You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Miranda's Dream. ¡Por una Latino América fuerte!.- A Gran Colombia TL

- Thread starter Red_Galiray

- Start date

- Status

- Not open for further replies.

Threadmarks

View all 76 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 62: The Balkan War Chapter 63: The Liberal Revolution Appendix: The Colombian National Army Appendix: The Colombian Cavalry Appendix: The Colombian Artillery Appendix: The Colombian Navy Chapter 64: From the Andes to the Caribbean Chapter 65: The Irrepressible ConflictSeems like Colombia is heading in a direction that will lead it to become a much more egalitarian society be it through slightly racist ideas. I find it interesting that the country is industrializing so effectively and quickly without most of the negative drawbacks that other countries that industrialized had to deal with. I think the set up of having medicine and medical education be widely accepted in the country and the implementation of a massive city-wide organization and planning strategy for the major cities will help the country a lot int he long run.

Deleted member 67076

Most likely. The Tanzimat land reform caused a population explosion but it also led to the loss of common land and the creation of a big landed elite. Peasants now have more incentive to either move to the cities or to emigrate.Will we see a lot of Arabs coming in like OTL?

So lots of big changes here. The development of an internal market through rail building and an established middle class (or classes I should say given a rail baron and a clerk are both technically in the same group who can buy from the domestic market) sees the development of a healthy and rapidly expanding economy thats sure to probably enter the Second Industrialization period pretty easily. And with gusto given the chemical industry will have all those cheap local minerals to use.

At the same time demand for labor has gone up, leading to massive amounts of immigration (probably with a brief boom as America and Mexico are uh, occupied burning each other to the ground). Land settlement policies areare encouraging that too, though given how the land is most of the mountains and highlands would be more Native and European, while the lowlands more Indian and Caribbean Black. Probably too early to get the similar 1880s boom of West Indian cheap labor given that happened after a turn of the century sugar bust (and international sugar is just picking up again) but the seeds of migration have been planted there, so to speak.

Speaking of sugar, Colombian Hispaniola's sugar industry won't be doing too hot after this. From what Ive read and looking at the historical trajectory, its mostly clustered in the southern plains (RIP rancher barons, we wont miss you) and though continually buffed with investment and stability, its going to be facing much more competition which will depress costs. Probably gonna spike unemployment given the seasonal nature of sugar too. The south department is probably going to need a state bailout in a decade or so.

But hey, the Cibao north should still be fine. Tobacco, lumber, and cottage industries pay less but they never falter. Especially now that they got access to loans from the banks in Cartagena or Caracas.

Haiti though is going to burst pretty badly. New class of educated nationalists and it just being increasingly richer and more well aware of the realities. The release valve of using citizens there to settle the Colombian lowlands can only work for so long.

Also regarding social changes, tons of them are happening. Early feminist thought, racial and social liberalism competing with economic realities and old prejudices that never went away, and culture clash of immigrants from around the world all trying to both assimilate and stay autonomous.

Would lead to some great literatuee exploring all these ideas.

Anyway thats just me spitballing comments.

And is too early for sodas so yeah a crash will come and will not be pretty but as you know as dominican,both La Española nations have develop like 50 years ahead of schedule and as you say, not cattle barons will benefit the environment in the long term too, but yeah sugar will be a product but less demanded and a lot of haciendas will convert into subsistence farming during the crisis. Haiti is a time bomb Colombia would need to address.Speaking of sugar, Colombian Hispaniola's sugar industry won't be doing too hot after this. From what Ive read and looking at the historical trajectory, its mostly clustered in the southern plains (RIP rancher barons, we wont miss you) and though continually buffed with investment and stability, its going to be facing much more competition which will depress costs. Probably gonna spike unemployment given the seasonal nature of sugar too. The south department is probably going to need a state bailout in a decade or so.

That is why a Colombian Spring?(or summer?) is coming and will be the sociopolitical and cultural change of the nation.Also regarding social changes, tons of them are happening. Early feminist thought, racial and social liberalism competing with economic realities and old prejudices that never went away, and culture clash of immigrants from around the world all trying to both assimilate and stay autonomous.

Would lead to some great literatuee exploring all these ideas.

that would be 50 years on schedule, colombia got a lot of former ottomans from ww1. that will be a big butterfly.Most likely. The Tanzimat land reform caused a population explosion but it also led to the loss of common land and the creation of a big landed elite. Peasants now have more incentive to either move to the cities or to emigrate.

So the mixed race population of Columbia will grow to outnumber the separated ethnicity eventually? That'd be nice, it'll be a blow to any simmering racism and the girls will be hot! Seems like Brazil will have competition. Hopefully Argentina also follows this type of "whitening" if they go about it TTL as well, it'd be much better than the genocide of OTL.

I think that kind of "whitening" did happen in Argentina and most Latin American Countries and just made people hypocritically racist, I mean, racist while fighting to hide Indian or black ancestry....and I don't know about you, but to me, Colombian women are indeed smoking hot!!!

Argentinian Whitening was waging a genocidal campaign on their non-white population while increasing immigration from Europe.I think that kind of "whitening" did happen in Argentina and most Latin American Countries and just made people hypocritically racist, I mean, racist while fighting to hide Indian or black ancestry....and I don't know about you, but to me, Colombian women are indeed smoking hot!!!

Well, beauty is suggestive after all. Just don't get between me and my Cape Verdean goddesses.

Will we see a lot of Arabs coming in like OTL?

Oh, I knew there was a minority I was forgetting. Yeah, the Ottoman Empire is feeling a little under the water due to the French and Russians meddling more there. That has created economic instability and with the United States at war and the generous land opportunities, Colombia is looking pretty sweet. However, since Colombia puts more emphasis on being Christian, and on being the right kind of Christian at that, it's mostly the Levanant Christians who are coming rather than the Muslim population.

Colombia own puerto rico, making Haití a state would give them direct funding alongside a voice and vote yet they already defacto ruled it, hope is not like OTL puerto rico and might get accepted in the future.

A Colombia spring like the european ones? Would be interesting

The question is whether the Colombians want Haiti to have a voice in the first place. Yes, it would be an interesting scenario, though it wouldn't be a springtime of nations but one of ideas.

So the mixed race population of Columbia will grow to outnumber the separated ethnicity eventually? That'd be nice, it'll be a blow to any simmering racism and the girls will be hot! Seems like Brazil will have competition. Hopefully Argentina also follows this type of "whitening" if they go about it TTL as well, it'd be much better than the genocide of OTL.

Haiti will probably seek it's own destiny once Columbia's issues force it to turns inward.

Most are mestizos already. Even in OTL most of the people in the region are mestizos. Of course, the degree of mestizaje varies. And the girls will be hot. Argentina (or La Plata ITTL) is probably going to do it the gringo way, sadly. Another sad fact is that Haiti for itself doesn't have much of a destiny, since Colombia has made sure that they can't survive without their exports of food and industrial goods and no other nation is going to help them, so the Haitians probably will retain a close relationship to the Colombians.

Not much to comment on, but nice to see the TL back.

Thanks!

This the Columbia TL I didn't know I needed in my life.

I haven't quite finished to catch up, but I wanted to say you're doing an awesome job!

Thank you very much! You don't really see that many Colombia TLs, or even Latin America centric TLs around here.

Seems like Colombia is heading in a direction that will lead it to become a much more egalitarian society be it through slightly racist ideas. I find it interesting that the country is industrializing so effectively and quickly without most of the negative drawbacks that other countries that industrialized had to deal with. I think the set up of having medicine and medical education be widely accepted in the country and the implementation of a massive city-wide organization and planning strategy for the major cities will help the country a lot int he long run.

My own analysis of American industrialization has led me to believe that the main problems of the process in the Americas would be disaffection over industry replacing farm labor and the subsequent "wage slavery" rather than the European problems of Luditism and extreme poverty. I concluded this because both the United States and correctly administered Colombia or Mexico have enough land to give to immigrants and laborers, and technological progress is more welcomed. This prevents or mitigates issues such as widespread unemployment or backlash against new technologies and techniques. Now, Colombia has many problems with its industry, namely that it is mostly British owned and of inferior quality, but I will explore that more in the future. By the way, the medical developments are being adopted through Latin America and Mexico will probably undertake efforts of its own to reorganize its cities after the Mexican-American War.

Most likely. The Tanzimat land reform caused a population explosion but it also led to the loss of common land and the creation of a big landed elite. Peasants now have more incentive to either move to the cities or to emigrate.

So lots of big changes here. The development of an internal market through rail building and an established middle class (or classes I should say given a rail baron and a clerk are both technically in the same group who can buy from the domestic market) sees the development of a healthy and rapidly expanding economy thats sure to probably enter the Second Industrialization period pretty easily. And with gusto given the chemical industry will have all those cheap local minerals to use.

At the same time demand for labor has gone up, leading to massive amounts of immigration (probably with a brief boom as America and Mexico are uh, occupied burning each other to the ground). Land settlement policies areare encouraging that too, though given how the land is most of the mountains and highlands would be more Native and European, while the lowlands more Indian and Caribbean Black. Probably too early to get the similar 1880s boom of West Indian cheap labor given that happened after a turn of the century sugar bust (and international sugar is just picking up again) but the seeds of migration have been planted there, so to speak.

Speaking of sugar, Colombian Hispaniola's sugar industry won't be doing too hot after this. From what Ive read and looking at the historical trajectory, its mostly clustered in the southern plains (RIP rancher barons, we wont miss you) and though continually buffed with investment and stability, its going to be facing much more competition which will depress costs. Probably gonna spike unemployment given the seasonal nature of sugar too. The south department is probably going to need a state bailout in a decade or so.

But hey, the Cibao north should still be fine. Tobacco, lumber, and cottage industries pay less but they never falter. Especially now that they got access to loans from the banks in Cartagena or Caracas.

Haiti though is going to burst pretty badly. New class of educated nationalists and it just being increasingly richer and more well aware of the realities. The release valve of using citizens there to settle the Colombian lowlands can only work for so long.

Also regarding social changes, tons of them are happening. Early feminist thought, racial and social liberalism competing with economic realities and old prejudices that never went away, and culture clash of immigrants from around the world all trying to both assimilate and stay autonomous.

Would lead to some great literatuee exploring all these ideas.

Anyway thats just me spitballing comments.

The Chemical Industry is poised to overtake the Metallurgical, Textile and Arms Industries due to Colombian and British interest in and control over Peruvian and Chilean Nitrates. As for the settlement, yes, that's a pretty accurate description of the future ethnic make-up of the region, but its counterbalanced by a Mestizo movement to coastal areas due to the boom of commodities such as cotton, banano, coffee and cacao. Sugar is going to crash soon because Spain finally got its game together and Cuba is producing again. And that's been going on for at least a decade.

The Colombian elites are basically clinging to old colonial hierarchies that can't simply survive in a modernizing nation such as Colombia, especially now that most have developed ideas of exceptionalism. I've been meaning to write an appendix about Latin American culture from the Independence to now but I haven't found the inspiration... Perhaps in the future.

And is too early for sodas so yeah a crash will come and will not be pretty but as you know as dominican,both La Española nations have develop like 50 years ahead of schedule and as you say, not cattle barons will benefit the environment in the long term too, but yeah sugar will be a product but less demanded and a lot of haciendas will convert into subsistence farming during the crisis. Haiti is a time bomb Colombia would need to address.

That is why a Colombian Spring?(or summer?) is coming and will be the sociopolitical and cultural change of the nation.

that would be 50 years on schedule, colombia got a lot of former ottomans from ww1. that will be a big butterfly.

The beef industry of Hispaniola has dissapeared due to Venezuelan control over it. And these far more competent governments will probably better administer the islands' resources. As I said earlier, not many Muslims yet, but in the future they will probably come in droves.

Soooo, at the risk of being annoying, I'm going to ask, how's Cuba doing under Spanish rule? I can't wait to have people in the island crying "¡Viva Cuba Libre!" and "¡Al Machete!"

Soon my friend. Spain has got its game together and Cuba is producing sugar again, but now the US, Colombia and Mexico are all eyeing the island for their own reasons. Within the Island itself, the success of Mexico and Colombia and the ineptitude of the Spaniards has increased te yearning for independence.

Chapter 46: A Colombian Spring

"Life is much more bitter if visualized through the dark lens that arise from the death of the Indian Luis Chicaiza, executed the 20th day of the present month in the Independence Square of this very city. His life was but constant suffering, his life was but a continuous separation from the most cherished affections of the heart, his life was but a chain of misery, a chain of heavy steel made worse by the weight of the social question of this day"

-Introduction to "The Indian's Plight" by Dolores Veintimilla.

The Federalist controlled Congress had just one objective: to destroy the Diaz administration before it even started. Armas, reelected for a second term, immediately announced that the official Federalist policy should be to “make Mr. Diaz a one term president”, adding that preferably “he shouldn’t last into the next session”. The young Senator Antonio Noboa, from Santafe, supported the motion, stating that “the conservative ideals of careless taxation and spending can only lead our nation to ruin”, thus the Congress had to take the leading role in shaping national policy and correct those mistakes.

“What are the mistakes the Federalists parrot about?”, asked a Conservative Congressman. The mistakes, a widely circulated Federalist pamphlet announced, were the reckless overspending the Cruz administration supposedly undertook and the international loans the state had to take as a result. The hands-on approach to the economy undertaken by Cruz was also constructed as tyrannical violations of states’ rights.

This was a result of commercial interests that had ruled the country since the Colony. Ports such as Guayaquil, Cartagena and Caracas all had their own elites and pursued different commercial paths. Though they accepted a Union for military and political purposes, they weren’t willing to submit to Santafe when it came to trade. As a result, the Federal Government’s ability to regulate the country’s economy was limited to tariffs, which most Federalists wanted to use sparingly. Then came Cruz, whose economic policy was practically a form of State Capitalism, including tariffs to protect and cultivate industry, subsidies to companies and foreign investments.

The economic boom, or bubble, of the Cruz era allowed the growth of several banks. As usual for Colombia there were three main banks, each one dominating its respective district: The Banks of Guayaquil, Cartagena and Caracas. Other important banks included State owned banks such as the Agricultural Bank and British Firms. But the aforementioned three banks dominated the Colombian economy. The biggest one was the bank of Caracas, which made the city the heart of Colombian finance and investment, thanks in big part to Cruz’s favoritism towards the Conservative City.

The Bank of Caracas

The bank of Caracas was by 1850 the biggest investor in Hispaniola’s sugar, and other crops such as tobacco and cotton. This created an economic bubble. The only thing keeping it from bursting was the belief that King Sugar was invincible. This belief was strengthened by the failure to compete of the West Indies and Cuba during the 1840’s. In the West Indies, the abolition of slavery by both the British and the French at roughly the second time and their inability to implement systems of free labor led to a downturn in production and the loss of workforce. While in Cuba there was significant pro-independence agitation due to Spain’s inefficient administration.

This had changed by the beginning of the 1850’s. Spain’s government, driven by an industrializing and progressive desire, started to once again develop Cuba’s sugar, even if a heavy army presence was needed to stop the island from openly rebelling. The West Indies, for their part, started to produce again. Colombia even faced competition from the Southern United States, which prevented the take-off of Colombian cotton and drove down the prices of other commodities. This preoccupied the investors. But this was not the only source of disaffection with Cruz’s policies.

Truth to be told, many simple didn’t like the PCN’s vision of progress. The idea of an industrial Colombia of steal and coal was terrifying, and many preferred their old agricultural nation. The small, provincial towns and free laborers of yesteryear were juxtaposed with the big but soulless cities and the oppressed workers, subjected to wage slavery. This romantic idea of Colonial and Early Republican Colombia might not have been completely true, and many admitted to it, but it offered guidance and a different way of progress than the one the PCN advanced.

“The champion of our motherland’s destiny, the one we will truly bring a new dawn to Colombia is the small farmer, who sows the land and enriches it. Not the corrupt industrialist who steals from the workers, not the industrial pawn”, said the Conservative Federalist Arturo Juarez from Apure. These conflicting visions of Colombia’s future drove a wedge not only between the PCN and the Federalists, but also between Liberal and Conservative Federalists.

Colombia was still a largely agricultural country. Most of the population was still dedicated to the cultivation of either commercial crops such as sugar and coffee or subsistence farming like potatoes and maize. Big landowners still ruled over large swaths of territory. And despite the advance of communications and transport most Colombians were either farmhands in large plantations or small farmers living in small homesteads. Migration to the cities, education and literacy was increasing, but this upwardly-moving middle class was small.

Conservative and Liberal Federalists both opposed the PCN’s idea of progress, but Liberals were willing to borrow some ideas from it. Crash industrialization, that provoked class conflict, riots and wage slavery was wrong, but developing Colombia’s resources and fomenting its industry was not. “Agriculture and industry should advance together, hand in hand”, declared the Federalist editor of the Colombian, a popular newspaper of the Central District. The large landowners who took all the land to themselves and the robber barons who stole the nation’s workforce and minerals were not the Liberal’s vision of the future, but as the 1840’s advanced they started to analyze their views and dream of a Colombia united by railways and telegrams, where everyone had opportunity to improve themselves and advance, and education and industry promoted progress and innovation. In other words, they agreed with the PCN’s new dawn, just looked for other ways of achieving it.

Industrial strike in the Caracas Iron Works.

This was anathema to the Conservative Federalist, who completely rejected this idea of progress. They pointed to the problems of industrialization, not only in Colombia but through the world. The rise of Ecuador’s textile mills and the advancement of railroads had destroyed the little merchants and artisans that once thrived, for an Indigenous household could simply not match the speed and price of a factory, and neither could a Pardo merchant survive when goods from other regions and countries flooded his city. As mentioned previously, riots and discontentment seemed to become almost epidemic through the upstart Republic, because the worker’s wages grew much more slowly that the factory owners’. The advance of industry, factories and the railway were met with resistance and resentment, and many towns withered and died due to being left out of the main communication routes.

These differences threatened to split the Federalists Party, but they managed to find unity in opposing Cruz, and now Diaz. Diaz in certain ways was much more hated than his predecessor. He didn’t carry the status of National Hero Cruz enjoyed, and he was practically the physical representation of the previous administration’s economic policies. He earned more resentment by the Federalists because he largely continued Cruz’s agenda. Then came the crash.

Like many other economic panics, the Colombian Crash of 1851 was a result of several factors, including the reduction of the prices of commodities, economic bubbles as a result of crash industrialization, and internal and external market shake-ups that shook the weak Colombian economy. In this case, the Federal government’s inability to correctly regulate the national currency, the Piastra, eroded confidence on the government’s credit and ability to pay. The large foreign loans Cruz had taken had to be payed with hard currency, but the Pacific War and Medina’s Revolution in Peru disrupted the production of gold from these regions. The State attempted to pay the British investors with Piastras and government bonds, but they rejected the measure, causing a Panic in the Bank of Caracas, which quickly expanded through the country.

The collapse of the Caracas Stock Exchange impacted many industries directly, chiefly the Andean Railway Company, the Colombian Steel Company and the sugar plantations of Hispaniola. The Federalist Congress immediately announced this as the terrible but logical consequence of Cruz and Diaz’s policies, and demanded action from the Federal Government. A plan for adroit action was quickly drafted, but it drew heavy opposition from several sectors of the nation. Diaz plan, deviating from Cruz’s normal policies, proposed a federal bailout of Hispaniola’s plantations, which would allow them to sow and reap during the next producing season. But the main issue remained, how would Colombia pay its foreign debt?

Diaz introduced a bill that eliminated the federal subsidies of several companies and issued budget cuts to education and welfare programs, while also raising taxes and imposing new tariffs. Diaz hoped to please both sides by adopting ideas from both the National Conservatives (taxes and tariffs as revenue sources) and the Federalists (less government interference in the economy, fiscal responsibility). He only managed to alienate both sides. “Cruzistas”, that is, Cruz’s supporters, accused Diaz of taking reckless measures that would cause unrest, unemployment, and the death of Colombian industry, while the Federalists chafed under yet more directives, regulations and taxes from the government. This spark of disaffection finally sparkled the Colombian powder keg of racial and class tensions, as the National Conservative’s predictions came true and unemployment spread through the country.

Quito, with its extensive textile industries and labor force, was especially hit hard by the economic crash. The resulting unemployment of thousands of laborers, many of them indigenous and mestizo, caused riots and social instability, while also emboldening Young Colombians and Federalists who resented the direction the National Conservative city was taking. The Young Colombians started a fight against poverty, bad government and discrimination that culminated in the Chicaiza Affair.

Unemployment in Colombia

Chicaiza, a textile worker of indigenous descent who lost his job following the crash, was accused of murder and robbery. Chicaiza was unable to find support or even hire an attorney, and was predictably condemned to execution by the Criollo court, despite the evidence being less than conclusive. Modern historians agree that Chicaiza was most likely a scapegoat for a crime committed by someone of higher social status. The Affair would most probably have ended there if Chicaiza’s friends and families hadn’t tried to resist his arrest by the Ecuadorian police. This act of rebellion quickly expanded into a riot by poor indigenous people, who denounced the discrimination of the courts and the lack of action by the government. This prompted the Governor of Ecuador, Juan Andres Nueces, to send in the state militia. Scared by the militiamen, the Natives didn’t put up resistance and Chicaiza was taken away.

This made the Young Colombians jump into action. A group of young but talented lawyers of middle-class extraction, called the Quito Five, decided to take up the fight for Chicaiza and appealed the decision. The Court of the Pichincha Department accepted the appeal and a new trial was begun. The new trial, started with only the objective of proving Chicaiza’s innocence, quickly became a social fight, a struggle between the poor and defenseless against the forces of a government that abandoned them. The case drew widespread national attention, as Young Colombians through the country poured resources and support for the Quito Five. But it also exacerbated the divisions between Federalists, for Liberal Federalists openly supported the effort while Conservatives condemned it.

In Guayaquil, the closest major city to Quito, Liberals rallied around the venerable and seemingly eternal Governor Jose Joaquin de Olmedo. Olmedo had been the governor of Guayas State since the Santander Administration, winning every reelection with big margins of victory. Though he planned to retire soon, he was still an active force. During the Santander age, he was the man around whom Federalists who opposed the administration rallied. He, in their view, represented the old and true federalist doctrine of Miranda. But included in Miranda’s ideas were the fight for civil rights, and this ironically made the old conservative Federalist Olmedo the foremost supporter of the Quito Five.

Guayaquil, the most important Colombian port in the Pacific, and after the Pacific War, the most important South American Pacific Port, was a staunchly Federalist city, but the divisions between the party and the large but self-conscious laborer class brewed tensions similar to those of Quito, its traditional rival but also biggest commercial partner. And Olmedo’s support of the Quito Five only increased these tensions, transforming the city into a battleground between Federalist factions and, together with Santafe and Cartagena, a center of Young Colombian agitation.

The Young Colombians were dealt a hit when, in mid-1852, the Court found Chicaiza guilty and ordered the execution carried out. The Quito Five tried to appeal to the Supreme Court of Ecuador, decrying biases and prejudice that impeded a fair trial. But the Supreme Court, possibly influenced by Nueces, denied the request. Undeterred, the Quito Five filed a suit in the Court of Appeals of the Southern District and started to lobby for a presidential pardon, arguing that Governor Nueces had breached the law by using militia to arrest Chicaiza.

This arose several constitutional questions. The Quito Five case was built around the Military Regulations Decree of 1835, signed into law by President Santander. The decree expressly forbade Army troops from acting as law enforcement against Colombian citizens and residents unless martial law had been declared and authorized by Congress. Thus, the foremost question was whether the decree also applied to the State Militias, or more broadly, if Federal Regulations also limited the power of State Governments. The lobbying campaign for a pardon also created another question: could the President pardon state charges? Yes, many lawyers answered, President Cruz after all pardoned many people who joined Flores during the Grand Crisis and all charges were dropped, including charges of treason brought up by the State of Venezuela.

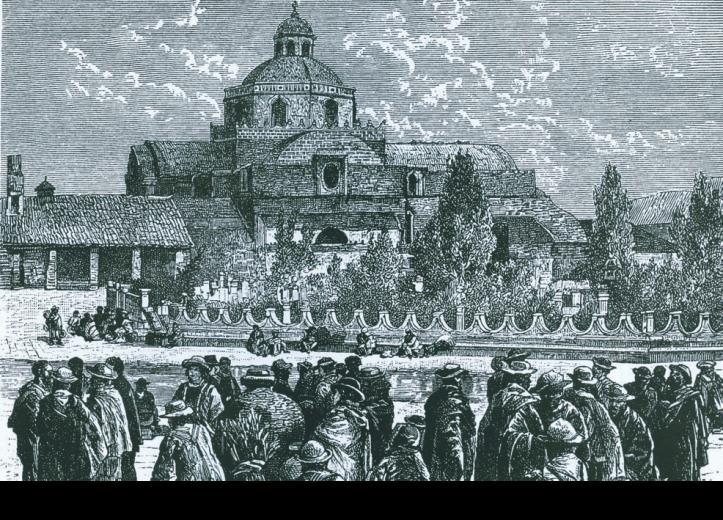

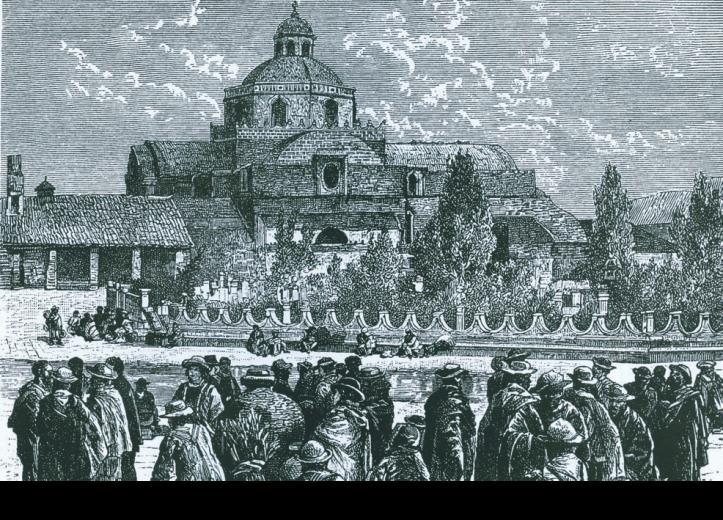

Guayaquil, 1850.

But Diaz and other National Conservatives, more preoccupied with the economic crisis and the Federalists’ attempts to introduce banking and electoral reform, recognized the potential the affair had for weakening their party. The PCN was the party of the Federal Government and Executive Power, but it wasn’t the party of Civil Rights and reform. If Nueces’ actions were declared unconstitutional or Diaz issued a pardon, this would maintain the supremacy of the national government but possibly weaken the party and cause unrest. The contrary would embolden proponents of states’ rights and weaken the executive.

Diaz at the end decided to simply not do anything, and instead he pressured the Court of Appeals to deny the Quito Five’s suit. The Court, staffed by National Conservatives and under the influence of the President, declared that the Quito Five couldn’t file a suit directly without first appealing to the Supreme Court of Ecuador. And since that body had already rejected their appellation, Chicaiza’s sentence would be carried out. Nueces rejoiced, and, willfully interpreting the Court’s lack of statement as permission, he used the militia to arrest Chicaiza and maintain order, upholding the majesty of the law at the price of almost 200,000 piastras while the poor suffered due to lack of welfare.

Chicaiza’s execution was carried out in the Plaza de la Independencia, Quito’s main square. Horrified onlookers and the defeated Quito Five watched as Chicaiza’s chained form was separated from his sobbing family and executed by firing squad. One onlooker, a young Quitean woman named Dolores Veintimilla de Galindo, even fainted.

Veintimilla, abandoned by her husband, a Doctor from Cauca, took solace in writing poetry. The event so shocked her that she wrote her most famous poem, “The Indian’s plight”, a romantic, paternalistic but still compassionate portrait of Native Americans struggles. The poem became famous through the state and then the country, but caused a wave of harassment and pression that ultimately pushed the already depressed Veintimilla to suicide. The Young Colombians were quick to exploit the tragedy for political gain, conscious that the life of a young Criollo woman was worth more to many than that of a poor indigenous laborer.

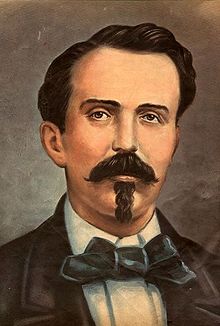

Dolores Veintimilla

Meanwhile, the Diaz administration failed to find a rational economic policy that could get Colombia out of the crisis before it worsened. The National Conservatives decided that giving a Federal bailout to the Bank of Caracas was necessary for a speedily economic recovery, and drafted a bill to that effect. Conservative Federalists opposed it, always distrustful of banks and government interference, but the Liberal Federalists allowed it to pass. When the bipartisan Economic Recovery Decree reached Diaz’s desk, he vetoed it, conscious that the Treasury couldn’t bailout the Bank without taking another loan.

Foreign affairs also influenced Diaz’s domestic decisions. The Mexican American War had started and Colombia had declared itself neutral, but Diaz, continuing the proud Colombian tradition of opportunism, decided to extend Colombian influence in Central America while also offering trade treaties to Mexico. The Castillo government accepted the arms deals by the Colombian Arms Company and also contracted the Andean Railway Company for repairing and keeping the vital Mexico City-Veracruz railway. The Mexican contracts kept both companies above water after the government stopped subsiding them. But the crisis of the Caracas Iron Works and slump in coal production forced the companies to import foreign iron and coal. When the United States embargoed Colombia, the companies’ costs soared until no profit was made.

The US embargo was a result of Colombia’s support of the Mexican war effort and allowing French and Mexican vessels to take refuge in Hispaniola while turning American ships away. Diaz, much to his cabinet and the British ambassador’s chagrin, wanted to cultivate closer relationships with France, something the French emperor Napoleon III welcomed. Diaz hoped that the French banks would provide loans at lower interests, something the British weren’t willing to do anymore. He went even as far as offering use of Colombia’s railways for the transportation of war materiel.

This raised tensions with the US, which finally exploded when the USS Maryland, pursued by French battleships, tried to anchor in Hispaniola. The Colombians refused, sending the ARC Amazonas to stop the ship. The conflict escalated until the Maryland fired on the Amazonas, damaging her. Knowing that backing down would be embarrassing and reduce Colombian prestige and control over other states, Diaz ordered an attack by two other ships, the ARC Magdalena and ARC Orinoco. The three Colombian ships overwhelmed the Maryland and sunk her, killing scores of American sailors.

The diplomatic incident caused the US to threaten war, but it ultimately backed down, mindful that the British might side with Colombia and that, with Ruiz in New Orleans, they had to focus on defeating Mexico. Still, Congress enacted the Embargo Act of 1853, forbidding trade with France, Colombia and “other enemies of the United States”. This Embargo Act proved to be as disastrous as Jefferson’s own, for it dramatically reduced the country’s revenue because it closed or reduced trade with the French block in Europe and the Colombian block in South America. But the American lawmakers could take solace in their success in wrecking the Colombian economy.

The loss of American markets didn’t affect the Colombians at first. Colombia’s top exports were wheat, beef, precious metals and minerals, coal, iron, timber, textiles, sugar, coffee, cacao and banana. The Americans did buy Colombian coffee, cacao and sugar, but the American industry could produce everything else. Colombia’s main markets were South America and Europe. But the loss of American cotton was a heavy hit against Ecuador’s already weakened textile factories.

Social tensions in Quito

The Federalist Congress once again jumped into action, drafting two bills. One, with widespread Federalist support, would encourage cotton production in Magdalena, with premium land sales. The second, only supported by Liberals, would inject money into Ecuador’s textiles. Both bills passed, but while Diaz signed the first into law, he vetoed the second, repeating that the Colombian government had no money for a bailout. To distressed industrialists, Diaz proclaimed that King Sugar would once again save the Republic. But when the sugar crops were sold, the results were disappointing. Despite raising the tariffs by 50%, the Economy Minister reported that less than 60% of last year’s revenue was brought in. This was a result of declining sugar prices and demand. Diaz was forced to yet again bailout Hispaniola’s sugar plantations, which brought further outrage.

It was clear that the Diaz administration had failed to deal with the economic crisis, which emboldened the opposition while alienating his own party. Diaz’s attempts to deal with the crisis on a platform of “fiscal responsibility” made many National Conservatives rage, for the platform was paramount to inaction in their eyes. Diaz’s economic policies basically boiled down to reducing government spending, raising taxes and tariffs and trying to rely in agriculture and trade rather than industry and production. The failure and consequent instability caused many within his party to turn against him, including Cruz, who came back from his retirement to speak against his successor.

The Liberal Federalists introduced a bill that would create a Colombian Central Bank and Federal Reserve. This, they hoped, would restore confidence on the Colombian economy and stop the inflation that had been affecting the Piastra since the crash. The National Conservatives supported the measure, and it passed over Conservative Federalist opposition. Before it reached the president, various PCN Senators and Congressmen met with him in la Casa de Nariño, issuing and ultimatum: either Diaz signed the bill or they would desert him. Diaz called their bluff and vetoed the bill.

The PCN congressmen and senators declared their total opposition to the “incompetent, malicious and stubborn” Diaz administration. They were trying to salvage their party, which looked ready to sink in the next elections. But many had second thoughts about deserting the President, because doing so would fatally wreck his administration and hand power over to the Federalists. This indeed happened, with the Triumvirate of Cali, a group of influential Federalist Senators from Cauca, taking the lead.

Cali, 1850.

The Triumvirate were all conservatives in their third term. This was possible because Cruz had especially excepted the first congress elected under his constitution from his term limits law. Effectively, this meant that the members of that Congress could have up to three terms instead of two. But three wasn’t enough for many of them. The Triumvirate started to lobby Diaz in favor of repeal of term limits and electoral reform. In exchange, they would help him advance his agenda. Diaz, already alienated from his party in Congress, accepted, and when the Federalist majority along with some National Conservatives passed a law amending the Constitution, he signed it into law immediately.

The Electoral Reform Decree of 1853 significantly lowered the economic requisites for voting, expanded the list of “useful industries” that allowed a citizen to vote and abolished term limits. This was as far as the Conservative Federalists were willing to go, which disappointed Liberals and Young Colombians, such as Senator Noboa, who spoke against the bill but still voted in favor of it.

1854 came, and it became apparent that the National Conservatives were going to lose the elections. The President always occupied a much larger part in Colombian politics than in other states, so Diaz’s failures would be translated into heavy losses for the PCN. PCN politicians were especially vulnerable in states such as Ecuador, Zulia, Venezuela, Hispaniola and Azuay, all heavily hit by the crash. In an effort to cut their losses, their National Convention was held in Maracaibo. But the delegates, draw according to Party strength rather than population, deadlocked before they adjourned and tried again in Quito. Another deadlock ensued between anti-Diaz and pro-Diaz delegates until they decided to nominate the governor of Maturin, Cesar Zapatero.

By contrast, the Federalist National Convention was characterized by enthusiasm and action. The delegates quickly nominated Bonifaz again, decided to present a united front that contrasted with the PCN’s divisions. The Convention identified Choco, Apure, Zulia and Panama as battleground states, and Ecuador, Azuay and Maturin as states where they could pick seats.

The election of 1854 was a National Conservative disaster. Bonifaz, aided by the Electoral Reform Decree, swept the Central District while also gaining more votes from the Southern and Eastern Districts than any Federalist since Santander or even Miranda. The Party also picked seats from Ecuador, Azuay and Maturin (the first Federalist congressmen from these states since Miranda), several governorships and many Senate seats, giving them a supermajority in Congress. Whether President Bonifaz would be able to deal with the crisis remained to be seen.

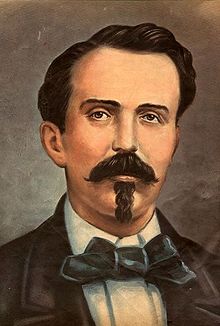

Luis Antonio José Bonifaz de Ortega

The Administration got off to a promising start. Two decrees were quickly signed into law by Bonifaz: The Bank Recuperation Decree that injected money into the Bank of Caracas and the National Trade Decree of 1854, which lowered tariffs and regulations. The Bank of Caracas, saved from the brink of bankruptcy by this bailout, was able to invest in agriculture once again, choosing the safer, but less lucrative options such as tobacco and coffee. The second decree dramatically increased Colombia’s trade, and although the tariffs were at their lowest since Santander, the government’s revenue actually increased due to less evasion, less use of resources for enforcement and, of course, increasing level of trade.

Bonifaz also set up to repair Colombia’s foreign relations. His main goal was to portray a kindler, gentler Colombia, rather than the upstart Republic that meddled in foreign wars and acted as a merchant of death. Bonifaz mediated Central America’s peaceful separation from Mexico, and also went on a goodwill tour, visiting Haiti and attending Princess Isabel coronation as Empress of Brazil. He also successfully negotiated a French loan that funded the Bank of Caracas bailout and put the government on steadier economic ground. Finally, he normalized relations with the USA.

But now that they were in power, the divisions between Federalists increased. The first sign was the confirmation of Bonifaz’s cabinet members. Both wings of the party demanded some of the government’s post, the Economy and Foreign Ministers being the most contested. Compromise was reached at the end, but this did not promise much for the future. When the National Trade Decree reached the President’s desk, it was the result of grueling compromise and hard-fought struggles that produced a “Frankenstein” bill that eliminated only some tariffs while keeping others in vulnerable industries such as iron, textiles and Magdalena cotton. But the need to compromise was not a result of PCN opposition, but Liberal Federalist demands.

This outraged the Conservative Federalists, who accused their fellow party members of being friends of the decadency and unemployment industry caused. The Bank bailout was also their brainchild, which deepened the divisions because the Conservative Federalists opposed banks completely. Finally, the Liberal Federalists prevented the repealing of the Immigration Acts and further budget cuts. The later measure was taken because Liberal ideas had evolved and now they advocated a more active role of the government in economic recovery.

The administration started with wide popular support, but the slow erosion of Federalist party unity prevented further action. Nonetheless, the Colombian economy was recuperating, but common citizens didn’t get that impression, for the factories remained closed or under-manned. Unemployment was still epidemic, and social tensions continued boiling dangerously. Hate against immigrants was on the rise, for the Irish and Spanish small farmers were flourishing thanks to the Trade Decrees while the laborers of the large plantations and industries were still unemployed.

There was still the issue of Colombian foreign debt. Colombia had fallen behind in its interest payments, mostly to British bankers. The Royal Navy decided to flex its muscles as a warming, allowing one of its first ironclads, the HMS Invincible, to parade around Hispaniola. The episode was deeply embarrassing to the Colombian government. A mortified Bonifaz urged Congress to pass a law for balancing the budget. Liberal Federalists, still believing that a Central Bank would be the best option for stabilizing the national currency and economy, passed a bill to that effect instead. At the urging of Conservative Federalists, Bonifaz vetoed the bill, and then issued an Executive Decree raising land taxes.

HMS Invincible

The whole debacle helped to build an image of weakness and indecisiveness around the President. Liberal Federalists especially charged that the Conservative faction of the party was exerting undue influence over him. “The Triumvirate of Cali has become the Triumvirate of Colombia”, according to the sharp-tongued Liberal Federalists Noboa. "The President is just a puppet of vested interests", declare Armas. The Liberal faction also attacked the president over lack of reform. In late 1855, the discontentment over the slow economic recovery and Bonifaz not keeping his promises of reform erupted into an open riot in Santafe, with citizens burning down the Tax offices, Police department and several private homes. They were the worst riots in Colombia since the Caracas riots of 1840.

Bonifaz was paralyzed by fear and shock, and thus the riots continued for almost three days until the Mayor of Santafe sent the militia. Fatalities were relatively low at only 30 people, but the riots served as a cathartic release of ethnic and class tensions. The rioters targeted immigrants, merchants, minorities and government functionaries before the militia put them down in what the Patriot, a Caracas newspaper, called a “city wide brawl”.

The following day another brawl took place in Congress between Conservative Federalists and their Liberal colleges, whom they blamed for the riots. Noboa was especially targeted for his “radical, revolutionary, inflammatory” language. Infamously, the Conservative Federalist Antonio Londoño from Magdalena brandished a revolver and shot the leg of the National Conservative Juan Fernández from Tumbes. When the Honor Guard that protected the Congress stepped in, the Federalist Senator proclaimed that they couldn’t arrest him.

Bonifaz, in an attempt to show his power as President, ordered his seat vacated by Executive Decree and called for new elections. Magdalena’s legislature, dominated by Liberal Federalists, send in one of their own, but the new Senator had to enter Santafe disguised, fearful of attacks by Conservative rioters. Meanwhile, Fernandez resigned his seat to heal from his wound and Tumbes send another National Conservative as replacement. He also had to enter the city incognito, supposedly dressed as a woman. For his part, Noboa escaped the Congressional fight with only a broken nose.

When Congress reconvened under what the Chronicles of Quito called “military occupation by the Honor Guard”, the Conservative Federalists introduced a protest to declare Bonifaz’s Decree unconstitutional and reinstitute Londoño, but it failed due to Liberal Federalist opposition. A smirking Noboa announced to a crowd that order prevailed thanks to Liberal efforts. The same day the Triumvirate of Cali went to his office and they all had a shouting match.

The Santafe rioters perhaps wanted reform, but at the end they didn’t achieve anything concrete. Other people from the city were fighting for reform as well, but they were doing so within a judicial framework. The Quito Five had failed, but their effort inspired and galvanized Young Colombians through the country. By the time Bonifaz was inaugurated, they had become folk heroes, restless fighters that opposed the oligarchs and oppressors that ruled the country, but whose effort was ultimately doomed due to their lack of resources, experiences or support. With Bonifaz’s electoral victory, many hoped to turn the tables in the next judicial case, and when an appeal was filed for the Supreme Court of Ecuador in behalf of Luis Ordoñez, a group stepped forward to take up the fight. That group of experienced and more resourceful lawyers became known as the Santafe Seven.

Sympathetic drawing of Colombia's indigenous peoples.

Ordoñez was, like Chicaiza, an indigenous man, but unlike the hapless textile laborer, Ordoñez was able to assemble a measure of wealth thanks to his relentless work and savvy acquisition of land during Santander’s reforms. A community leader, Ordoñez was also self-educated and a perfect representation of the Liberal ideal of self-improvement and self-made man. Ordoñez had the necessary economic capital for voting, but like many other indigenous men he was disenfranchised. However, Ordoñez challenged this, arguing that the Constitution stated that voting was an unalienable right of any man older than 21 or married with properties valued in 100 piastras. Ordoñez owned land valued in more than 300 piastras.

In Ecuador, most indigenous and immigrants were laborers in plantations. Farming was not considered an “useful industry” and neither was work as a salaried factory worker. Since they didn’t own the land they worked, disenfranchising them was easy. Ordoñez now challenged this by voting in the 1850 election. The Electoral Board of his parish, in the Imbabura department, refused to count his vote, so Ordeñez filed a suit. The suit continued to be appealed until it reached the Supreme Court of the State as Ordoñez v. Ecuador.

The case drew national attention for its potential in regards to enfranchisement and civil rights. The Supreme Court of Colombia was able to review Congress’ and the President’s actions and decrees and declare them unconstitutional or void them. The Court wasn’t as powerful as the US Supreme Court because the Colombian Congress could amend certain Constitutional articles with only ¾ majorities in each chamber (other articles such as the powers and duties of the President and Congress and the rights of the citizens required approval by ¾ of the states as well). Still, the Court was a powerful check. During Santander’s presidency, for example, it approved the constitutionality of his land reforms, crippling the Centralist opposition.

The Santafe Seven took up Ordoñez legal costs and represented him before the Supreme Court of Ecuador. Nueces, still governor of the state, brought his power and influence to bear and the Supreme Court predictably decided against Ordoñez. But this was all part of the Santafe Seven’s strategy, for they wanted to take the case up all the way to the Colombian Supreme Court. The team (which included four lawyers from Santafe, and one each from Guayaquil, Caracas and Medellin) appealed to the Court of Appeals of the Southern District, which accepted to hear the case in early 1855.

The main argument presented by Ordoñez and his legal team was that the Electoral Reform Decree of 1853 enshrined voting as a sacred right of every Colombian man with properties of 50 piastras or salaries of 25 piastras per month, without mention of social status or race. The Decree was federal law, that is, supreme over state law and regulations, and the Constitution empowered and required Congress to protect the rights of the citizens. Since Ordoñez was a citizen, and he fulfilled the requisites, disenfranchising him was illegal and unconstitutional.

Elections in Colombia

The defense argued that Ordoñez’s was disenfranchised following Ecuador’s laws, which set higher requirements for indigenous voters. These laws were not unconstitutional, for the Electoral Reform Decree didn’t expressly forbid discrimination on the basis of race. Consequently, the States could decide on further restrictions.

Liberals and Young Colombians appealed to President Bonifaz, asking for his help in the judicial decision. Conservatives denounced this as illegal and improper. But Bonifaz delivered, and in late 1855 the Court of Appeals decided in favor of Ordoñez and voided the clauses in the Ecuadorian constitution that impeded indigenous voting. Celebrations broke up, especially among Guayaquil workers and laborers. A Zulia newspaper triumphantly announced that two could play the game of “undue political influence”. Ecuador appealed and the case reached the Supreme Court in late 1857.

But the pressure of electoral reform and the judicial case strained Federalist party unity until the breaking point. In 1857, Conservative Federalists introduced a bill that would expressly disenfranchise racial minorities. The leader of the Triumvirate, Jose Marco Solis, plainly stated that Colombia needed to be a nation of “three C’s”: of Criollo, Catholic, Castilian-speaking, men (“Hombres católicos, criollos, que hablen castellano”). Knowing that the Liberals would oppose this, they appealed to the National Conservative third of the Senate. Most of them weren’t willing to be swayed by “vulgar prejudice”, but the promise of cooperation for a stronger Federal government and industry appealed to them. The bill passed after a hard-fought battle in the Senate that threatened to descend into another brawl.

The bill reached the President’s desk along with dozens of petitions and letters. Senators and Congressmen stormed La Casa de Nariño seeking to influence Bonifaz. The most successful was Noboa. He appealed to Bonifaz as a compatriot and colleague, reminding him that they shared a hometown, both being born in Medellin. The sworn enemy of the Triumvirate triumphed and Bonifaz vetoed the bill. The outraged Federalist Conservative caucus of the Senate issued an ultimatum: either the Liberals joined them in overriding the veto or it was the end of the Federalist Party. The Liberals refused and a third of the Senate walked out.

The Federalist Party effectively stopped existing. Many tried to compromise, but the venom and hate between members of the party was too strong. The Liberals embraced their identity and adopted the name of Liberal Party (Partido Liberal), declaring their intention to fight for the rights of the people, to reform the government and create “ethic industry”. Their motto was “farm and industry, hand in hand”. The Conservatives christened themselves as Democrats (Partido Demócrata de Colombia), perhaps unmindful of the irony.

The collapse of his party was a fatal blow for the Bonifaz administration. The President lost both his power to influence legislation and his will to do so. He refused to join either party, officially being an independent for the last year of his presidency. The administration advanced into the following year with “the vigor of a galvanized corpse” according to a Santo Domingo newspaper. No new major economic or foreign policy decisions would be taken, which caused increased discontentment and anger in the light of a still weak economy.

Antonio Noboa

The economic recovery was happening, at last that’s the historic consensus, but the process was grinding and tortuous. The Mexican-American War was over, but the Colombian government had still secured lucrative contracts that allowed the Andean Railway Company, the Caracas Ironworks and the Colombian Steel Company to remain in operation. The Colombo-Peruvian Guano Company was going as strong as ever. But textile and plantation recuperation were still slow, and for the unemployed workers who didn’t enjoy the hindsight of a historian nothing had changed.

Anger increased when the Supreme Court of Colombia announced that a decision would be announced after the election of 1858. This turned the decision into a political issue. Along with the collapse of the Colombian left, the situation seemed poised for a hard-political swing towards the National Conservatives and figures within it that advocated “hard-right” policies. When the three parties walked into their National Conventions in early 1858, they did so knowing that they were about to participate in one of Colombia’s most important elections.

-Introduction to "The Indian's Plight" by Dolores Veintimilla.

The Federalist controlled Congress had just one objective: to destroy the Diaz administration before it even started. Armas, reelected for a second term, immediately announced that the official Federalist policy should be to “make Mr. Diaz a one term president”, adding that preferably “he shouldn’t last into the next session”. The young Senator Antonio Noboa, from Santafe, supported the motion, stating that “the conservative ideals of careless taxation and spending can only lead our nation to ruin”, thus the Congress had to take the leading role in shaping national policy and correct those mistakes.

“What are the mistakes the Federalists parrot about?”, asked a Conservative Congressman. The mistakes, a widely circulated Federalist pamphlet announced, were the reckless overspending the Cruz administration supposedly undertook and the international loans the state had to take as a result. The hands-on approach to the economy undertaken by Cruz was also constructed as tyrannical violations of states’ rights.

This was a result of commercial interests that had ruled the country since the Colony. Ports such as Guayaquil, Cartagena and Caracas all had their own elites and pursued different commercial paths. Though they accepted a Union for military and political purposes, they weren’t willing to submit to Santafe when it came to trade. As a result, the Federal Government’s ability to regulate the country’s economy was limited to tariffs, which most Federalists wanted to use sparingly. Then came Cruz, whose economic policy was practically a form of State Capitalism, including tariffs to protect and cultivate industry, subsidies to companies and foreign investments.

The economic boom, or bubble, of the Cruz era allowed the growth of several banks. As usual for Colombia there were three main banks, each one dominating its respective district: The Banks of Guayaquil, Cartagena and Caracas. Other important banks included State owned banks such as the Agricultural Bank and British Firms. But the aforementioned three banks dominated the Colombian economy. The biggest one was the bank of Caracas, which made the city the heart of Colombian finance and investment, thanks in big part to Cruz’s favoritism towards the Conservative City.

The Bank of Caracas

The bank of Caracas was by 1850 the biggest investor in Hispaniola’s sugar, and other crops such as tobacco and cotton. This created an economic bubble. The only thing keeping it from bursting was the belief that King Sugar was invincible. This belief was strengthened by the failure to compete of the West Indies and Cuba during the 1840’s. In the West Indies, the abolition of slavery by both the British and the French at roughly the second time and their inability to implement systems of free labor led to a downturn in production and the loss of workforce. While in Cuba there was significant pro-independence agitation due to Spain’s inefficient administration.

This had changed by the beginning of the 1850’s. Spain’s government, driven by an industrializing and progressive desire, started to once again develop Cuba’s sugar, even if a heavy army presence was needed to stop the island from openly rebelling. The West Indies, for their part, started to produce again. Colombia even faced competition from the Southern United States, which prevented the take-off of Colombian cotton and drove down the prices of other commodities. This preoccupied the investors. But this was not the only source of disaffection with Cruz’s policies.

Truth to be told, many simple didn’t like the PCN’s vision of progress. The idea of an industrial Colombia of steal and coal was terrifying, and many preferred their old agricultural nation. The small, provincial towns and free laborers of yesteryear were juxtaposed with the big but soulless cities and the oppressed workers, subjected to wage slavery. This romantic idea of Colonial and Early Republican Colombia might not have been completely true, and many admitted to it, but it offered guidance and a different way of progress than the one the PCN advanced.

“The champion of our motherland’s destiny, the one we will truly bring a new dawn to Colombia is the small farmer, who sows the land and enriches it. Not the corrupt industrialist who steals from the workers, not the industrial pawn”, said the Conservative Federalist Arturo Juarez from Apure. These conflicting visions of Colombia’s future drove a wedge not only between the PCN and the Federalists, but also between Liberal and Conservative Federalists.

Colombia was still a largely agricultural country. Most of the population was still dedicated to the cultivation of either commercial crops such as sugar and coffee or subsistence farming like potatoes and maize. Big landowners still ruled over large swaths of territory. And despite the advance of communications and transport most Colombians were either farmhands in large plantations or small farmers living in small homesteads. Migration to the cities, education and literacy was increasing, but this upwardly-moving middle class was small.

Conservative and Liberal Federalists both opposed the PCN’s idea of progress, but Liberals were willing to borrow some ideas from it. Crash industrialization, that provoked class conflict, riots and wage slavery was wrong, but developing Colombia’s resources and fomenting its industry was not. “Agriculture and industry should advance together, hand in hand”, declared the Federalist editor of the Colombian, a popular newspaper of the Central District. The large landowners who took all the land to themselves and the robber barons who stole the nation’s workforce and minerals were not the Liberal’s vision of the future, but as the 1840’s advanced they started to analyze their views and dream of a Colombia united by railways and telegrams, where everyone had opportunity to improve themselves and advance, and education and industry promoted progress and innovation. In other words, they agreed with the PCN’s new dawn, just looked for other ways of achieving it.

Industrial strike in the Caracas Iron Works.

This was anathema to the Conservative Federalist, who completely rejected this idea of progress. They pointed to the problems of industrialization, not only in Colombia but through the world. The rise of Ecuador’s textile mills and the advancement of railroads had destroyed the little merchants and artisans that once thrived, for an Indigenous household could simply not match the speed and price of a factory, and neither could a Pardo merchant survive when goods from other regions and countries flooded his city. As mentioned previously, riots and discontentment seemed to become almost epidemic through the upstart Republic, because the worker’s wages grew much more slowly that the factory owners’. The advance of industry, factories and the railway were met with resistance and resentment, and many towns withered and died due to being left out of the main communication routes.

These differences threatened to split the Federalists Party, but they managed to find unity in opposing Cruz, and now Diaz. Diaz in certain ways was much more hated than his predecessor. He didn’t carry the status of National Hero Cruz enjoyed, and he was practically the physical representation of the previous administration’s economic policies. He earned more resentment by the Federalists because he largely continued Cruz’s agenda. Then came the crash.

Like many other economic panics, the Colombian Crash of 1851 was a result of several factors, including the reduction of the prices of commodities, economic bubbles as a result of crash industrialization, and internal and external market shake-ups that shook the weak Colombian economy. In this case, the Federal government’s inability to correctly regulate the national currency, the Piastra, eroded confidence on the government’s credit and ability to pay. The large foreign loans Cruz had taken had to be payed with hard currency, but the Pacific War and Medina’s Revolution in Peru disrupted the production of gold from these regions. The State attempted to pay the British investors with Piastras and government bonds, but they rejected the measure, causing a Panic in the Bank of Caracas, which quickly expanded through the country.

The collapse of the Caracas Stock Exchange impacted many industries directly, chiefly the Andean Railway Company, the Colombian Steel Company and the sugar plantations of Hispaniola. The Federalist Congress immediately announced this as the terrible but logical consequence of Cruz and Diaz’s policies, and demanded action from the Federal Government. A plan for adroit action was quickly drafted, but it drew heavy opposition from several sectors of the nation. Diaz plan, deviating from Cruz’s normal policies, proposed a federal bailout of Hispaniola’s plantations, which would allow them to sow and reap during the next producing season. But the main issue remained, how would Colombia pay its foreign debt?

Diaz introduced a bill that eliminated the federal subsidies of several companies and issued budget cuts to education and welfare programs, while also raising taxes and imposing new tariffs. Diaz hoped to please both sides by adopting ideas from both the National Conservatives (taxes and tariffs as revenue sources) and the Federalists (less government interference in the economy, fiscal responsibility). He only managed to alienate both sides. “Cruzistas”, that is, Cruz’s supporters, accused Diaz of taking reckless measures that would cause unrest, unemployment, and the death of Colombian industry, while the Federalists chafed under yet more directives, regulations and taxes from the government. This spark of disaffection finally sparkled the Colombian powder keg of racial and class tensions, as the National Conservative’s predictions came true and unemployment spread through the country.

Quito, with its extensive textile industries and labor force, was especially hit hard by the economic crash. The resulting unemployment of thousands of laborers, many of them indigenous and mestizo, caused riots and social instability, while also emboldening Young Colombians and Federalists who resented the direction the National Conservative city was taking. The Young Colombians started a fight against poverty, bad government and discrimination that culminated in the Chicaiza Affair.

Unemployment in Colombia

Chicaiza, a textile worker of indigenous descent who lost his job following the crash, was accused of murder and robbery. Chicaiza was unable to find support or even hire an attorney, and was predictably condemned to execution by the Criollo court, despite the evidence being less than conclusive. Modern historians agree that Chicaiza was most likely a scapegoat for a crime committed by someone of higher social status. The Affair would most probably have ended there if Chicaiza’s friends and families hadn’t tried to resist his arrest by the Ecuadorian police. This act of rebellion quickly expanded into a riot by poor indigenous people, who denounced the discrimination of the courts and the lack of action by the government. This prompted the Governor of Ecuador, Juan Andres Nueces, to send in the state militia. Scared by the militiamen, the Natives didn’t put up resistance and Chicaiza was taken away.

This made the Young Colombians jump into action. A group of young but talented lawyers of middle-class extraction, called the Quito Five, decided to take up the fight for Chicaiza and appealed the decision. The Court of the Pichincha Department accepted the appeal and a new trial was begun. The new trial, started with only the objective of proving Chicaiza’s innocence, quickly became a social fight, a struggle between the poor and defenseless against the forces of a government that abandoned them. The case drew widespread national attention, as Young Colombians through the country poured resources and support for the Quito Five. But it also exacerbated the divisions between Federalists, for Liberal Federalists openly supported the effort while Conservatives condemned it.

In Guayaquil, the closest major city to Quito, Liberals rallied around the venerable and seemingly eternal Governor Jose Joaquin de Olmedo. Olmedo had been the governor of Guayas State since the Santander Administration, winning every reelection with big margins of victory. Though he planned to retire soon, he was still an active force. During the Santander age, he was the man around whom Federalists who opposed the administration rallied. He, in their view, represented the old and true federalist doctrine of Miranda. But included in Miranda’s ideas were the fight for civil rights, and this ironically made the old conservative Federalist Olmedo the foremost supporter of the Quito Five.

Guayaquil, the most important Colombian port in the Pacific, and after the Pacific War, the most important South American Pacific Port, was a staunchly Federalist city, but the divisions between the party and the large but self-conscious laborer class brewed tensions similar to those of Quito, its traditional rival but also biggest commercial partner. And Olmedo’s support of the Quito Five only increased these tensions, transforming the city into a battleground between Federalist factions and, together with Santafe and Cartagena, a center of Young Colombian agitation.

The Young Colombians were dealt a hit when, in mid-1852, the Court found Chicaiza guilty and ordered the execution carried out. The Quito Five tried to appeal to the Supreme Court of Ecuador, decrying biases and prejudice that impeded a fair trial. But the Supreme Court, possibly influenced by Nueces, denied the request. Undeterred, the Quito Five filed a suit in the Court of Appeals of the Southern District and started to lobby for a presidential pardon, arguing that Governor Nueces had breached the law by using militia to arrest Chicaiza.

This arose several constitutional questions. The Quito Five case was built around the Military Regulations Decree of 1835, signed into law by President Santander. The decree expressly forbade Army troops from acting as law enforcement against Colombian citizens and residents unless martial law had been declared and authorized by Congress. Thus, the foremost question was whether the decree also applied to the State Militias, or more broadly, if Federal Regulations also limited the power of State Governments. The lobbying campaign for a pardon also created another question: could the President pardon state charges? Yes, many lawyers answered, President Cruz after all pardoned many people who joined Flores during the Grand Crisis and all charges were dropped, including charges of treason brought up by the State of Venezuela.

Guayaquil, 1850.

But Diaz and other National Conservatives, more preoccupied with the economic crisis and the Federalists’ attempts to introduce banking and electoral reform, recognized the potential the affair had for weakening their party. The PCN was the party of the Federal Government and Executive Power, but it wasn’t the party of Civil Rights and reform. If Nueces’ actions were declared unconstitutional or Diaz issued a pardon, this would maintain the supremacy of the national government but possibly weaken the party and cause unrest. The contrary would embolden proponents of states’ rights and weaken the executive.

Diaz at the end decided to simply not do anything, and instead he pressured the Court of Appeals to deny the Quito Five’s suit. The Court, staffed by National Conservatives and under the influence of the President, declared that the Quito Five couldn’t file a suit directly without first appealing to the Supreme Court of Ecuador. And since that body had already rejected their appellation, Chicaiza’s sentence would be carried out. Nueces rejoiced, and, willfully interpreting the Court’s lack of statement as permission, he used the militia to arrest Chicaiza and maintain order, upholding the majesty of the law at the price of almost 200,000 piastras while the poor suffered due to lack of welfare.

Chicaiza’s execution was carried out in the Plaza de la Independencia, Quito’s main square. Horrified onlookers and the defeated Quito Five watched as Chicaiza’s chained form was separated from his sobbing family and executed by firing squad. One onlooker, a young Quitean woman named Dolores Veintimilla de Galindo, even fainted.

Veintimilla, abandoned by her husband, a Doctor from Cauca, took solace in writing poetry. The event so shocked her that she wrote her most famous poem, “The Indian’s plight”, a romantic, paternalistic but still compassionate portrait of Native Americans struggles. The poem became famous through the state and then the country, but caused a wave of harassment and pression that ultimately pushed the already depressed Veintimilla to suicide. The Young Colombians were quick to exploit the tragedy for political gain, conscious that the life of a young Criollo woman was worth more to many than that of a poor indigenous laborer.

Dolores Veintimilla

Meanwhile, the Diaz administration failed to find a rational economic policy that could get Colombia out of the crisis before it worsened. The National Conservatives decided that giving a Federal bailout to the Bank of Caracas was necessary for a speedily economic recovery, and drafted a bill to that effect. Conservative Federalists opposed it, always distrustful of banks and government interference, but the Liberal Federalists allowed it to pass. When the bipartisan Economic Recovery Decree reached Diaz’s desk, he vetoed it, conscious that the Treasury couldn’t bailout the Bank without taking another loan.

Foreign affairs also influenced Diaz’s domestic decisions. The Mexican American War had started and Colombia had declared itself neutral, but Diaz, continuing the proud Colombian tradition of opportunism, decided to extend Colombian influence in Central America while also offering trade treaties to Mexico. The Castillo government accepted the arms deals by the Colombian Arms Company and also contracted the Andean Railway Company for repairing and keeping the vital Mexico City-Veracruz railway. The Mexican contracts kept both companies above water after the government stopped subsiding them. But the crisis of the Caracas Iron Works and slump in coal production forced the companies to import foreign iron and coal. When the United States embargoed Colombia, the companies’ costs soared until no profit was made.

The US embargo was a result of Colombia’s support of the Mexican war effort and allowing French and Mexican vessels to take refuge in Hispaniola while turning American ships away. Diaz, much to his cabinet and the British ambassador’s chagrin, wanted to cultivate closer relationships with France, something the French emperor Napoleon III welcomed. Diaz hoped that the French banks would provide loans at lower interests, something the British weren’t willing to do anymore. He went even as far as offering use of Colombia’s railways for the transportation of war materiel.

This raised tensions with the US, which finally exploded when the USS Maryland, pursued by French battleships, tried to anchor in Hispaniola. The Colombians refused, sending the ARC Amazonas to stop the ship. The conflict escalated until the Maryland fired on the Amazonas, damaging her. Knowing that backing down would be embarrassing and reduce Colombian prestige and control over other states, Diaz ordered an attack by two other ships, the ARC Magdalena and ARC Orinoco. The three Colombian ships overwhelmed the Maryland and sunk her, killing scores of American sailors.

The diplomatic incident caused the US to threaten war, but it ultimately backed down, mindful that the British might side with Colombia and that, with Ruiz in New Orleans, they had to focus on defeating Mexico. Still, Congress enacted the Embargo Act of 1853, forbidding trade with France, Colombia and “other enemies of the United States”. This Embargo Act proved to be as disastrous as Jefferson’s own, for it dramatically reduced the country’s revenue because it closed or reduced trade with the French block in Europe and the Colombian block in South America. But the American lawmakers could take solace in their success in wrecking the Colombian economy.

The loss of American markets didn’t affect the Colombians at first. Colombia’s top exports were wheat, beef, precious metals and minerals, coal, iron, timber, textiles, sugar, coffee, cacao and banana. The Americans did buy Colombian coffee, cacao and sugar, but the American industry could produce everything else. Colombia’s main markets were South America and Europe. But the loss of American cotton was a heavy hit against Ecuador’s already weakened textile factories.

Social tensions in Quito