No one could deny that the months following November 1956 were good times to be a Republican. After twenty years of Democratic dominance – more or less – the first Republican President since the dark days of the Great Depression had been re-elected in a landslide. States in the south that had been dominated by the Democratic Party such as Texas, Louisiana, and Florida to name three had thrown their weight behind Dwight D. Eisenhower. Though the Senate and the House remained stubbornly Democratic (the one downer to the otherwise jubilant Republicans), margins of 49-47 and 234-201 respectively were decent. A far cry from the massive margins the New Deal Coalition had held during FDR’s time.

All in all, nothing could dampen the celebratory mood in the Grand Old Party’s circles as members hoisted their drinks to four more years of General Ike Eisenhower and Dick Nixon.

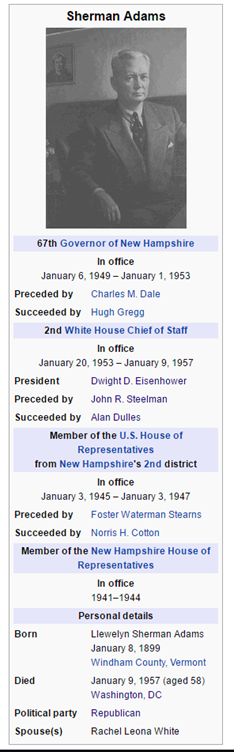

These were all known to Chief of Staff Sherman Adams, the former Governor of New Hampshire and considered the power behind the Eisenhower Administration. With the former Supreme Allied Commander’s military service never truly leaving him in his foray into civilian life, the position had taken an almost military model. Adams had basic control over White House operations, all contact with the President – apart from Nixon and senior cabinet officials – having to go through him first. A warrior for the moderate wing of the GOP, it was common knowledge among the Washington crowd of his importance.

He was the punchline of a widely circulated joke:

Two Democrats were talking and one said "Wouldn't it be terrible if Eisenhower died and Nixon became President?" The other replied "Wouldn't it be terrible if Sherman Adams died and Eisenhower became President!"

With this knowledge, the events of January 9th, 1957 were quite ignominious for someone of his influence. Driving along the darkened streets of the Capitol, blanketed with the winter snow, the weak lights of the vehicle’s headlamps had no way of detecting the slick patch of ice that had formed on the road. Losing friction with the road, the vehicle skidded straight into oncoming traffic and met a truck head on. When police arrived on scene, Sherman Adams was discovered in the driver’s seat, his body bruised and his neck broken. Dead.

Only weeks before the inauguration, the excitement of the new term was clouded with mourning. However, even the high regard the President and his advisors had for Adams didn’t end the obvious need for a Chief of Staff. It wouldn’t besmirch his memory to appoint a successor as soon as possible.

After a series of heated discussions and a closed door meeting between himself and Vice President Nixon, on January 17th, 1957 Eisenhower announced the appointment of longtime Republican donor and distinguished Director of the Central Intelligence Agency Alan Dulles as his new Chief of Staff, passing CIA to the equally competent Richard M. Bissell, Jr. Personally above reproach, Dulles quickly began working with Richard Nixon to push and protect the political goals of the second Eisenhower term. Most things remained the same, but the tension among the varying wings of the party caused by the hard edged Adams were visibly less taxing – a move that would prove a blessing for the Republican Party.

1957 was a grueling year for the Eisenhower Administration. The death of Sherman Adams early on would later be viewed as an inauspicious start, given the many crises that the President and his cabinet would have to endure. Already dealing with the fallout of the Hungarian Revolution and Suez Crisis, Eisenhower began his second term with repairing the image of US strength in the face of an increasingly bombastic Nikita Khrushchev flexing the military muscle of the Red Army. The “Special Relationship” with the United Kingdom began to repair under the new British Prime Minister Harold McMillan, and further aid and military advisors were sent to South Vietnam and other anti-Communist governments facing Eastern Block pressure.

As the year went on, the Administration was rocked by twin punches – one international and one domestic. The case of the “Little Rock Nine” galvanized the attention of the nation, civil rights leaders throwing their support behind the Eisenhower White House for their principled stand in sending soldiers of the 101st Airborne to protect the students, while the segregationist cause rallied behind Governor Orval Faubus. Observers of the drama could reasonably expect Civil Rights issues to dominate much of the nation’s agenda for the near future.

However, the launch of the Sputnik satellite by the USSR truly shook the nation to its core. Having been assured by the actions of Eisenhower and the Pentagon in maintaining a nuclear edge over the Soviet Union, the communist advances into space called all of those efforts into question. Lead by the Special Studies Project headed by Republican Nelson A. Rockefeller (then running for Governor of New York), critics began assailing the President for allowing a so-called “Missile Gap” to be formed in favor of the Russians.

All of this would have likely seriously damaged the administration had it not been for the actions of Vice President Nixon and Chief of Staff Dulles. Coordinating a strategy with the President, Eisenhower forcibly responded to the critics, detailing (to within reason) the true nature of the military situation which showed a large nuclear superiority over the USSR. Policy-wise, increased attention was given to the two US military launch programs, the Navy’s Vanguard and the Army’s Juno. Dulles having convinced Eisenhower beforehand to invest more defense funds in the programs, Project Vanguard successfully launched America’s first satellite into orbit on December 6, 1957 with minimal complications. This was followed by Juno I one month later, both celebrated by the public.

Though America projected a strong front of catching up with the USSR, White House officials understood what was at stake. After signing the act which removed jurisdiction of space exploration from the military to the civilian National Aeronautics and Space Administration, on August 24th, 1958 Eisenhower took the podium of a joint session of Congress and announced America’s goal in the Space Race.

“With the lead possessed by the communists, now is not the time for half measures or incremental gains. America as a nation can accomplish anything, and America does not think small. Therefore, we will go to the moon. We will secure the moon for the cause of Liberty!”

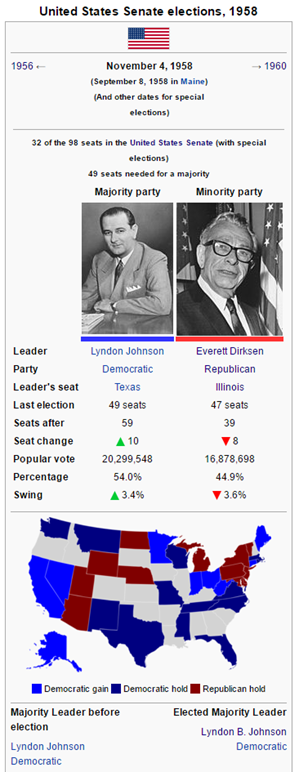

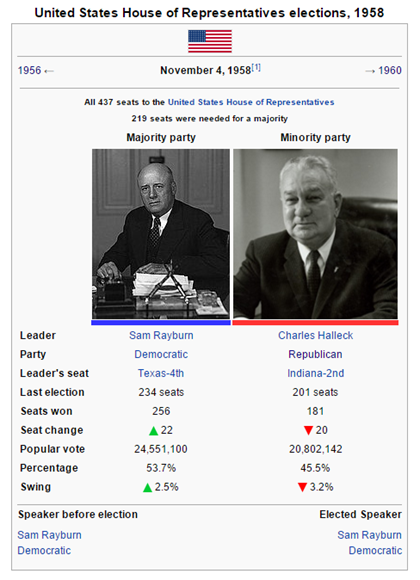

Looking back, it was apparent that the Republicans would lose seats in 1958. A small recession at the beginning of the year had only reminded Americans of Republican association with hard economic times, and right-to-work pushes only angered union voters into high turnout. The senate seats up for election were glut with GOP gains from the 1946 and 1952 landslides, and even the most optimistic of GOPers were predicting modest losses.

In the end, the lack of any major scandals, successful launches of Vanguard and Juno, and the electrifying “Secure the Moon” speech by President Eisenhower staunched the bleeding at just the right time. Richard Nixon later recalled saying to Alan Dulles and his brother – Secretary of State John Foster Dulles – “It’s bad, but not a disaster. Like getting shot in the leg rather than the gut.”

With Hawaii’s entrance into the union in 1959, the Senate held a 60-40 D majority and the House a 255-181 D majority. The Republican seats held on to – along with the wave of new, moderate to liberal democrats – would prove instrumental for the events of the near future.

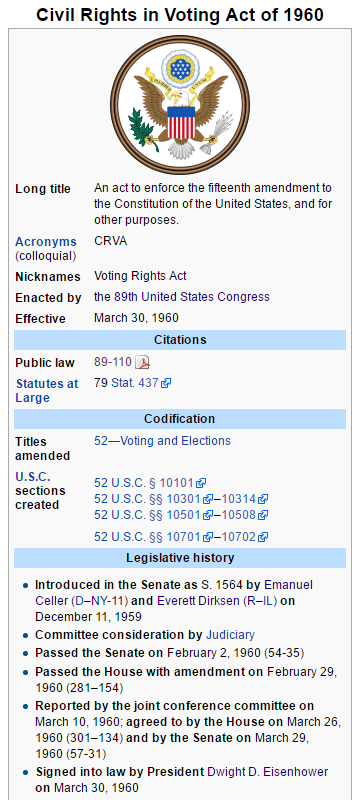

Having engaged in friendly correspondence with the Reverend Martin Luther King Jr, an idea based on the up and coming civil rights leader’s discussing of the lack of black voter participation in the south – due mostly to dramatic cases of voter intimidation by official policies and paramilitary threats. After deliberations with the Dulles brothers, Nixon moved forward with creating a plan to address this. And solidify African-American support for the Republican Party in what was looking to be a close election.

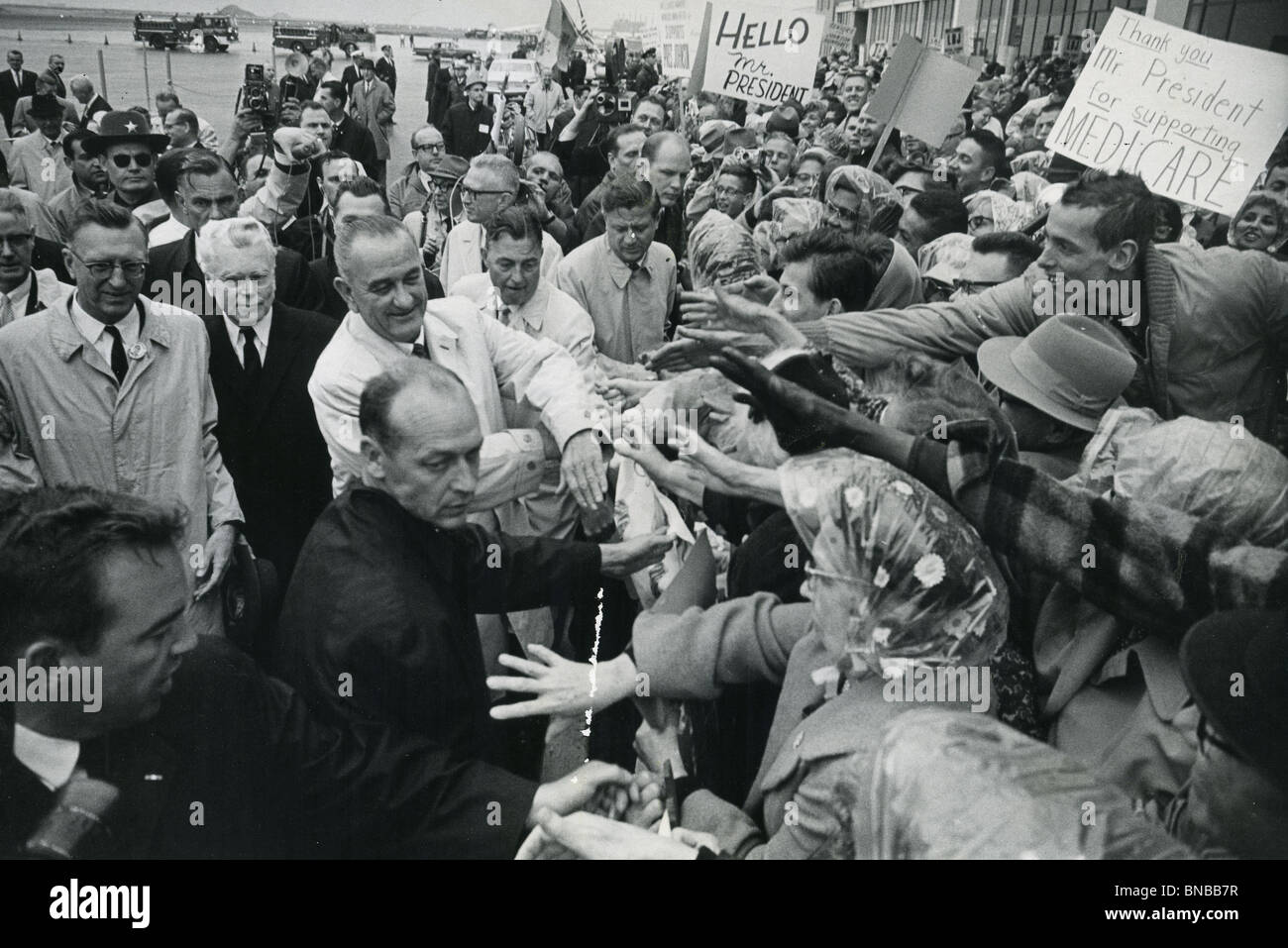

With the blessing of the Troika, President Eisenhower and the Republican leadership pushed for the Civil Rights in Voting Act of 1960, which would basically give the Department of Justice the strict authority to enforce the 15th Amendment nationwide. Senate Majority Leader Lyndon Johnson and Speaker Sam Rayburn, both personally in favor to the legislation, being southern Democrats knew that they would commit political suicide if they voted in favor. While other Civil Rights bills had been previously filibustered to death, Eisenhower had made this the lynchpin of his final two years and lobbied furiously with both congress and the country. Knowing there would be a backlash either way, Rayburn and Johnson split the difference. The bills would be put to a vote, and each would vote against in order to preserve the caucus and prevent another ‘Dixiecrat’ candidacy – considering the African-American vote was coalescing around Nixon, the Democrats couldn’t lose any remaining block of voters.

With the blessing of the Troika, President Eisenhower and the Republican leadership pushed for the Civil Rights in Voting Act of 1960, which would basically give the Department of Justice the strict authority to enforce the 15th Amendment nationwide. Senate Majority Leader Lyndon Johnson and Speaker Sam Rayburn, both personally in favor to the legislation, being southern Democrats knew that they would commit political suicide if they voted in favor. While other Civil Rights bills had been previously filibustered to death, Eisenhower had made this the lynchpin of his final two years and lobbied furiously with both congress and the country. Knowing there would be a backlash either way, Rayburn and Johnson split the difference. The bills would be put to a vote, and each would vote against in order to preserve the caucus and prevent another ‘Dixiecrat’ candidacy – considering the African-American vote was coalescing around Nixon, the Democrats couldn’t lose any remaining block of voters.

The act passed both houses despite narrow majorities of Democrats opposed and a seventeen hour filibuster by Florida Senator George Smathers. Reactions varied from a jubilant crowd headlined by the Rev. Martin Luther King outside the Capitol to violent riots in the Deep South egged on by Orval Faubus, Ross Barnett, and a new face, Alabama Governor George C. Wallace. Civil Rights advocates descended upon the South to begin registering African American voters, most to the benefit of the Republican Party.

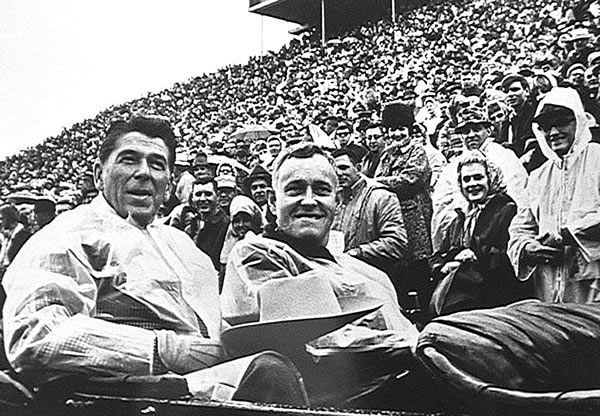

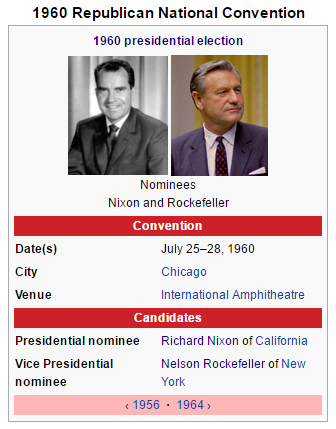

After only a smattering of favorite son votes against him in the primaries, Richard Nixon’s nomination was virtually considered fait accompli. All that remained was who would be chosen as his Vice President. While Nixon was said to have favored former Massachusetts Senator Henry Cabot Lodge Jr due to his considering of foreign policy as the likely sword for which to defeat the Democrats, a day’s deliberations between Murray Choitner, Robert Finch, Alan Dulles, and even President Eisenhower decided that to concede domestic issues was to concede too much to the Democrats – especially considering the massive battle over Civil Rights that was brewing within the Democratic ranks.

Remembering his role as the bridge between the conservative and moderate wings in 1952, Nixon knew he had to unite the two factions of the GOP. One choice would accomplish that beyond a shadow of a doubt: New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller.

Thusly, Finch, Dulles, Senator Kenneth Keating, and John Dulles were asked to approach the popular Rockefeller. After hours of cajoling and reasoned pleas, the formerly reluctant governor accepted Nixon’s offer. Drafting a platform continuing the Eisenhower program, a firm stance against the Soviet Union, and a strong backing of Civil Rights, the convention virtuously unanimously nominated Richard Nixon and Nelson Rockefeller for the Presidency.

Meanwhile, the Democratic nomination didn’t go quite as smoothly. While looked upon as the youthful outsider by the press, the organizational frontrunner was the charming Senator John F. Kennedy of Massachusetts. Owning the support of much of the northeastern establishment and the Labor Unions, his at least making the second place in the convention ballot was guaranteed.

Meanwhile, the Democratic nomination didn’t go quite as smoothly. While looked upon as the youthful outsider by the press, the organizational frontrunner was the charming Senator John F. Kennedy of Massachusetts. Owning the support of much of the northeastern establishment and the Labor Unions, his at least making the second place in the convention ballot was guaranteed.

The main opposition of southern and western delegates pushed Senate Majority Leader Lyndon Johnson to run, the Senator being more than willing but undecided of the timing. Many advisors and the Senator’s own judgement suggested waiting for Kennedy to be bled in the primaries and to push at the convention, but Jim Rowe – his friend and later campaign manager – managed to convince him of the need to run in the primaries and not let Kennedy’s organization build a significant lead.

Coming in second to Kennedy in Wisconsin – edging out Hubert Humphrey and forcing him out – Johnson’s campaign easily built momentum with a narrow win in Illinois after the endorsement of former nominee Adlai Stevenson – who decided not to run – and a strong win in West Virginia. The remaining primaries were split, making the race jump ball at the convention in Los Angeles.

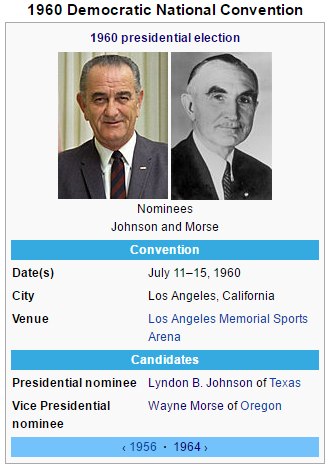

The first ballot showed strength for Kennedy, the Senator sweeping the Northeast and most of the Midwestern delegates. He was denied a majority however, Lyndon Johnson netting most of the remainder but with several favorite son candidates such as Smathers and Oregon Senator Wayne Morse getting decent blocks. Surrogates immediately descended on the small candidate blocks to get the narrow win on the second or third ballots.

After seven ballots the lines barely budged, but when they did they inched slowly to the Massachusetts Senator. What eventually doomed the Kennedy campaign were two factors. Firstly, the Southern delegations decided en mass that Johnson was the more amenable choice than the Catholic, pro-civil rights Kennedy. Secondly, the position of Kennedy’s younger brother Robert as the former’s campaign manager angered influential Teamster’s Union President James “Jimmy” Hoffa. Bobby Kennedy having helped the Senate investigate Hoffa several years before, seeing his chance the bombastic leader of the Teamsters threw himself into pushing delegates for Johnson, cashing favors left and right – along with other, less glamorous methods. The ninth ballot showed both within fifty votes of the other.

The endorsements of Eleanor Roosevelt and Wayne Morse finally cleared the hurdle for Johnson on the tenth ballot, netting him the nomination. Afterwards, Kennedy gave a glowing speech for party unity while Johnson selected Morse as his running mate to undercut Republicans in the West. Flexing their strength, southern Democrats pushed through a softening of the pro-Civil Rights plank introduced by Senator Sam Ervin of North Carolina.

The endorsements of Eleanor Roosevelt and Wayne Morse finally cleared the hurdle for Johnson on the tenth ballot, netting him the nomination. Afterwards, Kennedy gave a glowing speech for party unity while Johnson selected Morse as his running mate to undercut Republicans in the West. Flexing their strength, southern Democrats pushed through a softening of the pro-Civil Rights plank introduced by Senator Sam Ervin of North Carolina.

Polls immediately showed a dead heat, 48-48. A long and arduous campaign lied ahead.

Without the popular former-Supreme Allied Commander on the ballot, the Nixon/Rockefeller ticket were forced back into what amounted to an electoral hole against them. Johnson had the liberal vote, the southern vote, and the unions united behind him out of the convention, and the longtime Oregon Senator Morse gave the Democratic ticket a boost in the Western states, not large electorally but still a major haul.

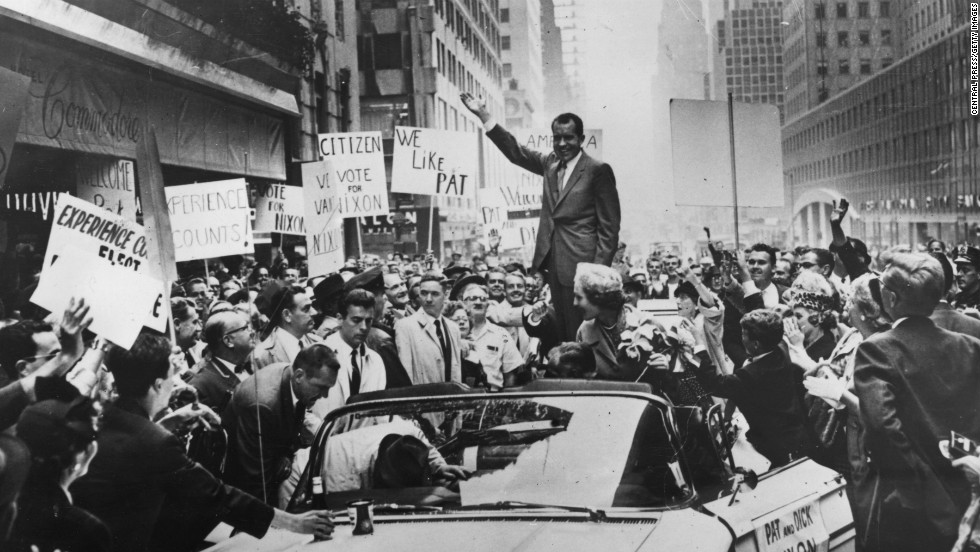

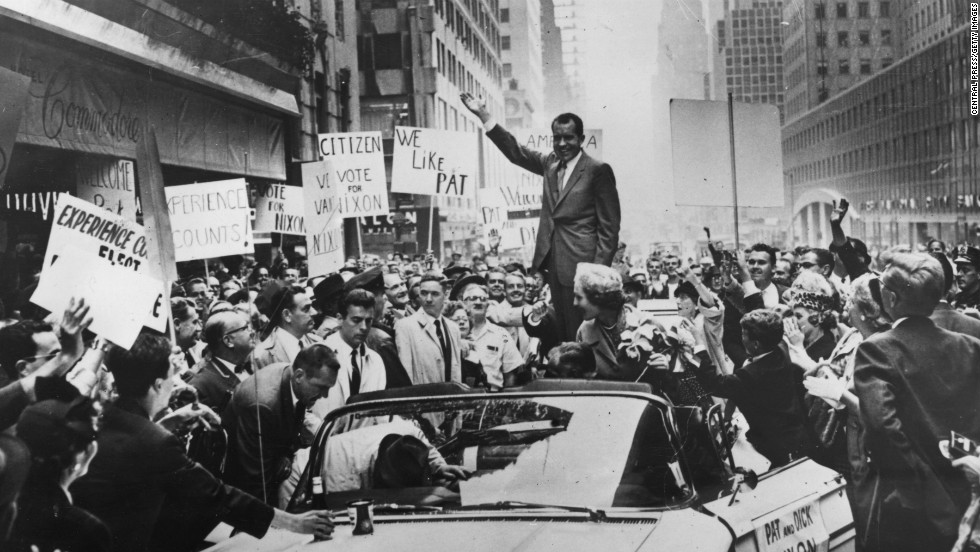

However, Nixon and campaign manager Robert Finch were confident – and thankful not having to run against the charming Kennedy. In facing Johnson, Nixon had youth on his side and couldn’t be outflanked on experience. Over the remaining summer weeks he was focused on a positive campaign, lauding the Eisenhower Administration’s domestic and foreign policy successes. The “Kitchen Debate” where he had famously squared off with Khrushchev was featured prominently in advertising and media appearances. The Republicans were determined to make sure the image of Nixon the strong anti-Communist was maintained. Negative attacks were left to Rockefeller, who leveled his political and oratorical skills directly at Johnson and Morse.

The Democratic nominee had settled into a generally defensive strategy as well, buoyed by Gallup polls showing him up two points on the Vice President. Johnson focused his attention on the Upper South, the electorally rich states of New York and Pennsylvania, and the Midwest (Morse selling the ticket in his stomping grounds west of the Rockies). He attacked the Eisenhower administration for antagonizing the Russians needlessly regarding the Gary Powers incident, which he stated was a national embarrassment.

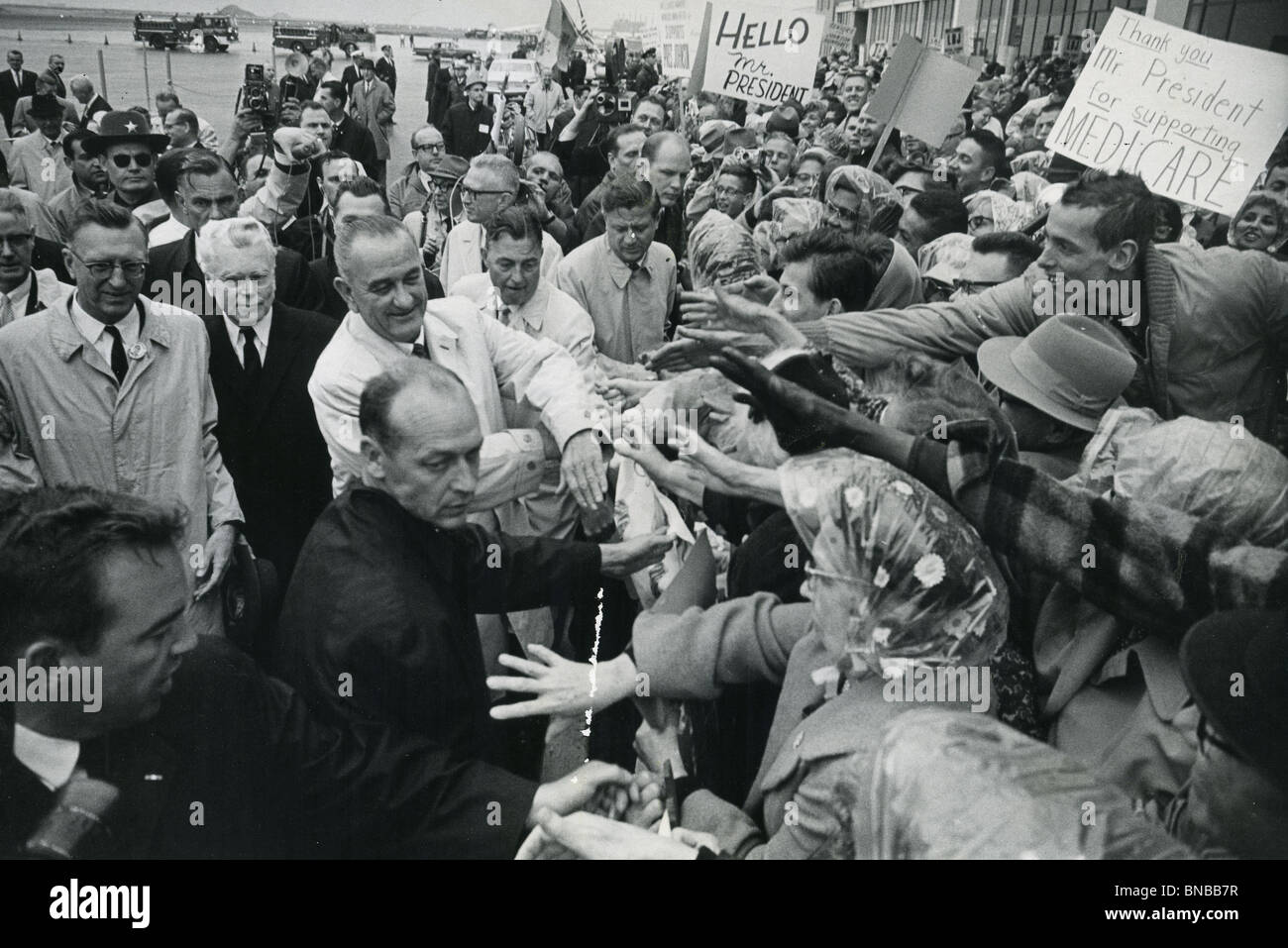

A pitch was made to traditionally Democratic voting blocks that had broken for the popular General Ike, Johnson pushing what Jim Rowe had coined the “Great Society,” a dramatic expansion of what the New Deal had created. Vowing to use his skills acquired as Senate Majority Leader to pass them, “Landslide Lyndon” focused his energy on reminding the card carrying members of the Roosevelt/Truman coalition why they voted Democrat five elections in a row. Standing next to a grinning Jimmy Hoffa, he proclaimed in a major speech to a cheering crowd of Teamsters that a Johnson Administration would declare war on unemployment, lack of health care, and poverty, finishing what FDR started.

To the Republicans, still shaking off the ghost of Herbert Hoover, it became apparent that one couldn’t out government program the New Deal Coalition. The headlines from his speech catapulted Johnson to a six point lead in the next Gallup poll. Even the quick dispatch of President Eisenhower to stump for Nixon couldn’t stem the gloom that was starting to form.

Late September would throw the race on its head however. A strategic gamble had been made before the Convention to attack the Democrats squarely on civil rights. Such was considered by Nixon and Finch to concede nearly the entire south to Johnson – the Texan a natural fit compared to the slick Californian – but the canny observation of Johnson and Morse attempting to straddle the issue loomed too large to ignore. Not a day went by that Nixon wouldn’t boast of his work in passing the CRVA or Rockefeller attacking Johnson and Morse for voting against it and allying with the most hardened segregationists. Earning the enthusiastic endorsement of Martin Luther King, Nixon’s campaign would stand to benefit the most from what would follow.

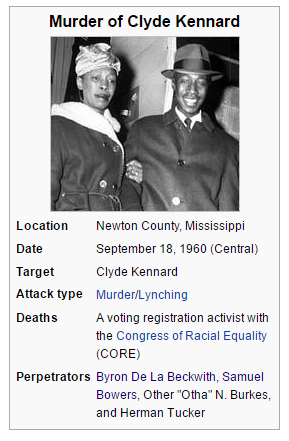

As dawn broke on September 19, the beaten and bruised body of a young black man was discovered hanging from a tree branch in unincorporated Newton County, Mississippi. It was later identified as education and voting rights activist Clyde Kennard of the Congress of Racial Equality. Working to register poor black voters in the heat of the Presidential election, despite efforts of the local sheriff’s department to hush up the brutal lynching hordes of media coverage and civil rights protesters descended on the tiny county seat of Decatur. The perpetrators were later identified to be three rogue Ku Klux Klan members who ambushed Kennard, beat him with baseball bats, and lynched his semi-conscious body, but stonewalling by local officials and the Mississippi state government would put the case in limbo for months and lead to acquittals for the three and their accomplice.

Politically, the crime made headlines around the nation, images of Kennard’s injuries and stills of the ten thousand demonstrators led by CORE founder James Farmer and the Reverend King dominating the front pages of countless newspapers. While Nixon’s civil rights focused campaign was fueled by the sensational murder, it placed the Johnson campaign between a rock and a hard place.

After a tense meeting that Nixon biographer Robert Caro would document thoroughly, both Johnson and Morse reversed course and endorsed key civil rights legislation, condemning the murder and proclaiming that if the state government wouldn’t convict the perpetrators then a Johnson White House would.

When Martin Luther King was arrested by the Newton County Sheriffs on bogus charges of vagrancy and resisting arrest, campaign advisor Robert Kennedy (having joined the Johnson Campaign following the convention) convinced the candidate to phone Coretta Scott King with condolences and an offer of support and Governor Ross Barnett to plead for a pardon of King. The audio tapes were then leaked to the New York Times. The Kings were Nixon supporters, but stated their thanks of Johnson’s kind words and efforts to the press.

Rallies in the northern and western states all heard proclamations of Johnson’s efforts to push civil rights legislation and how his Great Society programs would help black Americans, and in the following weeks it looked like he would ride out the storm.

However, these backtracks angered many southern Democratic officials. Having been Johnson’s strongest backers at the convention, they felt betrayed by his flip flopping on the crucial issue. It still to this day remains a mystery of who masterminded its leakage, but the Washington Post was suddenly given possession of a tape of Johnson in a behind closed doors meeting with his senate colleagues regarding CRVA.

“There goes Tricky Dick [Nixon] pushing his goddamn nigger bill. We’re caught in an –expletive– bind and he knows it. Can’t those –expletive– niggers wait till I’m president to push this bill? Then I’ll have their black asses voting Democratic for a goddamn century!”

In his defense the Senate Majority Leader had been quite angry at the time, but the audio fed into two Nixon campaign barbs of him. One, that he was a soft-segregationist who didn’t truly support even the civil rights bills he voted for – and two, that he was a political chameleon that only took up causes for his own political gain, for which the King call was seen as (it would backfire considerably and lead to Bobby Kennedy’s abrupt departure from the campaign). The fiery Johnson swung back against the accusations hard, but they took their toll. Nixon and Rockefeller smelled blood in the water and struck hard.

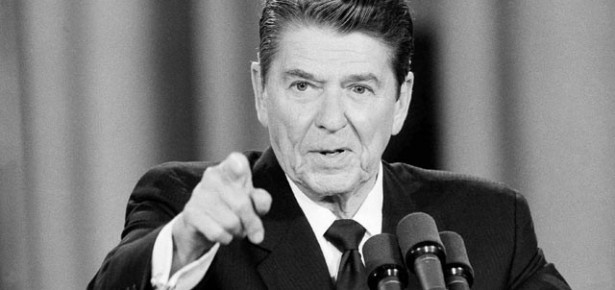

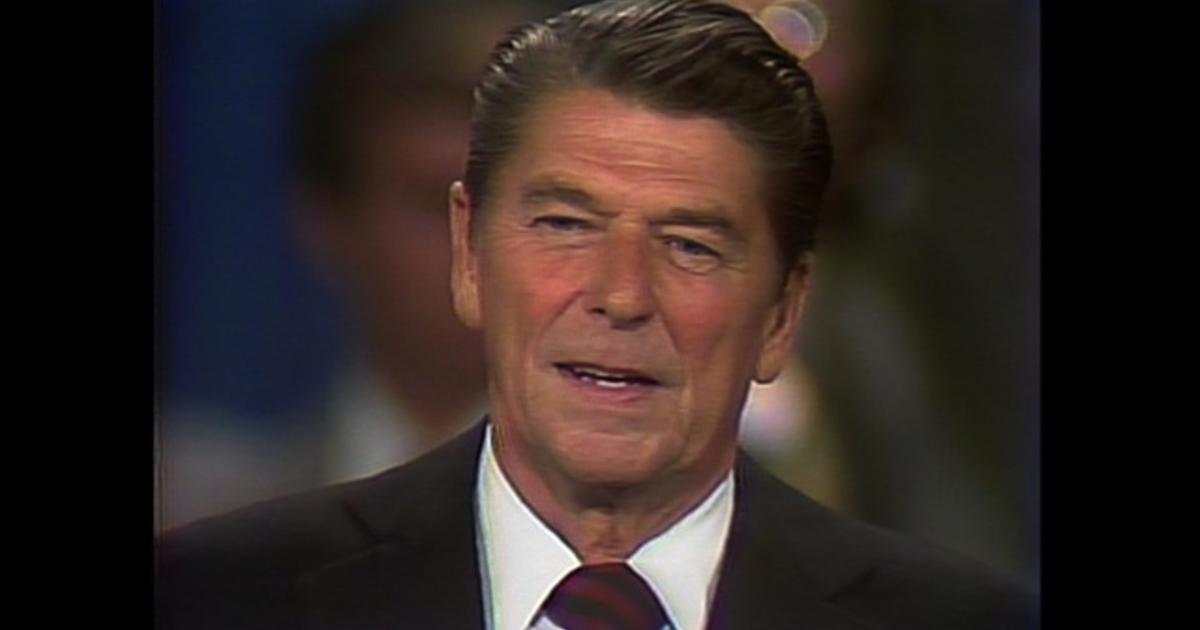

The final straw for the campaign were the televised debates. First of their kind, four had been scheduled beginning with one on domestic policy on October 7th. While Nixon’s team had thought saving the foreign policy debate (Nixon’s strength) for last so as it would gain the highest audience, they would later congratulate themselves for their inadvertent brilliance.

Finch and Choitner took no chances for their candidate, who was leading 49-48 in the early October Gallup poll. He was directed to rest for two days, tan, and rebuild his strength after weeks of tough campaigning while Rockefeller picked up the slack. Shaving off the morning shadow before arriving on stage, he looked both youthful and experienced. Presidential as the papers would call it.

Johnson, however, had made a huge miscalculation. Descending into a flurry of campaigning across the Midwest and Mid-Atlantic states to overcome the civil rights flub, he arrived haggard and with two dark patches under his eyes. The untested medium of television immediately broadcast the differences between the tired and irritable Johnson and the suave and confident Nixon. The Vice President hammered the Senate Majority Leader in easy-going but firm attacks, swatting away at the Great Society programs’ viability and on his duplicity on civil rights. The same bombastic and irascible nature that made him an excellent parliamentary leader came back to bite Johnson, viewers stating that Nixon won the debate convincingly.

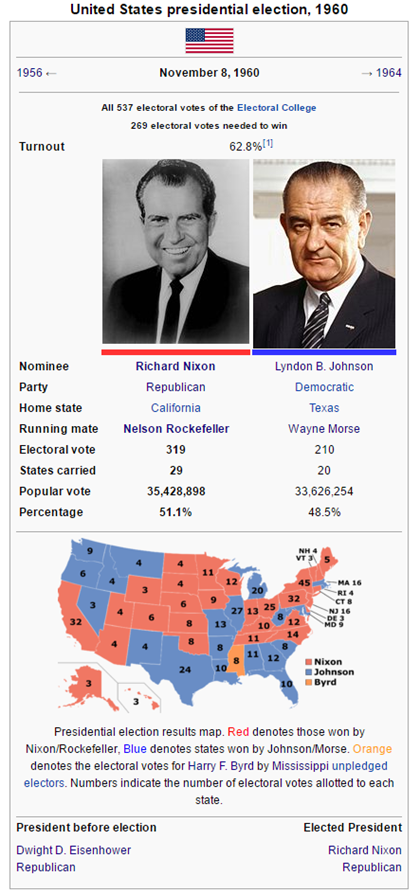

After that, nothing else really mattered. A last minute push by Jimmy Hoffa and George Meany managed to lift Johnson’s numbers a bit, but it was too little too late. The results, to all but the most hardened partisans, were no surprise.

Newly registered black voters broke hard for Nixon, the Vice President winning almost eighty percent of them. Morse managed to swing the northwest for Johnson, while Chicago Mayor Daley’s machine pushed Illinois into the Democratic column. However, the crushing margin among African-Americans and strength among the Nixon/Rockefeller ticket netted much of the Mid-Atlantic and the Upper South, winning the election for Nixon. It was a solid win, the GOP’s third in a row.

Newly registered black voters broke hard for Nixon, the Vice President winning almost eighty percent of them. Morse managed to swing the northwest for Johnson, while Chicago Mayor Daley’s machine pushed Illinois into the Democratic column. However, the crushing margin among African-Americans and strength among the Nixon/Rockefeller ticket netted much of the Mid-Atlantic and the Upper South, winning the election for Nixon. It was a solid win, the GOP’s third in a row.

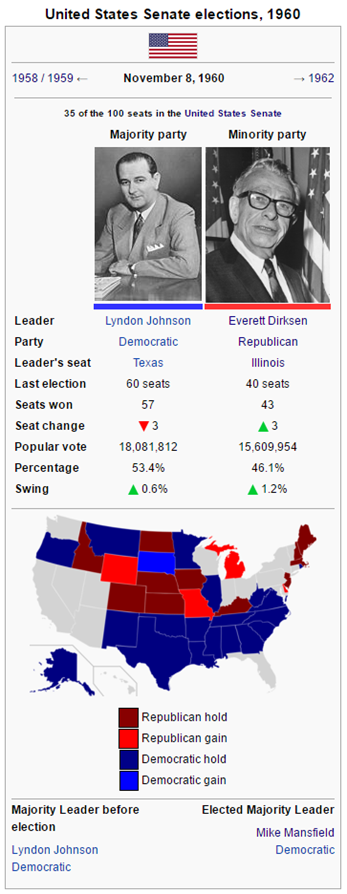

The GOP saw moderate gains in the Senate, Nixon’s convincing win pushing victories in DE, and WY while candidates in MO and MI knocked off sitting Democratic Senators in states Johnson won. However, the Democrats did hold their seats surprisingly well, winning strongly even in states that Nixon carried.

(In Wyoming, GOP Senator-elect Edwin Keith Thomson would die only a month after the election. Democratic Governor John Hickey would appoint himself to the seat, leading the three Republican gains to drop to two).

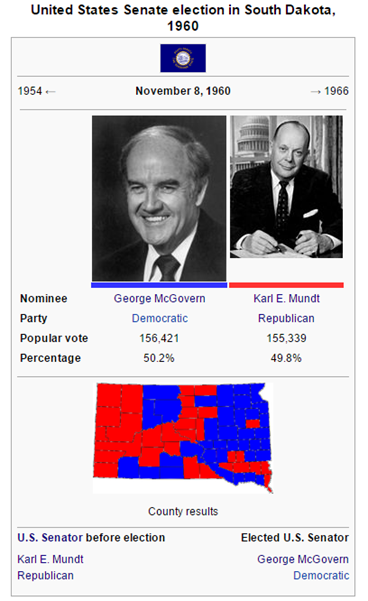

The only GOP loss was in the South Dakota Senate race, where longtime Senator and Nixon ally Karl Mundt lost in a huge upset to ultra-liberal Representative George McGovern. The race was nasty, especially on McGovern’s end, but his bombastic denunciation of Johnson’s civil rights statements and his crusading for rural issues allowed him to overcome the GOP lean of the state and win by only 1,100 votes of over three hundred thousand cast.

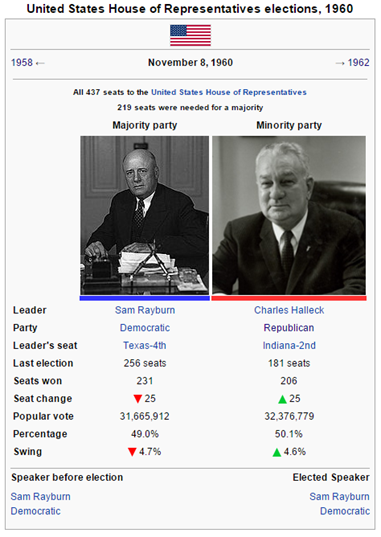

Nixon’s win was welcome to the beleaguered GOP house caucus, pushing them once more above two hundred seats with strong gains in New York, Pennsylvania, the Upper Midwest, and the Upper South canceling out Democrat gains in the West.

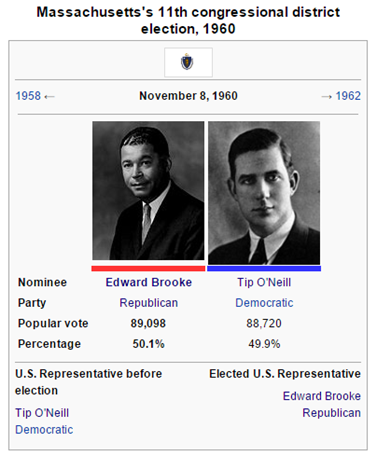

One notable new member was African-American Republican Edward C. Brooke, a tenacious corruption prosecutor who defeated incumbent Democrat Tip O’Neill in the outer Boston 11th district by barely 400 votes. Up till then, the few African-Americans in the house following the New Deal had been inner city Democrats, and many considered his entrance and the enthusiastic support of the Reverend King’s SCLC for Nixon’s candidacy as a sign the tide was turning for black political representation.

One notable new member was African-American Republican Edward C. Brooke, a tenacious corruption prosecutor who defeated incumbent Democrat Tip O’Neill in the outer Boston 11th district by barely 400 votes. Up till then, the few African-Americans in the house following the New Deal had been inner city Democrats, and many considered his entrance and the enthusiastic support of the Reverend King’s SCLC for Nixon’s candidacy as a sign the tide was turning for black political representation.

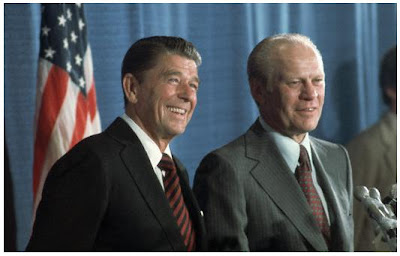

Richard Nixon could now claim a mandate as he prepared to take office as the nation’s 35th President.

All in all, nothing could dampen the celebratory mood in the Grand Old Party’s circles as members hoisted their drinks to four more years of General Ike Eisenhower and Dick Nixon.

These were all known to Chief of Staff Sherman Adams, the former Governor of New Hampshire and considered the power behind the Eisenhower Administration. With the former Supreme Allied Commander’s military service never truly leaving him in his foray into civilian life, the position had taken an almost military model. Adams had basic control over White House operations, all contact with the President – apart from Nixon and senior cabinet officials – having to go through him first. A warrior for the moderate wing of the GOP, it was common knowledge among the Washington crowd of his importance.

He was the punchline of a widely circulated joke:

Two Democrats were talking and one said "Wouldn't it be terrible if Eisenhower died and Nixon became President?" The other replied "Wouldn't it be terrible if Sherman Adams died and Eisenhower became President!"

With this knowledge, the events of January 9th, 1957 were quite ignominious for someone of his influence. Driving along the darkened streets of the Capitol, blanketed with the winter snow, the weak lights of the vehicle’s headlamps had no way of detecting the slick patch of ice that had formed on the road. Losing friction with the road, the vehicle skidded straight into oncoming traffic and met a truck head on. When police arrived on scene, Sherman Adams was discovered in the driver’s seat, his body bruised and his neck broken. Dead.

Only weeks before the inauguration, the excitement of the new term was clouded with mourning. However, even the high regard the President and his advisors had for Adams didn’t end the obvious need for a Chief of Staff. It wouldn’t besmirch his memory to appoint a successor as soon as possible.

After a series of heated discussions and a closed door meeting between himself and Vice President Nixon, on January 17th, 1957 Eisenhower announced the appointment of longtime Republican donor and distinguished Director of the Central Intelligence Agency Alan Dulles as his new Chief of Staff, passing CIA to the equally competent Richard M. Bissell, Jr. Personally above reproach, Dulles quickly began working with Richard Nixon to push and protect the political goals of the second Eisenhower term. Most things remained the same, but the tension among the varying wings of the party caused by the hard edged Adams were visibly less taxing – a move that would prove a blessing for the Republican Party.

As the year went on, the Administration was rocked by twin punches – one international and one domestic. The case of the “Little Rock Nine” galvanized the attention of the nation, civil rights leaders throwing their support behind the Eisenhower White House for their principled stand in sending soldiers of the 101st Airborne to protect the students, while the segregationist cause rallied behind Governor Orval Faubus. Observers of the drama could reasonably expect Civil Rights issues to dominate much of the nation’s agenda for the near future.

However, the launch of the Sputnik satellite by the USSR truly shook the nation to its core. Having been assured by the actions of Eisenhower and the Pentagon in maintaining a nuclear edge over the Soviet Union, the communist advances into space called all of those efforts into question. Lead by the Special Studies Project headed by Republican Nelson A. Rockefeller (then running for Governor of New York), critics began assailing the President for allowing a so-called “Missile Gap” to be formed in favor of the Russians.

All of this would have likely seriously damaged the administration had it not been for the actions of Vice President Nixon and Chief of Staff Dulles. Coordinating a strategy with the President, Eisenhower forcibly responded to the critics, detailing (to within reason) the true nature of the military situation which showed a large nuclear superiority over the USSR. Policy-wise, increased attention was given to the two US military launch programs, the Navy’s Vanguard and the Army’s Juno. Dulles having convinced Eisenhower beforehand to invest more defense funds in the programs, Project Vanguard successfully launched America’s first satellite into orbit on December 6, 1957 with minimal complications. This was followed by Juno I one month later, both celebrated by the public.

“With the lead possessed by the communists, now is not the time for half measures or incremental gains. America as a nation can accomplish anything, and America does not think small. Therefore, we will go to the moon. We will secure the moon for the cause of Liberty!”

Looking back, it was apparent that the Republicans would lose seats in 1958. A small recession at the beginning of the year had only reminded Americans of Republican association with hard economic times, and right-to-work pushes only angered union voters into high turnout. The senate seats up for election were glut with GOP gains from the 1946 and 1952 landslides, and even the most optimistic of GOPers were predicting modest losses.

In the end, the lack of any major scandals, successful launches of Vanguard and Juno, and the electrifying “Secure the Moon” speech by President Eisenhower staunched the bleeding at just the right time. Richard Nixon later recalled saying to Alan Dulles and his brother – Secretary of State John Foster Dulles – “It’s bad, but not a disaster. Like getting shot in the leg rather than the gut.”

Even heavily Republican Northeastern and Midwestern states saw Democratic gains. Several major losses included that of noted conservative John W. Bricker (R-OH) and that of former Senate Minority Leader William F. Knowland (R-CA), who’s attempt to switch offices with Governor Goodwin Knight led to both being lost to the Democrats.

However, narrow holds in NY, MI, WY, MD, and NJ kept the party afloat. Conservative Republican J. Bracken Lee won in a landslide over Frank Moss in Utah, while Eisenhower’s popularity netted one of AK’s senate seats and stemmed the bleeding in the House.

However, narrow holds in NY, MI, WY, MD, and NJ kept the party afloat. Conservative Republican J. Bracken Lee won in a landslide over Frank Moss in Utah, while Eisenhower’s popularity netted one of AK’s senate seats and stemmed the bleeding in the House.

------------------------------

Vice President Richard M. Nixon was considered by most to be a shoo in at the GOP Convention. The Californian was instrumental in the last three years, along with Alan Dulles and Herbert Brownell, in shaping the President’s agenda (nicknamed the ‘Troika’ by the Press).

Having engaged in friendly correspondence with the Reverend Martin Luther King Jr, an idea based on the up and coming civil rights leader’s discussing of the lack of black voter participation in the south – due mostly to dramatic cases of voter intimidation by official policies and paramilitary threats. After deliberations with the Dulles brothers, Nixon moved forward with creating a plan to address this. And solidify African-American support for the Republican Party in what was looking to be a close election.

The act passed both houses despite narrow majorities of Democrats opposed and a seventeen hour filibuster by Florida Senator George Smathers. Reactions varied from a jubilant crowd headlined by the Rev. Martin Luther King outside the Capitol to violent riots in the Deep South egged on by Orval Faubus, Ross Barnett, and a new face, Alabama Governor George C. Wallace. Civil Rights advocates descended upon the South to begin registering African American voters, most to the benefit of the Republican Party.

After only a smattering of favorite son votes against him in the primaries, Richard Nixon’s nomination was virtually considered fait accompli. All that remained was who would be chosen as his Vice President. While Nixon was said to have favored former Massachusetts Senator Henry Cabot Lodge Jr due to his considering of foreign policy as the likely sword for which to defeat the Democrats, a day’s deliberations between Murray Choitner, Robert Finch, Alan Dulles, and even President Eisenhower decided that to concede domestic issues was to concede too much to the Democrats – especially considering the massive battle over Civil Rights that was brewing within the Democratic ranks.

Remembering his role as the bridge between the conservative and moderate wings in 1952, Nixon knew he had to unite the two factions of the GOP. One choice would accomplish that beyond a shadow of a doubt: New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller.

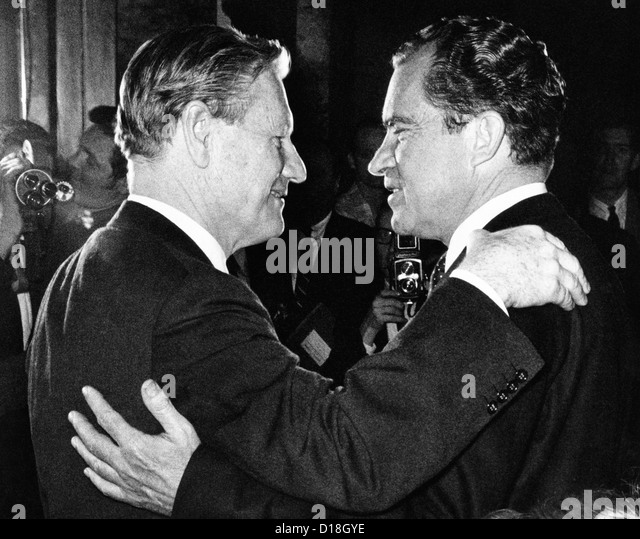

Thusly, Finch, Dulles, Senator Kenneth Keating, and John Dulles were asked to approach the popular Rockefeller. After hours of cajoling and reasoned pleas, the formerly reluctant governor accepted Nixon’s offer. Drafting a platform continuing the Eisenhower program, a firm stance against the Soviet Union, and a strong backing of Civil Rights, the convention virtuously unanimously nominated Richard Nixon and Nelson Rockefeller for the Presidency.

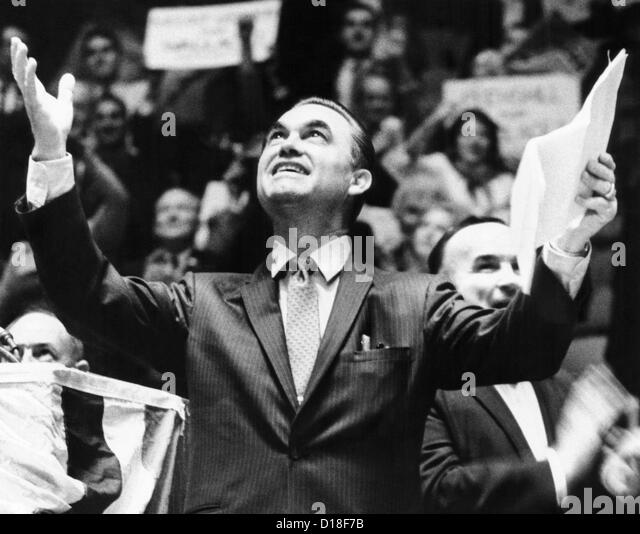

The main opposition of southern and western delegates pushed Senate Majority Leader Lyndon Johnson to run, the Senator being more than willing but undecided of the timing. Many advisors and the Senator’s own judgement suggested waiting for Kennedy to be bled in the primaries and to push at the convention, but Jim Rowe – his friend and later campaign manager – managed to convince him of the need to run in the primaries and not let Kennedy’s organization build a significant lead.

Coming in second to Kennedy in Wisconsin – edging out Hubert Humphrey and forcing him out – Johnson’s campaign easily built momentum with a narrow win in Illinois after the endorsement of former nominee Adlai Stevenson – who decided not to run – and a strong win in West Virginia. The remaining primaries were split, making the race jump ball at the convention in Los Angeles.

The first ballot showed strength for Kennedy, the Senator sweeping the Northeast and most of the Midwestern delegates. He was denied a majority however, Lyndon Johnson netting most of the remainder but with several favorite son candidates such as Smathers and Oregon Senator Wayne Morse getting decent blocks. Surrogates immediately descended on the small candidate blocks to get the narrow win on the second or third ballots.

After seven ballots the lines barely budged, but when they did they inched slowly to the Massachusetts Senator. What eventually doomed the Kennedy campaign were two factors. Firstly, the Southern delegations decided en mass that Johnson was the more amenable choice than the Catholic, pro-civil rights Kennedy. Secondly, the position of Kennedy’s younger brother Robert as the former’s campaign manager angered influential Teamster’s Union President James “Jimmy” Hoffa. Bobby Kennedy having helped the Senate investigate Hoffa several years before, seeing his chance the bombastic leader of the Teamsters threw himself into pushing delegates for Johnson, cashing favors left and right – along with other, less glamorous methods. The ninth ballot showed both within fifty votes of the other.

Polls immediately showed a dead heat, 48-48. A long and arduous campaign lied ahead.

Without the popular former-Supreme Allied Commander on the ballot, the Nixon/Rockefeller ticket were forced back into what amounted to an electoral hole against them. Johnson had the liberal vote, the southern vote, and the unions united behind him out of the convention, and the longtime Oregon Senator Morse gave the Democratic ticket a boost in the Western states, not large electorally but still a major haul.

However, Nixon and campaign manager Robert Finch were confident – and thankful not having to run against the charming Kennedy. In facing Johnson, Nixon had youth on his side and couldn’t be outflanked on experience. Over the remaining summer weeks he was focused on a positive campaign, lauding the Eisenhower Administration’s domestic and foreign policy successes. The “Kitchen Debate” where he had famously squared off with Khrushchev was featured prominently in advertising and media appearances. The Republicans were determined to make sure the image of Nixon the strong anti-Communist was maintained. Negative attacks were left to Rockefeller, who leveled his political and oratorical skills directly at Johnson and Morse.

The Democratic nominee had settled into a generally defensive strategy as well, buoyed by Gallup polls showing him up two points on the Vice President. Johnson focused his attention on the Upper South, the electorally rich states of New York and Pennsylvania, and the Midwest (Morse selling the ticket in his stomping grounds west of the Rockies). He attacked the Eisenhower administration for antagonizing the Russians needlessly regarding the Gary Powers incident, which he stated was a national embarrassment.

A pitch was made to traditionally Democratic voting blocks that had broken for the popular General Ike, Johnson pushing what Jim Rowe had coined the “Great Society,” a dramatic expansion of what the New Deal had created. Vowing to use his skills acquired as Senate Majority Leader to pass them, “Landslide Lyndon” focused his energy on reminding the card carrying members of the Roosevelt/Truman coalition why they voted Democrat five elections in a row. Standing next to a grinning Jimmy Hoffa, he proclaimed in a major speech to a cheering crowd of Teamsters that a Johnson Administration would declare war on unemployment, lack of health care, and poverty, finishing what FDR started.

To the Republicans, still shaking off the ghost of Herbert Hoover, it became apparent that one couldn’t out government program the New Deal Coalition. The headlines from his speech catapulted Johnson to a six point lead in the next Gallup poll. Even the quick dispatch of President Eisenhower to stump for Nixon couldn’t stem the gloom that was starting to form.

Late September would throw the race on its head however. A strategic gamble had been made before the Convention to attack the Democrats squarely on civil rights. Such was considered by Nixon and Finch to concede nearly the entire south to Johnson – the Texan a natural fit compared to the slick Californian – but the canny observation of Johnson and Morse attempting to straddle the issue loomed too large to ignore. Not a day went by that Nixon wouldn’t boast of his work in passing the CRVA or Rockefeller attacking Johnson and Morse for voting against it and allying with the most hardened segregationists. Earning the enthusiastic endorsement of Martin Luther King, Nixon’s campaign would stand to benefit the most from what would follow.

As dawn broke on September 19, the beaten and bruised body of a young black man was discovered hanging from a tree branch in unincorporated Newton County, Mississippi. It was later identified as education and voting rights activist Clyde Kennard of the Congress of Racial Equality. Working to register poor black voters in the heat of the Presidential election, despite efforts of the local sheriff’s department to hush up the brutal lynching hordes of media coverage and civil rights protesters descended on the tiny county seat of Decatur. The perpetrators were later identified to be three rogue Ku Klux Klan members who ambushed Kennard, beat him with baseball bats, and lynched his semi-conscious body, but stonewalling by local officials and the Mississippi state government would put the case in limbo for months and lead to acquittals for the three and their accomplice.

Politically, the crime made headlines around the nation, images of Kennard’s injuries and stills of the ten thousand demonstrators led by CORE founder James Farmer and the Reverend King dominating the front pages of countless newspapers. While Nixon’s civil rights focused campaign was fueled by the sensational murder, it placed the Johnson campaign between a rock and a hard place.

After a tense meeting that Nixon biographer Robert Caro would document thoroughly, both Johnson and Morse reversed course and endorsed key civil rights legislation, condemning the murder and proclaiming that if the state government wouldn’t convict the perpetrators then a Johnson White House would.

When Martin Luther King was arrested by the Newton County Sheriffs on bogus charges of vagrancy and resisting arrest, campaign advisor Robert Kennedy (having joined the Johnson Campaign following the convention) convinced the candidate to phone Coretta Scott King with condolences and an offer of support and Governor Ross Barnett to plead for a pardon of King. The audio tapes were then leaked to the New York Times. The Kings were Nixon supporters, but stated their thanks of Johnson’s kind words and efforts to the press.

Rallies in the northern and western states all heard proclamations of Johnson’s efforts to push civil rights legislation and how his Great Society programs would help black Americans, and in the following weeks it looked like he would ride out the storm.

However, these backtracks angered many southern Democratic officials. Having been Johnson’s strongest backers at the convention, they felt betrayed by his flip flopping on the crucial issue. It still to this day remains a mystery of who masterminded its leakage, but the Washington Post was suddenly given possession of a tape of Johnson in a behind closed doors meeting with his senate colleagues regarding CRVA.

“There goes Tricky Dick [Nixon] pushing his goddamn nigger bill. We’re caught in an –expletive– bind and he knows it. Can’t those –expletive– niggers wait till I’m president to push this bill? Then I’ll have their black asses voting Democratic for a goddamn century!”

In his defense the Senate Majority Leader had been quite angry at the time, but the audio fed into two Nixon campaign barbs of him. One, that he was a soft-segregationist who didn’t truly support even the civil rights bills he voted for – and two, that he was a political chameleon that only took up causes for his own political gain, for which the King call was seen as (it would backfire considerably and lead to Bobby Kennedy’s abrupt departure from the campaign). The fiery Johnson swung back against the accusations hard, but they took their toll. Nixon and Rockefeller smelled blood in the water and struck hard.

The final straw for the campaign were the televised debates. First of their kind, four had been scheduled beginning with one on domestic policy on October 7th. While Nixon’s team had thought saving the foreign policy debate (Nixon’s strength) for last so as it would gain the highest audience, they would later congratulate themselves for their inadvertent brilliance.

Finch and Choitner took no chances for their candidate, who was leading 49-48 in the early October Gallup poll. He was directed to rest for two days, tan, and rebuild his strength after weeks of tough campaigning while Rockefeller picked up the slack. Shaving off the morning shadow before arriving on stage, he looked both youthful and experienced. Presidential as the papers would call it.

Johnson, however, had made a huge miscalculation. Descending into a flurry of campaigning across the Midwest and Mid-Atlantic states to overcome the civil rights flub, he arrived haggard and with two dark patches under his eyes. The untested medium of television immediately broadcast the differences between the tired and irritable Johnson and the suave and confident Nixon. The Vice President hammered the Senate Majority Leader in easy-going but firm attacks, swatting away at the Great Society programs’ viability and on his duplicity on civil rights. The same bombastic and irascible nature that made him an excellent parliamentary leader came back to bite Johnson, viewers stating that Nixon won the debate convincingly.

After that, nothing else really mattered. A last minute push by Jimmy Hoffa and George Meany managed to lift Johnson’s numbers a bit, but it was too little too late. The results, to all but the most hardened partisans, were no surprise.

The GOP saw moderate gains in the Senate, Nixon’s convincing win pushing victories in DE, and WY while candidates in MO and MI knocked off sitting Democratic Senators in states Johnson won. However, the Democrats did hold their seats surprisingly well, winning strongly even in states that Nixon carried.

(In Wyoming, GOP Senator-elect Edwin Keith Thomson would die only a month after the election. Democratic Governor John Hickey would appoint himself to the seat, leading the three Republican gains to drop to two).

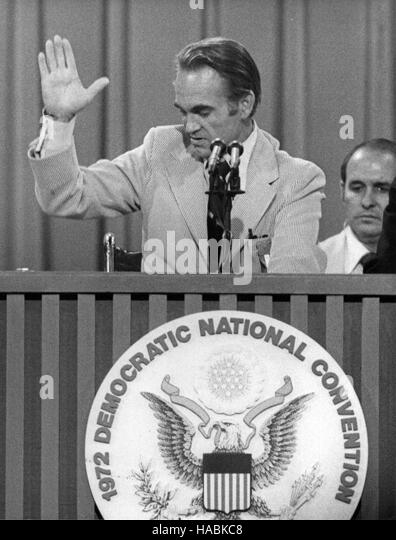

The only GOP loss was in the South Dakota Senate race, where longtime Senator and Nixon ally Karl Mundt lost in a huge upset to ultra-liberal Representative George McGovern. The race was nasty, especially on McGovern’s end, but his bombastic denunciation of Johnson’s civil rights statements and his crusading for rural issues allowed him to overcome the GOP lean of the state and win by only 1,100 votes of over three hundred thousand cast.

Nixon’s win was welcome to the beleaguered GOP house caucus, pushing them once more above two hundred seats with strong gains in New York, Pennsylvania, the Upper Midwest, and the Upper South canceling out Democrat gains in the West.

Richard Nixon could now claim a mandate as he prepared to take office as the nation’s 35th President.