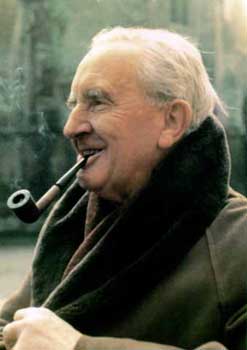

J.R.R. Tolkien (1892-1992)

Our article today looks at Tolkien's final two decades, from the health scare of August 1973, to his peaceful death in May 1992.

An Old Man in a Hurry (1973-1978)

Tolkien's life was one marked by turning points, none more so than his narrow brush with death in August 1973, when he underwent treatment for a perforated stomach ulcer. The author benefited from a prompt diagnosis; a week later, and the resulting infection may have killed him.

Bedridden for weeks after the operation, recovery was slow. Tolkien took the opportunity to jot down some renewed plans for his Silmarillion mythos, together with further ideas for Middle-earth essays (Comments on Noldorin Heraldry was composed entirely during this period). His daughter Priscilla, who visited him in hospital, noted that Tolkien seemed to possess a new energy, as though he felt he could not leave his life's work unfinished. It is interesting to consider that the next five years saw Tolkien pursue The Silmarillion with an enthusiasm bordering on desperation, yet all this work only took him further from his goal: rather than one unfinished version of his mythos, he ended up with two.

His mid-1970s work gave effect to some of his more radical ideas of the 1960s: gone was the mythical Tale of the Sun and Moon, and the notion that Arda was in origin flat. Rather, the Sun and Moon were created at the same time as the Earth, and the world was round to begin with. Orcs were no longer derived from Elves, but from Men, and Elvish paranoia led to attempted genocide when the two races met. Galadriel, already being 'whitewashed' into a Virgin Mary figure as of late 1972, was further rewritten to deal with this: she plays a key role in persuading the Eldar that not all Men are evil.

The opinions of Tolkien fans on these changes remain mixed. Some prefer the older, more mythic versions, and argue that since the updated material was never published - Three Tales can be read either way - it is non-canonical. Others argue that since we are no longer dealing with outlines, but rather completed stories, we must accept Tolkien's final verdict on the matter. This latter group also point to his explicit commentary in the posthumous Letters and Essays (1995). Only the BBC's 2005 attempt to adapt The Lord of the Rings to television has sparked more fandom controversy.

In addition to building off the 1960s material, this period also saw Tolkien revisit places he had not touched in over half a century. The Voyage of Eärendil, included in Three Tales, was turned from mere outline into a complete story of novella length during the summer of 1975 - though the hero's encounter with Ungoliant has attracted criticism that it is too similar to Sam Gamgee's defeat of Shelob. Voyage is also filled with more religious imagery than other Middle-earth stories, to the point where one commentator has called it Tolkien's grail quest. Then there is the attempted 1976 rewrite of The Fall of Gondolin, which cuts off at the beginning of the battle - thereby forcing its eventual exclusion from Three Tales. When asked about this in a 2007 BBC interview, Christopher Tolkien explained that the problem was the Balrogs: his father struggled to portray a creature on the scale of Durin's Bane that would fit with the necessities of the Tale. Even the author living to be a hundred could not help.

This last great burst of activity petered out in March 1978, as the 86 year old Tolkien suddenly found himself sidetracked by a vicious legal battle...