‘Abdurrahman Khan’, War and Peace in Colonial Borneo (Kenyalang Publishing; 1985)

It could be said that the 1850s was a time of great change for the Kingdom of Sarawak, not just in terms of general development, but in wars and peace as well. From 1853 to 1862 the nation underwent not one, but two simultaneous rebellions along with an uprising that threatened to unravel everything that James Brooke and his allies created. Along with changing the way the Brooke kingdom waged war, the upheavals of the 1850s would also change the way the Dayaks were treated by their overlords, leading to the modern state that exists today.

The first, and most famous, of the 1850s upheavals was the Rentap Rebellion which rocked the new Simanggang Division and reevaluated Brooke policy toward the Sarawak Dayaks. The rebellion is named so after the Iban chieftain that headed it, Libau Rentap. He was born in the early 1800s and became one of the leading Manok Sabong – fighting men – of his tribe during his youth, leading war expeditions deep into Dutch Borneo. Over the years, his martial prowess and tribal warring earned him great respect among the Ibans of Batang Lupar and the surrounding rivers, resulting in the man being appointed chief of his tribe upon his predecessor’s death.

As the Rajah James Brooke began expanding his powers deep into Sarawak, the English adventurer’s policies soon began to conflict with the ways of the Iban. The British Royal Navy was combating piracy up and down the Bornean coast, branding the warring Dayak subgroup as ‘pirates’, a term that rankled Rentap who saw the labeling as undeserved. Then there was the decision to build forts up and down the rivers to patrol the movement of the Sarawak Dayaks, a move that infuriated Rentap as now the tradition of war expeditions became all but impossible. The final straw was the ban on headhunting enacted by the White Rajah, whom the Iban saw as an affront to their faith and their way of life. Even with the relaxation of the rule by James, the chieftain had made up his mind. He gathered his forces, sent word to his allied tribes, and planned for war.

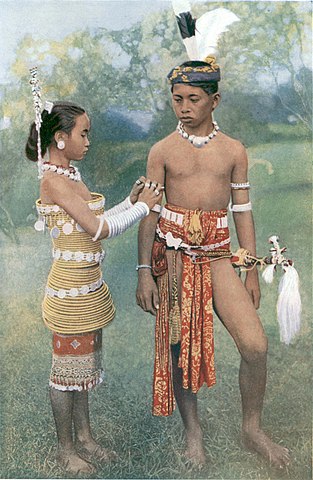

A possible sketch of Libau “world-shaker” Rentap. There are no photographs of him and what physical features he has is distorted due to native aggrandizement. This is the closest we will ever get to the enigmatic chieftain.

Libau Rentap had fought against James Brooke and his allies before the 1850s, but it was during the decade that truly defined the war for the Simanggang Division. In March 1853, the chieftain assembled a group of warriors and tried to attack Fort James. The attack, though unsuccessful, did result in the death of a British officer, a move that shocked the new administration in Kuching. In response, James traveled to Bandar Brunei and appealed before the sultan for annexation of the area, as well as heading an anti-headhunting expedition up the Batang Lupar River in June. His expedition was a failure as much as Libau Rentap’s had, though considering his explorations into Sentarum and claiming it for Sarawak, it could also be said as an unexpected success (an amused Charles Brooke would later write of this as “…searching for sharks and catching gold”).

Undaunted, James launched expeditions on the surrounding rivers to catch the wily chieftain, eventually battling with him on the Battle of the Lang River in 1854, of which Rentap lost. The chieftain and his followers retreated upriver to Mount Sadok and built a strong fort with extra walls and fortifications to hamper off any British assault. From this base, Rentap would launch raid after raid upon the forts of Simanggang and any Iban village that sided with the Brookes, leading to the area being in a perpetual state of unrest up until 1861. Rentap also gathered allied chieftains from other communities to his side to join the fight, confounding the Brooke’s efforts by conducting surprise raids from various rivers in the Division.

It was also around this time that another leader decided on rebelling against the new and rising power in Kuching. This time, it was a Bruneian lord by the name of Sharif Masahor, a man of Hardrami and Melanau roots and rumored to be a descendent of the Prophet Muhammad. From his base in the town of Sarikei, Masahor viewed the upstart Kingdom of Sarawak with wariness and suspicion; he was rankled by James’ rising influence around Brunei and in the Rajang River basin, especially with the building of fort Emma in Kanowit, an area that was supposed to be outside the Kingdom of Sarawak’s jurisdiction. As with Libau Rentap, Masahor gathered his forces and sent word to his allies of his plans – with the exception that he was influential enough to bring not just the coastal Malays to his side, but native Iban and Melanau tribes as well.

A romantic sketch of Sharif Masahor. Note the cannon that lay beside his feet; ordinary lords do not stand that close to such a weapon.

Taking advantage of the White Rajah’s emergency departure to Singapore in 1855 (the English Parliament grew wary of the English adventurer’s actions in Borneo and wanted to question James on his behavior), Masahor rallied a force of 150 Perahus and launched attacks on Fort Emma and the Brooke-allied towns of Maling, Mukah, Oya and Saratok, causing the deaths of several more British officers. With the absence of Rajah James, Masahor quickly took control of the Rajang Delta and expelled any remaining Bruneian lords that sided with the White Rajah, forcing many of them to flee to safety in Sarawak. The Bruneian lord also began conspiring with other like-minded men to launch an attack on Kuching village, wanting to oust the White Rajahs from Borneo for good.

Surprisingly, the one man who arguably started it all – Pangiran Indera Mahkota – did not want to get involved in the rebellions and related affairs, either for Rentap or for Masahor. Ever since the English adventurer took the position of Governor in Kuching back in 1842, the Bruneian noble has led a drastically unassuming life in Bandar Brunei, composing poetry and advising senior ministers on state affairs. Contemporary accounts from both the court and the Royal Navy described the former lord of Kuching as an old man, humbled by his life and his experiences throughout it. After the formation of the Kingdom of Sarawak, several Bruneian lords rallied around the nobleman as a symbol of the oppressing British, but soon abandoned him once he proved to be nothing more than a lame duck.

The Bruneian lord’s poems (here published under his alternate title: Pangiran Shahbandar) are still studied by Sarawakian and Bruneian schoolchildren today, even the verses that are anti-British in character.

The last and most surprising of all the upheavals was the Kuching Uprising of 1857. The Chinese minority in Sarawak had a tumultuous start, beginning with the exodus of Chinese miners from Dutch Borneo in 1851 as a result of inter-clan warfare. These miners soon found themselves under the employ of the Kingdom of Sarawak, mining the antimony and gold deposits underneath the mountains of Bau and Lundu. However, the mining communities soon began assembling among themselves, forming secret societies and trading opium illegally from the nearby Sambas Sultanate and the port of Singapore.

In the mid-1850s, the Kuching government finally began discussion on raising taxes among certain goods and managing the flow of illegal opium trade coming from Dutch Borneo. This rankled the Chinese mining communities for the supposed ‘intrusion’ on their rights and immediately began agitating among each other for an uprising against the White Rajah. Boats and sampans were kept away from prying eyes while several Royal Navy officers reported having their rifles stolen. The apocryphal announcement of the Chinese Commissioner in Canton in 1856 of paying thirty Dollars for the head of an Englishman certainly aided to the cause. Despite all of this, the rebellions in Simanggang and the Rajang Delta kept Rajah James and his cousin Charles looking elsewhere while the miniscule European community in the capital thought of such an event as simply implausible.

At 12:00 midnight on February the 26th 1857, the Chinese made their move. Groups of miners traveled down the Sarawak River under the darkness and attacked several small forts upriver from Kuching, overpowering the guards and setting the structures ablaze before reaching the capital. Rajah James was forced to flee from his residence while the small European community fled to take shelter in a missionary school, watching the capital burn up in flames. The Chinese were surprisingly cordial to the foreign men and women, allowing all but a few government ministers to leave Kuching by the next morning; partly due to the understanding of what will happen if European women and children got harmed in a foreign uprising.

A drawing made by a missionary showing the wives of British officers looking in horror at the burning bungalow of Rajah James.

At the same time, Charles Brooke was heading back to the capital from Simanggang on his war-boat along with a thousand Brooke-allied Dayak warriors, unaware of what has happened. By the evening though, the younger Brooke and his allies found themselves battling with the miners, expelling them from Kuching and ending the Uprising no less than 48 hours after it began. The following weeks saw a brutal crackdown on Chinese secret societies and clamping of the illegal opium trade, much to the consternation of Batavia as Chinese criminals streamed their way across the border into the Sambas Sultanate, causing more than a few disturbances once they arrived.

The rest of the 1850’s was devoted to rebuilding Kuching, re-establishing public order and combating the rebellions of Rentap and Sharif Masahor. The Brookes used every available contact they had to secure weapons and goods for their kingdom; gun-boats from the Royal Navy, supplies from their enthusiasts in England; a large loan by Baroness Burdett-Courts; and so on. Brooke-allied Dayaks were also used as additional troops, swayed by the Rajah’s Semangat and the promise of plunder and enemy heads (the headhunting ban was waived in times of battle). Rajah James also bit the bullet and requested to London of his kingdom becoming a protectorate of the British, though with the Indian Rebellion of ’57 diverting the attention of Parliament, his requests were rejected and – in an idiotic move – the Kingdom of Sarawak’s status of independence was shunted aside.

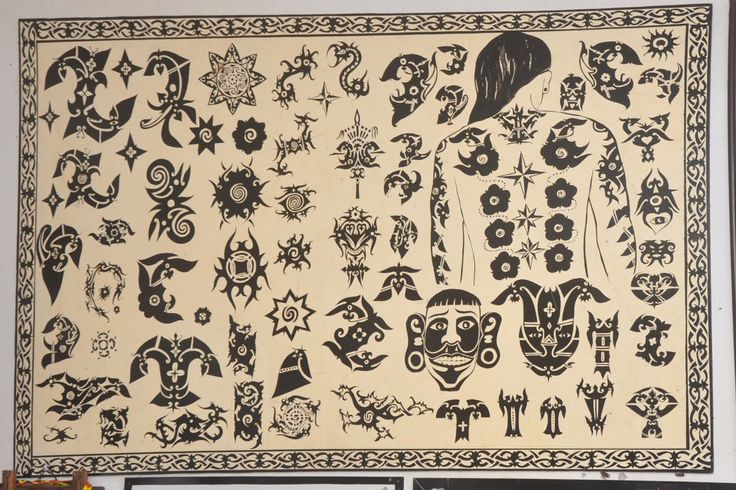

A drawing by a British officer, showing Brooke-allied Dayaks using blowpipes against a Masahor-allied war fleet.

Libau Rentap would be the first to fall. After a series of battles against the Dayak chieftain, James Brooke personally led an attack on Rentap’s base fort on Mount Sadok in 1861. During the attack, the Iban chieftain’s gunpowder stores for his cannons caught fire and exploded, killing the man in a fiery blaze. As for Masahor, his status as the lord of Sarikei was revoked by the Bruniean Sultan and he was eventually captured at Mukah before being deported to British Malaya. James Brooke also annexed the entire Rajang River and its headwaters from Brunei, wanting to prevent another large-scale incident from ever happening again.

And thus, the fledgling Kingdom of Sarawak survived through the most tumultuous decade of its entire history. Not only did it survived against two major rebellions and a successful short-lived uprising, it also survived against British public opinion, the disinterest of Parliament and denial by Britain of being an independent state. There would still be Dayak uprisings long after the era, but none would be as big or as far-reaching as those of the 1850’s…

An anachronistic map of Sarawak during the hights of the two rebellions and the Kuching Uprising, circa 1857

__________

Footnotes:

1) Both

Libau Rentap and

Sharif Masahor were actual figures that did rebel against Brooke rule, and in their rebellion’s peak controlled large parts of Sarawak and Brunei.

2) The Chinese Uprising was an actual uprising that occurred in 1857 due to an increase in taxation and the clamping of the illegal opium trade.

3) The Brooke government had several gunboats in their possession in OTL, some loaned from the British Navy while others coming from (spoilers!)

4) Other than changing the dates of the events, some of the details of the battles (most notably Rentap’s death ITTL) and the arrival of the Chinese in Sarawak, almost everything about the 1850’s were OTL.

5) Pangiran Indera Mahkota really did compose poems in his life; most notably the

Syair Rakis, which talks about the dangers of accepting foreign rule.

![ESr5kKH.png]](/forum/proxy.php?image=http%3A%2F%2Fimgur.com%2FESr5kKH.png%5D&hash=52064b2ffa9bb660be7ca4f41d7d9026)