257. Looking for a war

General Boum (Commander-in-Chief): “Silence when you're speaking to an officer!…

My plan is simple. Your Highness must bear in mind

that the whole art of war is summed up in two words

- surprise and circumvention….

My forces, thus distributed,

will proceed by three different routes to one central point,

where I have decided to concentrate them…

I don't care where the enemy are, but what I do know is -

that I shall annihilate them!”

Jacques Offenbach, Halévy, Ludovic, Meilhac, Henri, “Grande Duchesse Gerolstein”

"C'est tout-à-fait ça!" (That's exactly how it is!)

Bismarck after watching performance of “Grande Duchesse…”

“You are the only SOB here who knows what he wants.”

Patton

Prussia. Bismarck in charge. 1865 - early 1866.

As the PM of Prussia Bismarck had a pretty clear idea on what he wanted. He wanted unification of the Northern (Protestant) German states under the tight Prussian control. Unlike the HRE arrangements, his “dream state” was going to be closely united by having the one parliament and effective central (Prussian) government. The member states would be divided into two categories. The bigger ones will preserve certain autonomy with their own titular rulers, parliaments and armies but their functions are going to be limited to the local issues and the armed forces are going to be under control of the central Ministry of War. The small ones are going to be directly absorbed into Kingdom of Prussia with the present rulers preserving their titles and possessions and perhaps getting some pensions.

So far, number of the enthusiasts was limited to very few.

German Allies.

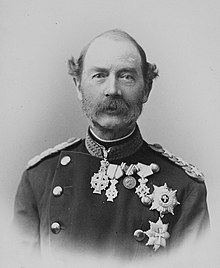

The most prominent was the

Grand Duchy of Mecklenburg: for all practical purposes it was pretty much surrounded by the Prussian territories and, due to the fact that the Grand Duchy was rather poor and backward, its rulers had been routinely having a second job (and source of income) serving on the high positions in Prussian Army. The current one, Frederick Francis II, had been linked to both Hohenzollerns and Romanovs ( maternal first cousin of both Prussian Crown Prince

Frederick and

Russian Tsar Alexander II) and served in Prussian army, presently in the staff of

Generalfeldmarschall Friedrich Graf von Wrangel, so that he was going to get the best deal possible.

Then there was the

Duchy of Brunswick the duke of which, William III, left most government business to his ministers, and spent most of his time outside of his state at his possessions in

Oels, in Prussian Silesia. Quite clearly, the best way for him to retain his private possessions and to get a good deal for his duchy was to side with Prussia. Not that this duchy possessed any military force worth mentioning.

Grand Duchy of Oldenburg. The Grand Duke, Peter II, had close ties to the Russian imperial family (there was the whole branch of the Russian Oldenburgs) and on good terms with the Hohenzollerns. In the military terms his duchy with population of 800,000 was not a serious factor but geographically the Grand Duchy was important for the overall Bismarck’s plan of unification.

Then, there were minor principalities mostly squeezed between Prussia and Saxony or already surrounded by the Prussian territories: Anhalt, Saxe Coburg & Cotha, Saxe-Aattenburg, Schwarzburg-Sondershausen, Waldeck, Lippe. Sum total of their

military importance was zero.

The free cities of Lubeck, Bremen and Hamburg also were on the Prussian side expecting trade increases in the case of united Northern Germany.

International situation.

Russia was sympathetic to Bismarck’s plans. Alexander II insisted only that his relative, the Grand Duke of Hesse, should not suffer too much during the redegiance of Germany, and Bismarck could easily satisfy this policy of family feelings. It was promised that all necessary efforts will be made to prevent the Polish intervention on Austrian side in the case of war.

Britain also was busy with its internal and colonial affairs and experienced a period of reduced interest in European politics.

France was not against Bismarck’s plans and, anyway, King Oscar was getting old, his health was failing and his main attention was to secure a safe succession for his son by improving the domestic situation in France. The unnecessary war definitely was not on his agenda. But he could and did help to negotiate alliance with Italy.

Italy. King Victor-Emmanuel wanted three things:

- Get Venice from Austria

- Get the whole Italy

- To show that his army and navy are not a laughingstock most of Europe considered them to be. Which meant that he would be inclined to join a war against Austria.

Hungary was not quite ready for a big war. King Szilard I ceded most of his powers to the Diet and his subjects were more interested in improving their own well-being than in the military adventures. Its top general and Minister of War, Artúr Görgei, was, of course, a national hero but his arguments in favor of a big modern army were not completely successful and his own achievements of 1848-49 had been used as a counter-argument: why burden state with a big standing army when it was proven that in the case of need the people would rise in defense of the fatherland and defeat the professional armies of the invaders? Some kind of a compromise had been reached almost along the old Prussian lines: a relatively small regular army with 6 years term of service and a bigger land militia passing through some kind of a military training.

Then, there was an ongoing low-level trouble in Transylvania where the Hapsburg agents kept spreading pro-Hapsburg agitation among the Rumanian population. It was not fully successful but had been getting certain traction and there was a need to maintain certain military presence in the region. So, realistically, it could be expected that in the best case scenario Hungary would be able to post 50-60,000 troops on the border forcing Austrians to keep comparable numbers on their side of the Leithe River to protect Vienna.

Domestically. Bismarck thus succeeded in the political preparation of the war outside Germany. In domestic politics, the situation was worse. Since the military reform of 1860, the Prussian government has been in a cruel quarrel with the Prussian Landtag, who refused to approve the budget annually, and led the state against the wishes of the vast liberal majority of the Prussian bourgeoisie. Opposition to Bismarck's government was almost on the verge of revolution; the government had a reputation as rotten reactionaries; the masses of the people were far from its support. Only rare, most insightful representatives of the Prussian bourgeoisie, watching Bismarck's firm hand, began to understand that they were facing the person who is able to unite Germany and realize the dream of the German bourgeoisie. Bismarck attached great importance to the preparation for war in domestic political terms and decided to wage war under the broad slogan of the North German union. The slogan increased popularity of his rule in Prussia but, as was already mentioned, pushed most of the HRE states into the Austrian camp. In the coming war, Prussia had to meet extra 4 corps of hostile troops, however, of poor quality, mobilized for a long time, not united by a common command. But the war was put in the plane of struggle for a great slogan, not a fratricidal massacre for dynastic interests - the increase in the territory of Prussia at the expense of other members of the HRE. Still, the general attitudes in Prussia were rather lukewarm. Which meant that Bismarck had to convince Prussian population that the war he was planning is actually a defensive war. And for this he needed to create a plausible cause.

Creating a plausible cause.

The Duchy of Saxe-Lauenburg existed from 1296 and, starting at least from the early XVIII, it was usually serving as spare change in various international territorial readjustments. Between the LNW of 1700-04 and 1866 it managed to belong (sometimes more than once) to pretty much each and every regional power: Sweden, Hanover, Denmark, Prussia. In 1815-64 it was ruled by the Kings of Denmark (Kings of Denmark-Norway, Great Dukes of Gottorp from Oldenburg House) on terms of the personal union. Unlike all other components of the Oldenburg possessions, the Duchy was never fully integrated and retained a completely independent administration. Its population was completely German and in 1848-49 there was an attempt of a separatist uprising under umbrella of a popular idea of “unification of the German nation”. The leaders of the uprising had been counting upon military help from Frankfurt Parliament but it did not materialized. FWIV of Prussia sent a small force, which was easily repelled by the Danish troops and the leaders of uprising fled from the duchy.

However, in 1863 situation changed. The main line of the Oldenburg dynasty became extinct and their territories were inherited by theGlücksburg line. This resulted in a dynastic crisis because the German population of the duchy supported the

House of Augustenburg, a cadet and strictly German branch of the Danish royal family. Things became worse when in 1864 Christian IX signed a constitution which was going to integrate the duchy with the rest of the state. This was considered within the HRE as a gross violation of the previous international agreements and in 1864 Austria and Prussia (and the rest of the HRE) were threatening Denmark with a war.

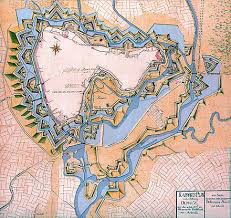

Taking into an account a minuscule importance of the duchy for “Denmark”, Christian was willing to negotiate and arranged selling of the duchy into a joined possession of Austria and Prussia for £300,000. These money he was planning to spend on improvement of the waterways: the Elder Canal built in the late XVIII century (blue on the map) was too narrow and shallow for the modern needs allowing passage of the ships under 300 tons and a bigger one was needed (yellow on the map). All the Powers (with the understandable exception of Prussia) involved in Baltic trade had been supporting this idea: a bigger canal

was needed and neither Britain nor Russia wanted it to be controlled by a Great Power.

So, in a rare unison, they applied the diplomatic pressure and in 1865 the deal passed through. Denmark started construction of a new canal and the Duchy got Austrian and Prussian governors who were expected to administer it together.

The crisis starts.

As a byproduct this agreement provided Bismarck with a perfect scenario for making Austria an aggressor. Due to the obvious geographic reasons Austria could not accomplish annexation of the Duchy and, as a result, was supporting scenario of making it an independent member of the HRE ruled by a duke from

Augustenburg House while Prussia wanted to incorporate it as one of her provinces. The crisis started on 26 January 1866, when Prussia protested the decision of the Austrian Governor of the Duchy to permit its estates to call up a united assembly and to allow agitation in

Augustenburg’s favor, declaring the Austrian decision as a breach of the principle of joint sovereignty. Austria replied on 7 February, asserting that its decision did not infringe on Prussia's rights in the Duchy. In March 1866, Austria reinforced its troops along its frontier with Prussia. To this “obvious act of aggression” Prussia responded with a partial mobilization of five divisions on 28 March.

Bismarck made an alliance with Italy on 8 April, committing it to the war if Prussia entered one against Austria within three months, which was an obvious incentive for Bismarck to go to war with Austria within three months so that Italy would divert Austrian strength away from Prussia. Austria responded with a mobilization of its Southern Army on the Italian border on 21 April. Italy called for a general mobilization on 26 April and Austria ordered its own general mobilization the next day.

[6] Prussia's general mobilization orders were signed in steps on 3, 5, 7, 8, 10 and 12 May.

When Austria brought the dispute before the German Diet on 1 June and also decided on 5 June to convene the Diet of Saxe-Lauenburg on 11 June, Prussia declared that the

Gastein Convention of 14 August 1865 had thereby been nullified and invaded the Duchy on 9 June. When the German Diet responded by voting for a partial mobilization against Prussia on 14 June, Bismarck claimed that the Prussian membership in the HRE had ended.

Comic relief.

In February 1866 Victor-Emannuel made Austria a proposal to buy Veneto for 1,000,000 lira but the offer was rejected and Italy made an alliance with Prussia. Now FJI re-though the offer and asked Emperor Oscar to act as an intermediary: Veneto will be passed to France so that France will give it to Italy as a present. [1]

Now V-E could get what he wanted without a fight but he felt bound by his alliance to Prussia, there was a full-scale mobilization and military hysteria in Italy with everybody itching to fight the hated enemy again. So he declared war on Austria anyway.

Of course, it would be wiser for Austria to go down to direct negotiations with Italy, or at least evacuate its Italian possessions before the outbreak of hostilities, than to spend 80,000 good field troops and almost the same number of secondary fortresses in the garrisons to defend the province, which was already cut off from the state. But this did not happen.

In practical terms, with the Austrian main port being now Trieste, the Veneto region was not strategically important anymore.

Getting ready. Prussia and Austria. To push Austrians further to a full mobilization, Bismarck leaked a fake Prussian plan of the campaign which involved immediate Prussian attack without a complete mobilization and declaration of war. In the deep world, unmobilized Prussian troops were to break into the allied fortress of Mainz and disarm the Austrian and Allied troops that made up its garrison. At the same time, on the first day of mobilization, Prussian troops had to break into Saxony from different sides, take unmobilized Saxon troops by surprise in their barracks and, only after ending them, begin mobilization; having finished the latter, two armies - 193,000 and 54,000 - had to invade Bohemia and defeat the Austrian armies before they have time to assemble. [2]

As soon as rumors of a possible sudden Prussian attack reached Vienna, a marshal's council was assembled in Vienna in the first half of March - a meeting of representatives of the highest military power in the capital, reinforced by corps commanders and outstanding generals invited from the provinces. The Marshal Council began discussing the campaign plan and decided, first of all, to strengthen the I Corps located in Bohemia by 6,700 men in order to bring it to full peacetime strength.

This was all that Bismarck needed. His press greatly inflated the strengthening of Austrian troops in Bohemia; on March 28, Prussia began to strengthen the battalions of 5 divisions located near the Saxon and Austrian borders, from 530 people per 685 people. Subsequently, horses for field artillery followed. Austria was forced to react to the new events. To hide them, Austrian censorship forbade newspapers to print any information about the movement of troops or the strengthening of their composition. Bismarck also used this circumstance by inviting the Prussian press to place verified data on changes in the deployment and composition of Prussian troops and sketching a shadow of preparation for the war on Austria. On April 27, Austria announced a general mobilization.

The Prussian king still resisted the mobilization of the Prussian army. Only sequentially, on May 3, 5 and 12, Roon and Bismarck snatched mobilization decrees from him, which in three steps covered the entire Prussian army. Thus, Bismarck preferred to abandon the benefits of the speed of Prussian mobilization in the war of 1866 in order not to assume the odiousness of the beginning of the war and not to put Prussia in an unfavorable political position. Politics has subjugate the strategy.

Austria did not want war, and, as always in such cases, believed that it would not come to war; Austria did not conduct systematic political preparation for the war. Contrary to Franz Joseph, most Austrian generals were convinced of the superiority of Prussian weapons and Prussian troops. The assistance of the middle and small German states was not regarded too high. So far the only achievement of Austrian policy was to attract most of the German Union states, frightened by the Bismarck program, which deprived them of sovereignty. These German allies of Austria had a war time armies totaling 142,000. However, while Italy, Austria and Prussia started arming in April, the troops of the Austrian German allies remained unmobilized.

Only on June 14, at the request of Austria, the Imperial Diet (Council of the HRE in Frankfurt am Main) decided to mobilize four corps - a contingent of the Imperial Army raised by medium and small states. But this decision to mobilize has already been taken by Prussia as a declaration of war. Hostilities between the mobilized Prussians and the unmobilized allies of Austria began the next day, June 15. Only Saxon troops were ready in advance and withdrew from Saxony, where the Prussians invaded, to Bohemia to meet the Austrian army. The most valuable thing Austria received from its allies was thus the 23,000-strong Saxon Corps.

Austrian plans.

The Chief of the Austrian General Staff, Baron Genikstein, a rich aristocratic man, least thought about the issues of strategy and operational art. Archduke Albert, son of Archduke Charles, the most prominent candidate of the dynasty to command the troops, hurried to get a calm Italian front on the pretext that it is impossible to put the reputation of the dynasty at risk of defeat.

General Benedek, an excellent field officer who commanded the Italian army in peacetime and had a deep knowledge of Lombardy, but was completely unprepared for leadership of the large masses and unfamiliar with the conditions of the Austro-Prussian front, was nominated to the Bohemian theater, against his desire; at the same time, Archduke Albrecht did not allow Benedek to take with him his Chief of Staff, General Ion, who was most capable of dealing with the major issues of all officers of the Austrian General Staff.

When, in view of the threat of war, in March 1866, a plan of operations against Prussia was required from the Chief of the Austrian General Staff, Baron Henikstein, the latter proposed to draw up one to Colonel Nieber, a professor of strategy of the military academy. The latter said that for this work he needed data on the mobilization readiness of the Austrian army. The Ministry of War provided Neiber with an extremely pessimistic assessment of the condition of the Austrian troops; only after a few months could the army become quite combat-ready. Therefore, Neiber spoke in favor of the Austrian army to gather in a defensive position near the fortress of Olmütz before the operations and enter Bohemia, threatened by the Prussians on both sides, only after gaining sufficient combat capability.

Then, under the patronage of Archduke Albert, Neiber's predecessor in the Department of Strategy, General Krismanich, was appointed Chief of Operations of the Bohemian Army.

He was a connoisseur of the Seven Years' War and believed that in a hundred years the picture of Down and Lassi's operations against Frederick the Great would be repeated. Krismanich edited the military-geographical description of Bohemia and studied all sorts of positions that existed at the Bohemian theater.

Krismanich retained Neiber's idea of the preliminary concentration of the Austrians in the fortified camp near Olmütz, with the exception of the I Bohemian Corps, which remained in the vanguard, in Bohemia, to take over the retreat of the Saxons. All 8 corps, 3 cavalry divisions and an artillery reserve destined to operate in Bohemia were to represent one army. Krismanich refused to attack Silesia, as he did not see favorable "positions" for the battle in this direction. Disregarding the railways, Krismanich expected the concentration of all Prussian forces in Silesia and their direct movement to Vienna. As a separate option, the movement of the Austrian army on three roads from Olmütz to the area of the right bank of the Elbe was developed.

In Austria, secret maps were still published with black semicircles - "positions" emphasized on them. Krismanich's plan presented a mixture from memories of the struggle against Frederick the Great, from several principles of the military art of the early XIX century, several principles of Clausewitz (Austria pursues a negative political goal, why it should conduct defensive actions accordingly) and a detailed depiction of all kinds of defensive lines, borders and positions. His plan was impressive, it was difficult to read, reported by Krismanich unusually self-confidently; Krismanich impressed with his optimism and professorial appeal of judgments. Not surprisingly, the poorly educated Austrian generals were overwhelmed by the confidence and academicism that Krismanich deployed - generally a lazy, superficial and limited person; but for us it is a mystery as it could. Kristmanich's plan can be considered an exemplary 40 years later in strategy textbooks.

Undoubtedly, if the Austrians divided their forces into two armies and chose two different areas, such as Prague and Olmütz, to concentrate them, they could make much better use of railways, rather complete deployment, would not deprive troops and retain much greater maneuverability. But for this, they had to take in military art the step forward that remained so far incomprehensible to the military theorists.

Italy fielded 165,000 field troops. The Prussian military commissioner, General Bernhardi, and the Prussian envoy persuaded the Italian command to vigorously start operations: to transfer the bulk of troops through the lower course of the river Po and march it forward to Padua, to the deep rear of the Austrian army concentrated in the quadrilateral of fortresses (Mantuya, Peschiera, Verona, Legnago), which would lead to a battle with the inverted front; then launch an energetic offensive in the inner regions of Austria - on Vienna. Of course, Italy, whose interests were ensured even before the outbreak of hostilities, was not inclining to follow these advices, and the Austrians could limit themselves to a minimum of forces on the Italian front from the very beginning of the war; however, the strategy on both sides did not fully use the benefits of Austria's political retreat from Italy.

Intermission. “The curse of concentration”.

Available experience of the previous wars had been saying that strategic deployment on a wide front carries with itself a risk of being defeated piecemeal and, as such has to be avoided by all means possible. Even the text book Bonaparte’s operations during the Great Polish War of 1805-06 had been pointing to this direction, including a precarious final battle which

almost turned into a disaster because one of his armies was late to join the main force. The fundamental changes happening since then were mostly ignored as insignificant comparing to the “fundamental laws of a war”. Besides the higher professional level of the staff officers who, unlike the Bonaparte’s time, had been getting a professional education, now during the campaign, telegraph wires were stretching behind the headquarters, allowing commander to monitor the actions of troops scattered over hundreds of miles and coordinate them with the same convenience as if they were removed from the commander for the normal mileage of an aid’s horse ride.

The separation of forces was recommended in the second half of the XIX century also by the depth of marching columns, which has increased since the start of the century, due to the increase in the numbers of troops, artillery, parks and supply trains. Also, the wide dirt roads of the XVIII with proliferation of railroads gave way to the narrower paved roads limited on both sides by the fences and ditches and preventing marching in the wide platoon columns. The number of the “wheels” of all types moving with the columns greatly increased and the humongous columns had been suffering all kinds of problems on a march.

Krismanich, who tried in 1866 to resurrect the “historic” way of action along the inner lines and moved the Austrian army (6 corps) from the vicinity of Olmütz to the upper Elbe, concentratedly, on 3 roads, caused enormous hardships for the troops, as a 120-mile long column of 4 corps and two cavalry divisions crowded on one road; the troops walked through rich Bohemia, as in the desert - even wells along the way were drawn to the bottom.

The same goes for the “classic” method of amassing before a battle powerful reserve which was going to be gradually deployed during a battle. Hence, with significantly longer battle fronts, difficulties in the flank coverage and natural gravitation to the frontal blow-breakthrough of the enemy center.

If on the eve of the battle such concentration really takes place, then a blow to the enemy from two crossing directions, which has the greatest chance of success, can be achieved only through a new, time- and effor-consuming, dangerous flank march in front of the enemy front, in order to divide your own troops into two masses.

Now, if somebody is under impression that sticking to the old cliches and being incompetent was plaguing only the Austrian army, don’t be too optimistic. 😜

_____________

[1] As I understand (and I may be wrong) by that time it would be just a free gift.

[2] In OTL this was Moltke’s proposal made in 1865, which was not realistic in 1866 by the reasons of domestic politics and generally negative attitude to the war. Launching unprovoked war in a violation of all international norms could easily turn mobilization into a revolution against unpopular Bismarck’s government. But as a tool of provocation it did work well.