Bundy’s Reaction: Foreign Policy from Mid-1997- election day 1998

Throughout this period, America cut back on defense drastically. The Americas and the Pacific were seen as America’s own backyard, so to call Bundy completely isolationist was false, but America was really hunkering down and focusing on domestic policies.

Neutrality Policy

Shortly after the war has started, Bundy passed the Buchanan-Lamm act which allowed American firms to sell to both sides of the war provided they sign liability papers absolving the US government from any protection of their goods and acknowledging the dangers associated with trading with powers at war. While most companies started trade with the Concordat, trade with both sides deepened the pockets of many companies. This infamously included the Pinkerton security company. After negotiations through the Swiss with both factions, it was agreed that the US government would not interfere with private negotiations between combatant nations and private firms and that ships flying the American flag were to be considered non-combatants for all intents and purposes. The same would apply to British allies, namely: Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Malaysia, and Ghana, along with other minor Commonwealth nations outside of the war. (Sierra Leone and the West Indies Federation were not wholly neutral in the conflict, both siding with the Concordat, though neither country ended up involving themselves in the conflict). Most aid would be done on a “cash and carry” basis, though with the added element that companies, union representatives, and individual agents would absolve themselves of US Government protection or responsibility. Thus if any US citizens died, it would be understood that they knew the risks. This would receive less opposition than proposed Neutrality Acts, which Bundy felt would keep the US from escalating its involvement.

Meanwhile, Rockefeller Republicans and wealthy whites preferred the US side with the Concordat and even wanted to renew the old NATO alliance. The Concordat was the lesser of two evils in the conflict, they said, reminding the American people that all members of the Concordat were liberal democracies, while in the Entebbe Pact only Kenya could say this about their political system. That being said, Americans were not hungry to join the war, especially so soon after World War III. In fact in Europe itself, popular protests against the war ground many cities in France to a halt and Bundy hatched what was called the “Pontius Pilate Policy” by Democrats, as a compromise. While most of the combatant nations made their own heavy arms for security reasons, they lapped up American commercial products for less glamorous supplies. These opportunities would give US firms long-lasting customer relationships and marketing knowledge in many areas. Hershey, for example, was the official “dessert provider” for Somalian MRE’s. It expanded beyond chocolate and into more tropically appropriate offerings like Sambusas, and Sabayads, which would become popular in other non-warring markets. Other more exotic options like Goulash and Appams served to boost the morale of many soldiers in the Entebbe Pact with little delights. Uganda also bought GM trucks, and GM engineers gained experience how to design a car for the tough and varied conditions of fighting in Africa. The one company that benefited the most from the war though, was pro-Concordat: Enron.

Jeff Skilling, founder of Enron, 6-month temporary NBA commish, and Commerce Secretary, used his position to secure oil contracts to supply the Concordat during the Great Southern War. Pre-war, he had used his connections in the administration, and according to some, a lot of corruption. Enron made a mind financing oil and natural gas development in the balkanized Russian nations, using corrupt practices to overcome many of the smaller, corrupt governments. As a result of both factors, Enron skyrocketed to one of the top 10 energy companies in the world, seeing its stock skyrocket. Since Skilling’s continuing connections to Enron could never be proven by Entebbe Pact intelligence, nothing came of it, and Bundy, and the USA, were off the hook, for now at least.

In one of the crueler twists of history, the Hershey Corps now ubiquitous Sambusas came originally from MRE's.

Military Budget

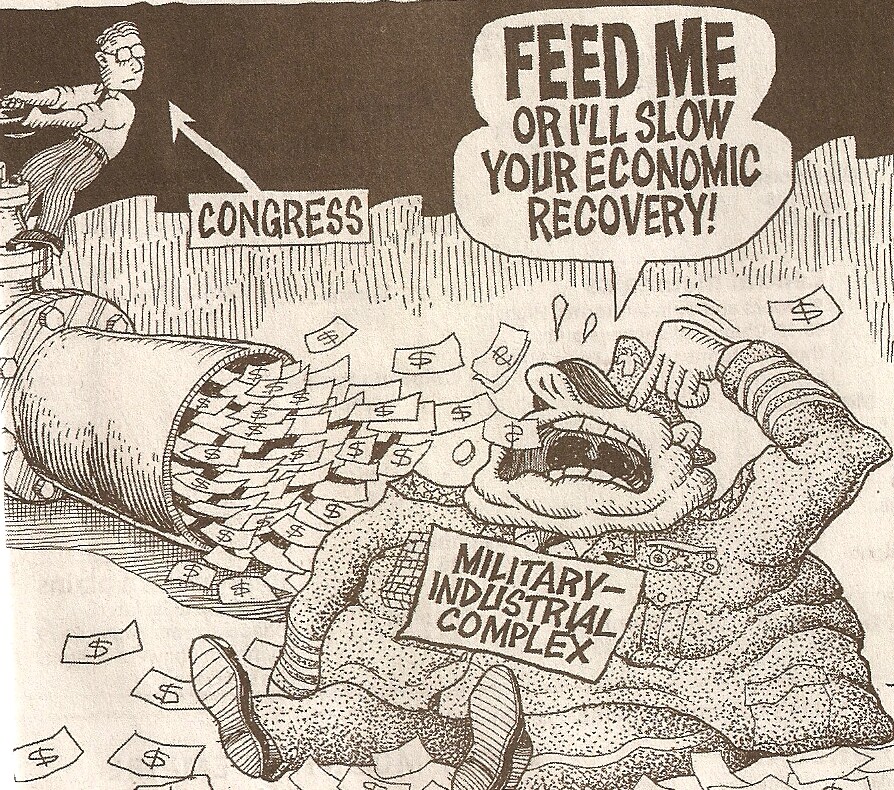

Bundy’s main priority in the military budget was to “narrow” American foreign policy and focus on the Americas and Indo-Pacific, where American threats were the greatest. He also wanted to “cut off” the Military Industrial Complex, a “Boogeyman” that Progressives, especially Barbara Jordan, had encouraged Perot to attack as the source of various maladies (with varying degrees of truth). Bundy knew that to win reelection, he’d have to prove that he was not beholden to such a force. He would fight this big business as if it was nothing. He reminded many Americans of the days of Eisenhower and his warnings against the military-industrial complex, and told them it needed to be cut down to size.

A Minaprogressive political cartoon from the time that increasingly resonated with Bundyites

He sold almost the entire force of B-1 bombers to the Japanese, who were more than willing to take the relatively obsolete forces. Bundy also destroyed 200 warheads in the nuclear arsenal-primarily aircraft based weapons. The Army Reserves were capped at 170,000. The National Guard would be capped at 270,000, but special forces would be increased by 20,000. Bundy wanted to ensure that intelligence of a future threat would be as good as possible and that if foreign leaders needed to “accidently crash into a brick wall”, as some eloquently put it, they’d do so. The number of carriers and associated air groups in the navy was reduced to seven. All commands in Europe and Africa, outside of the newly created “British Command”, meant to be a forward base incase the US would have to return to Europe in wartime, were retired. The only bases in Europe or Africa without major withdrawals was in East Anglia, which became a nearly exclusive US military base. Roy Mason had insisted on a US presence in England, and while Bundy was reluctant, he obliged in order to get more drastic cuts in the middle east from wavering Pro-UK Senators including Senator Jerry Springer. PM Mason also had developed a good relationship with Bundy, and his approval ratings spiked from this key victory. domestic congressional commission was created, with the goal of eliminating usefulness army bases on the 6-5-5 basis: 6 army bases, 5 navy bases, and 5 air force bases. The only current overseas operation was in Siberia, and due to recent stability, two thousand troops were put on reserve from the region. The total number of active military troops was reduced to 800k.

Moreover US foreign aid was cut by 20% (primarily the aid that went to Africa, Western Europe, and MENA), with 60% of these funds diverted to a small increase in domestic GMI welfare payments, 15% going into an increase in subsidies/loans for the IDFC, and 25% going to pay the deficit. Many noted that by this point, most of the rebuilding funds had been paid towards already. Most US Aid was directed towards Venezuela, Colombia, the Philippines, and various ex-Soviet States. Bundy knew the power of foreign aid, and wanted to control it under his “imperial visage”, as critics would put it. Many were furious that the humanitarian vision of Kennedy, Eisenhower, and Rumsfeld would be swept away but their complaints were drowned out in a GMI increase and inflation-attacking tax cut.

In addition, a senatorial commission on defense waste was instituted. Its first recommendation was an audit of the Pentagon. This hadn’t been done since before WWIII, and as chairman Mike Castle said “it's about damn time”. It would save taxpayers billions of dollars although many communities would grow angry at losing their pork projects.

Many defense-industry focused communities, especially in California, would cite 1997 as “the year the music died”. While Rumsfeld and Iacocca had already cut military spending from WWIII, it had remained relatively high until now. Many communities centered around the defense industry would slowly, but ever increasingly, feel the pinch of America’s withdrawal in their pocketbook. Cheap housing and a good business climate would mitigate the effect in those areas not solely dependent on defense, but a storm was brewing.

Bundy was ruthless in his pursuit of fighting inflation and more importantly, beating the Progressive Party in winning over western pacifist voters. Being a Washingtonian, Bundy took winning the Northwest and Mountain West for the Republican Party as a personal quest. Moreover, more communonationalist voters, though not communinationalist experts, were OK with a less adventurous America.

Many wondered, with war on the horizon, whether Bundy’s moves were wise. Internationalist critics would call Bundy “Reckless”, arguing that a strong defense would deter war, but Bundy would harken back to the last three world wars and “reject the failed policy of pre-war buildup as a path to peace” Bundy stated flatly: “on no circumstances will I let the Military Industrial Complex drag the good people of these United States into war for purposes that do not relate to the most vital parts of our nation's security”. Moreover, Bundy said that unilateral disarmament would be a statement of good faith for the cause of peace. This antagonized the more Rumsfeld-Esque elements of the party, a fact Bundy acknowledged with the last major foreign pre-Midterm foreign policy move.

Recognition of the Armenian Genocide

Sometime in the Middle of the Great Southern War, Bundy officially recognized the Armenian Genocide after Owen Bieber put a bill on the floor to do so, forcing Bundy’s hand, in order to win Armenian-American support in Michigan. Bundy announced his support for the bill, which passed easily. Bundy gave a speech acknowledging this commemoration in the Rose Garden with the Armenian President, an official guest of honor, and the president of the Armenian-American foundation. The speech was a resounding success. It made Bundy look less “mean” in the eyes of the public and fostered US-Armenian relations as Armenia unilaterally removed import quotas and tariffs on US imports (the few there were).

Protesters gathered in DC on the date of recognition to raise awareness and thank Bundy

This moved infuriated Turkey, who considered withdrawing their diplomatic delegation to D.C., but decided against it. Turkey would increase existing tariffs on US goods and reduce the number of allocated travel visas for US tourists. Many worried that this move would hurt US-Timurid relations, but in many ways, Romney cited the opposite. By acknowledging that the US would not tolerate the darker side of Pan-Turanism in the past, Bundy forced the regime in the Timurid Empire to suppress these impulses, especially amongst academics, and moved the regime to a more moderate path internationally. This would necessitate restrictions on academic freedom, which lead to much questioning in academic circles of Timurid policy.

Critics would argue that his move was purely political. It did give Bundy near complete support in the small Armenian-American population and raise his standing amongst Greek-Americans (who were increasingly reticent of the new regime in Turkey), though it would hurt his support amongst Turkish-Americans and contribute to Republicans increasingly sour results amongst South Asian Muslims (due in part to Speaker Modi’s rise).

Bundy, however, saw it as a testament “to the fundamentally moral dimension of my foreign policy” (this quote would be parodied on many talk shows). He said that American moral and economic might would better serve peace than military might. It also shed the view that America was becoming completely detached from world affairs, which he knew would hurt Republicans in more urban and cosmopolitan districts, though it helped in the minaprogressive mountain west and midwest.

Overall, Bundy’s “great retreat”, or as his academic admirers prefer, “great repositioning”, helped the US navigate through some very muddy waters.