Theresian Military Academy, Wiener Neustadt, Austro-Hungarian Empire, December 17th 1906

Lance-corporal Müller was aghast. “You must be bluffing.”

“I am not! This is one of our best designs!” Alfred Ramberg, his Austrian counterpart, replied as he smiled on the fresh snow. His joy was a definite contrast to the metal plates he was wearing, which seemed to flare out in certain places and made him look like a cross between a knight and a mad, middle-aged ballerina.

Müller could only palm his face in embarrassment. After five hundred thousand Marks as a loan, this is what we getting out from it!? “And what would happen if an enemy spots you in the snow and aims in a second?”

“Aha, watch this! This does seem clunky, but actually…” And to Müller’s surprise, the metal plates seem to buckle and reform as the wearer turned his body flat on the earth. “Its collapsible! The hinges are at the exact places to give out full movement, and now the cover forms a barrier against any oncoming bullets. Do you see that hole there?”

Müller nodded, not wanting to give out how this suspicions regarding the small hole in the side plate and… bathroom problems.

“Now, if I can just do this…” and with a speed that indicated the steel of a soldier’s training, Alfred pushed out his rifle barrel through the opening and pulled the trigger. “And with the fringed skirt up there, my eyes are also protected as I see where I am aiming!”

“Maybe so, but what will happen once the plate joints rust?” Müller’s eyebrows are still raised in disbelief.

“Well, what is oil for?”

“And where do you think that will come from? Fiume? Galicia? Hamburg!?”

Alfred open his mouth, only to close it after a second. That’s right. Oil-producing Galicia is gone, and Fiume is still under siege. To mass-produce such ‘bullet-proof’ armour will only mean more strain on German ports, and with Germany now at war…

Müller could already feel the beginnings of a headache. If this gets out, our enemies shall flay us with our embarrassment. [1]

********************

André Barnard, “When the Politicians Fight”; the Diplomatic Dance of the Great War, (Tully Street Press: 2001)

Mention the Patras Pact, and the mind conjures images of sparkling wine and dancing girls, or romantic images of delegates standing in unison, swearing themselves to aid one another in some ancient parable of an ancient Athenian pledge.

But mention its opposite counterpart, and the most colourful scene the mind conjures is that of dour kings and ambassadors hastily scribbling their names on equally dour forms in London.

Post-war nostalgia and the celluloid industry of Italy and the United States are partly to blame for this difference in diplomatic glamour, but said glamour was built on a few kernels of solid truth; the anti-Patras empires didn’t exactly see a bright future on the horizon – especially so for Austria-Hungary and the Ottoman Empire – and the formation of a solid alliance bloc sent these governments scrambling as fast as possible to form a strong counter-bloc. It didn’t exactly help that the weather was uncooperative, with an unusually wet summer darkening the skies of Potsdam and London when the German, Ottoman, Austro-Hungarian, and British delegates finally assembled.

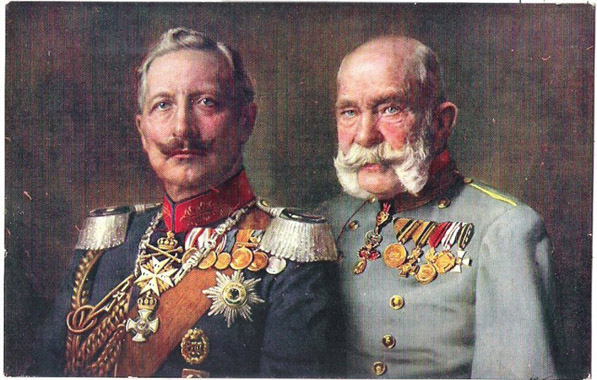

The new alliance between Vienna and Berlin also added to complications. When the Potsdam Agreement was signed on the 16th of May between Kaiser Wilhelm and Franz Joseph [2], it established Germany as the chief benefactor as her ambassadors extracted numerous concessions from their Austro-Hungarian guests. When all the aforementioned empires sent their delegates to London, the Germans expected themselves to be the linchpin and leader of the new anti-Patras alliance. This did not go down well with the British, whom wanted themselves to lead the new bloc instead. As the days rolled on, the halls of Kensington Palace in central London became the scene of heated arguments as British and German ambassadors clashed over war aims, financial loans, and military responsibilities.

In the end, it took the combined forces of the Ottoman and Austro-Hungarian delegates to steer the conversation back to track. On the 12th of June 1906, all four delegations finally agreed to aid each other militarily, economically, and financially against the Patras Pact. In an effort to make their alliance seem better, British Prime Minister Henry Asquith spoke out in a subsequent interview, “We four Powers, thus agreed, have matched the designers of Patras with our own great pact: the Kensington Alliance of the European Continent!”

However, a printing error in the Daily Telegraph capitalized the ‘F’ to create, “We Four Powers”, birthing a new label that is both shorter than the official namesake and glamorously poor when compared to its counterpart. Despite numerous attempts to correct it, the international press (especially in the United States) latched on to the mistake, forever making the ‘Four Powers’ an uninspiring term to denote the British, Germans, Ottomans, and Austro-Hungarians…

********************

Charlie MacDonald, Strange States, Weird Wars, and Bizzare Borders, (weirdworld.postr.com, 2014)

After the Potsdam Agreement of mid-spring, many Viennese politicians expected their new ally to immediately send them fresh troops by the hundreds of thousands to wallop Russia, or to the Carpathian ranges to shore up the Dual Monarchy’s lines. So you can just imagine their shock when Germany, in its first acts, decided to act against France first!

And thus was revealed Concession no. 1 of Potsdam: Germany places their own interests above Austria-Hungary’s.

To be sure, the Russian Empire was a serious military threat, but most of those troops were banging the faraway Carpathians all while 2 French divisions camped at the border of German Alsace-Lorraine. Oh, and Paris was determined to get the place back and steamroll into Baden and Württemberg, come hell or high water! So, it did not take atomic science to see where Berlin should set priorities first, and it wasn’t until 6 days later that the first army corps were mobilized in East Prussia and the first regiments travelled to Austria.

And thus was revealed Concession no. 2 of Potsdam: Germany selects how many troops to send.

Because let’s face it, if you have a border that stretches from the Baltic to Silesia, you’ll need as many men you can save. The first ‘shipment’ – if we can say that, of German troops to the Austrian Carpathians only numbered around 10,000 men, which was faaaaaaaaar too low to shore up the mountainous defenses. Despite the haranguing of the Habsburgs and the Viennese Reichstag, there will never be more than 200,000 Imperial German troops serving in Austria-Hungary throughout the Great War.

But in this concession hides a silver lining. Remember the queer panic that struck Germany last year? [3] Some of the disgraced officers and generals (or at least, the ones that survived) quickly found a way to potentially redeem themselves and ran pell-mell to be inducted into the Austro-Hungarian Common Army. Now, to say that they were accepted is… not the right word. In one example: when the former Imperial General of Infantry, Kuno von Moltke, tried to get inducted, he was instead laughed at and was thrown tutus by Austrian officers, “…for the sole purpose of degrading me. To force me to wear them and dance around to their pleasure, at my abasement.” Really, his journals were a horror show of how he – and his fellow disgraced army men – were treated by their new superiors.

But, queerness aside, their experience and intelligence was of more worth than anything Austria-Hungary had, and quite a few of them managed to shake off their harassment and reclaim their dignity – whether undeservingly or unintentionally lost – under the Habsburg flag.

Kuno von Moltke: “To those whom have spat and hurled at me, I have lived. And oh, how I lived.”

Maybe it was this, among other factors, that helped Austria to regain parts of Galicia.

Besides men, there was also the question of supplies and cash. Since I’m not too good with material goods, I’ll handle the cash first. Austro-Hungarian finances in 1906 were, to put it mildly, a hot mess. Their military budget had transfigured into a monster that swallowed imperial finances and government loans to churn out stinking piles of debt. Public finances were already being cannibalized as the Beer Consumption tax of that April showed (and the wild reactions to it. Seriously, look it up). Still, it wasn’t enough.

And thus was revealed Concession no. 3 of Potsdam: Germany holds the purse strings on their loans.

Despite pleas for a ‘Blank Check’ agreement, no one less than Kaiser Wilhelm himself put his foot down. Rumor has it that he lambasted several diplomats for even proposing such an idea, shouting at one point, “You want me to pay for their failures?!”. Thank goodness then that the German Chancellor was more conciliatory. Eventually, the final proposal did allow for some war funding for the Habsburgs, but with a sting: loans of several hundred thousand Goldmarks shall be granted to Vienna and Budapest, but set at eye-watering interest rates to be paid after the end of fighting.

In an ironic way, it would be these high-interest rates set by the Berlin Reichsbank that would prove more consequential to Austria-Hungary’s long-term survival, more so than cold machinery or hot ammunition…

********************

Issac McNamara, The Great War: An Overview, (Cambridge University Press; 1999)

…Undoubtedly, the grimmest depictions of the Great War in Western Europe came from the Franco-German border.

The buildup of troops on both sides meant that the resulting carnage was nothing short of catastrophic for the border region, with clashes breaking out before the ink in Potsdam was barely dry. With machine guns and mass-shelling a grievous impediment, trenches and foxholes were quickly dug by the combatants to protect themselves, thus creating the iconic wretchedness of trench life. Privation, disease, and the overhanging dread of death stalked the mud walls and bare rooms, where shell-shocked boys went so far as to injure themselves to escape active service. Conditions were no less alleviated by the gigantic rats that knawed-off anything edible they could find, human or otherwise.

It is no wonder then that the ‘veterans literature’ that sprouted afterwards saw the misery of the trenches as synonymous with hell.

And for all their sacrifices, the prize of Alsace-Lorraine became a divided land. By mid-July, French and German forces occupied around 50% of the border region, and the ratio would remain so for the rest of 1906. Successful offensives became rarer and more of a fantasy with contemporary capabilities, though the German high command tried several night offensives that only resulted in wayward soldiers stumbling on ruined earth in the dark into enemy hands. By early autumn, desperate pleas were made by both sides to the Low Countries to open their borders, while a race was on to find ways of circumnavigating trench defences.

In the east, the carnage was no less brutal, yet the offensives were far more mobile. After the success of pushing back Austria-Hungary to the Carpathians, major sections of the imperial Russian army quickly swung north to take Königsberg and Danzig, only to be met from behind by a wall of German infantry and artillery whom catapulted themselves from Pozen and Silesia. The Russian advance was further slowed down by volunteer battalions which mushroomed all across eastern Germany, picking off stray units and supplies. The opposing forces reached their culmination in the battles of Bromberg and the Masurian Lakes, which saw over 400,000 men on both sides engaging in offensives and counter-offensives throughout the summer of 1906.

Though the Russian army had accomplished itself greatly in the Great War till then, her generals quickly realized the mistake they had made. Powerful in manpower though their forces may be, the addition of the German Empire as an Austro-Hungarian ally added over 900 kilometres of new borders to patrol. Furthermore, a series of miscalculations by Russian generals saw catastrophic losses for them by the autumn, resulting in German forces expelling Russian ones completely from the German Empire by early November. However, each land gained came at a cost of German lives which rose so high, the newspapers of Berlin stopped reporting casualty numbers in the east by Christmas.

Such losses were further compounded by the turmoil of the Carpathian theatre. The addition of German troops and disgraced ‘queer’ officers into Austro-Hungarian alpine defences did little, at first. But as the battles of the German north soaked up available men and supplies, and as the qualitative nature of the defenders increased, the scales began to tip. In mid-September, Austro-Hungarian forces in partnership with pro-Habsburg Polish partisans began to advance piecemeal down the mountains, aided by Russian disarray over the battles of eastern Prussia. By December 7th 1906, the advance was serious enough that the Russian imperial command grew wary of an entrapment by the German north and the Austrian south, and thus ordered a slow ‘fighting withdrawal’ of troops to the Vistula River.

Nearly 100,000 Russian soldiers shall be prisoners of war by the end of 1906. The combined German and Austro-Hungarian losses were almost as high.

The Balkans also saw some changes after Germany’s involvement, though the effects would be delayed until late autumn. German aid and the costly victories in the north provided enough material relief for the Honvéd in their advance into Serbia, though Belgrade still eluded capture as 1907 dawned. More consequentially, the Hungarian threat forced the Serbian government to withdraw several divisions from Ottoman Bosnia and Rumelia, allowing Ottoman forces to strike some important victories against Serbian forces and local partisans. Perhaps the only places where Germany’s involvement meant little was in the Alps and the Adriatic basin, where Italian forces still held Fiume under siege while Albania, Dalmatia, and parts of Bosnia remained in their palm…

…In naval matters, the inclusion of Germany was the miracle of God the British needed. After being hounded and chased across the globe by flighty French and Italian gunboats, and after months of holding back to defend the British Isles and transatlantic shipping routes, the arrival of the Kaiserliche Marine seemed miraculous. After the Four Powers conference, German battleships quickly aided the Royal Navy in blockading the northern French coast and interdict the Baltic sea from Russian forces and shipping. In the Atlantic, their assistence was essential in safeguarding naval convoys travelling from Canada, whose ecomony grew bigger and bigger from supplying the British Empire and her allies in their time of need. The British and German colonies of West Africa also benefitted from more relievement, though it also led to a nasty spate of hit-and-run attacks by the disgruntled French navy on docked vessels.

And the German Empire’s involvement could not come too soon. The split priorities of the Royal Navy generated an opportunity for unaffiliated nations to seize British possessions, some of which was acted upon. Most infamous of this was the short occupation of the Falkland Islands in the summer of 1906. On May 29th, the Argentine Republic led an invasion force of 900 men to seize the windswept lands to “complete the formation of the nation”, as the then-President José Pérez Uriburu [4] proclaimed. Fuelled by reports from French spies and diplomats, he banked on the Royal Navy being too overextended to force a counterattack, which backfired spectacularly when a combined Anglo-German naval force pummelled the minuscule Argentine navy to the seafloor the very next month, retaking the islands.

The Argentines scrambled to draft a peace treaty before the guns even cooled.

Another, more subtle, effect of German involvement was the opening of naval ports by her fellow allies to the German navy and merchant marine. While this was considered standard procedure, it would mark the dawn of a new commercial power to rival the British, albeit not without some odd occurrences…

********************

Outskirts of Kuching, Kingdom of Sarawak, 25th September 1906

Outskirts of Kuching, Kingdom of Sarawak, 25th September 1906

Karl knew the rulings, but he couldn’t help his eyes wandering around.

It was just so… different. Everything is so different, especially over the last months. From the stormy tides of the Atlantic and the Argentines, to around the tip of Africa, then up into Madagascar and India of which he had only seen in pictures, he could never imagined his choice to enlist in the navy could lead this far.

And now I’m here, in the land of the White Rajahs.

As his fellow men marched in formation, following behind the captain and the two ladies – whom were undoubtedly of the storied Brooke family, Karl let his eyes glance a second or two at the crowd beside the road. The nearby locals had crammed themselves to and fro to better view the German newcomers, fresh on shore leave after an arduous journey chasing French and Italian ships across the Indian Ocean. The ports of India were colourful enough, but the sights and sounds of Kuching were simply too much for him to just keep his gaze still.

Thank God I’m not the only one, though. Despite the official formation, Karl could see his fellow sailors peering this way and that in quick glances. Though the tropical climate was as hot and mucky as the naturalists’ said, Kuching’s farms and shophouses were a world onto their own, with bamboo bridges soaring over streams paddled with cockerels and longboats. On the street, porcelain and lacquerware sellers from China and Japan haggled with local men and women wearing cloth caps and delicate head-veils. Small Indian children peered around their elders’ legs to look at Karl’s procession, and – to his inward delight – around everywhere were the bare-chested and noticeable forest-folk of Borneo, with simple styles and inked skin that wrapped from the knees up to their very fingertips.

Karl wondered if they have a special meaning.

As with many adventurous boys, Karl had grown up hearing the fantastical tales of the family that founded the Sarawakian adventurer-state. In the cheap prints and serial stories he and others read back home, the Brookes were men whom wrestled with tigers, fought with head-hunters, and danced with native girls with flowers in their hair. Nowadays, he knew they were exaggerations, but seeing them with his own eyes brought a clarity to Karl’s mind. A strange mix of fascination and curiosity.

I want to hear your stories.

“Halt!”

The group stopped. They had arrived before what seemed like a half-completed pillar, bedecked in scaffolding and the surface seemingly etched with swirls and whorls that Karl guessed were native motifs. With a simple solemnity, the two ladies – the widowed dowager and the princess royal – explained the structure’s nature to the captain, and what little English Karl learned was enough for him to discern their meaning. A memorial to their dead? But don’t these people hang their heads from their homes? Unless… this is for their unknown dead, whom they couldn’t find? [5]

Standing still before the unfinished pillar. Karl was struck by how much Sarawak had suffered for its actions.

Now moving away, he heard a few more snippets of his captain’s conversation with the Brooke ladies. As the words, “shell shock,” and “Rajah,” were said to the women’s astonished faces, a thought struck his mind.

Where is the new Rajah anyway?

********************

Notes:

First, happy new year everyone. Second, yes I know the oath-painting technically depicts Romans in salute, not Greeks. But when you’re trying to evoke some romantic notion of a fictional alliance, that’s probably the most famous painting there is of such a thing. Third (and yes, this is an edit), the monument is IOTL the Heroes Monument of Kuching.

[1] Oh yes, these types of body armor really did exist and were used in some fashion during WWI in real-life! The exact model that is being worn in the picture, however, was more built for research purposes and it is unclear whether the above armor was actually mass-produced during the war.

[2] See the previous post for more info.

[3] See this post for more info on the queer panic Germany endured.

[4] The ITTL familial relative of José Evaristo Uriburu (the Argentine president who participated as arbiter in the peace conference of the War of the Pacific) and José Félix Uriburu (the Lieutenant General whom overthrew the Argentine government in a coup during the Great Depression). Needless to say, the family is just as (divergently) political here.

[5] Ahh ignorance, how do I not miss you. For the record, Dayak tribes across Borneo differ very greatly in funeral rites and in paying respect to the dead. The Bidayuh – depending on the tribe, time, and place – would either cremate their dead, bury them, or simply abandon them in the forest with minimal ceremony. The Iban mostly opt for burying their dead in shallow graves, though a number of Iban tribes also build a funerary structure called a sungkup on the grave to represent the longhouse in the afterworld. The Punan Bah of Bintulu and the Upper Rajang erect funerary columns from tree trunks to store their chief’s bodies within, while the Kadazan-Dusun of Sabah have a myriad of funerary practices that include all the above, although some tribes also opt to store their dead in caves.

Last edited: