You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Nation On A Hill: A Timeline by Xanthoc

- Thread starter Xanthoc

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 50 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 2: The Purification Part #20: Purity Flag Interlude #10: The Many Rebellions of France Part #21: Do You Hear the People Scream? Map Interlude: Europe and North America in 1760 Part #22: Divided We Stand, United We Fall Part #23: Dressed to Oppress Part #24: Sleeping Tiger, Clashing DragonsRangers never die, they're just missing in action.

Y'know I almost used that exactly, but 1. couldn't find when the term Missing in Action came into common use, and 2. felt like that would've been a bit too on the nose.

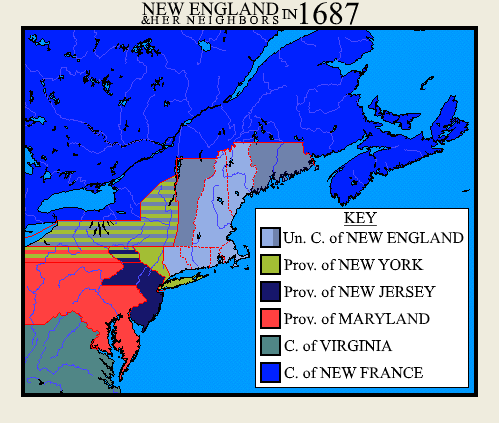

Map Interlude #2: New England 1687

Map Interlude #2: New England 1687

"Given the destruction of the City of New York, and given the ensuing collapse of law and order within the Province of New York, that was then restored by forces of the New English Militia, the Maryland Volunteer Militia, and the New Jersey Militia, it was no surprise that Yorkish territorial sovereignty would begin to fall apart as well. The Treaty of Concord had not just New English and native delegates, but those of New York as well, namely members of the militia that had become the effective government after the majority of its public officials perished in fire. These men recognized that their colony would be in dire straits, and that their fellows would be quick to take advantage of that fact. Thus they began a policy of appeasement, agreeing to various 'reasonable' demands from New York's neighbors in the hopes of satiating their desires. In the words of General Benjamin Wood, who would become the effective governor, "Bargains must be made to prevent bloodshed."

This meant that the militia agreed to negotiate claims with New England, despite lacking any official authority. However, the treaty would be used on multiple occasions by the New English Commission whenever more legitimate governments of New York would attempt to revert claim cessions. These cessions include the end to claims east of Lake Champlain, agreement to New Haven Province's claims up to the Hudson River, and the transferance of Yorkish Maine to New English control.

What was not agreed upon, and but what the Commission summarily issued as fact, was that Yorkish land north of the New Haven Border was open to New English colonization. Upon the reformation of the New York government in 1689, the royal governor and his advisory council (refered to in this period as the Commandery, as it was comprised of Wood and his men) refuted such claims and began actively attempting to settle their northern frontier, despite being at a great disadvantage in population. Further troubling their efforts were Maryland and New Jersey, who, having heard of the New English attempts to claim New York's hinterland, agreed to jointly lay claim to Yorkish territory west of the Delware River, with the general agreement that the land between it and the Suskehanna River would go to New Jersey, and land west of the Suskehanna would go to Maryland, who had already absorbed much of New Jersey's western claims in exchange for fishing rights heavily in favor of New Jersey, whose government focused itself not necessarily on territorial expansion as economic expansion, believing that control of both the Delaware and the North Branch of the Suskehanna would be enough to cement their trade power in the colonies. Both Maryland and New Jersey were cautious to claim only south of the far more audacious New English claims, in the hope that with the Yorkish government's focus on its north, their own claims would eventually be recognized."

"Given the destruction of the City of New York, and given the ensuing collapse of law and order within the Province of New York, that was then restored by forces of the New English Militia, the Maryland Volunteer Militia, and the New Jersey Militia, it was no surprise that Yorkish territorial sovereignty would begin to fall apart as well. The Treaty of Concord had not just New English and native delegates, but those of New York as well, namely members of the militia that had become the effective government after the majority of its public officials perished in fire. These men recognized that their colony would be in dire straits, and that their fellows would be quick to take advantage of that fact. Thus they began a policy of appeasement, agreeing to various 'reasonable' demands from New York's neighbors in the hopes of satiating their desires. In the words of General Benjamin Wood, who would become the effective governor, "Bargains must be made to prevent bloodshed."

This meant that the militia agreed to negotiate claims with New England, despite lacking any official authority. However, the treaty would be used on multiple occasions by the New English Commission whenever more legitimate governments of New York would attempt to revert claim cessions. These cessions include the end to claims east of Lake Champlain, agreement to New Haven Province's claims up to the Hudson River, and the transferance of Yorkish Maine to New English control.

What was not agreed upon, and but what the Commission summarily issued as fact, was that Yorkish land north of the New Haven Border was open to New English colonization. Upon the reformation of the New York government in 1689, the royal governor and his advisory council (refered to in this period as the Commandery, as it was comprised of Wood and his men) refuted such claims and began actively attempting to settle their northern frontier, despite being at a great disadvantage in population. Further troubling their efforts were Maryland and New Jersey, who, having heard of the New English attempts to claim New York's hinterland, agreed to jointly lay claim to Yorkish territory west of the Delware River, with the general agreement that the land between it and the Suskehanna River would go to New Jersey, and land west of the Suskehanna would go to Maryland, who had already absorbed much of New Jersey's western claims in exchange for fishing rights heavily in favor of New Jersey, whose government focused itself not necessarily on territorial expansion as economic expansion, believing that control of both the Delaware and the North Branch of the Suskehanna would be enough to cement their trade power in the colonies. Both Maryland and New Jersey were cautious to claim only south of the far more audacious New English claims, in the hope that with the Yorkish government's focus on its north, their own claims would eventually be recognized."

- The City by Thomas Hastings.

--|--

Decided to add some flavor to this map-based update on territorial claims. As before, the northern border with the French is nowhere near that clean in actuality, but coating the whole thing in various stripes whose end is muddy at best was not something I felt like doing. A more determined French border will occur eventually anyways, so it would also feel like a bit of a waste of time trying to get this one so accurate.

Last edited:

Part #7: The Bloody Year, Section #1: Offender of the Faith

Part #7: The Bloody Year

Section #1: Offender of the Faith

“Let those who stand against my People know Fear. For I am their sovereign king, the will of this Nation and the architect of its Common Good, and for my People I will do whatever need be done without hesitation. For I am born in a rank which recognizes no superior but God, and thus free to sacrifice my soul for this land.”[1]

- King Richard IV & I

--|--

“If one were to merely look upon a timeline of historical events in the British Isles, then the Bloody Year would appear to be a very sudden and confusing tragedy. However, to those who understand the history of the event, the true blessing is that it remained contained within the confines of a single year, and did not begin a lengthy war as the last conflict to ravish England’s shores did. Of course, while the incidents within were brief, no one can deny their impact, as the year of 1687 both created new issues and solved ones that were years in the making.

Let us then examine events prior to this, to better comprehend the setting in which conflict erupted. In the early 1670s, the Test Act was passed, which required that anyone filling any office, civil or military, had to not only make an Oath of Supremacy to the King of England as the supreme governor of the Church of England (although several Catholic officials were allowed to go without the oath under Charles II) but also were required to make a declaration against transubstantiation and receive the sacrament within three months of taking office. James, Duke of York, brother of Charles II, refused to make the declaration, and was thus revealed as a Catholic. This resulted in a great deal of panic amongst certain members of Parliament who realized that, with Charles II then without heir, the next monarch of England would be a Catholic. [2]

Some even reported belief in a conspiracy to murder the king by the Catholics, despite the fact that such a conspiracy would only result in Catholics facing greater persecution for murdering a king, regardless of if James sat upon the throne, and would also create the precedent by which James himself could be murdered in favor of his Protestant daughter Mary, who was wed to William III of Orange.[3] Luckily, these more deranged theorists were unable to gain much traction, and most of England’s populace, while greatly against Catholics, were not of a mind as to upset royal succession by supporting the so called Exclusion Bill, which sought to ‘exclude’ James in the line of succession to prevent a Catholic monarch. The bill thankfully failed, and upon a subsequent elections of Parliament, general concerns over the exaggerated amount and power of ‘Puritan’ criminals due to feeling New English colonists (a region then in the midst of the First Metacom War), as well as outbreaks of fever and flu that accompanied them, and other factors saw a Parliament less and less concerned with voting for the bill whenever it was reintroduced.

Recognizing, however, another solution, the backers of the Exclusion Bill proposed that Charles II’s recognized bastard son James Scott, Duke of Monmouth, popularly known as James Crofts, could be legitimized and made heir, Monmouth being both Protestant and a charismatic individual that had developed a strong influence of his own. It would be their fervent support of him, alongside their opposition’s strong disgust and loathing for actions against the Royal Family such as the Exclusion Bill, that would earn the common names of ‘Croft’ and ‘Abhor’ for the two predominant groups in Parliament for years to come.

What truly killed the bill, however, the aforementioned ‘other factors’, was the announcement of Queen Catherine’s pregnancy in 1680. While there was fear that it would result in another child that would not survive infancy, the hope was enough to sway many politicians that were less radical in their beliefs into at least abstaining until it could be determined if the child would be a viable heir. Some took this as opportunity to abandon the proponents of the bill entirely and vote against it as both unnecessary and disrespectful, while others merely chose to abstain their vote until such a time that the child either survived infancy, or did not, at which point they believed the bill could be reintroduced. Soon enough, Prince Richard was born, and, though sickly for much of his youth, would survive infancy, dashing any hopes of the Exclusion Bill and the precedent of Parliamentary power it would create, but generally all sides gave a sigh of relief that succession was secured. But, when Charles II briefly suffered illness, the Exclusion Bill supporters then realized they had a new problem; if Charles II died, no doubt James would become regent, and even acting as a second father to Richard. That the new heir might be corrupted into a Catholic sent them into a panic.[4]

Thus, they introduced plans to have Monmouth be made regent rather than James (once again cementing Croft as the name for the Opposition), upon the basis that the young Richard would need a Protestant upbringing if he indeed required a regency. This new proposal indeed gained a good deal of support, though never enough to become law. However, with Cromwellian allusions having already been mounting even before Richard’s birth, it was easy for Abhors to twist the idea that Monmouth, a recognized bastard and thus pretender, would have full access the young heir, could then kill the child and claim the throne himself. In response, wilder and wilder stories of James’ supposedly radical Catholicism began to circulate, some claiming he would have the boy tortured to forcibly convert as if he were an Inquisitor of Spain.

To add on to the conflict was a growing third faction of Crofts and Abhors that wished to offer compromise in the invitation of Mary as regent if it were needed, thus not requiring Monmouth be given power, while also ensuring that a Protestant helped the boy guide the realm. However, this group remained fairly small, as general extremization of both main factions saw them ignore possible alternatives, general unease with the Dutch with the Franco-Dutch War still in memory, and Mary had found herself ill relations with her father, as the two had quarreled via correspondence over the situation in England on matters of possible regency. In his letters, James, when prompted by his daughter, wrote that would certainly hope to advocate to Richard, as regent as mere advisor, for religious tolerance and a general weariness towards more radical elements in Parliament. Mary believed that some of James’ were too extreme, and she herself stated that she believed he ought to decline a regency in favor of regency council of himself, Monmouth, a few other other well-liked Protestant lords, and Queen Catherine, who had as of then recently gained a boost in popularity when Abhors circulated her remark that, “[her son was] to be King of England, and head of its Church. He must of course be a member of that Church.” James, however, was against the move, for reasons of a general distaste and distrust for most of whom she mentioned, barring the Queen-consort, and, but of course, a joint regency of himself and her would only make the situation worse. Thus rebuffed, Mary accused her father of lusting for power.[5] While some might assume this would make her all the more eager to agree to replace James as regent when asked, her pride instead made her refuse such offers on the grounds of her refusal to be ‘a pawn in [her] father and cousin’s game’. This route seemingly neutralized, the Marian faction remained but a vocal minority that often sided with the Crofts on most other issues.

And while Abhors remained the majority in Parliament, the population of England found itself increasingly divided, though many did not realize it, as, though each man knew what side of the argument he was on, most firmly believed that their then healthy king--having recovered to full health and famously offering a scolding speech to Parliament for ‘speaking of [him] as though [he] were buried,”--would live long enough to see his son reach his majority, and that the debates were merely hypothetical discussions that showcased general political beliefs, be that anti-Catholic or pro-Monarch. That was, of course, until the winter of 1686, when Charles II would be struck with illness once again. And despite all prayers, at the dawn of 1687, he drew his final breath…”

- History of the British Isles by Arthur Conchobhair, Viscount of Limerick

“[The royal bedroom of Charles II. Snow drifts outside of the window, and the lighting is dim. CHARLES lies pale and sickly, with ragged breath. Around him are CATHERINE, JAMES, RICHARD, and several LORDS. CATHERINE holds RICHARD as he sobs.]

CHARLES: D-do not cry, boy. [cough] You will be a king. And king [cough] kings [cough] kings do not cry. Listen to me, listen to us. We are your father, and we are dying, but we do not cry or moan or beg for life to God. We are the king. And know that we...I...will miss you. Will mourn never seeing you grow while within this mortal coil. But our strength is your strength. And your strength with be your son’s, and his son’s after him, and onwards to the End Times. And that strength too...is that of the nation. A kingdom must have a king, for without it is but a leaderless mob, unable, despite its attempts, to guide itself to anywhere but chaos. You are needed, boy, just we were when our father was killed. Do you… do you understand?

RICHARD: [sniffle] I….we understand.

[CHARLES gives a weak laugh, before breaking into a fit of coughing and CATHERINE’s grip on his hand grows tighter]

CHARLES: J-james!

JAMES: [Leaning in] I am here, my brother.

CHARLES: Guide him James. Help him become a man. You!

[CHARLES points at the LORDS]

CHARLES: Stand witness! Hear in your ear this, as if it were gospel of our Lord: We, Charles II, we...we name James, Duke of...Duke of [cough] We name James as regent for Richard, Prince of Wales! Regent, until he reaches majority. This we decree, despite belief by many that another ought take his place, for we find him best suited to guide this kingdom down a righteous and true path...

[Most of the LORDS nod solemnly, and several begin to write down the decree, verbatim. Focus on a few of them, who look to one another. A cut to the paper, and upon it is written ‘Duke of’. Slowly, they write in ‘Monmouth’. Dramatic tune rises.]”

- Excerpt, Regency (2017)[6]

“Charles II had been dead for only a few hours when the first parts of the Bloody Year started to turn. Despite several lords all bearing witness to his naming of a regent for his son, some of them had written down that James, Duke of York, was regent. But the others had written James, Duke of Monmouth. Which, given that, before Richard was born, one was the king’s Catholic brother Parliament had been fighting to exclude from succession, and the other was the king’s Protestant bastard son Parliament had been fighting to make heir, is a bit of a problem. Now, officially, James the Bastard, as most Abhor historians referred to him, was James Scott, Duke of Monmouth, but given the generally extemporaneous nature of the decree, that wasn’t solid enough evidence to disprove that the king had named him regent over his brother. Especially since made a point to mention that, whoever he had picked, was someone that plenty of people were going to disagree with, but that that person was best to guide England ‘down a righteous and true path’. What the hell does that mean? Nobody knew. Yes, Sarah.”

“But weren’t there other people there to confirm who he meant? Like his brother.”

“Yes, but if you were an anti-Catholic Croft, ‘righteous and true path’ obviously meant the one that wasn’t Catholic. But then, if you were royalist Abhor, ‘righteous and true path’ obviously meant one that wasn’t led by those backstabbing and dastardly Crofts. You are also right, though, that James, as well as the Queen, both stated that Charles had meant his brother. But then, both being Catholics, and one being the guy who would be named, meant most Crofts didn’t want to trust their testimony. But can anyone tell me who had the most support? Gregory?”

“Duke of York.”

“Yes! So, the word is sent that Charles is dead and to be buried some days afterward. After the funeral, James, Duke of York, is named regent officially, but during that process, several people contest it, and present the testimonies that James, Duke of Monmouth was the to be regent. They storm out, and then, just a few weeks later, time they took gathering their men, we get the March on London. A huge gathering of people, some lords, some from the House of Commons, some just commoners who joined up, and a sizeable number of soldiers and and former soldiers, all march through London, demanding that Monmouth be named regent. By all accounts, at least the ones we can prove as being without too much bias, the March was supposed to be peaceful, a major demonstration that they assumed would make James, Duke of York, and I’m going to keep saying it like that so you people remember which is which, concede to them. Their ringleader was the Earl of Shaftesbury, who entered a heated discussion with James outside of Parliament, and eventually James told him and his people to disperse, or be treated as disturbing the peace and face accusations of treason. Now from there things get...muddy. A lot of people say that the group refused to leave, and James angrily gave the order for troops to fire on them, or at least to startle them, and that’s when someone from the march fired back. But then most others say he only threatened the order before some shot from the mob. And then others still say that before he gave any order, a shot rang out. But regardless, someone had fired a gun, and it clipped James, Duke of York, in the ear. Seeing the regent gripping his bloody head and fall to ground was all the needed for chaos to break out.

“The marchers retreated, Shaftesbury and many others with them, fleeing for their lives from vengeful city-dwellers and from the actual military forces. But once they were free from London, they started telling their account of what happened, and very quickly tensions start rising. Now we may be thinking, what was James, Duke of Monmouth, doing during this? Well, he happened to be in London for the funeral, and hadn’t left yet when the march happened. He gave his statement that he was ‘readily willing’ to assume the regency when Shaftesbury and the crowd asked him, but when the fighting broke, he did not flee with them. Instead, he was put under arrest, and raged and moaned that James, Duke of York, was going against the obvious will of both the Lords and Commoners of England. At least until the first Battle of London…”

- Prof. Ernest Valdez, Lecture at the University of New Rubicon

“The first actual battle, if it can be called a such, to be fought in the Bloody Year, if not including the March on London, was the First Battle of London in late February of 1687. The battle was a swift event that lasted only a day, and was less of a grand fight as it was a sudden takeover. Since the March, there had been riots across the city of London as Protestant citizens were torn between loyalties to faith and loyalties to state. There were also numerous members of the criminal element that used the unrest as a means of furthering their own ends. With this chaos growing, the Duke of York was already preparing to flee the city with Prince Richard and find safehaven elsewhere, planning to let things calm down before using the military to round up ringleaders and remove them as a threat. However, in the meanwhile, as word spread of the Duke of York’s regency being contested by the supporters of the Duke of Monmouth, and of the casualties of the march, an army gathered. Beginning as a rally immediately after the march, several defecting officers of the army and members of Parliament began to rile up peasants in the countryside, and soon enough had a formidably large, if untrained, force. Notably, the Earl of Shaftesbury and several other lords that had effectively become the founders of the Croft movement, chose not to lead any form of open rebellion, calling for the group to simply protest rather than fights. When their cries went ignored, they instead invested their resources in attempting to sway more of the nation in their favor peacefully, so that York would be forced to concede, rather than face a rebellion of all of England.

But despite such efforts to prevent furthered conflict, there came upon the city of London, en masse, the army, led by a number of disgruntled officers, as well as Joseph Pride, soldier in the New Model Army and son of parliamentarian commander Thomas Pride, who was almost hanged in place of his father’s corpse. There was also Charles Lambert, who claimed to be the bastard son of Charles Hatton, son of the Christopher, 1st Baron Hatton, and Frances Lambert, daughter of Major-General John Lambert, although the validity of such a claim was never confirmed and greatly denied by the Hatton family.[7] Upon seeing the Monmouthite force approaching, there was an initial attempt by the Duke-regent to defend the city, only for members of its garrison to turn on him. Realizing quickly that many of his forces were traitors, he began an immediate escape, with loyalist forces protecting his flight with the heir. Many historians have ruled the decision overly-cautious, as the number of loyal, well-trained troops could have held London if they had not been covering a retreat, most of the dissention in the ranks being quickly crushed. Thus, while James, the Queen-consort, and Prince Richard had escaped, ultimately it was a blow against their cause, as London was effectively in control of the Protestant forces, despite numerous riots (now against the Monmouthites).

As a counter to this victory for the Protestants, however, Monmouth himself was supposedly appalled to see an outright war being raged in his name. While the rebels themselves claimed he did so under threat of death, Monmouth officially denounced the movement and claimed that their inability to sway the nation meant they must surrender peacefully, admittedly doing so while still in the custody of the Duke of York, but he did not revert his statement upon being freed by defectors some days later, instead taking refuge within loyalist controlled England. His own personal records, and those of his family, have been unclear as to the truth, but most analysts of the period believe that it was a calculated move on Monmouth’s part, for if there was a Jacobite[8] victory, he was to seem innocent, but if the Protestant’s were victorious, he could ‘reveal’ that his condemnation had been coerced, and could thus find himself victory in either case. His actions may very well have doomed his own ambitions, however, greatly hindering the legitimacy of the Monmouthite cause as they were forced to run a Parliamentarian government, creating association with the likes of Cromwell. Many believe then that he simply foresaw a victory for the Duke of York and chose to ensure his own safety…

...Parliament itself was greatly divided, but nearly two-thirds of its membership chose to support the Duke of York, though these men were forced out of London by the so-called ‘Small Parliament’, which declared those not in favor of the Protestant forces to be traitors to the nation. Meeting in York itself, the Jacobite Parliament ironically contained a number of Crofts in its membership, men who, like Shaftesbury, had wanted a peaceful revolution, or felt that Monmouth’s refusal to agree to rebellion meant that its members were little better than a band of resurgent Roundheads. There were also the Marian Crofts, whose role would come later, and a collection of true loyalists who did not wish to see the Abhors use circumstances as a means of empowering the monarchy or restricting civil liberties in the aftermath. Many of these individuals were not ‘Crofts’, in the sense of supporting the Duke of Monmouth politically, before the outbreak of conflict, but were instead branded as Crofts, in the sense of being proponents of minicratic[9] royalism and Protestant prioritization, retroactively as they joined that political faction following the war and advocated against Abhorrist power grabs during. Chief among these individuals was George Villiers, 2nd Duke of Buckingham, who returned out of retirement following the First Battle of London, and though was not officially a member of the Jacobite Parliament during 1687, he spoke on numerous occasions and was even (perhaps accidentally) counted as a voting member. Buckingham was once a loathed and humiliated figure, but his rational proposals and lack of fear to speak up against the dominating Abhors quickly cemented him in a leadership role for his group--especially given his publicly known taste for both Monmouth and Shaftesbury--and for all Crofts in general as he berated any Abhor who attempted to paint disagreement as treason. It would be his famed quote that would come to define the Crofts after the war: “It is not treason to propose a better idea.”

The Duke of Monmouth himself would eventually take a seat in the Jacobite Parliament, although not until mid-August, when loyalist victory was evident to all but the most fanatical of rebel leadership, and with this act numerous members of the Small Parliament fled London to gain some measure of mercy. The Earl of Shaftesbury would not sit in either Parliament until October, when the Small Parliament had been dissolved entirely and its remaining members arrested...

...Most ensuing skirmishes following the seizure of London were minor, often unmarked in the annals of history. But with the beginning of Scottish involvement, the would be rebellion truly came into fruition. Seizing Glasgow, the Scottish rebels were a mixture of forces, led by Richard and Michael Cameron, Covenanters that had been on the run from Charles II’s government for some time. Within their forces, however, some truly supported Monmouth, others merely despised the Catholic York, and others still fought for a more autonomous or even independent Scotland, utilizing the opportunity to gain the favor of the Small Parliament if they assured Monmouthite victory. Thus, with the Scottish rebels and a growing number of defectors, the Protestants now had the ability to rival the Jacobites in only a few months. But despite this, the leadership did not find itself satisfied, and Joseph Pride eventually began to champion that the ‘Glorious Anti-Papist Revolution’ be ‘spread near and wide like a flame in a field.’ Essentially, he and others in the Small Parliament desired the entire nation to immediately agree with them, not a drawn out series of battles that would slowly hack away at loyalist regions. From both London and Glasgow, the rebellion attempted to spread, sending out their men to aid smaller, fledgeling rebellions and to help organize entirely new ones. In some ways, the succeeded, with strong militias securing much of the Bristol Channel coast and several cities in southern England with minimal bloodshed. In many other cases, however, they failed. In Devon and Cornwall, for instance, while the former would see a successful uprising against garrisoned troops, their attempts to spread their control to the rest of the peninsula saw their defeat, reinforcements from London unable to arrive in time, and similar results occurred at Inverness.

Perhaps their most damning failure was that of the Army of Carlisle. Successfully repulsing a loyalist attack, the rebels in Carlisle were immediately ordered by nervous Richard Cameron to march North to help defeat a gathering of loyalists, despite a lack of supplies and general weariness. Regardless, a combined assault from both Carlisle and Glasgow would be numerically advantaged, and expected to see a victory that would effectively solidify control over Scotland for the Monmouthites. The Battle of Galloway instead ended in a resounding victory for the loyalists, due in large part to superiority in both tactics and morale. This loyalist militia was led by Thomas Fairfax, 5th Lord Fairfax of Cameron, who, a member of the pre-war Yorkshite militia, had been hunting with several friends in Scotland when the rebellion began, having until then been fortified in the Montgomerieston Citadel in Ayr, and taking a leading role in organizing loyalist Scots and members of the military. After Covenanters lines broke, the Army of Glasgow, led by former officers, was able to successfully retreat and fortify their own city, but the Army of Carlisle, mostly of peasant stock, dissolved in a frenzy. As the loyalists marched towards Carlisle, they found it unprotected and easily occupied, and as word of this spread, faith in the rebellion suffered greatly. When the rebels regrouped in the South, Fairfax drove on and was able to trap them at Lancaster, a fairly neutral location. The rebel actions of seizing food and weapons from the local citizens as Fairfax set up a perimeter around the city meant that the remnants of the army were soon enough pushed out of Lancaster by its populace, right in Fairfax’s jaws. Glasgow was soon enough an island in a sea of enemies. However, despite these failures, most in England itself could still remember at least tales of the last Civil War, if not the war itself, and thus many were content to allow the two sides to clash while merely awaiting for a victor to emerge, resulting in a quick loss in recruitment numbers for the rebels after an initial surge. In contrast, more and more men were willing to throw themselves behind the Jacobites in hopes of profiting from what was an ever seemingly assured victory…

...In Wales, the while the southern coast had fallen into Monmouthite hands, transference of this control northward failed, largely in part to the quick thinking of William Herbert, 1st Earl of Powis, who raised an army in defense of the Duke-regent as soon as he had heard of the First battle of London. His zealotry in persecuting and vanquishing the Monmouthites was well justified, having been greatly persecuted by their numbers, being one of the leading Roman Catholics in England, even accused of conspiring to kill the King, an accusation for which he was temporarily arrested for before being released not long after, only to hear that there had been an attempted murder of his wife.[10] Powis was thus given a perfect opportunity for a quest of both vengeance and patriotism. Initially, he and his army marched East in hopes of reclaiming the capital, but he was then informed of the large amount of southern Wales that had risen up in favor of the Protestant rebels. Turning his army back, Powis would engage a numerically superior force at Vyrnwy Valley, and successfully utilized his cavalry to trap the entirely infantry rebel army between his forces, barring them from either entry point. For some months afterwards, Powis’ army, realizing that much of the loyalists forces were focused on Scotland and southern England, attempted to contain the Welsh rebels in the South. The arrival of several loyalists militias, including Fairfax, who had recently received the news of Richard Cameron’s death by infection, and ensuing power struggle in the Covenanters had resulted in an easy conquest of Glasgow by loyalist forces. Together, the two would crush the last of the major Monmouthite holdouts in Wales, most decisively and famously in the Battle of Afon Nyfer.

...By all accounts of the time, the Protestant’s had the clear pull over the average Englishman, at least initially. One of the greatest moves for their legitimacy was their capture of Prince Richard and Queen-consort Catherine in late March, who were being transferred to Alnwick Castle, an large but uninhabited location that would ensure the prince’s safety as few but his guards and the Duke of York would know where he was. Having crossed into Northumberland, one of their escorts betrayed them, resulting in the young prince being held in Scotland before he was sent south to London in early May. This, combined with control of London, resulted in a large recruitment to the Protestant army. However, with the collapse of both the South-Western rebels and the majority of the Scottish ones, and as the Duke of York managed to keep the two main strongholds of rebellion from connecting their zones of control, looting of farmland, collecting of ‘taxes’ by troops, and deserters turning into bandits began to rise in occurrence, greatly building resentment for the Monmouthites. Public opinion swayed further and further towards the loyalists, until the Duke of York was confident enough to begin preparing a proper reclamation of London, gathering his forces in Worcester. This force was then used to decimate the rebels in Gloucester, including Charles Lambert, who drawn and quartered after spitting in the Duke-regent’s face and calling him a ‘putrid papist.’

This battle effectively left the Monmouthites only in London, with their Irish allies soon to be eliminated by the militia led by the aged Lord Burlington and Darragh Conchobhair. In a little over a month’s time, the Duke-regent’s army was preparing for their assault on London. Of course, it was at that moment that the Duke of York received a message that made him pale; his son-in-law was in Norfolk…”

- The Bloody Year, by Dr. Konstantin Ulyanov

“I remember it all very well. At the time I was in punishment for my seventh attempted escape, and thus far my most successful. Thus I was in the tower, but was reasonably accommodated. The sound of battle had only just stirred me when the Scotch thugs had burst in, barricading themselves like idiots. What sort of fools attempt to protect themselves by hiding in a prison-tower? But I digress. They grabbed me, beat me when I began demanding to know what was going on. While I had received ungentlemanly treatment by such fiends before, during my kidnapping and more minorly during my stay in Glasgow, these men were no longer under any such orders to treat me respectfully. They’re last hope, if the battle went as most expected, was to ransom me and pray that, in exchange for my safety, they would earn an oath from my uncle to let them live. That I was covered in bruises was not something they truly cared about...

...From what I could hear and what they said to one another, the loyal soldiers under my uncle were able to quickly punch through the rebel defenses, and had since used the rioting of the commoners to seize much of the city within the first day. By the second day, my captors were forced to fight off others who had a similar idea as them, and I watched as they butchered their once comrades with little hesitation. It was not long after that, when I foolishly made a remark, that one of them cut my cheek. Some say it has become a signature for me, a way by which all know me, and that it adds to my appearance. I suppose I ought to thank the man, and perhaps I would if he were alive…

...On that fourth day, the remaining rebels fled the city, and their false Parliament was captured. Just as they had planned, the Scotch attempted to use me as a hostage in exchange for their safety. And my uncle agreed, promising them that ‘he would give no order for them to come to harm.’ As soon as we had exited the tower, and I was given to him, however, Lord Powis had the men cut down. I still remember his stoic look when my uncle shouted at him, spoke of honor and oathes. Powis had simply responded that he had made no such oath, and that my uncle’s words had been that he would give no order to have the men killed, and indeed that had not happened. Instead, he acted without an order to do what he felt was right, especially upon seeing me, bloodied and bruised…

...Only a few hours of celebration, of joy, of being held by my mother again. And then it was fear once more. The city was pacified with force, the fortifications, luckily spared much damaged, were readied to repel another assault. My cousin was on his way...”

- Personal memoir of King Richard IV & I

--|--

[1] This last sentence (of the first part of it) is a quote from Richard I, who said it to the Holy Roman Emperor after he was accused of crimes committed during the Crusade

[2] This is all from OTL

[3] In OTL, thanks to Titus Oates and company, this spun out of control into the Popish Plot. Since he’s dead TTL, the occasional conspiracy gets popular, but nowhere near to the degree as his did.

[4] This has all been established already in previous posts.

[5] James was famously greedy in OTL.

[6] Being a film, the scene is inherently dramaticized, edited, and given a firm bias for the side supported by makers. In this case, it’s a biopic for James.

[7] This is based on a few references I’ve found to Lambert’s daughter marrying Charles Hatton secretly for a year before his father took away his money and the marriage eventually ended. TTL, this may or may not have happened, but likely Charles Lambert, if he even in Frances Lambert’s son, is not necessarily Hatton’s, merely looking to cause controversy to create a name for himself.

[8] If you couldn’t tell, Jacobite is a term for loyalist in TTL.

[9] In OTL terms this is essential liberalism

[10] In OTL he was arrested for the Popish Plot, and then his wife was nearly arrested for another Catholic conspiracy to kill the king that Oates popularized.

Last edited:

Part #7: The Bloody Year, Section #2: Blood Orange

Part #7: The Bloody Year

Section #2: Blood Orange

“Stadtholder[1] William III had advocated to his wife on multiple occasions that she accept calls by some members of the English Parliament for her to come and act as compromise for the question of whom would act as regent. A noble and pious ruler, but ultimately shrewd and wise, he both viewed the papist regency of James to be dangerous, and recognized that the growing forces against the Duke could result in a destabilization of England.[2] Furthermore, if King Richard IV were guided by William’s wife Mary, cooperation between the Dutch and the English was almost guaranteed, thus not merely eliminating one of his nation’s enemies, but making them into an ally. However, despite attempts by some individuals to tar the Prince as such, William III was not the kind of individual who would invade England without cause, despite the political opportunity...

...If individuals must be blamed for the events of the Winter of 1687, it ought to be George Savile, 1st Marquess of Halifax; William Cavendish, 4th Earl of Devonshire; and Henry Sydney 5th Earl of Leicester.[3] Savile was politician of some renown that had once been a favorite of King Charles II and even a friend of the Duke of York. However, his support for the Test Act, which outed the Duke as a Catholic, and his approval of persecution of Catholics earned him enemies, including the general disapproval of his king.[4] While he would be made a baron and marquess, he struggled to maintain his influence in court after the more moderate members of Parliament dominated with the birth of Prince Richard. Despite a strong aversion to Catholicism, however, Savile was not a proponent of Shaftesbury and other Monmouthites, and when rebellion broke he became a member of the Jacobite Parliament in York. Lord Cavendish was perhaps the best individual to be seen as a rival of Shaftesbury in terms of leadership of the Crofts, or simply the anti-Catholics as they were at the time. Cavendish would become a prominent member of the Jacobite Parliament, greatly injuring the strength of support for the Monmouthites in the nobility, as Shaftesbury had similarly refused to endorse the uprising, but Cavendish’s outright hostility to the Duke-regent made many disassociate themselves from him for fear of being accused of treason.[5] Lastly, Sydney was a keen manipulator, often viewed as a simpleton and sycophant. With the death of his brother in 1679 and his nephew in 1684, he would inherit his earlship, quickly embedding himself further in court intrigue.[6] And so we have trio; a betrayer, a failure, and a snake.

It would be they who formed a strong Marian faction in the Jacobite Parliament, calling for the Duke-regent to step down in favor of his daughter. Alongside four other lesser lords, together known by the English as the Damnable Seven, they would become infamous for maintaining correspondence with William III and keeping him apprised of the situation in England. These correspondences, however, were often incredibly hyperbolic, and stained by anti-Catholic rhetoric, rendering William and Mary’s view of the situation as being bleak and utterly chaotic.[7] The final letter sent from Cavendish spoke of a terrible Monmouthite offensive, but that word had come that the Duke-regent would be striking at London, in vain by Cavendish’s view, and he lamented excessively about word from spies of Prince Richard suffering ill-treatment in rebel hands. Their letters stopped from that moment, as the Jacobite Parliament began plans to relocate back to London, as Abhors, increasingly led by Charles Talbot, 12th Earl of Shrewsbury,[8] eagerly argued for them to move while the Duke-regent engaged the rebels so that they might arrive as the battle ended. Thus, preparing to journey to London, Parliament would receive news from Well-next-the-Sea of a Dutch ‘invasion’, and most would quickly flee back to York while some would hurry ahead to London proper.

For, having read the last letter, Mary’s heart broke for her nation, no matter how misinformed that heart may have been, and agreed that William should go forth with invasion. Both readily agreed that England both wanted and needed a Protestant at its helm until Richard was of age, but not only was Monmouth against his own rebellion, but its composition had showed itself as being power-hungry brutes and little else. Having been ready to act in mercy for some time, William launched his fleet, being a bold leader who preferred to lead his men on campaigns. Arriving in England, the locals of Wells-next-the-sea believed it to be a foreign army of conquest, and the battle that ensued most certainly hindered William’s plans to quickly take England with minimal bloodshed, the losses to his army meant that intimidation through sheer size would no longer work.

But the Stadtholder was clever,[9] and had a second army already landing far north, an army which was to reinforce the Monmouthites in Scotland before usurping them to control the region, the hope being to use Scotland as safehaven and a source of troops. When it was discovered that the rebels had already been crushed and pushed to the hinterland, the army turned south, and would have been successful in reinforcing William’s main army had it not been for Richard Lumley. The then Viscount had raised his own force, the famed Lumley’s Regiment of Horse[10], and was crushing remnants of rebels in Northumberland when he heard of the invasion in both the south and the north, gathering up smaller forces of English militia and army, he would decimate the Dutch forces coming to aid their leader, having caught them by surprise not far from Newcastle-upon-Tyne, the battle moving and greatly damaging the city.

William would not hear of the loss until it was far too late. In the meantime, he had used his still large force to begin securing south-eastern England. While half his force pressed West, he personally led them South, trouncing an English force in Dedham Vale, and his men being victorious in the Battle of Rutland. These victories, however, would ultimately mark the greatest extent of William’s control westward, as sad as that is. Regrouping his force, in early December he rode for London, despite the cold, hoping to catch the Duke of York off-guard. Furthermore, at the time, due to Dedham Vale, William’s army was easily double that of the Duke-regent’s forces in London, and the prince hoped to at least reach the city and make camp, intimidating James into surrendering. This likely would have worked, if it weren’t for the Irish…”

- William III: A Study, by Georg van Amsberg

“To say the role of Ireland in the Bloody Year is ironic would be a gross understatement. Initially, when word of Charles II death reached the isle, alongside the possibility of a dispute over who would be regent for Prince Richard, Irish Catholics across the counties began to sharpen their weapons in preparation for a revolt. In truth, research has found a number of sources that report more than one meeting of Irish men in preparation for an uprising, and a number of ‘loyalist militias’ began as rebellions.[11] However, events would see them on a very different side of history. When the March on London transitioned to the First Battle of London, Monmouthites in Ireland acted swiftly. Seizing the northern region of Ulster, they declared Ireland for the Duke of Monmouth, hoping their actions would see them rewarded, and see a return of greater Catholic persecution. Several Irish peers who had actually been in Ireland at the time were quickly in uproar. Notably amongst them was Richard Boyle, 1st Earl of Burlington and 2nd Earl of Cork, who had fallen ill while visiting Cork, and was still ill at the time of the battle. The Irish Parliament, however, when called, was visited by Lord Burlington who mustered enough strength to berate the Monmouthites and call them traitors, leading a walk out of Irish MPs who would soon form the Irish Jacobite Parliament in Cork...

...Burlington, recovering, soon began to organize an Irish militia, which was surprisingly easy as word spread across Ireland that extreme Protestants wanted to supplant the Catholic James as regent. Many Irishmen saw a self-interest in preventing this, others saw a political opportunity, and some merely wanted an excuse to kill northern Protestants. As mentioned, several rebellions cropped up across various regions. Two notable examples can be found. The first was in Connaught, where an Irish rebellion, its leaders fully intending to create an independent and native-ruled Kingdom of Ireland, gained a pyrrhic victory against the Monmouthites at the Battle of Gowlan River. One of these leaders, namely the only one to survive and also thankfully the most moderate, was Darragh Conchobhair, a man originally from Limerick who had gone North to care for his ailing sister. Conchobhair would eventually meet Lord Burlington, and he would agree to organize his men and other Irishmen that were ‘firmly against the northern traitors’ to fight officially for the loyalist cause.[12] The other notable example of rebellion, was when a sizeable army of men was utterly defeated by Protestant forces in the Battle of Louth, seeing Dublin and much of the eastern coast fall under Protestant control, if tenuously. The Monmouthites certainly not looking to truly control the entire island, of course. They merely hoped to hold it until the Protestants in England succeeded and reinforced them. Thus it was only a matter of time before they withered away in number…

...With the South either loyalists or simply anti-Protestant, Lord Burlington’s army was able to grow and become large enough to win most skirmishes in found itself in, regardless of the lack of discipline in its conscripts. When he reached out the Conchobhair, the two were able to then begin to properly motivate and divide the army into effective forces, trusted Irish members of Conchobhair’s army commanding many Catholic peasants who remained insubordinate to Burlington[13]. Now ready, they would eventually take control of Derry in the Summer, in a battle that would leave much of the northern regions easily conquerable. The only true nut left to crack was Belfast, which the Irish Protestants leadership had holed themselves in for the time being. Burlington would hold off attack, instead attempting a slow war of attrition. That was until he heard that the Duke-regent was gathering his forces to retake London. Realizing that more equipment and men would be needed to get rid of the rest of the rebels, Burlington and Conchobhair turned their forces South, leaving just enough men to keep pressure on the Protestants should they attempt to reclaim their territories. The rest of the army would eventually see battle near Wicklow, winning against an impoverished Protestant force that had not seen supplies from England nor from the north in some time…

...As the Monmouthites retreated to Dublin, expecting Burlington to follow, the loyalists instead went to into Wexford and crossed the Irish Sea using a number of commandeered civilian vessels. From there was a straight forced march to London. Burlington and Conchobhair would arrive just a few days before the Dutch, and were almost attacked by loyalists in London. They were quickly welcomed, regardless of the army’s composition, and were informed of the incoming invaders. With these Irish forces, the defenders in London were no longer outnumbered, though their size was not great enough to ensure them a victory. But luckily, yet another militia of loyalists would arrive to save the day…”

- Baile Do Chách, by Aodhan O’Cearbhaill

“So what is special about the death of Charles II? What about it was different than a different king’s passing? Here is a clue: it’s what happened right after that I’m looking for. Yeah?”

“The Bloody Year?”

“Hey watch your mouth! I’m kidding, I’m kidding. Yes, the Bloody Year. Or as Caliguddus put it a little over a century later: The War for Who would be Somewhat-King for a Few Years. Now you read about the first half, and covered it extensively in lecture. For this recitation, we’re going to look at the back half, and at Virginia’s role. Now who died right after the king?”

“Governor Berkeley, after he was given the news.”

“Correct, the Governor died. So then Virginia needs a new governor, and the question arises of who it should be. Anyone know who ran things in the meantime? No? It was the guy who ran it before and after; Nathaniel Bacon. He and his friends ran the colony as they waited to hear about a new governor. However, their message was ignored as the war in England went on and on. That was about when Bacon heard about the war itself. And then he got an idea.

Some say he was always a loyalist, others that he was just going to see who was winning in England when he arrived. But regardless, he took a few months to have a small militia outfitted, a sort of honor guard, not intended to fight as much as to make it appear they were willing to fight.[14] These guys were some of the best soldiers and hunters in the colony, and when Carolina heard about Bacon’s expedition, they mobilized their own men to join him. Their troops were a lot more loyalist, and it may have been because he feared them turning on him that Bacon talked about his loyalism on the voyage to England.

So there they were, two small militias on a boat, with new guns and shiny new blue uniforms[15], and they land in England in late November. This was intentional. Bacon thought the winter would be when the armies would bunker down to wait until Spring, so he could present himself to the winning party and then rest and recuperate with them. But they hadn’t. The Duke of York wanted to secure London first, and then William III of the Dutch had decided he would fortify himself around London and starve them into surrendering[16]. But with the Irish reinforcements making the loyalist army a hell of a lot bigger, the Duke of York would end up gambling a battle rather than get trapped. When the fighting hit in early December, it was basically a fair fight, but with the advantage going to the Dutch. By the time Bacon arrived, being informed along the way about what was happening, the English army was about to break. But then in come the Virginians and Carolinians to save the day. Using their rifles, they began to pick off Dutch commanders and, in a very dramatic fashion, killed William III right as he was rallying a charge, shooting him off his horse. And when you see your leader getting his brains blown out mid-sentence, that tends to hurt your morale. What happened then?”

“The Dutch retreated, and got picked off by pursuing loyalists before they got to the coast and were allowed to sail home.”

“Yes, and?”

“And then after the battle, the Duke of York showed gratitude to Bacon by making him Baron Bacon, and creating the Barony of Jamestown. Then he made him Governor of Virginia.”

“Well done! And so we have General, Governor, and Lord Bacon. Does anyone know what else we call Bacon? Oh, Benjamin, you actually know this?”

“Delicious.”

- Recitation for HIST1088, University of Richmond

--|--

[1] William is more commonly referred to as Stadtholder TTL for reasons that will be seen latter.

[2] The author is Dutch, and as such has a far, far more sympathetic view of William than an Englishman would, who would typically characterize him as a greedy warmonger with his plotting shrew of a wife.

[3] These names ought to be familiar to anyone who has studied OTL’s Glorious Revolution

[4] Pretty much the same fate as OTL up until the divergence of Richard, as in OTL Savile was able to regain his influence

[5] Unlike OTL where he became a Whig leader following the ascension of William and Mary

[6] In OTL he was often written of by his fellows, but was a skilled manipulator

[7] This is due to both their own pessimism, desire to encourage Mary to agree, and to a lack of clear reports about actual goings-on in England.

[8] Who in TTL did not convert away from Catholicism to avoid persecution in the Popish Plot

[9] Again, the author is being overly-reverent, as a two-prong attack alongside the lending of support to possible allies isn’t too genius a strategy.

[10] Lumely did the same in OTL, and they later became the Queen Dowager’s Horse and later the The Carabiniers (6th Dragoon Guards) of the modern British forces

[11] This author is essentially willing to argue for what is an unpopular (but true) theory of TTL, as most history books would say the Irish rebels wanted to fight back against the Monmouthite extremists, and were more than happy to become official loyalists, rather than being true traitors themselves that joined out of necessity and a common foe.

[12] Something, something, enemy of my enemy is my friend.

[13] To be expected given he’s an Anglo-Irish Protestant lord and these Irish Catholic peasants are currently fighting Anglo-Irish Protestant lords.

[14] By this, the speaker means that Bacon hoped to present a small but effective force as a show of patriotism without actually committing much; just enough men to make it appear that he scraped together all the best he could find, but not enough to leave the frontier of Virginia defenseless or to actually risk too many men. Given European aversion to rifles in the present moment of TTL (and OTL), Bacon also expected correctly that having even a small group of sharpshooters would give a large advantage.

[15] Blue for no reason other than an excess of dye. By this point red uniforms were not at all universal in the British army, and if anything, given that red dye was so cheap, Bacon would want his men to look a bit less shabby by outfitting them in something that wasn’t red.

[16] Notice that some portray William as wanting to surround London to make camp and scare them into a surrender by Spring, others that he intended to starve them in a long Winter siege. Considering that the Duke of York feared both possibilities and ordered an attack, no one can know what would have happened.

Last edited:

Wish I could have gotten this up yesterday like I planned, but a series of events (namely a late wake-up, late buses, and a power outage) intervened. But here it is, Section #2! Section #3 will come either tomorrow or even later today, and will be covering the aftermath of the Bloody Year in England, the Netherlands, and the colonies.

The boarding school in Massachusetts? Best I can tell that was founded in late 18th Century, and we're still in the 17th, but I expect something like it to be around eventually if that is what you're talking about.

vive l'épuration

Is Milton Academy still around ITTL? If so, what is it called?

The boarding school in Massachusetts? Best I can tell that was founded in late 18th Century, and we're still in the 17th, but I expect something like it to be around eventually if that is what you're talking about.

Well that's not ominous...

vive l'épuration

Bulldoggus

Banned

Half day, half boarding. And yeah, 1799 it was founded.The boarding school in Massachusetts? Best I can tell that was founded in late 18th Century, and we're still in the 17th, but I expect something like it to be around eventually if that is what you're talking about.

Long live the *Google Translates* oh shit...vive l'épuration

Part #7: The Bloody Year, Section #3: Peace in the Meantime

Part #7: The Bloody Year

Section #3: Peace in the Meantime

“Men do well not to question law if they have no suitable replacement themselves.”

“Law exists only when it is followed or enforced. One requires the will of the general public, the other the will of the sovereign. And the public always proves stronger.”

“A king is a pawn is a man is a wretch. A queen is a player.”

“Come along, children, come along, stay close. I know they do things differently where you’re from, but in England you stay close and stay quiet. Now then, in this spot, on the first of January, 1688, the Duke-regent James, of the House of Stuart, did, with the approval of the boy-king Richard IV, declare the Loyalist Acts, a piece of legislation passed by the Jacobite Parliament that instituted several new peerages, enacted several attainders, ordered several executions and exiles, and awarded several honors and rewards to those who earned each. Hand down, boy, I am offering no opening for questions at the present. Now then, while I would go into detail each and every lord put to the axe for their treason and ascended for their loyalty, we have a schedule to keep, meaning I will expand upon the more academically pertinent facts of those whom had notable careers both during and after the Bloody Year.”

“May I use the critchah?”

“Hush, boy! You can use the lavvy when I am finished. Now where, was I? Oh yes, yes, pertinent figures who were affected by the implementation of the Loyalist Acts. There was Darragh Conchobhair, who was made Lord Conchobhair, Viscount of Limmerick,[3] who himself became Lord Chancellor of the Parliament of Ireland, being second in authority only to Lord Burlington, as he preferred to be styled, who was himself Richard Boyle, 1st Duke of Munster, 1st Earl of Burlington and 2nd Earl of Cork, who was appointed Viceroy of Ireland, to act effectively as regent for Richard IV in Ireland, much to the chagrin of the Duke of Ormonde, who was attained for standing with Monmouthites, though his loyalist cousin would be granted his title. Other titles created in the Irish peerage whose holders need not be necessarily known are the Marquess of Clanricarde, Earls of Kildare and of Desmond, and Viscounts of Derry, of Donegal, and of Meath, Barons of Wexford, of Kerry, of Louth, of Kilkenny, and of Galway, who I only mention as they radically changed the peerage of Ireland to contain a dominance of Catholics and/or Catholic-friendly Protestants, and native Irishmen. There was also the creation of the Knights of the Royal Oak, to whom various lords were inducted, including Lord Bacon of Jamestown, and all of his commanders in both the Virginian and Carolinian militias, and both colonies were officially renamed the ‘Cavalier Colony of’ in honor for the part in ensuring loyalist victory.[4]

In England, Charles Talbot, 12th Earl of Shrewsbury, would be made 1st Duke of Shrewsbury, and would himself become Lord Chancellor of the Parliament of England. It is worth noting that prior to 1687, the Lord Chancellor served as a member of a privy council and president of the court, as well as presiding officer for the House of Lords. After the last narrowly elected Speaker of the House of Commons, Henry Powle,[5] became a Monmouthite, the Lord Chancellor was thus made presiding officer for the Commons as well, and this applied to all three Parliaments. Shrewbury’s ascension would start a bitter rivalry with George Villiers, 2nd Duke of Buckingham, who was mockingly styled Mirror Chancellor of Parliament in that he and his own group of Crofts, who referred to themselves in partially joking fashion as His Majesty’s Most Loyal Dissenters, or simply the Dissention as we call them now, formed their own policies and alternative bills. Said term, mirror chancellor, and that of the Mirror Cabinet, remains a permanent fixture of politics to this day.[6] But perhaps one of the most significant rewards is that of a figure whose prominence in the Bloody Year is often understated or ignored, but whose skill and ability is found in his own titles, that being Robert Spencer, 2nd Earl of Sunderland, who maintained order in the Jacobite Parliament with his caustic tongue berating all sides, and who chose to hurry on to London at word of the Dutch Invasion.[7] He acted as an advisor to the Duke-regent, and as a tutor to Richard IV. Given his affirming vote to the attempted exclusion of the Duke prior to Richard’s birth, and his general dislike of the Duke, his reward in the Acts was initially one of a simple recognition of loyalty despite that, and that he remained a staunch royalist. However, very soon in 1688, he would time and time again continue his regulating position in shouting down both Lord Shrewsbury and Lord Buckingham, and this saw him leading most neutrals in court. This neutrality, his loyalty to the crown and country, and his lack of major scandal made him and ironically trusted individual by the Duke-regent, and the pair eventually became confidantes, often jokingly trading barbs. His influence grew until he was able to openly criticize the Lord Chancellors of England, Ireland, and Scotland, as well as the Mirror Chancellors of the former two, who hard arrived to discuss war with the Dutch. When King Richard IV reached maturity, he officialized the mocking title that this incident had earned him: Supreme Chancellor, making him head of the privy council, overseer of all Parliaments (primarily the English one, of course), and chief emissary of the crown as multi-national functions. As I am sure you boys know, this is still the title used by the head of government today.[8]

Now, you, may use the lavvy, and the rest of you a free to field questions, in an orderly fashion, until we move on to the next monument. Yes, you there.”

“You told us the Lord Chancellors of England and Ireland, but not of Scotland. And lots of Monmoo-, er, Mouthy, er, rebel people were in Scotland, so plenty of titles there had to change, right?”

“That is astute of you, boy. Indeed, this did change, and a Lord Chancellor was created there too. However, in general they were seen as lesser in influence than those in the Irish and English peerages, and they would soon be rendered even more so under the reign of King Richard before they, of course, ceased to exist.[9] Now, you.”

“What about Monmouth and Shaftesbury? Didn’t they start the whole bloody thing?”

“Watch that tongue, boy. But, yes. I was going to save their fates for later, given their descendants roles in history, but I suppose I can elaborate now and reiterate later. Now, Anthony Ashley Cooper, Earl of Shaftesbury, was recognized by the Duke-regent as a fount of the troubles that had ravaged England. However, the Earl’s pacifistic stance and eventual sitting in the Jacobite Parliament meant he could not simply have him executed, nor even utterly attained without some consequence. That left exile. The Duke-regent had the Earl not stripped of his title, but granted a new one: he would become 1st Earl of Long Island, the second peerage to be created under the Acts in the New World. Furthermore, it was ordered that the Earl actually live in Long Island, given that he was also created Governor of New York since the death of his predecessor in the Second Metacom War. Given the man was almost 70, many expected he would last only a handful of months. Initially, his son and family would stay in England, but after said son died from poisoning not many days before the Earl’s voyage, his wife and son would join Shaftesbury to go to the New World. Ironically, Shaftesbury would live to almost 90, and became a well-liked and respected leader of the colony; by the end of his life, what was not owned or influenced by the Van Haarlems was owned or influenced by the Ashley-Coopers. As for the Duke of Monmouth, his general loyalism was to be rewarded, if only because not doing so was feared to lead to more chaos and fighting. He was officially legitimized, and was made scion of the cadet branch of the House of Stuart, known as the House of Stuart-Scott[10]. Perhaps luckily, he would die in 1692 of fever, before he had truly consolidated much political influence again.”

“DIVINIST [dih-vahyn-ist]: (i.) A form of government in which a singular leader holds final say on all matters of state, both with or without the approval of a legislature, with the justification of holding the divine blessing of a deity to do so. Often accompanied by strong state church. Variant of Totalism. EXAMPLES: King Charles I, King Richard IV, King Richard V of England; King Louis XIV, Louis XV of France

…

POPULIST [pohp-yuhl-ist]: (i.) A form of government in which a singular leader holds final say on all matters of state, typically with a legislature over which they hold themselves as a balance to, with the justification that they do so to protect the citizens of the state from both aristocratic and democratic tyranny. Variant of Totalism. EXAMPLES: King Richard IV of England; Chancellor James Fort of Cavelieria; Vozhd Ivan Borisov of Slavia

…

TOTALIST [toh-tahl-ist]: (i.) A form of government in which a singular leader holds final say on all matters of state, typically without any form of legislature, with the justification of tradition or the stability of the state. EXAMPLES: King Charles II of England; King Louis XIV of France; Kaiser Heinrich II of Germany

…

VOLKSPICION [vohl-kz-spish-ohn]: (c.) The belief in a particular group as being inherently politically untrustworthy or hostile to the state; adj. form: VOLKSPICIOUS. Constructed term from the German volk, meaning a group of distinct people, and the English suspicion, meaning to hold distrust and be critical of. EXAMPLES: The Scottish Suppression (motivated by), The Great Purges (motivated by), Anti-Catholicism, Anti-Judeaism, Dusting Occupation (motivated by)”

“The end of the Bloody Year in England provided the Duke of York a golden opportunity; due to the conflict, to be fervently anti-Catholic was to be traitorous, to be republican was to be traitorous, but to be Catholic or royalist was to be above reproach in loyalty. The situation would not last, not with a majority of the realm being Protestant, and a general trend against totalist rule. Soon enough, the Crofts would grow and the Abhors would begin to clarify their loyalty to the king, not the regent. And so the Duke seized the immediate opportunity to create Catholic lords and to execute or exile political enemies, while raising friends and allies. Perhaps most importantly, he had the Test Acts repealed, and had the Oath of Supremacy made purely political.[13] He also had the Christian Discrimination Act forced through, which penalized the persecution of Catholics by Protestants, but also penalized the persecution of Protestants by Catholics. Though the people were ever-reminded of how their young, Protestant prince was saved from the cruel Monmouthites, and that once he reached his majority in 1697, he would reign as full king, Parliament was under no illusion: their monarch for the time being was James II & IV, and his political power would far outreach his regency.

But James was not tyrannical, nor an ill-ruler. Despite suggestions against it, he allowed a fair Parliament to form, with Crofts and Abhors alike, and when both groups began to criticize him, he utilized the neutrals and moderates, led by future Supreme Chancellor Robert Spencer, Earl of Sunderland, to propose his ideas as compromises between the two sides, often with caveats for more religious tolerance being buried inbetween concessions to either factions. James was also very frugal, and while extensive rebuilding of England and Ireland (notably less so in Scotland) would occur, he remained ever conscious of both the Crown’s wealth and that of the state’s, meticulously going over finances even after the regency, and (perhaps apocryphally) stated, “A country in debt is a country that will fail.” His skill in politics, or perhaps that of his advisors (in which case he excelled in picking them), helped keep the country moving to his designs, such as the appointment of politically tolerant bishops after a mass purge following the war, and when he had the work of John Locke and Thomas Hobbes printed (or re-printed in Hobbes’ case) and circulated widely. Locke, once politically Anti-Catholic, printing work that some felt leaned republican, had become jaded by the events of 1687, in which he had been imprisoned by the Small Parliament for speaking out against their ‘legislation’ that effectively illegalized Catholicism. After escaping, he would hide in a loyalist town that was pillaged by a rebel army for supplies and and then plagued by bandits afterwards. In 1689, he published his new treatise On Government, Without Delusion, which ‘corrected’ his old beliefs by stating that law and order were paramount, and that any alternative to present government must itself be ‘reasonable and developed’ before it had any right to attempt to usurp the present law, and had to first be embraced as holding the ‘populace’s will,’ at which point the current government’s resistance to that will was itself the cause of disorder; importantly, to hold the populace’s will was promoting the common good of all ‘orderly’ groups in society, not simply holding majority support. Given Locke’s loyalism, which established the moderate government of the Duke as the one that truly held the will and all forms of extremist rebellion as being false agents of chaos, it was little surprise that his work was proliferated.[14]

Perhaps ironically, the popularity of Locke also allowed for resurgence of the republican philosopher Algernon Sydney, who was spared after the conflict, despite his work being ruled as treasonous by members of Parliament. Although Sydney would live out his days in exile amongst the Dutch, his work, Discourses on Government, was still in print, as it heavily implied that the Monmouthites had failed because they had failed to gain the will of the people, meaning said will was with the loyalist and thus the Crown, especially with how beloved the young Richard was. However, he argued strongly that should any ruler become harmful to their people, they had the right to change their government freely, and further argued that the rebellion was ultimately a positive event in that it first reminded the official government that they could not act without considering public opinion, and then illustrated via the failure of the rebel government that oppression of the masses was not a means for success. This tangent, however, shows that even his enemies saw that the Duke’s control of the nation was firm at the time.”[15]

“...General Bacon left Virginia to impress his lord, and came back one himself. The new governor saw it that his new title and office were official, royal acquiescence to his wishes for a Virginia free of novans. The men who had come with him from England, the retroactively dubbed 1st Cavalier Rifleman, became instrumental in these plans, especially as many of them, now heroes and knights, went back to their homes and spread a patriotic fervor. In Carolina, the populace was suddenly calling for a Baconian policy of expansion, and it wasn’t long before the Frontier March was on. Novans, particularly in Virginia as Carolina established exemptions for allied tribes, gained a total kill-on-sight status, regardless of origin or activity. Many tribes resisted and fought back, but the over the next thirty years the frontier was slowly pressed back, novan corpses under colonial boots. Soon enough fear outgrew hate, and the survivors left or circumvented any settlements they knew of, which inevitably brought inter-tribe conflicts, hastening their demise.

This expansion was itself fuelled by the Bloody Year’s exiles, including numerous Covenanters from Scotland (to Carolina), and attained former lords of England (to Virginia) who brought with them wealth and followers, as those who lost all in the conflict sought a new life. But with this arrival of immigration, there came a few problems. Most, for instance, were unable to afford settling the frontier, or lacked sufficient knowledge of farming and construction, but had not enough funds to hire others. And so the Governor began to expand the institution of indentured servitude. New arrivals would labor for, on average, five years before being released of their bondage and granted a small sum, which would then be used to build a homestead, whose lands would then be worked by servants that banded together, and eventually they would then offer their fields to indentured work for those who wanted land further. Eventually, once Virginia truly had a border, this process came to an end, but indentured servitude did not. Annual contracts were common, with renewal, and many agreed to work a year for simple shelter and food, though a meager ‘allowance’ of spending money was often granted by wealthier estates. Meanwhile, slavery began to wither away, as permanent care of slaves from birth to death, alongside both the existence of government tax that indenturers were free from, and the presence of many former slaves in positions of local prominence due to Bacon’s Coup, made slavery a less profitable and less politically promoted institution.

Perhaps another consequence of the indentured system, and thus of the Bloody Year, was the large amount of wealthy mulattos in Virginia. Ex-slaves of African descent would go to the frontier, or would be part of the ‘manor-family’ of the formerly indentured, and more than a few would marry whites. Adding to this were the numerous escaped slaves of Spanish colonies who would go to Virginia and become indentured.[16] In contrast, Carolina, which did copy the support for indentured servitude, but had not seen its slaver society challenged, saw a handful of black and white indentured establish plantations of their own, in which they would indenture overseers but purchase slaves, creating a far more firm and distanced cultural elite even in the frontier, and miscesanguination was far less common, and often discouraged by all parties. It would be in this period that the terms ‘negro’ and ‘nigrar’ would begin to develop and diverge, the former coming the mean black aristocratic elite, and the latter meaning uneducated slaves. Its pejorative use against the poor and unskilled would see nigrar come to mean most in the low strata, while ‘blainco’ would join negro to be one of the dual terms for the high strata, being for white families, but all of this did not begin for many years to come…[17]