Thanks! Sorry the updates take awhile, but I’d rather get out decent and lengthy chapters instead of short and poorly thought-out chapters.Yes! Another update! This timeline just keeps getting better and better.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Man-Made Hell: The History of the Great War and Beyond

- Thread starter ETGalaxy

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 30 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter Twelve: Defend of Die - Part Two Interlude Eleven: Europe Circa November 1929 Interlude Twelve: Scrapped Content Chapter Thirteen: A Bold New World Chapter Fourteen: Growing Storm Clouds Chapter Fifteen: Those Who Escaped Chapter Sixteen: A Twist of Fate Man-Made Hell: The Modern Tragedy Novel ReleaseThank you!Great update!

Also, just to let people know, the one year anniversary of when I first posted Man-Made Hell is on the 23rd, so I’ll try to get something special out for that. I won’t be able to pump out chapter seven that fast, but I should be able to make a graphic and maybe even a trailer on YouTube, although I haven’t used iMovie in a really long time and I wouldn’t be able to use my voice for anything.

I was actually going to introduce an Indian revolution in the latest chapter, but it got too long as it was and I cut that back. The next chapter should be Entente/British Empire focused though, which means that India will get some attention alongside other increasingly unstable colonies.I can imagine that Brittish rule in India is already collapsing

What is the situation in the Balkans? Has Greece folded? How's Romania, since they've been neutral this whole time?

I’ll touch on the Balkans in the next chapter (they really need some attention), but the basic situation right now is that Bulgaria’s doing really well, the Austro-Hungarians are just trying to maintain control over Montenegro and Serbia, Greece is on the brink of collapse and is only staying alive due to Entente support (which is obviously needed elsewhere as of recently), and Romania looks like it’s doing fine, but is on the brink of a massive upheaval. I don’t want to spoil too much, but long story short, the Balkans are a powder keg waiting to explode.What is the situation in the Balkans? Has Greece folded? How's Romania, since they've been neutral this whole time?

Shouldn't this be an increasingly expensive luxury? Unless it's talking about how the the amount of men per mile has been decreasing recently.a war where soldiers were becoming an increasingly affordable luxury

In the short term, this will give the French a good amount of manpower to throw against Germany. In the long term? The demographic shock is going to be catastrophic. Even before that point France in TTL was set up to have bigger demographic problems than OTL. Even if France is ultimately a 'winner' of the war, it will be very phyrric.“I’m no idiot. My army needed more soldiers, and I wasn’t going to let something as trivial as gender get in the way of something as glorious as the liberation of the working class.”

I don't see either Republican OR Red France building up much of their navies. Red france has a manpower crisis and is probably much more focused on holding back Italy and Germany. Algeria France meanwhile has very little industry in the colonies. I can see both sides building small ships and submarines, but nothing with true offensive capability. And the Regina Marina would probably stomp both of them together. (Actually on that note, what did become of the Pre-War French battle fleet?)Communard and Republican forces alike would continue to clash in the Mediterranean Sea for many years to come as the two rival governments built up their navies to prepare for an invasion of the other.

Nice that there's some sort of democracy, but with the ongoing war there is going to be plenty of opportunity to take a loose interpretation of it.there was no need to continue the suspension of the Communard constitution following its expiration in the October of 1924, thus leading to the beginning of the world’s first true communist democracy.

Useful in a spontaneous conflcit like this civil war, but without large-scale coordination the WMA will do very badly against the likes of Germany.while the Red Army gained a reputation for its meticulously crafted efficiency, the Workers’ Model Army gained a reputation for its unpredictable spontaneity.

By the way, what happened to the Royal Navy? Is it mostly on one side of the conflict or is it split?

I hope this doesn't end up with DIRECT RULE FROM LONDON over all Brittania.-Excerpt from the journal of then-Organization for Domestic Security Captain Oswald Mosley, written circa July 1924

Would you ever do a minor update on the status of various ethnic minorities throughout the world? Such as the romani in europe

Yep, that’s a typo on my part. Thanks for pointing that out.Shouldn't this be an increasingly expensive luxury? Unless it's talking about how the the amount of men per mile has been decreasing recently.

Right now, the German strategy is more or less a reverse Schlieffen Plan in which the Heilsreich is focusing almost entirely on the more well equipped and stronger numbered Red Army, so there isn’t really a German offensive the Commune needs to repel yet. In the long term though, you’re right, France’s demographics will really be out of whack, and to be honest it’s something I haven’t thought a lot about yet.In the short term, this will give the French a good amount of manpower to throw against Germany. In the long term? The demographic shock is going to be catastrophic. Even before that point France in TTL was set up to have bigger demographic problems than OTL. Even if France is ultimately a 'winner' of the war, it will be very phyrric.

Good point. I think I’ll make French naval buildup more of a long term project, and it’s suffice to say that an invasion by either the Communards or the Republicans is a long way off. The pre-Great War French navy is probably just partitioned between the Commune and the Republic, although with the French Civil War starting due to military mutinies in the trenches, it’s safe to say the navy is primarily on the side of Foch.I don't see either Republican OR Red France building up much of their navies. Red france has a manpower crisis and is probably much more focused on holding back Italy and Germany. Algeria France meanwhile has very little industry in the colonies. I can see both sides building small ships and submarines, but nothing with true offensive capability. And the Regina Marina would probably stomp both of them together. (Actually on that note, what did become of the Pre-War French battle fleet?)

Oh, like a Woodrow Wilson-esque situation? That could actually be pretty fun to play around with! I do think it would make sense for the French Commune to be a pretty bad place for Entente/Central Powers/Capitalist in general sympathizers, although at the end of the day the Commune will be a democracy (a flawed democracy, but still a democracy) because socialist democracies are always fun to play around with IMO, and I think, or at least I hope, having a centralized Communard democracy revolving around trying to defeat the Central Powers will be interesting.Nice that there's some sort of democracy, but with the ongoing war there is going to be plenty of opportunity to take a loose interpretation of it.

WMA involvement in mainland Europe is still a long way off, but I’ll be sure to make the WMA adapt as it steps foot in France.Useful in a spontaneous conflcit like this civil war, but without large-scale coordination the WMA will do very badly against the likes of Germany.

It’s primarily allied with the Loyalists, although there’s still a sizable portion allied with the WMA.By the way, what happened to the Royal Navy? Is it mostly on one side of the conflict or is it split?

I don’t want to spoil what I have planned for Mosley, but don’t worry, he won’t be a Kaiserreich ripoff, at least not intentionally.I hope this doesn't end up with DIRECT RULE FROM LONDON over all Brittania.

Well thanks!Man this gets better and letter each time I read it

That’s actually an interesting idea. I might, although any minorities that have been in substantially different circumstances thus far have mostly been addressed, such as French Germans. It’s definitely something for me to consider though!Would you ever do a minor update on the status of various ethnic minorities throughout the world? Such as the romani in europe

True. And also, you really should put thoughts into the long-term demographic impacts of this war. Ten years, let alone thirty, of industrialized warfare will kill a lot of military-aged people.France’s demographics will really be out of whack, and to be honest it’s something I haven’t thought a lot about yet.

I mean, unless the various nations involved in the conflict happen to embrace polygamy after the war is over, keeping women out of the military won't actually help when the demographic crunch comes knocking years down the line.In the short term, this will give the French a good amount of manpower to throw against Germany. In the long term? The demographic shock is going to be catastrophic. Even before that point France in TTL was set up to have bigger demographic problems than OTL. Even if France is ultimately a 'winner' of the war, it will be very phyrric.

It would be interesting to see how the romani people react to the war in Europe

They could actually be really interesting due to being dispersed across several European nations.It would be interesting to see how the romani people react to the war in Europe

Countryball Map of Europe Circa December 1924

Hello everyone! Today marks the one year anniversary since I first posted Man-Made Hell, which absolutely blows my mind! In order to celebrate, I decided to make a map of MMH's Europe as of December 1924, but to make things more interesting I added countryballs.

The image was too large, so you can find it here instead

And this image is also too large, so you can find it here instead

The image was too large, so you can find it here instead

here’s the base map without countryballs, which I think turned out pretty good color and border-wise, so I may use it again.

And this image is also too large, so you can find it here instead

Anyway, thank you so much for following Man-Made Hell during this last year! The support this TL got astounded me and it's always amazing whenever someone compliments this weird little passion project of mine. Hopefully you're all looking forward to the next few chapters, because here's to another great year for Man-Made Hell!

When will the next update come?Hello everyone! Today marks the one year anniversary since I first posted Man-Made Hell, which absolutely blows my mind! In order to celebrate, I decided to make a map of MMH's Europe as of December 1924, but to make things more interesting I added countryballs.

The image was too large, so you can find it here instead

here’s the base map without countryballs, which I think turned out pretty good color and border-wise, so I may use it again.

And this image is also too large, so you can find it here instead

Anyway, thank you so much for following Man-Made Hell during this last year! The support this TL got astounded me and it's always amazing whenever someone compliments this weird little passion project of mine. Hopefully you're all looking forward to the next few chapters, because here's to another great year for Man-Made Hell!

I’m working on a chapter for my other TL, Dreams of Liberty, right now. Chapter Seven should come out sometime in late August, assuming school starting up doesn’t get in the way.When will the next update come?

Chapter Seven: The Setting Sun

Chapter VII: The Setting Sun

“Now they want me - now they want us - to leave Europe. Maybe forever.”

-King George V in a private conversation with Mary of Teck, circa December 1924.

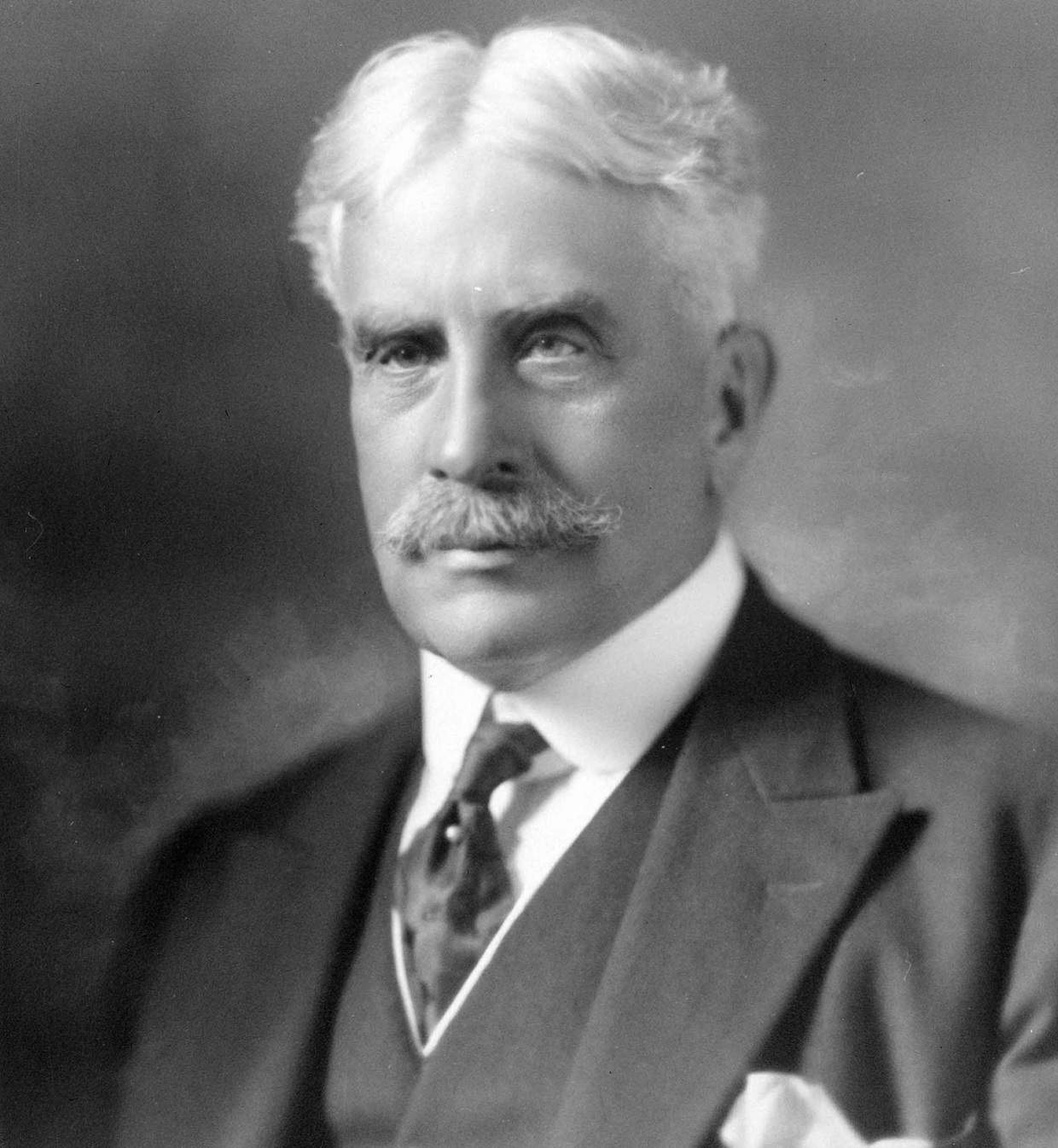

King George V of the United Kingdom.

Halifax, Canada, circa January 5th, 1925:

As a large ship sailed towards the city, a crowd of civilians, reporters, and even political officials gathered alike awaiting its arrival. As this ship got closer and closer and the Union Jack could be made out in the distance, camera crews got into their positions while reporters scrambled to get as close as possible to where the important passengers of this ship would step foot into Canada. A few more minutes passed, and soon enough the ship had docked into the crowded Halifax harbor. Once a gangplank was set up, out stepped none other than King George V of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and the British Dominions, a living symbol of the nation that had ruled the world for over a century. Dressed in a coat suited for the cruel Canadian winter, His Majesty was accompanied by the Queen Consort, Mary of Teck, and was followed by his children, including the eccentric Prince Edward, who was notably the only aristocrat entering Canada who visibly smiled and gave the crowd held back by a crude fence the attention they craved.

Bearing a sleek top hat, King George V made use of the rim of his head attire by avoiding looking at the crowd his eldest child happily entertained. The people of Halifax cheered for their king, although the clapping was relatively unenthusiastic and was more sympathetic to the attitude all who bowed to the British Empire had been overcome with since the beginning of Phase Two of the Great War. Sure, “God save the King!” could always be heard from the crowd, but its tone was generally less jubilant than usual, and it was accompanied by “the Empire stands with Great Britain!” and “the House of Windsor will never fall!” Anyone at the harbor could feel this somber atmosphere, and a handful of years later King Edward VIII would describe the welcoming crowd in Halifax as “a funeral for a dead nation.”

Before entering an elegant automobile decorated with the Royal Standard of the United Kingdom, King George V would approach Canadian Prime Minister Robert Borden, who went through a traditional and well-rehearsed greeting to the sovereign of what was still, at the end of the day, the largest empire in the world. As the two men exchanged greetings, George V revealed a faint smile to the Prime Minister, all the while understanding that it would be the Canadian government rather than its British counterpart that His Majesty would primarily be working with from now on.

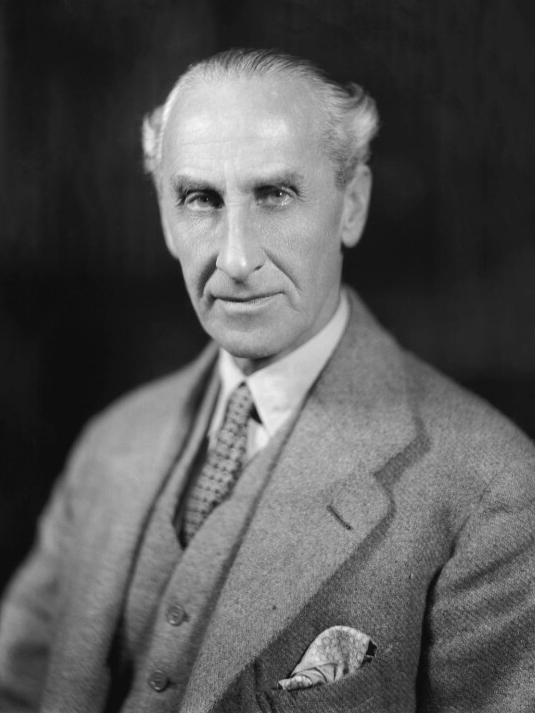

Prime Minister Robert Borden of Canada.

After a brief exchange, Sir Borden and the Windsor family would go their separate ways as King George V and his wife stepped into the vehicle waiting in front of them, while their children entered the automobiles lined up behind. Still keen on avoiding making any eye contact with his audience of politicians, press, and civilians alike, George V opted to sit on the left side of the automobile, which for the time was facing away from the public, while Mary of Teck had to deal with the flashing lights of cameras and the slew of questions from reporters from every corner of Canada and even a handful of foreign journalists, especially those visiting from the United States.

“Where will His Majesty reside while in Canada?”

“How long is the exile from Europe supposed to last?”

“Is the elected British government expected to go into exile?”

“What is His Majesty’s reaction to the recent socialist insurgencies in the Indian Empire?”

“How will the fall of the United Kingdom affect the sovereignty of Canada?”

The Queen Consort did not dare to acknowledge the legion of journalists. Without even a hint of emotion, all she did was stare down at her dress, ensuring that not even a subtle gesture could be interpreted as a response to be jotted down for a national headline. But after a few minutes into their drive from the harbor, both George and Mary began to peek out of the windows of their automobiles. Sooner or later, the two would have to become accustomed to these Canadian reporters and heed to their interrogations.

After all, as long as the House of Windsor was in exile, Canada would be His Majesty’s homeland.

I Used to Rule the World

“Let it be known to those who wish to see the British Empire fall, be they communist or fascist, revolutionary or reactionary: You will fail. Our Empire has stood for centuries, and as long as the people of Great Britain continue the fight for King and Country, it will stand for centuries more.”

-Excerpt from Prime Minister David Lloyd George’s resignation speech, circa May 1924.

The city of Edinburgh, circa July 1924.

By suppressing disgruntled trade unionists the United Kingdom had inadvertently created the Workers’ Commonwealth, which posed an existential threat to the British establishment the likes of which had not been faced since the days of Oliver Cromwell and the English Civil War. In every war the English, and later the British, had since engaged in the top enemy had always been external, but with a few poor decisions the United Kingdom had turned its involvement in the Great War from a clash against foreign revolutionaries and the power-hungry Central Powers into a war for the very survival of the heart of the British Empire itself. There could be no white peace with the Workers’ Commonwealth, no colonial cession, and no war reparations. Either the United Kingdom would survive or it would be replaced by the Workers’ Commonwealth.

While many Loyalists had anticipated a short suppression of the upstart socialist rebels, the guerrilla tactics of the Workers’ Model Army and widespread discontent throughout United Kingdom split the island of Great Britain in half, with the Workers’ Commonwealth getting the more populous and urbanized southern half. While parades in the name of Karl Marx and Daniel De Leon covered the streets of 1920s London, the Union Jack still waved high in Edinburgh, which had become the makeshift home of the British government and crown in the aftermath of the takeover of southern England by socialist rebels. While many Scottish trade unionists had initially supported the Workers’ Commonwealth and had taken up arms against their capitalist oppressors (including the infamous John Maclean), the Loyalists had long since crushed socialist insurgencies in Scotland and had turned the hills of Alba into a fortress for those loyal to His Majesty.

Of course, presiding over the beginning of a revolution fails to do much good for any leader. As the riots in southern England escalated into a full-blown civil war, much of the blame fell on Prime Minister David Lloyd George. The remaining leftist Loyalists deemed the prime minister a stubborn tyrant while conservatives claimed that David Lloyd George had not gone far enough in the face of what could very well be the beginning of the end of the United Kingdom. Prime Minister Lloyd George did take some action to contain the spread of the Workers’ Commonwealth, such as the redistribution of soldiers deployed on the battlefields of the European mainland to the frontlines of the Second Glorious Revolution (or the British Civil War, as the Loyalists called it) almost immediately after the declaration of the Workers’ Commonwealth as well as the banning of trade unions and organizations affiliated with Inkpin’s revolutionary government, but this ultimately did not weaken, let alone defeat, the Workers’ Model Army.

As the British Army was defeated time and time again by the militias of the proletariat, the Wartime Coalition government that had existed since David Lloyd George’s assumption of power from Herbert Henry Asquith in 1916 began to turn on the prime minister, who was proving to be incapable of dealing with the crisis at hand. The fall of Wales in the May of 1924 would be the last straw for a disgruntled government, which forced David Lloyd George to resign on May 23rd, 1924. Lloyd George was succeeded by his First Lord of the Admiralty, the Earl of Lytton, who had become renowned within the Wartime Coalition during the British Civil War for his skillful handling of the Royal Navy. A member of the Conservative Party, the Earl of Lytton was one of the voices within Cabinet that had advocated for a stricter wartime government to ensure the defeat of the Workers’ Commonwealth and was keen on implementing these policies as soon as he became the British head of government. Democracy was not to get in the way of the Lytton ministry.

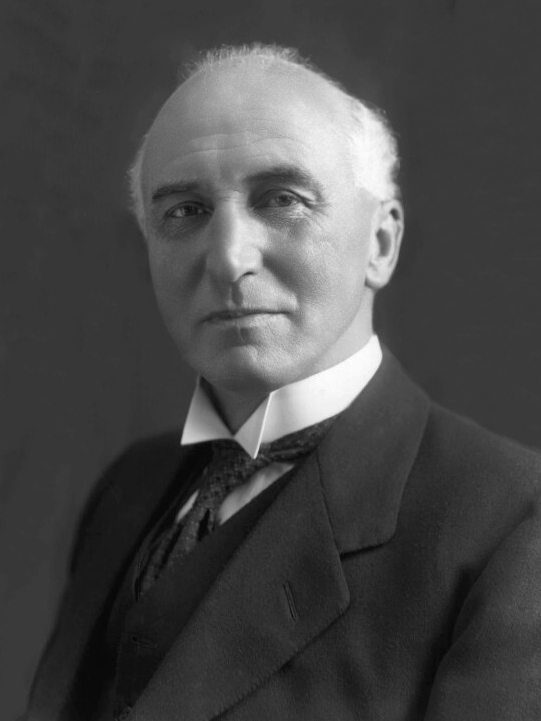

Prime Minister Victor Bulwer-Lytton, 2nd Earl of Lyton, of the United Kingdom.

Upon assuming control of what remained of the United Kingdom, the Earl of Lytton immediately got to work asserting his authority upon the Wartime Coalition in an attempt to bring back the British Empire from the brink of destruction. Prime Minister Lytton called upon the leaders of the Wartime Coalition to promise that no vote of no confidence or any other traditional parliamentary activities that would distract from the war effort would occur until the British Civil War was over, and the vast majority of Parliament submitted to Lytton’s demands, although HH Asquith, now the Leader of His Majesty’s Most Loyal Opposition, would openly protest the increasing authoritarianism of the Wartime Coalition. In order to further crush any potential opposition to his campaign of warfare, Prime Minister Lytton would use his now-unrivaled reign over the Wartime Coalition and therefore Parliament to pass the Suspension Act on June 25th, 1924, which, simply put, prohibited any parliamentary elections until the end of the British Civil War.

The Suspension Act obviously garnered controversy, but the supremacy of the Wartime Coalition meant that any opposition to the Earl of Lytton, whose grip on Parliament essentially turned him into the de facto dictator of the United Kingdom, was pointless. Throughout the summer of 1924, every single Briton could feel the effects of the Lytton ministry. Wartime media censorship was substantially increased to the point that no Loyalist could read a single article critical of the British government without fearing the law and fervent nationalism was encouraged in every city. Of course, all Loyalists were aware that the United Kingdom was losing the war, even if vague newspapers paid little attention to the victories of John Maclean. The influx of refugees from northern England alone was enough of an indication of the situation of the British Civil War, and as rumors spread the Summer Offensive became known to every single Briton, be they Loyalist or revolutionary.

While the Summer Offensive could not be stopped and inevitably was an embarrassment for the Lytton ministry, the fall of 1924 did bring better success. Military reforms would ultimately save Scotland from an invasion for the time being, and the end to the continued retreat of the British Army gave the Loyalists at least a bit more time to recruit more soldiers (many of which were simply sent to Europe via conscription in British dominions) and fill up depleted armories. The officers that had let the revolution sweep across Northumbria were ordered to step down and were replaced with new commanders, most notably General Winston Churchill, who had earned notoriety in Hejaz’s fight for independence as the slayer of the Lion of Arabia. General Churchill became the field marshal of all Loyalist forces in Great Britain in the September of 1924 and would successfully hold back the Workers’ Commonwealth in a war of attrition that lasted well throughout the subsequent fall season.

General Winston Churchill of the British Army.

As the former First Lord of the Admiralty, Prime Minister Victor Bulwer-Lytton made sure to use the Royal Navy to the best of his abilities and ensure that, even in her darkest hour, Britannia would still rule the waves. The policy against combatting German ships more or less remained consistent with the naval war of attrition that the Earl of Lytton had presided over during his time in the Lloyd George ministry. With that being said, the naval presence in the stagnant war against Germany did slightly decrease to match the similar naval redistribution conducted by the Kriegsmarine ever since the beginning of Phase Two. After all, both the United Kingdom and the Heilsreich had bigger priorities than each other. Why waste resources in what had by then become a meaningless arms race in the North Sea?

As the Kriegsmarine shifted its attention to the war in the Baltic Sea against the Soviet blockade in the region, the Royal Navy was deployed around southern England, most notably in the English Channel that was often traversed by the French Commune, in an attempt to starve off the Workers’ Commonwealth. In a cruel reverse of fate, the Royal Navy went from the force defending England from the blockade of the German Empire all those years ago to the force encircling England with a blockade of its own. The vast majority of the Royal Navy had actually remained loyal to the Crown as the rest of Great Britain was torn apart (up until the March of 1924, the Royal Navy had actually remained the largest naval force in the world before being overtaken by the German Kriegsmarine), and so the waters of western Europe were still the domain of the British Empire and the blockade around England was relatively easy to enforce, but the Royal Navy had little effect on the war back on land. The Workers’ Commonwealth was no autarky, but at the end of the day it did ultimately have immediate access to more resources than the rump United Kingdom and aerial missions across the English Channel alleviated some of the pain inflicted by the Loyalist blockade.

As the frontlines of the British Civil War remained stagnant throughout a bloody fall, the clash between monarchist and revolutionary would, at least for a time, revolve around an arms race for aerial dominance. The United Kingdom already had its own air force in the form of the Royal Air Force (RAF), which had existed since the April of 1918, but the Workers’ Commonwealth had to forge its own fleet of aircraft from the ground up. Under the command of Comrade Protector Albert Inkpin himself, the Workers’ Democratic Air Force (WDAF) was established very early on into the Second Glorious Revolution, and was formed in the May of 1922, therefore predating even the Workers’ Model Army.

Initially little more than a collection of airplanes captured by trade unionists from the RAF, the WDAF was far more centralized than its counterparts on land and sea. Planes were not as accessible as guns or even ships, so militias never really formed as a predecessor to any Commonwealth air force. Instead, the United People’s Congress voted to seize all aircraft and form the Workers’ Democratic Air Force as the first fully-fledged branch of the Commonwealth armed forces. To appease the calls for a decentralized air force, the WDAF was, as the name implied, democratic, with the premier of the WDAF and a handful of other high-ranking officer positions being elected by air force members either every three months or by a vote of no confidence by a majority of squadrons.

The WDAF was initially underfunded in comparison to the army and navy of the Workers’ Commonwealth. After all, the Commonwealth’s military strategy revolved almost entirely around spontaneous guerrilla warfare, a tactic the WDAF did not mix well with, not to mention aircraft was relatively expensive to produce and was usually not considered worth the investment by the United People’s Congress. The Royal Air Force, on the other hand, was kept in much better shape than its revolutionary counterpart and would often go on bombing runs in the early years of the British Civil War, although as the infrastructure of the United Kingdom was seized these bombing runs became more and more risky. Nonetheless, the RAF would be a valuable asset of the Loyalists and was able to keep up with the technological progress adopted by the more stable powers of continental Europe, even in a state of civil war. As the Heilsreich began to utilize radial engines for their airplanes, the United Kingdom followed suit, and by the March of 1924 rotary engines had become obsolete.

A Bristol Bulldog fighter plane of the Royal Air Force, circa August 1924.

As the British Civil War grinded to a standstill, the war in the sky would become as important as the war on land and sea. The stagnant war of attrition turned bombing raids from above into the only way to competently wipe out large swaths of enemy infrastructure and resources, and soon enough air raid sirens were commonplace throughout all of England. The Workers’ Commonwealth was able to hold back the much larger RAF with the underfunded WDAF and whatever anti-aircraft weapons could be found, but the Commonwealth was clearly behind its monarchist counterpart when it came to the war raging amongst the clouds. In the September of 1924, the UPC heavily increased WDAF funding to invest in a new slew of aircraft. By the October of 1924, the numbers of the WDAF were approximately equal to that of the RAF following a rapid buildup of admittedly outdated airplanes. By the December of 1924, the WDAF’s fleet primarily consisted of radial engine airplanes and Scotland feared air raids as much as England.

As bombs began to fall around Edinburgh, the makeshift capital of the United Kingdom and temporary residence of the House of Windsor, it became clear that no corner of Great Britain was safe from the scourge of the British Civil War. The government of the United Kingdom was no longer safe from the weapons of war, and while Parliament could afford staying in Great Britain for the time, the death of the royal family at the hands of the bomb of a revolutionary simply could not be risked, especially in such a dark time. Therefore, under pressure from Prime Minister Victor Bulwer-Lytton (and, due to the autocratic nature of the Lytton ministry, by extent Cabinet), King George V was asked to flee Great Britain and head for Canada for an unspecified amount of time. After consulting with his family, His Majesty agreed to leave Great Britain once the new year began, and the House of Windsor would begin its exile in Canada upon arriving in Halifax on January 5th, 1925.

Just after the Windsors arrived in Canada, the British Civil War would begin to move yet again, and just like in the prior summer, the tides of the war were not in favor of the Loyalists. On January 9th, General Winston Churchill was severely injured by an artillery shell, and while he would ultimately survive, the famed general would have to be away from the British Civil War as he recovered. In the meantime, General William Marshall, a veteran of the British invasion of Mesopotamia, took over control of the Loyalist army in the British Civil War, but this would prove to be a fatal mistake. General Marshall, while once a highly regarded commander back in Phase One, had since become a tired armchair general who had wished to retire in 1923 but would remain in the British Army in the fight against the Workers’ Commonwealth due to pressure from both Cabinet and his fellow officers.

While William Marshall had been a decent enough commander under the leadership of Churchill and had fared better than most during the Summer Offensive, his success commanding over smaller units of soldiers in a war of attrition did not translate over well to presiding over an entire war. On January 23rd, 1925 the WMA took advantage of an opening at Longtown and in a matter of days would cross over into Scotland. Marshall’s defensive strategy of barely falling back, while manageable on a smaller scale, was ineffective when applied to the entirety of Loyalist forces in the British Civil War, which was gradually pushed back by constant guerrilla tactics. By the beginning of the March of 1924, the Workers’ Model Army had conquered Moffat and Edinburgh would soon inevitably become a battlefield.

The Loyalist war effort across the Irish Sea was not any better. After a successful December, the Socialist Republic of Ireland was on the brink of waving its emerald banner over Belfast and Loyalists to the north were becoming both undersupplied and demoralized. The Irish Democratic Army would make one last push into Ulster as the winter thawed away and the spring of 1925 was ushered in. British Army defenses in Ulster would disintegrate in the face of LT tanks bearing the Celtic harp, and city after city would fall to the Crimson Emerald. Armagh fell on March 2nd, Lurgan fell on March 14th, and Belfast fell on March 26th. As a banner of green arose from the ashes of the fallen temple of Irish Loyalism, it became apparent that the Irish Revolutionary War was over. A handful of Loyalist pockets still fought for King and Country in the northern reaches of Ireland, but evacuations to Scotland were already underway.

As the Socialist Republic of Ireland began to rebuild from its war for independence (the Great War was not, however, done for Ireland; not long after the Battle of Belfast the Irish Democratic Army was deployed in France), the WMA was also on the brink of banishing capitalism from Great Britain. Loyalist casualties were stacking up, while the production of equipment and recruitment of soldiers within the Workers’ Commonwealth was accelerating at a rate the remnant of the United Kingdom could not keep up with. John Maclean and the SLA would conquer Glasgow on April 3rd, 1925 and would go onto push into northern Scotland while the majority of WMA regiments set their sights on Edinburgh. As April came to an end, so too would the United Kingdom’s reign in Europe. By the time the WMA approached Edinburgh, the Scottish Highlands were under the control of the Workers’ Commonwealth, and so once the capital of Scotland fell to the proletariat, Parliament would have nowhere to run except Canada. Seeing the writing on the wall, Prime Minister Lytton ordered the evacuation of the British government to Canada on April 20th, and only a few days later the Battle of Edinburgh would commence. Few Loyalist soldiers stayed around to see Edinburgh fall, but the final victory of the Workers’ Commonwealth over the United Kingdom on April 24th, 1925 was a momentous occasion nonetheless.

Great Britain had, just like Ireland, France, and Russia before it, been consumed by the revolutionary flames of the proletariat.

Darkest Hour

“Great Britain falls to the Third International”

-New York Times headline, circa April 25th, 1925.

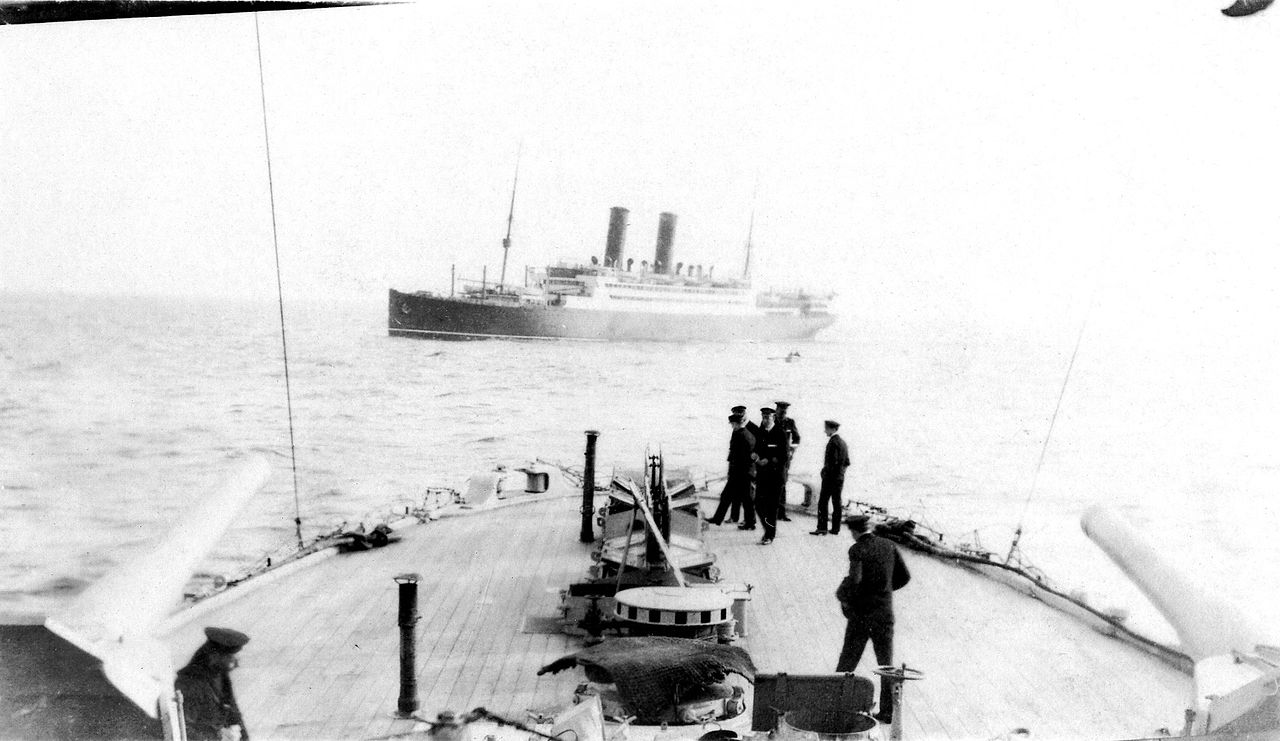

A Canadian warship stops a British ocean liner evacuating Europe for inspection in the Atlantic Ocean, circa March 1925.

After centuries of being ruled by a monarchy, Great Britain, which had been the ruler of the world only a decade ago, had become the domain of a new revolutionary state. Where the Entente had once stood against the wrath of Germany, the Third International had taken its place. Veterans of the revolutions in Great Britain and Ireland became foot-soldiers in the trenches of France while British privateers clashed with the Heilsreich in the waters of the North Sea. In Europe, only a few strongholds of the Entente still remained, and even then one of these temples, Greece, was almost guaranteed to soon become yet another occupation zone of the Central Powers in the defeated Balkans. Europe was no longer the continent of aristocratic imperialists, it was the continent of revolutionaries and reactionaries, locked in a seemingly endless struggle for all they surveyed.

But beyond the reaches of Europe, the Entente still fought against both communist and fascist alike. In a cruel twist of fate, the colonies of the empires that had been built up by the titans of Europe over centuries were now hearts of the British and French empires who focused all resources on a conquest of their lost European territory. The French Fourth Republic reigned from Algiers, still barely holding onto its colonies, while the British Empire found itself bowing to Canada, where King George V resided in Rideau Hall and the British Cabinet-in-Exile operated only a few blocks away in Ottawa. It was in Canada where the shards of the United Kingdom were stored whilst the still united and functioning Canadian government did its best to try and assume some form of leadership over the largest empire to ever span the globe.

Unlike the French government, which simply fled to its colonies when cosmopolitan France completely fell to the Commune, the British government did not flee to one of its countless dependencies, and instead evacuated to Canada. A dominion of the British crown, Canada was not a fully fledged independent nation and had to adhere to a handful of British dictates, especially in regards to foreign policy, but Canada was nonetheless far more sovereign than any colony could ever be and was as autonomous as Australia, New Zealand, Newfoundland, and South Africa. When the time came for the British Cabinet to flee Edinburgh, Canada was the most obvious destination. As a dominion, Canada already had its own functioning government that could collaborate with the United Kingdom-in-Exile and would be more stable than any oppressed colony. With the exception of Newfoundland, Canada also happened to be the closest British dominion to Europe, which meant that preparations for a return to Great Britain could be relatively easily conducted from Ottawa.

The relationship between Lytton’s exiled regime and the government of Canada did produce an interesting dynamic between the two organizations. The balance between these forces was completely thrown off by the exile of the Lytton ministry, with the first example of this shift in power being the cession of all Loyalist aerial forces to Canada on May 9th, 1925, therefore handing over the entirety of the Royal Air Force to the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF). While neither the British Army nor Royal Navy were completely dissolved by Canada, numerous regiments and ships were handed over to their Canadian counterparts in order to ensure that the primary fighting force against the Third International and the Central Powers would be under the control of an actual nation. The remnants of the British armed forces primarily operated in domestic colonial affairs, and with the exception of forces in Egypt, the military of the United Kingdom-in-Exile would never really engage with rival belligerents in the Great War. Even the United Kingdom-in-Exile’s grip over its own colonies, the last truly dependent holdings under the Union Jack, would begin to loosen when Canada was given control over all British colonial armed forces and foreign in the New World via the Treaty of Toronto, which was signed on May 24th, 1925.

This Canadian ascendance within the inner machine of the British Empire was the brainchild of none other than Canadian Prime Minister Robert Borden himself. By the time of the Battle of Edinburgh, the Borden ministry was approaching his fourteenth anniversary within a few months, having begun in the pre-war October of 1911. Elected in a time when Pax Britannica still ruled the globe, Robert Borden’s administration was defined by British Imperial involvement in the Great War, the scourge of the 20th Century. However, while the Great War may have been a curse for the United Kingdom and the world in general, it was arguably very well a blessing in disguise for Canada. Most notably, it would be during the Great War that a Canadian army independent of its British counterpart was forged.

If the Great War had ended prior to the beginning of the Second Glorious Revolution, it is likely that Canada would have emerged on the other side of this alternate and weaker inferno only slightly less dependent on the British. But the Great War, of course, did not end in this forgotten time and the inferno would instead continue to burn for many decades, and the inferno would burn the United Kingdom alive. As the head of the British Empire was sliced off by the hammer and sickle, the pieces of the shattered realm of Windsor were picked up and stitched together into a Frankenstein’s Monster, this time with two heads. One of these heads was the exiled Lytton ministry, which hung onto its authority by a thread via the colonies, while the other head was Canada. And under the rule of Robert Borden, where there had once been two heads there would soon be one.

Insistent that the British Empire must recentralize under one leader rather than two squabbling governments, Prime Minister Borden would lead efforts to shift power away from Lytton, which was especially easy thanks to the monopoly of authority he held over the Canadian parliament via the Unionist Party. It would be Borden who had promoted the redistribution of British military forces and the Treaty of Toronto had been approved due to Borden’s encouragement of turning all corners of the New World that bowed to the Union Jack into a united war machine fighting against all shades of the crimson of the Third International. But Robert Borden’s gambit for Imperial domination was far from over, and public support was turning in his favor. As the British Empire took commands from two heads, management of what was still the largest empire in the world became increasingly inefficient and the Canadian people grew tired of taking orders from the United Kingdom-in-Exile. Canadian public support for the plight of the British Empire and the Crown were higher than ever before, but support for the exiled Lytton ministry was plummeting by the day.

As the Great War raged on in the Atlantic Ocean and spring turned into summer, Robert Borden prepared for the rise of a new British Empire that would be ruled in his own government’s name. By the beginning of June, Victor Bulwer-Lytton could barely stroll through Ottawa without attracting jeers from disgruntled Canadians, for the downfall of his reign was all but guaranteed by this point. The Borden ministry would make its ultimate push for power in the fateful June of 1925, but like the ascendancy of Canada since the Battle of Edinburgh, this push was gradual. First, Robert Borden butted heads with Lytton when he called for the end of the Lytton dictatorship via a general election within parliament of the United Kingdom-in-Exile, with the hope being that John Simon’s Liberal Party would win a majority of seats and pursue a policy of protection under Ottawa.

With an endorsement from both the Unionist Party and Liberal Party of Canada, the Liberal Party would form the new exiled British government after all eligible to vote (Britons residing in Canada were permitted to vote for what remained of the House of Commons) and would assume power on June 11th, 1925. John Simon would succeed the 2nd Earl of Lytton as the prime minister of the United Kingdom-in-Exile, and as a supporter of the re-centralization of the British Empire (in part due to personal ideological positions, such as strongly valuing the economic and colonial stability of the Empire, and in part due to the influence of the Unionist Party), John Simon would be much more open to ceding power to Canada. On June 18th, 1925 the Simon ministry would oversee the ratification of the Treaty of Halifax, which would cede all British colonies in the New World, which had already been under de facto Canadian protectorate status since the Treaty of Ottawa, to Canada as territories.

Prime Minister John Simon of the United Kingdom-in-Exile.

As Canada transitioned into its newfound position as the uncontested guardian of the British Empire in the Americas, the armed forces of what remained of the United Kingdom continued to be redistributed to their Canadian counterparts, which would in turn lead to increased Canadian authority over the entirety of the British Empire. At least in the case of the Atlantic and the Mediterranean, the ships defending the holdings of the House of Windsor no longer bore the Union Jack. Instead, these colonies would watch from the shore as ships waved banners in which the symbol of the United Kingdom was reserved to canton of the Red Ensign of Canada. All the while, the negotiations that would ultimately assert Canada atop the throne of the British Empire would take place throughout Ottawa, ultimately culminating in the passage of the Imperial Protection Act on June 30th, 1925. With the simple stroke of the pen of John Simon, the Imperial Protection Act was put into effect, thus turning the United Kingdom-in-Exile into a protectorate of Canada (renamed to the Kingdom of Canada a handful of days later). Under the mandate of the Imperial Protection Act, the United Kingdom-in-Exile would cede control over its militaristic, economic, and foreign policies to Ottawa, and all policies towards British dominions would also be handed over to the Canadian government.

The Empire of the House of Windsor was reborn, but not back in its European homeland. Instead, the roles of ruler and subject had been swapped and what had once been the British Empire kneeled before the Kingdom of Canada.

Under the reign of what was often nicknamed the Canadian Empire, the Loyalist war effort would accelerate as warships attempted to crawl back to Great Britain. The war for the Atlantic would become more and more of a challenge as the Workers’ Commonwealth built up its own naval power, thus turning Great Britain into the guardian of socialism at the sea, but wartime production would accelerate throughout the Canadian Empire and conscription in every corner of the Windsors’ realms still fighting in the Great War would ensure a steady flow of soldiers and factory-workers alike. The Saint Lawrence River would become a shipyard, where what had once been the mightiest navy to ever sail the seas carried on.

The Canadian Empire was, however, short-lived, not because it was defeated, but rather because it was succeeded by an even greater heir to the British Empire. West of Quebec was the Dominion of Newfoundland, once a sparsely populated dependency of the United Kingdom that had been established in 1907 and, just like all other British dominions, would answer to Canada following the passage of the Imperial Protection Act. With an economy dependent on the exportation of fish, paper, and minerals, Newfoundland would fare decently during the Great War and would be able to sell its main exports to the increasingly hungry United Kingdom once the British Civil War began. Resources would flow from Newfoundland and the riches of the United Kingdom would flow back in return in a steady cycle.

Of course, this cycle of exchange between Newfoundland and Great Britain could not last forever. In the April of 1925 the last Loyalist holdout upon the British Isles would fall to the Workers’ Model Army, and it would not be long the economy of Newfoundland felt the effects of losing its dominant market. The entirety of the British Empire felt a slight economic downturn in the aftermath of the Battle of Edinburgh, but it was Newfoundland, which had almost entirely structured its wartime economy around the needs of Great Britain that was hit the hardest. The Newfoundland Recession of 1925, on top of a government still recovering from instability generated by the corruption of Prime Minister Richard Squires, spelled disaster for the Warren ministry of Newfoundland.

The Recession of 1925 would provide an opportunity to the Borden ministry, one that could kill two birds with one stone. In its moment of great instability, Newfoundland could easily be annexed into Canada peacefully, thus asserting even greater Canadian authority in the New World. While the annexation of Newfoundland could simply be just that, the annexation of the Dominion into Canada as yet another province, the unification of the two nations into a new state altogether would be far more beneficial for the Kingdom of Canada. If Canada and Newfoundland were to unite into one, an opportunity could be opened to invite the governments of recently-formed directly Canadian colonies in the Americas, which were still uneasy about their new rulers in Ottawa, to participate in the formation of a new state that could represent colonial interests, or at least appease them.

And so, in the July of 1925 the representatives of the governments of Canada, Newfoundland, and the former’s colonies all arrived in Halifax to forge a new nation to succeed the British Empire, a nation that would come to be known as the Empire of America. While the Empire of America’s political structure was ultimately not that much different from that of Canada, the Empire would be separated into a collection of kingdoms, with these kingdoms being Canada, Newfoundland, the Bahamas, the West Indies, Guyana, and, interestingly enough, Quebec. While the constituent kingdoms of the Empire of America were more or less powerless and had little political distinction from the Imperial government with the exception of a few minor political benefits (the Kingdom of Quebec, for example, was the only region of the Empire of America that recognized French as an official language alongside English), it did offer some recognition of regional differences within the vast Empire.

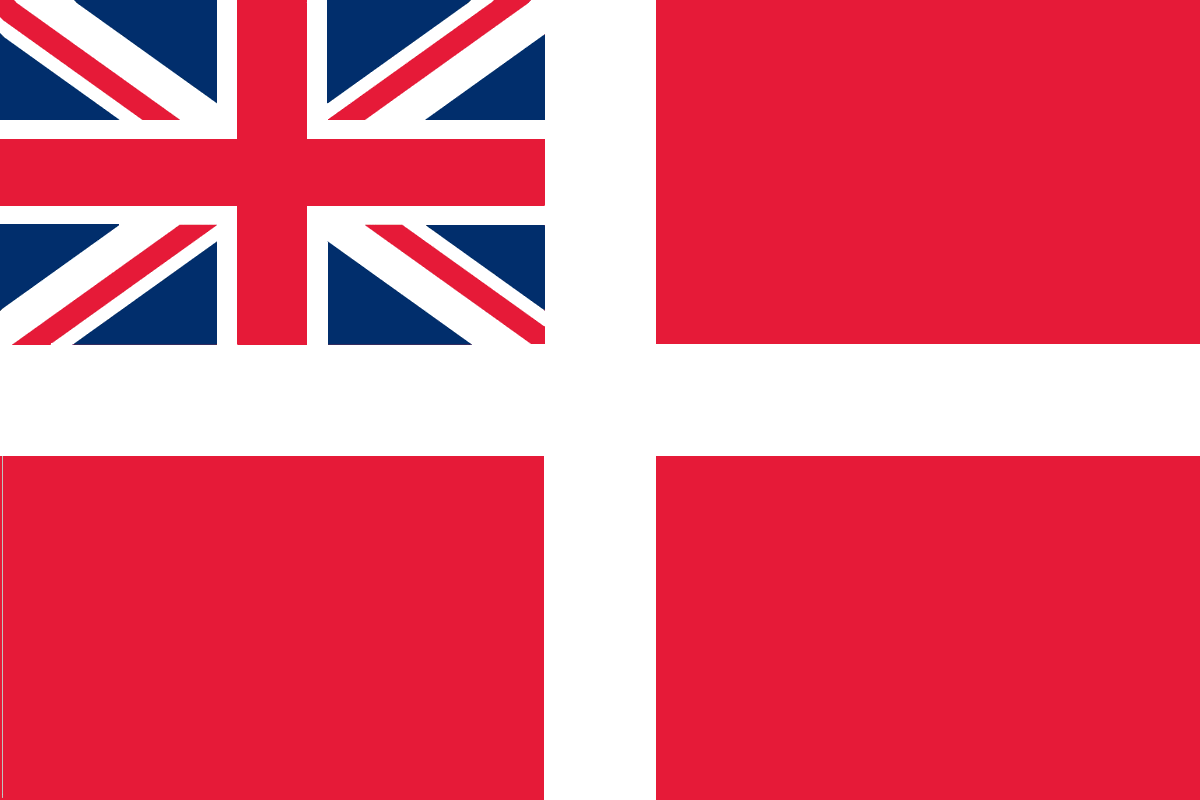

Flag of the Empire of America.

But the far more important feature of the constitution of the Empire of America was the establishment of new constituencies and provinces within every kingdom. Constituencies representing voters would span from British Columbia to Guyana, thus ensuring the total assimilation of the Caribbean into the Empire. Furthermore, the autonomy of the provinces of the Empire of America was increased from that of the provinces of the Kingdom of Canada, with agricultural, fishing, and pension laws being handed over completely over to provincial governments in accordance to the constitution of the Empire of America. Provinces also had the right to implement poll taxes, an addition promoted by representatives of the ruling class of the West Indies, who were remnants of the powerful colonial elite of the days of Pax Britannica and were keen on preserving their grip on power. Poll taxes would be used by the majority of Imperial provinces to disenfranchise the lower class, not only to secure power, but to suppress any movement by the working class to push Imperial politics to the left, which, at least in the eyes of the Imperial bourgeoisie, could potentially sabotage the war effort against the Third International.

After the constitution of the Empire of America was ratified on August 1st, 1925 the first elections of the Empire would occur only two weeks later on August 15th. Nearly all participating parties were previously national organizations-turned local, none of which really had any time to expand their outreach to the greater regions of the Empire of America. The exception to this rule was the Unionist Party of Robert Borden, which would use its authority across all land loyal to the Kingdom of Canada to promote a new slew of Unionist politicians in the West Indies and Newfoundland. After winning a landslide victory in the Imperial Parliament, the Unionist Party would form the first government of the Empire of America on August 19th, 1925 and Robert Borden would officially become the Imperial prime minister. The originally Canadian Liberal Party would form the Official Opposition with an assortment of center-left political parties and would strengthen itself by merging with the Liberal Party of Newfoundland a handful of days later, but even after the unification of the twin Liberial Parties the Unionist Party remained the unstoppable ruler of the Empire of America.

And so the Canadian Empire’s short-lived reign came to an end and was succeeded by the reign of the mighty Empire of America. By ruling over the new beating heart of the Windsor realms in the New World, Robert Borden sat atop all lower powers of the Entente, at least for the time, and would be tasked with leading the return to Europe. In the name of the seemingly eternal Great War, the Atlantic burned as the ships of both the Imperial American Navy and the Workers’ Federated Navy waged war upon an aquatic battlefield. Both sides were prepared for to clash in a war of attrition upon the waves for who knew how many years and neither the Entente nor the Third International would rest until their enemy was vanquished. But as the Third International fought at both land and sea, the Entente would be forced to turn its attention to the corners of its imperium that had been conquered decades before the Great War began.

After all, history has proven that regimes built upon the suffering of their subjects rarely last for long when the elite is incapacitated.

The Headless Snake

"All civilization", said Lord Curzon, quoting Renan, "all civilization has been the work of aristocracies". ... It would be much more true to say "The upkeep of aristocracies has been the hard work of all civilizations".

-Winston Churchill, circa 1909

Indian soldiers and a Gurkha during the Gallipoli Campaign, circa April 1915.

Just like all the great powers of its time, the United Kingdom’s dominance on the world stage had been built upon the backs of those forced into bondage by imperialism. At its peak, the British Empire controlled territory on every single continent on Earth except Antarctica and one fourth of the global population would be subject to the decree of Britannia. It could be said that the sun never set on the British Empire, for the extent of the United Kingdom’s colonial empire was so vast that it wrapped around the entire planet and at no point would the sun not shine on land that waved the Union Jack.

Of course, the wretched system of colonialism that formed the base of the United Kingdom’s superpower status was inherently brutal. The vast majority of subjects of the British Empire held no power in the government that ruled over them, and would instead be victims of the exploitative, and often brutal tactics of the British imperialists to profit at the expense of a quarter of the global population. And out of all of the colonies of the British Empire, it could be argued that no colony had it worse off than the British Raj, a large collection of provinces, presidencies, and princely states that spanned the entirety of the Indian Subcontinent. It was policies deliberately implemented by colonial authorities that killed twenty-nine million Indians in the late 19th Century and it was policies deliberately implemented by colonial authorities that reinforced the oppressive caste system as a way to control the lower classes of the British Raj.

But the stronger they are the harder they fall. Indian soldiers may have fought on behalf of their colonial oppressors during Phase One of the Great War, but as soon as the British Civil War began it was only a matter of time until the Indian masses would rise up in revolution. As the Workers’ Commonwealth proved its strength on the battlefields of southern England, more and more Loyalist soldiers were pulled back from Europe and colonies alike to fight against Inkpin’s revolutionaries. Even as the British Civil War raged on, there were relatively more soldiers remaining in the British Raj than in other British colonies, if only due to the great size and importance of India.

Nonetheless, as the Workers’ Model Army and the British Army clashed in England, India became a powder-keg waiting to explode. Many Indian nationalist movements disavowed violence, which arguably prolonged any revolution in India, but these nationalist organizations would nonetheless expand as the British grip over the Subcontinent weakened more and more. Nonetheless, as demands for revolution grew, a new militant organization would emerge from the pacifist Indian National Congress (INC) of Mahatma Gandhi. Forged in retaliation to Gandhi’s call for an end to all civil resistance by the INC following the Chauri Chaura tragedy of the February of 1922, this new organization would be called the Swaraj Party and would be formed in the January of 1923 under the leadership of Chittaranjan Das.

The Swaraj Party would grow throughout 1923 at a surprisingly rapid rate, often at the expense of the Indian National Congress, and this growth was fueled by Swarajist victories in elections within colonial puppet bodies. Swaraj Party would go as far as to even win control over the Central Legislative Assembly, a legislative body that was ultimately de facto powerless but nonetheless spanned all of the British Raj. By the beginning of 1924, the Swaraj Party was starting to overcome the INC in influence and had easily surpassed the Ghadar Party. Eager to capitalize off of the growing thirst for revolution in India, which was fueled by a mentality that the time for liberation was now when the British Empire was at its weakest point, the Swarajists would remobilize the faltering Non-Cooperation Movement and often encourage more aggressive tactics. Large protests filling up entire cities were encouraged across India by the Swarajists and many Swarajist officials, especially the leaders of local factions, would often promote stockpiling ammunition in case a violent revolution would arrive.

And arrive, a violent revolution did.

Due to the influence of the socialist revolutions of Europe on the Indian nationalist movement, which often saw the Third International as a comrade in the fight against imperialism, socialism found itself an audience within the Swaraj Party. Prominent Swarajists such as Subhas Chandra Bose would adopt varying forms of socialism and the Third International’s policy of supporting anti-colonialist movements, a policy that had been in place since the early 1920s, would mean that collaboration with socialists was a beneficial policy for the Swaraj Party. The Swarajists would even go as far as to form a coalition with the socialist-leaning Ghadar Party and the relatively weak and disorganized Communist Party of India in the February of 1924, thus forming a united Indian socialist movement called the Indian Liberation Union (ILU). As the British Civil War raged on, the British imperialists began to crack down any left-wing movements at an unprecedented rate, with colonial authorities hoping to prevent the Third International from opening up yet another frontline of the Great War. Not long after the beginning of the Second French Revolution, the British had banned all communist activity in the British Raj, which had never encompassed left-leaning organizations such as the Swarajists, however, the formation of the ILU suddenly gave the British the casus belli they needed to suppress the rise of the Swaraj Party.

Not long after the formation of the Indian Liberation Union, all participating organizations would face severe, and oftentimes violent, backlash from British authorities. Chittaranjan Das was arrested on March 2nd, 1924 and he would soon be followed by his fellow Swarajists. The British knew that completely banning the Swaraj Party from elected positions would likely result with a widespread uprising, and so Viceroy Rufus Isaacs, 1st Marquess of Reading would pursue a policy of crushing local Swarajist authority one by one. Viceroy Reading was often more passive and progressive than his predecessors when it came to the British Raj, or at least he tried to be, and it was primarily Prime Minister Lytton who had encouraged a violent crackdown on leftism in India, which explained Reading’s slower approach to combating the Swaraj Party, but when Reading had to use force he would not hesitate.

At first, Reading’s suppression of the Swaraj Party and its allies was actually somewhat successful. Acts of civil disobedience by Indian nationalists increased as Swarajist power was toppled and the Ghadar Party was more sympathetic to the handful of violent riots than its larger ally, but Reading was nonetheless keen on containing purges and insured that such actions would not escalate into violent conflicts by relying more on arrests of elected officials instead of utilizing quick yet messy military force. The acting leader of the Swaraj Party, Motilal Nehru, would ensure that the Swarajists keep up civil disobedience and other forms of protesting as much as possible, but Nehru would not resort to advocating violent revolution, in part due to personal objections and in part due to fears of a revolution being crushed by British military forces.

But when Motilal Nehru was arrested on October 22nd, 1924 and forcefully dragged out of the United Provinces Legislative Council by colonial authorities in an act that captivated Indian public attention (regardless of attempted censorship by the British), the Swaraj Party was infuriated as Nehru, a champion of civil disobedience, was thrown into prison. It was this anger with the apparent failure of peaceful protesting that catapulted the militant Subhas Chandra Bose, the mayor of Calcutta and an admirer of the tactics of European dictators, to the top of the Swaraj Party. Bose would first pursue a policy of centralization within the Indian Liberation Union and ensured that both the Communist Party of India and the Ghadar Party would be organized into effective proxies for Indian independence.

Seeing the threat that Bose’s rise to power posed, Reading would soon order his immediate arrest, hoping to stop Bose before it was too late. But little did Reading know, it already was too late, for when the Indian Imperial Police stormed the residence of Calcutta’s mayor on November 14th, 1924 and attempted to capture Subhas Candra Bose, paramilitary guards protected the revolutionary as he made his escape to the neighboring Howrah, where local Swarajists were organized before Bose. It would be here where Bose would call upon the Swaraj Party to take up arms and begin a war for Indian independence. As word spread of Bose’s speech, revolutionaries would take up arms, and by the end of the day the area surrounding Calcutta had become a warzone.

As Swarajist control over Calcutta was solidified, Subhas Candra Bose would call upon the leadership of the Indian Liberation Union to meet in the heart of the city to officially forge an independent India. It would be in Calcutta that the constitution for the Indian Union was written, thus establishing a centralized government in which the majority of legislative affairs were to be controlled by the national government rather than provincial regimes. Due to the influence of socialists at the Indian constitutional convention, the Indian Union would be a socialist republic in which key industries, such as agriculture and energy production, would be nationalized and all other forms of the means of production would be owned by communities, a system heavily copied from that of the French Commune. Interestingly enough, however, the Indian Union did not adhere to a parliamentary system like many of the socialist governments of the time and was instead a presidential republic in which the president of the Indian Union would be elected every five years.

Upon the ratification of the constitution of the Indian Union on November 26th, 1924 the only territory controlled by rebel government was a handful of pockets of uprising in eastern India that orbited around the de facto capital of Calcutta, which even then was threatened by a growing British military force sent in to suppress the Indian War of Independence (or as Indian revolutionaries and their comrades in the Third International referred to it, the War of Resistance). To the outside world, these bands of rebels were not a sovereign state at all, and the only nations that recognized the independence of the Indian Union early on were the members of the Third International, many of which also happened to suffer from a lack of recognition of legitimacy on the world stage.

Nonetheless, after the rump congress of appointed members was formed, it would elected Subhas Chandra Bose to the presidency of the Indian Union, who was keen on treating his new regime like a legitimate nation and paid at least some respect to its constitution. The constitution of the Indian Union was popular amongst the ILU and would make the Union resemble a legitimate nation, both to the people of the British Raj and to the potential foreign allies. Bose would, however, initiate authoritarian measures to ensure that he could effectively wage a war of independence against the British without the All-Indian Congress getting in his way. Under the mandate of Subhas Chandra Bose and the pressure of the Swaraj Party, the freedom of the press would be censored within the territory of the Indian Union, political parties were required to join the increasingly hierarchical ILU in order to be permitted to participate within the government of the Indian Union, and the Indian presidency was given more authority over the armed forces fighting on behalf at the expense of the authority of the All-Indian Congress.

President Subhas Chandra Bose of the Indian Union.

Regardless of his autocratic tendencies, Subhas Chandra Bose would become a decently popular leader amongst his fellow Indian revolutionaries and would effectively lead the war effort against British imperialism despite arguably fighting an uphill battle. Advancements were slow, but the Indian Union would gradually consolidate its power in Bengal (militaristic progress would especially pick up once the All-Indian Liberation Army (AILA) was formed on December 11th, 1925) and a guerrilla war by pockets of Indian nationalists across the rest of the British Raj would weaken Great Britain’s grip over what was becoming yet another warzone. As the January of 1925 came to an end, the last British holdouts in Assam were vanquished and the British Army would retreat east into colonial Burma. All the while, the Lytton ministry was focusing its attention on the British Civil War as more and more military forces were sent to the battlefields of northern England, thus depleting the British Raj of manpower as the Indian War of Independence raged on.

All the while, the Russian Soviet Republic watched the Indian War of Independence carry out from a distance as Red Army forces left over from the Eastern Front of the Great War were amassed on the Soviet-Afghan border, for Leon Trotsky was waiting for the Indian Union to prove its worth as an ally of the Third International before he made the Himalayas burn in a crimson hue. Ever since the expedition of Soviet Fyodor Scherbatskoy to India in 1919, the Red Army had been contributing to a top secret war plan labeled Operation Kalmyk, in which the Soviet Republic was to invade India by first conquering the Himalayan buffer states that laid between Soviet Turkestan and the British Raj and fund revolutionaries in the region to both bring the Himalayas onto the side of Marxist-Leninism whilst also funneling resources to comrades in India.

Of course, Premier Vladimir Lenin never dared to break Soviet neutrality during Phase One and use what was originally intended to be a defensive strategy against a potential British invasion from Afghanistan, which was subdued by the British around the same time when a coup by Prince Amanullah of Afghanistan was thwarted. In the six years since the end of the Russian Civil War, the Russian Soviet Republic had of course joined the Great War and was an adversary of the British, however, Afghanistan never declared war on the Third International due to the Treaty of Kabul (signed on July 6th, 1919), which ensured that, in return for the continued loyalty of the Afghanistan monarchy to the British Empire, the Emirate of Afghanistan would be protected by the British from a Soviet invasion and would not have to go to war alongside its allies in the Entente against the entirety of the Third International.

But as the Indian War of Independence raged on in Afghanistan’s backyard, Victor Bulwer-Lytton urged his puppet regime in Kabul to declare war on the Indian Union on behalf of the British Empire. Time and time again, the Afghanistan monarchy would refuse to turn its attention away from its increasingly militarized border with the increasingly militaristic Russian Soviet Republic, but on February 18th, 1925 the situation in India would change when British forces were decisively defeated at the Battle of Kharagpur. After four days of heavy sieging, the AILA would quickly overrun Kharagpur and inflicted massive casualties in the process, which not only sent the British into a westward retreat but also punched a gaping hole into British defenses against the Indian Union, which was able to go on a quick offensive. Prime Minister Lytton knew that he could not afford to send any more armed forces off to fight in India without costing the war effort in Great Britain, and so he would instead force Afghanistan to declare war on the Indian Union by threatening to repeal the Treaty of Kabul if the Emirate did not declare war on Bose’s growing insurgency by February 25th, 1925. Knowing that the death of the Treaty of Kabul could very well be the death of Afghanistan, the Emir would accept Lytton’s ultimatum and declared war on the Indian Union on February 22nd, 1925.

But little did the Emir know that, ironically enough, cooperation with the British would spell doom for Afghanistan. As the majority of mobilized forces within the Afghanistan armed forces were sent into the British Raj, holes began to emerge in defenses against the Soviet Republic, which the strategic Leon Trotsky saw as the perfect moment to pierce into India and liberate his comrades for the personal gain of the Third International. After a quick last-minute buildup in Turkestan, the Red Army was ready to open up yet another frontline against the Entente in the ever-growing Great War and only had to wait for orders to come down from Moscow in order to initiate Operation Kalmyk. And these orders would finally come down from Premier Trotsky on March 21st, 1925. Within minutes, LT tanks had entered Afghanistan and had thrown the Emirate of Afghanistan into the middle of the bloodiest war in human history.

The Himalayan Front of the Great War presented a new challenge for the Red Army, which was more accustomed to the plains of eastern Europe than it was to the mountains of southern Asia, but it was a challenge that General Mikhail Tukhachevsky would accept. A veteran of both the Russian Civil War and the invasion of Ukraine, Tukhachevsky was as experienced as he was aggressive (Tukhachevsky’s brutality in Ukraine had earned him much notoriety within the Ukrainian State, even if his actions were often lumped together with those of General Joseph Stalin), and it would be this experience in brutality that put Mikhail Tukhachevsky in command of the invasion of one of the most populous regions in the world.

General Mikhail Tukhachevsky of the Russian Soviet Republic upon arriving in Termez, circa March 1925.

As Tukhachevsky began the invasion of northern Afghanistan, the general would employ his staunchly offensive tactics of quick and heavily armed pushes that would exhaust the enemy. Years later, these tactics would become the basis for the deep operation tactics of Phase Three and Phase Four, but for the time being Tukhachevsky’s strategy was merely a relatively simple offensive that took advantage of the Soviet Republic’s industry and population, and it was a successful offensive at that. Even as British and Afghan forces were alleviated from the war in the British Raj to fight against the forces of communism, Operation Kalmyk dug deep into Afghanistan in the spring of 1925 alone. The mountainous terrain of northern Afghanistan proved to be annoying for the Red Army to pass through and made for an excellent hideout for guerrilla forces, however, tanks were capable of leading soldiers through the rough terrain while Soviet airplanes bombed Afghan positions from above without facing much retaliation due to lackluster Afghan air defense.

On June 12th, 1925 Kabul, the capital of the Emirate of Afghanistan, would fall to the Red Army, which not only meant that the fall of the Emirate would soon arrive but also left the Afghan-Indian border more or less exposed to a potential Soviet invasion. As the summer of 1925 began, Tukhachevsky would focus on ensuring that what remained of the Emirate would be crushed by the might of the working class, and southern Afghanistan would become yet another corner of hell, a product of the Great War, although the South Asian Front became a much more bloody fight for the Red Army as Loyalist veterans of the British Civil War were deployed in Asia with a score to settle with the Third International. As the war against the Workers’ Commonwealth turned into a primarily naval conflict, thousands of soldiers of the British Army were no longer required in the reconquest of Europe, at least for the time being, and would instead become much-needed reinforcements in the frontlines of the southern Asia.

Nonetheless, even as the South Asian Front slowed down, the Red Army would ultimately emerge victorious in the battlefields of Afghanistan. The size and technological strength of General Tukhachevsky’s military invasion would ultimately overwhelm joint defenses by both the Emirate of Afghanistan and the British Empire, and as the fall of 1925 began the last holdout of Entente forces in Afghanistan would fall after a Red Army victory at the Battle of Rudbar on September 14th, 1925. As the defeated Anglo-Afghan defenses moved south from Rudbar, Emir Habibullah Khan recognized that what was now the Empire of America could not save Afghanistan from the Soviet Republic, and at least capitulation could achieve exile for Habibullah and his family. Therefore, on September 16th, 1925 the Emirate of Afghanistan would capitulate to the Russian Soviet Republic, and like Ukraine, a Marxist-Leninist puppet regime called the Democratic Federation of Afghanistan was established with Premier Abdul Majid Zabuli instated as the leader of both Afghanistan and the ruling United Democratic Workers’ Party (UDWP).

With Afghanistan yet another pawn of the Third International within the Great War, the Soviet invasion of the British Raj could truly begin. In the September of 1925, Red Army soldiers and LT tanks would race for the Indus River while the Indian Union pushed towards New Delhi in the name of the liberation of all of India from the grip of the Empire of America. By the time October had begun, rebellions were sprouting up all across India. On September 28th, 1925 Advocate-General Seshadri Srinivasa Iyengar of the Madras Presidency called on the Madras Province Swarajya Party (MPSP), which had held a majority of seats within the Madras legislative council since a snap election in June, to declare the Madras Presidency an independent socialist republic. After the MPSP, in collaboration with a handful of members of the declining Justice Party, overthrew British control in Madras, the People’s Republic of Madras was declared following the ratification of a constitution on October 8th, 1925, and a decentralized federation of communes was born along the coastline of India.

And so, as rebellion spilled throughout India in the east and the Red Army conquered what had once been the greatest colony of the British Empire from the west, it appeared as though the sun would only continue to set on the legacy of the British Empire. The German Heilsreich had long since beaten the Empire of America when it came to naval power, the fight for the reconquest of Great Britain had bogged down into a naval war of attrition, imperialists and nationalists alike were beginning to eye Imperial colonies in Africa, and soon the British Raj would be no more, replaced by a league of revolutionary states. But even as the Entente was all but defeated on the European continent and was just barely holding onto its remaining colonies, its fight in the Great War was far from over. Robert Borden had mobilized his new empire into a force for King and Country that would fight until the bitter end and the French Fourth Republic was holding on in Algiers. But nonetheless, new support would be necessary if the Entente had any chance of surviving to 1930.

And this new support would soon arrive in the form of a new ally.

The reign of Brazil over the New Western Civilization was on the horizon.

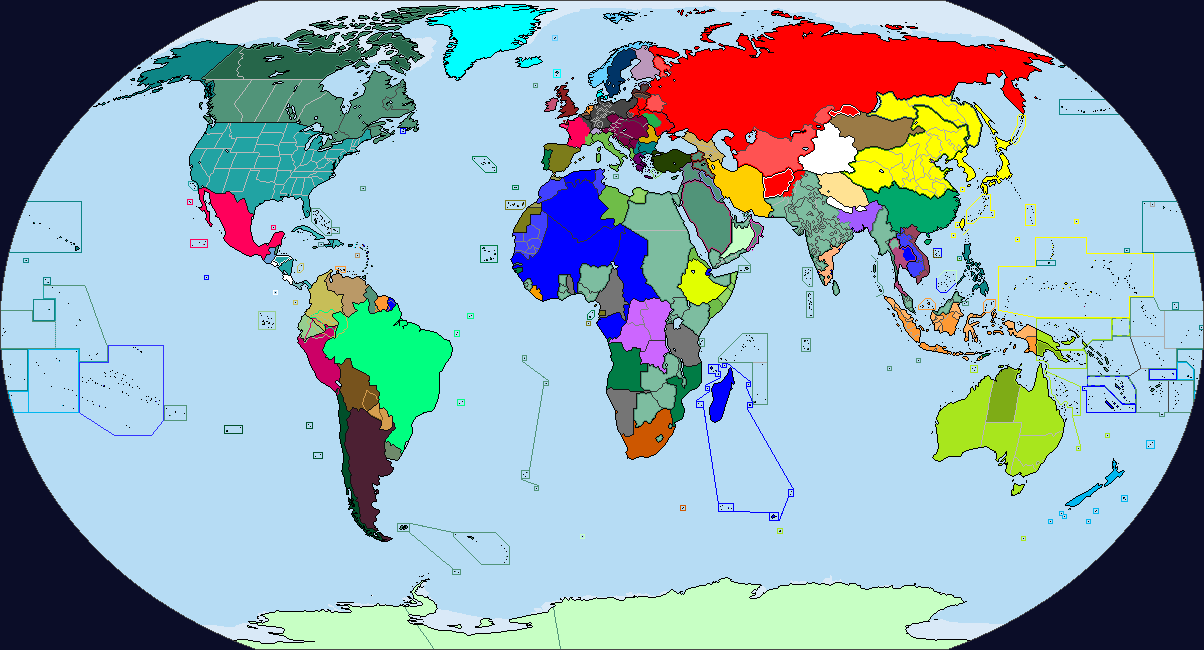

Map of the World circa November 1925.

“Now they want me - now they want us - to leave Europe. Maybe forever.”

-King George V in a private conversation with Mary of Teck, circa December 1924.

King George V of the United Kingdom.

Halifax, Canada, circa January 5th, 1925:

As a large ship sailed towards the city, a crowd of civilians, reporters, and even political officials gathered alike awaiting its arrival. As this ship got closer and closer and the Union Jack could be made out in the distance, camera crews got into their positions while reporters scrambled to get as close as possible to where the important passengers of this ship would step foot into Canada. A few more minutes passed, and soon enough the ship had docked into the crowded Halifax harbor. Once a gangplank was set up, out stepped none other than King George V of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and the British Dominions, a living symbol of the nation that had ruled the world for over a century. Dressed in a coat suited for the cruel Canadian winter, His Majesty was accompanied by the Queen Consort, Mary of Teck, and was followed by his children, including the eccentric Prince Edward, who was notably the only aristocrat entering Canada who visibly smiled and gave the crowd held back by a crude fence the attention they craved.

Bearing a sleek top hat, King George V made use of the rim of his head attire by avoiding looking at the crowd his eldest child happily entertained. The people of Halifax cheered for their king, although the clapping was relatively unenthusiastic and was more sympathetic to the attitude all who bowed to the British Empire had been overcome with since the beginning of Phase Two of the Great War. Sure, “God save the King!” could always be heard from the crowd, but its tone was generally less jubilant than usual, and it was accompanied by “the Empire stands with Great Britain!” and “the House of Windsor will never fall!” Anyone at the harbor could feel this somber atmosphere, and a handful of years later King Edward VIII would describe the welcoming crowd in Halifax as “a funeral for a dead nation.”

Before entering an elegant automobile decorated with the Royal Standard of the United Kingdom, King George V would approach Canadian Prime Minister Robert Borden, who went through a traditional and well-rehearsed greeting to the sovereign of what was still, at the end of the day, the largest empire in the world. As the two men exchanged greetings, George V revealed a faint smile to the Prime Minister, all the while understanding that it would be the Canadian government rather than its British counterpart that His Majesty would primarily be working with from now on.