NoEver watched A Face in the Crowd?

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

New Deal Coalition Retained: A Sixth Party System Wikibox Timeline

Storm in the Kremlin

“Instead of one great Stalin, a quarter of the world is ruled by six little ones.”

-Lech Walesa-

At 5:00 AM on the 21st of December, Moscow media outlets suddenly went dark, causing intelligence and foreign offices across the west to take notice. Not long afterwards, diplomats and embassy officials in the Soviet capitol reported T-80 tanks of the Tamanskaya Motor Rifle and Kantemirovskaya Tank Division rolling through the streets towards Red Square and the major government buildings. President Rumsfeld was getting ready for bed when informed by his staff on the development only thirty minutes later – right as TASS was back on the air. Bathrobe draped over his pajamas, the President watched as a robotic newscaster announced that General Secretary Yakovlev had resigned effective immediately due to “Concerns over a recently diagnosed case of hypertension and atherosclerosis.” TASS then stated that KGB Chairman Vladimir Kryuchkov would be assuming the direction of the country “To secure the center of World Socialism from counter-revolutionary elements.”“Instead of one great Stalin, a quarter of the world is ruled by six little ones.”

-Lech Walesa-

Rumsfeld’s reply to this news was too obscene for future transcribers to include on the WH taping system without muting it.

The prospect of great bloodshed was what had kept Kryuchkov and the others from acting until now, but in a meeting just before May Day 1986 they decided it was time. Planning commenced, shrouded in secrecy to avoid certain death. For the plan to succeed, it was imperative that the KGB, Red Army, and Interior Ministry were secure under allies. Being the former Chairman of the KGB, Vladimir Semichastny had been able to use his legend to prevent a coup in the past, but after nearly a decade Yuri Andropov, Viktor Chebrikov (deeply involved in the plot while retired), and Kryuchkov had quietly replaced key elements within the organization with forces loyal to them. Interior controlled a massive number of domestic security troops, but the Minister was Grigory Romanov, a noted hardliner and vicious opponent of Yakovlev and Mikhail Gorbachev. He was easily brought in as a fellow plotter. As for the Red Army, Chief of the General Staff Marshal Sergey Akhromeyev became an enthusiastic member, one of the most dissident voices against Yakovlev’s removing ground divisions from abroad. All the pieces in place, the plotters waited for the day to arrive.

Commencement of the coup was initially scheduled for a few days after New Year, but the plotters moved it to the 21st after Semichastny scheduled a vacation to Yalta and Gorbachev scheduled on a state visit to Bulgaria – Interior Minister Romanov and the Bulgarian Government both took steps to strand the two figures out of the way, paving the path for the entire plan to be launched. Coordinating with paratroopers under General Alexander Lebed, the two mobile divisions swarmed the capitol, securing the city and setting up defensive checkpoints in case forces loyal to the moderates interfered. From the Defense Ministry and STAVKA Yazov and Akhromeyev issued orders to the various Red Army Front commanders to stand down, sharing a report about German nuclear testing as a reason to prepare for potential NATO attack. The report was fiction, but played perfectly to Soviet fears regarding Germany and served its purpose to keep the Red Army facing shadows while the main action played out.

Led by General Viktor Karpukhin (a veteran of the assassination of Josip Tito), the KGB Alpha and Vympel Groups were the crack special forces of the Soviet security forces. Made sure to be completely loyal to Kryuchkov, the most important portion of the coup was coordinated by Chebrikov and led by Karpukhin. The first move was an assault on the Kremlin, the defending Taman Guards largely standing down – though some didn’t and had to be dispatched by force – and General Secretary Yakovlev taken. Other detachments hit the residences and offices of key Yakovlev allies and important civil servants, capturing the main ones and killing several underlings that were too dangerous to leave alive as well as sowing chaos among the reformers. Many of the republic party apparatuses secured such as Pugo’s Latvia and Volodymyr Shcherbytsky’s Ukraine were fully behind the coup, the KGB paramilitaries advancing and detaining dozens of potential coup opponents and leaving the parties in control of the hardliners. After a lightning morning, enough of the Soviet state was under their control to allow the plotters to announce themselves to the world as the State Committee on the State of Emergency, announce Yakovlev’s resignation, suspend the new Glasnost rights, and declare martial law across the nation.

A problem then manifested itself. What was the Committee to do with all those it arrested? Traditional Soviet doctrine dictated that there be a few show trials and executions, along with far more executions in the dank basements of Lefortovo Prison. Most of the underlings and coup supporters begged the Committee to undertake this, and it was the subject of great discussion within its meetings. It was a narrow decision, but Kryuchkov ultimately broke in favor of not conducting a repeat of Stalin’s purges. Maintaining internal order was too important, he felt, and decided on a polyglot course of imprisonments, house arrests (including Yakovlev), and reassignments to out of the way positions where they would still be useful but not a danger in the slightest. Thus, bloodshed was averted. Averted by the skin of its teeth, but averted nonetheless.

-------------------------

Much as the western media would characterize the December Pustch as a bloody coup reminiscent of Stalin, the restraint ordered by the Committee resulted in rather little bloodshed – the bloodiest incident being a riot between Interior Ministry troops and nationalist protestors in Tashkent, seventeen dying when the soldiers fired into the crowd. However, such wasn’t the truth in the Soviet Union’s allies. In nations controlled by more moderate governments, the KGB had coordinated with conservative elements within the communist parties to launch coups of their own, which were often bloody. It was far worse in the Warsaw Pact nations already controlled by hardliners. As soon as the Committee declared itself the sole government of the USSR, security services went to work.

Poland, the general election a year before having brought much of the opposition out of the shadows, was by far the bloodiest example. General Jaruzelski had been the first allied leader brought into the coup, and the tanks had barely entered Red Square before Solidarity leaders were being rounded up and summarily executed. Everyone within his government that backed the elections were arrested and charged with treason, Jaruzelski dissolving the Sejm (as well as any vestiges of democracy or non-authoritarian rule in the Polish state). Effectively, Stalinist rule with him as the complete dictator was the new order, no dissent to be tolerated.

The vast majority of Solidarity’s leadership was dead or imprisoned, with its lower echelons going back underground – however, the biggest get had eluded Polish authorities to Jaruzelski’s anger and consternation. Lech Walesa had been tipped off of the coming raid in which he’d likely be shot in a dank basement outside of Warsaw. Donning a hat and simple workman’s outfit, he escaped into the streets and booked for the Vatican Embassy. After a conversation with Cardinal Wojtyła and Pope Leo, he was granted official asylum despite the Polish demanding that he be handed over. Knowing that Walesa wasn’t safe anywhere in Europe (the Italian Communists being even more under Moscow’s thumb following the departure of Enrico Berlinguer and the Eurocommunist Freyists), Pope Leo began a negotiation with Secretary of State Dick Cheney, who offered asylum in the United States for the Polish leader.

Not all the Communist Bloc found hardline elements taking over or consolidating control following the December Coup. In Romania, Nicolae Ceausescu and the Securitate – utilizing the deep sources the powerful intelligence agency possessed within the KGB and Soviet Defense Ministries – quickly made sure the entire Romanian Communist hierarchy was composed of moderate loyalists. The Committee wasn’t fooled by all the sudden “heart attacks,” “brain aneurysms,” “health retirements,” and “extended tropical vacations” that popped up in Bucharest, but were unwilling to risk a Hungary or Yugoslavia popping up to suck Red Army resources. Ceausescu was safe and still committed to the Soviet Union by Romania’s geography, unwilling to break away for the same reason as the Soviets refrained from pushing for regime change.

This wasn’t repeated in the Chinese sphere (nor in Mozambique or Somalia, where Samora Michel and Siad Barre began sending feelers to Entebbe and Kinshasa). Jiang Qing, meeting privately with Li Peng and Deng Xiaoping, determined that China needed to distance itself from Moscow and preserve its new trading relationship with the west. Most governments within China’s sphere of influence agreed, though North Korea resisted “Giving up the struggle against the imperialist swine.” This ended when Supreme Leader Kim il-Sung was found dead of an apparent stroke in his countryside palace. He was replaced by his 47-year-old son Kim Jong-Il, far more tractable and under the Chinese thumb. Moscow was dismayed by the newfound Sino-Soviet split, but had expected this and prepared accordingly.

Reaction in the West was a mix between worried posturing and abject terror. Anti-communist protestors took to the streets across the western world, riots breaking out in several major cities when anti-war counterprotestors and the occasional communist mob mixed it up with them. Waves of panic buying were the norm, bomb shelters and duck and cover drills popularized during the Portuguese Crisis suddenly taking off again. All of this took a massive hit on the financial markets – the Dow crashed 600 points right out of the gate on the day of the coup, London, Paris, and Tokyo plunging an average of 21% of their value as well. After a six-hour teleconference with several NATO leaders, President Rumsfeld led the pack by announcing a week-long suspension of trading to ride out the storm, seeking to preserve the economy at the high point it had been at. Such efforts would largely work, but the market panic exemplified how the western public viewed the developments across the Iron Curtain.

---------------------------

At the end of January, the Committee had felt enough time had passed – and their control was secure enough – to dissolve itself and reconstitute the Politburo. Each of the committee members were granted a key position by General Secretary Kryuchkov to hold on the Politburo Defense Council (effectively the sole governing body for the creation of national policy). Demichev was granted the Defense Ministry, Yazov moved laterally to control Industry. Pugo was put in charge of Interior (with Romanov taking over as Party Secretary), Pavlov made Chairman of the Moscow Party to replace the purged Boris Yeltsin. Yanayev rounded off the list to become Chairman of the Council of Ministers. Together, they ran the Soviet Union amongst themselves, importing their allies to run the other ministries and bloodless purging the Yakovlev allies to “count trees” in Siberia. Kryuchkov brought Viktor Chebrikov out of retirement to lead an even more powerful KGB, which was given even more oversight over the Red Army. Finance Minister Eduard Shevardnadze and Chairman of the Presidium Yegor Ligachyov were booted in favor of Yuri Maslyukov and Volodymyr Shcherbytsky respectively, Nikolai Ryzhkov taking over the crucial Agriculture and Petroleum portfolios at the same time. Veteran military officer Sergey Sokolov, who had masterminded the military modernization of the Red Army, was made Supreme Commander of the Red Army by Demichev and Akhromeyev in a move causing great fear and apprehension in the West.

In the end, the only Politburo members remaining of the old ruling guard of reformers were Minister without Portfolio Semichastny (too well-loved by the people to purged), Minister of Foreign Affairs Gorbachev (kept on due to having a good rapport with the West, deemed necessary after removing Yakovlev), and Chairman of the Cultural Affairs Bureau Solzhenitsyn (not considered a threat). In addition, neutral-leaning Chairman of the Kazakh Party Dinmukhamed Kunayev had no real reason to be dismissed, having largely played off both sides though following the coup he began siding more and more with the remaining reformers. However, with Yakovlev resting in his private Dacha outside of Moscow, there was little the four could do to stop the former Committee from implementing their vision of Soviet greatness, one that was already making the world tremble.

Last edited:

Or WWIII or greatest crisis ever, like the end of Cold War in Broken America. Let's hope that if this escalate, it will be a World in Conflict style war and not a Fallout one.Damn. Why do I envision World War III right around the corner?

I sympathize with Rummy here.Rumsfeld’s reply to this news was too obscene for future transcribers to include on the WH taping system without muting it.

Bookmark1995

Banned

I sympathize with Rummy here.

I think anyone would react that way if a bunch of desperate fanatics seized power in a nuclear armed nation.

I wonder if the nationalist movements in the Soviet Union are going to get covert aid from the CIA.

Who says they aren't already?I think anyone would react that way if a bunch of desperate fanatics seized power in a nuclear armed nation.

I wonder if the nationalist movements in the Soviet Union are going to get covert aid from the CIA.

Who says they aren't already?

This is going to get bloody.

A Growing Problem with Ethiopia

A furious Idi Amin Dada slammed his fists on the table in his office, making the two assembled men shutter.

"Damn hardliner Communist bastards!" exclaimed Amin. "And to think I was going to make a state visit to Moscow to form a trade deal with Yakovlev."

The Ugandan Minister of Defence, General Yoweri Museveni* spoke up.

"And what is that?" asked Amin.

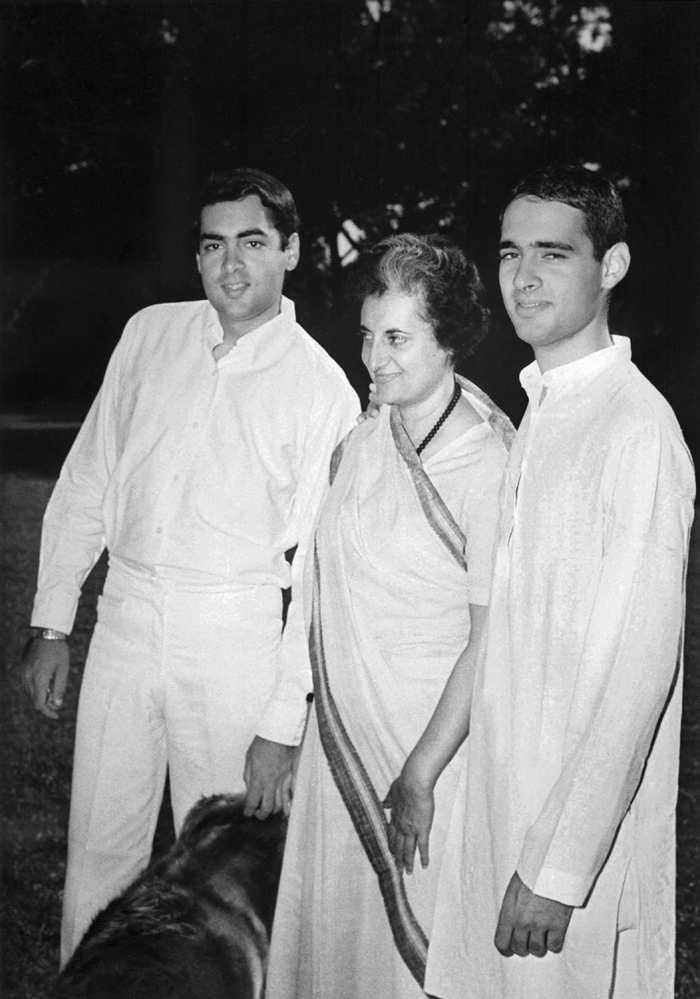

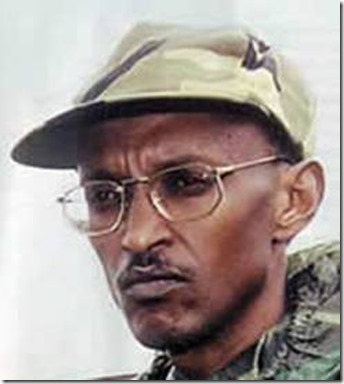

"Well sir, External Affairs have reported that there are increasing border skirmishes between the Kenyan and Ethiopian armies." said Museveni. Amin turned his attention to the director of the Ministry of External Affairs, Paul Kagame.

"Yes sir. Addis Ababa seems to think that since there is now a hardliner regime in Moscow that they can move against their enemies." said Kagame.

"What in the hell is Mengistu thinking?!?!" exclaimed Amin. "Does he want war with the Entebbe Pact?!"

"It's a possiblity. He has been getting extremely paranoid since the Rwanda War." said Museveni. Amin sat back in his chair and sighed. He hesitated for a bit then spoke.

"I'll call Mobutu and Savimbi...and Pretoria probably. See what they think before I contact Obama." said Amin. Uganda's strongman wanted to get Zairean, Angolan, and South African opinions on the matter before speaking with Obama Sr. who would be more likely to advocate for a full-scale war than the others would considering that these border skirmishes are happening right on his doorstep. Amin wasn't in the mood for conducting a war right now. "Well at least Samora Michel and Siad Barre are coming to their senses."

"Yes sir, both the Mozambicans and Somalians seem to be sending a clear message of their intentions to outright join the Pact." said Kagame with a weak smile.

-----------------------------------------------

* = Museveni was the founder of the Front for National Salvation (FRONASA) rebels before he defected to the Ugandan Army during the Rwanda War of the late 1970s when it was apparent that Tanzania and the anti-Amin Ugandan rebels would lose the war. Since his defection, he has risen through the ranks of the army to become not just a general but the Minister of Defence.

Last edited:

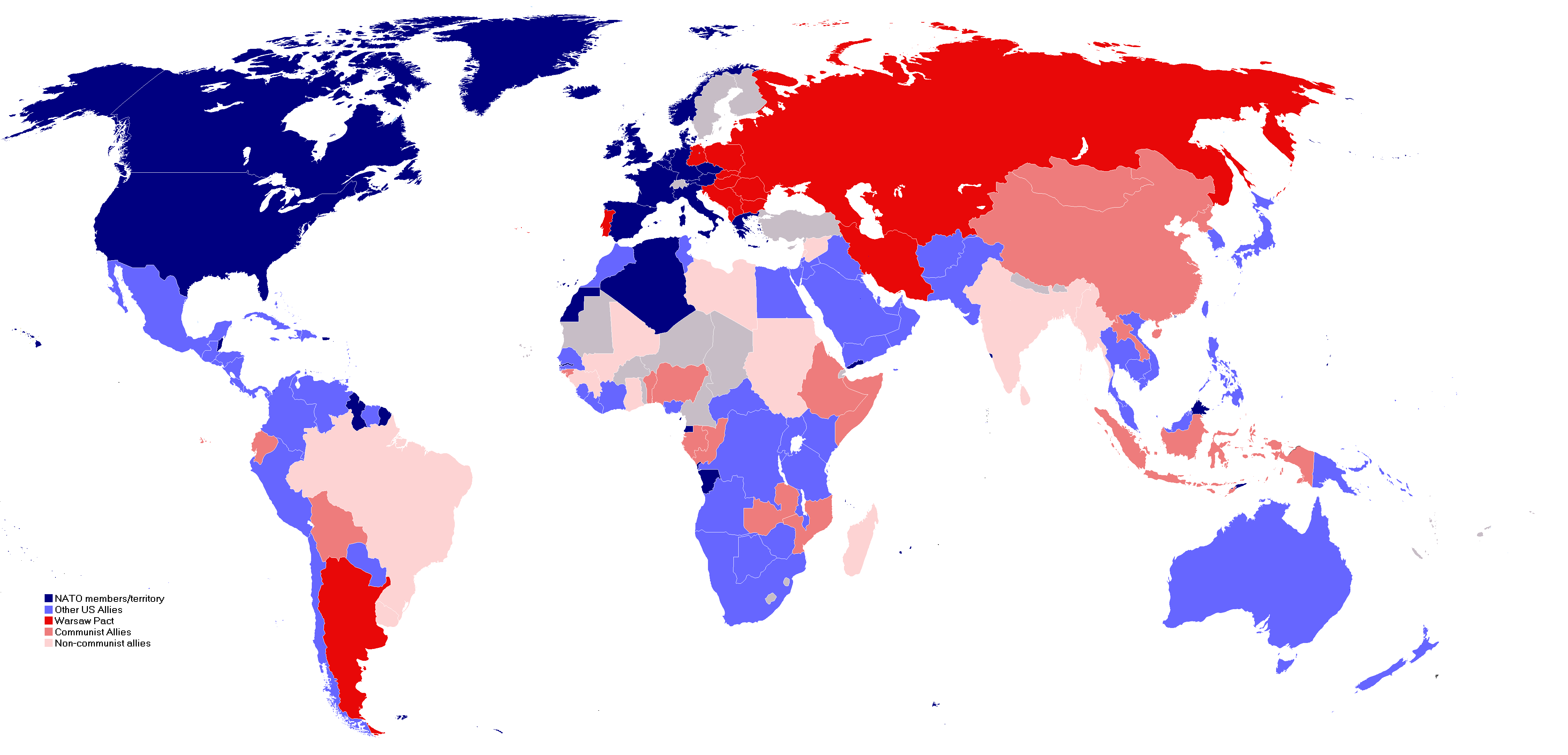

I updated the world map to show what the world looked like at the time of the Soviet Coup.

TheCongressman stated in an older post that it was it was made an integral part of Britain along with Guyana, Belize, The Gambia, and Aden.

Wait a minute...Vietnam was unified under Saigon's banner? I dont remember that.

The US and South Vietnam conquered the North in 72 under Wallace.Wait a minute...Vietnam was unified under Saigon's banner? I dont remember that.

Share: