You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Ocean of Storms: A Timeline of A Scientific America

- Thread starter BowOfOrion

- Start date

For those of you who enjoy this sort of thing, I modelled the new Webb building off of Sacramento's Ziggurat. (read more here)

It was built around the same time and timeframe and it was too interesting not to be a part of my timeline.

It was built around the same time and timeframe and it was too interesting not to be a part of my timeline.

That totally won't make people think human sacrifices are occurring there.For those of you who enjoy this sort of thing, I modelled the new Webb building off of Sacramento's Ziggurat. (read more here)

It was built around the same time and timeframe and it was too interesting not to be a part of my timeline.

I am being sarcastic.

This might just do nobody any good.

I think most writers would agree with the idea that the things you produce are like children. They grow up and start talking back to you. Sometimes they soar and reach new heights and everyone is impressed. Sometimes they develop bad traits and you feel embarrassed that your name is at the top.

I've been highly fortunate that so many of my chapters of OOS have brought me nothing but pride and joy, but this next one, presented below, is more like the kid who turns 18, never leaves the basement and won't go out and get a job. I don't feel like I wrote this chapter as much as let it pass through me, kicking it away as it left before it could drag me down with it.

Having said all that, I hope you enjoy.

I think most writers would agree with the idea that the things you produce are like children. They grow up and start talking back to you. Sometimes they soar and reach new heights and everyone is impressed. Sometimes they develop bad traits and you feel embarrassed that your name is at the top.

I've been highly fortunate that so many of my chapters of OOS have brought me nothing but pride and joy, but this next one, presented below, is more like the kid who turns 18, never leaves the basement and won't go out and get a job. I don't feel like I wrote this chapter as much as let it pass through me, kicking it away as it left before it could drag me down with it.

Having said all that, I hope you enjoy.

LII: Blood on the Regolith

Blood on the Regolith

14 June 1998

CF-512 Kitty Hawk

Altitude: 23 NM

MET: 00:02:37

Even knowing it was coming, he still grunted hard and winced as the shoulder straps dug into his flesh.

This was the fifth time he’d felt the kick from a Pegasus’s twin F-1’s cutting out and the surge of deceleration as the engine pod fell away. It was the fourth time he had felt the mighty Centaur’s single engine kick in and push him on to orbit.

The Centaur was the over-achieving middle-child of the space program. Each one lit like it knew this would be its only chance at glory. The powerful motor screamed out an angry death roar in protest of its inevitable fate. Centaurs lived for only a few moments. They died quickly, quietly, and alone.

As the Centaur pushed the splendid little spacecraft into orbit and fell away, Ken Borden, in the commander’s seat, let the acceleration and rumbles ripple through his bones. He enjoyed the view from the left-hand side of the cockpit. Over the next few minutes, the sky turned from blue to black.

“Kitty Hawk, this is Houston, SECO in ten seconds,” said the voice of CAPCOM.

Ken watched the little green mission clock and mentally matched it. He could feel the change in pressure on his back as the last of the fuel drained from the big tank at the rear.

The roar had died to a gentle hiss as the engine stopped. He waited for the heavy thwump of the pyros cutting the Kitty Hawk loose from the second stage.

Nothing happened.

He frowned. Over his right hand, there was a button marked CNT SEP. It had a soft white glow at the moment. There was a clear plastic cover over it to prevent any accidents.

Ken turned to Ron in the right-hand seat, “I’m gonna go to manual.”

Ron acknowledged with a nod but didn’t say anything. Rookies didn’t overstep their bounds when there was a situation at hand.

He opened the little cover and depressed the glowing button. No response.

Frustration spread from the corner of his mouth to his now wrinkled forehead. He tried the panel over his left shoulder. Another glowing button with the same label and cover. Another lack of reaction.

“Well, now it’s a thing. Houston, Kitty Hawk. We have negative Centaur sep. Repeat. Negative Centaur sep. Primary and backup. Rear radar is barber pole. Be advised I’m inputting the settings for ATO six.”

Ron pulled the short stack of index cards from the slot on his right sleeve. He thumbed through them until finding the one marked ATO 6. They both knew the input commands by heart, but Ron held them over the center console all the same. Together they looked back and forth between the card and the console as they entered the five parameters for the abort to orbit sequence.

The green and grey screen flashed “ATO 6”, then “CONFIRM”, then “READY”, then repeated the three terms. Borden rotated the handle by his right knee. They felt a jolt and then a push for ten seconds. Kitty Hawk was finally rid of her spent Centaur escort. As the engines died down, a couple of grunts came from the seats farther back.

Ron gave the next update, “Houston, Kitty Hawk. Rear radar active. Reading positive Centaur sep. ATO six OMS one complete.”

After they got confirmation from the ground, Borden pulled his headset mic down to avoid a national broadcast of his next words.

“Did you bring me a case of bad luck, rookie? Haven’t seen a failed Cen Sep in all my time doing this.”

A gravelly voice came in over their shoulders, “No, no, commander. That’s from me. I like to drag around dead rocket engines. Old habits die hard.”

Ron laughed. Some of the others joined in. Ken looked over his shoulder at the group of five in the back.

“You’re two-for-two, old man,” Ken said. He gave a thumbs up to the grey-haired passenger seated just behind Ron.

“Houston, Kitty Hawk. Be advised, our VP VIP is doing fine. Please give us the updated OMS numbers when you have them, over.”

19 June 1998

Olympus II Space Station

Lunar Orbit

Orbital Inclination: 86

“Tight squeeze, isn’t it, John?” Ken said, looking back at the elderly man floating through the small, circular hatch.

“I’ll manage,” the former Vice President replied, entering the miniature space station.

“Well, this is it,” Ken said, spreading his arms until he could touch the walls on either side of him.

Glenn shook his head, “Forget ‘Olympus’, we should have called it ‘Spartan’.”

Much like the original Olympus space station, this was little more than a habitable box in the sky. Olympus II was simply an elaborate cube with a modest life support system, lights, and heat. It had all the accommodations and luxury of a large walk-in closet. The cramped box was meant to be a waystation, a point of rendezvous for incoming craft from Earth to link up to surface landers.

Five of the module’s six sides were outfitted with universal docking ports that could accommodate any crewed spacecraft from any nation. The sixth side was occupied by a truss that stretched ten meters (a measurement born of international cooperation) and led to a logistics module that supplied solar power and the occasional burst of thrust.

Ken waved John over to one of the assorted portholes. “Here’s our ride downstairs.”

John peered out through the hardened double-glass, “Looks bigger up close. Like a Soyuz had a baby with a LEM.”

Ken nodded, “That’s the general consensus. But they’ve been...”

He was cut off by an incoming transmission. A clipped Indian accent came over the radio, “Orca, this is the Leonardo da Vinci, do you read?”

Ken put a hand to his earpiece and replied, “Leonardo, this is Orca, we copy. Mandar, are you ready to make your approach?”

“Affirmative. We are at five hundred meters and closing,” Mandar replied.

John watched as Ken floated to the side that he’d come to think of as the ‘ceiling’. The elder man joined the commander at the porthole.

“Watch this,” Ken said.

Over the next fifteen minutes, John Glenn got a lovely view of IASA’s newest spacecraft. The Leonardo da Vinci, first and, so far, only ship of her class, was a compact, biconic spaceplane. The sleek white vessel presented a gorgeous contrast against her grey and black background. Slowly, the ship backed into the docking port and Glenn heard the clicking of latches and the hiss of air pumps.

Once the hatches were opened, handshakes between the American and international crews took place and they began the process of transferring crew and cargo over to the Luna.

19 June 1998

Webb Operations Building

Johnson Space Center

29° 33’ 20” N 95° 05’ 38” W

“Flight, we have scheduled LOS. Starting the countdown for acquisition based on Luna approach parameters, over.”

“Copy that, Fido. Update me at ten minutes to acquisition,” Allison Curtin said from the Flight Director’s chair.

Her assorted controllers relaxed. With the Luna now on the far side of the Moon, nothing could really be done from Earth to assist or even monitor the situation. The automatic guidance programs would handle the descent down to Moonbase. From her chair in Houston, all she could do was wait for the lander to emerge over the Moon’s southern horizon. By that time, it would be on final approach. In the event of any emergency, Ken Borden and his crew would have to figure things out for themselves.

With the loss of signal the general mood of the control room had shifted from mild tension to monotony. Allison had no problem with her team abandoning their posts in the pursuit of coffee, snacks, or the nearest restroom. Being on the Flight Director console, she would not leave her chair without a better reason, but she did turn to her only source of entertainment: John Glenn’s ever-present Secret Service agent.

The man cut a handsome figure, though his suit had gotten wrinkled from occupying a chair for most of the last week. When they had first met, she had been offput by his all-business demeanor and the gun on his hip. Now she just thought of him as a good straight man to test out her material.

She swiveled her chair to face the agent, “So, what’s your worst-case scenario?”

He sat up, “You want to keep both hands on the wheel, here?”

“It’s fine. Nothing’s happening for a while.”

“They’re coming down to land!” he said, gesturing to the large screen at the front of the room.

She didn’t look away, “Computer’s got it. What’s your worst case?”

He frowned, “My worst case is you not doing your job and scattering my protectee all over the Moon.”

“Trust the damn computers. Worst case?”

He sighed, “Death. Kidnapping. Iron getting taken hostage.”

“Taken hostage?” she asked.

“Release Tim McVeigh or I’ll kill the VP,” he said, deadpan, emulating a theoretical terrorist.

She shrugged, “So, what would you actually do if someone threatened him up there?”

“Well, for sure I’m going to blame you,” he said.

She nodded, “How about after that?”

“I really don’t know, but I’m sure shouting will be involved,” he said.

Image Credit: I found this on the internet a long time ago, tweaked it, and forgot where it came from. If anyone recognizes it, please let me know.

19 June 1998

Moonbase Outpost

Expedition 32

Day 47

Courtney Pinton had to use so much force to open the tripod legs that she thought she would break the whole assembly. Out on the surface, parts tended to stick a bit, and getting machinery to unfold could be a problem at times. If she had thought about it, she’d have opened the legs back in the airlock, but it was too late for that now.

“Okay, Houston. I’m mounting the camera now. You should have video in a minute,” she said.

“Roger, Courtney. Just give us a good wide shot so we can see the ladder and the hatch,” came the reply.

She framed the scene as best she could. Her degrees were in chemical engineering, not cinematography, but she was the junior astronaut on the engineering team. This wasn’t the first time she’d had to try her best at a task she wasn’t quite suited for. Truthfully, she didn’t mind a bit. There was no such thing as a bad reason to go outside. She figured that Diane, the engineering team leader, sometimes gave her things like this as a reward and not a hazing.

She switched over to the base channel and spoke to the control room, “Can you patch me into the public relations feed? Receiving only. I don’t want to talk, but I need to hear what they’re saying.”

There wasn’t even an acknowledgement. She just suddenly heard the voices in her ear. They were live on a couple of channels who had wanted to cover this. It wasn’t exactly breaking news, but the twenty-four-hour cable news people seemed interested.

She could hear CAPCOM down in Houston, “Okay, John. We can see you coming down the ladder now.”

“Roger,” said the gravel-voiced septuagenarian.

Courtney watched him carefully descend the ladder. The folks back home wanted to see the old man come down and walk around like Frank Borman, but it was just theater. She gave a phantom tap to the rosary beads under the hard shell of her space suit. This wasn’t a great idea. These days, a newly arrived Luna got towed inside Dome Two and the crew stepped out in shirtsleeves. She tensed a bit as he hopped down to the Luna’s footpad.

They’d put down at the far end of Huffman Prairie, beyond the two constructed landing pads. It wouldn’t do to have the Great American Hero walk across a patch of canvas just to take a ceremonial step in the dirt. The Vice President would take his first steps in the lunar dust as God intended. It was amazing they hadn’t given him a white silk scarf and an old pair of aviator goggles to wear over the hard suit.

He stepped out onto the surface, turned, and gave a gleeful little laugh. She didn’t blame him. Overwhelming joy was a common reaction for this most uncommon of experiences.

In her ears, she heard the voice of an anchor from GNN, “Vice President John Glenn, a seventy-seven-year-old American, standing on the surface of the Moon.”

With perfect timing and a politician’s precision, Glenn spoke to a hushed audience, “A long time ago, I left the Earth in the spirit of friendship. And it’s in the spirit of friendship that I’ve come to the Moon today. From the bottom of my heart, I want to thank everyone responsible for this journey.”

Ken spoke to him over the radio, “John, turn to your right a little bit and take a look over that horizon.”

From twenty yards away, Courtney watched as he did just that.

“Oh, that view is tremendous!”

22 June 1998

Moonbase Outpost

Expedition 32

Day 50

“Vice President Glenn, we welcome you to Sunrise on GNN. It’s certainly a thrill for us to be calling you there on the Moon. Can you tell us about life on the lunar surface?”

Glenn slipped into his politician’s cadence with the ease one might enter a warm bath, “Oh, Karen, I can’t tell you what a thrill it is just to be here, sharing these cramped corridors with a dozen of humanity’s finest minds. The coffee is terrible, the bed is about half a foot too short, and the whole place smells like machine oil, but I tell you, this is the most fantastic destination I’ve been to in all my years.”

“That’s an interesting way to put it, sir. But you say you’re having a good time?”

“Absolutely. I feel about twenty years younger than I did back on Earth. The lower gravity makes life so much more comfortable. It’s a very different feeling than being weightless. In zero gravity, you’re constantly aware of your own body and inertia. You have to think about how you’re going to push off a wall or what you’re about to bump into next. Up here, it’s different. The one-sixth gravity is enough so that you still have normal sensations when you’re walking or standing or anything else, but what it does is make you feel stronger, lighter. Tired muscles get a break. Old bones don’t feel so heavy. It’s marvelous, perfectly marvelous.”

“We’re glad to hear that, sir. I understand your expedition will focus on the effects of low gravity on aging. Do you envision some kind of retirement facility in space in the distant future?”

“Hopefully not too distant, let me tell you. I hope that one day I can get Annie up here to enjoy this just like I am. With the strides that have been made so far with commercial flight, I think it’s possible that we could see something in low-orbit within the next ten or twenty years. I think it would be wonderful if we had some program that would let our wounded veterans take advantage of this environment as a form of therapy. The possibilities are really endless.”

“And how long will you be staying, sir?”

“Only a couple of weeks, I’m afraid. They’re sending me back down with the outgoing crew, but I tell you, they’ll have to go looking for me, because I plan to hide when they try to take me out of here. I’m having much too good of a time.”

“Thank you for speaking with us this morning Mr. Vice President. We wish you a good flight and a safe trip back home.”

“Thank you, Karen. And my great thanks to everyone back on the ground who made this trip happen.”

“Coming up after the break, we’ll be speaking with Jim Carrey, star of the new film The Truman Show, which hits theaters this Friday. After that, Bryan will take us out to Las Vegas for the big weigh-in. Stick around and we’ll have some fun, here on Sunrise.”

24 June 1998

Moonbase Outpost

Expedition 32

Day 52

He winced as they pulled the needle out of his arm. Blood samples were a small price to pay for a trip to the Moon, but that didn’t make them any less painful, or annoying. He’d been pricked and prodded twice a day for the last two weeks. On the ground, in orbit, and now on the Moon. The vampire jokes had already run stale. Now all he could do was grin and bear it.

He rose from the table and snuck a peek at the big taupe computer monitor on the end of the medical desk. There was no call for privacy, but he couldn’t make head nor tail of the numbers in the charts. No matter how much value there was to the medical knowledge gained on this trip, he doubted he’d understand a word of it himself.

“Shall we head down to the gym?” he asked. He looked forward to the exercises they had him run through each morning. It made him feel like quite the strongman. A call back to the salad days when he had walked amongst giants.

Sheila Davenport, the base’s medical officer, turned toward the door, “Sure, let’s…”

The base’s emergency claxon horns began to sound an alarm.

Sheila put a hand on his arm, and they paused mid-stride to listen to the announcement, “All hands. Eagle Fourteen is on approach and having difficulties. Ready Team One to emergency positions. Everyone on the surface, please stop all movement and do not approach Landing Pad Two.”

John nodded at the words and offered up a short, silent prayer for the crew aboard Eagle XIV. Sheila poked her head out of the door and beckoned him with a hand wave. He followed her into the hallway.

A moment later they arrived at Base Command and stood outside the open door. John listened to the radio chatter as Eagle made its final approach.

Ken Borden was at the controls, having just returned from a two-day jaunt to the rim of Faustini. Also on board were a pair of geologists who, based on the radio calls, must be gripping the handholds with white knuckles.

“Base, this is Fourteen, coming through five-hundred now. Can you confirm my fuel telemetry data, over?”

“Roger, Fourteen. We show you at six percent.”

“Seal your visors. Prepare for landing,” Ken said to his passengers.

“Fourteen, Base. Watch your drift. You are approaching the red line on horizontal velocity.”

“Very aware of that, Base. Thanks,” Borden said. John could hear the annoyance in his voice.

“Ready team is on standby, Eagle.”

“Three hundred, two-fifty…”

“Four percent, Eagle,” came the reply.

“Not gonna make it to the pad. Just gonna put down here. Killing h-dot.”

John grimaced. He could read the data projected on the front wall. Eagle was almost out of fuel and still more than two hundred feet up. He had gone bingo fuel in fighters before, but even then, he was able to glide. Once her fuel gave out, Eagle would take on the physics of a very sophisticated rock. The only thing that would arrest her fall would be sun scorched regolith.

“Easy, Ken. Put her down,” John said, whispering to himself.

“I’m gonna cut and save what I have left for the final,” Borden said.

“Okay, Ken. Use your best judgement,” was the reply.

John watched the green dot that represented Eagle XIV start to sink a bit more slowly. She was ballistic now. It was now a matter of Ken’s nerve against gravitational pull.

“Fifty feet, she’s chugging,” Ken said, reporting the engine starting to sputter.

“One percent,” came the reply.

“Twenty. Bingo. Dead stick. Hang on everyone.”

The radio crackled and silence filled the space for several seconds.

“Fourteen, Base, report!”

“Moonbase, this is Eagle Fourteen. We are down. Looks like we came down in a dusty patch. No leaks. Crew and structure okay. Request that you send a rover to come pick us up. I have us about eight hundred yards out. Can you confirm?”

“Roger, Fourteen. Just glad you’re okay. We’ll send a retrieval team. Stay put and we’ll come to you.”

“Copy Moonbase. Standing by,” Borden said.

Two hours later, in the recreation area of Dome Two, Ken Borden held court as about half of the lunar population gathered to listen to his account. John Glenn, always eager to hear an aviator’s tale, stood at Borden’s right hand, in rapt attention.

Borden’s hand movements were bombastic as he recounted the close call. “We had a couple of heavy ore samples in the cargo hold. When we launched out of Faustini, they must have snapped loose from the restraints. I could feel the center of weight shifting. Trim characteristics shot to hell. I had to burn a lot of fuel and RCS to keep her stable. By the time I got her figured out, we were over the foothills. Had to burn hard just to get back here. By then, it was just a game to see which would give out first. Fuel or trim.”

Stanley Raines, the current base commander, joined the group, flanked by a pair of subordinates. With faux anger he challenged the veteran pilot, “What were you trying to prove, Borden? That you’re good to the last drop?”

“Just trying not to die for some rocks, Stan,” Borden said.

“Amen to that, brother,” Raines said. He patted Borden on the side of his arm, then turned to the group, “Okay then, you all have jobs to do. Back to work!”

26 July 1998

Moonbase Outpost

Expedition 32

Day 54

Glenn settled into the chair next to Stanley and took a sip of water. The doctors had been urging hydration every time they drew a breath, and he figured the best way to stop hearing that request was to comply with it.

With some downtime between his morning and afternoon exams, he had chosen to spend this brief respite inside Base Command, watching the trio of monitors at the far end of the room as they showed the various teams operating outside.

His headset intermittently crackled with the dialog of research and maintenance as the work went on around the base. Voices came in from the crest of Shackelton, from the engineering workshops down the hall, from the geology backrooms in Houston. All of it funneled through this small, cramped command center. This was the heart of lunar operations and even the minor chatter had an exhilarating effect on the aged aviator.

“ETC, Houston. We’re seeing good readings on panel twelve. We’d like you to move on to the next one, please.”

“This is Pinton with Tanker Two. On station out at Eagle XIV for refueling.”

“Geo Team Bravo, preparing to extract the core sample. Marcus, stand clear of that.”

“Command, this is Ron and Mandar out in Rover Three. We are passing the halfway beacon for the traverse out to Sagan.”

Glenn drank it all in, sipping his water as he watched the Bravo team pulling up a long cylinder of dark grey stone, extracted from more than fifty feet below the surface. He gave a low whistle as the regolith saw sunlight for the first time in untold eons.

“Okay, clamp the base there. Yeah. Maria, you want to grab that other end there? Perfect.”

SKREEEEP!

A shrieking, shrill whistle filled his headset with sound just for an instant. He pulled off the unit and looked at it for a moment in bewilderment. Looking up, he saw a similar look on Stanley Raines’s face.

“What the bloody hell was that?” Raines asked.

“Command, this is Bravo Team Lead. Did you see that flash out to the west of us?”

“Uh, negative, Bravo Team. We had an audio anomaly there. Can you tell us what you saw?”

“Audio anomaly? That’s weird. No, we saw a flash, over the ridgeline to the southwest. Play back my helmet cam feed. You should see it.”

“Any secondary indications? Seismic tremors or…”

“Negative, base. Might have been an impact, but if it was, it’s small.”

Stanley Raines looked wary. He put a hand between his microphone and his mouth, “Meteor strikes don’t mess with our radio signals. What the hell was that?”

The staff in Base Command had no answer.

Raines hit a button on his control panel and spoke into his mic, “All surface teams: report in immediately.”

“Uh, Geo Team Bravo, reporting in.”

“Engineering Team Charlie, all secure at the solar farm.”

“Rover Three, en route to Sagan. Everything A-OK.”

A silence passed over the room.

“Courtney? Pinton? What’s your status out at Eagle Fourteen?”

Dead air.

Raines snapped his fingers in frustration and spoke, “Get me Courtney’s feed.” He keyed his microphone again, “Tanker Two, report!”

Nothing. John looked up at the big screen in time to see a feed of grey-white static fill the space.

“Oh God,” Raines said.

It only took a heartbeat for him to return to his duty.

“Bravo Team, Charlie Team. We have a problem out at the Eagle XIV site. Drop what you’re doing and get out there ASAP. Use caution on approach.”

Raines didn’t wait for an acknowledgement before opening the Base’s main intercom circuit. “All personnel, this is Base Command. We have a potential emergency situation. All medical personnel, stand by for further instructions. Emergency crews, please move to your assigned stations.”

In the lighter, faster, unpressurized dune buggy, Charlie Team was the first to make it over the foothills to the Eagle XIV landing site. They surmounted the last ridge within eight minutes of the call to move. It took a moment for Charlie Team to realize what had occurred.

“Uh… oh no. Command, uh, this is Charlie Team. There’s been an explosion. We’re moving through debris on approach to the site. Eagle Fourteen has suffered major damage. Catastrophic.”

“Any sign of Courtney?” Raines asked.

“Nothing yet, we’re looking. Stand by.”

Raines gripped the back of his chair. He watched the forward screen like a hawk, seeing regolith interspersed with scraps of various metal.

“On the ground. Courtney? Courtney? Over here, Steve.”

“Is she alive?” Raines asked.

“Base, this is Charlie Actual. I’ve found Courtney. Her helmet has been compromised. The faceplate is cracked. No life signs.”

26 July 1998

James Webb Operations Building

Houston, TX

29° 33’ 20” N 95° 05’ 38” W

With tensed fingers, Ryan Grimm gripped the side of the podium. He cleared his throat and looked out over the assembled press and photographers. The lights at the back of the room blinded him. There was a glare on his glasses. He took them off and put them on the table. He had the notes memorized so there was no need to read them.

Squinting through the discomfort, he gave up trying to focus and allowed his eyes to settle towards the bank of cameras. No matter what happened, there would be bigger things to talk about than his mannerisms.

“Again, just as a supplement to the statement from Director Krantz, the following are a few basic facts about this tragedy.”

“At approximately eleven forty-eight this morning, Houston time, astronaut Courtney Pinton was killed in a mishap that took place on the lunar surface. Astronaut Pinton was in the process of refueling the Eagle Fourteen lander which was located about a thousand yards away from Moonbase. Astronaut Pinton is survived by her parents, James and Marjorie Pinton of Eastlake, Indiana, and her sister, Sherry Cartwright of Santa Fe, New Mexico. Per her family’s wishes, the body of Astronaut Pinton will remain on the lunar surface where she will be interred.”

“The cause of this mishap is currently under investigation and until that report is made, all spacecraft at Moonbase are grounded, all refueling operations are suspended.”

From the third row, one reporter decided to jump the gun on questions, “Is the astronomy team still going to the Sagan site?”

Grimm took the question, “The radio astronomy team arrived at the Sagan Observatory around six p.m. this evening. They will remain there, per the previous schedule, through the 2nd of July.”

The floodgates opened. Hands shot up like spikes coming out of the floor.

“Why was Pinton alone on the surface?”

“Have there been previous problems during refueling operations?”

“Is the Eagle fleet being grounded?”

“Will Congress initiate an investigation?”

“Will Eagles eighteen through twenty be completed and launched?”

“Has the Secret Service asked for Vice President Glenn to be evacuated?”

“Who is responsible for astronaut safety during surface walks?”

Grimm allowed the wave to crash on him. Better that it should hit public relations than the director. As the tide settled, he relaxed his grip on the wood and lifted his hands in a gesture of calm.

“Ladies and gentlemen, I know you all have many questions about the mishap itself. At this time, I cannot speak to the cause or the changes that will occur as a result. Those are the purview of the investigation. Allow me to assure you that everything that should be done is being done. All Moonbase personnel are secure, and the investigation will proceed with clarity and focus.”

Then the hands shot up again.

27 June 1998

Moonbase Outpost

Expedition 32

Day 55

John gave a tentative knock to the hatch combing for the bio lab. He felt a bit awkward, both at the situation and his desire to insert himself into it. But you didn’t live the kind of life he had without a considerable reserve of initiative.

Within the cramped space, the body of Courtney Pinton lay on an exam table, still in her space suit. The two living occupants of the lab conferred at the far end of the room.

Diane Griss was currently the leader of the engineering team for Expedition 32. She was set to transfer out and head back to Earth with Glenn at the conclusion of this overlap between crews. With Pinton being her subordinate and the mishap occurring during an engineering operation, she was now living under a microscope with a quarter-million-mile lens.

Her counterpart, Sheila, had been a near constant companion to John since before they left Earth. Glenn hoped that relationship would provide him with some cover as he was about to make an awkward suggestion.

The two looked up from a quiet discussion as he entered.

“John, you probably shouldn’t be here,” Sheila said. Her tone was empathetic, but professional. “I can’t imagine the Secret Service wants you next to a dead body.”

Glenn put up a hand to stall for time, “I came to offer my services.”

Diane replied, “I’m sorry?”

“With the investigation,” Glenn clarified.

The two women exchanged a glance, “We appreciate that, John, but it’s being handled.”

“That’s very kind of you, Mr. Vice President,” Diane said, talking over Sheila a bit.

“I’ve been on mishap boards before,” Glenn said.

“Oh yeah?” Diane said.

“I was a test pilot. Mishaps are a part of life. I just think you might could use an extra pair of hands and eyes, here. I figure everyone else here has duties and schedules that are already laid out…”

She paused. Her eyebrows went up and her head tilted. She pondered for a moment, “If you’re angling for more surface time, this isn’t the…”

“No, no, no. I just wanted to pitch in,” he countered.

Her mouth wrinkled into a pensive frown. Her shoulders loosened a bit, “I suppose, as a temporary project, assuming there’s no objection from the good doctor here,” she said, looking to Sheila.

“Actually no. As long as you’re careful and don’t overdo it,” Sheila said.

Glenn smiled, “Where do we start?”

Diane nodded to Sheila, “Sheila is about ready to start her autopsy. While she does that, we’ll go investigate the accident site.”

27 June 1998

Eagle XIV Investigation Site

Expedition 32

Day 55

With the exception of the astronomy team, who were beyond the horizon, John and Diane were the only two astronauts outside the base. While that wasn’t entirely unusual, it did give John a certain historic thrill. He had many friends who had gone to the Moon in pairs and he tried to imagine, for a moment, that he was back on an old Apollo flight, alone with just his LMP and the distant voices of mission control.

The effect was largely ruined by the crisscrossing tracks in the dust. Whatever treasures the territory around Moonbase held, the one adjective it could no longer possess was “pristine”.

He and Diane had discussed the autopsy during the drive out. There was little that the doctor would tell them that could not be surmised already. Pinton had died from a suit breach. The mechanics of it were unpleasant, but the fact that debris had compromised her face plate told them nothing about the source of the debris, or the cause of the explosion.

Exiting the pressurized rover, they began at the perimeter, taking photographs and measurements. Diane had advised him not to discuss potential theories on an EVA. Their radio chatter would be heard back on Earth, and it would not do to give fuel to conspiracy theorists or armchair detectives or Monday morning engineers. All would have their moment in the sun before this was over. No reason to give them a head start.

With a few clipped comments to Houston regarding their progress and procedures, they spent several hours documenting the site from the outside in. More than half of their EVA time was spent at the base of the Eagle, going through what they could see of the remains.

Those remains told quite a story on their own. The lower half of the Eagle (John couldn’t help but think of it as the descent stage, though that terminology was more than a decade out of date), was blasted out. The engine bell had separated and was blown into the regolith, sticking out at an awkward angle. The legs had managed to hold their shape and were still in place, but they held a cracked plate of wires, hoses and the remnants of tanks.

An Eagle, like any other crewed spacecraft, had an abundance of tanks. Crew air, hydrogen fuel, oxidizer, water, helium, those were just some of the consumables that were housed in the lower half of the ship. Each one with its own tank and plumbing. John had seen diagrams of the internal Eagle hardware before, but had never crawled inside one to see for himself. The cracked edges and sharp jagged remains were a fearful sight to a man breathing canned air. John simultaneously felt urges both to touch and to back away. Human nature was ever-present, even on the Moon.

“John, hand me the Nikon,” Diane said, cutting through his thoughts. He turned to see her mounting the ladder on the forward leg.

He handed up the boxy digital camera and put a hand on her suit leg to help brace her, should the compromised frame collapse. She was taking something of a risk just by ascending two or three steps, but he did not challenge her.

Glenn looked up at her as she took various photographs. Diane was a leader, and now she was a leader who had lost someone. It was a terrible internal burden. No review board, no disciplinary committee, no Congressional witch hunt could ever dole out a punishment that would match her internal anguish. That kind of loss, of personal accounting, could hollow some people, but in Diane he saw resolve.

“Bring your light,” she said, pointing to a tank near the edge of the structure.

She dismounted the landing leg and walked around to where she had been pointing. With a gloved finger, she indicated a spot on the fuel tank, lower down, away from the jagged edge. John put his light on the area, and she began to take photos.

As she snapped the shutter, he inspected what she was aiming for.

The material had striations and random patterns of failure. Like a piece of metal compromised by rust and time that had become brittle. The light seemed to steep through the curved wall. Sensing what she was going for, he reached over and put his flashlight on the other side, letting the light come through from the rear. Sure enough, the cracked pattern appeared in relief against the dark, thicker areas. Diane gave him a thumbs up and continued recording images.

She stowed the camera and put a single finger to her faceplate, as though she was shushing him. He understood her request for silence.

She swept her arms from the area in question out away from the Eagle debris. She kept her arms in a single plane in front of her, sweeping as to indicate a straight line out onto the surface. Then she turned to walk the line and he followed.

Twenty yards away, they came to the remains of the fuel cart that Pinton had driven out to this site.

The fuel cart had the vague look of an 1800s covered wagon, minus the horses. It had a four-wheeled frame, with two seats and controls at the front. There was no pressurized cockpit, one drove the vehicle in a space suit, so the controls were oversized, for bulky, gloved hands. In the rear, occupying the back two-thirds of the vehicle, were a collection of cylindrical tanks, designed to hold the various needs of spacecraft that were to be serviced. A curved thermal shield gave the vehicle its Conestoga styling and one could imagine a pioneer at the controls, setting out for a lunar version of Oregon.

The cart was mostly intact. The thermal shielding was pitted in some areas from impacts but could likely be salvaged. The damage had mostly been confined to the rear. Two of the tanks had valves that had blown out. Others had bits of Eagle debris embedded in the side. One tank had been utterly wrecked by a large chunk of plumbing that had struck it dead center. John winced, realizing the same thing had happened to Pinton. Diane focused on a small area of lunar soil near the right rear wheel.

He saw footprints in the dirt. A few yards away he saw a flattened patch of dust, as though it had been swept. A red stain spread randomly from the area. Blood soaked regolith. The prints were where Courtney had been standing. The swept patch was where her body had fallen. The cluster of bootprints around it were the tracks of her fellow astronauts who had recovered her body.

Courtney bent her knees slightly and focused the camera on the rear right corner of the fuel cart. John couldn’t tell what she was going for, but he joined her in her crouch. She pointed silently to a metal rod that trailed down to the ground. One end was secured to a hinge on the vehicle, the other end had a hook and was barely touching the surface. Again, she gave him the shushing motion, but she spent several minutes photographing the rod from various angles.

After a bit more time surveying the site at large, she cut the silence with a simple command.

“We’d better be getting back,” she said.

27 June 1998

Rover 4

Expedition 32

Day 55

Thirty minutes later, they’d returned to the comfortable interior of the rover cabin. Once they were out of their suits, the priority became lunch. Ham and cheese for John, peanut butter for Diane. In shirtsleeves, far away from radio mics, they discussed what they had found.

“I know what happened,” Diane said.

John held back a look of shocked surprise, “Already?” was his compromising response.

She nodded, swallowing a bite, “Crazy check me on this, okay?”

“You got it,” said the aged aviator.

“Okay. We had an explosion. The source was the hydrogen fuel. Fair enough?”

“Yeah, I think we can rule out TNT,” Glenn said.

“For hydrogen to explode, it needs to come together with oxygen and an ignition source.”

“Still with you,” he said.

“So, safe to say that the fuel oxidizer is our oxygen source,” she said.

“Makes sense. But how did they come together?”

“You saw the tanks. Where I had you shine a light?”

“The cracks in the metal?”

“Yeah, they’re built to be light weight as much as strong.”

“Fatigue?”

“Brittleness in metals can come from a few sources. I think we can rule out moisture, but temperature variations and stresses… like the stresses from falling twenty feet with a full crew aboard…”

“The hard landing,” John said.

“Created cracks in the tanks. When Courtney started to fill them, the hydrogen and oxygen went right through the cracks and just started to fill the entire lower section,” Diane said.

“Turning it into a bomb,” John continued.

“And then it just needed a spark,” Diane said.

He nodded again, “Yeah, what do you figure for that?”

“Well, there’s no open flames obviously. But a spark serves just as well.”

“It can’t be bad wiring in the Eagle. It was shut down. No power going anywhere,” John said.

Diane shook her head, “The Eagle wasn’t powered up, but the fuel truck was.”

“Connected through the fuel line?” John asked.

“Exactly,” she said, swallowing from a water bottle.

“That’s connection, but it’s not a spark. The truck didn’t even explode. You saw it, it was mostly intact.”

“Yeah, that’s where I got stumped at first,” she said.

“At first?” he prompted.

“Hear me out. The Eagles are supposed to use the landing pads. They’re already cleared and flat and the locations are in the computers.”

“Sure,” Glenn affirmed.

“And on those landing pads, we have a grounding rod that we use when we refuel. First thing you do is clip the grounding hook to the rod on the pad,” she said.

“That little rod on the back of the fuel truck you showed me,” Glenn said, between a question and a guess.

“Yeah. Courtney would have known to ground the fuel truck, but she wouldn’t have had the landing pad facilities. So, she may have just stuck the grounding rod into the ground.”

“And that’s the only way it’s grounded?” Glenn asked.

“The treads on the tires aren’t connected to the rest of the fueling system. At least not electrically.”

“So, you’re thinking she forgot to use the grounding hook?”

“No. She obviously deployed it. We saw it down. Here’s the crazy part of my theory:”

“Okay,” he said.

“Courtney doesn’t have the clip, so she just puts the hook on the ground itself. Right on the regolith. That’s about as good as she could do, short of burying it. She might have kicked some dirt over it, maybe not. But either way, it wasn’t as secure as it would have been out on a pad. Then, she turns on the valves and the fuel starts to flow.”

“Meaning what?” John asked.

“As the fuel goes from the truck to the Eagle, the truck gets lighter. And not just a couple of pounds. It’s significant weight. As the fuel truck gets lighter, the suspension system slowly starts to rise,” she said.

“High enough for the grounding hook to lose contact,” John said.

“At that point, all it takes is electrons. Maybe she touched something, maybe it was a bad circuit somewhere in the pumps…”

“The charge goes down the fuel lines, into the Eagle…” John said.

“Which we know is grounded,” Diane continued.

“But before it can reach the ground, it finds an enclosed mix of hydrogen and oxygen,” John said.

“Yeah… a lot of things that shouldn’t happen all happening at once,” Diane said.

“Heck of a theory. Can we prove it though?”

“Maybe. If I can get something from the telemetry data.”

28 June 1998

Moonbase Outpost

Expedition 32

Day 56

The next morning, over protein bars and reconstituted eggs, John and Diane confronted the computer system.

The feed from Courtney’s helmet camera had confirmed that she deployed the grounding hook onto the regolith. The feed also proved the explosion came from the Eagle. That was obvious from their observations of the wreckage. What it did not show was how that explosion was triggered. She had been facing the Eagle when it went up. All Courtney Pinto saw was a flash of light. The camera cut out before any useful images could be recorded. Once it had been deployed, the grounding hook never again appeared in the recording.

“Let’s pull up the telemetry data. See if there was any kind of electrical issue,” John said.

Diane took over the keyboard and John was mystified as she swept through files and folders and accessed things he could barely understand. What was equally baffling was when she frowned after a moment and said, “There’s no telemetry data.”

“What?” John asked.

“There’s no damn telemetry data from the truck. Or from the Eagle, or the other rovers out on the surface at the time.”

“How could that be?” John asked.

“It’s saying the telemetry relay was down for maintenance at the time,” Diane said.

“The time of the explosion?”

“For…” she paused, checking the logs again, “the twenty-three minutes up until the explosion, and eighteen minutes after.”

“Down for maintenance?” John asked.

“It’s a monthly thing,” Diane said

“But it just happened to be at the worst possible moment?” John asked.

“Looks like,” Diane replied.

“Who picked that time?” John said.

“Does it matter?” Diane asked.

“It might,” John said.

She leaned over to read something off her clipboard, “Ricky Fredrick. He’s one of my technicians, just like Courtney.”

“We gotta ask him about this,” John said.

Ten minutes later they stood in the parts storage module, just off of Dome One, and met with Ricky Fredrick.

“It’s something that happens. Telemetry can be a lot of data through the radio channels. We have to service the antennae each month and when we do, we kill the telemetry downlink so that we don’t have to compromise voice communications with the ground.”

Diane nodded to John, “That’s true. It’s part of the routine.”

“But there’s no backup recording on the base?” John asked.

“Not that I’m aware of,” Ricky said.

“We don’t have that much data storage capacity. That’s why we send stuff downstairs,” Diane said.

John sighed, “I don’t have to tell you, this doesn't look good.”

“I agree, but I can’t give you what I don’t have,” Ricky said.

“You can give us an explanation as to why it was that time and not some other time,” John said.

“I have a checklist of things to do. I don’t make the list, I just do the things and check them off. I go one to the next until they’re all done. Sometimes things get added to the list or taken off, but I’m just the guy who crosses things out,” Ricky said.

“Who’s the guy who makes the list then?” John said.

“That would be me,” Diane said.

John and Diane had lunch in the bio lab. John with a pita full of sliced turkey and cheese, Diane with salad greens from the bio lab racks topped by a piece of salmon from the aqua farm. Mercifully, the body of Courtney Pinton had been moved to the cold storage freezer in the old section of the base.

With it being her lab, Sheila was there as a neutral ear to hear out their theories. She was also taking the opportunity to get another blood sample from John.

John was wrapping up his account of their investigation, “And so we asked the technician about that, Ricky Fredrick, and he’s saying it was just the next thing on his to-do list. We checked with Commander Raines. He confirmed that it was approved. The whole thing was supposed to take less than an hour and it did. Not sure where that leaves us.”

Sheila bit her lip, “Ricky Fredrick, you say?”

“Yeah, why?” Diane said.

“Um… just sit right there a moment, would you please?” Sheila said.

John held up his sandwich questioningly. They weren’t planning on going anywhere at the moment.

On tiptoe, Sheila stepped out of the lab and they lost sight of her down the hall.

“What’s this about?” John asked.

“You got me,” Diane said.

They shared a collective shrug and went back to chewing. In less than two minutes, Sheila had returned with a young woman in tow. John recognized her as one of the geologists.

Sheila made the introductions. “This is Nancy Waters from Geology. Nancy, will you tell them what you told me yesterday?”

Nancy gave Sheila a look that betrayed a certain embarrassment. She flushed slightly and then turned to look at the space between John and Diane, making eye contact with neither.

“Courtney and I bunked together over in Cabin Two. She was a great roommate. No issues,” she said, reservedly.

“Okay?” Diane said.

“The part about Ricky,” Sheila said.

“Oh God. Really?” Nancy said.

Sheila gave her a nod.

“Courtney and Ricky were Palmer pals,” Nancy said.

“Palmer pals?” John asked.

“Mr. Glenn, you’ve been a hero of mine since I was a little girl. I’d really appreciate it if I didn’t have to explain,” Nancy said.

John spoke, “Okay, well, somebody…”

“Did they break up?” Diane said, cutting him off.

“About two weeks ago,” Nancy said.

“Was it bad?” Diane asked.

“Not for her,” Nancy said.

Diane tilted her head a bit, “Okay. Noted. Thanks.”

“Don’t mention it,” Nancy said.

“I won’t,” Diane said.

The young woman scurried out of the hatch and bounded away like a frightened rabbit.

John spoke first, “What was…?”

“It’s a polite euphemism,” Sheila said. “A few years ago, they started sending condoms up along with the usual supplies,” she pointed to a small box by the door that he hadn’t noticed before, “It had become necessary after… certain events had transpired.”

John sighed, “Forty years later and it’s still the same story.”

“John, it’s just a facet of life out here that we can’t fully…” Sheila said.

John put up a hand, “There’s no need to be bashful. You’re all pretty tame by comparison. Ask Lola Morrow about nights in Cocoa Beach sometime. Ask her how many girls has ‘astronaut poisoning’ back in ’61.”

“We saw the movie,” Diane said.

John gave a small chuckle, “Well. The guy who cut off the telemetry readings had a fling with the woman who died.”

“That he didn’t mention,” Diane said, “Nor did he seem all that broken up about her death.”

“I’m not gonna cry over my ex-husband if he turns up dead. But I’m also not gonna kill him,” Sheila said.

John nodded, “I hate to say this, but this is now more than an accident investigation. We need to talk to Houston.”

29 June 1998

Webb Operations Building

Johnson Space Center

29° 33’ 20” N 95° 05’ 38” W

Allison Curtin listened as Diane finished her rehash of the report that she and John Glenn had filed yesterday. The report had been the subject of a series of tense late-night meetings amongst the brass, the secret service, and the engineering teams.

As for her own thoughts, her priority was, as always, crew safety and mission success, in that order. The situation with the explosion and the semi-questionable acts of Ricky Fredrick did not, in her eyes, pose any continued risk to safety or success. Her goal at this meeting was to keep the bigwigs from imposing any new rule or procedure that would cause problems for her teams on Earth or on the Moon.

Allison hadn’t been on-duty during the explosion, and she thanked her lucky stars that the first death on the Moon would not be a black mark on her career. She mourned the loss of Courtney as a work colleague, but, in her heart of hearts, she was a bit surprised that such a complex and dangerous operation as lunar colonization had managed to go on for so long without a life lost. It was a testament to the men and women of NASA.

As this quarter-million-mile roundtable was entering its second hour, her patience was wearing thin. Everyone had a take, and no one wanted to be left out. Earth was represented by Gene Krantz, Judy Resnik, Hoyt Ambrose from the Secret Service, and herself. On the Moon, John and Diane sat in Base Command joined only by Stanley Raines.

Judy Resnik, as always, was eager to get to brass tacks. “Bottom line is that this was just a preliminary investigation. Diane’s theory is great, but it’s just that, a theory. We need to send a proper investigative team to suss everything out.”

“So they can collect the evidence and piece the scene together? All the evidence hasn’t moved. And it won’t for about a million years,” Diane said.

Judy continued, “No offense to either of you, Diane, but I think you’d agree that you can’t be sure of anything from two days of work.”

“Fair, but I stand by my theory. And I’m even more confident that, no matter the cause, this was not an act of malice,” Diane said.

“I agree,” John said.

“Ricky along with the rest of the Expedition 31 crew was scheduled to fly back with John next week. At this point, I think the best thing is to isolate Ricky and bring Vice President Glenn home as soon as possible,” Resnik said.

“By isolate, do you mean imprison?” Stanley asked, under a raised eyebrow.

“Yes,” said Ambrose, from the Secret Service, bringing the room to a pause. “Until an investigation can prove no hostile intent, we have to assume that Fredrick poses a security threat, both to the base and the Vice President.”

Diane spoke, “I think that’s a bit much considering he was nowhere near…”

“Richard Fredrick’s parents were Cuban refugees. We’ve seen long-term operations where sleeper agents have come in from communist countries to act as saboteurs,” Ambrose said.

John Glenn broke the silence, “Hoyt, is it your opinion that Ricky Fredrick’s parents swam to Florida on the off chance their kid could become an astronaut and kill me one day?”

“Sir, my job is to protect you to the fullest possible extent,” Ambrose said.

John Glenn presented a chuckling smirk that he had relied upon many times, “Okay. I’m ending this now. Everyone there, please stand by for a moment please.”

On the monitor, the Earthbound participants saw Glenn whisper something to Stanley and Diane. They rose and left the room, leaving John Glenn seated. A moment later, Diane came back and handed John a small object. To Allison it looked like it might be a wrench, but with the resolution of the video system, she couldn’t be sure. Diane departed immediately after, only to be replaced by Stanley Raines, who was escorting Ricky Fredrick.

“What is he doing?” Ambrose said.

“Ah, Mr. Fredrick, thank you for joining me,” John said, loud enough to be heard over the feed.

“What’s going on?” Fredrick asked.

“The Secret Service thinks you might be some kind of threat to me. If that’s the case, I’d rather not look over my shoulder, so,” Glenn handed him the object he’d received from Diane, “Here’s a knife. If you want to kill me, have at it.”

Glenn spread his arms wide and turned slowly, showing his back to Fredrick. He finished the slow turn and faced the camera again. Ricky Fredrick looked questioningly at the knife for a moment before putting it down on the console.

“Hoyt, however much coffee you’ve been drinking, it’s time to stop. Gene, I don’t know what to tell you about the investigation, but Diane’s been on the money all the way as far as I can tell. If you want to spend a few million bucks on a launch just to prove her right or wrong, that’s up to you. As far as I’m concerned, there’s only one thing left to do to honor the memory of Courtney Pinton.”

30 June 1998

Moonbase Outpost

Expedition 32

Day 58

It wasn’t the most dignified procession, but frontier funerals were always sparse.

Ken Borden drove the dune buggy out of the Dome Two gate. In tow was the small cart which carried the improvised casket. The box, welded airtight, was much larger than Courtney Pinton’s frame, as it had to also house the space suit that she was to be buried in.

Behind the cart, a cluster of assorted astronauts and cosmonauts walked two-by-two. The trudging pace of the group was kept up for almost a full kilometer as they walked due North, towards the gibbous Earth.

The eulogies had been given within the base. All that was left was to bring Courtney to her final rest.

Arriving at the site, the rearguard of the group took up position parallel to the excavation dug into the regolith. The six pallbearers at the head of the line began their solemn task.

Stanley Raines has asked John to speak at the gravesite. He hadn’t wanted to offer words for a woman he had only known such a short time, but both the base commander and communications from the Pinton family had assured him that Courtney would have been honored by his participation. As well as he could in a bulky suit, he trudged to the front of the excavation.

In reverent silence, Courtney’s body was lowered on canvas straps. John held his breath for a moment as the mechanism began. Then he found his voice.

A small beep over the radio escorted his words across the void.

“In the sure and certain hope of the resurrection to eternal life through our Lord Jesus Christ, we commit the body of our friend, astronaut Courtney Pinton, to the stars and to the soil of this new frontier that she loved so much. May the Lord bless her and keep her. May He shine down upon her and be gracious unto her. May He lift up His countenance upon her and give her peace.

Amen.

Courtney, we thank you for your service both to us and to all mankind. You will be missed, and you will be loved. Until we meet again.

Ashes to ashes, stardust to stardust.”

Last edited:

Honestly, this is probably a investigator's dream and nightmare.

The scene is secure, nobody going up without authorization, debris isn't going anywhere, small suspect list.

The issue is, well, getting up there to confirm it before the possible suspect tosses any evidence.

The scene is secure, nobody going up without authorization, debris isn't going anywhere, small suspect list.

The issue is, well, getting up there to confirm it before the possible suspect tosses any evidence.

Also, just as an FYI to everyone, the 2023 Turtledove Awards are now open for voting. I'm glad to see that you can vote for as many timelines as you like.

Check it out here!

Check it out here!

This is absolutely amazing, and I can't express enough just how incredible it is that you've managed to have a murder mystery take place on the Lunar surface in the non-ASB sections of the forum and completely sell it. Good job!

Well, almost completely at least. There is one major issue.

Rocket propellent tanks are pressurized. They have to be, otherwise the liquids in them would boil off. Typically this is done with helium, released into the tank in question to maintain pressure inside.

The second one of the tanks was compromised, the internal pressure would start to drop. There are pressure sensors inside the tanks that would have noticed this immediately. If the structural failure occurred on landing, the pilot would have seen it on their instruments, and if it happened after they all got out and left, Courtney would have seen it when she checked the tank pressure before hooking up a fuel line to it. Because obviously, before you refuel any sort of propellent or pressurant tank in space, you check its internal pressure. This is true even if you're absolutely 100% sure that the tank is fine, because SOP is a thing for a reason, and it's also doubly, no, triply true if the vehicle it's on has just fallen 20 ft.

Actually, come to think of it, just going out and refueling the Eagle straight away makes no sense. It's just suffered a hard landing, the first thing anyone would do is send a team to check all of its systems before they start refueling it. But even if by some miracle that wasn't in the SOP, and by another miracle no-one thought it was a good idea anyway, it wouldn't matter too much. I would be very surprised if there were not tank pressure gauges mounted right next to the transfer line attachment points. Hell, even if there aren't (and there absolutely would be), the fuel pumping systems on the truck must have some way of telling the internal pressure of the tanks anyway, and then relaying that information to Eagle, so it can evacuate the excess helium from the tanks as they get refilled. Courtney would have gone to hook up the transfer line, seen the tank pressure is zero, and promptly realized the implications. The tanks were empty of fuel upon landing, so there isn't actually any danger to her so long as she doesn't start trying to refuel them.

But, let's say the SOP isn't to have a team inspect the vehicle before refueling it, that Courtney doesn't object to trying to refuel a vehicle with questionable structural integrity, and the fact the tanks are depressurized isn't concerning to her for whatever reason. Maybe they remove the helium pressurant from the tanks anyway when they're empty for some reason, and so she just has to refill both the propellent and helium tanks. Upon hooking up the transfer lines and starting the refueling process, hydrogen and oxygen would start leaking out of the cracks in the tanks. In order to produce an explosion that could actually do any damage, especially in the vacuum of space without any shockwave (I know it's inside the descent stage, but that's not airtight, so it would have to be very powerful to propel any debris at a high velocity), an enormous amount of propellent must have leaked out. We're talking a few dozen kilograms minimum. Probably more like a couple hundred. The transfer equipment is obviously going to have a way of checking the tank pressure during the refueling process, so Courtney would realize pretty quickly that the tank pressure isn't rising fast enough, assuming the computer doesn't notice for her. The implication of this - that there's a leak somewhere - is immediately obvious, and would be long before a dangerous amount of propellent was able to accumulate in the bottom of the descent stage.

In short, this particular failure mode would require an astronomical amount of bad design work and incompetence on Courtney's part to happen, to the point where I'm almost tempted to say suggesting it could is an insult to all the people at NASA? But it's just a story, I get being hyper-realistic wasn't the goal here, and I'll be damned to say I don't really enjoy the mystery and drama that it leads to. I suspect I'm being nitpicky in a bad way right now, so I'll stop. Again, good job on the update, and I'm looking forwards to reading the next one!

Well, almost completely at least. There is one major issue.

Rocket propellent tanks are pressurized. They have to be, otherwise the liquids in them would boil off. Typically this is done with helium, released into the tank in question to maintain pressure inside.

The second one of the tanks was compromised, the internal pressure would start to drop. There are pressure sensors inside the tanks that would have noticed this immediately. If the structural failure occurred on landing, the pilot would have seen it on their instruments, and if it happened after they all got out and left, Courtney would have seen it when she checked the tank pressure before hooking up a fuel line to it. Because obviously, before you refuel any sort of propellent or pressurant tank in space, you check its internal pressure. This is true even if you're absolutely 100% sure that the tank is fine, because SOP is a thing for a reason, and it's also doubly, no, triply true if the vehicle it's on has just fallen 20 ft.

Actually, come to think of it, just going out and refueling the Eagle straight away makes no sense. It's just suffered a hard landing, the first thing anyone would do is send a team to check all of its systems before they start refueling it. But even if by some miracle that wasn't in the SOP, and by another miracle no-one thought it was a good idea anyway, it wouldn't matter too much. I would be very surprised if there were not tank pressure gauges mounted right next to the transfer line attachment points. Hell, even if there aren't (and there absolutely would be), the fuel pumping systems on the truck must have some way of telling the internal pressure of the tanks anyway, and then relaying that information to Eagle, so it can evacuate the excess helium from the tanks as they get refilled. Courtney would have gone to hook up the transfer line, seen the tank pressure is zero, and promptly realized the implications. The tanks were empty of fuel upon landing, so there isn't actually any danger to her so long as she doesn't start trying to refuel them.

But, let's say the SOP isn't to have a team inspect the vehicle before refueling it, that Courtney doesn't object to trying to refuel a vehicle with questionable structural integrity, and the fact the tanks are depressurized isn't concerning to her for whatever reason. Maybe they remove the helium pressurant from the tanks anyway when they're empty for some reason, and so she just has to refill both the propellent and helium tanks. Upon hooking up the transfer lines and starting the refueling process, hydrogen and oxygen would start leaking out of the cracks in the tanks. In order to produce an explosion that could actually do any damage, especially in the vacuum of space without any shockwave (I know it's inside the descent stage, but that's not airtight, so it would have to be very powerful to propel any debris at a high velocity), an enormous amount of propellent must have leaked out. We're talking a few dozen kilograms minimum. Probably more like a couple hundred. The transfer equipment is obviously going to have a way of checking the tank pressure during the refueling process, so Courtney would realize pretty quickly that the tank pressure isn't rising fast enough, assuming the computer doesn't notice for her. The implication of this - that there's a leak somewhere - is immediately obvious, and would be long before a dangerous amount of propellent was able to accumulate in the bottom of the descent stage.

In short, this particular failure mode would require an astronomical amount of bad design work and incompetence on Courtney's part to happen, to the point where I'm almost tempted to say suggesting it could is an insult to all the people at NASA? But it's just a story, I get being hyper-realistic wasn't the goal here, and I'll be damned to say I don't really enjoy the mystery and drama that it leads to. I suspect I'm being nitpicky in a bad way right now, so I'll stop. Again, good job on the update, and I'm looking forwards to reading the next one!

Last edited:

Definitely agree. It's a heck of a way to get the private eye just in this for one more job, isn't it?This is absolutely amazing, and I can't express enough just how incredible it is that you've managed to have a murder mystery take place on the Lunar surface in the non-ASB sections of the forum and completely sell it. Good job!

Of all the things I've read on alternatehistory.com, John Glenn being Sherlock Holmes on the moon is one of the most inspired and unexpected things I've read, IMO, and that's a good thing...

Like that you referenced the 1960s escapades of the astronauts...

Good chapter and waiting for more, of course...

Like that you referenced the 1960s escapades of the astronauts...

Good chapter and waiting for more, of course...

Thank you all for the kind words. This last chapter was a bit of a trial to produce. Originally it was going to be a fairly generic account of John Glenn on the Moon, but I wanted an angle to make things interesting. Like the dog with the car, I got one, but didn't quite know what to do with it. Suffice it to say this is my first and last "murder mystery" (if that term even applies).

Then again, I do have a WIP for a murder mystery in the Star Wars universe, so never say never.

At any rate, I'll be happy to move on from this particular chapter and I'm looking forward to getting more OoS out here as soon as I can.

Then again, I do have a WIP for a murder mystery in the Star Wars universe, so never say never.

At any rate, I'll be happy to move on from this particular chapter and I'm looking forward to getting more OoS out here as soon as I can.

Gumdrop: The Monolith

Gumdrop: The Monolith

It had been cobbled together out of a couple of discarded containers that had originally held solar panels. The pet project of one of the engineers from the ’93 expedition who had been a fan of the film. The details, few though they were, had been lovingly preserved. The end result was as much a monument to passion as it was to science fiction. A man will go very far for his professional goals, but for his hobbies, there is often no limit to his attention to detail.

Clarke’s work prescribed the dimensions precisely, and his words were obeyed with abiding reverence. The black slab towered over every astronaut who posed in front of it, peaking at eleven feet, high, with three inches submerged by regolith for stability. Five feet in width and fifteen inches deep, the matte black finish soaked in the light. An imaginative astronaut felt like they might be standing on Kubrick’s set from thirty years before. A very imaginative astronaut might wonder if the sunlight that lit the slab would soon trigger a signal to one of the outer planets.

Silently the sentinel stood, guarding over the next great leap in the civilization of mankind.

Last edited:

Occasionally I'll have an idea that is too good to abandon, but too niche to fit within a particular chapter. Rather than leave these lost runts on the side of the road, I have decided to offer them to my readers as Gumdrops, (in honor of the Apollo 9 CSM). This is the first of what may become many more.

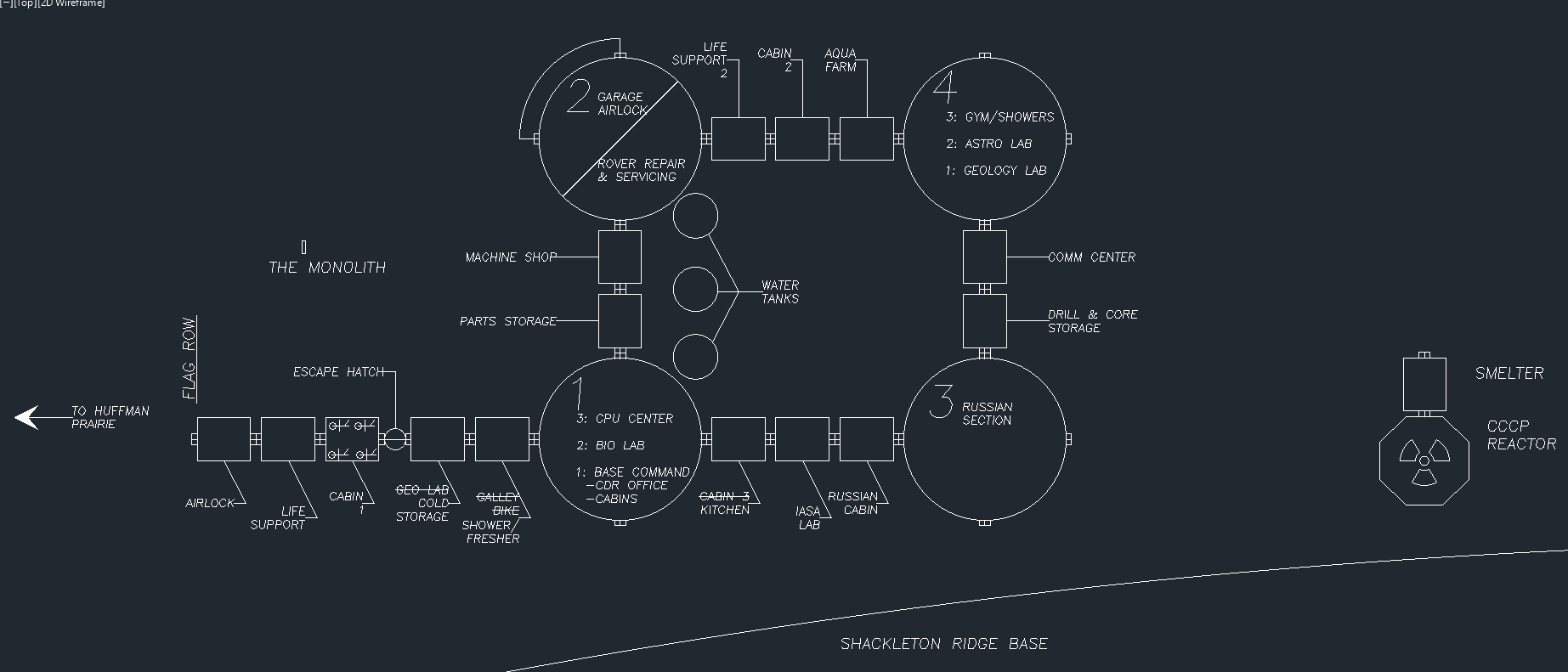

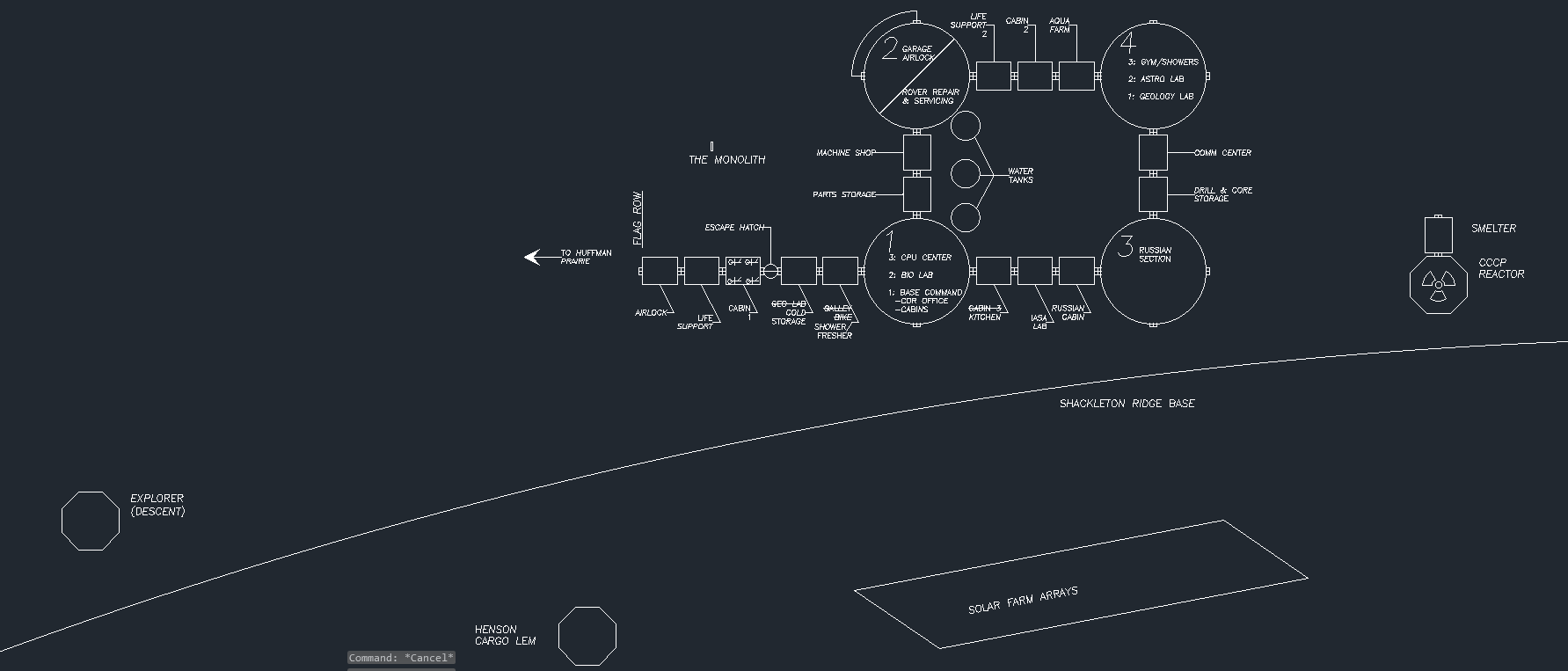

Here is an updated map of Moonbase c. 1998. The struck-through portions show the previous uses of certain modules. Moonbase, like every other home of human beings, evolves over time to meet changing needs.

Seems like "drill & core storage" and "comm center" on the east side could bear to be swapped (so the core storage is adjacent to the geo lab), and possibly something similar on the north side of the quad to put the aqua farm and life support adjacent?Here is an updated map of Moonbase c. 1998. The struck-through portions show the previous uses of certain modules. Moonbase, like every other home of human beings, evolves over time to meet changing needs.

View attachment 814261

View attachment 814260

I was just reading the Rumors of War chapter, and just one thing, @BowOfOrion--it's spelled Corpus Christi, not Christie (I live in Corpus Christi)...“Corpus Christie,” the driver said.

Good chapter, though...

Craig, I'm glad I get to explain this. Each of the Domes has airlocks at the outer edges with 90-degree spacing. This is done because they will (at some point) be used to attach future modules.Nice, clear map of Moonbase. I see only one airlock. Not that leaving Moonbase in the event of an emergency (i.e., fire) would be a ready option, but wouldn't a second airlock be prudent?

Half of Dome 2 also serves as a garage airlock (see the extra layer on the side as a large sliding garage door) which allows for vehicles to be driven inside and then worked on in a pressurized environment.

Share: