not get into a major conscription crisis, however, it did force the Fisherman’s Party to dissolve into history, as a schism arose within the party as its leaders supported conscription whilst its members opposed conscription.

Newfoundland troops during the Great War

During the Great War, the Newfoundland Regiments in service of the British Empire performed admirably. They were mostly deployed to the African Front, where they played a key role in the defeat of German East Africa and German Kamerun. 2 Regiments also fought in the Western Front Alongside British and French forces. In particular, the small Battle of Charleroi, which happened during the Second Battle of Waterloo as a sub-battle saw 1200 Newfoundland soldiers defend the small Belgian village against a German assault seven times before giving ground. In Newfoundland, the Battle was seen as a romantic battle, a last stand of the Newfoundlanders if you will, and like Canada and Australia, the Dominion of Newfoundland felt an upswing of nationalism towards their own countries.

The remnants of the fisherman’s union joined with the Liberal Party of Newfoundland to form the Liberal Reform Party of Newfoundland, led by one Richard Squires, who won the 1919 General Elections rather handily. Squires was and remains a controversial figure in Newfoundland History. His early reforms did expand education for all within the Dominion, and his development of the Humber River in Newfoundland led to some amount of economic growth that saw the growth of the fisheries. However, these reforms also led to a price collapse of the northern fisheries, which made the man extremely unpopular in the majority of the electorate after 1921. The growing anti-Communist surge in the Dominion also targeted Squires when he nationalized the railway networks on the island in 1922. Italian-Newfoundlanders, already having a small community in the island were virtually thrown out due to anti-communist paranoia, and such a nationalization scheme only made Squires more distrusted and more hated among the general population.

Richard Squires

When in 1923, when new elections were called for August of the year, the Newfoundland People’s Party, or the Liberal-Labour-Progressive Party as they were called in an official capacity, had rebounded from their fall to power in 1917. Largely due to the efforts of one man and his supporters – William J. Higgins. Working as a clerk for a time in the party, he had joined the Royal Navy during the Great War and had distinguished himself during the Battle of Devil’s Hole, winning several military award along the way. After a general ceases in hostilities he returned to Newfoundland and was elected the Speaker of the Newfoundland Assembly in 1918. In 1919, he was elected the leader of the People’s Party after the failure of the party to win the 1919 elections. A man learned in the ways of law and justice through a degree he had earned, and a man with a military record, he drew massive support from the legalistic and veteran populace of the Dominion. Furthermore, his party’s pro-Catholic position meant that the support of the Catholics – mainly the Irish Newfoundlanders and the Scottish Highlanders of Newfoundland – was also assured.

William J. Higgins

That was not enough to win an election with a landslide, but luck was in favor of Higgins. Just one month before the elections, Squires was hit with a massive barrage of corruption allegations. None of them were ever proved, but the allegation of accepting bribes and giving nationalized business’s to the highest bidder hurt the reputation of Squire greatly, and even the most radical anti-communist started to look at the People’s Party, a Social Democratic Party, with some speculative gaze. The elections were not polarized in the sense of polarized politics like the one going on in America, or even other polarized nation-states, but it was filled with tensions, that was for sure.

Higgins’s People’s Party managed to come out on top, and won 21 of the 36 seats in the Newfoundlander Parliament, winning an absolute working majority. The greatest problems now facing Higgins as Prime Minister of Newfoundland were the two hot-button issues of Full Women’s Suffrage and the Labrador Border Dispute with Canada. Squires had implemented a partial women’s suffrage scheme in 1921, and around 92% of the women that were given the right to vote did do so in 1923. The rest of the women community were now agitating for full suffrage. This time, the Newfoundlander Suffrage Community drew inspiration from the United Kingdom, the Empire of Danubia and the Ottoman Empire. The Ottomans and the British had given women the right to vote already and the Danubians were well on track to give all their women the vote by the 1924 Legislative Elections. Though the orientalist annotations did offend many Ottoman citizens, the slogan ‘If the Turk Can Vote, why can’t we?’ became a popular slogan among the suffrage movement.

Higgins responded by creating the Suffrage Committee within the Parliament. The Committee filed a draft on the 28th of October, 1923 declaring that a full suffrage would be achievable by the next year, and that by and itself ended the issue of suffrage for women in the island.

The second and more pressing issue was that of Labrador. Labrador had been a long-standing dispute between Quebec and Newfoundland ever since 1867 when the Canadian Confederation was created. The Quebec Boundary Extension Act of 1912 which included Ungava into Quebec created a very loose border between Labrador and Newfoundland, sparking the dispute, as the two sides started to create overlapping claims against one another. Newfoundland asked the Canadian government for mediation between the Province of Quebec and Newfoundland in 1922 under Squires, however Quebec’s Premier, Louis-Alexandre Taschereau was opposed to this move, and instead moved the decision to the British Privy Council, making this regional headache a headache for London as well.

Reginald McKenna, the British Prime Minister directed the Privy Council to make a fast and sound decision ‘that would not alienate’ either Ottawa or St. John. Canada argued in front of the Privy Council that Newfoundland had only received a strip of land extending 1.6 kilometers from the coastline so that it could control the fisheries of the region, and that the rest of Labrador was a part of Quebec, and therefore a part of Canada. Newfoundland instead argued that the term coast which was used in communications between different officials throughout the Empire in regards to the Dominion of Newfoundland showed that a larger portion of the territory was meant rather than just a coastal strip. In order to make sure that the British were not implicated in an unpopular decision, the government made sure that the key decision judges of the Privy Council were Australians, New Zealander, and South Africans. And in the end, the Council deemed on the 18th of November, 1923 that the Labrador Dispute was in favor of Newfoundland because even the 1912 Quebec Extension Act had a small clause denoting that the land was rightfully Newfoundlander. This clause had been inserted by the Quebecois government in 1912 to make sure that there was no flare-up of tensions, but in the end, it had worked against them and their interests. Taschereau was livid, but he could do nothing much and had to accede, though he did withdraw his support of Prime Minister MacKenzie King, whom he viewed to have done little to back up Canadian/Quebecois claims. This led to a small political crisis within the Liberal Party, which saw King’s government fall during the Labrador Dispute. King was moved against with a motion of no confidence, and a dark horse candidate within the Liberal Party, Hewitt Bostock became Prime Minister of Canada, surprising many, as many thought that the more prominent candidates such as Charles Stewart or Ernest Lapointe would become Prime Minister. A more moderate candidate, Bostock however proved to be the least disuniting figure to rally around leading him to become Prime Minister.” Newfoundland and Canada in the Interwar Era: A History of Tumultuous Relations

“Ottoman Mesopotamia or Iraq, depending upon the person and record, entering into 1923 was a changing place. Having been a part of the Ottoman Empire since the 1630s, the area had many a historical links to other powers in the region, like Iran and the Arab Interior. However aside from the rebellion of the Iraqi Beys in the early 1800s, Iraq had remained a generally peaceful region in the Ottoman Empire. This relative peace in the region did allow for greater concentration of wealth and coming into the 1908 Revolution, Iraq was one of the richer areas of the Empire, with Baghdad being almost as grand as Constantinople itself, though with its own unique charm, and obviously less populated.

The ascension of Suleiman Nazif Pasha as the Governor of Baghdad in 1916 had transformed the Baghdad Vilayet into an administratively competent regime as well. Though Suleiman Nazif hadn’t been particularly good at any sort of administrative affairs before during his stay as Governor of Basra, Syria and the Archipelago Vilayet, he had learned from his mistakes, and by the time he took power in Baghdad, he had become a competent administrator in his own right. Furthermore, he was an avid writer, and having mastered Arab, Persian and French together with his native Anatolian Turkish, he was a highly learned man.

Suleiman Nazif Pasha

Nazif Pasha was a man who encouraged self-sufficiency and he wanted to make the best of the current economic miracle going on in the Ottoman Empire. He was also highly critical of the Liberal Union’s ruling government (he was a member of the CUP party) for allowing extra rights to the British for their oil exploration within the Baghdad Vilayet. Though obviously not sanctioned by either London or Paris, British and French oil hunters within the Ottoman Empire had a notorious reputation as being highly disrespectful to the Muslim population of the Empire. Further than just behavioral problems, Nazif Pasha attacked the belief that a deal with the west was required for oil exploration in the empire. He was firmly in the camp with the belief that allowing concessions to London and Paris regarding oil would come back to bite the Ottomans later.

When a small French company was arrested in Baghdad for harassing a small caravan of Bedouins, the French company demanded to speak with the Governor, demanding their release. In this event the Governor simply said no and did not even deign to meet the company, instead ordering them to go through the legal requirements. He became famous for his anti-European rhetoric at the time.

Furthermore, Ottoman Iraq remained economically lucrative. For the Ottoman Empire, Baghdad was what Palmyra was to the Roman Empire, as a vital link between Ottoman Anatolia and the Persian Gulf. Under Ahmet Riza, Ottoman Iraq had undergone a new revitalization of the Euphrates and Tigris Trade Routes. Latakia and Tripoli were once again connected to the Persian Gulf through Aleppo and Birecik, increasing intranational trade, and river ports were constructed in Ana, Mosul, Hit, Baghdad, Falluja, Ridwanniya, Hilla, Qurna, all the way to Basra, where a major port had been built under the command of Ali Kemal in 1913. This interconnectedness of river ports all the way to Basra facilitated a major growth in economic activity throughout the region, and became one of the key players of the Ottoman economic surge in the region.

Ottoman Riverports in Ottoman Iraq

Riza had also been instrumental in the reconstruction of the Main Euphrates Channel, which allowed for more direct trade between Arja and Rumahiyya, and allowing for greater economic mobility in the region as a result. Drought, and the shifting river had made the canal invalid in the early 1700s and it was abandoned. But with advanced canal building and construction techniques of the early twentieth century, reopening the canal became possible and was pursued by the Ottoman government full steam ahead.

The Euphrates Canal

The Ottoman Agricultural Revolution spread into Iraq as well. The Marshes and Wetlands that surrounded the two great rivers of Mesopotamia were perfect for extra irrigation to supply greater number of farms, and was used as such. Farming production increased by 76% between 1915 and 1920 within Ottoman Iraq, signaling an extreme rise in agricultural potential in the region. The growing urbanization of the 3 Iraqi Vilayets also meant that more and more tracts of land became available for agricultural use as many villagers or nomads sold the lands they owned in the periphery and then used said money to immigrate to the three great cities of Baghdad, Mosul and Basra within Ottoman Iraq.

Coupled with all of these new economic factors, the Ottomans also experienced a massive shipping boom in Iraq. Coupled with the growth of internal river ports once more, the completion of the Basra International Port meant that the shipping lanes in the Persian Gulf became of utmost importance to the Ottoman Economy again, and money funneled down into the region from Constantinople. Shipping business’s cropped up throughout Basra and the River Ports, and civilian ship companies began to sniff for profit in the region. Ferries from Basra to Muscat and Bombay became regular as the city exploded in size and wealth due to the explosion of shipping throughout the region. This facilitation of water transport also led competition between the shipping industry and the railway industries. The Railways of Iraq were almost all concentrated near the Euphrates and Tigris, and at times, simply travelling by ship was more cheap or faster in comparison to trains. The railway companies responded by receiving a grant from Constantinople to build a cross desert railway path all the way to Damascus, making time for travelers from Basra to Syria cut almost by half. The Shipping companies responded by constructing faster transport ships for the rivers. This sense of competition greatly benefitted Ottoman Iraq’s economy, as competition gave way to innovation, and innovation gave way to increased wealth.

But underneath all of these developments, most of which were good, a more sinister development was taking place. The Ottoman involvement in putting down the Arabistan Crisis in Iran managed to make many of the Shia Arabs living on the Ottoman-Iranian Border feel threatened, and the small tribal beys and amirs of the Iraqi tribes, feeling their power threatened, began to advocate for a complete separation of Iraq from the Ottoman Empire, in line with Arab Nationalism. Arab Nationalism was not a new ideology and was known throughout the Empire, but evidently, it was very weak, and remains so to this day. But that didn’t mean that it didn’t have its adherents. Arab Nationalism became a powerful force within the frightened Arab Tribal Beys, who were angered by what they saw to be essentially a governmental overreach.

Abdullah Bin Khazal was the founder of the Arab Liberation Army

The formation of the Arabistan Liberation Army in Ahwaz, Iran, by Abdullah Bin Khazal became a rallying point for the Shia Arab Nationalists. Ironically most intellectuals or supporters who answered this call to arms against a ‘foreign oppressor’ were Sunnis, and not Shias. Shukri Al-Quwalti and Izzat Darwaza became the leaders of the Anti-Ottoman Arab Resistance (AOAR) in Basra on the 27th of July, 1923, forming a caucus of Arab nationalists who were no committed to a violent struggle for independence against the Ottoman Empire. The AOAR also became the Ottoman Branch of the ALA in all essentiality. Arab Independence of course had little support among the populace, and the continued legitimacy of the Caliphate through the growing reforms, democracy and the victories in the Italo-Ottoman War and the Balkan War. But that didn’t mean that the populace couldn’t be brought into line with violence. Al-Quwalti was of course appalled at this line of thought, being a moderate nationalist all things considered, however men like Darwaza became proponents of this violent exchange of power.

Furthermore, many Anti-Semitic Arabs came to join the AOAR. Whilst most were fine with the quota system which allowed Jewish integration and immigration into the Ottoman Empire, some Arab Nationalists were extremely angered by the presence of new Jews in Palestine, Syria, Iraq and Hejaz, and as such, found themselves susceptible to AOAR propaganda.

The first attack by this group that would plague the Ottomans in the 1930s and 1940s would take place on the 3rd of September, 1923, when a small light bomb was detonated outside of the British Consulate in Baghdad. Only 2 people were killed around a dozen were injured during the blast attempt. At the time the Ottomans did not know the perpetrator of the attack, and an investigation was launched.

British Consulate in Baghdad

The Ottoman-Iranian Anti-ALA Campaign was in the making.” Origins of the Arabian Front of the Second Great War.

“The creation of the Ottoman Welfare State was intrinsically linked with the growth of political movements within the Ottoman Empire. In early 1923, the Ottoman Government decided to pass through the Local Election Bill, which passed through the Chamber of Deputies with relative ease, as it was one of Mustafa Kemal’s more popular proposals, even among opposition parties. The Ottoman Local Elections were to be held between Legislators, which were basically Ottoman Councilors, formed on the basis of British Councilors during British Local Elections. Furthermore, Ottoman Vice-Governors of Vilayets were also put up for Local Elections to be contested for. The Ottoman Local Elections unlike the British Local Elections, however were not direct elections. A list would be provided to voters, and the compiled votes was then collected, tabulated, and then depending upon the share of the vote per local district, Sanjak, Kaza or Vilayet, the amount of legislators, and vice-governors were distributed between the political parties. This was an incomplete and a flawed system, even though it was popular at the time.

As per the bill, the threshold needed to contest the local elections was also much lower than the threshold of the General and Senatorial Elections, making sure that a more proportional representation of the political parties involved could take place. On the 27th of August, 1923, the first Local Elections in Ottoman History took place with a turnout of 74.7%. Like expected, the ‘Big 3’ political parties in Ottoman politics – The Committee of Union and Progress (CUP), Liberal Union (LU) and Socialist Party (OSP) – gained the highest amount of Legislators and Vilayet Vice-governorships. 63% of all votes went to these parties. Worryingly for the Liberal Union, their increasingly pro-welfare view was challenged by the rural and conservative class, who were discontent with growing abolitions of Islamic judicial rules during the prison and justice reforms. This frustration was taken out against the Liberal Union by voting tactically in favor of the CUP, which allowed the CUP to gain the largest share of the Popular Vote. (23%).

Results of the 1923 Ottoman Local Elections

Another 19% of the Local Legislators and Vilayets were won by the political parties and groups that were represented within the Chamber of Deputies and Senate. However, after this, things start to become interesting. Greek Nationalism though muted after the increasingly democratic reforms of the Ottoman Empire was not dead, and anyone who thought that Greek Nationalism within ottoman lands was dead was a fool. Along with Armenian Federalists, Al-Fatat, and IMRO (All of which had nationalist tendencies, though most of them professed regionalism instead of nationalism during elections), the nationalist branch of the Ottoman Legislators during the Local elections won around 4% of the total electorate. The more conservative Ulema Councilors managed to win several legislator seats in Inner Arabia, Najd, and Hejaz, whilst other seats were dispersed between a vast myriad of other parties and independents.

The leader of the Greek Nationalist Party, Priest Chrysanthos of Trebizond resigned after the elections, even though most had thought that the party had performed admirably in the local elections. Chrysanthos was more of the opinion that his resignation would create a vacuum that would allow his ally and aid, Germanos Karavangelis to come to power. Karavangelis and Chrysanthos were both moderate nationalists and wished to only split from the Empire if the people supported it. But there was an undercurrent of hardline nationalists within the party, and this coup de grace which led to the consolidation of the moderate nationalists, as Karavangelis did come to power, led to the Greek Nationalist Party shifting from a right nationalist party into a center-left nationalist party instead.

Karavangelis was however worrying for the Ottoman government. He had been a keen supporter of the Macedonian Struggle for Greek Nationalists and before the advent of the Second Constitutional Era, he had been a supporter of a Russian-backed independent Republic of the Pontus. This position of Karavangelis changed with the advent of the Second Constitutional Era, yet the ottoman higher-ups remained wary of the known dissenter.

Nevertheless, despite the small hiccup that was the Greek Nationalist Party, the local elections were more or less successful, and though the Liberal Union did not gain the number of seats and legislators that Kemal thought they would, the ruling government certainly gained a great deal of legitimacy as the Ottomans conducted their first local elections, creating the basis of the Ottoman Local Level Legislative Elections in the future.” Mustafa Kemal Pasha: 1922 – 1928; The Maker of the Welfare State

Coming Up Next:-

The Chinese Civil War

Russian Developments

Ottoman Naval Developments

The Japanese Dilemma

Note: Some Information from Rivers of the Sultan by Faisal Hussain are included in this chapter, including the two maps.

thanks! I do intend to keep Newfoundland independent ittl.Pretty cool you covered such an obscure subject - Newfoundland politics!

Will Newfoundland still collapse. If so can it avoid becoming Canadian?any predictions?

Will Newfoundland still collapse. If so can it avoid becoming Canadian?

thanks! I do intend to keep Newfoundland independent ittl.

Thank you that's a high compliment! Unfortunately I don't have other timelines right now.Hello I have been reading you stories

The Duke of Wellington,Osman reborn,The Russian story I forgot its name and of course the new Emperor of heaven.I love them

I wanted to ask if you have stories other then them I would like to read them

*Shifty eyes* So he says. Not that your other stuff was bad, quite high quality in fact. You are just a man with too many ideas and not enough time.Thank you that's a high compliment! Unfortunately I don't have other timelines right now.

Nice to see Newfoundland and Iraq covered. The AOAR and ASK don't sit well with me.

That's true hehe 😅*Shifty eyes* So he says. Not that your other stuff was bad, quite high quality in fact. You are just a man with too many ideas and not enough time.

Thanks. Yeah AoAR will remain a pain until the end of ittl ww2Nice to see Newfoundland and Iraq covered. The AOAR and ASK don't sit well with me.

Great chapter

What about North Africa Muslim countries that are under France will they get their Independence.

What about North Africa Muslim countries that are under France will they get their Independence.

Indeed they won't.Don't think Britain'll take that bombing too kindly

We will see! French colonial developments will be coming.Great chapter

What about North Africa Muslim countries that are under France will they get their Independence.

Threadmarks

View all 110 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Holidays in the Ottoman Empire Chapter 66: The Swedish Republic of Ostrobothnia & Growing Disillusionment Look into the future [4] Chapter 67: cultural update – The Top 3 Sports in the Ottoman Empire turtledoves 1926 Ottoman General Elections Map. Chapter 68: African Rumblings. Chapter 69: Land of the Unfree

Share: