You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Miranda's Dream. ¡Por una Latino América fuerte!.- A Gran Colombia TL

- Thread starter Red_Galiray

- Start date

- Status

- Not open for further replies.

Threadmarks

View all 76 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 62: The Balkan War Chapter 63: The Liberal Revolution Appendix: The Colombian National Army Appendix: The Colombian Cavalry Appendix: The Colombian Artillery Appendix: The Colombian Navy Chapter 64: From the Andes to the Caribbean Chapter 65: The Irrepressible Conflict

Chapter 22: The South Cone.

The South Cone

After the collapse of Congress Latin America, which had created a tense peace in the south cone, the tensions in the area increased. A particular critical spot was the Banda Oriental, composed of the Platinean state of Oriental Provinces and the Brazilian Rio Grande do Sul. The dispute over the area was a heritage from the colonial era of both nations, as both Spain and Portugal had fought several times for the total control of it. The Spanish performance in those conflicts was, however, mediocre at best, and thus the Banda had been eaten slowly by the Portuguese. This, together with the fact that the area almost fell under complete Portuguese control during the Independence War, only to be saved by the Oriental Revolution, was a particular sore spot for La Plata, specifically Buenos Aires, who still held aspirations of taking complete control of the country and re-taking the “rightful Platinean” territories.

La Plata, since the aftermath of the Independence Wars, had been governed by the Federal “Orientales”, due to the fact that San Martin, the only Independence leader who could contest Artigas power in the newborn state, had exiled himself to Europe. The Elections, open only to wealthy Catholic Male Criollos, were to elect the United Congress, which would then elect the President. That President, however, was just a figure head, with the real power being in the elites and military leaders of the most powerful state within the loose United Provinces. Normally, this would be Buenos Aires, but Artigas experience and influence meant that he could put his state of Provincias Orientales in the lead.

United Congress.

The elites of Buenos Aires were extremely bitter, especially because the Oriental policies were practically opposite of what the Porteños wanted. For example, the Orientales supported a free market while the Porteños wanted to install protectionism. One of the few things the Porteños managed to influence when it came to nationwide policies regarded the stance towards Britain and France. Buenos Aires was still angry over the British Invasions and the support it had showed to Colombia, and thus it managed to prevempt cooperation or investment, preferring to fall under the French sphere. Even then the Porteños weren’t happy at all when France asked them to open the Platinean rivers, but the Artigas government decided to agree on the basis that, with an aloof or even hostile Britain, La Plata needed a great power for protection.

During Congress Latin America, La Plata didn’t do much. The Platinean leadership knew that any war would make the system crash, something that not even Colombia seemed to realize at the time. Nonetheless, the high military men often advocated for an invasion of Paraguay or a retaking of the rest of the Banda Oriental, both risky prospects as Paraguay was a heavily militarized nation and the Brazilian Empire, though politically unstable, would be able to put a formidable defense or even win. Certain commanders were also worried about the logistical capacities of La Plata, which were, at best, nominal and the possible lack of cooperation between the states in case of war.

The Platinean Army had too much influence in the country as a result of a failed mobilization. No state was willing to disband its militias, especially in the atmosphere of distrust created by the Civil War (which started to be called “the Federal War”), with both Buenos Aires and Montevideo having huge armies who were more ready to face each other than to face the Brazilians. Overall, El Ejercito Unido was a very weak and ineffectual organization, whose only redeeming quality, also its only advantage over other countries like Brazil, was its great organization, which followed French standards. Neither Brazil nor Paraguay, the most probable opponents, were completely organized (though Paraguay did have an ace under its sleeve) and Chile, organized by Prussian standards, could simply not support a war thanks to the Andes.

Platinean Army.

Still, perhaps the greatest advantage of the Platinean Army was its experience. Brazil didn’t conduct a “proper” Independence War, and thus lacked experienced commanders, of which La Plata had many. Even after several great men, like San Martin, retired, and even with the lack of cooperation between the several militias, the Platinean leaders trusted that, in the event of war, the United Provinces would be able to trump their enemies.

As for internal policies, the “Indian question” was a hot topic. The American two stances had, unexpectedly, affected the Platinean possible positions, which ranged from a war to remove them, forced immigration or extend protections and try to assimilate them. As usual, the decision was split between the Porteños and the Orientales, and the debate reached a temporary halt with the Indian Defense Decree of the United Congress, which forbade Platinean armies from murdering Natives, but allowed them to relocate them if “the situation so called”.

When it came to economy, La Plata had become an important exporter of cattle and wheat, but the bad relations with Britain, political instability and the aforementioned Indian raids limited the economic grow of the young nation. Still, La Plata was prosperous and its life conditions were among the best.

The Platinean farms became a huge supplier of foood to Europe.

La Plata wanted to appeal to immigrants, but most of the land was in the hands of landowners, unlike Colombia, which enjoyed having almost 70% of its land under state control. The fights between the Oriental led Government and the different Warlords (there isn’t, really, any other term suitable to define them) stopped any Agrarian Reform from happening. For example, who should be the one doing the repartition of the Patagonian or Indian land? Does the Central Government have any authority over the land of Buenos Aires? Still, La Plata received a good number of immigrants, mostly Italian ones.

The Brazilian Empire, the most immediate neighbor and rival of the United Provinces faced its own set of problems. The Independence, just like in most of Latin America, didn’t really bring any meaningful changes to Brazilian society or economy, and that angered a lot not people who hoped to enter a new “golden age” of liberty. They were still under a monarchy, with their Emperor being none other than a former member of the Portuguese monarchy that had ruled them beforehand; they still had to deal with slavery and a mostly extractive economy; and they were still oppressed by the elites, only that this time the Wealthy Portuguese Criollo elites were substituted with, almost literally, their children, the Wealthy Brazilian Criollo elites. The pyramid had become a trapezoid.

Unlike Agustin’s Mexico, Don Pedro’s Brazil wasn’t very stable, and was traped between two decisions most of the time. Should the Empire build a powerful military that would protect it but might threaten the government as well? Should Brazil claim Oriental Provinces on the basis that the United Congress had ceded them to Portugal and the Empire, as successor of the colony, was its rightful owner? Or should it evade war with La Plata? Should it side with France or with the British Empire?

By the grace of God, Emperor Pedro the I of the Imperial House of Brazil.

The hottest debate was about the powers the Emperor would hold. Pedro I was a liberal, and he fully supported the new liberal regimes France had been propping up, but his ideals faced backlash by most of the patriarchal and conservationist Brazil. Thus, Don Pedro decided that a strong constitution that adjudicated enormous powers to him would be necessary to hold the country together and guide it. This is called the “strong hand” approach, which contrasted with the “soft hand” approach, tough neither would be called that until a couple of decades into the XXth century. Basically, the former said that a dictatorship was the only way to control and guide a newborn nation (Francia, De la Mar and Bolivar supported it) and the latter said that democracy was possible (Santander and Miranda were its main proponents). In spite of his liberal leaning, Don Pedro approved O constituição do Império and ruled Brazil with an iron fist.

The actions of the Emperor were controversial and heavily criticized through Latin America. He crushed rebellions in the Banda Oriental and the north of Brazil with extreme violence and desmeasured force, almost provoking a war with the neighboring La Plata, which was only prevented by a Franco-British delegation threatening with blockading the entire South American Atlantic coast.

Brazil faced several political crises through Congress Latin America and the decade of the forties, but the “Imperial Alliance” between it and the Mexican Empire meant that the Brazilian economy was strong. Still, there was unused potential there. For instance, Don Pedro’s cotinous negation to enter anyone’s sphere limited levels of investment and immigration from France and the United Kingdom, lack of cooperation with other Latin American countries, a still mostly extractive economy and various conflicts that had Brazil in the brink of civil war damaged and prevented the economy from reaching its full potential.

Arrecife, 1830.

Don Pedro would stay in power until around 1836, when he finally had had enough and decided to abdicate in favor of his son, who would come to be known as Emperor Pedro II. He was still only a child of around eleven years, and thus was really unprepared to become the Emperor of such a huge country. Pedro I had wanted to go back to Portugal, but the development there prevented him from doing so, so he stayed in Brazil and dedicated himself to a live of luxury and pleasures. His son would come to deeply resent him from that.

Since Pedro I didn’t really want to take care of neither Brazil nor his son, he named José Bonifácio de Andrada e Silva, a friend he deeply trusted, Prime Minister or Brazil (the position was officially called the Secretary of State for Imperial Affairs) and Pedro de Araújo Lima, the Marquis of Olinda, a Imperial regent. Bonifacio and Araujo didn’t like each other, and thus both wanted to influence the young ruler. Araujo towards monarchism, even absolute; Bonifacio towards a parliamentary monarchy. This caused deep trust issues to the young Emperor, who only ever found love and guidance in his governess, Mariana de Verna.

Mariana de Verna, nicknamed Dadama by the young Emperor.

Easily influenced and manipulated, immature and not yet prepared, the childhood of Pedro II was lonely and sad. Industrialist, elites and politicians played with him, and this led to great instability through the Empire. Though Bonifacio remained Secretary of State, the President of Senate, the one that hold the most effective power in light of the fights between the Secretary and the Regent, was subject to sudden and continuous changes. The average term for a President of Senate was around a few months.

Another critical spot was slavery, which the elites were hell bent in keeping, and insurgency in the Banda Oriental, were Artigas' ideals and the memory of the "Orientalidad" had not yet died.

As for the Imperial Brazilian Army, it was not trained according to any European Standards, but it wasn’t weak or disorganized by any means. The Brazilian economy was stronger than the Platinean one, but still they were very dependant in foreign goods, especially British and French ones. The Colombo-Peruvian War had shown that In case of war in Latin America, Britain and France were likely to squabble for a while before settling in neither supporting its sphere members, but that was when Colombia, “El Perrito Inglés”, was the one threatened. Just like the US could expect France to support Mexico in case of war (especially with the British almost continually angry with them over their antics), sphere-less Brazil could expect France to support La Plata. Still, that wasn’t a foregone conclusion, and it was possible that La Plata could not receive support of any nation, and thus Brazil would be free to crush it after blockading its main ports. The only problems was that the pitiful Brazilian navy would be likely be destroyed in the first weak by the Oriental Fleet in case of War, limiting any Brazilian war-strategy to taking control of the Platine Rivers (where the enemy was the more or less equally matched Porteño River Navy) and occupy Oriental Provinces. Another concern of the Brazilian Military was its lack of experience (most experienced troops had gone to Portugal in the wake of Independence) and the fact that it might be render leaderless if the Emperor hadn’t reached adulthood by the time the war started.

O exercito Imperial.

However, there was one little nation, which was a torn in the side of both La Plata and Brazil. One little nation that could exercise certain control in the Platinean Rivers and prevented both countries from conducting certain offensives. One nation that controlled territory both the United Provinces and the Empire claimed. Paraguay had been moved into an era of isolationism and quiet industrialization after the collapse of Congress Latin America. Its army was trained by Prussian standards; it was not as dependant in foreign goods as other nations (Colombia and, perhaps, Mexico being the only other nations that could claim they could conduct a war only by themselves); and it didn’t face as much instability as its neighbours.

Some people, like Santa Cruz, considered Francia’s government there a sign of the triumph of “La Mano Dura”. This is arguably true, as Francia’s Paraguay really was the most successful and pure example of that doctrine, even when there were somewhat ironic claims that he was too soft. His policies of promoting Guarani, interracial marriages and criticizing La Plata’s actions against the Indigenas were considered distasteful and improper.

There's certain nostalgia of the years of Francia, sometimes considered Paraguay's best.

The future was uncertain for the Southern Cone when 1840 started. The setup seemed ideal for a war, and nobody seemed what the future would bring. A series of events starting with Francia’s death in 1840 and some concerns and crisis in Chile would end up changing the South Cone and starting what’s allegally one of its worse periods

After the collapse of Congress Latin America, which had created a tense peace in the south cone, the tensions in the area increased. A particular critical spot was the Banda Oriental, composed of the Platinean state of Oriental Provinces and the Brazilian Rio Grande do Sul. The dispute over the area was a heritage from the colonial era of both nations, as both Spain and Portugal had fought several times for the total control of it. The Spanish performance in those conflicts was, however, mediocre at best, and thus the Banda had been eaten slowly by the Portuguese. This, together with the fact that the area almost fell under complete Portuguese control during the Independence War, only to be saved by the Oriental Revolution, was a particular sore spot for La Plata, specifically Buenos Aires, who still held aspirations of taking complete control of the country and re-taking the “rightful Platinean” territories.

La Plata, since the aftermath of the Independence Wars, had been governed by the Federal “Orientales”, due to the fact that San Martin, the only Independence leader who could contest Artigas power in the newborn state, had exiled himself to Europe. The Elections, open only to wealthy Catholic Male Criollos, were to elect the United Congress, which would then elect the President. That President, however, was just a figure head, with the real power being in the elites and military leaders of the most powerful state within the loose United Provinces. Normally, this would be Buenos Aires, but Artigas experience and influence meant that he could put his state of Provincias Orientales in the lead.

United Congress.

The elites of Buenos Aires were extremely bitter, especially because the Oriental policies were practically opposite of what the Porteños wanted. For example, the Orientales supported a free market while the Porteños wanted to install protectionism. One of the few things the Porteños managed to influence when it came to nationwide policies regarded the stance towards Britain and France. Buenos Aires was still angry over the British Invasions and the support it had showed to Colombia, and thus it managed to prevempt cooperation or investment, preferring to fall under the French sphere. Even then the Porteños weren’t happy at all when France asked them to open the Platinean rivers, but the Artigas government decided to agree on the basis that, with an aloof or even hostile Britain, La Plata needed a great power for protection.

During Congress Latin America, La Plata didn’t do much. The Platinean leadership knew that any war would make the system crash, something that not even Colombia seemed to realize at the time. Nonetheless, the high military men often advocated for an invasion of Paraguay or a retaking of the rest of the Banda Oriental, both risky prospects as Paraguay was a heavily militarized nation and the Brazilian Empire, though politically unstable, would be able to put a formidable defense or even win. Certain commanders were also worried about the logistical capacities of La Plata, which were, at best, nominal and the possible lack of cooperation between the states in case of war.

The Platinean Army had too much influence in the country as a result of a failed mobilization. No state was willing to disband its militias, especially in the atmosphere of distrust created by the Civil War (which started to be called “the Federal War”), with both Buenos Aires and Montevideo having huge armies who were more ready to face each other than to face the Brazilians. Overall, El Ejercito Unido was a very weak and ineffectual organization, whose only redeeming quality, also its only advantage over other countries like Brazil, was its great organization, which followed French standards. Neither Brazil nor Paraguay, the most probable opponents, were completely organized (though Paraguay did have an ace under its sleeve) and Chile, organized by Prussian standards, could simply not support a war thanks to the Andes.

Platinean Army.

Still, perhaps the greatest advantage of the Platinean Army was its experience. Brazil didn’t conduct a “proper” Independence War, and thus lacked experienced commanders, of which La Plata had many. Even after several great men, like San Martin, retired, and even with the lack of cooperation between the several militias, the Platinean leaders trusted that, in the event of war, the United Provinces would be able to trump their enemies.

As for internal policies, the “Indian question” was a hot topic. The American two stances had, unexpectedly, affected the Platinean possible positions, which ranged from a war to remove them, forced immigration or extend protections and try to assimilate them. As usual, the decision was split between the Porteños and the Orientales, and the debate reached a temporary halt with the Indian Defense Decree of the United Congress, which forbade Platinean armies from murdering Natives, but allowed them to relocate them if “the situation so called”.

When it came to economy, La Plata had become an important exporter of cattle and wheat, but the bad relations with Britain, political instability and the aforementioned Indian raids limited the economic grow of the young nation. Still, La Plata was prosperous and its life conditions were among the best.

The Platinean farms became a huge supplier of foood to Europe.

La Plata wanted to appeal to immigrants, but most of the land was in the hands of landowners, unlike Colombia, which enjoyed having almost 70% of its land under state control. The fights between the Oriental led Government and the different Warlords (there isn’t, really, any other term suitable to define them) stopped any Agrarian Reform from happening. For example, who should be the one doing the repartition of the Patagonian or Indian land? Does the Central Government have any authority over the land of Buenos Aires? Still, La Plata received a good number of immigrants, mostly Italian ones.

The Brazilian Empire, the most immediate neighbor and rival of the United Provinces faced its own set of problems. The Independence, just like in most of Latin America, didn’t really bring any meaningful changes to Brazilian society or economy, and that angered a lot not people who hoped to enter a new “golden age” of liberty. They were still under a monarchy, with their Emperor being none other than a former member of the Portuguese monarchy that had ruled them beforehand; they still had to deal with slavery and a mostly extractive economy; and they were still oppressed by the elites, only that this time the Wealthy Portuguese Criollo elites were substituted with, almost literally, their children, the Wealthy Brazilian Criollo elites. The pyramid had become a trapezoid.

Unlike Agustin’s Mexico, Don Pedro’s Brazil wasn’t very stable, and was traped between two decisions most of the time. Should the Empire build a powerful military that would protect it but might threaten the government as well? Should Brazil claim Oriental Provinces on the basis that the United Congress had ceded them to Portugal and the Empire, as successor of the colony, was its rightful owner? Or should it evade war with La Plata? Should it side with France or with the British Empire?

By the grace of God, Emperor Pedro the I of the Imperial House of Brazil.

The hottest debate was about the powers the Emperor would hold. Pedro I was a liberal, and he fully supported the new liberal regimes France had been propping up, but his ideals faced backlash by most of the patriarchal and conservationist Brazil. Thus, Don Pedro decided that a strong constitution that adjudicated enormous powers to him would be necessary to hold the country together and guide it. This is called the “strong hand” approach, which contrasted with the “soft hand” approach, tough neither would be called that until a couple of decades into the XXth century. Basically, the former said that a dictatorship was the only way to control and guide a newborn nation (Francia, De la Mar and Bolivar supported it) and the latter said that democracy was possible (Santander and Miranda were its main proponents). In spite of his liberal leaning, Don Pedro approved O constituição do Império and ruled Brazil with an iron fist.

The actions of the Emperor were controversial and heavily criticized through Latin America. He crushed rebellions in the Banda Oriental and the north of Brazil with extreme violence and desmeasured force, almost provoking a war with the neighboring La Plata, which was only prevented by a Franco-British delegation threatening with blockading the entire South American Atlantic coast.

Brazil faced several political crises through Congress Latin America and the decade of the forties, but the “Imperial Alliance” between it and the Mexican Empire meant that the Brazilian economy was strong. Still, there was unused potential there. For instance, Don Pedro’s cotinous negation to enter anyone’s sphere limited levels of investment and immigration from France and the United Kingdom, lack of cooperation with other Latin American countries, a still mostly extractive economy and various conflicts that had Brazil in the brink of civil war damaged and prevented the economy from reaching its full potential.

Arrecife, 1830.

Don Pedro would stay in power until around 1836, when he finally had had enough and decided to abdicate in favor of his son, who would come to be known as Emperor Pedro II. He was still only a child of around eleven years, and thus was really unprepared to become the Emperor of such a huge country. Pedro I had wanted to go back to Portugal, but the development there prevented him from doing so, so he stayed in Brazil and dedicated himself to a live of luxury and pleasures. His son would come to deeply resent him from that.

Since Pedro I didn’t really want to take care of neither Brazil nor his son, he named José Bonifácio de Andrada e Silva, a friend he deeply trusted, Prime Minister or Brazil (the position was officially called the Secretary of State for Imperial Affairs) and Pedro de Araújo Lima, the Marquis of Olinda, a Imperial regent. Bonifacio and Araujo didn’t like each other, and thus both wanted to influence the young ruler. Araujo towards monarchism, even absolute; Bonifacio towards a parliamentary monarchy. This caused deep trust issues to the young Emperor, who only ever found love and guidance in his governess, Mariana de Verna.

Mariana de Verna, nicknamed Dadama by the young Emperor.

Easily influenced and manipulated, immature and not yet prepared, the childhood of Pedro II was lonely and sad. Industrialist, elites and politicians played with him, and this led to great instability through the Empire. Though Bonifacio remained Secretary of State, the President of Senate, the one that hold the most effective power in light of the fights between the Secretary and the Regent, was subject to sudden and continuous changes. The average term for a President of Senate was around a few months.

Another critical spot was slavery, which the elites were hell bent in keeping, and insurgency in the Banda Oriental, were Artigas' ideals and the memory of the "Orientalidad" had not yet died.

As for the Imperial Brazilian Army, it was not trained according to any European Standards, but it wasn’t weak or disorganized by any means. The Brazilian economy was stronger than the Platinean one, but still they were very dependant in foreign goods, especially British and French ones. The Colombo-Peruvian War had shown that In case of war in Latin America, Britain and France were likely to squabble for a while before settling in neither supporting its sphere members, but that was when Colombia, “El Perrito Inglés”, was the one threatened. Just like the US could expect France to support Mexico in case of war (especially with the British almost continually angry with them over their antics), sphere-less Brazil could expect France to support La Plata. Still, that wasn’t a foregone conclusion, and it was possible that La Plata could not receive support of any nation, and thus Brazil would be free to crush it after blockading its main ports. The only problems was that the pitiful Brazilian navy would be likely be destroyed in the first weak by the Oriental Fleet in case of War, limiting any Brazilian war-strategy to taking control of the Platine Rivers (where the enemy was the more or less equally matched Porteño River Navy) and occupy Oriental Provinces. Another concern of the Brazilian Military was its lack of experience (most experienced troops had gone to Portugal in the wake of Independence) and the fact that it might be render leaderless if the Emperor hadn’t reached adulthood by the time the war started.

O exercito Imperial.

However, there was one little nation, which was a torn in the side of both La Plata and Brazil. One little nation that could exercise certain control in the Platinean Rivers and prevented both countries from conducting certain offensives. One nation that controlled territory both the United Provinces and the Empire claimed. Paraguay had been moved into an era of isolationism and quiet industrialization after the collapse of Congress Latin America. Its army was trained by Prussian standards; it was not as dependant in foreign goods as other nations (Colombia and, perhaps, Mexico being the only other nations that could claim they could conduct a war only by themselves); and it didn’t face as much instability as its neighbours.

Some people, like Santa Cruz, considered Francia’s government there a sign of the triumph of “La Mano Dura”. This is arguably true, as Francia’s Paraguay really was the most successful and pure example of that doctrine, even when there were somewhat ironic claims that he was too soft. His policies of promoting Guarani, interracial marriages and criticizing La Plata’s actions against the Indigenas were considered distasteful and improper.

There's certain nostalgia of the years of Francia, sometimes considered Paraguay's best.

The future was uncertain for the Southern Cone when 1840 started. The setup seemed ideal for a war, and nobody seemed what the future would bring. A series of events starting with Francia’s death in 1840 and some concerns and crisis in Chile would end up changing the South Cone and starting what’s allegally one of its worse periods

The future was uncertain for the Southern Cone when 1840 started. The setup seemed ideal for a war, and nobody seemed what the future would bring. A series of events starting with Francia’s death in 1840 and some concerns and crisis in Chile would end up changing the South Cone and starting what’s allegally one of its worse periods

Dammit.

Chile, organized by Prussian standards, could simply not support a war thanks to the Andes.

But still a Prussian army. I'm good.

I love the grim foreshadowing you're giving to every American nation... None of us will be saved from the Decades of Darkness...

Oh snap, here's comes a Paraguayan War. Good luck, Little Nation That Could! (I have a fascination with Paraguay history for some reason)

Oh snap, here's comes a Paraguayan War. Good luck, Little Nation That Could! (I have a fascination with Paraguay history for some reason)

And one of the best South American allies you can get in Vic II. They pack a punch. Without them, I couldn't have annexed Potosí,(which I wanted to make it a second La Serena) because I was fighting two fronts already.

But still a Prussian army. I'm good.

Chile can be considered to have the better army in the entire continent right now. The United States Army and the Colombian Army are unfunded and tiny, the Brazilian army is untrained, the Platinean one suffers from lack of cooperation and the Mexican Army, though well funded and trained, is devoid of good leadership and Mexico's logistical capacities are minimal.

I love the grim foreshadowing you're giving to every American nation... None of us will be saved from the Decades of Darkness...

Thanks. It won't be so bad though. OTL this period was also filled with civil wars and conflict, and in some aspects the ITTL future would be considered better.

Oh snap, here's comes a Paraguayan War. Good luck, Little Nation That Could! (I have a fascination with Paraguay history for some reason)

Paraguay is going to shine, promise. At least, if either La Plata or Brazil attack, they will be faced with a great surprise.

Chapter 23: Pacific War.

The Pacific War.

Though the Independence of Chile is generally oversimplified in history books that don-t deal specifically with the topic in order to fit it in one page or less, it was, actually, a very messy affair. We, unfortunately, are not able to provide an adequate summary to this very important event and thus will have to be brief.

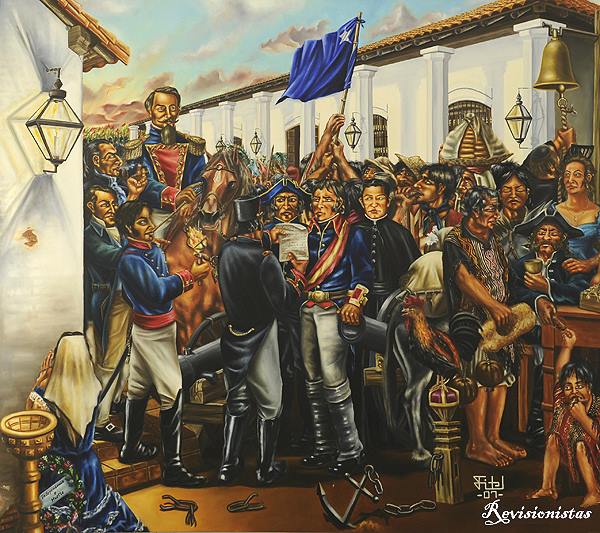

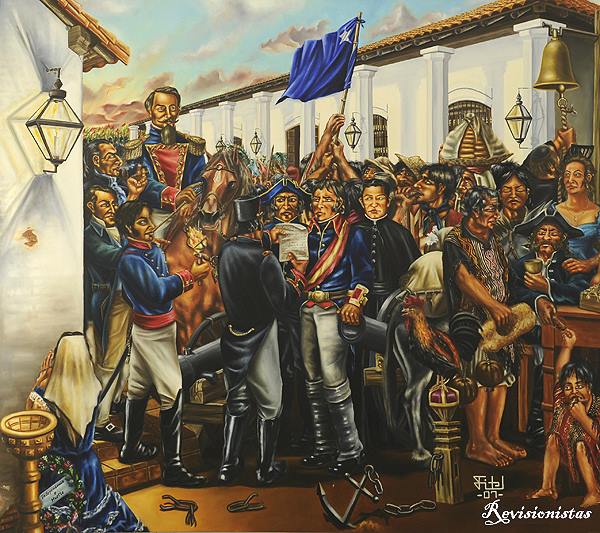

After the loyalist efforts all through South America started to collapse with the Fall of Quito and the start of the Colombian March on Lima, the Patriot Junta of Chile was able to capture ground from the Royalist Junta that had been governing the colony. O'Higgins, Freire and Blanco Encalada would form a triumvirate and led Chile to victory, capturing Santiago a few weeks before the Colombian tricolor rose in Lima. The first one, O’Higgins, was by far the most powerful, but he still had to rivals, Diego Portales and Carrera.

Carrera would end up killed towards the end of Congress Latin America, while Portales would continue to be O’Higgins greatest rival until O’Higgins’ death in 1827. A brief power struggle, sometimes defined as a civil war would ensue until a rigged elections were started and Fernando Errázuriz Aldunate was elected president. The president of Chile, however, was almost powerless during these years and every political decision was took by a junta of Oligarchs and Military men called “The London Boys”[1] as most of them had ties with Britain and were educated in the best London universities.

People celebrating the Chilean Independence.

Chile was a stable republic, though whether or not it can be called a democracy is still up to debate. During the decade of Congress Latin America Chile was one of the most successful countries in the entire continent, and by the 1840’s Chile had, without doubt, the best army in the continent and one of the best navies. The truth is, however, that even though these achievements seem impressive, they were not all that great in reality. All the other armies in the entire Americas, with the possible exception of the Mexican Imperial Army and the Army of Paraguay, were unfounded, leaderless, untrained, disorganized or undersupplied, or even all at the same time. Finally, the Chilean Navy might have looked impressive in paper, but it was actually rather pathetic. Most of the blame of it can be put under O’Higgins, who wanted to disband it after the Independence War but only refrained from doing so due to the threat of Spain (the Peace of Madrid hadn’t been signed yet) and the London Boys decided to keep it upon seeing how the Peruvian Navy utterly smashed the Colombians during their war. A rather common saying during the age was that Chile had five ships to every American ship… the only thing not mentioned being that every one of the Chilean ships were canoes and the American ship was a battleship.

While Mexico and America clashed thanks to Texas and the Great North, and war between Paraguay, La Plata and Brazil for some “silly damn thing in Oriental Provinces”[2] seemed likely, Chile had its own concerns. Peru was practically not a threat anymore. Cruz may had tried to make Peru great again (again) but he was still only a figure head similar to Leroy in Haiti, in other words, if he did as much as go against any Colombian interest, the Colombians would give carte blanche to the Peruvian elites and they would depose him. Chile was one of Colombia’s closest allies, so attacking Chile was naturally a bad idea for Peru, whose economy Santander had made sure was so dependant in Colombia it would immediately collapse if Colombia withdrew her support.

Charkas, on the other hand, was completely independent from Colombia, though still an ally. During the Colombo-Peruvian War it had started to flirt with La Plata, and even after the war Colombia had been unable to restore its control over it. Politically, economically and military independent, but very paranoid and poor, Charkas started a massive Military-Industrial complex and proto-Nationalist rhetoric against both Chile and Paraguay. The Chilean leadership knew, however, that a war between Charkas and Paraguay was not likely, as the Paraguayan leaders knew such a thing would let them exposed to either Platinean or Brazilian attacks, so al that military buildup could be against only one country.

Jose Miguel de Velasco Franco, was the lattest of several Charkean presidents who generally only lasted a few months. He was unusual in that we was always able to come back.

This was not helped by the tariff war between both countries. This “war” was an attempt to sunk each other’s economy, but it only managed to weaken both without a clear victor. Nonetheless, a beneficial side effect for Charkas ensued, as the London Boys lost most of their power and were forced to call to elections again. These elections quickly descended into chaos and anarchy, as two factions, the Conservatives and the Liberals, faced each other again. This was the moment in which Portales re-entered the political scene of Chile.

Portales would end up leading the Conservatives to victory and assuming absolute control of Chile, as a de facto Dictator. The liberals contested this, and the War of Colors started in 1842. This war, called like this because each side flew a color, blue for conservatives and yellow for liberals respectively, was not so much an armed conflict with peaceful intervals than a cold war with violent intervals. Colombia was worried, obviously, but it couldn’t do anything thanks to a crisis it had to deal with in the Caribbean[3]. La Plata and Brazil both stayed neutral, but Charkas decided to profit from the situation.

Charkas started to support Portales, who at first was very successful in his battle against the Liberals, but his luck took a turn for the worse when the Caribbean Crisis ended and Colombia decided to profit from the war as well, supplying the Liberals and trying o create yet another state completely dependent on it.

Diego Portales.

Colombian’s greater economy, and the fact that Charkas was also somewhat dependent on it, ensured that the Liberals eventually won and Portales had to flee to Peru. But Charkas was not satisfied. The tension were great, Chile was weak and had no allies, with the exception of Colombia. The benefits from a war could have been potentially enormous, especially if either side managed complete control of the coast. Guano trade had completely boomed, and with Chile in crisis, Peru (or rather, its overlord Colombia) had become very rich. Charkas was not able to exploit its guano, and Chile had not been able until that moment. A swift attack in a Chile that was already down would be enough, it would give Charkas all that profitable guano and eliminate all its problems.

The only thing against the great Charkean plans for glory was Colombia, but the Charkas were willing to bet that, in case of war, the Colombian course of action would be selling weapons to both sides (to Charkas through Peru, to Chile through sea) for maximum profit. Finally, the last Charkean ambition concerned Peru. Santa Cruz had showed interest in a confederation, if only to free Peru from the Colombian yoke. Perhaps by selling that guano Charkas could become strong enough to join Peru, defeat Colombia and become the premier South American power… after all, things weren’t going well in the South Cone after the death of Francia and Colombia was through some difficulties too.

Charkas' future and plans for glory seemed secured once Colombia went through its Grand Crisis and thus Santa Cruz was able to take absolute control of Peru and totally independize it from Colombia. He would go to Charkas, and in a secret treaty, and taking advantage of the Platine War being a distraction for La Plata, he declared the Confederation and started a war against Chile.

A surviving photo of Andres de Santa Cruz.

Chile was disunited and weak, freshly out from a Civil War and, thanks to Peru, cut from anyone who could have supplied it. However, it had a great advantage, and that was that in order to win the war the Peruvo-Charkean alliance had to effectively win, while Chile only had not to lose. Thus, the Chilean Navy adopted a defensive doctrine while the Army moved in order to stop any Charkean offensive that miraculously managed to go through the Atacama Dessert. Meanwhile all of this happened, behind the curtains negotiations and planning were undertaken to transform the pitiful river badges of Chile into a proper fleet.

It is a little sad that all this planning was actually unnecessary, as Peru was utterly and completely unprepared for a war. Colombia had been actively working to keep it weak, and thus the Peruvian army was nonexistent and the Peruvian Navy could have been dispatched easily had the Chilean commanders actually tried to engage in offensive instead of gazing at the enemy in fear. Charkas was unable to do anything in land, and their Navy was the most pitiful, being described by a Colombian observer as something that barely floated.

As for Colombia, the Charkean predictions turned out to be right, and with the British deciding to stay neutral (as per their accords with the French earlier that decade) and the French busy, this left only one country as possible supplier. Colombia sold cheap, but usually low quality weapons to both Charkas and Peru, while also selling them to Chile, all for great profit. It is noted that the Colombian arms, at first knock-outs of British and French models, started to improve in quality and thus became more expensive with time, but by then it was too late and not buying arms would mean leaving their armies unsupplied.

The Confederation and Chile face each other in the battlefield.

By mid-1844 Chile was finally able to conduct operations against the Peruvian Navy, and completely and utterly smashed them in several battles. By mid-1845 Chile was able to establish supply lines and conduct an invasion of Charkas, defeating their army in several battles as well. Chile, following the Prussian traditions and able to buy the better weapons the Colombians had (which were, admittedly, still cheap and bad) looked like the definite winners of the war. In 1846 the Chilean leadership, which was now again a junta of Oligarchs and Military men called the Santafe Boys (they were still educated in London, but their ties were with Colombia), was planning to land in Peru and even take Lima, but an event in Peru changed everything.

In March 14, 1846 the Semi Centennial Revolutions started with the overthrown of Santa Cruz by an association of Liberals who wanted democracy and Liberty. Know only as the Front of Liberty (Frente de la Libertad) and with the blessing of Colombia, who had by this point moved out of its problems, they installed a democratic modern Republic that was, if not a Colombian puppet anymore, a very close ally.

Santa Cruz had to flee to Colombia, as it wouldn't allow the new Peruvian government to execute him but wouldn't indulge his megalomaniac dreams of conquest either. Leaderless and practically already defeated, Charkas collapsed overnight and the Chileans were able to hold a new offensive, capturing their capital, the city of San Andres[4].

The original Chilean plans were to annex the entire Charkean coast (leaving them without a sea access) and a little part of Peru. Instead, and in the Peace of San Andres the map of the are was re-drawn. At the end every party was happy, as Chile obtained all the nitrates and guano and the territories they wanted, Peru didn’t lose that much after all (and had the Chincha island Colombia had taken returned, albeit now with their guano completely exploited) and Charkas, in spite of its almost total defeat still had a little sea access, known as the Charkean Corridor. Charkas was, above all, grateful to Colombia, who it looked up to as some kind of savior, fact helped by the cooperation of the new democratically elected President, Jose Ballivian, with Colombia in industry, economy and international politics.

Peace was restored, and what’s more important to Colombia, all the nations involved ended up heavily in debt with her and dependent in her due to the war, but also, and what's more rare in cases like this one, grateful to her. In the eyes of Chile Colombia was the savior that helped to create a lasting peace, helped to develop the Chilean industry, helped to preserve democracy and helped it to win through the selling of arms. In the eyes of Charkas, Colombia was the savior who prevented the Chilean beast from destroying it, Colombia was the savior that allowed it to retain a sea access and instaured democracy for the first time. Both nations would become Colombian allies ever since.

Map of the changes made by the Treaty of San Andres (1846). Chile annexed most of the territory in dispute, except for a tiny strip given to Charkas so that it could have an access to the sea. That territory, known as the Charkean Corridor, was originally Peruvian, so Charkas also ceded one of its Amazonians territories to Peru.

_________________________________

[1]Yeah, I'm referencing the infamous Chicago Boys of Pinochet here.

[2]Reference to Bismarck and his prediction of WWI.

[3]All this deal with Colombia and Peru will be explained in a future update. Suffice to say that Peru will become the cradle of South American liberty and freedom.

[4]OTL Sucre. As Sucre didn't have anything to do with the Charkean independence, it conserved its colonial name.

Though the Independence of Chile is generally oversimplified in history books that don-t deal specifically with the topic in order to fit it in one page or less, it was, actually, a very messy affair. We, unfortunately, are not able to provide an adequate summary to this very important event and thus will have to be brief.

After the loyalist efforts all through South America started to collapse with the Fall of Quito and the start of the Colombian March on Lima, the Patriot Junta of Chile was able to capture ground from the Royalist Junta that had been governing the colony. O'Higgins, Freire and Blanco Encalada would form a triumvirate and led Chile to victory, capturing Santiago a few weeks before the Colombian tricolor rose in Lima. The first one, O’Higgins, was by far the most powerful, but he still had to rivals, Diego Portales and Carrera.

Carrera would end up killed towards the end of Congress Latin America, while Portales would continue to be O’Higgins greatest rival until O’Higgins’ death in 1827. A brief power struggle, sometimes defined as a civil war would ensue until a rigged elections were started and Fernando Errázuriz Aldunate was elected president. The president of Chile, however, was almost powerless during these years and every political decision was took by a junta of Oligarchs and Military men called “The London Boys”[1] as most of them had ties with Britain and were educated in the best London universities.

People celebrating the Chilean Independence.

Chile was a stable republic, though whether or not it can be called a democracy is still up to debate. During the decade of Congress Latin America Chile was one of the most successful countries in the entire continent, and by the 1840’s Chile had, without doubt, the best army in the continent and one of the best navies. The truth is, however, that even though these achievements seem impressive, they were not all that great in reality. All the other armies in the entire Americas, with the possible exception of the Mexican Imperial Army and the Army of Paraguay, were unfounded, leaderless, untrained, disorganized or undersupplied, or even all at the same time. Finally, the Chilean Navy might have looked impressive in paper, but it was actually rather pathetic. Most of the blame of it can be put under O’Higgins, who wanted to disband it after the Independence War but only refrained from doing so due to the threat of Spain (the Peace of Madrid hadn’t been signed yet) and the London Boys decided to keep it upon seeing how the Peruvian Navy utterly smashed the Colombians during their war. A rather common saying during the age was that Chile had five ships to every American ship… the only thing not mentioned being that every one of the Chilean ships were canoes and the American ship was a battleship.

While Mexico and America clashed thanks to Texas and the Great North, and war between Paraguay, La Plata and Brazil for some “silly damn thing in Oriental Provinces”[2] seemed likely, Chile had its own concerns. Peru was practically not a threat anymore. Cruz may had tried to make Peru great again (again) but he was still only a figure head similar to Leroy in Haiti, in other words, if he did as much as go against any Colombian interest, the Colombians would give carte blanche to the Peruvian elites and they would depose him. Chile was one of Colombia’s closest allies, so attacking Chile was naturally a bad idea for Peru, whose economy Santander had made sure was so dependant in Colombia it would immediately collapse if Colombia withdrew her support.

Charkas, on the other hand, was completely independent from Colombia, though still an ally. During the Colombo-Peruvian War it had started to flirt with La Plata, and even after the war Colombia had been unable to restore its control over it. Politically, economically and military independent, but very paranoid and poor, Charkas started a massive Military-Industrial complex and proto-Nationalist rhetoric against both Chile and Paraguay. The Chilean leadership knew, however, that a war between Charkas and Paraguay was not likely, as the Paraguayan leaders knew such a thing would let them exposed to either Platinean or Brazilian attacks, so al that military buildup could be against only one country.

Jose Miguel de Velasco Franco, was the lattest of several Charkean presidents who generally only lasted a few months. He was unusual in that we was always able to come back.

This was not helped by the tariff war between both countries. This “war” was an attempt to sunk each other’s economy, but it only managed to weaken both without a clear victor. Nonetheless, a beneficial side effect for Charkas ensued, as the London Boys lost most of their power and were forced to call to elections again. These elections quickly descended into chaos and anarchy, as two factions, the Conservatives and the Liberals, faced each other again. This was the moment in which Portales re-entered the political scene of Chile.

Portales would end up leading the Conservatives to victory and assuming absolute control of Chile, as a de facto Dictator. The liberals contested this, and the War of Colors started in 1842. This war, called like this because each side flew a color, blue for conservatives and yellow for liberals respectively, was not so much an armed conflict with peaceful intervals than a cold war with violent intervals. Colombia was worried, obviously, but it couldn’t do anything thanks to a crisis it had to deal with in the Caribbean[3]. La Plata and Brazil both stayed neutral, but Charkas decided to profit from the situation.

Charkas started to support Portales, who at first was very successful in his battle against the Liberals, but his luck took a turn for the worse when the Caribbean Crisis ended and Colombia decided to profit from the war as well, supplying the Liberals and trying o create yet another state completely dependent on it.

Diego Portales.

Colombian’s greater economy, and the fact that Charkas was also somewhat dependent on it, ensured that the Liberals eventually won and Portales had to flee to Peru. But Charkas was not satisfied. The tension were great, Chile was weak and had no allies, with the exception of Colombia. The benefits from a war could have been potentially enormous, especially if either side managed complete control of the coast. Guano trade had completely boomed, and with Chile in crisis, Peru (or rather, its overlord Colombia) had become very rich. Charkas was not able to exploit its guano, and Chile had not been able until that moment. A swift attack in a Chile that was already down would be enough, it would give Charkas all that profitable guano and eliminate all its problems.

The only thing against the great Charkean plans for glory was Colombia, but the Charkas were willing to bet that, in case of war, the Colombian course of action would be selling weapons to both sides (to Charkas through Peru, to Chile through sea) for maximum profit. Finally, the last Charkean ambition concerned Peru. Santa Cruz had showed interest in a confederation, if only to free Peru from the Colombian yoke. Perhaps by selling that guano Charkas could become strong enough to join Peru, defeat Colombia and become the premier South American power… after all, things weren’t going well in the South Cone after the death of Francia and Colombia was through some difficulties too.

Charkas' future and plans for glory seemed secured once Colombia went through its Grand Crisis and thus Santa Cruz was able to take absolute control of Peru and totally independize it from Colombia. He would go to Charkas, and in a secret treaty, and taking advantage of the Platine War being a distraction for La Plata, he declared the Confederation and started a war against Chile.

A surviving photo of Andres de Santa Cruz.

Chile was disunited and weak, freshly out from a Civil War and, thanks to Peru, cut from anyone who could have supplied it. However, it had a great advantage, and that was that in order to win the war the Peruvo-Charkean alliance had to effectively win, while Chile only had not to lose. Thus, the Chilean Navy adopted a defensive doctrine while the Army moved in order to stop any Charkean offensive that miraculously managed to go through the Atacama Dessert. Meanwhile all of this happened, behind the curtains negotiations and planning were undertaken to transform the pitiful river badges of Chile into a proper fleet.

It is a little sad that all this planning was actually unnecessary, as Peru was utterly and completely unprepared for a war. Colombia had been actively working to keep it weak, and thus the Peruvian army was nonexistent and the Peruvian Navy could have been dispatched easily had the Chilean commanders actually tried to engage in offensive instead of gazing at the enemy in fear. Charkas was unable to do anything in land, and their Navy was the most pitiful, being described by a Colombian observer as something that barely floated.

As for Colombia, the Charkean predictions turned out to be right, and with the British deciding to stay neutral (as per their accords with the French earlier that decade) and the French busy, this left only one country as possible supplier. Colombia sold cheap, but usually low quality weapons to both Charkas and Peru, while also selling them to Chile, all for great profit. It is noted that the Colombian arms, at first knock-outs of British and French models, started to improve in quality and thus became more expensive with time, but by then it was too late and not buying arms would mean leaving their armies unsupplied.

The Confederation and Chile face each other in the battlefield.

By mid-1844 Chile was finally able to conduct operations against the Peruvian Navy, and completely and utterly smashed them in several battles. By mid-1845 Chile was able to establish supply lines and conduct an invasion of Charkas, defeating their army in several battles as well. Chile, following the Prussian traditions and able to buy the better weapons the Colombians had (which were, admittedly, still cheap and bad) looked like the definite winners of the war. In 1846 the Chilean leadership, which was now again a junta of Oligarchs and Military men called the Santafe Boys (they were still educated in London, but their ties were with Colombia), was planning to land in Peru and even take Lima, but an event in Peru changed everything.

In March 14, 1846 the Semi Centennial Revolutions started with the overthrown of Santa Cruz by an association of Liberals who wanted democracy and Liberty. Know only as the Front of Liberty (Frente de la Libertad) and with the blessing of Colombia, who had by this point moved out of its problems, they installed a democratic modern Republic that was, if not a Colombian puppet anymore, a very close ally.

Santa Cruz had to flee to Colombia, as it wouldn't allow the new Peruvian government to execute him but wouldn't indulge his megalomaniac dreams of conquest either. Leaderless and practically already defeated, Charkas collapsed overnight and the Chileans were able to hold a new offensive, capturing their capital, the city of San Andres[4].

The original Chilean plans were to annex the entire Charkean coast (leaving them without a sea access) and a little part of Peru. Instead, and in the Peace of San Andres the map of the are was re-drawn. At the end every party was happy, as Chile obtained all the nitrates and guano and the territories they wanted, Peru didn’t lose that much after all (and had the Chincha island Colombia had taken returned, albeit now with their guano completely exploited) and Charkas, in spite of its almost total defeat still had a little sea access, known as the Charkean Corridor. Charkas was, above all, grateful to Colombia, who it looked up to as some kind of savior, fact helped by the cooperation of the new democratically elected President, Jose Ballivian, with Colombia in industry, economy and international politics.

Peace was restored, and what’s more important to Colombia, all the nations involved ended up heavily in debt with her and dependent in her due to the war, but also, and what's more rare in cases like this one, grateful to her. In the eyes of Chile Colombia was the savior that helped to create a lasting peace, helped to develop the Chilean industry, helped to preserve democracy and helped it to win through the selling of arms. In the eyes of Charkas, Colombia was the savior who prevented the Chilean beast from destroying it, Colombia was the savior that allowed it to retain a sea access and instaured democracy for the first time. Both nations would become Colombian allies ever since.

Map of the changes made by the Treaty of San Andres (1846). Chile annexed most of the territory in dispute, except for a tiny strip given to Charkas so that it could have an access to the sea. That territory, known as the Charkean Corridor, was originally Peruvian, so Charkas also ceded one of its Amazonians territories to Peru.

_________________________________

[1]Yeah, I'm referencing the infamous Chicago Boys of Pinochet here.

[2]Reference to Bismarck and his prediction of WWI.

[3]All this deal with Colombia and Peru will be explained in a future update. Suffice to say that Peru will become the cradle of South American liberty and freedom.

[4]OTL Sucre. As Sucre didn't have anything to do with the Charkean independence, it conserved its colonial name.

To be fair to O'Higgins, he didn't disband the Navy because the threat was over, he did because he had to pay for San Martín's expedition to Peru. Even Cochrane wasn't receiving money. The War of the Peru-Bolivian Confederation paid for a good deal of the debt. 1820-1858. That was how long that debt lasted. One million pounds of the time.

Thanks, O'Higgins.

And Portales was a bit of a visionary. A-Hole on all sides, as evidentiated by his actions and Constanza Nordenflycht. But not wrong. See his thoughts on the Monroe Doctrine and compare them to present day situation.

Portales? Dictator? Yes and no.

Portales was the power behind the power, in this case, General José Joaquín Prieto.

Chilean generals being cautious? Why do I believe Justo Arteaga(1879 General) is already screwing things up?

If you want any Chilean names for the near future, here goes.

Manuel Bulnes, Manuel Baquedano, Antonio Varas, Manuel Montt, José Victorino Lastarria, Manuel Rengifo, Belisario Prats, Anibal Pinto, Domingo Santa María, Juan Williams Rebolledo, José María de la Cruz, Pedro León Gallo, Santiago Amengual and Francisco Bilbao.

Great update, by the way.

Thanks, O'Higgins.

And Portales was a bit of a visionary. A-Hole on all sides, as evidentiated by his actions and Constanza Nordenflycht. But not wrong. See his thoughts on the Monroe Doctrine and compare them to present day situation.

Portales? Dictator? Yes and no.

Portales was the power behind the power, in this case, General José Joaquín Prieto.

Chilean generals being cautious? Why do I believe Justo Arteaga(1879 General) is already screwing things up?

If you want any Chilean names for the near future, here goes.

Manuel Bulnes, Manuel Baquedano, Antonio Varas, Manuel Montt, José Victorino Lastarria, Manuel Rengifo, Belisario Prats, Anibal Pinto, Domingo Santa María, Juan Williams Rebolledo, José María de la Cruz, Pedro León Gallo, Santiago Amengual and Francisco Bilbao.

Great update, by the way.

To be fair to O'Higgins, he didn't disband the Navy because the threat was over, he did because he had to pay for San Martín's expedition to Peru. Even Cochrane wasn't receiving money. The War of the Peru-Bolivian Confederation paid for a good deal of the debt. 1820-1858. That was how long that debt lasted. One million pounds of the time.

Thanks, O'Higgins.

And Portales was a bit of a visionary. A-Hole on all sides, as evidentiated by his actions and Constanza Nordenflycht. But not wrong. See his thoughts on the Monroe Doctrine and compare them to present day situation.

Portales? Dictator? Yes and no.

Portales was the power behind the power, in this case, General José Joaquín Prieto.

Chilean generals being cautious? Why do I believe Justo Arteaga(1879 General) is already screwing things up?

If you want any Chilean names for the near future, here goes.

Manuel Bulnes, Manuel Baquedano, Antonio Varas, Manuel Montt, José Victorino Lastarria, Manuel Rengifo, Belisario Prats, Anibal Pinto, Domingo Santa María, Juan Williams Rebolledo, José María de la Cruz, Pedro León Gallo, Santiago Amengual and Francisco Bilbao.

Great update, by the way.

Thanks, I'm sure all this information will be useful in the next updates.

Does anyone else have any comment or suggestion? Please, even if it's just a "good work", or even liking the post, it does help immensely.

I've finally found it... a TL where Peru us NOT Chile's bitch in a Pacific War between them!

I also see you rolled the Pacific War and the Confederation War into one. Nice.

Overall excellent work. However... it seems that from this agreement, Peru ended up losing Arica and Tarapaca, and Tacna was split to give Chakras/Bolivia access to sea (though I say good for them. Now we won't have jokes here about them being landlocked). I don't know if that was your idea, but none the less, it's good to see Peru not getting the brunt of the war's atrocities as the Chilean army occupies Lima like OTL.

Good update. Can't wait to see what's next in store!

I also see you rolled the Pacific War and the Confederation War into one. Nice.

Overall excellent work. However... it seems that from this agreement, Peru ended up losing Arica and Tarapaca, and Tacna was split to give Chakras/Bolivia access to sea (though I say good for them. Now we won't have jokes here about them being landlocked). I don't know if that was your idea, but none the less, it's good to see Peru not getting the brunt of the war's atrocities as the Chilean army occupies Lima like OTL.

Good update. Can't wait to see what's next in store!

I've finally found it... a TL where Peru us NOT Chile's bitch in a Pacific War between them!

I also see you rolled the Pacific War and the Confederation War into one. Nice.

Overall excellent work. However... it seems that from this agreement, Peru ended up losing Arica and Tarapaca, and Tacna was split to give Chakras/Bolivia access to sea (though I say good for them. Now we won't have jokes here about them being landlocked). I don't know if that was your idea, but none the less, it's good to see Peru not getting the brunt of the war's atrocities as the Chilean army occupies Lima like OTL.

Good update. Can't wait to see what's next in store!

Yeah, rolling those two wars together should prevent futher wars in the future. Peru did lose the war, so that's the reason they lost some territory to Chile and Charkas. This is, in general, a better outcome that OTL's war, as that way TTL's Bolivia still has a little coast and Peru doesn't suffer as much.

Thanks! Nest update is Europe, but after that we'll finally see what everyone's been waiting for! You know what I'm talking about

Anyone else has any comment?

How likely can we see most of Latin America under one country?

Last edited:

How likely can we see most of Latin America under one country?

Not likely, I'm afraid. Distance and resources wouldn't allow it to happen right now (around 1840) and when it finally becomes feasible it will be too late for that. We will probably have a stronger union of Latin America, perhaps even stronger than OTL's EU, but a single, unified country is simple too ASB.

some not So political correcto comenta about the 2016 election and trump infamous mexican tirade.. i think he voted trump.Does anyone knows why was Red Galiray banned?

He's not even in the US. He's in Ecuador.some not So political correcto comenta about the 2016 election and trump infamous mexican tirade.. i think he voted trump.

I just wish he'd appeal to Ian and get back and keep his mouth quiet about that stuff...

some not So political correcto comenta about the 2016 election and trump infamous mexican tirade.. i think he voted trump.

I'm not sure. I know now that he started another thread about how bad Trump would be for Latinamerica. Maybe that was

Threadmarks

View all 76 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 62: The Balkan War Chapter 63: The Liberal Revolution Appendix: The Colombian National Army Appendix: The Colombian Cavalry Appendix: The Colombian Artillery Appendix: The Colombian Navy Chapter 64: From the Andes to the Caribbean Chapter 65: The Irrepressible Conflict- Status

- Not open for further replies.

Share: