Just edited the January state elections post, as I somehow forgot Bavaria and Württemberg.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Nothing to Lose but Your Chains! / a German Revolution TL

- Thread starter Teutonic_Thrash

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 42 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Pseudo-Teaser for Soviet Russia 2 Pseudo-Teaser for Africa 1 Peace in the Balkans? Pseudo-Teaser for Africa 2 The White Counteroffensive 'Techno-thriller novel' Chapter 1 The Beginning of the End Part 1 Constitution of the Free Socialist Republic of GermanyJust edited the January state elections post, as I somehow forgot Bavaria and Württemberg.

What about Prussia?

I'm reasoning that the Prussian election would be held after the federal election.What about Prussia?

Last edited:

I'm reasoning Prussian election would be held after the federal election.

Oh, allright.

Prussia was basically half of Germany at the time, if not more. Incidentally, will the post-revolutionary government re-organise the German states into something a little more sensible? Because, honestly, the Weimar Republic's states are hideous to look at. Either merge the Northern States into Prussia or restructure Northern Germany into something that makes sense!

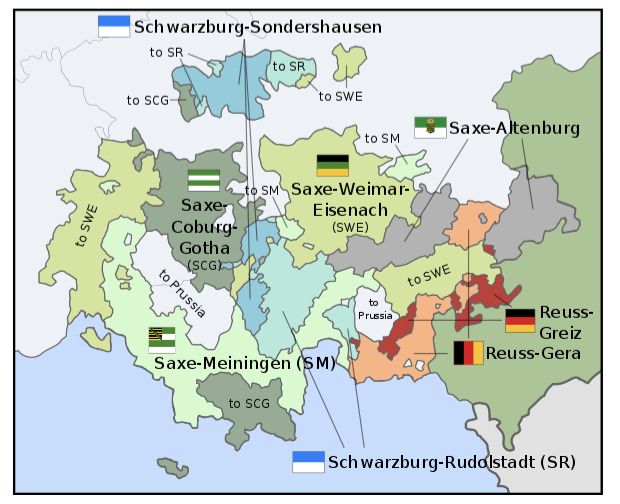

Just look at this map from Wikipedia:

Just look at this map from Wikipedia:

Deleted member 94680

Incidentally, will the post-revolutionary government re-organise the German states into something a little more sensible?

What do you mean by sensible? Neat, American style rectangular states? It’s pretty sensible to me, evolved over time with the possessions of the various ruling houses.

Either merge the Northern States into Prussia

That’s guaranteed civil war.

or restructure Northern Germany into something that makes sense!

Like what?

That’s simpler than it was. Thuringia was a collection of the Ernestine Duchies into a single state. Previously it looked like this:Just look at this map

Monitor

Donor

I think he means something a but like Germany uses today. Not rectangular, but somewhat organically grown. In all honesty, something should be done about prussia, the state is far to dominant. And if you can use that to make the other states look combined, great (helps with state level infrastructure projects if you do not need to coordinate with three other states to get it done...).What do you mean by sensible? Neat, American style rectangular states? It’s pretty sensible to me, evolved over time with the possessions of the various ruling houses

will the post-revolutionary government re-organise the German states into something a little more sensible?

I am having an internal debate about the state re-organisation. At the end of the day, the FSRD will be a nested-council based democracy organised on the basis of districts (unterbezirk -> bezirk -> oberbezirk). Here are the twenty-seven regions which the OTL party decided to organise on in 1922:something should be done about prussia, the state is far to dominant.

I imagine the post-civil war states will be somewhat similar.They were Berlin-Brandenburg, Niederlausitz, Pomerania, East Prussia-Danzig, Silesia, Upper Silesia, Eastern Saxony, Erzgebirge-Vogtland, Western Saxony, Halle-Merseburg, Magdeburg-Anhalt, Thuringia, Lower Saxony, Mecklenburg, Wasserkante, North-West, Eastern Westphalia, Western Westphalia, Lower Rhineland, Central Rhineland, Hesse-Cassel, Hesse-Frankfurt, Palatinate, Baden, Württemberg, Northern Bavaria and Southern Bavaria.

Monitor

Donor

Just as an Info, today Germany is organized in cities/towns, then Kreise, and then the Länder (So maybe change the names...)I am having an internal debate about the state re-organisation. At the end of the day, the FSRD will be a nested-council based democracy organised on the basis of districts (unterbezirk -> bezirk -> oberbezirk). Here are the twenty-seven regions which the OTL party decided to organise on in 1922

I would need to go Wikipedia diving to figure out why they are called Kreise... (I believe today Germany has around three hundred of those, but this I am absolutely not sure of).

Deleted member 94680

Kreise means circle in German. It originated in the HRE as a name for an administrative ‘unit’I would need to go Wikipedia diving to figure out why they are called Kreise... (I believe today Germany has around three hundred of those, but this I am absolutely not sure of).

Deleted member 94680

Fair enough. But the ‘complicated’ arrangement Germany had OTL was organically grown. This would be artificial and the people would see it as such. Especially those that have vested interests. Any rearrangement more than likely means weakening Prussia and that’s going to cause a lot of resistance.I think he means something a but like Germany uses today. Not rectangular, but somewhat organically grown.

Monitor

Donor

Yeah, but for a functioning democracy, Prussia needs to be weakened. It was one of the problems Germany had...Fair enough. But the ‘complicated’ arrangement Germany had OTL was organically grown. This would be artificial and the people would see it as such. Especially those that have vested interests. Any rearrangement more than likely means weakening Prussia and that’s going to cause a lot of resistance.

(Admittedly, the question is how functional the democracy will be, so it might be a mood point

EDIT: Organically grown can mean a lot of things. Especially if you have the HRE screwing everything up

Deleted member 94680

How do you mean the HRE messing everything up?Organically grown can mean a lot of things. Especially if you have the HRE screwing everything up. One can argue how organically grown that mess actually is.

You can’t argue it’s not organically grown as it was. It’s organically grown as it’s evolved over time. Land has been added and lost by the various states for political and dynastic reasons. But it’s slowly happened over time. To rearrange things all at once at the stroke of a pen is artificial.

You could just as easily make the argument that the boundaries of the Weimar states were the artificial products of dynastic whims and politicking utterly divorced from any natural communities or geographical regions. Like how Oldenburg has a small exclave in the Rhineland, Prussia has an exclave between Baden and Württemberg and northern Germany has all of these tiny, non-contiguous statelets. Indeed, the original pan-German liberal nationalists saw all of those dynastic statelets as artificial feudal impositions on the organic and natural German nation and sought to abolish them through unification.

It would have made more sense to break Prussia up into its constituent provinces and merge any enclaves into the administrative territory (or merge Prussian territory into them if it was more prudent).

It would have made more sense to break Prussia up into its constituent provinces and merge any enclaves into the administrative territory (or merge Prussian territory into them if it was more prudent).

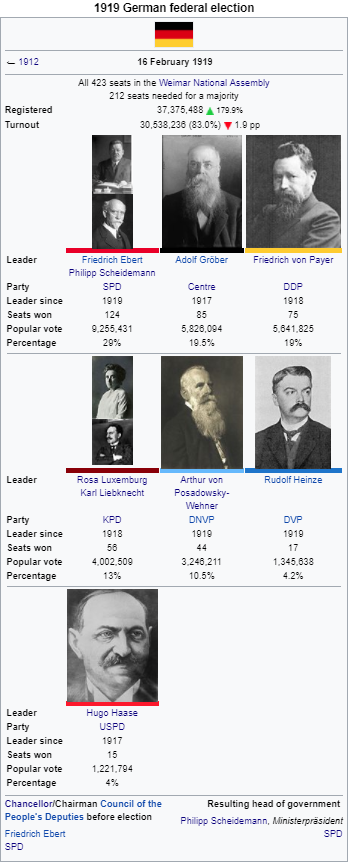

The German Federal Election of 1919

The German Federal Election of 1919

The Social Democratic Party had its share of problems going in to the federal constituent assembly election of 16th February. The crisis over the Polish insurrection had simmered down from its previous fever pitch, but a ceasefire was still out of the government’s reach and the re-ignition of the war with the Entente had been a very real possibility. The miners’ strike called in response to the undeclared war was also still ongoing, and the party’s coalition partner, the Independent Social Democratic Party, were proving themselves to be unreliable. On the other hand the SPD were still seen by a large portion of the working class, including an increasing amount of those in rural areas, to be the primary socialist party. To those who remained un-politicised, the SPD had brought universal suffrage, expansions to healthcare and welfare, and established the Socialisation Commission. Due to the party’s alliance with the right-wing political and media establishment, the government’s counter-revolutionary efforts (such as the utilisation of the Freikorps) were free from journalistic scrutiny and so their image remained untarnished outside of the industrialised cities. The party leaders Friedrich Ebert and Philipp Scheidemann were confident of their victory in the election and the subsequent establishment of a parliamentary liberal democratic republic.

The working class who were politicised however, were split in their allegiance. When the Communist Party had split from the Independent Social Democratic Party, most of the revolutionary left and centre of the USPD joined the new party. Those who remained were reformists, like party leader Hugo Haase, or cautious revolutionaries like Emil Barth. The USPD proclaimed its loyalty to the revolution and the establishment of a socialist council republic, but their continued coalition with the Social Democrats in the federal government was problematic at best to many workers who had been on the receiving end of the government’s repressions. The division in the USPD which was displayed at the Second All-German Congress of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Councils was also a decisive factor in dissuading proletarian voters from the party. The benefactor of the USPD’s weakness of course was the Communist Party. The split in the USPD had led to a number of famous figures of the left joining the new party: the stridently anti-war Spartacists Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg; leaders of the revolutionary shop stewards like Georg Ledebour and Richard Müller; and Willi Münzenberg, the leader of the Socialist Youth International. The congregation of such luminaries, combined with KPD’s uncompromising call for a socialist republic of workers’ and soldiers’ councils, acted as a magnet for those workers who considered the SPD to have betrayed their socialist principles for a grip on power.

The centre-right liberal part of the spectrum was occupied by the Centre Party and the Democratic Party; both parties ostensibly supported the foundation of the republic and the accompanying political liberalisation. Zentrum’s political Catholicism was an important, but not uncontested, part of the party’s program; Heinrich Brauns’ attempt to transform the party into a broader Christian People’s Party failed, and the Bavarian branch of the party split off to establish its own, more conservative, Bavarian People’s Party. Meanwhile the newly-founded DDP had been closely involved with the government; prominent party member Hugo Preuss was given the task of drafting the new constitution by Ebert and the SPD ministers. The base of support for the two major liberal parties were the middle class, upwardly mobile white-collar workers, parts of the rural population, and of course Catholics for the Centre Party. Further to the right were the National People’s Party and the People’s Party. Like the DDP they were both recent reshufflings of older parties; unlike the DDP, the DNVP and the DVP were both strongly opposed to the revolution, the new republic it had created, and left-wing politics in general. Conservatism, monarchism, nationalism, and Christian values were the primary characteristics of these parties, as well as, to a lesser extent, anti-Semitism and völkische sentiment. The incredibly wealthy strata of the middle class (industrialists and bankers), the rural population, and the remnants of the nobility were the main source of the DNVP and DVP’s support; the four large banks, Deutsche Bank, Dresdner Bank, Darmstädter Bank, and Disconto-Gesellschaft donated over thirty million marks to the centre-right and right-wing parties. There were other, regional, parties such as the aforementioned Bavarian People’s Party, the German-Hanoverian Party, and the Schleswig-Holstein Farmers’ and Farmworkers’ Democracy.

The change from plurality single-member constituencies to proportional representation and multiple-member constituencies, as well as the introduction of universal suffrage and the lowering of the voting age to twenty, resulted in equal parts excitement and dread among contemporary observers of the election. The ongoing miners’ strike and the Polish insurrection only exacerbated such an atmosphere. Ebert and the other SPD leaders expected to win a majority or at least a strong plurality of seats; they were to be disappointed. In the Entente-occupied constituencies of the Rhineland the Centre Party gained the most seats, except in East Düsseldorf where the Communists and Independents edged out in front. In Lower Bavaria the Bavarian People’s Party took the most seats, but in Upper Bavaria and Franconia there was a more even split between the BVP and the SPD. Over in neighbouring Württemberg the SPD came first, but the Democratic Party and Zentrum shared most of the remainder between themselves; Baden was also split fairly equally between the SPD, DDP, and Zentrum. In the Palatinate the SPD received a plurality of votes but was outperformed by the parties to the right when combined; Hesse displayed similar results. The industrial belt stretching through Thuringia, Saxony, Potsdam, and Berlin saw the strongest results for the KPD, with the SPD and USPD close behind them. In the parts of Posen which German forces controlled, the National People’s Party, the People’s Party, and the DDP gained most of the seats. In Silesia, the SPD gained the most seats in Breslau and Liegnitz, but in Oppeln Zentrum edged out ahead. In Prussia proper, the SPD won a comfortable first in the East but were only just ahead of the DDP in the West. Neighbouring Pomerania was taken mostly by the SPD, with the DNVP not too far behind in seats. In Mecklenburg, Magdeburg-Anhalt, and Schleswig-Holstein, the SPD and DDP were dominant. In the constituencies of Hanover-Brunswick, Frankfurt an der Oder, and Hamburg-Bremen, the SPD and DDP gained the majority of seats, along with some for the German-Hanoverian Party in Hanover. The constituencies of Weser-Ems were split equally between the SPD, DDP, and Zentrum, while the rest of Westphalia was split between the SPD and Zentrum. The soldiers in the east gave both of their seats to the SPD.

The Social Democrats did not receive the majority that they had been hoping for. However, with the aid of the Centre Party and the Democratic Party the government would have a majority in support of their constitutional plans which would lead to the creation of a representative liberal democracy. The government had already decided to hold the assembly in the relatively quiet city of Weimar, away from the revolutionary fervour of Berlin; the assembly would convene on the 1st March. Until then Ebert and his cabinet had to end the miners’ strike, implement a ceasefire with the Polish insurrectionists, and negotiate a peace treaty with the Entente. Completion of these tasks would not be easy. The SPD’s coalition partners in the USPD were demoralised by their poor showing in the election; Emil Barth argued that the party’s alliance with the SPD government had ruined their reputation among the industrial workers. Even the party leader Hugo Haase had trouble justifying the party’s continued place in the government, but he and the other members of the USPD’s right still thought that coalition with the Communists was the greater evil. The party’s leadership was paralysed by the debate, while the Communists took the advantage to argue they were the true workers’ party and that the SPD had betrayed the revolution to side with the reactionary liberals and conservatives. Alongside the federal election was the election to the state constituent assembly of Schaumburg-Lippe: the SPD won 8 of the 15 seats while the rest went to the right-wing parties.

* Compared to OTL, there is a leftward shift in the industrialised urban areas; mostly rural areas are generally the same as OTL. The BVP’s seats and votes have been grouped with Zentrum.

The Social Democratic Party had its share of problems going in to the federal constituent assembly election of 16th February. The crisis over the Polish insurrection had simmered down from its previous fever pitch, but a ceasefire was still out of the government’s reach and the re-ignition of the war with the Entente had been a very real possibility. The miners’ strike called in response to the undeclared war was also still ongoing, and the party’s coalition partner, the Independent Social Democratic Party, were proving themselves to be unreliable. On the other hand the SPD were still seen by a large portion of the working class, including an increasing amount of those in rural areas, to be the primary socialist party. To those who remained un-politicised, the SPD had brought universal suffrage, expansions to healthcare and welfare, and established the Socialisation Commission. Due to the party’s alliance with the right-wing political and media establishment, the government’s counter-revolutionary efforts (such as the utilisation of the Freikorps) were free from journalistic scrutiny and so their image remained untarnished outside of the industrialised cities. The party leaders Friedrich Ebert and Philipp Scheidemann were confident of their victory in the election and the subsequent establishment of a parliamentary liberal democratic republic.

The working class who were politicised however, were split in their allegiance. When the Communist Party had split from the Independent Social Democratic Party, most of the revolutionary left and centre of the USPD joined the new party. Those who remained were reformists, like party leader Hugo Haase, or cautious revolutionaries like Emil Barth. The USPD proclaimed its loyalty to the revolution and the establishment of a socialist council republic, but their continued coalition with the Social Democrats in the federal government was problematic at best to many workers who had been on the receiving end of the government’s repressions. The division in the USPD which was displayed at the Second All-German Congress of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Councils was also a decisive factor in dissuading proletarian voters from the party. The benefactor of the USPD’s weakness of course was the Communist Party. The split in the USPD had led to a number of famous figures of the left joining the new party: the stridently anti-war Spartacists Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg; leaders of the revolutionary shop stewards like Georg Ledebour and Richard Müller; and Willi Münzenberg, the leader of the Socialist Youth International. The congregation of such luminaries, combined with KPD’s uncompromising call for a socialist republic of workers’ and soldiers’ councils, acted as a magnet for those workers who considered the SPD to have betrayed their socialist principles for a grip on power.

The centre-right liberal part of the spectrum was occupied by the Centre Party and the Democratic Party; both parties ostensibly supported the foundation of the republic and the accompanying political liberalisation. Zentrum’s political Catholicism was an important, but not uncontested, part of the party’s program; Heinrich Brauns’ attempt to transform the party into a broader Christian People’s Party failed, and the Bavarian branch of the party split off to establish its own, more conservative, Bavarian People’s Party. Meanwhile the newly-founded DDP had been closely involved with the government; prominent party member Hugo Preuss was given the task of drafting the new constitution by Ebert and the SPD ministers. The base of support for the two major liberal parties were the middle class, upwardly mobile white-collar workers, parts of the rural population, and of course Catholics for the Centre Party. Further to the right were the National People’s Party and the People’s Party. Like the DDP they were both recent reshufflings of older parties; unlike the DDP, the DNVP and the DVP were both strongly opposed to the revolution, the new republic it had created, and left-wing politics in general. Conservatism, monarchism, nationalism, and Christian values were the primary characteristics of these parties, as well as, to a lesser extent, anti-Semitism and völkische sentiment. The incredibly wealthy strata of the middle class (industrialists and bankers), the rural population, and the remnants of the nobility were the main source of the DNVP and DVP’s support; the four large banks, Deutsche Bank, Dresdner Bank, Darmstädter Bank, and Disconto-Gesellschaft donated over thirty million marks to the centre-right and right-wing parties. There were other, regional, parties such as the aforementioned Bavarian People’s Party, the German-Hanoverian Party, and the Schleswig-Holstein Farmers’ and Farmworkers’ Democracy.

The change from plurality single-member constituencies to proportional representation and multiple-member constituencies, as well as the introduction of universal suffrage and the lowering of the voting age to twenty, resulted in equal parts excitement and dread among contemporary observers of the election. The ongoing miners’ strike and the Polish insurrection only exacerbated such an atmosphere. Ebert and the other SPD leaders expected to win a majority or at least a strong plurality of seats; they were to be disappointed. In the Entente-occupied constituencies of the Rhineland the Centre Party gained the most seats, except in East Düsseldorf where the Communists and Independents edged out in front. In Lower Bavaria the Bavarian People’s Party took the most seats, but in Upper Bavaria and Franconia there was a more even split between the BVP and the SPD. Over in neighbouring Württemberg the SPD came first, but the Democratic Party and Zentrum shared most of the remainder between themselves; Baden was also split fairly equally between the SPD, DDP, and Zentrum. In the Palatinate the SPD received a plurality of votes but was outperformed by the parties to the right when combined; Hesse displayed similar results. The industrial belt stretching through Thuringia, Saxony, Potsdam, and Berlin saw the strongest results for the KPD, with the SPD and USPD close behind them. In the parts of Posen which German forces controlled, the National People’s Party, the People’s Party, and the DDP gained most of the seats. In Silesia, the SPD gained the most seats in Breslau and Liegnitz, but in Oppeln Zentrum edged out ahead. In Prussia proper, the SPD won a comfortable first in the East but were only just ahead of the DDP in the West. Neighbouring Pomerania was taken mostly by the SPD, with the DNVP not too far behind in seats. In Mecklenburg, Magdeburg-Anhalt, and Schleswig-Holstein, the SPD and DDP were dominant. In the constituencies of Hanover-Brunswick, Frankfurt an der Oder, and Hamburg-Bremen, the SPD and DDP gained the majority of seats, along with some for the German-Hanoverian Party in Hanover. The constituencies of Weser-Ems were split equally between the SPD, DDP, and Zentrum, while the rest of Westphalia was split between the SPD and Zentrum. The soldiers in the east gave both of their seats to the SPD.

The Social Democrats did not receive the majority that they had been hoping for. However, with the aid of the Centre Party and the Democratic Party the government would have a majority in support of their constitutional plans which would lead to the creation of a representative liberal democracy. The government had already decided to hold the assembly in the relatively quiet city of Weimar, away from the revolutionary fervour of Berlin; the assembly would convene on the 1st March. Until then Ebert and his cabinet had to end the miners’ strike, implement a ceasefire with the Polish insurrectionists, and negotiate a peace treaty with the Entente. Completion of these tasks would not be easy. The SPD’s coalition partners in the USPD were demoralised by their poor showing in the election; Emil Barth argued that the party’s alliance with the SPD government had ruined their reputation among the industrial workers. Even the party leader Hugo Haase had trouble justifying the party’s continued place in the government, but he and the other members of the USPD’s right still thought that coalition with the Communists was the greater evil. The party’s leadership was paralysed by the debate, while the Communists took the advantage to argue they were the true workers’ party and that the SPD had betrayed the revolution to side with the reactionary liberals and conservatives. Alongside the federal election was the election to the state constituent assembly of Schaumburg-Lippe: the SPD won 8 of the 15 seats while the rest went to the right-wing parties.

* Compared to OTL, there is a leftward shift in the industrialised urban areas; mostly rural areas are generally the same as OTL. The BVP’s seats and votes have been grouped with Zentrum.

Last edited:

The actual numbers for voters may be off, so don't get too distracted by them.

The actual numbers for voters may be off, so don't get too distracted by them.

One way to accurately determine the number of votes that correspond to a percentage is to take the total number of votes, divide by 100 and then multiply by the percentage you need. For example if the total number of votes is 600, and you need to determine how much is 15% of the votes, just multiply 6 by 15 and you get 90 votes. That's how I do it.

Post-Election Realignment

Post-Election Realignment

The day of the federal election, 16th February, was also the date of the expiration for the second extension of the armistice with the Entente. Friedrich Ebert’s government devoted all of its efforts to secure another extension, but complications arose from French demands that the Polish rebels be classified as Entente forces. Accepting would be a tacit abandonment of Posen, but the alternative was a resumption of the war. The situation was out of the government’s hands anyway: most of the Deutsches Heer soldiers were mutinying, while the Freikorps who were still fighting had been declared outlaws. The government reluctantly agreed to the French demand and gained an armistice extension of eight months. Peace was not achieved however. Shortly after the ceasefire was signed the Freikorps began a southern offensive against Gostyn and Kosten, threatening Posen. Once those two towns were back under German control, the Freikorps decided to push on towards Posen from the south. Joseph Noulens, chairman of Poland’s Entente mission, unilaterally decided to retaliate and ordered a joint Franco-Polish army across the border to attack Ostrów. The Freikorps cancelled their offensive against Posen and diverted troops to defend Ostrów. A tough battle ensued, causing much damage to a city that had so far avoided a lot of the insurrection’s violence, and the Franco-Polish forces emerged victorious on 18th February. The government tried to downplay the escalation of the Polish rebellion by pointing to their success in negotiating a ceasefire and arguing that as such the strikers’ demand had been met. After twelve days of continuous striking the miners of the Ruhr and central Germany had been feeling the pinch of not working; the strike funds of the unions and donations from the local branches of the KPD and USPD were beginning to run out. Additionally the miners were convinced by the government’s claim that they had no control over the Freikorps. As a result the miners returned to work, but the majority of them had no illusions about the loyalties of the SPD or the leadership of the USPD.

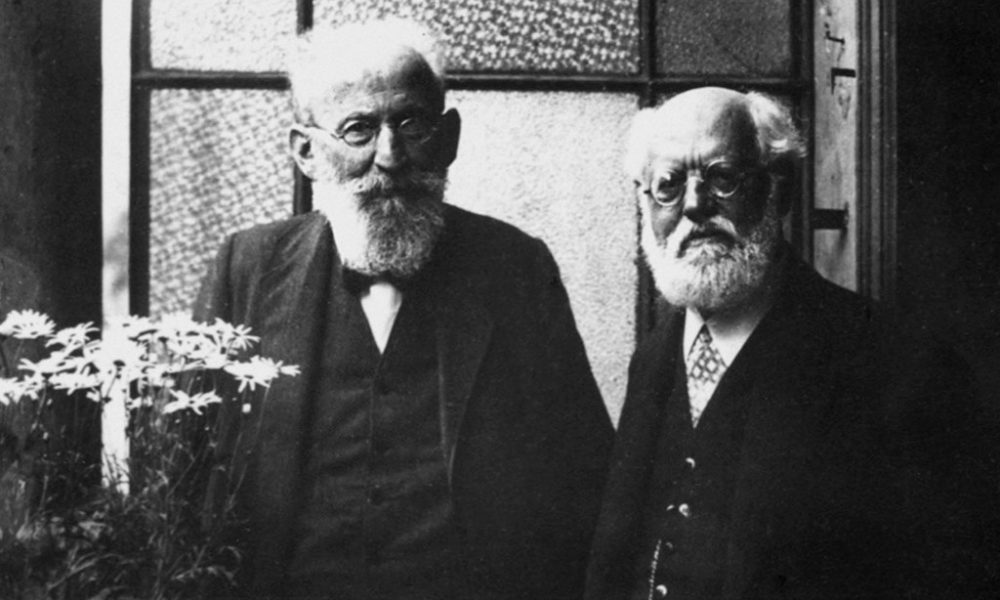

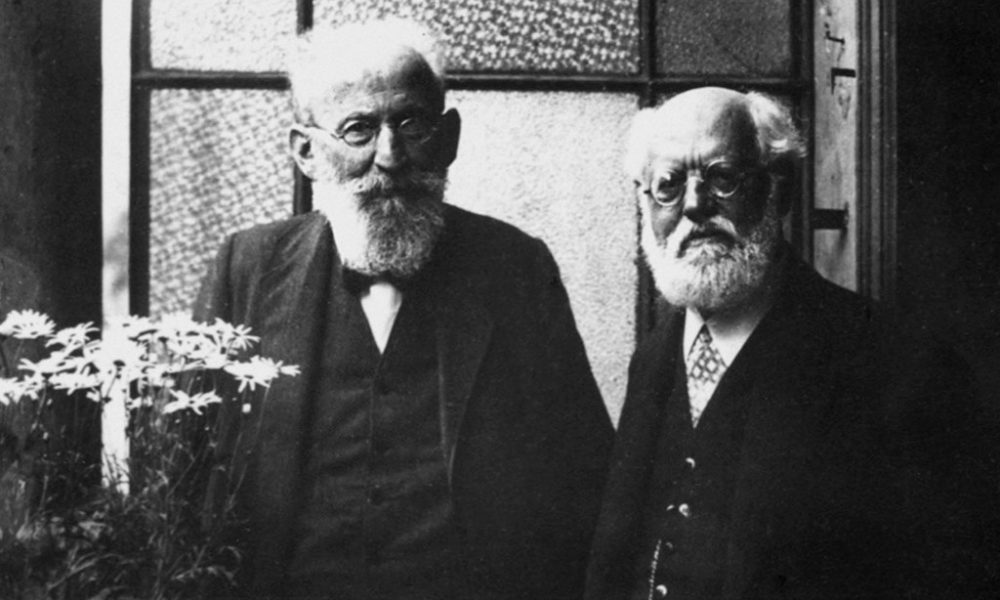

The internal debate in the USPD came to a head at a party conference held after the end of the miners’ strike. Convinced by the arguments of Emil Barth the delegates narrowly voted in favour of the party formally withdrawing from the government; Hugo Haase and Wilhelm Dittmann, the two cabinet ministers, were naturally annoyed but not surprised at the turn of events. A second vote demonstrated the USPD’s overly-optimistic view of their situation however; by a comfortable majority, the delegates voted against a formal alliance with the Communists. The right-wing leadership of the party used the vote as a justification to instruct the regional party branches to cease any alliance with the KPD. This action triggered a near-revolt; in both socialist strongholds and the rural regions where revolutionary power was precarious, local USPD branches loudly made their opposition to the directive known. Some branches defected to the KPD wholesale, while others demanded the convention of a special party congress to correct the leadership’s mistakes. Those who were on the left of the leadership, such as Emil Barth and Robert Dissmann, successfully drafted socialist veterans Karl Kautsky and Eduard Bernstein into supporting the call for a special party congress; the latter two were both opposed to the Communists, but they were dismayed at the growing disunity in the party.

Eduard Bernstein and Karl Kautsky, former stalwarts of the German (and international) left

With the resignation of Haase and Dittmann from the government, the SPD ministers were finally free to pursue a political alliance which would better suit their liberal democratic interest. The Democrats were the obvious choice, as they were already intimately involved in the government. In order to maintain the pretence of still being a party for the workers, Ebert retained the cabinet’s revolutionary name Council of People’s Deputies (Rat der Volksbeauftragten) and held back from inviting the Centre Party into the government. Hugo Preuss, who was already an important member of the Ministry of the Interior, and DDP leader Friedrich von Payer, who had been the last Vice-Chancellor before the Revolution, were appointed by Ebert to the Council. The Executive Committee of the Berlin councils, where the Communists and Independents now had a majority, were understandably angry as it were they who appointed the revolutionary cabinet in the first place. The Executive Committee had no power to enforce its will however, as the federal election had clearly given its voice to such a centrist government and military action on behalf of the Executive Committee would likely be responded to with overwhelming force. As a result, the Executive Committee organised a demonstration in protest as well as a declaration that the current government was responsible solely to the workers’ and soldiers’ councils. The demonstration in Berlin on 20th February, which attracted well over two hundred thousand workers, was left unmolested by the police; this was the opportunity Ebert had been looking for to remove Emil Eichhorn as chief of police. Eichhorn, who was still with the USPD, had sent his police officers to protect the demonstrators from any recriminations from the government or lingering Freikorps. The Prussian Ministry of the Interior once again summoned the police chief and informed him of his immediate termination. To the surprise of the government Eichhorn accepted his sacking and instead addressed the demonstrators, stating that he was proud to no longer have to serve a reactionary, repressive regime; the crowd cheered him on and proclaimed Eichhorn a hero. SPD loyalist Eugen Ernst was appointed as the new police chief.

The USPD special congress was held on 21st February, just after the demonstration in Berlin. The unity of the workers in the face of the government and Eichhorn’s triumphal arrival at the party congress made a great impression on the subsequent proceedings. 354 elected delegates from across Germany travelled to Berlin to decide the future of the party; some were elected by those who had already defected to the KPD. The central question of the congress was whether the party should cooperate with the Communists. To many of the delegates, the question was a strange one; throughout the country, Independents and Communists had been cooperating since the split. The collaboration had not always been smooth, but to many of the delegates and the members they represented they were under the impression that both parties had the same goal of a socialist republic of workers’ and soldiers’ councils. Some in the party were concerned with the news they heard from Russia and even fewer were worried that the German Communists would emulate the perceived tactics of the Bolsheviks, but they were confident that such events would not happen in Germany. Bernstein and Kautsky did their best to disabuse their colleagues of this complacent attitude, disputing the sincerity of the Bolsheviks’ commitment to socialism and warning of their corruptive influence. However, the prestige which the two veterans once held had waned in recent months as it appeared that they were out of touch with the Revolution which very clearly was occurring in Germany. Barth led the leftist counterattack and pressed Bernstein and Kautsky on their views towards the SPD government and its flirtations with the Freikorps and the right-wing parties. Kautsky condemned the SPD government but unconvincingly claimed that the Communists were just as bad, while Bernstein skirted around the question and claimed revolutionary action would just result in strengthening the reactionaries. Haase remained silent, cognisant of his central role in the party’s current distress and fearful that an intervention from himself would only worsen matters. Eichhorn joined in the criticism of the right, arguing that proletarian unity was essential at that time. A vote was finally called and cooperation with the Communists was supported by a majority of 211 delegates. Subsequently, the vote which Haase was dreading came: a leadership vote. Most of the delegates supported Eichhorn but he declined due to his age and gave his support to Barth, who was duly elected as leader.

Dramatis Personae (OTL biographies)

Robert Dissmann: A veteran trade unionist, Dissmann had unsuccessfully stood as the left's candidate for the SPD Executive in 1911 and 1913. His opposition to the war resulted in him joining the USPD upon its founding and being elected co-president of the German Metalworkers' Union in 1919. Dissmann was opposed to the USPD's entry to the Comintern and so remained with the rump of the party after the majority joined the KPD. However, alongside Paul Levi he led the attempt to prevent the USPD's reunification with SPD. Once Dissmann was back in the SPD he led the party's left wing until his death in 1926.

The day of the federal election, 16th February, was also the date of the expiration for the second extension of the armistice with the Entente. Friedrich Ebert’s government devoted all of its efforts to secure another extension, but complications arose from French demands that the Polish rebels be classified as Entente forces. Accepting would be a tacit abandonment of Posen, but the alternative was a resumption of the war. The situation was out of the government’s hands anyway: most of the Deutsches Heer soldiers were mutinying, while the Freikorps who were still fighting had been declared outlaws. The government reluctantly agreed to the French demand and gained an armistice extension of eight months. Peace was not achieved however. Shortly after the ceasefire was signed the Freikorps began a southern offensive against Gostyn and Kosten, threatening Posen. Once those two towns were back under German control, the Freikorps decided to push on towards Posen from the south. Joseph Noulens, chairman of Poland’s Entente mission, unilaterally decided to retaliate and ordered a joint Franco-Polish army across the border to attack Ostrów. The Freikorps cancelled their offensive against Posen and diverted troops to defend Ostrów. A tough battle ensued, causing much damage to a city that had so far avoided a lot of the insurrection’s violence, and the Franco-Polish forces emerged victorious on 18th February. The government tried to downplay the escalation of the Polish rebellion by pointing to their success in negotiating a ceasefire and arguing that as such the strikers’ demand had been met. After twelve days of continuous striking the miners of the Ruhr and central Germany had been feeling the pinch of not working; the strike funds of the unions and donations from the local branches of the KPD and USPD were beginning to run out. Additionally the miners were convinced by the government’s claim that they had no control over the Freikorps. As a result the miners returned to work, but the majority of them had no illusions about the loyalties of the SPD or the leadership of the USPD.

The internal debate in the USPD came to a head at a party conference held after the end of the miners’ strike. Convinced by the arguments of Emil Barth the delegates narrowly voted in favour of the party formally withdrawing from the government; Hugo Haase and Wilhelm Dittmann, the two cabinet ministers, were naturally annoyed but not surprised at the turn of events. A second vote demonstrated the USPD’s overly-optimistic view of their situation however; by a comfortable majority, the delegates voted against a formal alliance with the Communists. The right-wing leadership of the party used the vote as a justification to instruct the regional party branches to cease any alliance with the KPD. This action triggered a near-revolt; in both socialist strongholds and the rural regions where revolutionary power was precarious, local USPD branches loudly made their opposition to the directive known. Some branches defected to the KPD wholesale, while others demanded the convention of a special party congress to correct the leadership’s mistakes. Those who were on the left of the leadership, such as Emil Barth and Robert Dissmann, successfully drafted socialist veterans Karl Kautsky and Eduard Bernstein into supporting the call for a special party congress; the latter two were both opposed to the Communists, but they were dismayed at the growing disunity in the party.

Eduard Bernstein and Karl Kautsky, former stalwarts of the German (and international) left

With the resignation of Haase and Dittmann from the government, the SPD ministers were finally free to pursue a political alliance which would better suit their liberal democratic interest. The Democrats were the obvious choice, as they were already intimately involved in the government. In order to maintain the pretence of still being a party for the workers, Ebert retained the cabinet’s revolutionary name Council of People’s Deputies (Rat der Volksbeauftragten) and held back from inviting the Centre Party into the government. Hugo Preuss, who was already an important member of the Ministry of the Interior, and DDP leader Friedrich von Payer, who had been the last Vice-Chancellor before the Revolution, were appointed by Ebert to the Council. The Executive Committee of the Berlin councils, where the Communists and Independents now had a majority, were understandably angry as it were they who appointed the revolutionary cabinet in the first place. The Executive Committee had no power to enforce its will however, as the federal election had clearly given its voice to such a centrist government and military action on behalf of the Executive Committee would likely be responded to with overwhelming force. As a result, the Executive Committee organised a demonstration in protest as well as a declaration that the current government was responsible solely to the workers’ and soldiers’ councils. The demonstration in Berlin on 20th February, which attracted well over two hundred thousand workers, was left unmolested by the police; this was the opportunity Ebert had been looking for to remove Emil Eichhorn as chief of police. Eichhorn, who was still with the USPD, had sent his police officers to protect the demonstrators from any recriminations from the government or lingering Freikorps. The Prussian Ministry of the Interior once again summoned the police chief and informed him of his immediate termination. To the surprise of the government Eichhorn accepted his sacking and instead addressed the demonstrators, stating that he was proud to no longer have to serve a reactionary, repressive regime; the crowd cheered him on and proclaimed Eichhorn a hero. SPD loyalist Eugen Ernst was appointed as the new police chief.

The USPD special congress was held on 21st February, just after the demonstration in Berlin. The unity of the workers in the face of the government and Eichhorn’s triumphal arrival at the party congress made a great impression on the subsequent proceedings. 354 elected delegates from across Germany travelled to Berlin to decide the future of the party; some were elected by those who had already defected to the KPD. The central question of the congress was whether the party should cooperate with the Communists. To many of the delegates, the question was a strange one; throughout the country, Independents and Communists had been cooperating since the split. The collaboration had not always been smooth, but to many of the delegates and the members they represented they were under the impression that both parties had the same goal of a socialist republic of workers’ and soldiers’ councils. Some in the party were concerned with the news they heard from Russia and even fewer were worried that the German Communists would emulate the perceived tactics of the Bolsheviks, but they were confident that such events would not happen in Germany. Bernstein and Kautsky did their best to disabuse their colleagues of this complacent attitude, disputing the sincerity of the Bolsheviks’ commitment to socialism and warning of their corruptive influence. However, the prestige which the two veterans once held had waned in recent months as it appeared that they were out of touch with the Revolution which very clearly was occurring in Germany. Barth led the leftist counterattack and pressed Bernstein and Kautsky on their views towards the SPD government and its flirtations with the Freikorps and the right-wing parties. Kautsky condemned the SPD government but unconvincingly claimed that the Communists were just as bad, while Bernstein skirted around the question and claimed revolutionary action would just result in strengthening the reactionaries. Haase remained silent, cognisant of his central role in the party’s current distress and fearful that an intervention from himself would only worsen matters. Eichhorn joined in the criticism of the right, arguing that proletarian unity was essential at that time. A vote was finally called and cooperation with the Communists was supported by a majority of 211 delegates. Subsequently, the vote which Haase was dreading came: a leadership vote. Most of the delegates supported Eichhorn but he declined due to his age and gave his support to Barth, who was duly elected as leader.

Dramatis Personae (OTL biographies)

Robert Dissmann: A veteran trade unionist, Dissmann had unsuccessfully stood as the left's candidate for the SPD Executive in 1911 and 1913. His opposition to the war resulted in him joining the USPD upon its founding and being elected co-president of the German Metalworkers' Union in 1919. Dissmann was opposed to the USPD's entry to the Comintern and so remained with the rump of the party after the majority joined the KPD. However, alongside Paul Levi he led the attempt to prevent the USPD's reunification with SPD. Once Dissmann was back in the SPD he led the party's left wing until his death in 1926.

Last edited:

The house of cards to falling down. Soon.

I wonder what will end up sparking the revolution?

I wonder what will end up sparking the revolution?

me. I will.I wonder what will end up sparking the revolution?

Threadmarks

View all 42 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Pseudo-Teaser for Soviet Russia 2 Pseudo-Teaser for Africa 1 Peace in the Balkans? Pseudo-Teaser for Africa 2 The White Counteroffensive 'Techno-thriller novel' Chapter 1 The Beginning of the End Part 1 Constitution of the Free Socialist Republic of Germany

Share: