1st January 1943 – The Turning of the Tide – Part IV – The USSR

Garrison

Donor

1st January 1943 – The Turning of the Tide – Part IV – The USSR

The USSR had held out in the face of the largest military operation in history when they defeated Operation Barbarossa and faced another titanic series of battles as they fought to contain Case Blue. By January 1943 the German 6th Army was surrounded at Stalingrad and doomed to destruction, whatever the propaganda from Berlin might say to the contrary. These victories had come at a high price and even as the soldiers of 6th Army starved and froze at Stalingrad the citizens of Leningrad faced the same threats as their city remained besieged, and the Germans remained in control of the most productive farmlands in the Soviet Union, meaning that even as the Soviet leadership demanded ever greater output from their industries the workers went hungry on a regular basis. Despite the losses inflicted on the Wehrmacht in 1942 the Soviet leadership had to consider the possibility that Germany would somehow muster the means to launch another major campaign in 1943 and there was no certainty that they wouldn’t succeed this time, however confident Stalin might be in public about the superiority of the Communist system over their Fascist enemies and the inevitability of victory privately they could not ignore this possibility. In addition to extolling the virtues of the Soviet system the efforts to bolster the spirit of the population turned to much older rhetoric, with calls to fight for ‘Mother Russia’ being sprinkled in amongst the Marxist dialectic and even the Orthodox Church, long despised by the Communists, was partially rehabilitated to rally those who still secretly placed their faith in God rather than the Socialist revolution [1].

The massive effort to relocate industry from western Russia to place it beyond the reach of the Germans had been completed, but the movement of raw materials and finished goods beyond the Urals were serious issues that increased the constraints on Soviet production. Even if they had been able to run at maximum efficiency Soviet industry would have struggled to provide the volume of weapons needed to build up the Red Army and replace its combat losses, never mind all the ancillary items needed to support its operations and as for civilian production it came a distant third, when it was considered at all. The Katyusha rocket system has become one of the famous weapons used by the Soviets during the war and it became so ubiquitous in no small because it didn’t demand the high-quality steels and fine manufacturing tolerances required in the production of large artillery pieces and it was symbolic of much of Soviet arms production, where quantity was always a higher priority than quality. Better after all to put a poor rifle in the hands of a soldier than no rifle at all. This also explains why the Soviets accepted large quantities of British and American hardware that were regarded as out of date or inferior, at least according to the official reports of the Red Army, which were usually written by officers who had the NKVD breathing down their necks. In many cases the tanks and aircraft shipped to the USSR, at great risk to the crews of the merchant ships on the Arctic convoys, were as effective as their Soviet equivalents and helped maintain the strength of the Red Army. Even where Soviet equipment was truly superior there were still problems [2].

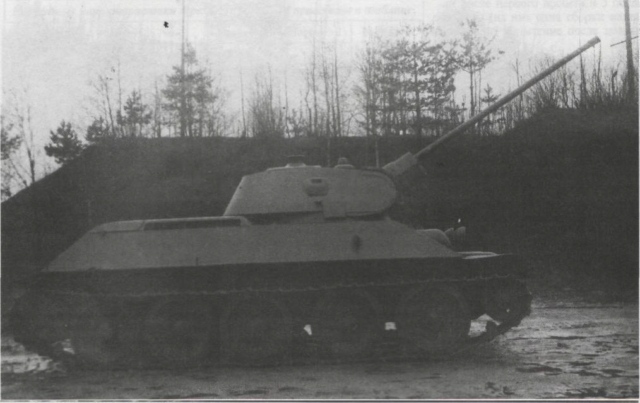

The T-34 became the iconic symbol of the war in the east and the Soviet fightback against the Nazis, forging its legend in the counterattack at Moscow. Like most legends while there was a substantial kernel of truth to the accounts there was a great deal of mythology that grew up around its prowess on the battlefield in the name of propaganda. The sloped armour of the T-34, broad tracks, and a decent 76mm gun made it a capable machine, it must be noted though that one of its major advantages during the counterattack at Moscow had lain in the fact that it was well adapted to the conditions of the Russian winter where its opponents were not. It was also a fact that most of those opponents had been obsolescent Panzer Is and IIs. Even the Panzer III, the tank intended to make up the bulk of the German Panzer Divisions once enough could be produced, was usually equipped with the then standard German 37mm gun anti-tank gun, with the 50mm armed version a rarity in the winter of 1941 and the long-barrelled 75mm armed Panzer IV even more so [3]. The armour arrangement of the T-34 was certainly an improvement over the square and rather boxy layout of many western tanks, but it should be remembered that the Pak 36 37mm anti-tank gun struggled just as much against the Matilda and the Valentine in 1940 as it did against the T-34 in 1941. By the latter half of 1942 the Red Army was encountering 50 and 75mm anti-tank guns mounted on German armour on a regular basis, and the German tanks had also received armour upgrades that negated some of the power of the T-34’s own main armament. The T-34 might have become a legend, but it was one in serious need of some upgrades and improvements in 1943 if it was to remain effective on the battlefield. There was also the need to produce newer revisions of the KV/IS series of heavy tanks, to counter the expected arrival of tanks like the Tiger in large numbers, not to mention to demonstrate the Soviet Union could overmatch new western models like the A24 Churchill [4].

All of the above provides the context for why the Soviets were so eager to see more materiel supplied via Lend-Lease and the opening of a second front in Europe. It is easy to think of the Soviets demands for the second front as being mostly political posturing on the part of Stalin. This though is to ignore the fact that there was though a genuine resentment in many quarters that the Western Allies were ‘doing nothing’ while the Red Army fought and bled to destroy the Wehrmacht. In 1938 and 1939 Stalin had chosen to side with the Germans not simply because the Nazis were willing to offer more, but because he feared that the Allies simply wanted to use the Red Army as cannon fodder, allowing them to sit to one side while Germany and the USSR exhausted themselves and paved the way for the British and French to carve up Germany and Russia between them. As 1943 opened it did not seem unreasonable to believe that the capitalist nations were still pursuing the same plan, leaving the Soviets to carry most of the weight of fighting the Nazis while they concentrated on protecting their colonial possessions. from this viewpoint the campaigns in North Africa and the Mediterranean were an irrelevance, minor distractions at most to the Germans and ones that had not stopped Hitler launching Barbarossa and Case Blue. The attack on Dieppe was likewise regarded as a dismal failure and the reassurances from London and Washington that there would a major landing in France in 1943 were greeted with considerable scepticism in the Kremlin. The war in the Pacific was regarded as an even greater folly, the product of the Western Allies gravely underestimating the Japanese war machine [5].

The Soviet Union had fought its own battles with the Japanese but for now they were content to respect the non-aggression pact they had signed with the Japanese after the fighting at Khalkin Gol and the Japanese were happy to reciprocate neither party needed the complications of fighting on a second front and Stalin would rebuff any calls from the Americans and the British to repudiate the pact and declare war on Japan. Stalin was not going to be distracted by secondary concerns, the Japanese could be dealt with in due course if the Americans and British didn’t finish them off first. The primary goals of the USSR were the destruction of Nazi Germany and the seizure of territory in the west to create a buffer zone between the USSR and their capitalist enemies. Stalin was not, despite claims to the contrary later, planning a wholesale conquest of Western Europe. If it was possible to export the revolution to the likes of France and Italy, Stalin would not pass up the opportunity, he had no intention however of driving his nation to the brink of collapse trying to reach the Mediterranean and the Atlantic. If the Western Allies finally bestirred themselves and drove the Germans out of France and restored it to capitalist control then he was content to accept that outcome, his ultimate goal was Berlin, not Paris [6].

What the Soviets wanted above in 1943 was for the Western Allies to provide them with the tools needed to destroy the Nazis, which meant not only weapons and equipment, but also British and American troops fighting in the main theatre of the war [7].

[1] Stalin is willing to embrace anything to bolster fighting spirit and save his own hide, once the war is won you can expect a backlash. The average Soviet worker is only better off than those working as German slaves in that Stalin doesn’t actually want to work them to death, that’s reserved for those in the gulags.

[2] Basically pretty much as per OTL, they are desperate for every tank, gun, and airplane they can get, even if they don’t show a lot of official gratitude for it.

[3] It’s a good tank, but its capabilities were overstated in OTL, in the same way that the Sherman was greatly underrated.

[4] So overall Soviet armoured losses were worse ITTL 1942 and German losses that bit lighter, and with no Afrika Korps there will be some extra men and equipment for the Eastern Front in 1943. The balance of events will therefore see some incremental changes that build up towards the time of Operation Citadel.

[5] While the Soviets do have a point to some degree about the need for a proper second front Stalin’s complaining after the Allies made it clear there will be a full-scale landing in 1943 is not making him any friends.

[6] So no, I don’t accept the idea that Stalin was prepared to go all in on a conquest of Europe, once the Germans are done the rest can take care of themselves and if they should happen to look to Moscow for leadership, so much the better.

[7] Coming soon to a beach, or five, in Normandy…

Last edited: