Chapter 5: Another day

Church bells rang, people cheered in the streets and toasted in feast halls and taverns. From Lübeck to Danzig, from Bremen to Cologne there was an uncontrollable joy as word spread. It was not word of something that usually warranted celebration, there had neither been an important marriage, the birth of some royal prince or the beatification of a new saint. No, what brought forth all this exaltation was something that usually produced sadness and mourning. What was celebrated was not life, but death. In the late fall of 1375 word quickly spread across northern Europe: Valdemar IV of Denmark, the evil King who had terrorized much of northern Germany for three decades, had finally been taken from this world and, hopefully, straight into the maw of Lucifer. It is a testament to the King’s success in his struggles against the Hansa and his many other enemies that his end resulted in such unregulated celebration, totally ignoring how it may offend the King’s son who now stood to ascend as sole ruler of Denmark, the Kingdom which had been reborn during Valdemar’s reign. Emperor Charles IV had at least kinder words for the departed, proclaiming in a letter sent shortly after the news reached him that: “We, the Emperor, and he, the King of Denmark, were through long times closely connected to each other by brotherly feelings.”

In Denmark, the cognomen ‘Atterdag’ is usually interpreted as ‘day again’, referring to the King bringing Denmark out of the ‘night’ of the Kingless time. In German the nickname can however be understood as referring to the biblical Judgement Day, painting the King as an apocalyptic figure.

The King had been active and healthy until shortly before his death. In October of 1375, he travelled to Gurre castle in northern Zealand, perhaps to spend some time with his supposed mistress ‘Tovelille’. While staying in his favorite holding, the King suddenly came down with an unknown illness, rendering him weak of body but in no dulling way his mind. There was time enough for both the King’s closest councilors and the Junior King to be summoned. Christopher would be Valdemar’s only family member present when he died, Queen Helvig had passed the year prior, his eldest daughter Ingeborg already in 1370, while Margaret was in Norway. His seven grandchildren were in Lolland, Mecklenburg, and Norway respectively. Valdemar spent his last days reiterating that his men should serve Christopher as loyally and dutifully as they had him. He reminded them that Christopher was already crowned King, and offered some final advice to his son himself. Then finally on the 28th, the King drew his final breath, and with-it Christopher became sole King of Denmark, as Christopher III.

Unlike his father, who had come into royal dignity from previously having had little but his name, Christopher ascended from a position of strength. He was now 34 years old, and had nearly 20 years of diplomatic, military, and governing experience, having taken part in his father’s Kingdom-building project from his teen years onwards. Ingeborg of Mecklenburg, now sole Queen of Denmark, had already provided him and the realm with potential heirs, in the form of the sons Valdemar, Erik and Magnus – the last one named after the Queen’s uncle. Earlier the same year as Christopher became King, the Queen had also given birth to a daughter who was given the name Euphemia after Ingeborg’s mother and her husband’s grandmother. Christopher had served as de-facto regent during his father’s absence during the second Hansa war, and as official co-ruler for the last four years, there could be little dispute over Valdemar’s succession. Thus, even though many of the Kingdom’s enemies cheered and breathed sighs of relief, with their next breaths they prepared themselves for the continued onslaught of the new sole King.

The year before Valdemar Atterdag’s death, there had been another royal casualty; the former King Magnus of Sweden presumably drowned as his ship sank in Bømlafjorden outside the western coast of Norway. Magnus’ death caused the conflict between Haakon of Norway and Albert of Sweden to again blossom up. The later demanded that the provinces ceded to Magnus after the peace of Stockholm be returned, while Haakon refused to give them up. The two Kings bickered, but the nobility of Sweden still preferred the current status quo, and without their support the conflict became little more than a series of minor border skirmishes and raids. There was some spillover in the Danish-controlled provinces of Finnveden and southern Västergötland, those that had come under Danish control through the still unratified Aalholm tractate, especially once King Valdemar died and Albert likewise demanded that these lands be returned. Again, this conflict became little more than a border skirmish, and the Danish position was never truly threatened by what little forces Albert could muster. In fact, the reignition of the conflict suited Christopher fine. With a potential enemy to the north distracted by a low-intensity conflict, he could keep his attention on the south. King Valdemar had not lived to see the reunification of Sønderjylland with the rest of the Danish Kingdom, but Christopher pledged on his deathbed to carry on his endeavors. Firstly though, there were some internal matters that needed tending to.

A few decades after Magnus’ death, a Russian manuscript would invent the myth that the King had survived his shipwreck and gone into exile as an orthodox monk. There is little veracity to this legend, and it was most likely invented to mock the King who’d launched crusades against the Orthodox Russians in his early reign.

Since 1282 Danish Kings had been expected to sign a ‘håndfæstning’ upon their ascension, a document that usually limited their powers over the nobility and guaranteed that their privileges were not overstepped. Now that Christopher was to rule alone, most of the Danish magnates believed it proper that he sign one such document himself, but the King believed that there was no need for this. Valdemar’s håndfæstning had been atypical, it was signed as late as 20 years into his rule, in 1360. It was known as the ‘Decree of the King’s peace’ and was a mixed document in terms of whom it favored. In some regard it limited the King and his officials’ powers over his noble subjects. It stipulated that the King was to call a ‘Danehof’ – a sort of parliament, each midsummer and protected people who took legal action against the King from illegal retribution. In other regards though, it increased royal power greatly. Notably, it explicitly forbade rebellion against the King and stipulated that loss of life and land was the punishment such crimes. In a sense, this made all the regulations on the King’s powers meaningless, for even if the King was believed to be unjust, it was now illegal to rebel against him. The decree had been signed both in the name of King Valdemar, and the at that time 19-year-old Duke of Lolland, now King, Christopher. As such the King felt that the issue of his håndfæstning had already been resolved, and he was not interested in signing a new one that risked re-legalizing rebellions against the King. For the nobility however, getting rid of that article was key, especially since King Valdemar had violated just about every other paragraph of the håndfæstning with impunity, setting a precedent no nobleman wanted to see normalized.

For all their issues with the King’s degree of authority, the current opposition in Denmark had very little solid ground to stand on. Christopher had already been crowned, so refusing to hail him as King was not an option. More importantly perhaps, even when he was merely Junker, Christopher had enforced the right so seize lands of rebellious nobility, particularly doing so in Jutland following the peace of Stralsund. There were still noblemen in active rebellion on the peninsula, but they were cut off from their traditional ally, the Counts of Holstein, who had been forced back to a defensive position in Gottorp. Right before the King’s death, the rebels’ position had suffered another hard blow, as the King managed to convince Pope Gregory XI to excommunicate all the nobles who still were in rebellion against him. As such Christopher’s first action would be to carry out his father’s final and now church-approved vengeance against the Jutish nobility, before turning his attention to Gottorp. With the excommunication in place, Christopher’s methods became increasingly brutal. Many Jutish rebels were executed, but those who surrendered quickly he spared, for the did not wish to start his sole reign with a bloodbath. In fact, the new King even rewarded the nobles who remained loyal to him, returning some of the seized estates – though not nearly as much as most would’ve wanted. Christopher also gave grants to the church for them to hold masses for the departed Valdemar. The celebrations on the continent had not only been insulting to Christopher, they’d also been embarrassing, to think that his father had been so hated that men were openly cheering his death. Tending to his father’s memory and trying to posthumously improve his reputation would be a key secondary objective for Christopher’s reign.

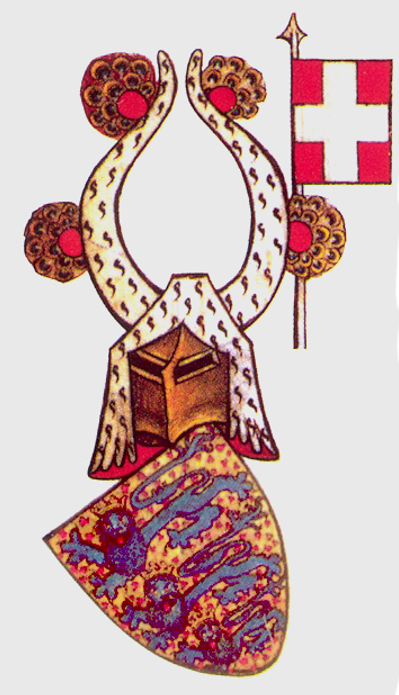

The decree of the King’s peace from 1360.

Christopher spent most of 1376 finally pacifying the last parts of Jutland with a mixture of brutality and mercy, eventually the entire northern part of the peninsula was pacified. It had come at a cost though, while Count Nicholas hadn’t been able to launch any serious counterattack, he had been given precious time to prepare himself for the King’s own advance. Nicholas wasn’t as experienced nor as skilled a commander as his older brother Henry had been, but he was still determined to defend the lands he claimed as his own. His plan was to hold out in Gottorp until some foreign power would intervene on his side, hopefully the Hansa, or until another rebellion could arise in Denmark. Danish forces soon moved down south and occupied the town of Schleswig, from it’s walls the castle of Gottorp was clearly visible, standing on a small island in the middle of the Slien fjord. The besiegers could easily cut off the castle’s northern side, but to cut it off from the south would require a fully-fledged invasion of the Holsatian heartlands, something Christopher was wary to attempt. Additionally, because it was surrounded by water, the castle had ample opportunity to be supplied from the sea. The stymied attackers could only watch from their base in Schleswig as friendly ships unopposed sailed past them to deliver supplies to the defenders.

It was thus clear that Christopher’s forces weren’t going to take Gottorp by simply blocking off the north, and if they retreated the door was open for more Holsatian incursions. Invading Holstein to cut the castle out from the south was likely impossible without major support from some German ally, but in the current situation it was unclear who this would be. Christopher made sure to keep on good footing with the Duke of Saxe-Lauenburg. But convincing him of raising arms against his empowered vassals was hardly realistic. The sea then appeared as the most viable option for the Danes, though it came with its own sets of limitations. Getting ships into Slien would be a risky operation, it came with every opportunity for ambushes from the many hiding-places of the fjord. In addition, the ships which the Danes disposed over were mainly troop carriers, which in battle served mainly as a mode of transportation for soldiers to enter the enemy’s own ships. That would do little good against a castle like Gottorp. Ideally, the Danes would use newer ships, laden with siege weapons like early cannons, but getting those ships would be tricky. The best harbors in the Baltic were controlled by the Hansa and though peace currently reigned between the league and Denmark, that didn’t equate a willingness to provide their former enemy with weapons.

A medieval siege more often considered of long periods of waiting, rather than large-scale assaults.

The problem was that it served Hanseatic interest that Gottorp remain in Schauenburger hands, not only did the Counts serve as a useful counterbalance to Danish power, total control over the Duchy would also empower the Danish presence in the Baltic Sea – possibly letting them threaten Lübeck itself in the worst case. Under the reign of King Valdemar, the mere suggestion of providing warships for the Danes would probably have been met with an uproar from the citizens of Lübeck, but the new King didn’t quite have his father’s fierce reputation. After all, it was Christopher who had given Henning Podebusk free hands to work out the, ostensibly, favorable peace of Stralsund with the Hansa, perhaps he was a man they could work with. Indeed, it was none other than Podebusk whom King Christopher dispatched to lead a new diplomatic delegation to Lübeck, hoping to work out a deal to get him the weapons needed to crack this final nut.

Glambæk was a heavily fortified castle on a minor isthmus on the southern shore of Fehmarn. It was also a strongpoint that was heavily contested during the reign of Valdemar Atterdag. At first held by the Counts of Holstein, King Valdemar besieged and seized the castle in 1358, but merely the year after, Count John of Holstein-Kiel took it back for himself, only to die the year after and again having the castle fall under Danish rule. The island of Fehmarn itself was traditionally considered part of the Duchy of Schleswig, although it was certainly it’s most periphery constituency, located much further to the east in the Baltic Sea than the Duchy’s mainland, closer to Holstein and the Danish Island of Lolland. The castle looms over the Bay of Lübeck, and many ships sailing to or from the city will likely come close to Glambæk’s walls. In short, Danish control over the island was a constant worry for the council of Lübeck, and as such for the Hanseatic League in its entirety. When the prospect of a complete Danish reconquest of Schleswig became reality, these worries doubled. It wasn’t long before Podebusk realized that value of Glambæk as a bargaining chip. With the same boldness he had used in the negotiations at Stralsund, Podebusk offered pawning the Island, including Glambæk itself, to the city of Lübeck in return for the ships and weapons needed to win the siege of Gottorp.

The reaction was strong both in Lübeck and Denmark upon this suggestion. In Lübeck the pros and cons were weighed against each other, like silver coins on the scales during a precious bargain. In Denmark, many considered the suggestion preposterous and believed Podebusk to far be overstepping the authority of his office to even suggest pawning off a piece of the realm. Christopher was however not as negatively set to the idea. Letting go of an island his father had fought for didn’t appeal to him, especially since it’d mean that all Sønderjylland still wouldn’t be under the crown, but Gottorp was by any measure a more important target than Glambæk. With Gottorp under his control the Kingdom’s southern border could finally be secured, Holsatian influence and ability to support Jutish rebels could be ended. And of course, just because a province is pawned doesn’t mean it is gone forever, if his father’s reign had proven anything, it could always be retaken – by force, if necessary, when the time came.

Later reconstruction of how Glambæk may have looked in it’s medieval form.

It's likely that Podebusk also brought up the implication of force during his negotiations, after all the Hansa would like to keep their pawned Scanian towns, wouldn’t they? It would be a shame if the King, with his hopes of seizing Gottorp dashed, decided to turn his forces somewhere else. Naturally Podebusk wasn’t this blunt in his choice of words, but the power balance between the Hansa and Denmark was far from one-sided, and thus could add weight in negotiations when necessary. And so, after many negotiations, the terms were finally laid out. The city of Lübeck would have Fehmarn pawned to it for 40 years, after which the King of Denmark reserved the right to redeem it for a large sum of money. In return, Lübeck would outfit twelve warships with weapons, supplies and crew and put these under Danish command. The negotiations finished in 1378, with the transfer to take place the next year. The Lübeckers believed that they had made the right choice, with Fehmarn as a forward base, they could finally feel safe from any potential Danish seaborne attack, and the island would serve as another base to dominate the Baltic from. Additionally, many felt that the negotiations with Christopher had been far more pleasant than those with Valdemar, perhaps this was the beginning of a fruitful relationship with Denmark, that was certainly good news for the hold on the Scanian coast. As for the Danes, there were mixed reactions. Many felt insulted that the King didn’t trust his own men able to seize Gottorp for himself and disparaged at him pawning of pieces of the Kingdom – it reminded them all too much of his disastrous grandfather and namesake. When the King heard protests from his own men, he supposedly responded that his father had pawned Estonia for the sake of winning Denmark, so why shouldn’t he pawn Fehmarn for the sake of winning Sønderjylland?

Most of the complaints however fell silent when the fleet arrived. It was made up of large, heavy cogs, upon which both traditional siege weaponry and modern black-powder weapons were mounted. Hanseatic warships had often been a frightening sight for the Danes, but these ones had the colors of Denmark fluttering from their masts. Now it was Denmark’s foes who would tremble in fear, and tremble they would. In the summer of 1379, the new Danish warships carefully sailed into the narrow fjord of Slien, almost to big to be able to maneuver properly, the slowly snaked their way through the twists and turns of the waters. Eventually, they reached their target at the end of the fjord. The Danish forces occupying Schleswig town met their water-bound allies with cheers, while the defenders of Gottorp despaired at the sight of the new weapons turned at them. The siege continued for a short period, but Holsatian morale dropped to a new low. Not only were they facing a much-reinforced enemy, the new Danish naval supremacy meant that supplying the castle was all but impossible. Soon the defending commander offered to surrender with honor, and he and his men were allowed to leave unmolested with weapons and colors, though utterly defeated in spirit. It is said that many of the men cried as they passed south in Holstein, abandoning the last part of the Duchy they had fought over for half a century. With the news of victory, any doubt that had previously existed about the King’s judgement evaporated. Church bells were ordered to be rung, as news spread of the final defeat of the German invaders. Christopher was hailed as a great restorer, as people forgot about the pawning of Fehmarn, but the island would remain a personal blemish for the King for as long as he lived. Nevertheless, mainland Schleswig was again fully under Danish control, now remained only to be seen if they could hold it. Christopher made sure that funds were diverted to keep a permanent garrison in the castle, as peace finally seemed to return to the Danish Kingdom. Time would tell how long it was to last.

Hanseatic cogs were mainly cargo ships but could be put to great military use with the right equipment and crew.