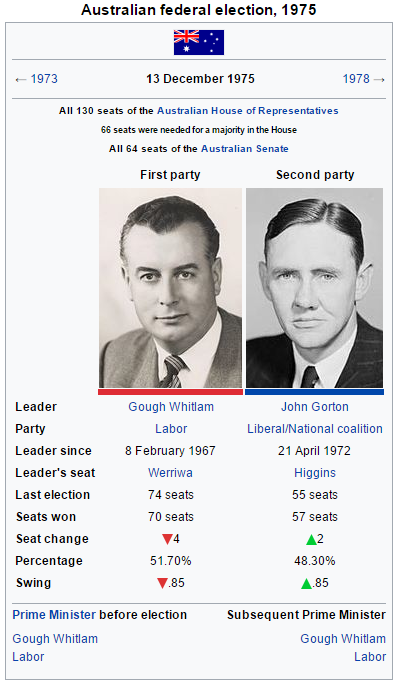

Having returned to power following a nonconsecutive two year term, Prime Minister Gough Whitlam sat on a caucus ready to enact its left-wing policies after being largely stymied before by a much smaller majority. First to be tackled was healthcare. The Medibank system of government health insurance, modeled after the American Amcare proposals, met massive contention from the right-wing Liberal/National Coalition but was much easier to stomach by moderate Labor MPs than single-payer. It passed after an arduous year of negotiations with a skeptical Senate, dominated by crossbenchers, and served as a massive legislative victory for Whitlam. It led to his victory in the upcoming general election against opposition leader John Gorton with a small swing against him.

Gorton’s loss against a government weakened by rising oil prices, increased unemployment, and out of control inflation hurt his standing among the parliamentary Liberal caucus. One of the key bases of support he could count on was the rural-populist National Party – which was nominally led by the Premier of Queensland, Joh Bjelke-Petersen, their most successful member though the leadership was a more informal role – and they couldn’t vote in the Liberal Party elections. Tensions reached a boiling point in September 1976, where opponents of Gorton managed to force a spill. The opposition leader was deposed in a short vote in favor of moderate Shadow Treasurer and Snedden Ministry rival Don Chipp. The Coalition frontbench was reorganized, the populists out and the more socially liberal/liberty conservative faction taking the reins. Joh Bjelke-Petersen, no fan of Chipp, nearly caused the Queensland Nationals to break from the Coalition but was convinced not to by Nationals Leader Doug Anthony and Gorton himself. Nevertheless, the divisions in the Coalition wouldn’t be easy to repair for Chipp.

Gorton’s loss against a government weakened by rising oil prices, increased unemployment, and out of control inflation hurt his standing among the parliamentary Liberal caucus. One of the key bases of support he could count on was the rural-populist National Party – which was nominally led by the Premier of Queensland, Joh Bjelke-Petersen, their most successful member though the leadership was a more informal role – and they couldn’t vote in the Liberal Party elections. Tensions reached a boiling point in September 1976, where opponents of Gorton managed to force a spill. The opposition leader was deposed in a short vote in favor of moderate Shadow Treasurer and Snedden Ministry rival Don Chipp. The Coalition frontbench was reorganized, the populists out and the more socially liberal/liberty conservative faction taking the reins. Joh Bjelke-Petersen, no fan of Chipp, nearly caused the Queensland Nationals to break from the Coalition but was convinced not to by Nationals Leader Doug Anthony and Gorton himself. Nevertheless, the divisions in the Coalition wouldn’t be easy to repair for Chipp.

With a much friendlier Senate, Whitlam had freer rein to pass his agenda. Papua New Guinea was admitted as a state with equal representation to the rest of Australia, resulting in three new seats proportioned for it during the next general election and serving as a big win for Whitlam’s election promises. The effects of the oil crisis had largely disappeared, and an uptick in economic growth by 1977 largely ended the inflationary crises that plagued Snedden and the Second Whitlam Ministry. The Government used this to shore up the Medibank program, which proved popular with the Australian public.

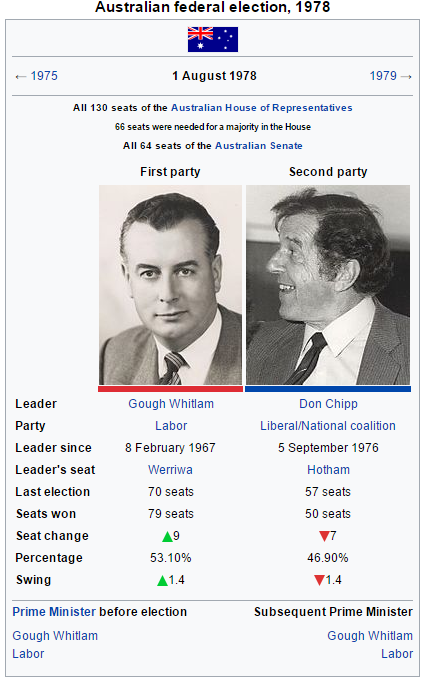

The majority of the summer months of 1978 were occupied with the debate over the national anthem. Feeling that “God Save the King” was a bit anachronistic, Whitlam proposed that it be changed to something more Australian in nature. Monarchists opposed, but Liberal leader Chipp was also in favor of the proposal so the backlash was neutralized largely at both parties. What would end up the contentious battle was what the new anthem would be. Chipp favored the bland and more traditional “Advance Australia Fair” while Whitlam, in a move that would surprise many, backed the famous bush ballad “Waltzing Matilda.” With Parliament evenly divided on this and his capital gains tax proposal, the Prime Minister called an election for August to obtain a mandate.

In his fourth election victory, Gough Whitlam procured his mandate. Voters who were skeptical of new taxes nevertheless trusted Whitlam’s judgement, Coalition economic arguments against capital gains taxes not persuasive in the marginal “Mortgage Belt” seats that decided the election – the tax would mostly fall on the rich, which was the centerpiece of the Labor campaign. Additionally, Labor performed its best result in rural Australia in a generation. Rural voters flocked to Whitlam for his backing of Waltzing Matilda as the national anthem, picking off seven of their net gain of nine seats in the Outback and rural east (including the seat of Lyons in central Tasmania, the state a Coalition stronghold since 1969). Both Independent Papuan MP’s were defeated, the Coalition gaining Port Moresby while Labor acquired the two rural seats. Chipp, facing the Coalition’s worst showing of the post-war era in his first election, barely survived a challenge on his right as Whitlam put together his Fourth Ministry.

In his fourth election victory, Gough Whitlam procured his mandate. Voters who were skeptical of new taxes nevertheless trusted Whitlam’s judgement, Coalition economic arguments against capital gains taxes not persuasive in the marginal “Mortgage Belt” seats that decided the election – the tax would mostly fall on the rich, which was the centerpiece of the Labor campaign. Additionally, Labor performed its best result in rural Australia in a generation. Rural voters flocked to Whitlam for his backing of Waltzing Matilda as the national anthem, picking off seven of their net gain of nine seats in the Outback and rural east (including the seat of Lyons in central Tasmania, the state a Coalition stronghold since 1969). Both Independent Papuan MP’s were defeated, the Coalition gaining Port Moresby while Labor acquired the two rural seats. Chipp, facing the Coalition’s worst showing of the post-war era in his first election, barely survived a challenge on his right as Whitlam put together his Fourth Ministry.

No discussion of the Australian Labor Party of the 1970s and 1980s could be made without a rather sizable portion of it devoted to Robert “Bob” Hawke. A minister’s son, his family was quite well connected in the federal Labor Party – his uncle being the Labor Premier of Western Australia. Joining the Australian Council of Trade Unions after receiving his law degree, Hawke rose through the ranks rather quickly and was elected President of the ACTU on a reformist platform (rumor was that several communist-leaning elements supported his candidacy).

Hawke blazed a pragmatic course at the helm of the union, opposing Australian involvement in the Vietnam War and campaigning hard for the leftist economic policies of Gough Whitlam (it was argued that the ACTU became the driving force in the Labor Party under Hawke’s tenure), but coupled that with a firm support for the ANZUS alliance and Israel. In 1971, Hawke muscled through a resolution through the ACTU designed to identify and purge all elements within it that were in any way connected to Communism. The move led to demonstrations and an assassination attempt but dramatically raised Hawke’s stature, even the most conservative and anti-labor of Australians siding with Hawke in the dispute. A battle with alcoholism and the candid nature in which he portrayed his successful attempt to defeat it only increased his popularity as an honest man in the public eye. After nine years, the larger-than life South Australian felt it was time for him to try elected office, and what better place than his home state?

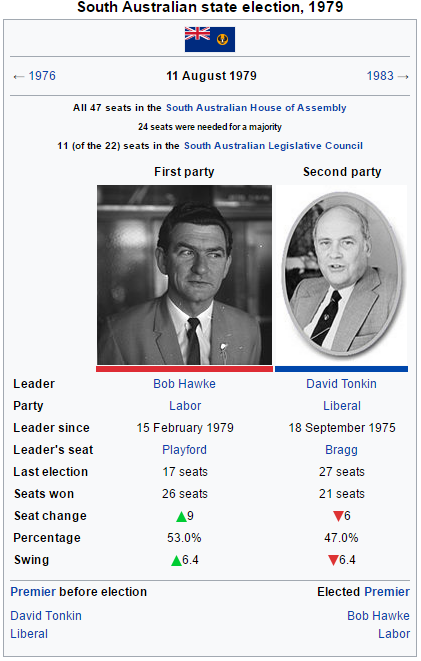

Incumbent five-year Liberal Premier David Tonkin was reasonably popular after the landslide election in 1976. Combining an agenda of fiscal conservatism and social minaprogressivism, the South Australian Liberal Party was one of the few conservative parties in the world that held a sizable minaprogressive faction. The Labor Party had been out of power since the 1968 election, coming close in 1972 but significantly weakened by the minaprogressive Social Progressive movement that took two seats and a significant chunk of the left-wing vote in 1974 and 1976. Thus, the party welcomed Bob Hawke with open arms, clearing the way for him to be easily elected leader and clearing a seat in the working-class Adelaide suburbs for him to run in. Tonkin, knowing that the charismatic Hawke would only gain in the polls when time went on, called an election soon after to capitalize on his still sizable popularity.

Liberal fears about the charismatic Hawke were well grounded. With union dissatisfaction at Tonkin considerable due to a large series of public sector cuts in 1977, Hawke was the perfect vehicle to direct them to the election effort. The ACTU and other trade unions poured resources into the election, Hawke using his considerable pull to cajole the Whitlam Government and Federal Labor to make the race a priority.

The effort and investment paid off. Hawke and Labor roared into a decisive victory, ending eleven years of Liberal control and securing Labor’s third state government (the other two were New South Wales and Northern Territory). Banking on his high-profile effort to fight communism and his culturally conservative roots, Hawke portrayed himself as the antithesis to the progressive social policies of Tonkin and made significant ironroads into traditionally Liberal rural areas. The rurals and middle-class suburbs recorded a large swing to Labor, which swept away the two Social Progressive incumbents to a nine seat gain.

The effort and investment paid off. Hawke and Labor roared into a decisive victory, ending eleven years of Liberal control and securing Labor’s third state government (the other two were New South Wales and Northern Territory). Banking on his high-profile effort to fight communism and his culturally conservative roots, Hawke portrayed himself as the antithesis to the progressive social policies of Tonkin and made significant ironroads into traditionally Liberal rural areas. The rurals and middle-class suburbs recorded a large swing to Labor, which swept away the two Social Progressive incumbents to a nine seat gain.

Very much a “reform communonationalist,” Hawke’s efforts to combat cost of living increases and provide robust public services and well-funded education secured his popularity within South Australia – enabling him and his allies to construct a powerful Labor machine which effectively controlled South Australian Labor politics. This would soon bring Hawke in direct conflict with Whitlam and the Federal Labor establishment, a fight the Premier was ready for.

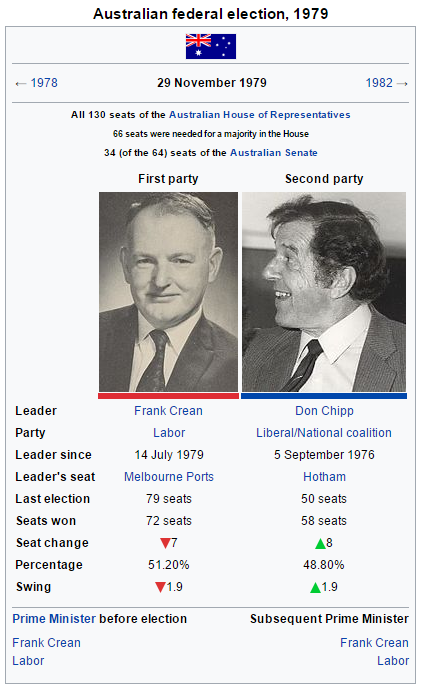

Tired after nine nonconsecutive years as Prime Minister and four as Leader of the Opposition, Gough Whitlam decided after a long talk with his family and allies to resign from his position in June 1979 – ending on a high note as the capital gains tax and tariff reform passed the Senate to become law. He left with high popularity among the Labor Party, which he had delivered to government after a long period of opposition for nearly twenty years during the Menzies era, and was seen positively by most of the public. In the resulting Labor leadership spill, the party selected Deputy Prime Minister, Minister of Industry, and MP for Melbourne Ports Frank Crean to be their new leader

Foreign policy soon moved to the forefront of Crean’s early tenure. Due to the Wallace and Reagan foreign policy guidelines, America’s foreign allies were increasingly encouraged to develop their own military and intelligence strength to combat the spread of the Soviet Empire. Australia was no exception. Though Whitlam, an ardent opponent of the Vietnam War, didn’t seek to commit any Australian troops abroad he did increase Australian military aid and keep the defence budget at a decent level. The major fight facing the nation was the Moro insurgency in the Philippines, where communist-aligned Moro tribesmen on Mindanao were fighting for independence from Manila with Chinese and Soviet backing. Whitlam had been providing aid, but Crean – having called a general election to take advantage of the government poll numbers – increased the aid and made helping fight communism the centerpiece of his election strategy.

As with their British counterpart a year later, Labor held onto power with a reduced majority. About half of the rural seats that were won on the Whitlam landslide the year before passed back into the Coalition’s grasp (Labor turned National MP Bob Katter Sr. winning his old seat back after losing it in 1978), while four seats in the inner suburbs of traditionally Liberal Melbourne fell into Chipp’s column. It wasn’t enough though, for enough rural and Mortgage Belt seats survived the modest swing against the government to provide Crean a decent margin in Parliament.

As with their British counterpart a year later, Labor held onto power with a reduced majority. About half of the rural seats that were won on the Whitlam landslide the year before passed back into the Coalition’s grasp (Labor turned National MP Bob Katter Sr. winning his old seat back after losing it in 1978), while four seats in the inner suburbs of traditionally Liberal Melbourne fell into Chipp’s column. It wasn’t enough though, for enough rural and Mortgage Belt seats survived the modest swing against the government to provide Crean a decent margin in Parliament.

However, problems began to arise rather quickly for the reelected Prime Minister. The Moro insurgency on Mindanao was growing worse, Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos pursuing a scorched earth strategy with the communists rather than attempt a hearts and minds campaign. This move led to a massive increase in violence, a series of high profile terrorist attacks in Manila, and the Australian Government forced to triple military aid while refusing to send troops to placate the Labor left (Marcos would be defeated in the 1981 Presidential election by Gerry Roxas). A small economic downturn due to rising inflation hurt the government’s poll numbers, and commitments to fund expansions of Gough Whitlam’s programs prevented Crean from truly stimulating the economy.

All of Crean’s problems were smack in the middle of his high profile squabble with Bob Hawke. The Federal Labor Party fumed at the independent machine under Hawke’s control, which had resulted in two incumbent Whitlam and Crean allies in the state defeated for preselection by ACTU stalwarts in the 1979 election. Hawke was not seen as a team player, and this was reinforced by the public comments Hawke had made to the press about the federal government’s policies. He viewed Crean’s economic efforts as “out of touch” and “unbelievably daft” in an interview with the Age, saying that the government was more concerned with badly-planned foreign adventurism – Crean’s move to both offer aid and prevent sending troops – and economic orthodoxy than combatting inflation and increasing the quality of life for average Australians. Crean’s deal with the leftist faction of the party and appeasement practice with several major unions was criticized by Hawke, who had entered into the Accord of Cooperation with the unions in South Australia for them to restrict demands for wage and benefit increases for firm commitments on certain issues from the government. When asked who was getting it right, Hawke smiled and stated “Joh,” referring to the Queensland National Premier and Hawke’s unlikely friend (who had also entered into an accord with the ACTU).

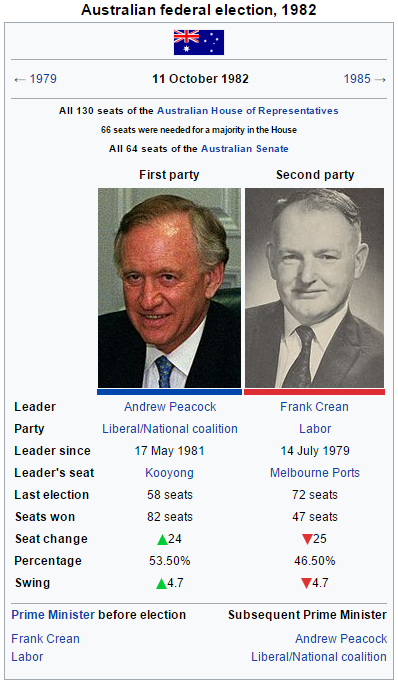

This comment exacerbated the feud between Crean and Hawke partisans, eclipsing Coalition infighting which had been the staple of the past decade. In fact, after Chipp stepped down as leader in 1981, the Coalition had pushed through a compromise leader in Victorian MP and former Foreign Minister Andrew Peacock, demonstrating a show of unity to take advantage of the Crean-Hawke feud. Unable to delay for more time, the Government was forced to call for an October 1982 federal election. They campaigned hard, but there was a sense of despondency against what was developing to be a Peacock juggernaut.

After four consecutive Labor victories (five victories out of the last six elections), The Coalition was swept back into power on a massive swing. Every single seat in Queensland toppled into its column thanks to Joh’s efforts, joining Tasmania and the single Northern Territory seat as fully held by the Coalition. The swing was large enough to pull in an unendorsed Liberal candidate as an independent in the western Adelaide seat of Hindmarsh, largely due to Bob Hawke cutting off support from the state apparatus due to his dislike of the Labor incumbent. Ten years of Labor and the increasing interest rates and the worsening situation had crippled Crean’s government, and the infighting with Hawke hurt confidence as to the disciplined Peacock campaign, which ruthlessly put down any inkling of factionalism. The margin was the largest for any government since Robert Menzies, Peacock leading the Liberal and National parties in a joyous celebration after ten years in the wilderness.

After four consecutive Labor victories (five victories out of the last six elections), The Coalition was swept back into power on a massive swing. Every single seat in Queensland toppled into its column thanks to Joh’s efforts, joining Tasmania and the single Northern Territory seat as fully held by the Coalition. The swing was large enough to pull in an unendorsed Liberal candidate as an independent in the western Adelaide seat of Hindmarsh, largely due to Bob Hawke cutting off support from the state apparatus due to his dislike of the Labor incumbent. Ten years of Labor and the increasing interest rates and the worsening situation had crippled Crean’s government, and the infighting with Hawke hurt confidence as to the disciplined Peacock campaign, which ruthlessly put down any inkling of factionalism. The margin was the largest for any government since Robert Menzies, Peacock leading the Liberal and National parties in a joyous celebration after ten years in the wilderness.

Taking residence in both the Lodge and Kirribilli House, Peacock wasted no time in directing the sizable majority to implement his agenda. A large series of individual tax cuts were passed – the largest in Australian history and modeled after the tax cuts of Ronald Reagan and New Zealand Prime Minister John Anderton – and drastic action was taken by the Departments of Treasury and Finance to slash the high interest rates. Further aid was provided to the Philippines, Foreign Minister Malcolm Fraser meeting with President Roxas to announce a small Australian military force to deploy to Mindanao to help fight the rebels. An attempt was made to nix the Australia Card legislation before it was implemented, but the move failed in the Senate and was abandoned in a huge loss for Peacock. It had been one of his key campaign promises. Still, his poll numbers were high and confidence in the economy was rising steadily.

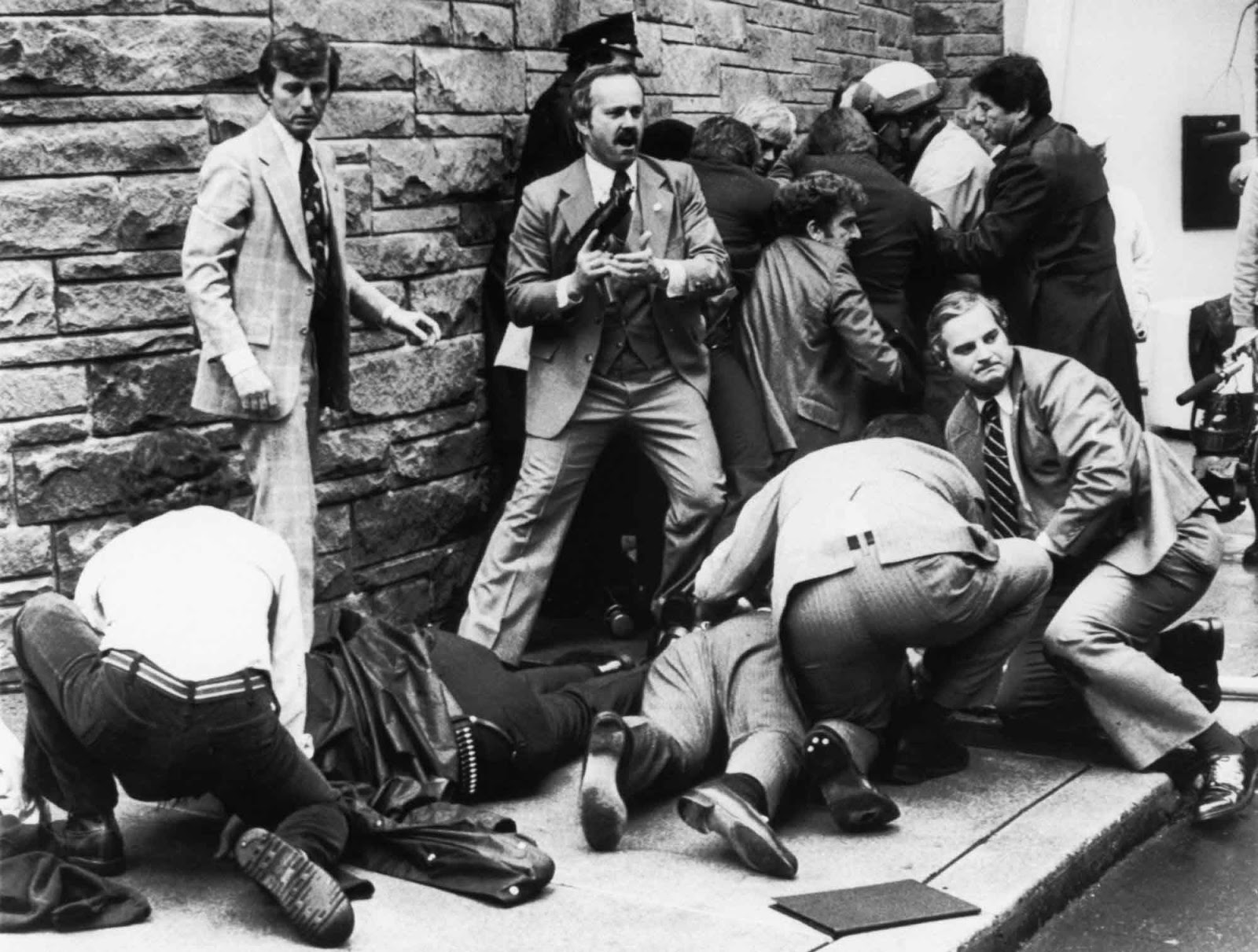

Tragedy soon struck, however. On June 2nd, 1983, while visiting his constituents in Kooyong, Peacock was heading to a meet-and-greet session with voters about the tax cuts in the official limousine from Melbourne Airport. Waiting near the secondary school – where the meeting was held – were two individuals, George Samuels and Federico Rojas (one a white Australian and the other a Filipino immigrant). Both were committed Communists, and angry about the Australian military mission to the Philippines. When the Prime Minister arrived, they removed two AK-47 assault rifles smuggled into Australia by the MNLF and opened fire on the limousine. Police would wound and capture the two when they stopped to reload, but not before they killed two of the Prime Minister’s detail and caused the vehicle to crash into the side of the school. Prime Minister Peacock was badly wounded in the altercation, put in a coma for nearly two weeks and hospitalized for over four months.

The terrorist attack shocked and horrified Australians, who had been largely isolated from major conflict for nearly their entire history. Calls to bring back the death penalty (it had been abolished by the Second Whitlam Ministry in 1973) reached a fever pitch, as did further action against the Moro insurgents. Peacock, looking at months of difficult rehabilitation, made a choice. On June 18th he tendered his resignation, citing his inability to serve the office properly in his condition – he’d return to the Cabinet after his discharge, only in a less strenuous position.

Peacock’s resignation left the Coalition in an untenable position. Peacock had been a compromise choice in the feud between the Gorton/National wing and the Chipp wing of the party, a member of the latter while running on the platform of the former. Most thought Finance Minister Philip Lynch was the perfect option, but Lynch died of a stroke only a month after the Kooyong Attack. Jockeying continued again, the nominal frontrunner Foreign Minister Malcolm Fraser opposed by the populist conservatives led by Joh Bjelke-Petersen, who was sick of small L liberal leaders from Victoria and demanded National leader Ian Sinclair be made PM. Finally, Industry and Commerce Minister John Hewson proposed a compromise, one both pleased the moderates and Joh. Treasurer and Member of Parliament from Bennelong John Howard, a liberty conservative from New South Wales.

Howard was a bit of a boy wonder in the Liberal Party, elected in 1972 to the north Sydney seat of Bennelong with a modest swing to him while the Snedden Government was getting creamed in NSW. He rapidly rose to Shadow Treasurer when Don Chipp took over from John Gorton as leader, gaining a reputation as a solid liberty conservative in the Reagan school, as well as a foreign hawk and social conservative. He had close ties to the parliamentary National Party, who extolled his attributes to party boss Joh. Howard drew wide support for his work on the tax cuts and battling inflation, and despite his lack of charisma he was quickly selected as Prime Minister and Leader of the Liberal Party by the caucus.

Howard was a bit of a boy wonder in the Liberal Party, elected in 1972 to the north Sydney seat of Bennelong with a modest swing to him while the Snedden Government was getting creamed in NSW. He rapidly rose to Shadow Treasurer when Don Chipp took over from John Gorton as leader, gaining a reputation as a solid liberty conservative in the Reagan school, as well as a foreign hawk and social conservative. He had close ties to the parliamentary National Party, who extolled his attributes to party boss Joh. Howard drew wide support for his work on the tax cuts and battling inflation, and despite his lack of charisma he was quickly selected as Prime Minister and Leader of the Liberal Party by the caucus.

All Australians now looked to John Howard, all of forty-four and tied with Robert Menzies to be the third youngest Prime Minister in Australia’s history, to lead them through the new phase of the Island’s destiny.

· White: 80.0%

· Black: 10.7%

· Spanish-American: 4.2%

· Asian/South Asian: 4.0%

· Other: 1.1%

Ronald Wilson Reagan was a man with a mandate. Reelected in the largest landslide since FDR in 1936, equipped with massive congressional majorities and a strong approval rating, the President possessed immense political capital for his second term and was determined to use it before he inevitably lost it. In a pre-swearing in meeting of the senior cabinet, Reagan and Vice President Ford reiterated their desire to “go big” in terms of legislation. They would seek consensus across the aisle, but informed Speaker Brock and Majority Leader Murphy that they were expecting to play hardball if need be. Congressional leadership understood, and planned accordingly.

First on the list were the staff shakeups. Much of the foreign policy team was retained, SecDef Teller, SecState McCarthy, and NSA Webb kept on to limit changes to the Reagan Doctrine’s full steam ahead. Reagan was very close to Attorney General Brooke, so he was retained along with Chief of Staff Cheney, and Charles Percy was a new addition to SecTreas and doing a good job. However, the departure of Charles Rangel to run for Mayor of New York opened up HUD. Sensing that Caspar Weinburger was itching for a change of scenery, Reagan transferred him to HUD and asked Undersecretary of Treasury and close friend George Schultz to take HEW, which he accepted. Reagan appointed William Westmoreland to VA, starting a tradition of putting retired Generals into the position, while reorganizing the White House Staff to accommodate the confidants of Vice President Ford.

First on the list were the staff shakeups. Much of the foreign policy team was retained, SecDef Teller, SecState McCarthy, and NSA Webb kept on to limit changes to the Reagan Doctrine’s full steam ahead. Reagan was very close to Attorney General Brooke, so he was retained along with Chief of Staff Cheney, and Charles Percy was a new addition to SecTreas and doing a good job. However, the departure of Charles Rangel to run for Mayor of New York opened up HUD. Sensing that Caspar Weinburger was itching for a change of scenery, Reagan transferred him to HUD and asked Undersecretary of Treasury and close friend George Schultz to take HEW, which he accepted. Reagan appointed William Westmoreland to VA, starting a tradition of putting retired Generals into the position, while reorganizing the White House Staff to accommodate the confidants of Vice President Ford.

To avoid major fights and public relations defeats (even with the GOP supermajorities), Reagan, Ford, and the rest of his team decided to pursue the bipartisan and consensus legislation first. Talks between Senator Barry Goldwater (R-AZ), Senator Larry MacDonald (D-GA), and Representative George W. Bush (R, TX-18) had resulted in a proposal to reorganize the United States Military and Defense Department according to recommendations made by the Webb Commission after problems and military SNAFUs during the Nicaraguan Civil War – the legislation would have created a Joint General Staff Council headed by one Five Star officer and comprised of him and the other service heads, designated to develop military strategy and advise the President and SecDef on war policy. Actual command would trickle down from the National Command Authority to the actual Army and Fleet commanders in the field. The bill was endorsed by Secretary Teller and the Service Chiefs, and the house and senate leadership of both parties were committed to its passing. It passed the House 349-21 and the Senate 95-2, Reagan signing it into law in March 1981.

Efforts were also made on a broad reform of tax rates. Meeting with leaders of both parties (including inviting Progressives like Senator Leahy and Congressman John Anderson), Reagan sought a consensus compromise on the issue that could please a wide majority of congress rather than forcing through a bill on Republican votes alone – though all knew he and the leadership were willing to do it. With that threat hanging over everyone, progress on the reform was promising and officials were confident it would be ready by June.

With these bipartisan victories on his belt, Reagan hoped to use the momentum to push for the legislative holy grail, amending the constitution with several priorities of his. He had the will, had the popular support – most likely – and was confident in having the votes. However, national attention and political focus would soon shift to the Supreme Court, halting any further legislative action for the time being.

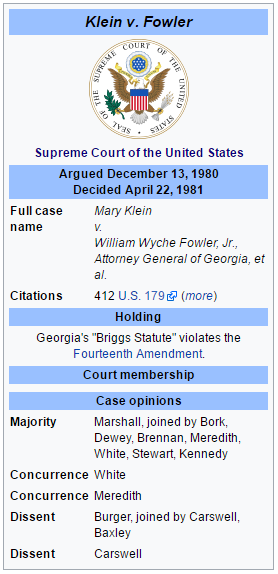

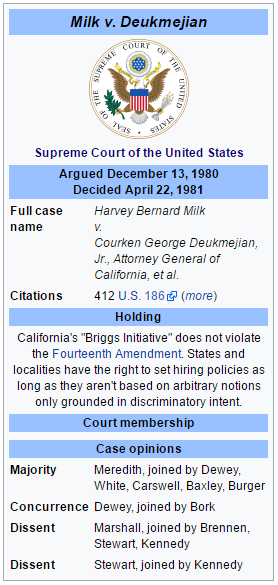

California’s Briggs initiative had a long and complicated judicial history following its passage in 1978. Banning the hiring of homosexuals in public schools, numerous challenges were filed in both state and federal courts to both restrict it and outright eliminate it. The first major challenges to reach their conclusions were two decisions by the California Supreme Court. In one decision Chief Justice Roger Traynor limited the Briggs Initiative (a constitutional amendment) to “Positions that are involved in teaching or that involve educational contact with students.” Administrative or non-educational jobs weren’t affected by the Initiative. Second, another ruling by Justice Dan Lungren extended the Initiative’s reach to both sexes.

The federal suits were far more watched by the general public, sought to strike the Initiative down on 14th Amendment grounds. Additionally, while most proponents in other states were waiting for the court cases to conclude, the state of Georgia had passed an even more wide ranging ban regarding several different government positions. As a result, two major lawsuits proceeded to the Circuit courts: Klein v. Fowler in the 4th and Milk v. Deukmejian in the 9th. The result was a split decision, the 9th Circuit striking down California’s law while the 4th Circuit affirmed Georgia’s. Granting certorai, the Supreme Court decided to argue both cases.

First announced was the decision in Klein v. Fowler. In a majority opinion written by Justice Marshall and joined by Justices Meredith, Dewey, Brennen, White, Stewart, Kennedy, and Chief Justice Bork, the Court struck down Georgia’s ban as a due process violation under the 14th Amendment. Applying the same justification as the decision in Brown v. Board of Education, Marshall wrote on how the ban was far too broad in scope and acted as governmental violation of the rights of homosexual citizens. Justice White filed a concurrence, as did Justice Meredith (who referenced his experience under Jim Crow to attack Georgia’s broad ban as the same government discrimination that the Constitution prohibited). Justice Burger, joined by Carswell and Baxley, dissented on the same grounds as he did in Henry v. Minnesota.

First announced was the decision in Klein v. Fowler. In a majority opinion written by Justice Marshall and joined by Justices Meredith, Dewey, Brennen, White, Stewart, Kennedy, and Chief Justice Bork, the Court struck down Georgia’s ban as a due process violation under the 14th Amendment. Applying the same justification as the decision in Brown v. Board of Education, Marshall wrote on how the ban was far too broad in scope and acted as governmental violation of the rights of homosexual citizens. Justice White filed a concurrence, as did Justice Meredith (who referenced his experience under Jim Crow to attack Georgia’s broad ban as the same government discrimination that the Constitution prohibited). Justice Burger, joined by Carswell and Baxley, dissented on the same grounds as he did in Henry v. Minnesota.

The victory for gay rights groups was coupled with a stinging defeat. Announced right after was the decision in Milk v. Deukmejian. After his concurrence in Klein, Justice Meredith took the opposite approach in Milk, writing for the majority including Dewey, White, Carswell, Baxley, and Burger. The California Briggs Initiative, unlike that in Georgia, was not discriminatory under the 14th Amendment due to its narrowed scope. Meredith stated that the focus on “one specific profession in the Government platter of offered employment” did not show a broad pattern of discrimination. “A gay or lesbian individual could still find employment in any other government employment, and the law of California would protect him from being asked about his or her sexual predilections.” The restrictions imposed by the law counted as something concerning fitness for the job, and although he disagreed with legislation he believed the state had the power to decide the opposite for reasoning not grounded in arbitrary notions. “One cannot call it discrimination to prevent a person bound in a wheelchair from taking a job as a construction worker. I disagree with the conclusion that a homosexual individual is not fit for teaching impressionable minds, but this is a decision best left to the democratic process.” Justice Dewey, joined by Chief Justice Bork, wrote a concurrence stating that the California’s Supreme Court limitation of the Initiative convinced him to vote to uphold. Had the law applied to all jobs in schools rather than just to teachers, he might have gone the other way. Justice Marshall and Stewart’s dissents went with the same reasoning in the majority in Klein.

The backlash was swift. Social conservatives saw this as a massive win despite the Georgia statute’s defeat (most of them weren’t thrilled at the scope of that law). Televangelist Pat Robertson, the son of a Democratic Senator himself, praised the decision in announcing his run for Senate as a Democrat against freshman John Warner (R-VA). Sam Yorty and Barry Goldwater Jr. claimed “Democracy won” and George Wallace stated “The will of the Court must be respected.” However, liberal groups were even more vociferous in their opposition. Jerry Brown was “greatly disappointed,” while Ramsay Clark called it a “Black stain upon the republic.” Protests took to the streets, with many justices burned in effigy. Justice Dewey got much of the heat – previously a gay rights icon for the decision striking down sodomy laws in Henry, he was called a turncoat, Benedict Arnold, or Hanoi Jane by many, activist Gloria Steinem labeling him “Worse than Hitler.”

His health not being the best for the past few years – and considered the most likely retirement prospect of all the members of the court since John Marshall Harlan died nearly a decade before – Dewey took a three week sabbatical to his resort home in Palm Beach, Florida to recuperate with his second wife. Justices Brennen, Stewart, and Burger, whom he was closest to on the Court, all wished him well and recommended he retire. Dewey demurred, promising to think it over while resting in the Florida sun. His wife would later say he planned to wait until the current case load was completed before finally retiring after a life in the spotlight.

Reagan was faced with his third vacancy to fill, and unlike the other two he was boxed in by a campaign promise – to appoint the first woman to the Supreme Court. There weren’t many candidates, unfortunately due to the cadre of woman lawyers being appointed to high courts being rather sparse until recently. The President’s advisors were split on who to choose. Gerald Ford suggested Deputy Secretary of Transportation Elizabeth Dole, White House Counsel Edwin Meese pushed for District Judge Carol Mansmann, and Attorney General Brooke thought Arizona Attorney General Sandra Day O’Connor was the best choice. Reagan assessed his options at Camp David.

In the end, Chief of Staff Dick Cheney came up with who Reagan would eventually choose, given to him from his friend Illinois Governor Donald Rumsfeld. Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals Judge Phyllis Schlafly.

Upon the announcement in the White House, the nomination caused quite a stir. Schlafly wasn’t the normal judicial nominee, someone with legal and judicial experience that most people hadn’t heard of. For the past two decades she had been at the forefront of the latest social and political battles of the day as a commentator, activist, and organizer. She had risen to national prominence fighting the Equal Rights Amendment, but when it failed to pass the House of Representatives in 1973 she shifted her gears to focus on fighting “Judicial Activism” in the courts. As a pro bono lawyer she had ended up arguing several major cases in front of the Supreme Court, and as a result of her prominence and conservative views Reagan had appointed her to the 7th Circuit. Her previous fire had cooled massively, and despite expectations she took to her new judicial career with calm and methodical reserve, a record not similar to jurists such as Peirce Butler or Willis Van Devanter but without the controversy of her earlier activism.

Upon the announcement in the White House, the nomination caused quite a stir. Schlafly wasn’t the normal judicial nominee, someone with legal and judicial experience that most people hadn’t heard of. For the past two decades she had been at the forefront of the latest social and political battles of the day as a commentator, activist, and organizer. She had risen to national prominence fighting the Equal Rights Amendment, but when it failed to pass the House of Representatives in 1973 she shifted her gears to focus on fighting “Judicial Activism” in the courts. As a pro bono lawyer she had ended up arguing several major cases in front of the Supreme Court, and as a result of her prominence and conservative views Reagan had appointed her to the 7th Circuit. Her previous fire had cooled massively, and despite expectations she took to her new judicial career with calm and methodical reserve, a record not similar to jurists such as Peirce Butler or Willis Van Devanter but without the controversy of her earlier activism.

Aside from the nomination of John Rarick – which was opposed strenuously due to the special circumstances of his divisiveness and the Wallace Court expansion scheme, Bill Baxley seen as more consensus choice – judicial nominees had a longstanding tradition of presidential deference attached to them. They weren’t politicized, and the Senate largely only inquired into the temperament and qualifications of the nominees. Opposition to Schlafly from many interest groups and advocates, however, was fierce. Feminist organization, still seething over the defeat of the ERA, attacked her nomination intensely. They were joined by the ACLU and other liberal groups, who put immense pressure on them. The Eastern Establishment, noting her advocacy against President Rockefeller during the 1964 primaries, also opposed her and managed to convince many moderate Republicans (and Independent Joe Biden) to oppose her nomination.

However, the sheer size or the Republican majority and the support of Strom Thurmond and the right-wing of the Democratic caucus in the senate killed the opposition before it could form. Schlafly’s hearings were contentious, the nominee calmly debating judicial theory with the Senators in a move breaking with that of previous nominees (though James Meredith had been famously acerbic toward his critics). Senator Medgar Evers, who had been given a plum spot on the Judiciary Committee, defended her nomination, convincing a skeptical NAACP to endorse Schlafly’s confirmation. Even with the opposition, she managed to pass the senate 63-33 and make history as the first woman on the Supreme Court of the United States.

Conservatives and southerners hailing Schlafly’s appointment as the final cementing of the first judicially restrained SCOTUS since Willis van Devanter had retired and broke up the Four Horsemen opposing FDR’s policies. Bill Baxley always had been moderate on economic regulatory issues, but the replacement of Dewey gave a solid six vote majority: Bork, Stewart, Burger, Carswell, Meredith, and now Schlafly. However, the Democratic support of Schlafly (mostly by Minority Leader Thurmond, Helms, Stennis, Maddox, and Exon) had been the final straw for many on the left of both parties. It was increasingly obvious that the minaprogressives and social liberals had no home in either major party. It was not a question of if it would boil over any more, but now when it would boil over.

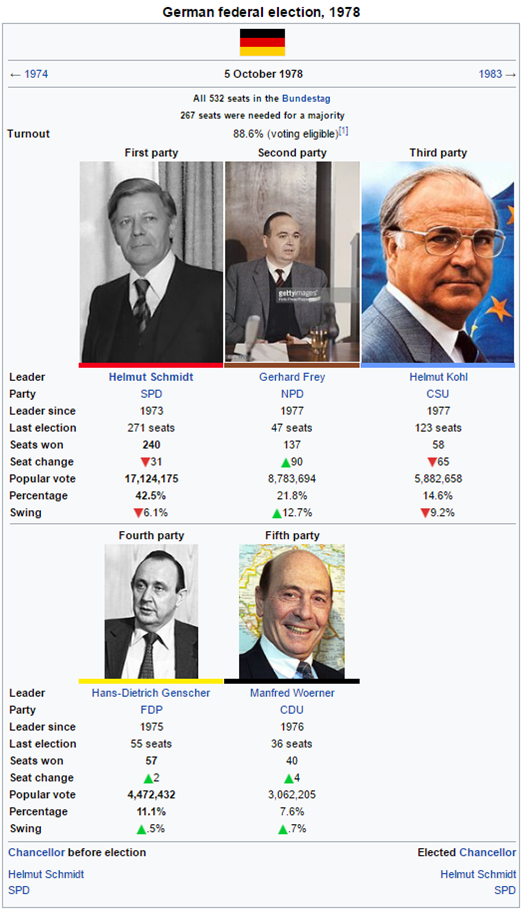

One of the stranger and more unique ideologies to emerge in the chaos of the seventies was Freyism, named after its ideological father Gerhard Frey – a notorious German nationalist and far-right writer. Combined with others such as Hans-Ulrich Rudel and Austrian émigré Kurt Waldheim, the initial ideology of the promotion of human freedom had morphed into the “Prussian School,” an application of the various proscriptions in Frey’s bestseller Das Freiheitreich to a coherent governing strategy. The Prussian School’s doctrines followed the book’s guidelines faithfully, advocating the creation of a nation-state dedicated to the securing of human rights and exportation of human freedom across the globe. To the German people this was an attractive move, given their… sketchy history on the subject to say the least. What Frey, Rudel, and Waldheim (along with many foreign Prussian School adherents) felt was that such a state was inherently vulnerable to falling. To overcome this, a single person or institution needed to be given immense prestige and soft power while remaining nothing more than a figurehead in regards to actual political power. Was this to be a monarch, a religion, or something else the philosophers didn’t say, but Frey was committed to applying his theory to the political sphere. And late 1970s Germany had just the vehicle for him to do so.

The NDP following the 1974 election was a party at the verge of a crossroads. The collapse of Kurt-Georg Keisinger’s government and the CDU bled nationalist voters to the ultranationalist party, many finding it the best of bad options. Now that they were expected to govern the inherent problems with the leadership began to move to the forefront. Founded by far-right nationalists, the party initially was nothing more than neo-Nazis and German expansionist diehards that were toxic in the post-WWII Germany. The large collection of new members acquired from the CDU hoped to remove the current leadership and displace the old guard of the party, and in their desperation Gerhard Frey emerged. In Germany, where nationalism was frowned upon at best, the nature of Freyism and its focus on human freedom were seen by the new voters as a perfect middle ground between merging the NDP with one of the older parties and keeping the toxic old guard in charge. At the annual party conference in 1977, the party faithful booted out the old leadership and brought Frey and his disciples in. Just as the election season was heating up.

Chancellor Helmut Schmidt was at the height of his popularity. The economy had improved, and the German counterterrorism and police forces had largely stamped out the Rotkampferbund militancy. Many West German voters saw him as a moderate and practical manager and doer, who focused on getting concrete political and economic results more than on political rhetoric – a leading indicator that put him above more charismatic party leaders that sought to inspire the populace. This hurt new CSU and CDU leaders Helmut Kohl and Manfred Woerner in the opinion polls, both struggling to hurt Schmidt’s advantage on competency. This was joined by the spike in the NDP’s numbers after Frey took control. Attacks on him, deputy leader Waldheim, and shadow defense minister Rudel for alleged “Neo-nazism” (true for Rudel, but long repudiated) was largely rejected by the German people due to the well-known nature of Frey’s views and rhetoric, and the desperation of many to atone for the past while still keeping Germany strong. Slowly but surely the party began to gain more and more right-leaning voters.

The chaos and realignment that the collapse of the CDU injected into the German political system began to recede in 1978 to a new paradigm. Helmut Schmidt and the SPD government was retained but losing its absolute majority – which was considered a given anyway due to the extraordinary circumstances as to it being obtained four years before. The government had planned accordingly, and were able to strike a coalition agreement with the increasingly pro-business minaprogressive FDP to maintain governance. On the right-wing, the CSU was displaced as the main opposition party by Gerhard Frey’s NPD. The abandonment of the traditional nationalistic elements for Freyism had resonated far and wide among the German right, spiking the party’s vote share by nearly 13 points and placing it 100 seats behind the dominant SPD.

The chaos and realignment that the collapse of the CDU injected into the German political system began to recede in 1978 to a new paradigm. Helmut Schmidt and the SPD government was retained but losing its absolute majority – which was considered a given anyway due to the extraordinary circumstances as to it being obtained four years before. The government had planned accordingly, and were able to strike a coalition agreement with the increasingly pro-business minaprogressive FDP to maintain governance. On the right-wing, the CSU was displaced as the main opposition party by Gerhard Frey’s NPD. The abandonment of the traditional nationalistic elements for Freyism had resonated far and wide among the German right, spiking the party’s vote share by nearly 13 points and placing it 100 seats behind the dominant SPD.

Not willing to rest on his laurels, Frey began negotiations with Kohl and Woerner to consolidate the right-wing into a single party, grounded in Freyist principles. The task was considered difficult by most insiders, but Frey was confident he could pull it off. For the sake of his cause he hoped to pull it off.

The NDP wasn’t the sole major party that espoused the principles of Freyism as their main ideology. Two parties that possessed political control of their respective nations had significant Freyist tendencies, the Spanish National Democratic Party and Japan’s Minseito. A large portion of the Spanish Falangists were explicitly Freyist, while Prime Minister Yukio Mishima sought to create Freyist guidelines to conform the Japanese military to the post-WWII Japanese Constitution. The other main parties that established the ideology were smaller ones, popping up across Europe and former authoritarian nations (including the growing Solidarity movement in Poland, led by Trade Union President Lech Walesa).

One of the most intriguing was the Party of the Free Democratic Left, the junior coalition partner of the Italian coalition government, led by the current Minister for Industry Enrico Berlinguer. A former Communist and contender for the leadership of that party – instead losing to the Soviet-aligned Giangiacomo Feltrinelli – Berlinguer left in disgust with its explicitly pro-Moscow and pro-Focoist stance. Knowing that the initial desire for liberation from oppressive interests was what began the Communist movement, Berlinguer felt that the current movement was mired in authoritarian and tyrannical elements. As such, he and several members of the party abandoned it to form the Free Democratic Left, combining Freyist ideology with “Eurocommunism.” It would be a key part in forming the coalition government of Italy to keep the Communists out, managing to secure several major priorities, including the democratization of the trade unions and expansive rights for women in Italian society.

Though a rightist in his ideology, Frey held no qualms of allying with whatever persons that he could find common ground with in the movement, be they far-right nationalists or disillusioned communists. He and Berlinguer would end up close friends, the former serving as the latter’s best man at Burlinguer’s second wedding in 1981. Leftist and rightist Freyism, despite the other ideological differences, were joined at the hip – after the first International Congress of Human Freedom held in West Berlin in 1979, Frey and the other party leaders charted a path to ensure that continued to be the case.

Though a rightist in his ideology, Frey held no qualms of allying with whatever persons that he could find common ground with in the movement, be they far-right nationalists or disillusioned communists. He and Berlinguer would end up close friends, the former serving as the latter’s best man at Burlinguer’s second wedding in 1981. Leftist and rightist Freyism, despite the other ideological differences, were joined at the hip – after the first International Congress of Human Freedom held in West Berlin in 1979, Frey and the other party leaders charted a path to ensure that continued to be the case.

Outside mainland Europe and formerly authoritarian nations that now permitted some degree of free expression, Freyism was slow to develop. Tony Benn and Paul Hellyer seemed to dabble in the ideology, but given their personalities it was seen more as an eccentricity rather than a change in their outlook. For the most part, the Anglosphere largely rejected the Prussian School of the movement – nowhere was this more prominent in the United States. The doctrines of communonationalism, liberty conservatism, and minaprogressivism were established for the most part in each side of the debate, and the nature of individual liberty and the Bill of Rights (as well as the success of the African-American Civil Rights Movement) prevented the widespread historical totalitarianism and repression that made Freyism so attractive in places like Germany and Japan. Additionally, and perhaps most importantly, the basic structure of the Prussian School was rejected. Americans’ distrust of royalty, state religion, and largely undemocratic bodies serving as a symbol of national greatness really hurt the spread of the ideology. Many wondered if it would ever be established in the United States.

Those predictions were put to rest by the actions of one man – a shocking, yet at the same time predictable choice. John G. Schmitz.

Universally hated in the seventies an associate of Dixiecrats, segregationists, and George Lincoln Rockwell, following his gubernatorial campaign Schmitz had left such associations and famously repudiated them every chance he got. He endured several assassination attempts from disgruntled white supremacists, once having to draw his permitted Colt .45 and mow one down in 1977, making national headlines. The biggest benefit to his career was Evan Mecham’s selection of him to be his running mate in the 1976 election, a decision Mecham would rue for the rest of his life. Not that he was a liability, but because Schmitz outshone Mecham in the spotlight.

It was in 1976 that Schmitz publically aired his Freyist views, but it had been building since he had read Das Freiheitreich for the first time, finding an outlet for the extensive self-loathing of what he had done in his past. American to the core however, Schmitz sided with the rest of his countrymen in dislike for the Prussian School ideas. The application of state religion or a monarch – powerless as they may be – was an anathema and a nonstarter. Freyism was the solution, but the means had to be changed for the American people to swallow it.

In 1977, Schmitz capitalized on his newfound nationwide notoriety and published a semi-biographical book on his philosophical journey and ideas. His critics, of which there were many, condemned the idea as “Dred Scott volume two” after an infamous comment when Schmitz said he couldn't find any legal problems with the case. He cleverly decided to one up the critics and embraced the role, naming his book Not-Dred Scott and marketing it as the complete refutation of bigotry. He detailed, in complete chronological order, how he had become a Nazi and how he repudiated the ideology. William F. Buckley would refer to it as “To American Racism what Whittiker Chambers was to American Communism.” Several criminal conspiracy convictions would later result from Schmitz’s accounts, he himself testifying for the prosecution in all of their trials.

What would contribute to the very ideological fabric of America was the second and third sections of the book, which detailed Schmitz’s Freyist theory – hereafter known to the world as the Virginia School of Freyism (after a speaking engagement at the University of Virginia where he first outlined it). The base doctrines that were illustrated in Das Freiheitreich were kept, too universal to be done away with. However, Schmitz expressly criticized the Prussian School’s hope for a single figurehead person or organization to rally the populace around and to deploy soft power to maintain human freedom. Instead, he argued, “The very nature of human freedom itself is what the populace will rally for. A government formed in the defense of liberty and emancipation will provide the perfect banner to join side by side in its defense. A nation fully committed to these beliefs and universal teachings, as ordained by God, will persevere and form an unstoppable juggernaut free from localized despots and religious organizations inclined to sow division between the different cultures of the world rather than the needed unity.” Schmitz would later go on to argue that the United States of America – minus a few issues that could be fixed – served as the archetype of a free nation that could liberate the world in the Befreiungskrieg. Some in the Prussian School criticized the book, but overall the Freyist community praised Schmitz for his well-written points.

Not-Dred Scott would be an international bestseller, topping the New York Times bestseller list for seven weeks running and made Schmitz a multimillionaire. It would be translated into over fifty languages, and Gerhard Frey himself would invite the Californian to Bonn to discuss ideology – along with a shared laugh over the title. Back in Schmitz’s home in San Diego, manager and rising radio star Rush Limbaugh finally completed negotiations to create a syndicated talk radio program with Schmitz as the host. New Day with Congressman John G. Schmitz would premier on July 2, 1978, Martin Luther King Jr. providing the first ever guest interview following the opening theme, the Battle Hymn of the Republic.

Schmitz laughing at protestors outside one of his many speaking engagements.

Initially confined to Southern California, Schmitz’s home turf, the increase in radio syndication brought numerous wealthy investors and media moguls to capitalize on the controversial host’s charisma and fire. He had a national profile, and controversy always sold. In 1981, Schmitz would be given a contract to extend his audience to the San Francisco Bay Area. This would eventually reach the whole country by 1985, and extend to Canada in 1988. In the 1990s New Day would be the most listened to radio program in the entire nation, Schmitz becoming one of the most influential people in the United States. His success would bolster the talk radio industry, which largely started expanding with the signing on of Hunter S. Thompson (Schmitz’s most loyal rival, though the two would largely get along) for his own talk program based in Denver.

Freyism had a start in the United States, and though it remained small, the mainstreaming moves by Schmitz began to win several major converts. Some would soon make their mark on history such as Bobby Fisher, Andrew Breitbart, and Mariska Hargitay.

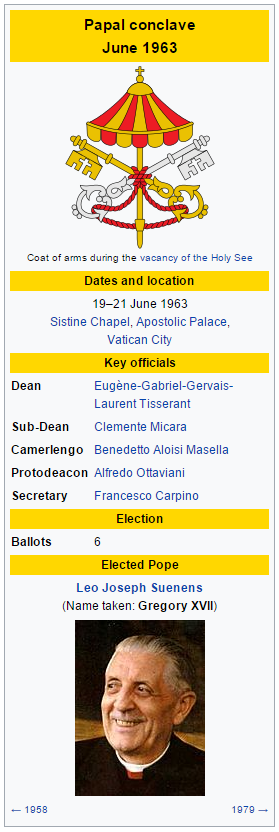

With the backdrop of the Second Council, the College of Cardinals gathered at the Sistine Chapel to elect the new Bishop of Rome. The initial favorite and alluded as the deceased John’s successor was Giovanni Battista Montini, the Archbishop of Milan. A moderate conservative that would stick by the reforms of the council, it was hoped he would gain considerable support from both the pro-reform and anti-reform portions of the College as a compromise. However, he unexpectedly declined for reasons he never fully stated. Two more days of balloting and a scramble for votes from both blocs ended in the pro-reform Archbishop of Mechelen-Brussel Leo Joseph Suenens. Belgian-born, he would be the first non-Italian pope in centuries.

Ascending to the papacy, Sunenes took the name of the last French-speaking pope, styling himself Gregory XVII. Pledging to implement the reforms of the Second Council, hopes were high that the new pope would lead the Catholic Church into the new era. No one, however, would truly predict what happened next during the course of Gregory’s Papacy. And – somewhat ironically – the main driver would be a child of the reformation, not of St. Peter.

Ascending to the papacy, Sunenes took the name of the last French-speaking pope, styling himself Gregory XVII. Pledging to implement the reforms of the Second Council, hopes were high that the new pope would lead the Catholic Church into the new era. No one, however, would truly predict what happened next during the course of Gregory’s Papacy. And – somewhat ironically – the main driver would be a child of the reformation, not of St. Peter.

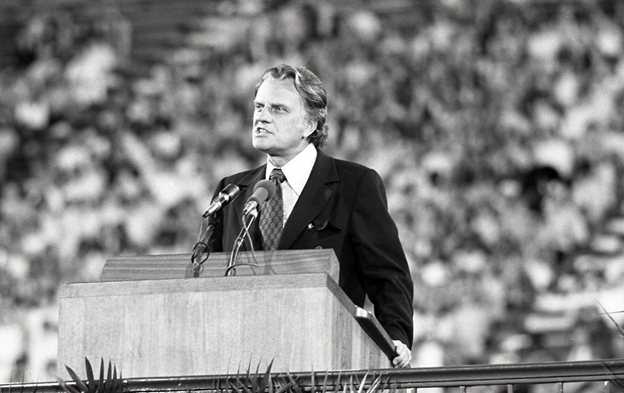

If there was anyone that represented the face of American Christianity, it was William Franklin “Billy” Graham Jr. A Southern Baptist minister since 1947, the North Carolinian had made his mark through mass revival meetings across the nation – dubbed by him as “Crusades” in direct reference to the Medieval Era campaigns to preserve the Holy Land for Christendom. Eventually televised by major networks and branching out to be held around the world, they followed a set pattern. Graham would rent a large venue, such as a stadium, park, or street. As the sessions became larger, he arranged a group of up to 5,000 people to sing in a choir. He would preach the gospel and invite people to come forward and were given the chance to speak one-on-one with a counselor, to clarify questions and pray together.

Focusing on growing the evangelical movement within the United States – including a major role in the Civil Rights demonstrations due to his close friendship with Martin Luther King, whom he would invite to deliver a sermon alongside him at the Atlanta Crusade of 1967 – world developments drew Graham’s interest to a greater cause. Upon the Soviet-backed assassination of Josip Tito and the radical communist takeover of Yugoslavia, the new government began increased pogroms and purges directed at the established clergy. Churches across the nation had been strong supporters of Tito in the final years of his reign, when the pressure from Semichastny to take a hardline communist stance was at its highest. Refugees streamed out of the nation in boats, often telling stories of recalcitrant priests getting carted away to parts unknown, or shot by communist security forces.

As anti-communist as any American, the experiences of managing several refugee assistance centers in Italy greatly affected Graham. Opinions about the dangers of focoist communism hardened, and as the Soviet Empire began to expand into the Christian nations of Africa and South America he felt something had to be done.

Teaming up with a series of evangelistic and similar-minded clergymen and activists across the world (including but not limited to Ian Paisley, Trevor Huddleston, Jerry Falwell Sr., Martin Luther King Jr. – willing to come out of semi-retirement to take part in a new venture – Fred Nile, and Reinhard Bonnke), Graham transformed the Billy Graham Evangelical Association into one with a far larger worldwide reach. Speaking at a mega-Crusade in London on Easter Sunday 1971, the first of the new venture which would be called by future social and religious scholars as the “Third Great Awakening,” the Reverend and his fellow “Crusaders” pointed to a new mission statement. While still focusing on the same issues as characterized the past Crusades, Festivals of Light (which were the applicable evangelistic movements in the British Commonwealth), and the Versammlung zum Erwachen (Assembly for Awakening, a neo-Freyist Christian movement in West Germany led by young pastor Reinhard Bonnke), the goal was to combat the worldwide spread of communism through the introduction of “Faith to fill the wanting soul of our human brethren enslaved under godless communism.” Something that the people under communism – especially after the Focoist Coups – were seen by Graham as desiring greatly and that more traditional churches were ill equipped to provide them.

Teaming up with a series of evangelistic and similar-minded clergymen and activists across the world (including but not limited to Ian Paisley, Trevor Huddleston, Jerry Falwell Sr., Martin Luther King Jr. – willing to come out of semi-retirement to take part in a new venture – Fred Nile, and Reinhard Bonnke), Graham transformed the Billy Graham Evangelical Association into one with a far larger worldwide reach. Speaking at a mega-Crusade in London on Easter Sunday 1971, the first of the new venture which would be called by future social and religious scholars as the “Third Great Awakening,” the Reverend and his fellow “Crusaders” pointed to a new mission statement. While still focusing on the same issues as characterized the past Crusades, Festivals of Light (which were the applicable evangelistic movements in the British Commonwealth), and the Versammlung zum Erwachen (Assembly for Awakening, a neo-Freyist Christian movement in West Germany led by young pastor Reinhard Bonnke), the goal was to combat the worldwide spread of communism through the introduction of “Faith to fill the wanting soul of our human brethren enslaved under godless communism.” Something that the people under communism – especially after the Focoist Coups – were seen by Graham as desiring greatly and that more traditional churches were ill equipped to provide them.

The actions by the Crusaders would take nearly a decade to truly take effect, the newly rejuvenated Evangelical movement – disheartened by the counterculture, wars, and advance of communism in the early and mid-seventies – would breathe needed air into worldwide Christianity. A breath that it desperately needed in the post-modern world.

The newfound evangelism and revival that characterized the Third Great Awakening wasn’t simply limited to Protestantism. Due to the rapid spread of communist governments thanks to revolutionary Focoism, a large percentage of Catholics the world over found themselves subjugated to regimes that were completely hostile to religion in any form (while some governments were more tolerant such as, surprisingly, Che Guevara in West Cuba due to an uncanny ability to placate the masses, others such as the Argentinians or the Polish military Junta conducted mass suppression of the Catholic Church in revolutionary zeal). A large contingent of the College of Cardinals, mainly from the United States, Eastern Europe, or South America, were increasingly mimicking the rhetoric of Billy Graham and the other Crusaders, called by the press the “Defenders of Rome” in an editorial by the New York Times. They favored a more hardline approach against communism through the use of an evangelistic approach to the faith, and grew in strength as the years passed following the Focoist coups.

Much of what the Papacy dealt with as the seventies progressed involved frantic lobbying and rendering assistance for the faithful, taking a great toll on Pope Gregory – especially after Brazil fell, the Goulart Government unable to stem the radical moves the Communists in the cabinet were ramming through the legislature. Suffering from chronic stress and several infections, he decided in 1978 to voluntarily retire back to Belgium, the first pope in centuries to voluntarily resigning on his own accord.

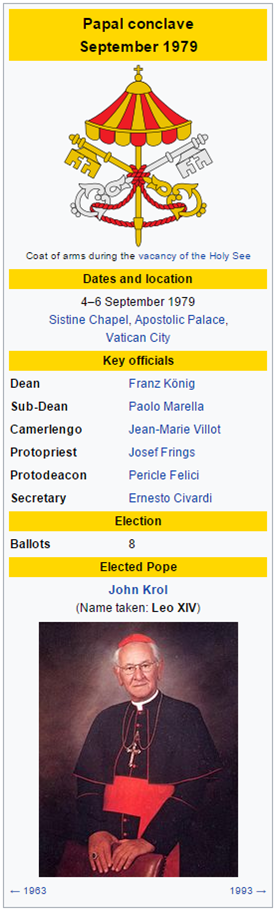

On September 4th, the College of Cardinals gathered at the Sistine Chapel at the behest of Pope Gregory, headed by Franz Kӧnig, the Archbishop of Vienna. As with before, many split between the conservative candidate Giuseppe Siri – Archbishop of Genoa – while the liberals backed Patriarch of Venice Albino Luciani. The Defender bloc (comprising the communist nation cardinals and most of the American delegation) initially tried to nominate their most outspoken member, Archbishop of Krakow Karol Wojtyła. However, after a series of assassination attempts concerning his outspoken advocacy against the Polish Communist junta (a hardline government), the Cardinal bowed out. The defenders then kept their options open as another compromise choice was likely in the offering, no one else among their members likely to win.

The conclave was rocked on the 5th due to a burst of international news. The Communist government of Argentina – the lone non-European signatory of the Warsaw Pact since West Cuba fell – had been waging a small scale insurgency against anti-communist forces (both democratic and Peronist) since they took power in the mid-Seventies. After a series of Jesuit priests were reported as giving aid and comfort to groups of the rebels, the Security Service arrested Provincial Superior of the Society of Jesus for Argentina Jorge Mario Bergoglio without bond for “counterrevolutionary activities.” The news sent shockwaves throughout the world, especially among the Catholic community. Gregory sent a formal request on behalf of the Papacy for Bergoglio’s release and offered to grant him stay in Rome in exchange for his deportation, but Buenos Aires refused (General Secretary Grishin, under pressure from the hardliners in the Politburo, declined to intervene despite Semichastny’s lobbying and his personal disagreement with the move).

In the Sistine Chapel, the news of Bergoglio’s arrest swung the pendulum decidedly in favor of the defender bloc in the College. Calls for Cardinal Wojtyła to reconsider were deafening, but the Pole remained adamant that he would stay a Cardinal. Afterwards, a new name emerged on Wojtyła’s suggestion, one that hadn’t yet been considered. Cardinal John Krol, the Archbishop of Philadelphia and the de facto leader of the American representatives to the Conclave. Facing pressure from his bloc and high ranking Cardinals, Krol accepted and Wojtyła officially nominated him. Stalwart among the defender bloc and a conservative on doctrinaire issues while a reformer in general, traditional aversion to a non-European Pope was swept aside by the desire to heal divisions and the fear following Bergoglio’s arrest, Cardinals of all factions rallying around Krol.

On the night of September 6th, the white smoke left the Sistine Chapel to herald John Krol’s elevation to the papacy, the first ever pope not originating from Europe since the Dark Ages – and the first from the Western Hemisphere. Taking to the balcony at St. Peter’s Basilica, Krol announced his intention to take the name Leo XIV, after Pope Leo the Great. Associating himself with the pope that had faced down Attila the Hun and emerged victorious, the humble Cleveland native sent a symbolic message through the heart of the world that the Catholic Church was not going to back down from the communist/focoist threat.

On the night of September 6th, the white smoke left the Sistine Chapel to herald John Krol’s elevation to the papacy, the first ever pope not originating from Europe since the Dark Ages – and the first from the Western Hemisphere. Taking to the balcony at St. Peter’s Basilica, Krol announced his intention to take the name Leo XIV, after Pope Leo the Great. Associating himself with the pope that had faced down Attila the Hun and emerged victorious, the humble Cleveland native sent a symbolic message through the heart of the world that the Catholic Church was not going to back down from the communist/focoist threat.

As Stalin had once said, “What armies does the pope have?” Pope Leo couldn’t marshal any direct threat to the Soviet Empire – or its more militaristic allies and satellites now that the USSR was following the neo-Semichastny policies of détente – but as with Billy Graham and the Crusades (even more so considering the Catholic Church’s even greater reach) the soft power possessed by the Bishop of Rome matched the power of even the most massive armies. Leo would, within a month, take a world tour of nations with a significant Catholic population that culminated with a much heralded visit to the Pope’s native United States with huge crowds and an address to a joint session of Congress. Overseen by Cardinal Wojtyła, the Church would pour funds and manpower into spreading and maintaining the faith deep within the heart of the communist bloc, often at great cost to the clergy and missionaries sent.

Christianity wasn’t going down without a fight, another batch of worries plaguing the hardliners in Moscow, Buenos Aires, East Berlin, and Tehran.

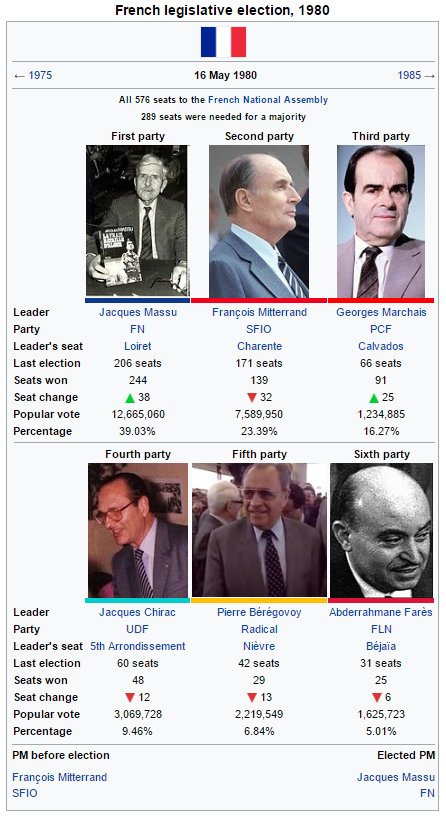

Once again, the jostling of the parties had produced the third election in a row where the government had changed. Increasing it's plurality position, Massu's National Front shared a bare majority with it's coalition partners, the center-right UDF. Under a new leader since D'Estaing retired after the defeat in 1975, Jacques Chirac nonetheless presided over yet another loss of seats as right-wing voters tactically voted for the popular Massu (the UDF's biggest vote share was in metropolitan Paris, where the rural communonationalism of the FN wasn't as popular among the upscale conservatives). Mitterrand's socialists suffered the largest drop in seats, left-wing voters cannibalized by the resurgent communists, who ran a strong campaign focusing on arms reduction and increased worker's rights.

Despite a robust schedule as leader of the opposition in the Assemblee Nationale, Massu was in failing health and merely wanted to retire in 1981. However, the former paratrooper wished to force through the final piece of his legacy in running the National Front, which under his tenure had gone from a minor party in the shadow of Bidault to the largest party on the French right. Namely, his goal was to solidify France's honor as a military power (it couldn't claim superpower status, but the Fourth Republic boasted the third largest military among the NATO powers). A massive naval expansion was passed through the Assembly - putting the Marine Nationale to be larger than the Soviet Navy by 1992 - while the army and air force had their equipment modernized the same way the US and Britain were pursuing. Further mutual defense treaties were signed between France and Spain, Belgium, and the Netherlands, creating a suborganization within NATO (some say Massu was thinking far beyond his time when he sent Foreign Minister Chirac to Madrid for the negotiations). And in his proudest moment, Massu presided over the recreating of the Colonial Paratroopers, tasked with defending France's Community allies from insurgencies.

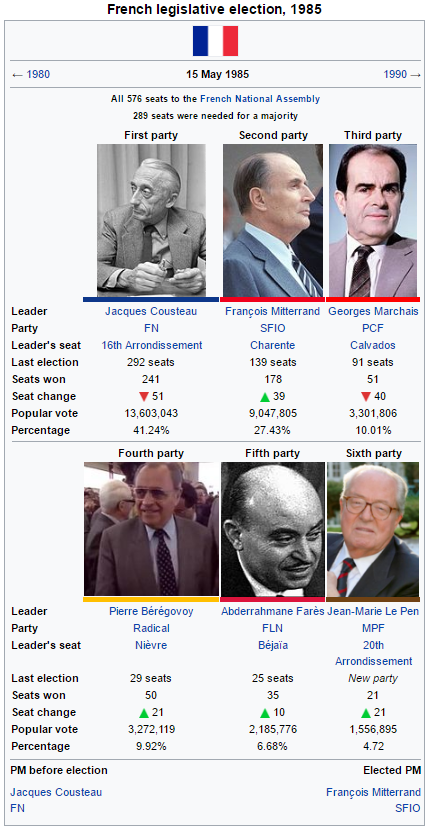

Tired and with his legacy in check, Massu announced his retirement in February 1982. The announcement sent shockwaves through France. The general had been one of the three titans of the new era in the Fourth Republic, along with Georges Bidault and Francois Mitterrand. He would leave a large void in the consciousness of the Republic. One at least a dozen different leaders of the National Front scrambled to fill. The result of the leadership race was... surprising to say the least. After a jockeying process that was far more acrimonious than leadership elections or presidential primaries in other western nations, the winner was a compromise choice. Science and Technology Minister Jacques Cousteau.

Already world famous as an oceanographer - pioneering underwater color filming, a revolutionary concept in teaching the world about the sea - Cousteau was an unlikely choice for Prime Minister of the French Fourth Republic. A former naval diver and a strong defender of Bidault's stabilizing reforms following the Constitutional Crisis of the late 1950s, the political bug had gotten to Cousteau following a move by the First Mitterrand Ministry to cute scientific research grants to bolster spending on other areas of the budget. Speaking out against it and in favor of strong governmental funding of scientific discovery (while still preserving scientific autonomy), Cousteau took the plunge and stood as a candidate in a by-election for an Assembly seat in the conservative 16th Arrondissement. Normally a UDF stronghold in an area the National Front didn't fare well in, Cousteau wished to be in the larger party, and won the election by a large margin. Massu quickly put him in the cabinet as Minister of Science and Technology, owing his public profile. His press conferences calling attention to important scientific research being conducted in the Community were quite popular with the French people, given the simple and endearing manner of speaking in which he was famous for.

Taking office as President of the Council largely as a compromise between the different factions of the party, he was advised by Personal Council Nicholas Sarkozy (a young lawyer whom Cousteau had taken a liking to for representing a business suing his Ministry a year earlier) to take charge quickly or be eaten alive by the more bombastic personalities in the National front such as Defense Minister Helie de Saint Marc and Interior Minister Jean Royer. This Cousteau did, announcing a massive cabinet reshuffle that placed the more moderate wing of the National Front - politicians that weren't part of Massu's clique during the Algerian War - in the dominant position. Some complained to the retired Massu to speak out, but the content man resting under the trees of his countryside villa actually seemed impressed by the oceanographer's fortitude. New leadership had come to the right, and it was just as decisive as the old.

The Cousteau agenda was a striking contrast to the previous policies of the National Front. Of course the primary pillars of nationalism, high defense spending, infrastructure funding, social conservatism. and increased French involvement in the world was kept - doing away with those would mean the extinction of the party. However, Cousteau was far more moderate and fiscally-minded than the "Algiers Clique" which had controlled the party since its inception in the early 1960s, and he charted such a course as President of the Council. In addition to his pet project of broad funding to research and development in the sciences (Cousteau dreamed of France being the leading innovator in this regard), he cut back on several big infrastructure projects he deemed not necessary and passed a modest tax cut. Several state owned businesses were privatized, which he managed to get the public to accept with his friendly and simple speaking style but causing great uproar among the far-right of the National Front.

Knowing his programs would be divisive in the party, Cousteau had set his sights on an ambitions project, to merge the right-wing parties under the National Front banner. doing so would give him a lot more breathing room and moderate the party, drowning out the fringe voices with more metropolitan voters. In a smart move, Cousteau got the blessing of Massu first, basically forcing the Algiers Clique to accede to the merger and giving Chirac cover to do so as well. The UDF was formally absorbed into the National Front in June 1984, giving the sole right-wing party an absolute majority in the National Assembly. However, this had been too much for a few on the right of the party. A group of breakaway local officials led by a Paris Councillor named Jean-Marie Le Pen - and outspoken rightist who often was a thorn in Cousteau and even Massu's side, made famous by a failed hate-speech indictment for a public rant that many said was Holocaust Denial - formed their own party, the Movement for France, to challenge Cousteau in the next elections. Once thought unassailable due to their leader's popularity, the National Front faced it's first ever base problem and the SFIO smelled blood.

The lofty projections for Le Pen's new party did not come to fruition, but many on the right felt that if not for the distraction then Cousteau would have led a united right-wing to victory. The National Front held up well, all things considered. They held onto the vast majority of the former UDF vote under Cousteau's more moderate profile, while only bleeding a small amount of the rural nationalists to Le Pen, who barely cracked .5% in metropolitan Paris. The party merger was one of Cousteau's lasting legacies, cementing the National Front as France's main center-right party and one of the most prominent ones that did not end up adopting Liberty Conservatism as their premier ideology.

The lofty projections for Le Pen's new party did not come to fruition, but many on the right felt that if not for the distraction then Cousteau would have led a united right-wing to victory. The National Front held up well, all things considered. They held onto the vast majority of the former UDF vote under Cousteau's more moderate profile, while only bleeding a small amount of the rural nationalists to Le Pen, who barely cracked .5% in metropolitan Paris. The party merger was one of Cousteau's lasting legacies, cementing the National Front as France's main center-right party and one of the most prominent ones that did not end up adopting Liberty Conservatism as their premier ideology.

Mitterrand had defied the political odds and would take his third non-consecutive term as President of the Council. The Four-party coalition was swept into office, the only party among them to lose seats being the Communists. They had taken a far-left turn due to their opposition to the new government in the USSR, and had been hurt greatly by that stance. Marchais resigned as leader and was replaced by a more Eurocommunist leadership, making Mitterrand's governance far easier as he prepared his cabinet and his agenda for the second half of the decade.

What would be one of the most consequential times in the history of modern France.

With a much friendlier Senate, Whitlam had freer rein to pass his agenda. Papua New Guinea was admitted as a state with equal representation to the rest of Australia, resulting in three new seats proportioned for it during the next general election and serving as a big win for Whitlam’s election promises. The effects of the oil crisis had largely disappeared, and an uptick in economic growth by 1977 largely ended the inflationary crises that plagued Snedden and the Second Whitlam Ministry. The Government used this to shore up the Medibank program, which proved popular with the Australian public.

The majority of the summer months of 1978 were occupied with the debate over the national anthem. Feeling that “God Save the King” was a bit anachronistic, Whitlam proposed that it be changed to something more Australian in nature. Monarchists opposed, but Liberal leader Chipp was also in favor of the proposal so the backlash was neutralized largely at both parties. What would end up the contentious battle was what the new anthem would be. Chipp favored the bland and more traditional “Advance Australia Fair” while Whitlam, in a move that would surprise many, backed the famous bush ballad “Waltzing Matilda.” With Parliament evenly divided on this and his capital gains tax proposal, the Prime Minister called an election for August to obtain a mandate.

No discussion of the Australian Labor Party of the 1970s and 1980s could be made without a rather sizable portion of it devoted to Robert “Bob” Hawke. A minister’s son, his family was quite well connected in the federal Labor Party – his uncle being the Labor Premier of Western Australia. Joining the Australian Council of Trade Unions after receiving his law degree, Hawke rose through the ranks rather quickly and was elected President of the ACTU on a reformist platform (rumor was that several communist-leaning elements supported his candidacy).