Mate... this isn't AP English. We aren't going to judge you for misplaced sources here. Or at least I won't.It has occurred to me that I've made a terrible mistake in the course of writing this timeline.

In my conversations regarding the planning of this timeline, I've always gratefully acknowledged the sources created by David Portree at his Spaceflight History Blog. David's research of unflown NASA missions has been both impeccable and invaluable in my writing. I have acknowledged this in my private communications with David, but I recently realized I had not publicly made this as clear as I'd wished to. David's work was especially useful in researching the details that went into the flights of Apollo 14 and Apollo 15.

Additionally, this work would not have been possible without the excellent articles by Paul Drye in his False Steps Blog. His articles on the MOLEM concepts were vital to the latest entry in this timeline.

I also had the honor and privilege of speaking with Sy Liebergot during my initial planning of this timeline. He spoke with me via Skype for nearly 2 hours and his insights and stories were the highlight of my 2017. I would encourage all of you to read his book. The details therein helped me greatly in writing the saga of Apollo 13.

While I have acknowledged all of these sources in various places throughout my postings on this forum, I wanted to be very clear in my acknowledgment of them before going any further. Please understand that my error was one of negligence, not malice. I apologize to these men and to my readers for any offense this may have caused. I will try to be more direct in citing source materials in further posts.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Ocean of Storms: A Timeline of A Scientific America

- Thread starter BowOfOrion

- Start date

BowOfOrion, your scruples do you honor. Thanks for the additional information regarding your sources, and keep up the excellent work. It's a privilege to read you.

XVI: The Great Unknown

The Great Unknown

1 January 1972

Apollo 16

MET: 260:12:27

Marius Hills

Callsign: Beagle

“The extent and magnitude of the system of canyons is astounding. The plateau is cut into shreds by these gigantic chasms, and resembles a vast ruin. Belts of country miles in width have been swept away, leaving only isolated mountains standing in the gap.” - Joseph Christmas Ives – Report Upon the Colorado River of the West, Explored in 1857 & 1858

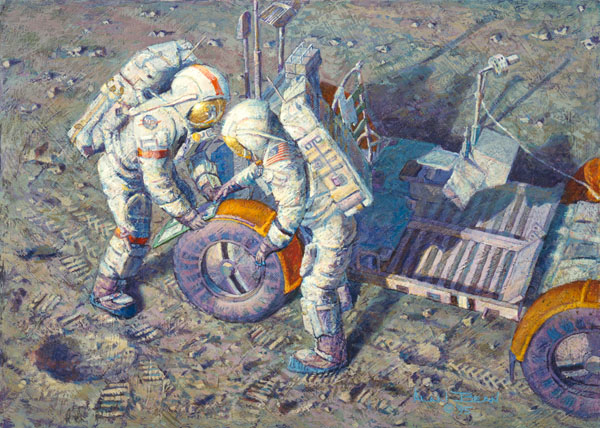

The first priority for the EVA was checking the brakes. At this point, it was routine, but today it had a special significance.

Scott knew it was more superstition than precaution that made him do it; but no one that he knew had ever died from being too careful. After Beagle’s brakes had been double-checked, he found four relatively large rocks scattered near the rim of the skylight and wedged them in front of each wheel. Chocks to ensure that his anchor wouldn’t be shifting during his descent into the unknown.

As Keller finished with the wheels, he looked over at the rim. John Young was already there, assembling the spool mount. He followed the steel cable from the front of the Beagle over to where John was working. He stopped a few feet from the edge of the hole and stared into the abyss for a long moment.

Officially, he wasn’t nervous. Nerves were for lesser men. Men who hadn’t risen through the Naval Academy, hadn’t landed on a tossing aircraft carrier deck at night, hadn’t ridden the largest rocket built by mankind to a world a quarter of a million miles away. Certainly men such as this wouldn’t be afraid of the dark.

Unofficially, the dark was the worst of it. He stood at the precipice of this pit and could not see the bottom, and, like any man who had walked on the Earth or the Moon, he feared what he did not know.

The crackle that accompanied John’s voice over the radio brought him out of his contemplation.

“All set back there?” asked John, turning to take another look at the MOLEM. Even with the world watching back on Earth, they felt comfortable enough to be casual in their tone as they started the day.

“Yeah, just wanted to give the brakes some help.”

“It’s a good idea. I was gonna mention it if you hadn’t.”

“Yeah. You’re good here? Checklist has me getting the low-SEP ready.”

“Yeah, I’m fine. Go ahead.”

Keller walked over to the Subsurface Experiment Package, or “Low-SEP”. Low-SEP wasn’t much different from the standard ALSEP packages that had been left at the other landing sites, including three miles from here where he and John had landed in Adventure a few days ago. The biggest difference was in what the package would look for and how it would communicate with Earth.

Low-SEP would be lowered into the pit first. Once Keller reached it, he would activate the package and a data cable would be winched down to him. The small antennae left at the rim of the hole would relay the findings back to Earth. The biggest question Low-SEP had to answer was with regards to the latent levels of radiation in the hole. If the underground cavern had a significantly lower level of cosmic rays, then this collapsed lava tube, and others like it scattered randomly around the Moon, could possibly become ideal sites for the first permanent lunar outposts.

Scott Keller ran a quick diagnostic of the experiment package. Houston confirmed the incoming data, then he shut down the experiments and carried the box to the rim of the pit.

The pit had been discovered during the analysis of the photography from Apollo 14. This was one of four that had been found in various spots on the Moon. There were likely to be others that were simply not as prominent. The most likely hypothesis was that this pit was the collapsed ceiling of a lava tube where magma had flowed millions of years ago. This was the consensus of every geologist in NASA’s employ back on Earth.

But where was the fun in that?

To the uneducated masses back on Earth, the pit had been a potential source for all manner of science-fiction wonder and mischief. After all, this was a big, dark hole on the moon. It had a diameter of more than 50 meters and was nearly as deep. In the eyes of the public (and a few opportunistic sci-fi writers) that was certainly large enough to hold a pyramid, or an alien spacecraft, or the remnants of a lunar civilization, or spider-women from Mars…

Surely it had to have something more interesting inside than the super-cooled remnants of lunar magma.

Keller cracked a smile as they lowered the Low-SEP into the hole. He had enough confidence in the relative simplicity of the universe that he wasn’t worried about encountering anything dangerous, or even alive at the bottom of this hole. Still, it was a challenge not to think about some of the more grizzly possibilities. After all, he was only the tenth man to walk on this world. There was so much that they didn’t know. And it was so dark down there.

Twenty minutes later, Keller and Young both eagerly leaned over the lip of the pit as the Low-SEP deployed its most important feature.

Attached to the top of the equipment was a telescoping rod, 3 meters tall at its full length. At the top of the rod was a hardened light fixture, lovingly called “the lamppost” that would provide illumination to Scott Keller during his exploration of the pit.

As they peered into the hole, lit for the first time ever, Young asked his LMP, “What was your bet again?”

“I had 50 bucks on a UFO.” Keller replied.

“Right, I said 4-armed monster that eats humans. Jack had the race of green-skinned girls from Star Trek.”

“Well, what do you expect from a bachelor?”

Young laughed, “The thing is, if we find one, he’s gonna insist we bring her back with us.”

“Sarah told me if that’s the case, Jack has dibs.”

They laughed as they stared down into the abyss.

“Okay, Houston, just seeing rocks so far. Looks like a good scattering of boulders. Low-SEP is sitting on a relatively clear point. I think it’ll be fine if we put Scott down right next to it.”

Elliott See was CAPCOM for today. His voice came through 5 by 5. “Roger, copy Beagle. We’d like you to get a couple of panoramic shots on the camera so we can take a look before giving the go.”

“Copy, Houston. Here we go.”

Young tilted the lens down and did a few sweeping pans. The live audience, significantly increased from the numbers that had watched Apollo 15, got their first look into the hole.

Broken boulders and the same tepid gray that had marked the rest of lunar explorations. No grand structures. No great skeleton. No alien monolith. Just a dry pit of rock, older than human civilization.

Thirty minutes later, after the harness had been checked four times, John Young took his suit radio off VOX. Keller saw his movements and did the same.

“Scott…”

“It’s fine. I’m ready. There’s not going to be a problem. I trust the rig and I trust you.”

“I just wanted to give you a chance to…”

Keller shook his head under his space helmet, then felt ridiculous for doing so, “John, if the worst happens, take me off relay and finish the work. If I don’t come back, I’ve got no regrets.”

Young smiled tightly and felt the same ridiculousness, knowing his visor made the expression moot, “I still say we should’ve sent Jack.”

Keller gave a good laugh and turned his radio back to voice-activated transmissions, “Okay, Houston. My feet are on the rim now. Winch is ready and we’re good to go.”

“Copy that, Scott. You are go for powered descent.”

Scott Keller, father, husband, naval aviator, leaned over the rim of the Marius pit and began his descent into the grand unknown.

As he descended, he tried to describe the striations and layering that he saw in the pit walls. It was quickly apparent that this was indeed a lava tube with a collapsed ceiling. About 10 meters from the rim, the hole expanded in two opposite directions. He could see a gentle curve in the wall that eventually blocked his line of site. The winch cable did not twist or rotate, so he could only assume that a similar site was directly behind him. When he reached the bottom, his first task was to take a series of photo and video that would show as much of this new terrain as possible.

About 10 feet from the bottom, Keller was relieved to find that his fears were subsiding. The lamppost was performing wonderfully and he felt no fear as his feet reached the floor of the pit. Mankind had managed to do what the sun never would, illuminate the deep recesses of this lava tube and look upon rocks that had never been exposed to light.

With all the joy of Columbus, the Wright Brothers, and Frank Borman, Scott Keller began the first of 5 hours of activities in this vast lunar sinkhole. The first order of the day was connecting a cable to allow for the data to be relayed from the Low-SEP to an antenna left on the surface near Beagle’s parking spot.

Soon, his explorations found him climbing up a pair of tilted, broken off sections of collapsed rock. He proceeded more than 200 yards down the lava tube, until the line-of-sight with John Young was broken and he had to turn back. The exploration of this area made him feel like an ant in a subway tunnel, but he could not deny the grandeur of this palace of geologic majesty.

With an hour remaining in his PLSS backpack’s oxygen supply, he was commanded by Houston and John to return to his drop-off point so that he could be raised from the floor of the pit. During his return walk, a stroll of about 50 meters from one side of the pit to the other, he finally confronted the unspoken possibility that he and John had acknowledged before.

The Apollo program had served as a great reminder, for those who were paying attention, of the limitless fallibility of human engineering. Despite the great accomplishments of the program and the men and women who made it possible, there were many situations where the creations of mankind had been less than cooperative during the forays into this new territory.

Scott Keller had, perhaps, trusted human engineering more than any other astronaut before him. He had ridden a Saturn V rocket. He had relied on the SPS of the Service Module to bring him into a stable lunar orbit. He had landed in a spindly Lunar Excursion Module and he had made a home out of the MOLEM mobile laboratory. Now, Keller found himself at the bottom of a hole, trusting a winch and cable as his only recourse to bring him out again.

It was completely understood, though never spoken of, that, should the worst happen during this particular exploration, John Young would, with a heartbreaking stiff upper lip, abandon Scott Keller in this sinkhole, to die a coughing death as his oxygen ran out at the end of the PLSS’s reserves. Commander Young was fully capable of driving the Beagle alone, continuing the explorations of this region, and flying the Adventure back to lunar orbit to meet up with Jack Swigert.

There would be no daring rappelling into the hole to retrieve Keller (or his corpse). The mission protocols were absolute in minimizing the risk to the astronaut who did not make the descent. Every astronaut since Gagarin has understood that rescue is a near-unheard of concept in spaceflight. Keller had made his peace with the idea long before he accepted the assignment to lower himself into the pit at Marius Hills.

Samples were raised up to the surface. His equipment bag was next and both operations proceeded without a hitch. With little thought to the matter, Keller secured the cable to his own harness and said a few final words for posterity from the bottom of the pit. With a confident smile, he felt the slack take up the 1/6th of his weight that had anchored him to this world. The winch began pulling him up and mind he began thinking of the tasks left to do before he and John would return to…

Suddenly, just as he’d feared, there was a jolt and Scott Keller’s ascent stopped twenty meters off of the floor of the cave.

As his heart began to pound, Scott heard the voice of John Young over the radio, “Houston, this is Young. I’ve stopped the cable retraction, over.”

Scott Keller felt free enough to be direct, what with his communications with the ground being filtered through his commander, “John, what the hell is going on?”

Young continued, “Houston, I’ve got an eye on the cable. It’s slipping off of the spool. I want to get it realigned before we finish the retraction. I’m afraid if it slips off the roller…” Young let the thought hang unfinished. The implications were terrifying. If the cable slipped it could hit the surface. If it hit the surface, the cable could shear. If it sheared, then Scott Keller would plunge to a cold, painful death a quarter of a million miles from home.

Keller did not hear Houston’s end of the conversation. He was listening intently to Commander Young’s words though.

“Roger that, Houston. We’ll lower Scott down and try again. I think it was just the speed difference from the descent with the equipment versus lowering Scott. Let me rethread the spinner once he’s down and we’ll try again.”

With an edge of panic, Scott felt himself being lowered back to the bottom of the pit. He dutifully cooperated by unhooking the cable from his harness and, like a drowning man watching a life preserver float away, he watched the cable retract much faster than it had pulled him up. He knew that there was still more than 45 minutes of air in his supplies, but for the first time he began to wonder if he would make it out of this hole.

John Young was all business as he rethreaded the steel cable around the winch’s spool. He spoke to Scott as he proceeded through the repair. “It’s fine, I’ve got this. Just need another minute to get it reset.”

With a bravado that is found only in fighter pilots, Keller maintained a nonchalance about his peril, “Sure, no problem. Just whenever you’re ready up there.”

“I don’t think we’ll need the backup, or to use Beagle as a tow. I see the trouble.”

In the event of a failure in the winch system, the mission plans called for Young to unpack and assemble a backup that had been brought along on the Beagle. If, bizarrely, that system failed as well, the protocol was to board the Beagle and drive (slowly) away from the hole, thus pulling LMP Keller out of the pit with the MOLEM’s drivetrain, rather than the winch motor.

After a delay of only a few minutes, John Young lowered the carabiner down once more and Scott Keller hooked his harness up.

Back on Earth, it was the flight surgeon, of all people, who was the first to know that Keller had completed his ascent out of the sinkhole. The telemetry from the biomonitors on Keller’s skin had informed the surgeon that the line of sight between Keller and the Beagle had been restored. On the monitor at the front of the MOCR and in the homes of millions of Americans, Keller’s outstretched hand could be seen reaching for, and then finding, the hand of John Young. This “handshake on the moon” became a popular photograph for the year 1972, and even found a place on the cover of Time, bumping potential cover stories about the upcoming New Hampshire primary.

Two hours later, Keller and Young were finishing their evening meal, comfortable and secure inside the MOLEM’s cabin.

Young was the first to ask Keller the question that he would be fielding for years to come, “You think it has the potential to be a base?”

“Sure. We clear out the rocks, it’s pretty nice down there. Betting the rads were lower too. It’ll be a good choice if they go for it.” Despite his words, Keller’s tone was almost somber.

“But…?”

Keller shrugged, “After that fiasco with the winch, they’ll never let anyone else down that hole, or any place like it ever again.”

NASA had scrubbed the second descent into the hole which had been tentatively scheduled for the next day. Keller’s pessimism was understandable, but not infectious.

John Young tried to buck up his LMP, “Oh you never know…”

Keller nodded, “I bet it’d be kinda perfect to set up something more permanent though.”

"The region is, of course, altogether valueless. It can be approached only from the south, and after entering it there is nothing to do but leave. Ours has been the first, and will doubtless be the last, party of whites to visit this profitless locality.” - Joseph Christmas Ives – Report Upon the Colorado River of the West, Explored in 1857 & 1858

Pity he didn't bring a model UFO with him, casually placed near the low-SEP.“I had 50 bucks on a UFO.” Keller replied.

“Right, I said 4-armed monster that eats humans. Jack had the race of green-skinned girls from Star Trek.”

Pity he didn't bring a model UFO with him, casually placed near the low-SEP.

I hate it when my readers are more clever than I am. Wish I'd thought of that!

Impressive! It definitely has suspense and fear mixed in with the wonders of the deep dark pit.

Oh my goodness... @BowOfOrion this is GRIPPING. My stomach was actually in a knot the whole time. I've always wanted to know what's inside those tubes... a small autonomous flying 'puffer', or some sort of rover that could lower itself down... but no, you send an astronaut down there! In 1972! This timeline is simply amazing, both for the content and the quality!

I am glad to see that Elliot See is still around! But, I must ask, who is Scott Keller? I googled and no astronaut by that name came up. Is this simply butterflies? Am I forgetting a mention in an earlier chapter?

I am glad to see that Elliot See is still around! But, I must ask, who is Scott Keller? I googled and no astronaut by that name came up. Is this simply butterflies? Am I forgetting a mention in an earlier chapter?

I am glad to see that Elliot See is still around! But, I must ask, who is Scott Keller? I googled and no astronaut by that name came up. Is this simply butterflies? Am I forgetting a mention in an earlier chapter?

Cobalt, you're always on the case. I'm so glad you asked. Scott Keller is hard to find, but not impossible. I'm not going to spoil your search, but suffice it to say, he's a friend of Jack Crichton's and he's partial to the name Wayfarer.

Part of the fun of playing God is being able to... well... play.

Cobalt, you're always on the case. I'm so glad you asked. Scott Keller is hard to find, but not impossible. I'm not going to spoil your search, but suffice it to say, he's a friend of Jack Crichton's and he's partial to the name Wayfarer.

Part of the fun of playing God is being able to... well... play.

Innnnteresting. Very fun. So, since you have done such a good job (to my understanding) of capturing the personalities of the different astronauts, did you do the same for him?

Well, it's something of a blank slate. I only have about an hour's worth of material to work with. It's not a rigid view of the character either. Things like Jack Crichton and Scott Keller and the various tributes to Arthur C. Clarke are more like easter eggs. There for careful observers like you, but otherwise background noise. I give you a lot of credit for going so far as to ask the question. Keep doing stuff like that.Innnnteresting. Very fun. So, since you have done such a good job (to my understanding) of capturing the personalities of the different astronauts, did you do the same for him?

I pride myself on my detail work. For example, the Apollo 12 patch has stars that correspond to the number of children that each astronaut on the mission had at the time of the flight. It's the little things like that that I try to get right. I feel like if I do that, the rest falls into place.

We clear out the rocks, it’s pretty nice down there.

10,000 years ago, there would have been a pair of guys thinking exactly the same thing about a cave on Earth.

Elliott See was CAPCOM for today. His voice came through 5 by 5. “Roger, copy Beagle. We’d like you to get a couple of panoramic shots on the camera so we can take a look before giving the go.”

Thank you for that! I can see him engaged in an engineering heavy mission. He was a key test pilot for General Electric and had a solid grasp of the technical side. Perhaps the first mission of setting up a moon hab...

BTW, this is extremely well written and engaging. You don't have to have all the numbers and figures to be good. In fact, at times that level of exhaustive detail gets in the way of good ol' fashioned story telling. Keep it up!

XVII: The Ballad of Jim McDivitt

The Ballad of Jim McDivitt

25 March 1972

Apollo 17

Crew: Jim McDivitt, Charlie Duke, Ronald Evans

MET: 137: 52: 24

Callsign: Destiny

No one can stop you now.

That’s what he thought as he watched Kitty Hawk slowly float away from the LEM. He’d done it. He’d managed to climb out of the doghouse and get a seat (a commander’s seat no less!) on a lunar landing mission.

Jim McDivitt had fought in Korea. He’d tangled with Soviet MiGs and been as close to death as he’d cared to come.

But that was nothing compared to fighting NASA’s bureaucracy.

For all of the civilian aspects of NASA, the decision-makers were still largely military men, or former military men. There was an unwritten rule for assigning blame in military situations. If you were in charge, you were to blame. It went wrong and you were there.

He’d been at the helm for Apollo 9. Throttling up Spider to 20% during her test flight, the helium disc had ruptured. It had been an inevitable flaw in the system. It was an engineering issue that had everything to do with Grumman and nothing to do with the astronaut flying the ship.

But it went wrong, and he was there. For a long time afterwards he was no one’s favorite astronaut.

Deke Slayton had offered him a cushy desk assignment, “Manager of Lunar Landing Operations.” The networks had wanted him as a commentator and there was a promotion from the Air Force.

He’d told Deke, no. He had signed up to fly to the Moon. He wasn’t ready to back away from that until he’d done it.

That was almost 3 years ago, but he’d done it.

The hard part was learning to hover. He’d been a fighter pilot in the Air Force. He’d been as good as anyone behind the stick of an F-80 Shooting Star. From the New 9, he’d been one of only 4 to be selected as a commander for his first flight. But none of that was good enough after what happened on 9.

Honestly, it was his own idea. He’d needed a hook to get past Deke and the brass. Something to distinguish him from the other guys on the flight roster. In the hallways of Houston, he’d listened carefully regarding “The Great Budget Windfall of 1970” and had paid attention when one item had quietly been dusted off.

The Lunar Flying Unit, earlier thought to be a ridiculous toy and privately ridiculed by most of the astronaut corps, had found new life as the scientists wanted to explore ways to expand the range of moonwalkers.

The LFU had several variants proposed since the mid 60’s. Each one was different in both capabilities and purpose. The one thing they all had in common was the central concept of lunar flight dynamics. A quad of rocket engines, on a set of legs, with an astronaut or two (and not much else) on top.

The early versions called for 2 small, one-man units to be sent. Presumably a primary and a backup for emergencies. That had quickly died out when no one could decide how a disabled astronaut could be rescued by another in a one-man unit. The sequel allowed for 2 astronauts, but the range was small, only about 10 kilometers. By the time they’d have it up and running, the new MOLEM’s would be able to handle that distance much more safely.

In the end NASA decided to follow their updated philosophy of “anything worth doing is worth doing right” and instead of scrapping the concept all over again, went headlong into the most versatile, ambitious and boldest of the concepts.

The Long Range Flyer was designed to hold both astronauts, (a fact that LMP Charlie Duke was less than excited about) and had a range of around 50 nautical miles. The engineers had sold it as a backup in case of a LEM ascent engine failure. As of yet, no astronaut had successfully simulated a rendezvous with a CSM on orbit in the thing, but there was a $100 prize to the first pilot who could manage it.

To learn how to fly this contraption, Jim McDivitt had decided that he needed to learn how to hover and maneuver and deal with the characteristics involved in flying in any particular direction. To that end, he’d arranged to learn on a Huey.

The LFU had the capabilities of a hummingbird, though it looked about as safe as James Dean’s Porsche. It was basically a rocket pack on four legs. Two tanks on either side, one for hydrazine, one for nitrogen tetroxide and two smaller tanks for the helium. On top of the four tanks was a small platform which housed the thruster quads and a base for the 2 seats. Mission plans called for him to unpack it on the 4th day on the surface. This was going to be fun.

“Houston, Destiny, coming through 10,000 now. I have a sighting on Aries. It looks like a lighthouse down there. Very clear. My thanks to the guys from Grumman.” He smirked at that last sentence. No hard feelings, Tom Kelly. Spider was a good ship, but McDivitt was very thankful they’d gotten the kinks ironed out. He had no complaints about Destiny so far.

Tycho was the kind of landing site you dreamed about. It had just about everything you could want. For starters, it was clearly visible from Earth. The bright rays of the ejecta blanket extended out nearly a thousand miles in some places. He’d had a lot of fun showing it to his four children in the backyard over the last few months.

The central peak rose more than a mile above the basin. Standing at the center, he wouldn’t even be able to see the crater walls which were more than 25 miles away. And those crater walls were even more interesting than the center.

Surveyor VII had put down just north of the rim in ’68 and the geologists had been overjoyed at what looked like formerly molten “lakes” of rock which (so they told him) could be signs of relatively recent volcanic activity. As long as you considered a few million years ago to be recent.

McDivitt was told, when he reached those areas, to look for something called tektites, which were small, gravel-sized rocks that were spat out during a meteor impact. If he found them, it would confirm all manner of theories that the geologists had been working up. Additionally, they wanted he and Charlie to look for something called anorthosite, which was part of the original lunar crust.

Out the window he could see Aries’s beacon lighting up every 2 seconds. The light pulsed with the same calm intensity that he felt in his bloodstream right now. This felt right. Destiny was in a perfect groove and he could see exactly where he was supposed to put her down. They’d picked a lovely little spot about halfway between the rim and the central peak, though at the moment, he could barely see either on the horizon. Once they were on the ground, it would be a simple matter to fly over to both sites.

A few boulders scattered around the site, but he already had the LPD where he wanted it. The terrain was a little more rugged than he’d pictured it. The orbital photos hadn’t quite done it justice.

He was mindful of the decent fuel gauges during the final approach. More so than on other flights, he was determined to spare as much as possible. Ron, up in the Kitty Hawk, had been kind enough to drop them in an orbit that made for as little maneuvering as possible on the descent.

It had gotten easier, less tense since the first landings. The orbital calculations got better with every flight. In the space of only a few years, the various lunar mascons had been mapped and could be accounted for to save delta V. Mankind was, slowly but surely, getting good at going to the moon.

It was strange to think of the landing itself as something of an anticlimax. Frank and Al’s had been so nail-biting only a couple of years ago. With every landing, the procedures had been refined and the engineering had gotten that much more efficient. He had nearly 2 minutes worth of fuel left in Destiny’s tanks when the contact light illuminated.

The boys in public affairs had told him never to sound bored once Destiny had separated from Kitty Hawk. Looking out at the stark black and gray of his home for the next two weeks, he couldn’t summon excitement, so he settled for sheer joy.

“Houston, this is Tycho base. Destiny has landed.”

30 March 1972

Apollo 17

Tycho Crater

MET: 251: 04: 52

He hadn’t realized how fun driving would be.

So much of this particular mission was about flying. Flying to the moon, flying the LFU, flying to the center and the rim of Tycho. He had been so focused on that that he hadn’t taken into account the joy of just driving.

This little buggy was nothing like the big bus that John and Scott had lived in when they explored Marius Hills. This was more of a dune buggy, a sand rail. Just 4 wheels and a flat base. Didn’t even have a roll cage. But it was still driving an open-top on the moon. Bare bones, rear-wheel steering joy.

The thing topped out at about 10 mph, but that hardly mattered. He had a good patch of open ground and this thing handled like a dream.

It had been a good few days of exploration. They’d landed on Saturday. First EVA had been Sunday morning and they’d unfolded the rover from Destiny’s descent stage. It was a drive of only about 500 yards over to Aries and they’d gotten out a bunch of supplies. The LFU components had been laid flat in what looked like a toolbox drawer. They’d unpacked it and assembled it in the suits. That had felt pretty Buck Rogers right there, building a flying machine on the moon. Turning wrenches and loading fuel tanks like a deep space mechanic.

McDivitt was no favorite of the brass these days, but he always seemed to get the fun missions.

Day 2 was the first of the field trips. They’d left Old Glory behind at the LEM and had driven out about a mile, taking samples and photos along the way back. Walkback rules were still in effect for rover operations (though the LFU was a different animal) and so Jim and Charlie moved like a fishing lure, casting themselves out far, and then slowly exploring their way back to Destiny.

Now at the end of Day 5 on the surface, he was excited to get back to the LEM. The close-out crew for Aries had thrown in a couple of steak sandwiches (on tortillas this time to avoid crumbs) and he and Charlie were about to have a very good dinner when they got back to base.

He came around a low dome and saw his ship in the distance. At the crest of the ridge he paused.

“Houston, Tycho Base, we see Destiny now. Should be home in about 5 minutes.”

“Roger, Tycho. We copy you have Destiny in sight.”

He started the rover down the incline.

“In sight” was something of a sliding scale on the moon. With no atmosphere, the eye had crystal clear vision all the way to the horizon. Every glance up at the Earth was a reminder of that. The image of Destiny, with perfect sharpness, was just an indicator of line of sight, not distance. He knew from the odometer that there was easily...

Suddenly the world flipped upside down.

The lack of sound played hell with one’s sense of disaster. On Earth, an event like this would have started with a scraping sound, or even a good taut SNAP that would shatter the time before and after the incident like a lightning bolt.

The moon gave no such fair warning.

Jim felt his stomach lurch sharply and then completely float away as the rover hit the dip. Charlie had it worse, he was on the right side which was where the trouble started. Charlie didn’t even have time to scream before the wheel popped up and, with its suddenly discovered new kinetic energy, the moon buggy barrel rolled onto its back, with two fragile astronauts strapped to its netted seats.

“Oh, God,” McDivitt managed to get out, just before the 1/6th gravity returned the rover to the surface. For the first Roman Catholic on the moon, a prayer, even a clipped one spoken in panic, seemed appropriate for this moment.

The rover skidded to a stop on the Tycho basin. He was alive, so that was a good start. He didn’t feel any pain to speak of, so that was better. The crackle of the radio link to Houston had gone quiet. He also didn’t hear Charlie.

“Charlie? You okay buddy?”

Nothing.

“Houston, Tycho. We’ve had an accident here.”

Nothing.

“Houston, Tycho, do you read?”

Nothing.

He reached his arm over to Charlie’s seat, turning himself to look. His hand found Charlie’s arm. It was solid and he felt much better. He gave his LMP a gentle pat and got one in return. They were both alive.

His hands then moved to the harness that was holding him to the seat.

All he could see through his visor was the lunar surface a few inches above his head. The rover seemed to be totally upside down and he and Charlie were being held by their straps. The high-gain antenna and one of the equipment boxes on the back of the buggy were its only contact with the ground. As he moved to unclip his harness, he felt the whole assembly shudder with his shifting weight.

The fall to the lunar surface was only a foot or so, and in 1/6 gravity was no cause for concern. He crawled out from under the vehicle and then looked back to find Charlie doing the same on the other side.

He walked around the back of the rover and tried to talk to Charlie again. Charlie looked at him and pointed at his ears. He wasn’t hearing anything either.

Okay, this was bad.

He approached Charlie slowly and put his arms on his shoulders. They’d practiced this on the ground back in Arizona, during the field training. He slowly moved his head until their visors were touching.

The gentle tap of the visors was oddly reassuring.

“Charlie, can you hear me?”

Charlie’s voice sounded like talking to someone through a window. “Yeah. 5 by 5. Are you okay?”

“A little shaken up but I’m fine. You?”

“I’m all right. Nothing broken. What the hell happened?”

“I’m not sure. I think we hit something. How’s your O2?”

Charlie broke away from the hug to check his gauges. He quickly resumed the hug and tapped their visors together again.

“It’s falling. I think I’ve sprung a leak.”

McDivitt marveled at the calm in his voice.

“Okay. Not to worry. Let’s see if we can find it. We’ll get you taped up and head back to the LEM.”

“I’m not hearing Houston. Are you?”

“No. I’ve got nothing on the headset.”

“Same here. Why aren’t we hearing them?”

McDivitt broke the hug and took a look around. The high-gain dish was busted. The low-gain antenna on the rover was in pieces and what few pieces remained were pointed into the ground. He looked in the distance to spot the LEM.

He turned back to his LMP and reestablished contact.

“The low-gain is busted. And we can’t see Aries.”

“But we can see the LEM. Shouldn’t the relay have picked up through Destiny?”

McDivitt had to fight the urge to shake his head, “Destiny’s in low-power mode for the surface stay, remember? Aries is handling air-to-ground relay.” For longer surface stays of these K-missions types, the LEM was powered down severely during surface operations to preserve battery life and consumables. The only thing functioning on Destiny right now was the life support and the lights. All non-essential mission functions were Aries’s responsibility now.

“Right. Okay. Can you spot the leak?”

For a moment Charlie separated and the two went through a complicated dance that would have looked odd on Moon or Earth. Jim was the first to spot the trouble and grabbed Charlie’s wrist.

He didn’t bother pulling them together again. His grip on Charlie’s arm was enough to tell Charlie he’d spotted the issue.

McDivitt retrieved the duct tape from the equipment box on the back of the rover. With careful precision, he wrapped Charlie’s left hand with duct tape. He had spotted the tear on the back of the hand, near the wrist. The escaping gas didn’t leave enough of a trail, but he’d managed to see the rip in the fabric all the same.

He pulled Charlie in after the job was done. “Must have been a slow leak. Are you stable now?”

Charlie checked his gauge again, “Affirmative. Thanks for that. I was starting to get worried.”

“You and me both, brother.”

“Good thing it was just a glove.”

“Yeah, we’ve got spares.”

“If we get to Destiny, are we going to be able to talk to Houston?”

“Yeah. Destiny has line of sight on Aries. We’ll be fine.”

“Good. No offense commander, but when it’s just you and me, it’s creepy as hell.”

“I know how you feel.”

“Can we talk to Ron up in Olympus?”

“He’s on farside for another 10 minutes.”

“Damn. Okay. They’re gonna scrub this whole thing, aren’t they?”

“No way. We’ve got reservations for the presidential suite and I’m not going home early.”

Charlie felt a little better from his commander’s resolve. “You okay to walk?”

“Yeah, but we need to buddy up first.”

“Are you sure? It’s not that bad.”

“Mission rules. It’s fine. Turn around.”

Charlie did just that. Jim attached the buddy system hoses between their backpacks. Charlie permitted himself a sigh of relief as he saw his gauge rise a bit. Whatever happened from now on, they’d live or die together.

Jim didn’t bother pulling him in again. Just used the hand signals to say A-OK and then pointed in the direction of Destiny.

The walk took about 20 minutes as they coordinated their bunny hops across the surface. Between the dancing and the hopping, they were quite the sight. It was unfortunate that the rover’s TV camera was aimed squarely at the dirt right now.

McDivitt, with the silence of his isolation and the single-mindedness of the walk back to Destiny, had a moment to consider what was about to happen.

First of all, Houston would be mad as fire. The rover crashing was a nightmare scenario for any mission. He had known before liftoff that he’d never get another flight again, but now he was worried that they’d cut the surface stay short, or at the least not allow him to fly the LFU.

Beyond Houston’s reaction, the wives and kids back home would be pretty well panicked. They’d been out of contact for nearly half an hour now. God knows what anyone back on Earth thought happened. He himself was curious as to the cause of the crash, but he was content to wait until later to figure it out. The whole thing had shook him up and he just wanted to get back inside and reestablish contact with Houston.

About 50 yards out from Destiny, he was able to spot Aries. The cargo ship had been more or less behind the LEM in terms of his line of sight, but he was able to spot her now as the angle improved.

“Houston, this is McDivitt transmitting in the blind. How do you read me now?”

A few seconds later he heard Joe Engle’s voice through his headset. The last time he’d heard Joe sound like this was when the Odyssey’s parachutes had deployed on 13.

“Ohh, we copy you Jim. You’ve given everybody here a pretty big scare. Are you and Charlie okay? Over.”

“Roger, Houston. Charlie and I are both fine. If you’re not hearing him by now then there must have been a failure in his suit radio. We’re on the buddy system right now, sharing air. I’m going to get us back inside Destiny now and we’ll talk this out.”

“Copy that, Jim. What’s your current position?”

“About 20 yards from Destiny and we’re inbound. Charlie’s glove sprang a small leak, but we got him taped up. Once we’re inside and repressurized, we’ll give you the full story.”

“Copy, Jim. We’ll let you do what you need to up there.”

“And Houston, please let the families know we’re safe up here.”

“Roger that, Jim. We’re already on it.”

An hour later, they’d had it out with the ground. No one was happy, but everyone was relieved that Jim and Charlie were okay.

Jim tinkered with Charlie’s suit transmitter while they listened to Houston on Jim’s headset. The volume was up loud enough for them to hear everything in the LEM cockpit.

The original plan had been to test-fly the LFU tomorrow. Just a couple of short hops within walking distance of Destiny and Aries, just to make sure that everything was functioning properly and that Jim had a good handle on flying the LFU.

Obviously that plan had to be pushed back.

The new priority was figuring out what had happened to crash the rover, and whether it could be salvaged to drive again. They’d each told their story a couple of times. As best Jim figured it, they’d hit a rock that hadn’t been overly prominent and they must have been going just fast enough to tip over. Lunar gravity wasn’t always helpful when it came to driving. When all this was over, he planned to go get that rock and bring it home.

Before bed that night, Charlie and he chatted a bit as they laid in their hammocks on Destiny. Charlie finally got around to asking the question he didn’t want to answer.

“Jim… what were you going to say if they scrubbed the rest of it? Told us to pack it in and head home.”

“Well. My mother raised me not to swear. But I figure if there was ever a time and place for being stubborn…”

Charlie laughed, “It’s not like they could really stop us.”

“My thoughts exactly.”

31 March 1972

Apollo 17

Tycho Crater

MET: 266: 18: 23

As it turned out, it wasn’t as simple as he’d been thinking. For starters, there was no rock. He found the divot in the dirt where the small ridge he’d been driving down met the base of Tycho crater. The rover was on its back a few feet away. Charlie and he got their first good look at it since yesterday. He called it in.

“Okay, Houston. Looks like the rover is more or less intact. Wheels are all still on. Frame is still in one piece.”

Charlie was swinging around the other side with his Hasselblad, “Looks like we lost the antennas. Aaand I think we’re down a fender or 2.”

“Ah, God bless it. Remember Arizona? That’s gonna be annoying to fix.”

“Yeah, but we gotta do it, otherwise the dust will get into everything.”

“Right. Okay, Houston, we’re gonna try to flip her back over now. Stand by.”

Charlie took the rear, He found a spot on the front. Flipping her over was child’s play. Here on the moon, the whole thing weighed less than 80 pounds.

Once they had her right side up, he asked Charlie to start dusting her off while he went to inspect the crash site again.

If there were lunar cops in the distant future, roadway accidents would be their easiest cases. The tire tracks from yesterday were perfectly preserved, and would stay that way for the next millennium.

“Okay, Houston. Looks like we hit this divot in the ground at the base of the ridge here. It’s a low impression, but the ground just kind of dips about a foot and a half right here. It might be a small impact crater, ‘cause it’s pretty circular. From the angle where we came in from, it just blends in perfectly with the crater floor. You’d have to be looking from the other side to see it.”

Charlie had come over to take a look. He began with a whistle, “Wow, that’s just bad luck. Just ran out of luck. Nothing for it.”

“Yeah.”

Bruce McCandless was on CAPCOM today, “Okay, fellas. Get some shots of the dip from all sides. Geology wants to have a look when you’re back home. So does engineering. Maybe they can do something for the boys on 18.”

McDivitt felt the unspoken force behind the request. They want us to get shots of this hole so that they know I didn’t just yee-haw this thing into crashing.

Still, it was an order and it was a reasonable one at that. If he was flight director, he’d be ordering the same thing.

For the next few minutes, he and Charlie did their best to photograph the site and preserve it. They were careful not to step too close to the hole.

The guilt returned to him. He’d managed to tamp it down after the accident, but it had come last night after lights out. And it was here again now.

It was a massive relief when the drive motors checked out. Three out of four at least, and that wasn’t bad. Aries had a spare wheel motor on board and it had replacements for the antennae. Spare antennae were light-weight and had been deemed very necessary. They actually had enough to crash this thing twice, not that he planned to. And the low-gains for the rover were the same ones that the LFU used.

They got on board and he drove, very slowly and carefully, past Destiny and another 500 yards over to Aries.

The rest of the morning was a tedious process of finding the right parts, taking off the damaged components and swapping in the new stuff. The fenders were especially annoying since they didn’t have replacements. The best they could do was to clamp a few maps that they weren’t using around the top of the wheel. Jim and Charlie went through a round of suit checks while Houston verified the downstream data from the new antennae relays.

“Do you still have camera control, Houston?”

“Eh… mostly. Looks like we can pan left, but not right. May have to get you to push it around for us sometime. For the moment, we can look straight ahead, which will have to do.”

With everything (mostly) back up and running, they headed back to Destiny to regroup. It was around midday in Houston and they repressurized and had lunch. He wanted to extend this next EVA by a couple of hours, but Houston wouldn’t allow it.

The new plan was to get the LFU situated and ready to go for the next day. The fuel tanks could be loaded. There was a tarp that had to be spread along the ground to prevent the engine from kicking up rocks during the ascent. They’d also need to test-fire the thruster quads along the sides to make sure they were fully functioning.

He felt terrible that they wouldn’t have time to do the first test-flight today. He’d managed to lose almost an entire day’s worth of moon walking. What was that worth? Millions?

He resolved to make the landings at the central peak and the crater rim absolutely perfect to try and make up for the lost time.

It had taken learning to fly a helicopter to get him out of the dog-house last time. He figured the only way he’d ever fly again now is if he and Charlie brought home a unicorn.

2 April 1972

Apollo 17

1800 feet above Tycho Crater

MET: 314: 34: 06

More and more he was fine with never flying in space again. After this, what more could he possibly want?

He looked over at Charlie who was holding on to his armrest pretty tight. The whole thing was a little scary, but he knew Charlie was grinning as much as he was under that visor.

The view from up here was spectacular. He had been so focused on landing last week that he hadn’t truly taken in the grandeur of this vista. From altitude, the crater’s structure was much more apparent. In the distance, he thought he spotted the white of the rim, but that might just be wishful thinking.

The central peak was coming up as they had just crossed past apogee, or rather, apocynthion. He’d had a long time to run the numbers last night. Charlie and he had laid out their position on the map back inside Destiny. With the guys in the trench back in Houston, they’d calculated the engine burn almost perfectly.

A couple of precisely timed burns after launch kept them in a clipped trajectory that was, even now, bringing them down about 400 feet from the base of the central peak.

And what a sight it was. Like an alien pyramid it rose starkly from the flat ground around it. It was wider than it was tall, and presented a long sheet of rock, with a couple of minor peaks holding court at the base. Nestled between them all was a slightly rocky patch of ground that he’d begun to target.

Charlie was doing his best to call out altitude, but it was a guessing game and they both knew it. The LFU was relatively bare bones. It had a fuel gauge and a landing light indicator, but not much more than that. The astronaut was expected to control his altitude and his attitude and maintain a stable trajectory. To that end, the training process had stressed minimizing the number of burns and thruster firings during a flight. Jim had been admonished that two or three short stable hops were preferable to one disastrous one.

He was exceedingly glad that Houston hadn’t called off the whole thing. They’d have been within their rights to. The walkback rule had been suspended for LFU operations and from the start, much of the astronaut corps had considered this thing to be too risky to be practical. He had figured that his willingness to fly it in the first place, and his dedicated training regimen to that purpose in the second place, had secured his commander’s seat on this flight.

He watched one of the minor peaks rising slowly on his right and throttled up on the LFU.

“Okay, Houston. Here we go, 300 feet,” Charlie said. Jim tried to remember that Charlie had spent a lot of time prepping by looking at surface images from ascent videos, trying to understand how the terrain looked at various altitudes. The training had paid off.

“Coming down at 4, 60% fuel. Plenty of gas in the tank. Should be clear all the way.”

“You gonna come in over that hill?”

“Yeah, the flat spot, just past the base, on the right there.”

“Got it.”

“You got it?”

“Yeah. Good spot. 100 feet.”

“Gonna put her down nice and gentle.”

“Give her some gun. 50 feet.”

“Don’t want to scatter the rocks.”

“They’ll move, it’ll be fine.”

“Okay. Take out the horizontal… and here we go.”

“20 feet. Straight down. We’re in the lane Houston.”

McDivitt just held the stick steady as she goes for the last 20 feet. He’d managed to reach a flat spot that he estimated to be at least 50 feet on a side, but the LFU didn’t allow him to see where he was going on final descent.

The forward and aft landing lights came on at more or less the same instant and he killed the throttle. The LFU settled onto the basin with much more subtlety than the rover crash from the other day.

He grinned and tapped Charlie on the shoulder. Charlie heard his cue, “Houston, Tycho center. We’re down safe.”

For the next two hours, Charlie and Jim gathered 50 pounds of carefully selected samples from the lower levels of the central peak.

Between the anorthosite found at the rim, the peak samples, and the parts taken off of Surveyor VII, Charlie Duke and Jim McDivitt earned a rather warm place in the hearts of the engineering and geology teams back at Johnson Space Center. Along with those from the ejecta-blanket at the rim, the samples obtained on this day were among the first to be opened by scientists back on Earth. Some were found to contain traces of the impactor that had caused the crater and helped to establish the age of Tycho at approximately 108 million years old.

Despite the fervent hopes of many of the scientists and interested enthusiasts back on Earth, no significant magnetic anomalies were found.

12 April 1972

Apollo 17

37 hours after TEI burn

Callsign: Kitty Hawk

He’d had a hard time sleeping on Gemini as well. Charlie and Ron were out like lights, but he couldn’t just drift off.

His watch told him that it was about 2 am in Houston. He tried to remember who would be at the CAPCOM station at this time. He turned the headset volume to low and floated into the lower equipment bay. Not much for privacy, but it would do in a pinch.

It was awkward whispering into a headset mike. He’d learned as much with Ed White on Gemini IV. The beeping from each incoming and outgoing transmission was enough to allow you to talk in a normal speaking voice. Still, to help his crewmates sleep, he covered his mouth with his hand.

“Houston, 17.”

A sleepy voice replied, “17, Houston.”

“Who’ve we got down there tonight? Who drew the short straw?”

“This is Neil.”

“Armstrong! Hey man. How’s it going?”

“Just fine commander. Everything okay up there?”

“Yeah, just couldn’t sleep.”

“Can I help in some way? You want me to have the flight surgeon give you a recommendation?”

“Nah, just wanted to shoot the breeze. Hey, they were working on that new simulator before we left. Did they ever get it up and running?”

Armstrong perked up, “Yeah. I actually did the first test run on it the other day.”

“No kidding? They let a rookie christen her?”

“I’m not a rookie.”

“Ah… right… sorry man. I forgot. Shoot, yeah. You had one of the X-20 hops, right?”

“The last one. Before they shut her down.”

“How’s the new girl compare to that one?”

“Pretty similar actually. The feel is the same. She’s bulky on-orbit, but a dream once you get some air around her.”

“All the bells and whistles they have planned, it should be a comfy ride.”

“Agreed. They’re talking room for 6.”

“Wow. And you can’t beat a land-landing.”

“Oh yeah. You Gemini guys with the splashdowns… and then you’ve got to be pulled out by the Navy. It’s way more fun to come down at Edwards. No sea sickness and no sharks.”

“Don’t remind me.”

“The Iwo Jima checked in earlier today. They’ll be ready to meet you in a couple of days. We have you right on course.”

“I’m not worried. I think I’ll try to sleep again, but thanks for the chat.”

“Glad to help.”

“Oh… did they ever settle on a name for the new thing?”

“Officially it’s still the shuttle project.”

“But unofficially?”

“I overheard one of the public affairs guys talking about it the other day. He said they’re gonna start calling them Clippers.”

Last edited:

For more information on the Apollo mission to Tycho, take a look at David Portree's article here.

For information on the proposed lunar flying units, Mr. Portree's article has lots of information on their early development.

Mr. Drye's article on the lunar shelter has some insights into the thinking that went into the Aries.

For some information (and excellent illustrations) of lunar rover operations (both real and unrealized), take a look here.

For information on the proposed lunar flying units, Mr. Portree's article has lots of information on their early development.

Mr. Drye's article on the lunar shelter has some insights into the thinking that went into the Aries.

For some information (and excellent illustrations) of lunar rover operations (both real and unrealized), take a look here.

Is it possible for a summary post of Apollo missions to date for ease of reference?

I'd planned on a full summary after the last Apollo mission, but in the meantime I can give a basic rundown.

Using the alphabetized mission profiles:

Apollo 1 proceeded like OTL

Apollo 7 was the first manned launch. A C-mission testing the CSM in LEO. (Schirra, Cunningham, Eisele)

Apollo 8 was (like OTL) a C-prime mission that went to the Moon. (Lovell, Young, Anders)

Apollo 9 was a D-mission, but there was a failure during the LEM testing that severely limited its scope (McDivitt, Schweikart, Scott)

Apollo 10 was an E-mission which completed LEM testing.

Apollo 11 was the first G-mission - landing at the Ocean of Storms (Borman, Bean, Collins)

Apollo 12 was an H-mission - landing at the Sea of Tranqulity (Aldrin, Mitchell, Gordon)

Apollo 13 was the 2nd H-mission - landing in Fra Mauro highlands, exploring Cone Crater (Lovell, Haise, Mattingly)

Apollo 14 was an I-mission, modified to carry a separate module for orbital surveying. (Worden, El-Baz)

Apollo 15 was the first and only J-mission. A 3 day stay in the Sea of Serenity, exploring a wrinkle-ridge (Crichton, Anders, Roosa)

Before the launch of Apollo 16, a Saturn V was launched to deliver the core of the Olympus space station and the Beagle MOLEM unit to Marius Hills.

Apollo 16 was the first K-mission, which used two Saturn V launches (one manned, one unmanned). Landed in Marius Hills - 2 week surface stay. (Young, Keller, Swigert)

Apollo 17 was the 2nd K-mission. Landed in Tycho crater. First use of the LFU. 2 week surface stay. (McDivitt, Duke, Evans)

As a preview, I can tell you that Apollo 18 will be heading for the lunar farside.

Share: