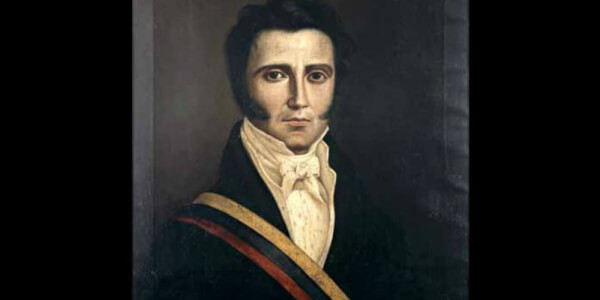

Following the Colombian victory in the Colombo-Peruvian War, President of the Republic Francisco de Paula Santander decided to start what is known as the Great Reforms, a series of decrees that transformed the Colombian republic by promoting education, immigration and reforming land ownership. He would also approve the Second National Constitution. Santander’s presidency would be a peaceful time of grow for Colombia. He handed the presidency to Marshal Antonio Jose de Sucre, the victor of Tarqui.

Sucre was faced with a first great challenge when the puppet dictator of Haiti, Leroy, died, starting a rebellion that threatened to break the Colombian hold of the little nation. This Caribbean Crisis shook Colombian prestige and power, but Sucre was eventually able to restore control and calm the situation for the time being. But his greatest test came when a great earthquake hit Caracas, starting a period known as La Violencia. The Federal government tried to dissolve the Venezuela state government to deal with the crisis, but the Centralist Party opposed the effort. This cleaved the opposition in two, with Esteban Cruz’s moderate faction, the Marchitos, leaving and becoming the National Conservative Party or PCN, while Juan Jose Flores’ reactionary Espinas remained.

When the 1840 elections returned a divided result, Cruz and his men elected Sucre again. But the government was powerless due to a divided Congress. The situation only took a turn for the worse after Sucre was assassinated by far-right guerrillas. When Congress rejected his Vice-president, Colombia was left without a leader. After a second election returned the same divided result, Flores launched a coup attempt, which failed to gather enough support. In response, Cruz and the remaining members of Congress formed a National Emergency Government or GEN. Prestigious General Lorenzo Rodriguez was elected as Provisional President due to his popularity with the troops, especially the men of the Southern District Army, the only effective command in Colombia.

Rodriguez and Cruz defeated Flores and his rival government in Maracay. They were aided by Bolivar, who wrote a letter disowning Flores and his government from Paraguay. After this, the government passed emergency decrees to reconstruct Caracas and amend several points of the National Constitution. Cruz would be elected president in the elections of 1842, and reelected in 1850. Like Santander, he would be a hugely important figure in Colombian history, with his presence channeling the Colombian Conservatives into an effort for building industry and modernizing the country. Several companies such as the Andean Railway Company, the Colombian Arms Manufacturer and the Colombo-Peruvian Guano Company were funded under Cruz, who also massively expanded Colombia’s railways and education system.

Cruz would also mark a shift towards a more aggressive and imperialistic Colombian foreign policy. He meddled in the Pacific War, and the Triple War. The first was a war between the Peruvian-Charkean alliance and Chile. Chile had just gone through a civil war, the War of the Colors, which ended with a Liberal victory. But this convinced Charkas, under a dictatorship, and Peru, to try and wage war for Chile’s coastline, more specifically their guano. With Colombia distracted due to the Great Crisis, the alliance declared war. Colombia, as soon as it recovered, meddled by selling weapons to both sides, before intervening in the peace process once Charkas lost the war military and Peru fell victim to its own revolution. Chile expanded, taking most of the coast, but Charkas retained a small strip of land known as the Charkean corridor.

The revolution that forced Peru out of the war was called La Gloriosa. It was started by Juan Carlos Medina, a veteran soldier who took advantage of indigenous discontent to form an army that eventually defeated the dictator Santa Cruz. Medina’s new regime started several massive social reforms, though he fell short in some aspects. He also allied the country with Colombia, providing for Colombian domination of the South American pacific. Chile, for her part, went through political turmoil which divided the conservative sides. The addition of laborism as a pro-worker ideology further muddled the questions that faced the nation, including the Cuestion del Sacristan, which led to a conservative alliance in the form of the Mott-Varista Party. Mott, the new president, would similarly to Cruz led Chile in a new imperialistic and industrialist path.

The Triple War was a conflict between Imperial Brazil, La Plata and Paraguay for domination of the Southern Cone’s politics, the basin of the Rio de la Plata, and more importantly, Oriental Provinces. The campaign for Oriental Provinces was characterized by a back and forth, with neither Brazil nor La Plata being able to establish dominance. Paraguay held steady, defeating invasions by both thanks in part to Simon Bolivar, who had gone to the nation and now offered it its services as commander of the army. The lengthening war eventually led to the Farrapos Revolution in Rio Grande do Sul. Esteban Cruz took advantage of it by organizing the Oriental Mission to supply the rebels. Brazil would eventually admit defeat after a coup d’état forced Emperor Dom Pedro II to abdicate, leaving the country under the control of a military junta headed by the Monarchist Marques de Sousa. La Plata maintained control of Oriental Provinces, but the national government was overthrown by the governor of Buenos Aires, Juan Manuel de Rosas, who installed himself as dictator.

South America was not the only zone under conflict. Tensions between Mexico and the US increased throughout the years due to American ambition on the great Mexican north. The government of Lewis Cass was belligerent, but it didn’t act upon these threats, while Mexico lived a peaceful era under the leadership of Emperor Agustin II. But Cass was assassinated, and the US was unable to determine who was going to be president. The Vice-president was selected as provisional president only, and elections were called. The populist Democrat James K. Polk, who promised war against Mexico, won. True to his words, he declared war on the Mexican Empire in 1851, starting the Mexican-American War.

The first campaign of the war took place in Louisiana, where Mexican General Luis Guillermo Ruiz was able to push the Americans back and, in a masterful campaign, he started an invasion of the US state. Mexico was aided by France, which, now under the lead of Napoleon III, was looking for ways of increasing its prestige and world standing. The French Navy defeated the Americans and prevented them from supplying New Orleans, forcing American General Zachary Taylor to surrender the city and his army. Ruiz would occupy Louisiana for a year in what the Americans called the Rape of Louisiana.

Decided to find another way of ending the war, Polk approved an amphibious invasion of Veracruz. Simultaneously, an invasion of California took place. The California invasion would be successful, with the Americans taking the territory, including the capital of Yerba Buena. General Lombardini’s attempt to defeat the Commodore McLain was a disaster, his army dissolving after their defeat at Mount Diablo. But Veracruz turned into an American disaster due to a falling supply. At first, the situation seemed promising, with the invading Frog Army being able to make a beachhead. General Zapatero resisted valiantly, but he felt in battle, and his successor, Veintimilla, suffered a nervous breakdown. General Marco Antonio Salazar took command and would eventually force the American commander, Robert Patterson, to surrender. A part of the Frog Army managed to evacuate thanks to the daring efforts of Robert E. Lee and George B. McClellan.

American morale was preserved only thanks to General Winfield Scott, who managed to vanquish Ruiz. This came after a series of failures, such as General Butler’s First Battle of the Mississippi, which was a bloody disaster. Scott, however, learned, and he was able to defeat Ruiz in the battles of Avoyelles Courthouse and Baton Rouge. Ruiz evacuated Louisiana, but he would fall in battle. The second in command, General Valencia, would take over and lead the army back to Texas, which was under a state of upheaval.

Mexico was in a similar state. The death of Emperor Agustin II, and the fall of the government of Eduardo Castillo sowed confusion. A Mayan rebellion joined economic collapse, and eventually threatened political turmoil. Salazar, now a Marshal of Mexico, led a coup under the terms of his Plan of Veracruz. This installed Princess Isabel as Regent and created a Council, headed, of course, by Salazar. Parliament was dissolved for the moment. Meanwhile, the pro-peace Liberal opposition won the midterms in the US. Scott continued advancing in Texas, but was eventually stopped in El Alamo. This was the final straw for the Americans, who demanded peace. Reluctantly, Polk agreed and both nations signed the Treaty of la Habana. Mexico ceded the land in exchange of payment.

Mexico lost the war, but won the peace. Salazar’s new government was stable, and after some time he called for elections. His government passed significative reforms that advanced the modernization of the Mexican state. He granted independence to the Central Americans, who, unhappy with Mexican control, revolted at the same time as the Mayans. The new Central American Republic would quickly fall under Colombian domination. Similarly, Rosas’ dictatorship fell in La Plata, leading to the Federal Compromise that restored democracy as a federal republic, while the Braganzas returned to Brazil, restoring the monarchy and opening the path for progress. The US lost the peace, with the new lands putting the dangerous slavery question at the front of the national stage. Civil War seemed to be in the horizon.

While this took place in the Americas, Europe went through the 1850 Revolutions. Started by discontent, new laborist, liberal and national ideas and notions, these revolutions led to several heavy changes. In France, the Citizen King fell and Louis Napoleon Bonaparte took his place as head of state, becoming Napoleon III, Emperor of the French. The Hungarian Revolution led to the collapse of the Hapsburg Empire, but this opened the door for unification with Southern Germany. Prussia resisted the liberal reforms, but it managed to unify with Northern Germany, thus creating two German nations. A similar split happened in Italy between a monarchical Northern Italy and a Southern Italy republic, one heavily influenced by the Pope. Russia watched over these revolutions, supporting Hungary, and also intervening to liberate Romania. Tsar Constantin would join France’s and South Germany’s war against North Germany, resulting in a French victory that confirmed French dominance in continental Europe, something that alarmed Britain.

France and Britain would then start a kind of cold war, including proxy wars, such as the Japanese Revolution that pitied the Shogun and the Emperor. The Shogun, supported by France, won the war and started to modernize the country. Britain had, many years before, extended its influence in Asia by winning the Opium War and taking Hong Kong.

Returning to Colombia, Juan Roberto Diaz, from the PCN, was elected President of the Republic. But the Federalist controlled Congress opposed his every move. A big economic crash due to a bank failure and low sugar prices in Hispaniola devolved into a political crisis, known as the Decade of Sorrow. The emergence of the social movement known as Young Colombia, which clamored for rights and reform, further hindered the Diaz administration.

Diaz would lose reelection to the Federalist Luis Bonifaz. But Bonifaz was a weak leader who couldn’t maintain his party united. The Federalists would split between the conservative Democrats and the reform-oriented Liberals after several events, such as the execution of Chiluisa in Quito and the famed attempt to defend him by a group of lawyers known as the Quito Five. This event would bring indigenous rights to the forefront of national politics. The issue only grew when an indigenous man, Ordoñez, challenged the state for his voting rights in the case Ordoñez v. Ecuador, which reached the supreme court. Right now Colombia is headed for elections in 1858, with an air of uncertainty enveloping the nation.