Hey I just catched up. This looks alright. I have some questions:

- Is there any chance Cuba and Puerto Rico could revolt in the near future? Yes, they probably will revolt in the future. Tensions are raising and the Spanish haven't been able to keep them down. Cuba and Puerto Rico are basically a mess right now, a combination of daring republicans seeking independence, Colombian opportunists, American filibusters, Mexican men of fortune...

- What’s going on in Bolivia and Paraguay? Not much really. Both are paranoid dictatorships. Bolivar is the one in charge in Paraguay though. That may have some effects in the future.

- What’s going on in Patagonia? Some Chileans are already starting to colonize the area. A Platinean effort is about to start.

- What about the Falk- err, Las Malvinas? They're British. Nobody, not even the Platineans, care about them right now.

- Will Mexico ever gain British Honduras and the Mosquito Coast? Possibly. Colombia controls the other half of Central America, so British interests in the area are secured either way.

- What about Karl Marx? He was butterflied away... or maybe not.

- Would Russia invade Anatolia instead of going to the Mediterranean if it mean not getting the ire of the Brits and French? Most likely. Conquering Tsargrad is a much greater priority in Russia's list than in OTL.

- Would Colombia ever conquer the Philippines? Not now at least. While Colombia has some power projection capacity in the Caribbean due to the Royal Navy and Hispaniola, the Colombian Pacific Fleet is basically a couple of barely floating barges. However, that becomes a possibility once Colombia starts looking to the Pacific.

- What’s the women’s suffrage movement like right now? American women have met as in OTL in a convention and asked for that right. Some European women are waking up too. In Latin America the influence of the Libertadoras such as Manuela Saenz has provoked a push for rights and education for women.

- Are there a lot of Jews immigrating to Latin America? Arabs? There are quite a few Arabs and Jews, especially in Colombia.

- Is there going to be a Congress of the Americas like before? Yes, but the cause is going to be a different one.

- Is Rio Grande del la Sur Spanish or Portuguese-speaking? Portuguese, but there are some Spanish speaking border areas.

- Will Haiti ever join Colombia? The Colombian authorities are gripping with that question as well. The Haitians are seem as uncivilized savages, with a different tongue and history. Haiti is basically a Colombian colony at this point, and due to Colombian influence many Haitians are Spanish speaking now. Still, many within Colombia haven't forgotten the Haitian revolution and are wary of ever recognizing Haiti as a proper part of Colombia.

- How do Mexico and Colombia feel about each other at this point? The relation is cordial. They are not allies, and there have been some tensions in the Caribbean and Central America. Still, Colombia likes Mexico better than the Gringos. As of lately Colombia has been giving Mexico informal support in the war, allowing the French to use Colombian ports and railroads. Buying the cotton Mexico has taken from Louisiana and weaving it into uniforms has netted Colombia a handsome profit as well.

- Will Colombia and Mexico embark on an industrialization program to expand its trade and port capacity since Veracruz’s capture? Veracruz hasn't been captured yet. A brutal fight still ranges there. Most of the port has been destroyed however, and it will have to be rebuilt. That's were industrialization for Mexico comes in.

- What’s going on in Portugal? Portugal is a liberal monarchy in the French sphere.

- What’s going on in India and Southeast Asia? The British have consolidated their Indian holdings. Problems with cotton supply due to the war and bad relationships with the US has led to renewed cotton growing efforts there. Tensions are increasing however.

- When will Colombia build the canal? Yes!

- When will Egypt build the canal? The French are in control in Egypt right now. They will probably try to build it as soon as possible.

- How have you been?

I've been fine, thank you. A little worried with exams and the like. How are you doing?

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Miranda's Dream. ¡Por una Latino América fuerte!.- A Gran Colombia TL

- Thread starter Red_Galiray

- Start date

- Status

- Not open for further replies.

Threadmarks

View all 76 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 62: The Balkan War Chapter 63: The Liberal Revolution Appendix: The Colombian National Army Appendix: The Colombian Cavalry Appendix: The Colombian Artillery Appendix: The Colombian Navy Chapter 64: From the Andes to the Caribbean Chapter 65: The Irrepressible Conflictsnip

I’m doing good. Glad this TL is doing well.

Hi @Red_Galiray I hope you are doing great with your exams. Good to read that Cuba and Puerto Rico (de un pájaro las dos alas, as the song goes...) are to revolt soon, just please, don't make them wait till 1868 as IOTL! Also, how did those Mexican and Colombian adventurers got into the islands? IOTL the Spanish were quite efficent in keeping their last jewels in the Caribean "safe" from insurgent influence for a long time.

Hi @Red_Galiray I hope you are doing great with your exams. Good to read that Cuba and Puerto Rico (de un pájaro las dos alas, as the song goes...) are to revolt soon, just please, don't make them wait till 1868 as IOTL! Also, how did those Mexican and Colombian adventurers got into the islands? IOTL the Spanish were quite efficent in keeping their last jewels in the Caribean "safe" from insurgent influence for a long time.

Thanks! I hope you've been fine as well. The revolt should happen before the Mexican-American War ends, or not long after it at least. The Spanish Inquisi... I mean, authorities are somewhat more incompetent (ASB, I know) mostly because the Independence movements in both islands are much, much more stronger. Colombia and Mexico have been doing great, while Cuba and Puerto Rico have stagnated. As a result, many more people want independence from Spain and have helped Mexicans and Colombians get into the islands.

Chapter 41: The Rape of Louisiana

Finally, by April 1853, the Army of the Mississippi under the command of Lieutenant General Winfield Scott was ready to go up against the Grand Army of the North under Marshal Luis Ruiz.

Butler’s first tentative attack against the forces of Ruiz had almost destroyed the American Army. Though casualties were heavy, this destruction is not in a physical sense. There were enough soldiers to replace those that had died or had been captured, and in fact, Scott’s forces were, for the first time in the war, numerically superior. The major problem was morale.

Scott came back to find depressed and bitter troops. Most of them were new volunteers that had enlisted for three years of service. Even though they had received training, nothing had prepared them for the carnage that the First Battle of the Mississippi was. Almost as many soldiers were incapacitated or killed as the total of the entire Eagles’ Offensive. And at the end, the Americans didn’t accomplish anything. Scott’s men’s morale was on the ground, and their discipline suffered greatly as well. Desertions reached an all-time high while enlistment levels decreased.

Scott’s return brought back some hope to these battered troops. Many cheered and shouted when they heard that Scott, the Grand Man of the Army as he was called, had returned. The old failures of Taylor and Butler would be left behind, and victory would be reached! However, Scott, an experienced commander, knew that defeating the Victor of New Orleans wouldn’t be so easy.

Winfield Scott assumes command of the Army of the Mississippi.

Winfield Scott was born in June 13, 1786, in Virginia. After an unsuccessful attempt to practice law, Scott managed to join the army thanks to his connections with some senators. Scott would spend the next years as a military officer of low rank. He gained his nickname “Old Fuss and Feathers” due to his insistence in proper military discipline and the wellbeing of his men.

Scott first achieved fame during the War of 1814. The disastrous campaigns around the northwest had led to the British taking control of most of Michigan and had allowed them to start an offensive towards New England and New York. The British offensive towards New England was successful. “Burgoyne’s revenge”, as it was called, ended with New England cut from the rest of the United States. However, Scott and another officer, future president William Henry Harrison, managed to stop British General Andrews’ renewed attack towards Boston, and followed this victory with a triumph over Native American forces in Michigan. Tecumseh died during the battle, and though the British retained control until the end of the war and after it, the dream of a Native American confederation died with him.

The British would change their strategy after Andrews’ failure. “Burgoyne’s revenge” gave way to “Clinton’s revenge” – the British led an offensive that captured Washington and finished the war. Neither Scott nor Harrison were able to do much after their only triumph, but it, as one of the few American victories in a disastrous war, was enough to make them into war heroes. Scott and Harrison, together with the prominent Senator Henry Clay, would in later years become the foundation of the Liberal Party, which they characterized as an alternative to the “old, dysfunctional, ineffective” Democratic Party.

Harrison appointed Scott as commander in chief during his term. Scott was a capable commander, and he led the US army to successful campaigns against Native American tribes. Scott didn’t agree personally with the anti-Native American policies enacted by several states, and as an influential Liberal he collaborated with Clay to keep those state policies from becoming federal ones. Scott, as most Liberals, was also opposed to the war, yet he didn’t refuse command because he considered it his duty towards his country and people. Scott’s letters, however, reveal him to have been conflicted, not only because of the moral implications of a self-claimed empire of liberty waging a war of conquest, but also because he didn’t trust the US Army’s capacity to defeat the Mexicans. He had voted against war during President Cass’ “Secret Meeting” some years ago.

Henry Clay.

Scott’s fears materialized soon enough. The United States went from invasor to invaded when Ruiz defeated Taylor at San Jacinto. Ruiz then proceeded to wage a campaign that was described as “the work of a madman” at the time. What made Ruiz stand out from his enemies and several of his allies was his speed and his at times uncanny ability to coordinate with his top lieutenants, Valencia and Noble. “Lighting Ruiz” seemed to be everywhere at once to Taylor, who lamented how he and Ruiz could spare somewhere, and even if Taylor won and Ruiz needed to stop, Ruiz would catch up with him almost immediately.

Ruiz attacked relentlessly and furiously. To ensure his troops remained fresh he divided them in different corps, thus taking advantage of his superior numbers; and to ensure Taylor’s men were tired and unable to mount a defense, he attacked them constantly. To be able to do this even without railroads or support was not only daring, it was stupid from the point of view of many. The Duke of Wellington, who quickly became interested with the war, announced that Ruiz would probably be encircled and destroyed quickly.

Yet Ruiz managed to execute his campaign. Planters and farmers in Louisiana were not friendlier than the Texians, and thus Ruiz had to seize their property to obtain food for his men. So, while Noble and his cavalry harassed Taylor and kept him from protecting his countrymen, Ruiz and Valencia plundered Louisiana. Some Cajuns and poorer farmers were more willing to trade with Ruiz, and that helped as a secondary food source and allowed him to buy munition and arms. Captured Americans also allowed him to give arms to his men. Still, Ruiz sometimes had to settle somewhere and wait for arms supplies before starting attacking again. Practically all of Mexico’s wagons and horses were used to transport these arms, which allowed Ruiz to remain equipped.

The extent of Ruiz plundering has been debated. The Louisiana campaign featured quick, almost constant fighting and thus Ruiz didn’t really bother to put on place systems for accountability. He forbade the looting of goods such as money and robbing poor farmers (“We can’t take something from the man that doesn’t have anything”), but since Ruiz was more preoccupied with destroying Taylor before the Americans could put their greater logistical and industrial capacity to bear, it’s unlikely that those rules were respected.

An American camp by the banks of the Mississippi.

Wellington noted the irony of the Mexicans being well supplied while the Americans were not. Taylor had enormous quantities of food and ammunition, but Ruiz constant harassing and the fluent nature of the Louisiana campaign meant that he couldn’t really resupply. He needed to move faster than his wagons and horses could, which was clearly shown when Noble and his cavalry destroyed almost a month worth of supplies after Taylor tried to venture into an attack. This forced Taylor to either keep great part of his forces in the back guarding his supply lines or to stay in cities and depots. This often brought great problems to him – after Ruiz’s victory at Shreveport, Taylor had to retreat all the way back to Alexandria. Unlike Ruiz who lived off the land, Taylor couldn’t plunder his own country, and he made sure his soldiers didn’t either.

As a result, Lighting Ruiz moved faster than either Taylor or Scott expected, and that, together with other events out of Taylor’s control such as the Irish Army joining the Mexicans, led to Ruiz’s triumph over Taylor and Scott. Scott had to flee to Mississippi to escape destruction; Taylor ended up trapped in New Orleans. When the French defeated the Americans on May 5th, Taylor was faced with a hard choice – he either had to let his men starve, surrender or take food from the civilians. Unwilling to plunder the citizens of his beloved state, Taylor surrendered New Orleans unconditionally.

A year had passed. Scott had spent most of the time studying Ruiz’s earlier campaign and trying to find ways of replicating it and overcoming the weaknesses of his army. He first set off to train them rigorously. He considered the green brigades he received to be “raw and useless”, and poured all his heart and mind into whipping them into shape. Scott was an effective leader, but despite this he wasn’t inspirational. He had a tendency to put his foot in his mouth, a fact which the hostile Polk administration took advantage of. Yet, his obvious knowledge of military matters and concern for his men inspired respect and admiration in them.

Private Andrew Brown of North Carolina wrote to his wife, detailing how General Scott had made him and the boys feel like an army, feel like victory was possible again. As the troops of the Army of the Mississippi marched, drilled and trained under Scott’s command, their confidence in the outcome of the conflict grew, and that can be seen not only in the soldiers’ letter to home, but also in the music. Whereas the soldiers used to sing sad ballads and bitter, ironic tunes, the Army of the Mississippi’s new marching song showed hope and confidence:

The Army of the Mississippi.

By March 1853, Scott was ready to launch his offensive. Marshal Ruiz, was informed of this by a runaway slave. Ruiz wasn’t convinced of his ability to withstand this offensive. Shortly after the First Battle of the Mississippi he had told his aide de camp that, had Scott been in command instead of Butler, they would have had to evacuate. Now, Ruiz was sure that would happen.

Even though Ruiz’s campaign had been praised by figures such as the Duke of Wellington, the fact is that Ruiz had overstrained Mexico’s weak logistics. By his own admission, he wouldn’t have been able to keep up with his previous pace if the St. Patrick’s Brigade hadn’t deflected. Ruiz now didn’t have enough arms or artillery to defend effectively, much less to attack, and he viewed with preoccupation the growth of the Army of the Mississippi to around 80k men, while the Grand Army of the North, due to a combination of reinforcements being desperately needed in Veracruz to difficult logistics, was stuck at around 60k men.

During a time between the surrender of New Orleans and the start of the Veracruz Campaign, Ruiz enjoyed effective supply lines thanks to the French, who send ships loaded with gun power, shells and ammunition. That period ended when Perry assembled the American fleet and led them to their first major victory over the French. Now supplies had to be brought overland again, something easier said than done due to the terrible guerrilla warfare that raged on Texas and Louisiana. This bush war was characterized by murder and destruction, and forced Ruiz, an active commander who felt at his element in a war of movement, into an uncomfortable position where he had to guard supply lines and the countryside.

Ruiz was also uncomfortable in his new position as the leader of occupation forces. During the Louisiana Campaign taking food and moving on had been easy, but now Ruiz had to actually put a system in place to keep his men fed. Louisiana had around half a million inhabitants, 300k of whom including more than 100k in New Orleans (down from 130k before the war) were under Ruiz’s control. To administer Louisiana Ruiz decided to create what he called the Louisiana Military Administration (Administración Militar de Luisiana) or AML. The AML would, in theory, regulate what and how much the Mexican soldiers could take from civilians, control crime, keep the soldiers in line and prevent insurrections. In practice, the AML often fell short of what was needed, but it’s agreed that it did prevent chaos from arising in a war thorn area.

Guerrilla Warfare in Texas and Louisiana.

The principal aim of the AML was getting enough food for the soldiers without starving the native population. Though moral concerns played a part, some cynics have suggested that Ruiz only cared about the possible international backlash. Either way, Ruiz set strict standards that only allowed his soldiers to take food from farmers who could afford it, and that if food was taken from someone, he was exempt from further requisitions. Ruiz’s only allowed his soldiers to take cattle, salted meat, hams, bacon, corn, flour, vegetables and beans; and forbade the taking of money or other valuables. Every time something was taken a receipt had to be given. These receipts, or “Mexican dollars” carried a promise of eventual payment and were issued in Mexican currency, the peso imperial, usually known simply as the Imperial. The Mexican Parliament approved the emission of these receipts, though some MPs from the National Patriotic Party opposed the measure.

However, the receipts suffered from lack of guarantees and backing. Since they were backed by imperials instead of gold, they were prone to devaluation. Furthermore, many times the soldiers ignored Ruiz’s decree and didn’t issue the receipts, just taking what they needed, including valuable goods. To be fair to Ruiz, the few planters who did raise complains against the soldiers were heard, and when soldiers were caught they were disciplined, yet the end result was the same – the stolen goods weren’t returned, instead more receipts were issued.

Making estimates for how much food was taken from the civilians of Louisiana is impossible, due to inaccurate or lost records and the fact that soldiers often took a little extra and didn’t report it. Still, most of the food taken was given to Ruiz, who then gave it to his soldiers and some civilians.

The AML also instituted special system for other goods. The first category, “essential” goods, were completely confiscated. The category included goods such as salt, sugar, vinegar, coffee, tea, extra shoes and clothes, and alcohol. These goods would be rationed – vulnerable people such as women and the elderly would receive rations first, then the soldiers and finally the families of Louisiana. The unintended result was shortages. “Salt is more valuable than gold now” a Mexican private wrote back home. Ruiz took great care to prevent his soldiers from taking any of the goods in the list for themselves. Accounts show that officers were willing to turn the other way if they found gold in the possession of their men, yet if they found salt or sugar they would take them immediately, wary of angering Ruiz.

Food shortages in Louisiana.

The third category were “valuable” goods. This doesn’t refer to gold or gems, but to cotton. By 1850, the South was producing around 2.5 million bales of cotton. Louisiana’s plantations produced a sixth of the US production, sitting at around 800k bales. Though many of the cotton producing areas were still under US control, Ruiz still had abundant plantations within his occupation zone. King Cotton, Southern senators had argued several times, ruled the world, and Ruiz was inclined to agree. By edict he bought all the cotton in the AML. He didn’t use Mexican dollars, but Mexican government bonds, approved by Parliament. However, the price he paid for the cotton was subpart. Cotton prices were at their lowest just before the war’s start but had risen due to increased demand for uniforms and problems of supply thanks to the Second Quasi War. Ruiz paid only pre-war prices, and sometimes not even that. Planters were understandably hesitant to “sell” their cotton, so Ruiz often used coercion and force of arms to take it, sometimes not giving anything in exchange if the planters were especially combative (“especially combative” ranging from armed resistance to light hesitation). Many planters stopped planting cotton after Ruiz took the yield of 1855 and 1856, but this backfired, since by the time of the second yield Ruiz had already left.

Through requisitions and forced purchases Ruiz was able to bring almost 300k bales back to Mexico. That cotton was then sold for a handsome profit to France and especially Colombia and Britain. While France’s control over Egypt helped them through the cotton famine, Britain and Colombia, both nations with big textile sectors, suffered from it. The profits were immense. A pound of cotton sold at around 7 cents before the war but had risen more than threefold to around 25 cents per pound. However, the United States had embargoed Colombia after it refused to close its ports to French and Mexican vessels, and trade with Europe was depressed due to bad relations with Britain and the continual threat of the French navy. As a result, Mexico was able to sell the requisitioned cotton at 30 cents per pound.

The main buyer was Colombia, who couldn’t get cotton from anywhere else due to the embargo. Though cotton growing efforts in New Granada were well underway, that wasn’t enough to cover the demand of Ecuadorian cotton mills. Colombia bought around 100k bales of cotton, the rest being bought by the French or British or used by Mexican textile mills. This yielded an estimated profit of 36 million US dollars. Originally the Castillo government planned to use the money to pay back the planters, yet there were greater economical concerns that forced it to continue to issue bonds. As a result, a peace settlement that included payment of Mexican debts towards American citizens by the US became one of Mexico’s war goals.

As one can imagine the requisition of cotton was one of the most contentious issues of the Mexican occupation of Louisiana. Southern newspapers told horror stories of Mexican soldiers attacking plantations, taking all the cotton, murdering the owners and laying the torch to the rest. “King Luis” (as they dubbed Ruiz) was a murdering tyrant that had be brought to justice. The Black Legend of Marshal Ruiz, deliberately called so to draw parallels to the Spanish Black Legend, argues that these horror stories had more truth than falsehood. Lewis Riley, a wealthy planter, became an American martyr after he was murdered in a requisition gone wrong. Several more accounts of violence and mayhem exist, for example the rape and murder of Margaret Patin, a young woman who was living alone after her husband joined the army. Many of the soldiers who escaped Louisiana with Scott or were captured by the Mexican army, related how they came back to find their houses destroyed and their women and children dead. Taylor himself found his plantation a smoldering ruin.

/Christiana-crpd2100x1400-56a4890b3df78cf77282ddb2.jpg)

Requisitioning of Louisianan cotton.

Ruiz also has his defenders, the supporters of the “White Legend”. They argue that Southern stories cannot be trusted and that the “Rape of Louisiana” was a greatly exaggerated event, if not a complete fabrication. They point to other accounts, such as the one of Howard Laplante, editor of a New Orleans newspaper, who admitted begrudgingly that the streets of New Orleans had never been freer of "cutthroats and petty thieves". Yet it’s doubtful that that newfound security was a result of Ruiz’s direct actions – the consensus is that it was an unintended consequence of the continuous presence of army units, who protected Ruiz’s life against assassination attempts. Rape during the occupation is more hotly debated.

Ruiz never tolerated rape in the army ranks and was known for swiftly executing any soldier who was found committing such acts. When the army was a cohesive unit that traveled together, it was easy to monitor all soldiers. But now that they were spread all over Louisiana, looking for food and cotton or patrolling rivers and cities, monitoring soldiers was difficult if not outright impossible. Further complicating matters was that women were not likely to come to the Marshal if they had been victims of sexual abuse. Doing so would be a mark of dishonor and shame, and thus soldiers knew they could get away with it most of the time.

In a society that considered women pure, almost perfect creatures such as the antebellum South, this kind of abuse was intolerable. “Will you allow the Mexican hordes to violate the fair daughters of the South?” Senator Calhoun asked his fellow South Carolinians. “No!” answered Liberal Representative from Georgia Alexander Stephens, “men from the Mississippi to the Potomac will lead the liberation of our sister state”. Stephens then added with grim fury that men from the Potomac to New England better do the same.

Stopping the rape of Louisiana became the rallying cry of American men, whether from the North or South. Private Thompson from Massachusetts enlisted in the army after reading reports of the occupation. “I never agreed nor will ever agree to the objectives of this war”, he wrote to his girlfriend, “but I can’t stand idle while those savages plunder and violate our sacred country”.

Newspaper ilustration showing two Mexican officers attacking a young lady.

The occupation of Louisiana proved to be a gold mine of propaganda for the Americans. Emperor Agustin II and Prime Minister Castillo were worried about the implications for Mexico and its standing on the international stage. Several MPs were worried as well. Benito Juarez, who would later become one of Mexico’s most important politicians but was back then just a minor representative, demanded an inquiry. The inquiry couldn’t find anything, concluding that Ruiz was not at fault. Many accused it of bias, but the consensus among historians is that it was true – Ruiz was doing everything he could.

The inquiry didn’t ease Castillo’s mind, and much less foreign concerns. A session of the British parliament discussed the “Louisiana situation”, with several MPs showing distaste for the uncivilized acts going on the occupied state. "The continuation of these attacks against the women of the Anglo-Saxon race cannot be tolerated" declared Home Secretary Lord Palmerston. “How can we support a nation that carries off such heinous crimes?” asked the governor of Hispaniola, Antonio Avila. Napoleon III also showed concern for crime in the AML.

Yet it seems that Castillo had overestimated how much damage Louisiana could make to the Mexican cause. Most Latin Americans were quick to dismiss the rape of Louisiana as gringo propaganda. Even if they believed it, most were willing to excuse the Mexicans, saying that Patterson and the Americans were committing far worse crimes in Veracruz. Latin Americans generally identified better with Mestizo, Catholic Mexico than with the Protestant White United States. A sense of shared culture and race with Mexico appeared in Latin America. Every insult towards Mexicans was thus an insult towards Chile, Colombia, La Plata and the rest of Latin America as well. This led to the raise of an “us vs them” mentality, with many powerful men urging cooperation with “our sister nation, with whom we’re joined together by culture and history”, in the words of Chilean ex-president Horacio Luna.

In Britain, popular opinion was not so much pro-Mexico as anti-United States. The US’ warmongering ways had rubbed British politicians the wrong way, especially war threats over the Oregon territory and attempts at economic coercion. Officially relations were cordial, and trade was actually in the rise, with the US buying millions of British guns and ammunition and Britain buying grain in turn. Yet the prevailing public sentiment was against the US. Many were somewhat amused by how the Empire of Liberty was waging a war of conquest. The satiric magazine Punch published a cartoon that showed the US learning the “family trade” of starting imperialists wars. A National Liberal MP denounced the Americans as “warmongering hypocrites”. Prime Minister Roberts commented dryly that the Americans had nobody to blame but themselves for the “Louisiana situation”. Still, Britain was not willing to intervene in the conflict for or against any side, and besides some warmings to the French and Americans, they remained neutral, quietly profiteering from the saltpeter and firearms trade.

Napoleon III trying to convince John Bull that the Louisiana Situation was nothing to worry about.

The French hate towards Americans could only “be compared to the American hate for Catholics”. Some disdain had quickly morphed into an open, virulent hate as reports of American atrocities in Veracruz and attacks against Catholics reached France. Memories of American “ungratefulness” after France helped the US during the Revolutionary War and of the US’ “betrayal” and the First Quasi-War re-emerged. A sense of commonness with Catholic Mexico developed, while Anglo-Saxon Protestant US was seen as the embodiment of everything France was not. Undoubtedly, some of the old hate towards Britain expressed itself in new hate for its former colony.

International reaction to the rape of Louisiana was not as dramatic as many expected. Countries that supported the Mexico or US before it were not swayed, and countries that favored neutrality weren’t concerned enough. However, the US propagandists never expected to sway any country’s opinion. The rape of Louisiana was far more useful to elicit nationalistic responses among the American youth. The occupation of Louisiana inspired fury and indignation among the people of the US. Other AML decrees caused enormous fury as well, but instead of indignation they inspired fear among Southern planters – the ones concerning slavery.

Mexico and Colombia were considered two of the most abolitionist countries in the time period. Many historians have contested the claim, arguing that although both nations were abolitionist, neither did anything beyond abolishing slavery for their afro populations, which were small compared to the US. Still, both nations’ founders were deeply against slavery and abolished it as soon as political conditions allowed it. While most Mexicans probably found slavery to be an evil, most probably were more concerned with other matters. However, as tensions with the United States rose most of Mexican politicians and reporters started to criticize American slavery. The South, the main force behind the war, was most heavily hit by these attacks.

Still, Mexico had allowed the Ducky of Texas to legalize slavery, but not the slave trade, as part of the compromise that prevented war in the 1840’s. But now that war had happened anyway, Mexico gripped with the question of what to do with the Texians and their slaves. Some proposed liberating all slaves immediately, but the Castillo government rejected the measure, afraid of the possible consequences. Castillo knew that the Americans would probably see such an action as a violation of the laws of war and would subsequently demanded economic compensation or for the slaves to be handed back.

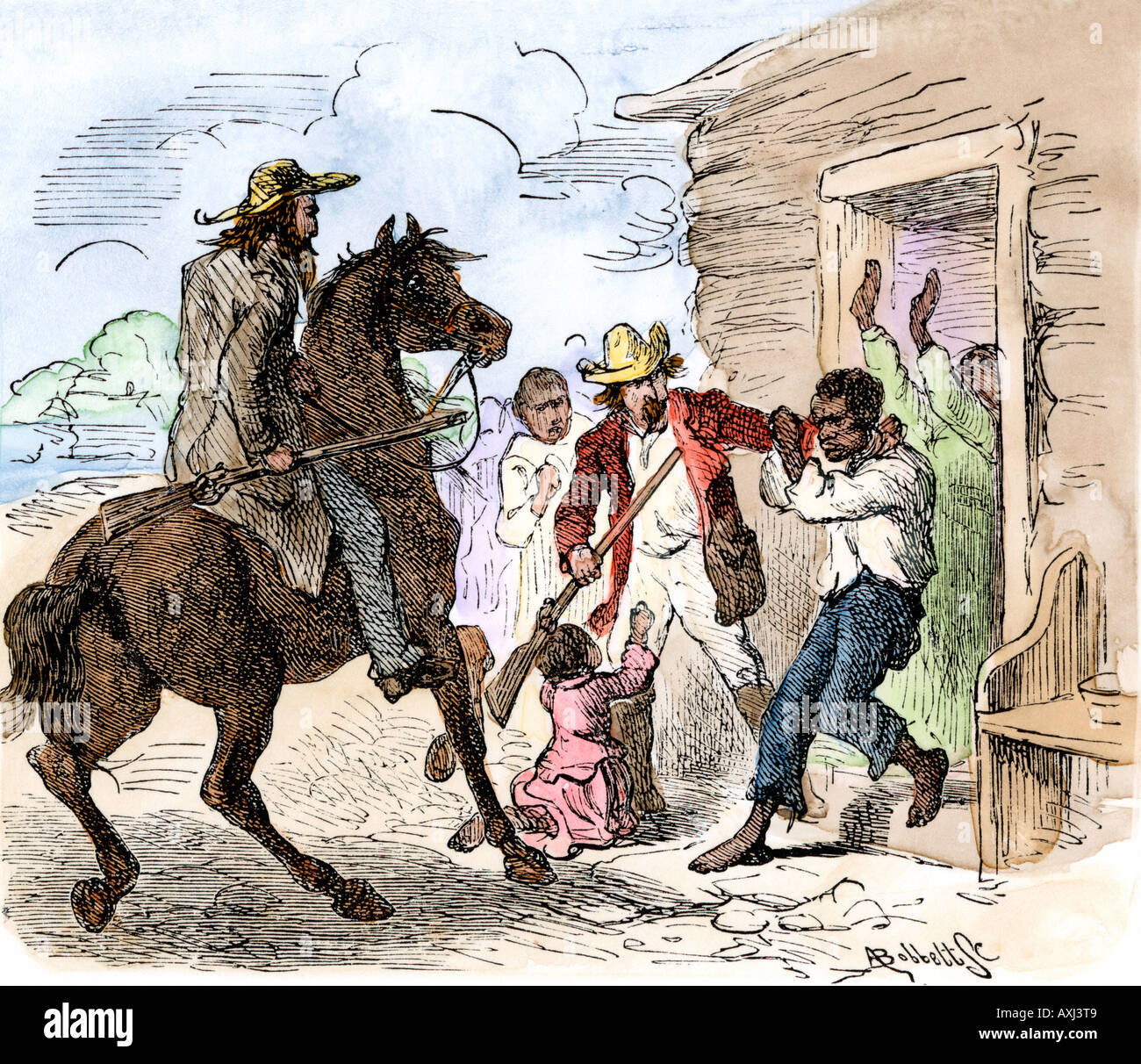

Slavery in Texas.

Thus, instead of total abolition Parliament decided to only liberate the slaves owned by people who had taken up arms against the Mexican government. “If a man uses a rifle in an attempt to undermine a government, international law dictates that that government is well within its rights to confiscate said rifle. The same principle applies here – any slave used unwillingly by his masters in an attack against Mexico must be granted freedom” announced Ernesto García, representative for Sonora from the National Patriotic Party. The García doctrine was applied through the duchy, with dozens or even hundreds of slaves being liberated after their masters took up arms against Mexico. As the conflict moved more and more towards becoming a total war, so did Mexican opinions. Finally, in February 1863 an act of Parliament abolished the Duchy of Texas and decreed liberty of womb and marshal law, as a response to increasingly violent guerrilla warfare. Total abolition was still not decreed because Polk announced that any peace settlement would have to include economic compensation or the return of all slaves.

The situation in Louisiana was more delicate. While the Mexican government could claim authority over the former Duchy since Agustin II was also its Grand Duke, it couldn’t claim any sort of control over Louisiana. The AML had imposed marshal law, and the governor and some local authorities had been replaced by Mexican officers, but most of Louisiana’s constitution and laws remained intact. In fact, many trials were still being conducted by Louisianan courts. As first, Ruiz and his soldiers entered Louisiana with no intention of interfering with the institution of slavery, effectively adopting a “do nothing” policy. Eventually, however, events forced Ruiz to adopt an actual policy.

The first incident happened during the early stages of Ruiz’s campaign. One soldier from a Georgia company had brought his slave with him to army camps. That slave worked cooking meals for his master, but he had happened to overhear the company’s commander talking about Taylor’s next movement. Later that day he managed to escape and reach Ruiz’s lines. Ruiz was going to turn him away at first, until the slave told him what he had learned. Realizing that the information might be useful, Ruiz allowed him to stay. The slave, Samuel, started to work cooking meals for a Tejano Company. He would later settle in Mexico, adopting the surname of the Tejano company’s commander, Gonzales.

Samuel’s fate and the information he gave Ruiz proved to be of little consequence to Mexico or the war, but his escape had a great effect in the administration of Louisiana. Samuel’s owner came to Ruiz’s camp under flag of truce and asked for his slave. Ruiz was at first willing to hand Samuel over, but the Tejano company refused to cooperate. Their closeness to Texian slave owners had turned them into stark abolitionists. Ruiz decided to ask Samuel’s owner for a guarantee that Samuel would not be punished as a compromise. When the slave master refused, Ruiz decided that Samuel could stay with them.

Samuel’s case set a precedent. From that point on many more slaves would try to escape to Mexican lines, expecting to be offered refuge by sympathetic Mexicans. This escalated quickly – soon it wasn’t only slaves brought by soldiers that escaped, but also slaves from plantations in Louisiana and Mississippi. In most cases they did find refuge, being offered work cooking or carrying supplies in Mexican battalions.

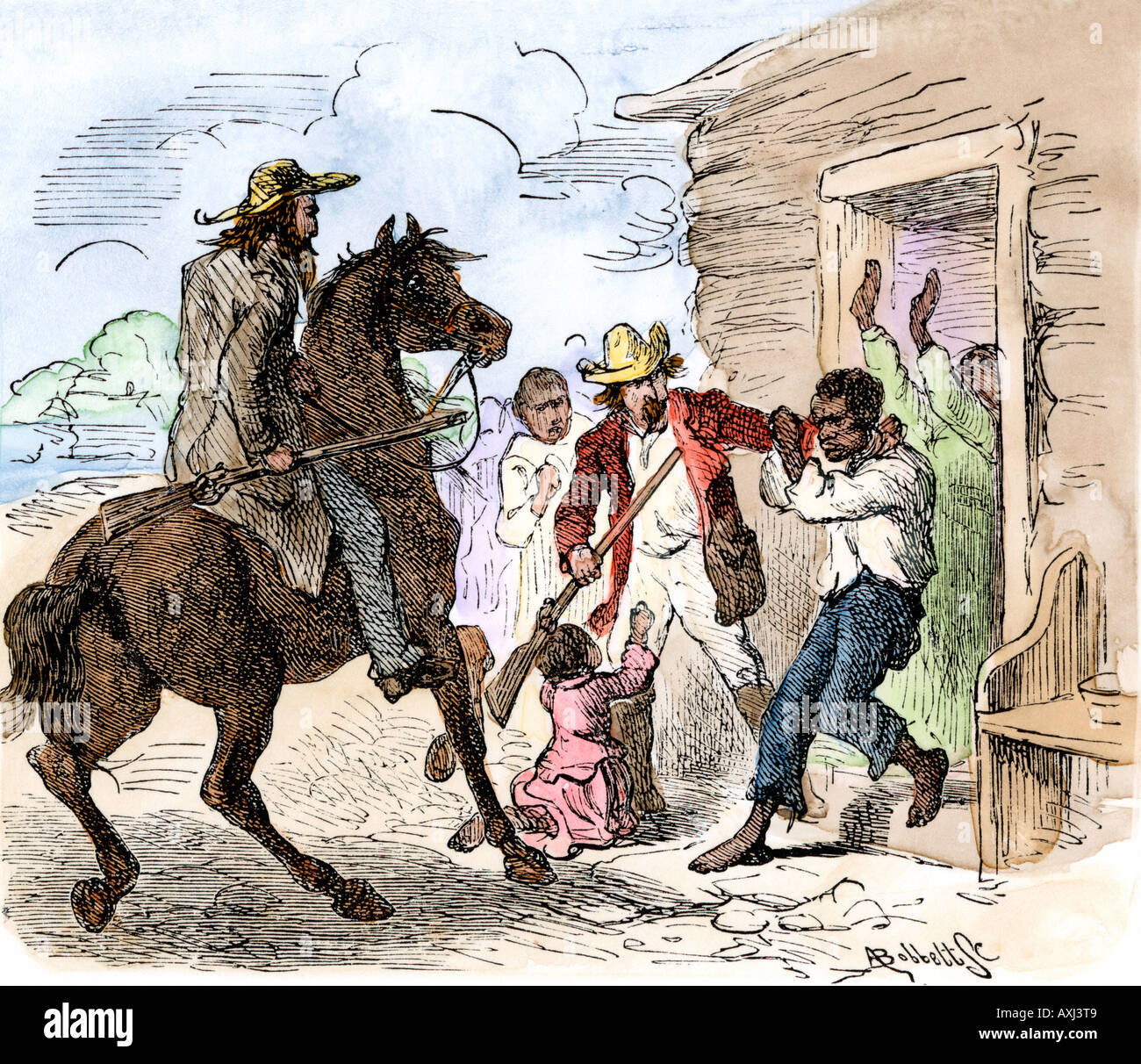

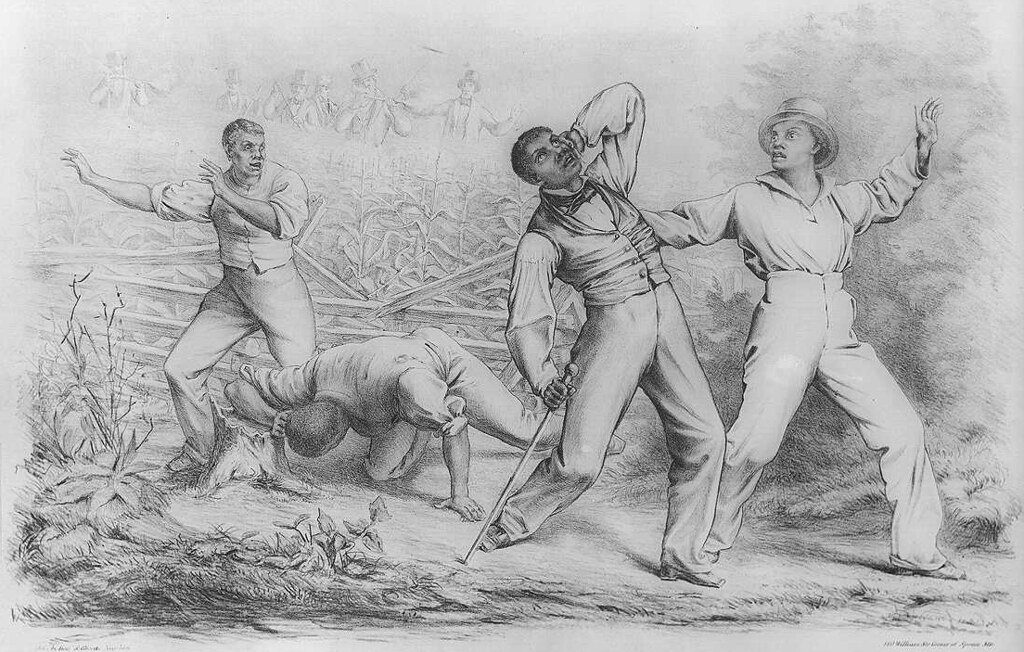

Against his owner's wishes, a slave seeks refuge with Mexican soldiers.

Why those Mexican battalions decided to help the runaway slaves varies. Some did it out of sympathy, others just to spite the gringos, many because the slaves proved useful, helping the troops navigate the terrain and find food. Some Mexican battalions were less friendly, reportedly raping and torturing the runaways (now known as the escapados) but the great majority received them due to practical reasons. Lieutenant Rodriguez from a Sonora Regiment reported that most of his men were able to rest because the escapados were cooking, cleaning and carrying supplies. Other escapados helped the Mexican forces in more substantial ways – mapping the terrain, pointing the location of plantations, serving as spies.

As more and more slaves escaped, tensions rose. From the point of view of Southern planters, the Mexican army was not only the enemy anymore, it was a threat to their society and lives. “The Mexican hordes” warmed Senator Calhoun, “are violating our daughters, murdering our sons, and now are seeking to liberate the Negro and unleash him and his animal lust upon the whole United States.” Jefferson Davis demanded action from Scott and the government, lest “our fair country became another Haiti”.

The most significant incident took place in December 1853. The Carlin affair, or massacre as Southern newspapers labeled it, is a confusing event that started when a Mexican platoon under Lieutenant Cevallos went into the Carlin plantation to get supplies and ended with five men dead, three wounded men, a wounded woman and the plantation a smoldering ruin. There are only two obviously biased accounts: one from Julia Haig, the daughter of plantation and slave owner Horace Carlin, and Cevallos’ own account.

Julia Haig, née Carlin, was a beautiful Southern belle, well known among the New Orleans elite. The daughter of a rich and influential planter, Julia married Charles Haig, a renowned lawyer. They lived together in New Orleans, and when the war started Haig decided to join the army as a lieutenant. Julia stayed behind, writing a diary from the day Haig departed on. Julia’s diary is a great, if biased account of the dread the inhabitants of the city felt while Ruiz and his army approached the city. The last chapters written before Ruiz started to siege New Orleans show almost apocalyptical conditions – rampant crime, poverty, misery, looting, and thousands fleeing one of the USA’s largest cities.

Julia Haig.

After Taylor surrendered the city to Ruiz and the occupation of Louisiana started, Julia decided to heed her father’s pleads and went to his plantation. They lived a peaceful live. Carlin was rich enough to sustain the economical blow of the AML, though Julia’s diary still describes how they were forced to give up their previously lavish lifestyle. A cotton planter, Carlin resisted Mexican attempts to take his cotton and started growing grain and potatoes instead, selling them at New Orleans.

In December, Lieutenant Cevallos and his men arrived at the plantation. Cevallos later claimed during his court martial that the Mexican army had not requisitioned food from Carlin since the occupation started, and that he was only seeking to get “enough” food. This deliberately vague statement conceals half-truths, for one of Carlin’s plantation closer to the frontier had already been sacked, and historians also tend to agree to Julia’s account of soldiers demanding “several pounds of meat and grain, all our salt and sugar, our horses and gold”.

The most accepted reconstruction of the events tells us that Carlin, an old man only accompanied by his thirty slaves, an overseer, some seven men, and his daughter, acquiesced to the Mexican demands and handed over twenty pounds of salted meat, fifty pounds of grain, and payed 500 hundred dollars to Cevallos’ platoon. Julia expressed his dismay at this, believing it to be their ruin. Yet, the Mexican soldiers weren’t satisfied, because they had heard rumors of Carlin’s riches, and demanded more.

This is where the two accounts start to wildly differ from each other, and where obvious bias makes an accurate reconstruction impossible. Though Cevallos would later confess that his soldiers did demand gold (while claiming innocence at the same time), he also claimed that after Carlin told them that he had nothing else they left, but then Carlin’s slave cook, named Thomas, ran to them and asked to go with them. Since their division had no experienced cook, the Mexicans accepted. However, the overseer and Carlin both opposed this violently, declaring it “an outrageous insult to the honor and safety of the United States”. The Mexican soldiers then tried to leave together with Thomas, but the overseer attacked him, trying to murder him rather than leave him escape.

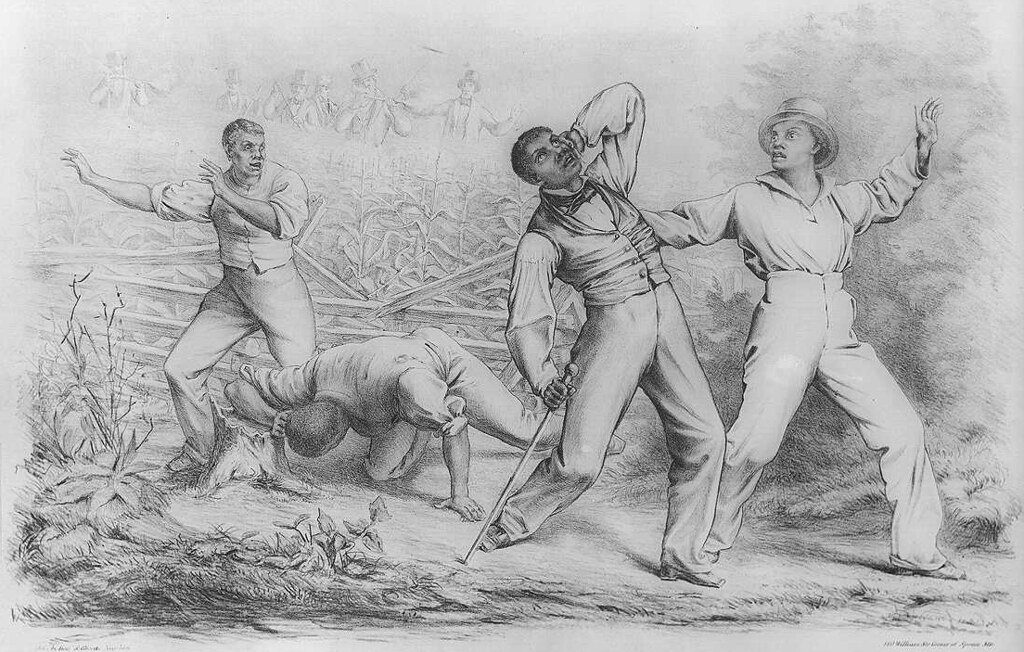

The overseer attacking Thomas.

A fight ensued between Cevallos’ ten soldiers and Carlin and his seven employees. The better armed and trained Mexicans predictably came out in top at the end, losing only one soldier while four of Carlin’s employees died. However, a lamp was knocked into the cellar during the fight, starting a fire that expanded into the Carlin manor. Cevallos and his men, including the wounded Thomas, fled, leaving behind a burning plantation, an agonizing Carlin, and most importantly for those who have contested Cevallos’ version then and now, a wounded Julia. When asked how Julia was wounded, Cevallos could only answer that she probably got to close to the fighting men.

Julia’s account is dramatically different. Most historians agree that Cevallos, who was being court martialed when he related his account, had more of an interest in portraying himself and his men in a positive light, while Julia wrote her version as copying mechanism after a traumatic experience, not as a means of becoming an American heroine. This didn’t keep the US, especially the South, from doing just that. Julia’s original version may be the least biased version of the Carlin affair, but identifying this original version proved to not be an easy task – American, French, Mexican, and even British editors frequently modified the account to suit their interests.

According to Julia, who was hiding in another room when Cevallos and his men showed up, the Mexican soldiers did leave after Carlin swore that he had no more money, but only after “considerable” violence. However, Thomas appeared suddenly and told Cevallos and his men that Carlin was lying, that there were more valuable objects in the house. The soldier’s lust for gold and their anger rose – they assaulted Carlin and the slave overseer, leaving then agonizing on the floor. Thomas then murdered the overseer with a Mexican bayonet, before leading the soldiers to the next room, where Julia was hiding.

The murder of the overseer has been disputed. One of Carlin’s overseer was found death due to bayonet wounds, but due to the state of medicine during the time period it was impossible to know when he died. The shadows around which Thomas’ character is surrounded make and question ever murkier, for Thomas was either a lustful, vengeful, ungrateful Negro or a poor man, a victim of slavery’s horrors, depending on the country.

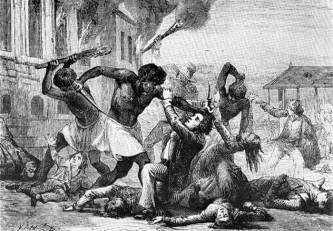

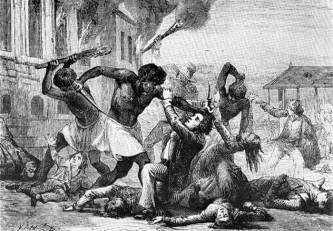

Slaves join the fight in Carlin Manor.

Julia was found by the Mexican soldiers, who tried to rape her, but then the rest of Carlin’s employees arrived. Southern newspaper lionized these employees as martyrs who died defending Julia’s sacred purity again the joined assault of the Negro and the Mexican. But alas, those southern heroes were no match for the soldiers, who massacred them. Nonetheless, they did afford enough time to a wounded Julia, who, fearful of other slaves who were converging in the house, fled with her father southward to New Orleans. Failing to find either Julia or Carlin’s alleged riches, Cevallos and his men lay torch to the plantation and went their way.

Julia and Carlin reached New Orleans after an exhausting night in horseback. The sudden appearance of such a prominent citizen and his daughter in such a state raised panic through the city, so much in fact that Marshal Ruiz himself got wind of the situation. Like everything else in the Carlin affair, deducing what’s truth and fiction about Ruiz’s reaction is hard, but he did provide for the Carlins treatment and wellbeing, and called Cevallos and his men before a military tribunal. Cevallos’ version of the story was accepted as the only truth in the Mexican army, but his men were discharged and Cevallos himself exiled to California. Like all other of “King Luis’” actions, this wasn’t enough to placate the US.

The Carlin affair embodied Southern hatreds and fears. The attack on a fellow planter and one of Louisiana’s fair daughters inspired anger, while Thomas’ participation raised fears about slave rebellions. “The Carlin Massacre” became the symbol of the Rape of Louisiana. The shy and reserved Julia suddenly became the representation of what the US was fighting for (aside from conquest). Guerrillas stepped their game up, and massacres of Tejanos, escapados and free blacks by Texians became commonplace.

Prominent politicians such as Calhoun, Stephens, and President Polk called for immediate action, while Ruiz and his military police organized brutal crackdowns and executions of guerrillas. In New Orleans murder of those who didn’t do “enough” against the Mexicans increased, including appalling cases of torture of some who had been forced to work for Ruiz making shells or clothes. Violence continued to increase as the Rape of Louisiana covered the state in blood.

Butler’s first tentative attack against the forces of Ruiz had almost destroyed the American Army. Though casualties were heavy, this destruction is not in a physical sense. There were enough soldiers to replace those that had died or had been captured, and in fact, Scott’s forces were, for the first time in the war, numerically superior. The major problem was morale.

Scott came back to find depressed and bitter troops. Most of them were new volunteers that had enlisted for three years of service. Even though they had received training, nothing had prepared them for the carnage that the First Battle of the Mississippi was. Almost as many soldiers were incapacitated or killed as the total of the entire Eagles’ Offensive. And at the end, the Americans didn’t accomplish anything. Scott’s men’s morale was on the ground, and their discipline suffered greatly as well. Desertions reached an all-time high while enlistment levels decreased.

Scott’s return brought back some hope to these battered troops. Many cheered and shouted when they heard that Scott, the Grand Man of the Army as he was called, had returned. The old failures of Taylor and Butler would be left behind, and victory would be reached! However, Scott, an experienced commander, knew that defeating the Victor of New Orleans wouldn’t be so easy.

Winfield Scott assumes command of the Army of the Mississippi.

Winfield Scott was born in June 13, 1786, in Virginia. After an unsuccessful attempt to practice law, Scott managed to join the army thanks to his connections with some senators. Scott would spend the next years as a military officer of low rank. He gained his nickname “Old Fuss and Feathers” due to his insistence in proper military discipline and the wellbeing of his men.

Scott first achieved fame during the War of 1814. The disastrous campaigns around the northwest had led to the British taking control of most of Michigan and had allowed them to start an offensive towards New England and New York. The British offensive towards New England was successful. “Burgoyne’s revenge”, as it was called, ended with New England cut from the rest of the United States. However, Scott and another officer, future president William Henry Harrison, managed to stop British General Andrews’ renewed attack towards Boston, and followed this victory with a triumph over Native American forces in Michigan. Tecumseh died during the battle, and though the British retained control until the end of the war and after it, the dream of a Native American confederation died with him.

The British would change their strategy after Andrews’ failure. “Burgoyne’s revenge” gave way to “Clinton’s revenge” – the British led an offensive that captured Washington and finished the war. Neither Scott nor Harrison were able to do much after their only triumph, but it, as one of the few American victories in a disastrous war, was enough to make them into war heroes. Scott and Harrison, together with the prominent Senator Henry Clay, would in later years become the foundation of the Liberal Party, which they characterized as an alternative to the “old, dysfunctional, ineffective” Democratic Party.

Harrison appointed Scott as commander in chief during his term. Scott was a capable commander, and he led the US army to successful campaigns against Native American tribes. Scott didn’t agree personally with the anti-Native American policies enacted by several states, and as an influential Liberal he collaborated with Clay to keep those state policies from becoming federal ones. Scott, as most Liberals, was also opposed to the war, yet he didn’t refuse command because he considered it his duty towards his country and people. Scott’s letters, however, reveal him to have been conflicted, not only because of the moral implications of a self-claimed empire of liberty waging a war of conquest, but also because he didn’t trust the US Army’s capacity to defeat the Mexicans. He had voted against war during President Cass’ “Secret Meeting” some years ago.

Henry Clay.

Scott’s fears materialized soon enough. The United States went from invasor to invaded when Ruiz defeated Taylor at San Jacinto. Ruiz then proceeded to wage a campaign that was described as “the work of a madman” at the time. What made Ruiz stand out from his enemies and several of his allies was his speed and his at times uncanny ability to coordinate with his top lieutenants, Valencia and Noble. “Lighting Ruiz” seemed to be everywhere at once to Taylor, who lamented how he and Ruiz could spare somewhere, and even if Taylor won and Ruiz needed to stop, Ruiz would catch up with him almost immediately.

Ruiz attacked relentlessly and furiously. To ensure his troops remained fresh he divided them in different corps, thus taking advantage of his superior numbers; and to ensure Taylor’s men were tired and unable to mount a defense, he attacked them constantly. To be able to do this even without railroads or support was not only daring, it was stupid from the point of view of many. The Duke of Wellington, who quickly became interested with the war, announced that Ruiz would probably be encircled and destroyed quickly.

Yet Ruiz managed to execute his campaign. Planters and farmers in Louisiana were not friendlier than the Texians, and thus Ruiz had to seize their property to obtain food for his men. So, while Noble and his cavalry harassed Taylor and kept him from protecting his countrymen, Ruiz and Valencia plundered Louisiana. Some Cajuns and poorer farmers were more willing to trade with Ruiz, and that helped as a secondary food source and allowed him to buy munition and arms. Captured Americans also allowed him to give arms to his men. Still, Ruiz sometimes had to settle somewhere and wait for arms supplies before starting attacking again. Practically all of Mexico’s wagons and horses were used to transport these arms, which allowed Ruiz to remain equipped.

The extent of Ruiz plundering has been debated. The Louisiana campaign featured quick, almost constant fighting and thus Ruiz didn’t really bother to put on place systems for accountability. He forbade the looting of goods such as money and robbing poor farmers (“We can’t take something from the man that doesn’t have anything”), but since Ruiz was more preoccupied with destroying Taylor before the Americans could put their greater logistical and industrial capacity to bear, it’s unlikely that those rules were respected.

An American camp by the banks of the Mississippi.

Wellington noted the irony of the Mexicans being well supplied while the Americans were not. Taylor had enormous quantities of food and ammunition, but Ruiz constant harassing and the fluent nature of the Louisiana campaign meant that he couldn’t really resupply. He needed to move faster than his wagons and horses could, which was clearly shown when Noble and his cavalry destroyed almost a month worth of supplies after Taylor tried to venture into an attack. This forced Taylor to either keep great part of his forces in the back guarding his supply lines or to stay in cities and depots. This often brought great problems to him – after Ruiz’s victory at Shreveport, Taylor had to retreat all the way back to Alexandria. Unlike Ruiz who lived off the land, Taylor couldn’t plunder his own country, and he made sure his soldiers didn’t either.

As a result, Lighting Ruiz moved faster than either Taylor or Scott expected, and that, together with other events out of Taylor’s control such as the Irish Army joining the Mexicans, led to Ruiz’s triumph over Taylor and Scott. Scott had to flee to Mississippi to escape destruction; Taylor ended up trapped in New Orleans. When the French defeated the Americans on May 5th, Taylor was faced with a hard choice – he either had to let his men starve, surrender or take food from the civilians. Unwilling to plunder the citizens of his beloved state, Taylor surrendered New Orleans unconditionally.

A year had passed. Scott had spent most of the time studying Ruiz’s earlier campaign and trying to find ways of replicating it and overcoming the weaknesses of his army. He first set off to train them rigorously. He considered the green brigades he received to be “raw and useless”, and poured all his heart and mind into whipping them into shape. Scott was an effective leader, but despite this he wasn’t inspirational. He had a tendency to put his foot in his mouth, a fact which the hostile Polk administration took advantage of. Yet, his obvious knowledge of military matters and concern for his men inspired respect and admiration in them.

Private Andrew Brown of North Carolina wrote to his wife, detailing how General Scott had made him and the boys feel like an army, feel like victory was possible again. As the troops of the Army of the Mississippi marched, drilled and trained under Scott’s command, their confidence in the outcome of the conflict grew, and that can be seen not only in the soldiers’ letter to home, but also in the music. Whereas the soldiers used to sing sad ballads and bitter, ironic tunes, the Army of the Mississippi’s new marching song showed hope and confidence:

Chorus

Marching along, we’re marching along!

Gird on the armor and be marching along!

The Grand Man of the Army, the gallant Scott

He’ll lead us to victory for country and for God!

The Army is gathering from near and from far

The trumpet is sounding the call for the war

Scott is our leader, he's gallant and strong

For God and our country we're marching along!

Chorus

The foe is before us in battle array,

But let us not waver or turn from the way

The Lord is our strength and the Union’s our song

With courage and faith we’re marching along!

Chorus

We sigh for our country, we mourn for our dead

For them to the last drop of our blood we will shed

Our cause is the right one, our foe’s in the wrong

Then gladly we’ll sing as we’re marching along!

Chorus

Marching along, we’re marching along!

Gird on the armor and be marching along!

The Grand Man of the Army, the gallant Scott

He’ll lead us to victory for country and for God!

The Army is gathering from near and from far

The trumpet is sounding the call for the war

Scott is our leader, he's gallant and strong

For God and our country we're marching along!

Chorus

The foe is before us in battle array,

But let us not waver or turn from the way

The Lord is our strength and the Union’s our song

With courage and faith we’re marching along!

Chorus

We sigh for our country, we mourn for our dead

For them to the last drop of our blood we will shed

Our cause is the right one, our foe’s in the wrong

Then gladly we’ll sing as we’re marching along!

Chorus

The Army of the Mississippi.

By March 1853, Scott was ready to launch his offensive. Marshal Ruiz, was informed of this by a runaway slave. Ruiz wasn’t convinced of his ability to withstand this offensive. Shortly after the First Battle of the Mississippi he had told his aide de camp that, had Scott been in command instead of Butler, they would have had to evacuate. Now, Ruiz was sure that would happen.

Even though Ruiz’s campaign had been praised by figures such as the Duke of Wellington, the fact is that Ruiz had overstrained Mexico’s weak logistics. By his own admission, he wouldn’t have been able to keep up with his previous pace if the St. Patrick’s Brigade hadn’t deflected. Ruiz now didn’t have enough arms or artillery to defend effectively, much less to attack, and he viewed with preoccupation the growth of the Army of the Mississippi to around 80k men, while the Grand Army of the North, due to a combination of reinforcements being desperately needed in Veracruz to difficult logistics, was stuck at around 60k men.

During a time between the surrender of New Orleans and the start of the Veracruz Campaign, Ruiz enjoyed effective supply lines thanks to the French, who send ships loaded with gun power, shells and ammunition. That period ended when Perry assembled the American fleet and led them to their first major victory over the French. Now supplies had to be brought overland again, something easier said than done due to the terrible guerrilla warfare that raged on Texas and Louisiana. This bush war was characterized by murder and destruction, and forced Ruiz, an active commander who felt at his element in a war of movement, into an uncomfortable position where he had to guard supply lines and the countryside.

Ruiz was also uncomfortable in his new position as the leader of occupation forces. During the Louisiana Campaign taking food and moving on had been easy, but now Ruiz had to actually put a system in place to keep his men fed. Louisiana had around half a million inhabitants, 300k of whom including more than 100k in New Orleans (down from 130k before the war) were under Ruiz’s control. To administer Louisiana Ruiz decided to create what he called the Louisiana Military Administration (Administración Militar de Luisiana) or AML. The AML would, in theory, regulate what and how much the Mexican soldiers could take from civilians, control crime, keep the soldiers in line and prevent insurrections. In practice, the AML often fell short of what was needed, but it’s agreed that it did prevent chaos from arising in a war thorn area.

Guerrilla Warfare in Texas and Louisiana.

The principal aim of the AML was getting enough food for the soldiers without starving the native population. Though moral concerns played a part, some cynics have suggested that Ruiz only cared about the possible international backlash. Either way, Ruiz set strict standards that only allowed his soldiers to take food from farmers who could afford it, and that if food was taken from someone, he was exempt from further requisitions. Ruiz’s only allowed his soldiers to take cattle, salted meat, hams, bacon, corn, flour, vegetables and beans; and forbade the taking of money or other valuables. Every time something was taken a receipt had to be given. These receipts, or “Mexican dollars” carried a promise of eventual payment and were issued in Mexican currency, the peso imperial, usually known simply as the Imperial. The Mexican Parliament approved the emission of these receipts, though some MPs from the National Patriotic Party opposed the measure.

However, the receipts suffered from lack of guarantees and backing. Since they were backed by imperials instead of gold, they were prone to devaluation. Furthermore, many times the soldiers ignored Ruiz’s decree and didn’t issue the receipts, just taking what they needed, including valuable goods. To be fair to Ruiz, the few planters who did raise complains against the soldiers were heard, and when soldiers were caught they were disciplined, yet the end result was the same – the stolen goods weren’t returned, instead more receipts were issued.

Making estimates for how much food was taken from the civilians of Louisiana is impossible, due to inaccurate or lost records and the fact that soldiers often took a little extra and didn’t report it. Still, most of the food taken was given to Ruiz, who then gave it to his soldiers and some civilians.

The AML also instituted special system for other goods. The first category, “essential” goods, were completely confiscated. The category included goods such as salt, sugar, vinegar, coffee, tea, extra shoes and clothes, and alcohol. These goods would be rationed – vulnerable people such as women and the elderly would receive rations first, then the soldiers and finally the families of Louisiana. The unintended result was shortages. “Salt is more valuable than gold now” a Mexican private wrote back home. Ruiz took great care to prevent his soldiers from taking any of the goods in the list for themselves. Accounts show that officers were willing to turn the other way if they found gold in the possession of their men, yet if they found salt or sugar they would take them immediately, wary of angering Ruiz.

Food shortages in Louisiana.

The third category were “valuable” goods. This doesn’t refer to gold or gems, but to cotton. By 1850, the South was producing around 2.5 million bales of cotton. Louisiana’s plantations produced a sixth of the US production, sitting at around 800k bales. Though many of the cotton producing areas were still under US control, Ruiz still had abundant plantations within his occupation zone. King Cotton, Southern senators had argued several times, ruled the world, and Ruiz was inclined to agree. By edict he bought all the cotton in the AML. He didn’t use Mexican dollars, but Mexican government bonds, approved by Parliament. However, the price he paid for the cotton was subpart. Cotton prices were at their lowest just before the war’s start but had risen due to increased demand for uniforms and problems of supply thanks to the Second Quasi War. Ruiz paid only pre-war prices, and sometimes not even that. Planters were understandably hesitant to “sell” their cotton, so Ruiz often used coercion and force of arms to take it, sometimes not giving anything in exchange if the planters were especially combative (“especially combative” ranging from armed resistance to light hesitation). Many planters stopped planting cotton after Ruiz took the yield of 1855 and 1856, but this backfired, since by the time of the second yield Ruiz had already left.

Through requisitions and forced purchases Ruiz was able to bring almost 300k bales back to Mexico. That cotton was then sold for a handsome profit to France and especially Colombia and Britain. While France’s control over Egypt helped them through the cotton famine, Britain and Colombia, both nations with big textile sectors, suffered from it. The profits were immense. A pound of cotton sold at around 7 cents before the war but had risen more than threefold to around 25 cents per pound. However, the United States had embargoed Colombia after it refused to close its ports to French and Mexican vessels, and trade with Europe was depressed due to bad relations with Britain and the continual threat of the French navy. As a result, Mexico was able to sell the requisitioned cotton at 30 cents per pound.

The main buyer was Colombia, who couldn’t get cotton from anywhere else due to the embargo. Though cotton growing efforts in New Granada were well underway, that wasn’t enough to cover the demand of Ecuadorian cotton mills. Colombia bought around 100k bales of cotton, the rest being bought by the French or British or used by Mexican textile mills. This yielded an estimated profit of 36 million US dollars. Originally the Castillo government planned to use the money to pay back the planters, yet there were greater economical concerns that forced it to continue to issue bonds. As a result, a peace settlement that included payment of Mexican debts towards American citizens by the US became one of Mexico’s war goals.

As one can imagine the requisition of cotton was one of the most contentious issues of the Mexican occupation of Louisiana. Southern newspapers told horror stories of Mexican soldiers attacking plantations, taking all the cotton, murdering the owners and laying the torch to the rest. “King Luis” (as they dubbed Ruiz) was a murdering tyrant that had be brought to justice. The Black Legend of Marshal Ruiz, deliberately called so to draw parallels to the Spanish Black Legend, argues that these horror stories had more truth than falsehood. Lewis Riley, a wealthy planter, became an American martyr after he was murdered in a requisition gone wrong. Several more accounts of violence and mayhem exist, for example the rape and murder of Margaret Patin, a young woman who was living alone after her husband joined the army. Many of the soldiers who escaped Louisiana with Scott or were captured by the Mexican army, related how they came back to find their houses destroyed and their women and children dead. Taylor himself found his plantation a smoldering ruin.

/Christiana-crpd2100x1400-56a4890b3df78cf77282ddb2.jpg)

Requisitioning of Louisianan cotton.

Ruiz also has his defenders, the supporters of the “White Legend”. They argue that Southern stories cannot be trusted and that the “Rape of Louisiana” was a greatly exaggerated event, if not a complete fabrication. They point to other accounts, such as the one of Howard Laplante, editor of a New Orleans newspaper, who admitted begrudgingly that the streets of New Orleans had never been freer of "cutthroats and petty thieves". Yet it’s doubtful that that newfound security was a result of Ruiz’s direct actions – the consensus is that it was an unintended consequence of the continuous presence of army units, who protected Ruiz’s life against assassination attempts. Rape during the occupation is more hotly debated.

Ruiz never tolerated rape in the army ranks and was known for swiftly executing any soldier who was found committing such acts. When the army was a cohesive unit that traveled together, it was easy to monitor all soldiers. But now that they were spread all over Louisiana, looking for food and cotton or patrolling rivers and cities, monitoring soldiers was difficult if not outright impossible. Further complicating matters was that women were not likely to come to the Marshal if they had been victims of sexual abuse. Doing so would be a mark of dishonor and shame, and thus soldiers knew they could get away with it most of the time.

In a society that considered women pure, almost perfect creatures such as the antebellum South, this kind of abuse was intolerable. “Will you allow the Mexican hordes to violate the fair daughters of the South?” Senator Calhoun asked his fellow South Carolinians. “No!” answered Liberal Representative from Georgia Alexander Stephens, “men from the Mississippi to the Potomac will lead the liberation of our sister state”. Stephens then added with grim fury that men from the Potomac to New England better do the same.

Stopping the rape of Louisiana became the rallying cry of American men, whether from the North or South. Private Thompson from Massachusetts enlisted in the army after reading reports of the occupation. “I never agreed nor will ever agree to the objectives of this war”, he wrote to his girlfriend, “but I can’t stand idle while those savages plunder and violate our sacred country”.

Newspaper ilustration showing two Mexican officers attacking a young lady.

The occupation of Louisiana proved to be a gold mine of propaganda for the Americans. Emperor Agustin II and Prime Minister Castillo were worried about the implications for Mexico and its standing on the international stage. Several MPs were worried as well. Benito Juarez, who would later become one of Mexico’s most important politicians but was back then just a minor representative, demanded an inquiry. The inquiry couldn’t find anything, concluding that Ruiz was not at fault. Many accused it of bias, but the consensus among historians is that it was true – Ruiz was doing everything he could.

The inquiry didn’t ease Castillo’s mind, and much less foreign concerns. A session of the British parliament discussed the “Louisiana situation”, with several MPs showing distaste for the uncivilized acts going on the occupied state. "The continuation of these attacks against the women of the Anglo-Saxon race cannot be tolerated" declared Home Secretary Lord Palmerston. “How can we support a nation that carries off such heinous crimes?” asked the governor of Hispaniola, Antonio Avila. Napoleon III also showed concern for crime in the AML.

Yet it seems that Castillo had overestimated how much damage Louisiana could make to the Mexican cause. Most Latin Americans were quick to dismiss the rape of Louisiana as gringo propaganda. Even if they believed it, most were willing to excuse the Mexicans, saying that Patterson and the Americans were committing far worse crimes in Veracruz. Latin Americans generally identified better with Mestizo, Catholic Mexico than with the Protestant White United States. A sense of shared culture and race with Mexico appeared in Latin America. Every insult towards Mexicans was thus an insult towards Chile, Colombia, La Plata and the rest of Latin America as well. This led to the raise of an “us vs them” mentality, with many powerful men urging cooperation with “our sister nation, with whom we’re joined together by culture and history”, in the words of Chilean ex-president Horacio Luna.

In Britain, popular opinion was not so much pro-Mexico as anti-United States. The US’ warmongering ways had rubbed British politicians the wrong way, especially war threats over the Oregon territory and attempts at economic coercion. Officially relations were cordial, and trade was actually in the rise, with the US buying millions of British guns and ammunition and Britain buying grain in turn. Yet the prevailing public sentiment was against the US. Many were somewhat amused by how the Empire of Liberty was waging a war of conquest. The satiric magazine Punch published a cartoon that showed the US learning the “family trade” of starting imperialists wars. A National Liberal MP denounced the Americans as “warmongering hypocrites”. Prime Minister Roberts commented dryly that the Americans had nobody to blame but themselves for the “Louisiana situation”. Still, Britain was not willing to intervene in the conflict for or against any side, and besides some warmings to the French and Americans, they remained neutral, quietly profiteering from the saltpeter and firearms trade.

Napoleon III trying to convince John Bull that the Louisiana Situation was nothing to worry about.

The French hate towards Americans could only “be compared to the American hate for Catholics”. Some disdain had quickly morphed into an open, virulent hate as reports of American atrocities in Veracruz and attacks against Catholics reached France. Memories of American “ungratefulness” after France helped the US during the Revolutionary War and of the US’ “betrayal” and the First Quasi-War re-emerged. A sense of commonness with Catholic Mexico developed, while Anglo-Saxon Protestant US was seen as the embodiment of everything France was not. Undoubtedly, some of the old hate towards Britain expressed itself in new hate for its former colony.

International reaction to the rape of Louisiana was not as dramatic as many expected. Countries that supported the Mexico or US before it were not swayed, and countries that favored neutrality weren’t concerned enough. However, the US propagandists never expected to sway any country’s opinion. The rape of Louisiana was far more useful to elicit nationalistic responses among the American youth. The occupation of Louisiana inspired fury and indignation among the people of the US. Other AML decrees caused enormous fury as well, but instead of indignation they inspired fear among Southern planters – the ones concerning slavery.

Mexico and Colombia were considered two of the most abolitionist countries in the time period. Many historians have contested the claim, arguing that although both nations were abolitionist, neither did anything beyond abolishing slavery for their afro populations, which were small compared to the US. Still, both nations’ founders were deeply against slavery and abolished it as soon as political conditions allowed it. While most Mexicans probably found slavery to be an evil, most probably were more concerned with other matters. However, as tensions with the United States rose most of Mexican politicians and reporters started to criticize American slavery. The South, the main force behind the war, was most heavily hit by these attacks.

Still, Mexico had allowed the Ducky of Texas to legalize slavery, but not the slave trade, as part of the compromise that prevented war in the 1840’s. But now that war had happened anyway, Mexico gripped with the question of what to do with the Texians and their slaves. Some proposed liberating all slaves immediately, but the Castillo government rejected the measure, afraid of the possible consequences. Castillo knew that the Americans would probably see such an action as a violation of the laws of war and would subsequently demanded economic compensation or for the slaves to be handed back.

Slavery in Texas.

Thus, instead of total abolition Parliament decided to only liberate the slaves owned by people who had taken up arms against the Mexican government. “If a man uses a rifle in an attempt to undermine a government, international law dictates that that government is well within its rights to confiscate said rifle. The same principle applies here – any slave used unwillingly by his masters in an attack against Mexico must be granted freedom” announced Ernesto García, representative for Sonora from the National Patriotic Party. The García doctrine was applied through the duchy, with dozens or even hundreds of slaves being liberated after their masters took up arms against Mexico. As the conflict moved more and more towards becoming a total war, so did Mexican opinions. Finally, in February 1863 an act of Parliament abolished the Duchy of Texas and decreed liberty of womb and marshal law, as a response to increasingly violent guerrilla warfare. Total abolition was still not decreed because Polk announced that any peace settlement would have to include economic compensation or the return of all slaves.

The situation in Louisiana was more delicate. While the Mexican government could claim authority over the former Duchy since Agustin II was also its Grand Duke, it couldn’t claim any sort of control over Louisiana. The AML had imposed marshal law, and the governor and some local authorities had been replaced by Mexican officers, but most of Louisiana’s constitution and laws remained intact. In fact, many trials were still being conducted by Louisianan courts. As first, Ruiz and his soldiers entered Louisiana with no intention of interfering with the institution of slavery, effectively adopting a “do nothing” policy. Eventually, however, events forced Ruiz to adopt an actual policy.

The first incident happened during the early stages of Ruiz’s campaign. One soldier from a Georgia company had brought his slave with him to army camps. That slave worked cooking meals for his master, but he had happened to overhear the company’s commander talking about Taylor’s next movement. Later that day he managed to escape and reach Ruiz’s lines. Ruiz was going to turn him away at first, until the slave told him what he had learned. Realizing that the information might be useful, Ruiz allowed him to stay. The slave, Samuel, started to work cooking meals for a Tejano Company. He would later settle in Mexico, adopting the surname of the Tejano company’s commander, Gonzales.

Samuel’s fate and the information he gave Ruiz proved to be of little consequence to Mexico or the war, but his escape had a great effect in the administration of Louisiana. Samuel’s owner came to Ruiz’s camp under flag of truce and asked for his slave. Ruiz was at first willing to hand Samuel over, but the Tejano company refused to cooperate. Their closeness to Texian slave owners had turned them into stark abolitionists. Ruiz decided to ask Samuel’s owner for a guarantee that Samuel would not be punished as a compromise. When the slave master refused, Ruiz decided that Samuel could stay with them.

Samuel’s case set a precedent. From that point on many more slaves would try to escape to Mexican lines, expecting to be offered refuge by sympathetic Mexicans. This escalated quickly – soon it wasn’t only slaves brought by soldiers that escaped, but also slaves from plantations in Louisiana and Mississippi. In most cases they did find refuge, being offered work cooking or carrying supplies in Mexican battalions.

Against his owner's wishes, a slave seeks refuge with Mexican soldiers.