Chapter Three: The Sleeping Giants

Chapter III: The Sleeping Giants

“At long last, Japan has become capable of promoting a greater future for all of Asia. May the dawn of peace with Germany be the prelude to a greater peace on the Asian continent.”

-Japanese Prime Minister Inukai Tsuyoshi addressing a crowd in Tokyo following the Treaty of Fukuoka

Japanese soldiers in Vladivostok moving south to Korea, circa 1919.

When one focuses on the history of the early 20th Century, nearly all attention is ceded to the Great War. After all, the Great War was by far the bloodiest conflict ever fought in human history. With that being said, however, the history of the powers that maintained neutrality throughout the duration of the Great War is also incredibly important, especially when seeking out the origins of the post-war geopolitical climate. Therefore, it is necessary to delve into the history of the “sleeping giants” of the Great War; the United States, Italy, China, and Japan in order to completely understand what the politics of the world were like during the Great War.

After the Empire of Japan negotiated its removal from the wrath of the Great War with Germany, the Japanese government immediately shifted its attention to its western neighbor, China. As of recently, China had been the victim of plenty of violence despite not being involved in the Great War. In the December of 1915, President Yuan Shikai of the Republic of China was declared the emperor of the Empire of China in an attempt to bring stability to the rapidly deteriorating Chinese government. Yuan’s coronation, however, was met with retaliation from those who still supported democracy and put up resistance to the Hongxian Emperor (the new title for Yuan Shikai) as southern Chinese provinces seceded and forged the National Protection Army to fight against the Empire of China and restore the destroyed republic.

Yuan Shikai, the Hongxian Emperor of the Empire of China.

While the Empire of China initially appeared to have an advantage over the secessionist republican provinces in the south, the unpopularity of the Hongxian Emperor would severely harm the war effort. The independent provinces loyal to the National Protection Army somehow overcame their shortcomings due to the vast array of discontent within the high command of the Beiyang Army. As pressure to abandon the Empire of China grew, Yuan Shikai abdicated from his position as the monarch of China in the March of 1916, and on July 14th, 1916 the National Protection War ended with a victory for the southern republicans following Yuan Shikai’s death in the prior June. In the aftermath of the collapse of the Empire of China, numerous members of the Hongxian Emperor’s Beiyang Army became warlords, and China fell apart.

The National Protection War was merely background noise as the Great War raged on, however, the Japanese were especially concerned with the crisis to their west. The fates of Japan and China were intertwined, and cooperation between the two became increasingly precious once Japanese imperialism entered the Asian mainland. By the time the Empire of Japan left the increasingly destructive and chaotic Great War, National Protection War had concluded and China’s stability was rapidly deteriorating. While the Republic of China was restored, warlordism was increasingly rampant and the internal politics of the Chinese democracy were becoming more and more polarized. Under the leadership of Sun Yat-Sen, the nationalist Kuomintang rose to become the opponent of President Li Yuanhong and Premier Duan Qirui. It was apparent to all in China that the government of the re-established republic was on the brink of internal collapse, and all it would take was one spark.

Unfortunately for the Republic of China, that spark did come. General Zhang Xun, a staunch monarchist who was previously loyal to the Hongxian Emperor, would invade Beijing in the June of 1917 and forced President Li to dissolve the Chinese parliament, and restored the young Puyi of the fallen Qing Dynasty as the emperor of China on July 1st, 1917. Li Yuanhong and his supporters would evacuate north to Manchuria, where Duan Qirui was tasked with protecting the rapidly deteriorating Republic of China after defeating an attempt to restore the Chinese Qing monarchy in Manchuria. Due to bad experiences with the institution in the past, Duan Qirui would dissolve the Chinese parliament, which caused Sun Yat-Sen and his allies in southern China to establish a rival republican government in the hands of the Kuomintang.

And thus, the Chinese Civil War had begun.

Less than a year after Yuan Shikai’s Empire of China was defeated, China was engulfed in an internal war yet again as the Republic of China shattered apart into factions of warlords. The Kuomintang-led Guangzhou Government of the southern provinces and the so-called Tianjin Government (named after the city of Tianjin, where Li Yuanhong’s government consolidated power following the chaos in Beijing) found themselves opposed in a war for control of one of the largest and most ancient nations to ever exist. The two governments immediately set out to consolidate their power, with Duan Qirui installing relatives into positions of power within the Tianjin Government, while the Guangzhou Government consolidated power by becoming a one-party military junta led by Sun Yat-Sen.

Premier Duan’s tendency to put his relatives in powerful positions would only harm the stability of the government he was supposed to keep together. In the shadows of the Tianjin Government, enemies of Duan Qirui rose up and would push for taking power away from the ambitious man. Li Yuanhong would retire from the presidency early in the August of 1917 and was succeeded by his vice president, Feng Guozhang, who intervened in the crisis involving his premier by pressuring Duan Qirui to resign, although there was much discontent produced by Duan’s underlings in retaliation that could have very well led to the return of Duan Qirui had not he personally insulted President Feng following his forced resignation.

When the Chinese Civil War broke out in the summer of 1917, the world ignored the crisis in the east. After all, the conflict was nothing compared to the international catastrophe that was the Great War and therefore was of little concern to European, or for that matter, western affairs. The Japanese, however, continued to keep an eye on China as Tianjin and Guangzhou clashed, and many Japanese political officials were fearful that the civil war could potentially risk their dreams of Pan-Asian collaboration. In fact, the Chinese Civil War was one of the many factors that contributed to the Japanese and Germans sitting down for peace talks in Fukuoka, due to many in Japan desiring to intervene in the Chinese Civil War rather than waste lives and resources on the seemingly pointless and increasingly deadly Great War.

Upon leaving the Great War, Prime Minister Inukai Tsuyoshi shifted attention to China, and as the Russian Democratic Federative Republic stabilized Japanese soldiers were called south in preparation for any potential intervention in China. If Japan were to enter the Chinese Civil War, it was obvious which faction they would support. The hostile and nationalist Guangzhou Government would never become an ally of the Empire of Japan, and was anticipated to become a rival of the Japanese should Sun Yat-Sen and his Kuomintang emerge victorious over all of China. Furthermore, there were many pro-Japanese elements within the Tianjin Government, which would guarantee that diplomacy between the two regimes was not only possible, but would most likely go over well for the increasingly desperate Feng Administration.

In the November of 1919, the new premier of the Tianjin Government, Wang Daxie, briefly visited Japan and would speak in front of the Imperial Diet, imploring its members to support the Tianjin in its war against the Kuomintang. Wang’s diplomatic mission proved to be a success, and on December 2nd, 1919 the Japanese government, which had already been loaning resources to the Tianjin Government for awhile, agreed to deploy soldiers in China in order to fight the Guangzhou Government to the south. Within the next few days, history would accelerate as the RDFR would join its ally, Japan, in the Chinese Civil War and, soon enough, experienced Russian officers who had fought on behalf of the Green Army were fighting in China alongside the Japanese and Chinese. In order to consolidate an alliance, the three nations would meet in Tonghua to officially establish an official alliance. The Tonghua Pact, a mutual defense and free trade coalition, was formed on December 22nd, 1919, and ensured the cooperation of all three regimes (as well as the Japanese military occupation of the RDFR and Tianjin Government for the foreseeable future), while also becoming the first step towards the upcoming East Asian Co-Prosperity Sphere.

Step by step, Asia was moving closer and closer to a unified government.

Bloodshed in the Yangtze

“I remember the Yangtze River well. When I was a young man, fighting on behalf of Chinese democracy in the Tianjin Army, it was at the banks of the Yangtze where I saw the worst horrors of war firsthand and gazed into the eyes of death itself.”

-Premier Mao Zedong addressing the East Asian Diet, circa 1941.

Emblem of the Kuomintang, the supreme political party in the Guangzhou Government and its successor, the National Republic of China.

Once the Tianjin Government assembled a coalition of regional powers, the preparation for the long push south commenced. Of course, in order for the Tianjin Government to win the Chinese Civil War, internal stability would need to be accomplished first. Feng Guozhong would exit the presidency of China in the October of 1918, and was succeeded by Cao Kun following an election, while the Communication while the bureaucratic and labor unionist Communications Clique secured a majority of seats in the Tianjin Government’s parliament. It was uncovered that Duan Qirui had attempted to rig the 1918 Chinese elections in favor of his Anfu Club, however, such attempts were uncovered and Duan’s already collapsing political career shattered. With public support of Duan nearly annihilated, the disgruntled military officer would consolidate his remaining power in the provinces of Anhui, Shaanxi, Suiyuan, and Chahar and declare war on the Tianjin Government on January 8th, 1919.

Duan Qirui, the leader of the Anhui Clique.

Duan Qirui’s new Anhui Clique would not choose to realign with Sun Yat-Sen’s Guangzhou Government, therefore meaning that it would have to simultaneously defend against both Tianjin and Guangzhou. Japanese intervention in the Chinese Civil War was still nearly a year away, however, the severely weakened Anhui Clique could not take on both sides at once and is two rival factions were far more populated and better equipped. The province of Anhui was partitioned in half by the dawn of the April of 1919, while Tianjin Government turned its attention to what remained of Duan’s regime. The Anhui Clique was definitely a threat to President Kun (especially once a handful of pro-Duan military commanders defected), however, the Clique was no match to the Tianjin Government and would rapidly lose territory within months. Thus, on June 29th, 1919 the Anhui Clique would completely collapse and was reintegrated into the Tianjin Government, while Duan Qirui and a few of his most loyal officers would evacuate west, living out the rest of their lives in retirement in Xinjiang.

Therefore, when the Empire of Japan arrived in northern China, the Tianjin Government was a stable and moderately powerful member of the Tonghua Pact and was ready to progress south against the Guangzhou Government. Sun Yat-Sen had taken advantage of the distraction that was the Anhui Clique, and progressed both west and north. By the time the Japanese had declared war on the Guangzhou Government, the Kuomintang’s National Revolutionary Army (NRA) had nearly pushed the Tianjin Government completely out of the Anhui province, and if it wasn’t for General Sun Chuanfang, Jiangsu would have fallen into the hands of Sun Yat-Sen months ago and the Kuomintang would be invading Sandong.

Even though it had the strongest nation in Asia on its side, the Tianjin Government would be in a fight for its very existence throughout 1920.

Under the command of Hideki Tojo, the Imperial Japanese Army pushed for the Yangtze, hoping to contain the Guangzhou Government in the southern provinces. Thousands of veterans of the Great War, both Japanese and Russian alike, would progress deep into the Guangzhou Government, and by the start of the March of 1920, China was divided along the Yangtze River, where the two factions of the Chinese Civil War exchanged gunfire over Asia’s largest river. Not even Lu Rongting, the individual who had presided over the NRA’s invasion of Jiangsu, could cross over into the north and the same situation applied to his counterparts, who returned gunfire to him every single passing day.

As the Chinese Civil War shifted into a war of attrition, the two factions began to endorse a peaceful end to the bloody conflict. The leaders of the Tianjin Government had actually supported negotiations for awhile, and Sun Yat-Sen’s aggression had been the only thing preventing a ceasefire being applied. However, as the situation for a breakthrough by the NRA became increasingly more implausible (not only that, but the Tonghua Pact was investing more and more resources and if things stayed the same, Cao Kun would eventually be able to call himself the unifier of China) Sun Yat-Sen entertained the idea of a diplomatic end to hostilities. Increasing pressure from Lu Rongting and likeminded officers commanding along the southern banks of the Yangtze would be the straw that broke the camel’s back and on October 11th, 1920 representatives from both Tianjin and Guangzhou, as well as their respective allies, would arrive in Hangzhou to come to a peaceful agreement.

After half a decade of bloodshed, China was at peace yet again.

After days of negotiations, the two factions finally managed to come to an agreement. China would be partitioned roughly down the Yangtze River between two governments. In the south, the Kuomintang would be free to assert its authority and centralize whatever provinces it occupied, while the Tianjin Government would control the northern provinces, with the exception of Xinjiang, which had asserted its independence under the monarchist Yeng Zengxin, the very last remnant of the Empire of China. The two Chinas did, however, have to agree to give up the official name “Republic of China,” in order to avert disputes over which state was the true successor to the unified Chinese democracy.

In the south, President Sun Yat-Sen declared the National Republic of China (NRC), a one-party military junta clenched within the iron fist of the Kuomintang. The NRC was immediately quickly centralized, and Sun Yat-Sen was declared the South Chinese president for life. Once all political parties, excluding the Kuomintang, were banned in South China, political dissidents and rivals of Sun who refused to conform to his dictatorship, were forced into exile or would face imprisonment or even execution. The nationalist junta of President Sun would quickly begin its industrialization in the upcoming years, and upon the death of Sun Yat-Sen in 1925, his cronies would begin to clash over who would become the next president of the National Republic of China.

Flag of the National Republic of China.

In the north, the Tianjin Government would rename to the Provisional Government of China in accordance to the Treaty of Hangzhou, however, this term was short-lived. By the end of the October of 1920, a new constitution for the Provisional Government was approved and on October 29th, 1920 the Chinese Federation was declared, with its capital in Beijing. Just like the name implies, North China was a federal democracy, a move conducted in part to satisfy the numerous autonomous warlords and governors who had presided over their respective provinces throughout the duration of the Chinese Civil War. Cao Kun would lead the Chinese Federation as its first president until 1927, when he lost an election to the dominant Youchuanbu Party, which had governed the legislative assembly of North China since the election of 1918 back in the Tianjin Government. The Chinese Federation would adopt the flag of the Republic of China as its banner, which had been adorned by the Tianjin Government beforehand.

Flag of the Chinese Federation.

After the Chinese Civil War concluded and the ink dried on the Treaty of Hangzhou, the Chinese Federation and its allies would preserve the Tonghua Pact, which became the dominant peacekeeping force on the Asian government, especially whilst the great powers of Europe were distracted by their nightmarish inferno of a war. In the November of 1920, the Bogd Khanate of Mongolia became the fourth member state of the Tonghua Pact due to fears of a potential Soviet incursion, especially after Tannu Tuva fell to communism, becoming the Tuvan People’s Republic, a Soviet puppet state, near the conclusion of the Russian Civil War. Throughout the 1920s, the Empire of Japan would reduce its military presence in both North China and RDFR, therefore securing the autonomy of the two nations, however, Japanese military bases would always exist within the two states, especially along the increasingly militarized Yangtze River.

The history of Asia and Europe in the 20th Century were, in many ways, parallel to each other. One continent would enter the new century as the masters of the world, while the other entered as the servants of the other. One was plunged into an era of unimaginable horror and bloodshed, while the other moved towards a greater peace that would end previous chaos. And of course, one continent’s global domination would be absorbed by the other. As one sun set, another would rise.

Decision 1920

“Stronger than a Bull Moose”

-Popular 1920 presidential campaign slogan for Hiram Johnson

United States Capitol building, circa 1910.

The United States of America is notorious for staying completely neutral throughout all of the Great War. Aside from condemnation of controversial wartime activities, such as the sinking of the Lusitania or the Wehrstaat Declaration, and the selling of supplies primarily to the Entente, the United States would stay completely out of the mess that war the Great War. Of course, this was by no means unprecedented. Despite being considered a great power that rivaled even the greatest empires across the Atlantic Ocean, the United States had a history of not only staying out of foreign affairs, but also keeping other powers out of their own affairs in accordance with the Monroe Doctrine, which had been put in place for nearly a century when Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated one day in the June of 1914.

President Woodrow Wilson, the first Democrat to reside within the White House since the presidency of Grover Cleveland, had actually campaigned (and won) in 1916 with the slogan “he kept us out of war” and intended to continue to preserve American neutrality. Instead, President Wilson focused on domestic concerns throughout the duration of his second term, and his actions would often infuriate northern progressives, Republican and Democrat alike. Despite serving as a the governor of New Jersey prior to being elected president in 1912, Woodrow Wilson was actually born in Virginia and was absolutely a southern Democrat. It was Wilson who would institute segregation upon federal offices, and discriminatory hiring practices were only increased by the Wilson administration.

President Woodrow Wilson of the United States of America.

Economically, Woodrow Wilson was rather populist, however, it was his socially conservative ideology that would get him more attention. The racism of the Wilson administration would continue throughout his entire second term, however, his suppression of labor strikes, many of which were put down violently, became especially prominent as the 1920 presidential election neared. Feminism would also grow throughout his second term, however, Wilson and like-minded Democrats were keen on ensuring that the rights of women would be not determined by the federal government, but rather by local governments within the forty-eight states of the United States. This, coupled with the outbreak of a vicious disease, named the Kansas Flu, in 1918 would diminish the support of the Wilson administration.

By the time Woodrow Wilson’s second was nearing completion, the president was increasingly unpopular and there was no way the Democratic Party would nominate President Wilson for a second term. Not that Woodrow Wilson would run in 1920 anyway, his physical health was declining every day, especially after President Wilson fell ill with the Kansas Flu himself. Therefore, the Democratic Party would have to find a new candidate for the presidency, and plenty of men took up the challenge to win the support of one of the largest political organizations within the United States. While William Gibbs McAdoo, Wilson’s son-in-law, appeared to become the Democratic candidate, Woodrow Wilson suddenly took a gamble at being nominated for a third term by preventing McAdoo from winning the nomination. All this did, however, was doom McAdoo’s chance to become the next president and the Democratic National Convention selected Governor Carter Glass of Virginia instead, and Alexander Mitchell Palmer was chosen to be his running mate.

Carter Glass.

The Republican Party, the opponents of the Democrats, would retaliate to the socially conservative Glass by pushing for a progressive from former President Theodore Roosevelt’s sect of the party in order to win the support of progressives across the United States and paint the Democrats as a reactionary party that had stubbornly held back social progress for nearly a decade (which was not completely false, if it weren’t for the faction of progressive Democrats within the party’s ranks). Of course, more conservative members of the Republican Party were still present within the 1920 presidential primaries, most notably Governor Frank Orren Lowden of Illinois, however, the conservative policies of the Wilson administration pushed the progressives to the top and, following the death of Theodore Roosevelt in 1919, the former president’s personal choice, Senator Hiram Johnson won the support of the Republican National Convention, and Senator Irvine Lenroot of Wisconsin became his running mate.

The race for the White House had begun.

As the clock ticked down to the day Americans would select their next president, the complete contrast between Johnson and Glass became extremely obvious. While both men were opposed to American entry into the Great War, their similarities ended there. Economically, Hiram Johnson endorsed the anti-trust policies of the late Theodore Roosevelt and supported collective bargaining between labor unions and corporate leaders in accordance to his advocacy for direct democracy. Carter Glass used such policies as an excuse to label Senator Johnson as a socialist, a claim that was popular amongst the conservative sect of the Democratic Party, but seemed a bit more ridiculous amongst Republicans and moderate Democrats.

Socially, the two men were also opposites. Glass’ support of states’ rights would cause him to declare that he would leave the issue of female suffrage to local governments (like his predecessor), while Hiram Johnson eagerly endorsed gender equality as a way to win over plenty of American progressives with ease. Another major issue that the two candidates battled over was segregation. In order to not destroy all support he had in the southern states, Johnson never straight out endorsed pushing towards racial equality, however, he did announce his support of ending Woodrow Wilson’s policies of segregation in federal offices. Glass, on the other hand, was one of the strongest proponents of Jim Crow laws within the United States, perhaps even stronger than Woodrow Wilson himself. This support of segregation would lead Carter Glass to propose the implementation of nationwide poll taxes as a way to keep poor African-Americans from voting, although he painted such a proposal as a way to keep communists from potentially winning any elections, at a debate with Senator Johnson. To this, Carter’s rival would say, “I see, you seek to forcefully suppress the communists? Why don’t you ask Mr Brusilov how that worked out for him?”

Carter Glass’ controversial support of nationwide poll taxes to keep poorer Americans away from ballots was arguably one of the most harmful blows to his bid for the White House. Many moderate and liberal Democrats were deeply disturbed by such a proposal, which would cause a divide within the party. One prominent Democrat who condemned Carter Glass was Franklin Delano Roosevelt, the Assistant Secretary of the Navy in Woodrow Wilson’s cabinet, and prominent progressive Democrat. After Glass’ announcement of supporting nationwide poll taxes was in the headlines of national newspapers, Franklin D Roosevelt announced that he would not vote for Carter Glass, deeming him a man who “would rather see democracy die than lose power.”

Roosevelt’s bold statement would turn him into a new symbol for progressive Democrats and an enemy of the conservative faction of the Democratic Party. In order to guarantee that his administration was still supportive of Carter Glass, Woodrow Wilson would fire Franklin Delano Roosevelt late in the September of 1920, which only further infuriated Roosevelt and his sympathizers. After losing his job, Roosevelt concluded that the Democratic Party was little more than a corrupt cabal of southern conservatives, and would invite several moderate and progressive Democrats to New York City. It was here that these like-minded politicians left the Democratic Party to forge their own new organization, named the Liberal Party, on October 10th, 1920. The founder of the Liberals, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, easily managed to become his new party’s first chairman, which automatically won him national fame.

Chairman Franklin Delano Roosevelt of the Liberal Party.

Due to having numerous policies that resembled the larger Republican Party, as well as choosing to endorse Senator Hiram Johnson rather than run their own presidential candidate in 1920, the Liberal Party quickly earned the nickname “Little Republicans.” That is not to say, however, that the Liberal Party did not have its own unique platform. The Liberals endorsed national female suffrage and Chairman Roosevelt in particular pushed for social welfare programs to help benefit the less fortunate of the United States, and the Liberals were especially opposed to poll taxes, one of the primary reasons why the Liberal Party had left the Democrats to begin with. While the Liberal Party did not openly consider itself an opponent of segregation, arguing that dividing black and white Americans in society was an affair of the states, opposition to poll taxes would turn the Liberals into opponents of restricting the African-American vote. Overall, the Liberal Party could be considered an adherent to the ideology of social liberalism, which more or less accurately describes the views of nearly all members of prominence.

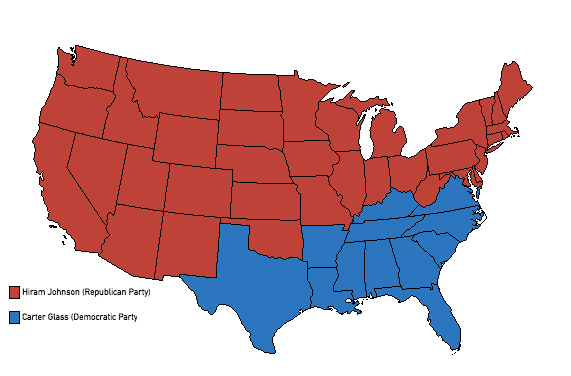

The 1920 presidential election was held across the United States on November 2nd. Voter turnout was substantially large, especially due to fears that a national poll tax under a Glass administration would potentially prohibit plenty of Americans from ever voting again. If one were to look at an electoral college map, it would resemble numerous elections dating back to 1880. The northern states were solid Republican territory, while the southern states belonged to the Democratic Party. The west coast, the region Hiram Johnson originated from, easily went to the Republican Party, although anything within the Mississippi River and the Pacific Coast was a bit more contentious. In the end, however, this region was primarily won over by the ticket of Johnson and Lenroot, and by the midnight of November 2nd, 1920, it was obvious to the United States who would succeed President Woodrow Wilson.

After eight years, a Republican would be back in the White House.

Electoral college map of the 1920 United States presidential election.

While a victory for Hiram Johnson had been typically anticipated, especially when Franklin D Roosevelt formed the Liberal Party, the most devastating losses for the Democratic Party was in Congress. It was here where the Republicans not only secured a majority in both the House of Representatives and Senate, but the Liberal Party won numerous previously Democratic seats, especially in the northeastern states. As the days until Johnson’s inauguration in March began to pass by, the president-elect would start to endorse cabinet positions. Democrats were almost completely excluded from the upcoming cabinet of the Johnson administration, however, Liberals and a diverse array of Republicans would find positions in the executive branch.

Leonard Wood, a military officer from New Hampshire and progressive Republican, was almost immediately chosen to be the next secretary of war while Elihu Root returned to the position of secretary of state, which he had held during Theodore Roosevelt’s presidency. Rumors of the nomination of Franklin Delano Roosevelt as the Johnson administration’s secretary of the navy would circulate, however, in the end Roosevelt chose to remain the chairman of the Liberal Party and the Liberal Admiral Joseph Strauss was chosen for the position instead. The moderate Republican Calvin Coolidge was chosen to be the attorney general under Hiram Johnson, however, the other cabinet positions were filled with mostly progressive Republicans, such as Senator Robert Marion La Follette of Wisconsin.

When Hiram Johnson was inaugurated to become the twenty-eighth president of the United States of America on March 4th, 1921, the United States Capitol building was surrounded by a vast crowd eager to witness the inauguration of Johnson firsthand. For it was obvious to the whole nation that a new era had come upon the United States, one of progressivism, welfare, and social progress. Women were almost guaranteed that they would have the right to vote by the end of the year, and surely enough the Nineteenth Amendment was approved less than a month into the Johnson administration, only to be succeeded by the more radical Equal Rights Act and Twentieth Amendment a year later. The masses of the American workplace celebrated as the advancement of their rights from the days of the Roosevelt administration had been promised to return. President Hiram Johnson would bring upon a new age of American progressivism, one that had not been seen for well over a decade.

The Democratic Party, on the other hand, was doomed to things far worse than anyone could have ever imagined.

President Hiram Johnson of the United States of America.

The Eye of the Hurricane

“Our nation finds itself within the center of a storm. I implore my successor to not succumb to this storm’s brutality, for I fear that this storm could blow down our nation with ease.”

-Italian Vittorio Emanuele Orlando’s farewell address, circa 1920

Flag of the Kingdom of Italy.

When the Great War began, the Kingdom of Italy had just barely managed to stay out of the bloodbath that had overrun the rest of Europe within just a handful of days. Prime Minister Giovanni Giolitti and his successor, Vittorio Emanuele Orlando, were keen on preserving Italian neutrality throughout the Great War, choosing to focus on the improvement of the Italian military in navy in case the Great War came knocking on the Kingdom of Italy’s door. As a consequence of the military buildup, by 1920 the Italian armed forces rivaled that of the belligerents of the Great War, and the Red Army was the only neutral military force in Europe larger than that of Italy.

Throughout all of Phase I, a desire for Italian irredentism, and therefore entry into the Great War, would only grow. Multiple Italian politicians, including members of Orlando’s Liberal Union, would encourage joining one side or the other of the Great War, however, as it became increasingly unclear which side would emerge victorious, the Italian people shifted away from purely endorsing the Entente, especially after the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk was signed. Besides, as the date for the negotiations guaranteed by the Treaty of Vienna. As the Germans became especially concerned with ending the war on the western front as quickly as possible, perhaps Italy’s opportunity to force whatever Rome wanted out of the Central Powers had arrived.

Surely enough, Austro-Hungarian and German diplomats would sit down with their Italian counterparts in Budapest on June 17th, 1920 to decide the fate of South Tyrol, Dalmatia, and Albania. The easiest territory for Austria-Hungary to cede to the Kingdom of Italy was Albania, which was technically not Austro-Hungarian territory to begin with. Instead, Albania was a nation that had fallen under total Austro-Hungarian military occupation after choosing the wrong allies in the Great War, and only a few Austro-Hungarian military commanders grumbled about the cession of Albania to the Kingdom of Italy. In accordance to the Treaty of Budapest, the Kingdom of Albania was transferred into the hands of the Italians as a protectorate with a local prime minister who would be overseen by an Italian governor-general, and King Victor Emmanuel III of Italy was crowned the king of Albania.

Flag of the Kingdom of Albania.

Other territory subject to debate via the Treaty of Vienna was more contested. Dalmatia was Austro-Hungarian land and had been in the hands of Vienna for quite some time, and it was therefore very embarrassing for Emperor Karl I to give up to the Kingdom of Italy. Still, ceding Dalmatia was nothing compared to the debate over South Tyrol and Trentino, the former of which was dominated by Germans while the latter was a valuable port to the Adriatic Sea for the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Neither would be easy to pry from Austria-Hungary, even if the German Empire would in many ways be on the side of the Italians in order to keep the western front as small as possible.

In the end, the Kingdom of Italy would get to control Trentino, but not the German-majority South Tyrol. The cession of Trieste, Austria-Hungary's most valuable port, was even more unlikely than South Tyrol, however, some territory to the west of Trieste was given to Italy as a compromise. The Kingdom of Italy was also promised Tunisia, Corsica, and a vague chunk of territory in southwestern France if the Central Powers managed to capitulate the French. A five-year-long non-aggression pact between all involved parties was also signed in order to ensure that Italian soldiers would not be pushing for Vienna anytime soon.

The Treaty of Budapest was by no means ideal for either party involved, however, the Italians mostly viewed it as a victory and backed down on further aggression towards Austria-Hungary. The public opinion of the Central Powers became much more positive in Italy, and Germany and Austria-Hungary began to be depicted as nations that honored their treaties, as well as Italian allies. The Entente, on the other hand, became a target for future Italian irredentism, and France in particular was depicted as a nation occupying rightful Italian territory and a natural opponent of Italy, with the Napoleonic Wars often being cited by Italian nationalists as a justification for revenge on the French. With that being said, it was not like Italy really had a choice over its opinion on France. While the Entente had cared little for the Treaty of Vienna back in 1915, the Treaty of Budapest immediately destroyed any chances the Entente ever had at attempting to align with the Italian government. Instead, Britain and France became critics of Italy, and labeled it as a hostile state that threatened any potential Entente victory in the Great War.

One particular Italian man would take the nationalism born out of the Treaty of Budapest and take it to a horrific extreme that would permanently scar the entire world. Benito Mussolini had once been a socialist, and had even worked for the newspaper of the Italian Socialist Party, however, his nationalist views and desire to promote nationalist desires over actually benefiting any people would lead him to leave behind socialism and form his own new reactionary ideology. After the Treaty of Vienna, Mussolini became a strong supporter of a declaration of war on the Entente, and his new organization, the Italian Fasci of Combat (FIC), would reflect these views. Mussolini would blame the French Revolution and Marxism for the “mob rule” and shift away from a value on nationalism in Europe, and Mussolini believed that these views were only validated by the egalitarian views of the Russian Soviet Republic.

Therefore, the FIC quickly completely differentiated from socialism and became a different ideology altogether. Ultranationalism, reactionism, ultra-totalitarianism, militarism, and corporatism were all features of this new so-called “counter-revolutionary” ideology, and liberalism and democracy were quickly completely rejected as a threat to the preservation of a nation. Racial hierarchy was also promoted by Benito Mussolini early on, who believed that the French, and for that matter most Latin nations excluding Italy, had become inferior after succumbing to liberalism, and Mussolini despised the Slavs.

And thus, a new and sinister ideology was born, one that would plague the minds of millions and would slaughter even more. Our planet was ruined for decades by this one terrible idea, one that was arguably the biggest factor in the extension of the Great War by two decades. In the Italian parliamentary election of 1921, the FIC gained a handful of seats and would begin its climb through the ranks of Italian politics as the countdown to the conclusion of Italian neutrality and democracy started.

Fascism had been born.

Symbol of the Italian Fasci of Combat, and later fascism itself.

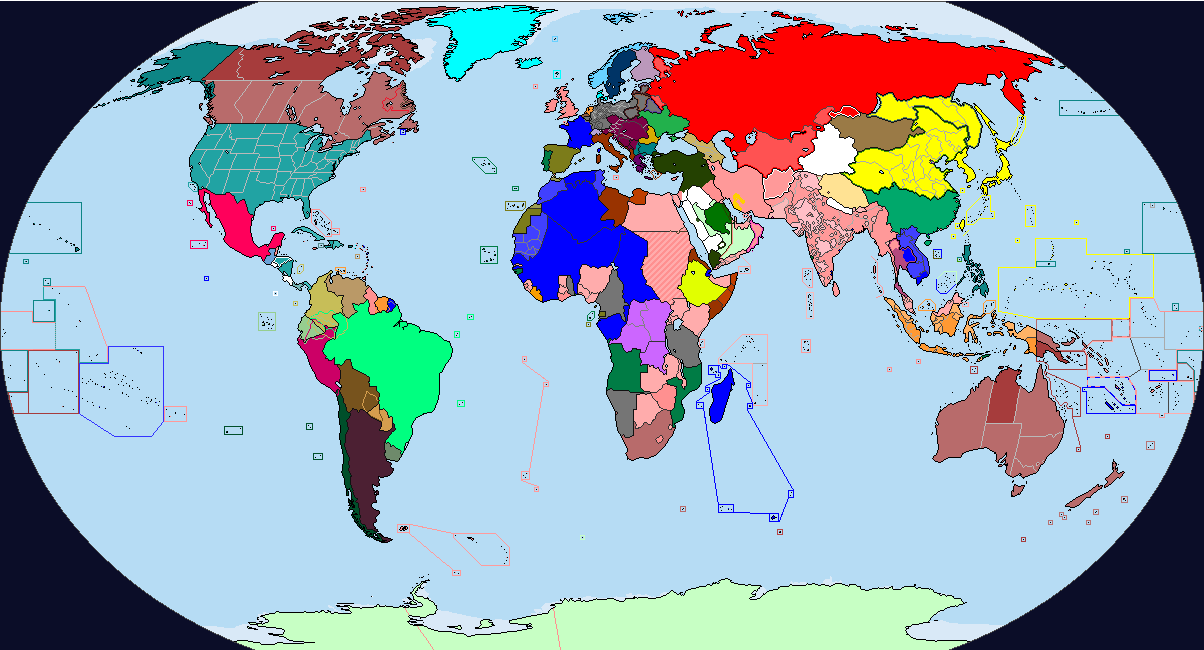

Map of the World circa March 1921.

“At long last, Japan has become capable of promoting a greater future for all of Asia. May the dawn of peace with Germany be the prelude to a greater peace on the Asian continent.”

-Japanese Prime Minister Inukai Tsuyoshi addressing a crowd in Tokyo following the Treaty of Fukuoka

Japanese soldiers in Vladivostok moving south to Korea, circa 1919.

When one focuses on the history of the early 20th Century, nearly all attention is ceded to the Great War. After all, the Great War was by far the bloodiest conflict ever fought in human history. With that being said, however, the history of the powers that maintained neutrality throughout the duration of the Great War is also incredibly important, especially when seeking out the origins of the post-war geopolitical climate. Therefore, it is necessary to delve into the history of the “sleeping giants” of the Great War; the United States, Italy, China, and Japan in order to completely understand what the politics of the world were like during the Great War.

After the Empire of Japan negotiated its removal from the wrath of the Great War with Germany, the Japanese government immediately shifted its attention to its western neighbor, China. As of recently, China had been the victim of plenty of violence despite not being involved in the Great War. In the December of 1915, President Yuan Shikai of the Republic of China was declared the emperor of the Empire of China in an attempt to bring stability to the rapidly deteriorating Chinese government. Yuan’s coronation, however, was met with retaliation from those who still supported democracy and put up resistance to the Hongxian Emperor (the new title for Yuan Shikai) as southern Chinese provinces seceded and forged the National Protection Army to fight against the Empire of China and restore the destroyed republic.

Yuan Shikai, the Hongxian Emperor of the Empire of China.

While the Empire of China initially appeared to have an advantage over the secessionist republican provinces in the south, the unpopularity of the Hongxian Emperor would severely harm the war effort. The independent provinces loyal to the National Protection Army somehow overcame their shortcomings due to the vast array of discontent within the high command of the Beiyang Army. As pressure to abandon the Empire of China grew, Yuan Shikai abdicated from his position as the monarch of China in the March of 1916, and on July 14th, 1916 the National Protection War ended with a victory for the southern republicans following Yuan Shikai’s death in the prior June. In the aftermath of the collapse of the Empire of China, numerous members of the Hongxian Emperor’s Beiyang Army became warlords, and China fell apart.

The National Protection War was merely background noise as the Great War raged on, however, the Japanese were especially concerned with the crisis to their west. The fates of Japan and China were intertwined, and cooperation between the two became increasingly precious once Japanese imperialism entered the Asian mainland. By the time the Empire of Japan left the increasingly destructive and chaotic Great War, National Protection War had concluded and China’s stability was rapidly deteriorating. While the Republic of China was restored, warlordism was increasingly rampant and the internal politics of the Chinese democracy were becoming more and more polarized. Under the leadership of Sun Yat-Sen, the nationalist Kuomintang rose to become the opponent of President Li Yuanhong and Premier Duan Qirui. It was apparent to all in China that the government of the re-established republic was on the brink of internal collapse, and all it would take was one spark.

Unfortunately for the Republic of China, that spark did come. General Zhang Xun, a staunch monarchist who was previously loyal to the Hongxian Emperor, would invade Beijing in the June of 1917 and forced President Li to dissolve the Chinese parliament, and restored the young Puyi of the fallen Qing Dynasty as the emperor of China on July 1st, 1917. Li Yuanhong and his supporters would evacuate north to Manchuria, where Duan Qirui was tasked with protecting the rapidly deteriorating Republic of China after defeating an attempt to restore the Chinese Qing monarchy in Manchuria. Due to bad experiences with the institution in the past, Duan Qirui would dissolve the Chinese parliament, which caused Sun Yat-Sen and his allies in southern China to establish a rival republican government in the hands of the Kuomintang.

And thus, the Chinese Civil War had begun.

Less than a year after Yuan Shikai’s Empire of China was defeated, China was engulfed in an internal war yet again as the Republic of China shattered apart into factions of warlords. The Kuomintang-led Guangzhou Government of the southern provinces and the so-called Tianjin Government (named after the city of Tianjin, where Li Yuanhong’s government consolidated power following the chaos in Beijing) found themselves opposed in a war for control of one of the largest and most ancient nations to ever exist. The two governments immediately set out to consolidate their power, with Duan Qirui installing relatives into positions of power within the Tianjin Government, while the Guangzhou Government consolidated power by becoming a one-party military junta led by Sun Yat-Sen.

Premier Duan’s tendency to put his relatives in powerful positions would only harm the stability of the government he was supposed to keep together. In the shadows of the Tianjin Government, enemies of Duan Qirui rose up and would push for taking power away from the ambitious man. Li Yuanhong would retire from the presidency early in the August of 1917 and was succeeded by his vice president, Feng Guozhang, who intervened in the crisis involving his premier by pressuring Duan Qirui to resign, although there was much discontent produced by Duan’s underlings in retaliation that could have very well led to the return of Duan Qirui had not he personally insulted President Feng following his forced resignation.

When the Chinese Civil War broke out in the summer of 1917, the world ignored the crisis in the east. After all, the conflict was nothing compared to the international catastrophe that was the Great War and therefore was of little concern to European, or for that matter, western affairs. The Japanese, however, continued to keep an eye on China as Tianjin and Guangzhou clashed, and many Japanese political officials were fearful that the civil war could potentially risk their dreams of Pan-Asian collaboration. In fact, the Chinese Civil War was one of the many factors that contributed to the Japanese and Germans sitting down for peace talks in Fukuoka, due to many in Japan desiring to intervene in the Chinese Civil War rather than waste lives and resources on the seemingly pointless and increasingly deadly Great War.

Upon leaving the Great War, Prime Minister Inukai Tsuyoshi shifted attention to China, and as the Russian Democratic Federative Republic stabilized Japanese soldiers were called south in preparation for any potential intervention in China. If Japan were to enter the Chinese Civil War, it was obvious which faction they would support. The hostile and nationalist Guangzhou Government would never become an ally of the Empire of Japan, and was anticipated to become a rival of the Japanese should Sun Yat-Sen and his Kuomintang emerge victorious over all of China. Furthermore, there were many pro-Japanese elements within the Tianjin Government, which would guarantee that diplomacy between the two regimes was not only possible, but would most likely go over well for the increasingly desperate Feng Administration.

In the November of 1919, the new premier of the Tianjin Government, Wang Daxie, briefly visited Japan and would speak in front of the Imperial Diet, imploring its members to support the Tianjin in its war against the Kuomintang. Wang’s diplomatic mission proved to be a success, and on December 2nd, 1919 the Japanese government, which had already been loaning resources to the Tianjin Government for awhile, agreed to deploy soldiers in China in order to fight the Guangzhou Government to the south. Within the next few days, history would accelerate as the RDFR would join its ally, Japan, in the Chinese Civil War and, soon enough, experienced Russian officers who had fought on behalf of the Green Army were fighting in China alongside the Japanese and Chinese. In order to consolidate an alliance, the three nations would meet in Tonghua to officially establish an official alliance. The Tonghua Pact, a mutual defense and free trade coalition, was formed on December 22nd, 1919, and ensured the cooperation of all three regimes (as well as the Japanese military occupation of the RDFR and Tianjin Government for the foreseeable future), while also becoming the first step towards the upcoming East Asian Co-Prosperity Sphere.

Step by step, Asia was moving closer and closer to a unified government.

Bloodshed in the Yangtze

“I remember the Yangtze River well. When I was a young man, fighting on behalf of Chinese democracy in the Tianjin Army, it was at the banks of the Yangtze where I saw the worst horrors of war firsthand and gazed into the eyes of death itself.”

-Premier Mao Zedong addressing the East Asian Diet, circa 1941.

Emblem of the Kuomintang, the supreme political party in the Guangzhou Government and its successor, the National Republic of China.

Once the Tianjin Government assembled a coalition of regional powers, the preparation for the long push south commenced. Of course, in order for the Tianjin Government to win the Chinese Civil War, internal stability would need to be accomplished first. Feng Guozhong would exit the presidency of China in the October of 1918, and was succeeded by Cao Kun following an election, while the Communication while the bureaucratic and labor unionist Communications Clique secured a majority of seats in the Tianjin Government’s parliament. It was uncovered that Duan Qirui had attempted to rig the 1918 Chinese elections in favor of his Anfu Club, however, such attempts were uncovered and Duan’s already collapsing political career shattered. With public support of Duan nearly annihilated, the disgruntled military officer would consolidate his remaining power in the provinces of Anhui, Shaanxi, Suiyuan, and Chahar and declare war on the Tianjin Government on January 8th, 1919.

Duan Qirui, the leader of the Anhui Clique.

Duan Qirui’s new Anhui Clique would not choose to realign with Sun Yat-Sen’s Guangzhou Government, therefore meaning that it would have to simultaneously defend against both Tianjin and Guangzhou. Japanese intervention in the Chinese Civil War was still nearly a year away, however, the severely weakened Anhui Clique could not take on both sides at once and is two rival factions were far more populated and better equipped. The province of Anhui was partitioned in half by the dawn of the April of 1919, while Tianjin Government turned its attention to what remained of Duan’s regime. The Anhui Clique was definitely a threat to President Kun (especially once a handful of pro-Duan military commanders defected), however, the Clique was no match to the Tianjin Government and would rapidly lose territory within months. Thus, on June 29th, 1919 the Anhui Clique would completely collapse and was reintegrated into the Tianjin Government, while Duan Qirui and a few of his most loyal officers would evacuate west, living out the rest of their lives in retirement in Xinjiang.

Therefore, when the Empire of Japan arrived in northern China, the Tianjin Government was a stable and moderately powerful member of the Tonghua Pact and was ready to progress south against the Guangzhou Government. Sun Yat-Sen had taken advantage of the distraction that was the Anhui Clique, and progressed both west and north. By the time the Japanese had declared war on the Guangzhou Government, the Kuomintang’s National Revolutionary Army (NRA) had nearly pushed the Tianjin Government completely out of the Anhui province, and if it wasn’t for General Sun Chuanfang, Jiangsu would have fallen into the hands of Sun Yat-Sen months ago and the Kuomintang would be invading Sandong.

Even though it had the strongest nation in Asia on its side, the Tianjin Government would be in a fight for its very existence throughout 1920.

Under the command of Hideki Tojo, the Imperial Japanese Army pushed for the Yangtze, hoping to contain the Guangzhou Government in the southern provinces. Thousands of veterans of the Great War, both Japanese and Russian alike, would progress deep into the Guangzhou Government, and by the start of the March of 1920, China was divided along the Yangtze River, where the two factions of the Chinese Civil War exchanged gunfire over Asia’s largest river. Not even Lu Rongting, the individual who had presided over the NRA’s invasion of Jiangsu, could cross over into the north and the same situation applied to his counterparts, who returned gunfire to him every single passing day.

As the Chinese Civil War shifted into a war of attrition, the two factions began to endorse a peaceful end to the bloody conflict. The leaders of the Tianjin Government had actually supported negotiations for awhile, and Sun Yat-Sen’s aggression had been the only thing preventing a ceasefire being applied. However, as the situation for a breakthrough by the NRA became increasingly more implausible (not only that, but the Tonghua Pact was investing more and more resources and if things stayed the same, Cao Kun would eventually be able to call himself the unifier of China) Sun Yat-Sen entertained the idea of a diplomatic end to hostilities. Increasing pressure from Lu Rongting and likeminded officers commanding along the southern banks of the Yangtze would be the straw that broke the camel’s back and on October 11th, 1920 representatives from both Tianjin and Guangzhou, as well as their respective allies, would arrive in Hangzhou to come to a peaceful agreement.

After half a decade of bloodshed, China was at peace yet again.

After days of negotiations, the two factions finally managed to come to an agreement. China would be partitioned roughly down the Yangtze River between two governments. In the south, the Kuomintang would be free to assert its authority and centralize whatever provinces it occupied, while the Tianjin Government would control the northern provinces, with the exception of Xinjiang, which had asserted its independence under the monarchist Yeng Zengxin, the very last remnant of the Empire of China. The two Chinas did, however, have to agree to give up the official name “Republic of China,” in order to avert disputes over which state was the true successor to the unified Chinese democracy.

In the south, President Sun Yat-Sen declared the National Republic of China (NRC), a one-party military junta clenched within the iron fist of the Kuomintang. The NRC was immediately quickly centralized, and Sun Yat-Sen was declared the South Chinese president for life. Once all political parties, excluding the Kuomintang, were banned in South China, political dissidents and rivals of Sun who refused to conform to his dictatorship, were forced into exile or would face imprisonment or even execution. The nationalist junta of President Sun would quickly begin its industrialization in the upcoming years, and upon the death of Sun Yat-Sen in 1925, his cronies would begin to clash over who would become the next president of the National Republic of China.

Flag of the National Republic of China.

In the north, the Tianjin Government would rename to the Provisional Government of China in accordance to the Treaty of Hangzhou, however, this term was short-lived. By the end of the October of 1920, a new constitution for the Provisional Government was approved and on October 29th, 1920 the Chinese Federation was declared, with its capital in Beijing. Just like the name implies, North China was a federal democracy, a move conducted in part to satisfy the numerous autonomous warlords and governors who had presided over their respective provinces throughout the duration of the Chinese Civil War. Cao Kun would lead the Chinese Federation as its first president until 1927, when he lost an election to the dominant Youchuanbu Party, which had governed the legislative assembly of North China since the election of 1918 back in the Tianjin Government. The Chinese Federation would adopt the flag of the Republic of China as its banner, which had been adorned by the Tianjin Government beforehand.

Flag of the Chinese Federation.

After the Chinese Civil War concluded and the ink dried on the Treaty of Hangzhou, the Chinese Federation and its allies would preserve the Tonghua Pact, which became the dominant peacekeeping force on the Asian government, especially whilst the great powers of Europe were distracted by their nightmarish inferno of a war. In the November of 1920, the Bogd Khanate of Mongolia became the fourth member state of the Tonghua Pact due to fears of a potential Soviet incursion, especially after Tannu Tuva fell to communism, becoming the Tuvan People’s Republic, a Soviet puppet state, near the conclusion of the Russian Civil War. Throughout the 1920s, the Empire of Japan would reduce its military presence in both North China and RDFR, therefore securing the autonomy of the two nations, however, Japanese military bases would always exist within the two states, especially along the increasingly militarized Yangtze River.

The history of Asia and Europe in the 20th Century were, in many ways, parallel to each other. One continent would enter the new century as the masters of the world, while the other entered as the servants of the other. One was plunged into an era of unimaginable horror and bloodshed, while the other moved towards a greater peace that would end previous chaos. And of course, one continent’s global domination would be absorbed by the other. As one sun set, another would rise.

Decision 1920

“Stronger than a Bull Moose”

-Popular 1920 presidential campaign slogan for Hiram Johnson

United States Capitol building, circa 1910.

The United States of America is notorious for staying completely neutral throughout all of the Great War. Aside from condemnation of controversial wartime activities, such as the sinking of the Lusitania or the Wehrstaat Declaration, and the selling of supplies primarily to the Entente, the United States would stay completely out of the mess that war the Great War. Of course, this was by no means unprecedented. Despite being considered a great power that rivaled even the greatest empires across the Atlantic Ocean, the United States had a history of not only staying out of foreign affairs, but also keeping other powers out of their own affairs in accordance with the Monroe Doctrine, which had been put in place for nearly a century when Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated one day in the June of 1914.

President Woodrow Wilson, the first Democrat to reside within the White House since the presidency of Grover Cleveland, had actually campaigned (and won) in 1916 with the slogan “he kept us out of war” and intended to continue to preserve American neutrality. Instead, President Wilson focused on domestic concerns throughout the duration of his second term, and his actions would often infuriate northern progressives, Republican and Democrat alike. Despite serving as a the governor of New Jersey prior to being elected president in 1912, Woodrow Wilson was actually born in Virginia and was absolutely a southern Democrat. It was Wilson who would institute segregation upon federal offices, and discriminatory hiring practices were only increased by the Wilson administration.

President Woodrow Wilson of the United States of America.

Economically, Woodrow Wilson was rather populist, however, it was his socially conservative ideology that would get him more attention. The racism of the Wilson administration would continue throughout his entire second term, however, his suppression of labor strikes, many of which were put down violently, became especially prominent as the 1920 presidential election neared. Feminism would also grow throughout his second term, however, Wilson and like-minded Democrats were keen on ensuring that the rights of women would be not determined by the federal government, but rather by local governments within the forty-eight states of the United States. This, coupled with the outbreak of a vicious disease, named the Kansas Flu, in 1918 would diminish the support of the Wilson administration.

By the time Woodrow Wilson’s second was nearing completion, the president was increasingly unpopular and there was no way the Democratic Party would nominate President Wilson for a second term. Not that Woodrow Wilson would run in 1920 anyway, his physical health was declining every day, especially after President Wilson fell ill with the Kansas Flu himself. Therefore, the Democratic Party would have to find a new candidate for the presidency, and plenty of men took up the challenge to win the support of one of the largest political organizations within the United States. While William Gibbs McAdoo, Wilson’s son-in-law, appeared to become the Democratic candidate, Woodrow Wilson suddenly took a gamble at being nominated for a third term by preventing McAdoo from winning the nomination. All this did, however, was doom McAdoo’s chance to become the next president and the Democratic National Convention selected Governor Carter Glass of Virginia instead, and Alexander Mitchell Palmer was chosen to be his running mate.

Carter Glass.

The Republican Party, the opponents of the Democrats, would retaliate to the socially conservative Glass by pushing for a progressive from former President Theodore Roosevelt’s sect of the party in order to win the support of progressives across the United States and paint the Democrats as a reactionary party that had stubbornly held back social progress for nearly a decade (which was not completely false, if it weren’t for the faction of progressive Democrats within the party’s ranks). Of course, more conservative members of the Republican Party were still present within the 1920 presidential primaries, most notably Governor Frank Orren Lowden of Illinois, however, the conservative policies of the Wilson administration pushed the progressives to the top and, following the death of Theodore Roosevelt in 1919, the former president’s personal choice, Senator Hiram Johnson won the support of the Republican National Convention, and Senator Irvine Lenroot of Wisconsin became his running mate.

The race for the White House had begun.

As the clock ticked down to the day Americans would select their next president, the complete contrast between Johnson and Glass became extremely obvious. While both men were opposed to American entry into the Great War, their similarities ended there. Economically, Hiram Johnson endorsed the anti-trust policies of the late Theodore Roosevelt and supported collective bargaining between labor unions and corporate leaders in accordance to his advocacy for direct democracy. Carter Glass used such policies as an excuse to label Senator Johnson as a socialist, a claim that was popular amongst the conservative sect of the Democratic Party, but seemed a bit more ridiculous amongst Republicans and moderate Democrats.

Socially, the two men were also opposites. Glass’ support of states’ rights would cause him to declare that he would leave the issue of female suffrage to local governments (like his predecessor), while Hiram Johnson eagerly endorsed gender equality as a way to win over plenty of American progressives with ease. Another major issue that the two candidates battled over was segregation. In order to not destroy all support he had in the southern states, Johnson never straight out endorsed pushing towards racial equality, however, he did announce his support of ending Woodrow Wilson’s policies of segregation in federal offices. Glass, on the other hand, was one of the strongest proponents of Jim Crow laws within the United States, perhaps even stronger than Woodrow Wilson himself. This support of segregation would lead Carter Glass to propose the implementation of nationwide poll taxes as a way to keep poor African-Americans from voting, although he painted such a proposal as a way to keep communists from potentially winning any elections, at a debate with Senator Johnson. To this, Carter’s rival would say, “I see, you seek to forcefully suppress the communists? Why don’t you ask Mr Brusilov how that worked out for him?”

Carter Glass’ controversial support of nationwide poll taxes to keep poorer Americans away from ballots was arguably one of the most harmful blows to his bid for the White House. Many moderate and liberal Democrats were deeply disturbed by such a proposal, which would cause a divide within the party. One prominent Democrat who condemned Carter Glass was Franklin Delano Roosevelt, the Assistant Secretary of the Navy in Woodrow Wilson’s cabinet, and prominent progressive Democrat. After Glass’ announcement of supporting nationwide poll taxes was in the headlines of national newspapers, Franklin D Roosevelt announced that he would not vote for Carter Glass, deeming him a man who “would rather see democracy die than lose power.”

Roosevelt’s bold statement would turn him into a new symbol for progressive Democrats and an enemy of the conservative faction of the Democratic Party. In order to guarantee that his administration was still supportive of Carter Glass, Woodrow Wilson would fire Franklin Delano Roosevelt late in the September of 1920, which only further infuriated Roosevelt and his sympathizers. After losing his job, Roosevelt concluded that the Democratic Party was little more than a corrupt cabal of southern conservatives, and would invite several moderate and progressive Democrats to New York City. It was here that these like-minded politicians left the Democratic Party to forge their own new organization, named the Liberal Party, on October 10th, 1920. The founder of the Liberals, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, easily managed to become his new party’s first chairman, which automatically won him national fame.

Chairman Franklin Delano Roosevelt of the Liberal Party.

Due to having numerous policies that resembled the larger Republican Party, as well as choosing to endorse Senator Hiram Johnson rather than run their own presidential candidate in 1920, the Liberal Party quickly earned the nickname “Little Republicans.” That is not to say, however, that the Liberal Party did not have its own unique platform. The Liberals endorsed national female suffrage and Chairman Roosevelt in particular pushed for social welfare programs to help benefit the less fortunate of the United States, and the Liberals were especially opposed to poll taxes, one of the primary reasons why the Liberal Party had left the Democrats to begin with. While the Liberal Party did not openly consider itself an opponent of segregation, arguing that dividing black and white Americans in society was an affair of the states, opposition to poll taxes would turn the Liberals into opponents of restricting the African-American vote. Overall, the Liberal Party could be considered an adherent to the ideology of social liberalism, which more or less accurately describes the views of nearly all members of prominence.

The 1920 presidential election was held across the United States on November 2nd. Voter turnout was substantially large, especially due to fears that a national poll tax under a Glass administration would potentially prohibit plenty of Americans from ever voting again. If one were to look at an electoral college map, it would resemble numerous elections dating back to 1880. The northern states were solid Republican territory, while the southern states belonged to the Democratic Party. The west coast, the region Hiram Johnson originated from, easily went to the Republican Party, although anything within the Mississippi River and the Pacific Coast was a bit more contentious. In the end, however, this region was primarily won over by the ticket of Johnson and Lenroot, and by the midnight of November 2nd, 1920, it was obvious to the United States who would succeed President Woodrow Wilson.

After eight years, a Republican would be back in the White House.

Electoral college map of the 1920 United States presidential election.

While a victory for Hiram Johnson had been typically anticipated, especially when Franklin D Roosevelt formed the Liberal Party, the most devastating losses for the Democratic Party was in Congress. It was here where the Republicans not only secured a majority in both the House of Representatives and Senate, but the Liberal Party won numerous previously Democratic seats, especially in the northeastern states. As the days until Johnson’s inauguration in March began to pass by, the president-elect would start to endorse cabinet positions. Democrats were almost completely excluded from the upcoming cabinet of the Johnson administration, however, Liberals and a diverse array of Republicans would find positions in the executive branch.

Leonard Wood, a military officer from New Hampshire and progressive Republican, was almost immediately chosen to be the next secretary of war while Elihu Root returned to the position of secretary of state, which he had held during Theodore Roosevelt’s presidency. Rumors of the nomination of Franklin Delano Roosevelt as the Johnson administration’s secretary of the navy would circulate, however, in the end Roosevelt chose to remain the chairman of the Liberal Party and the Liberal Admiral Joseph Strauss was chosen for the position instead. The moderate Republican Calvin Coolidge was chosen to be the attorney general under Hiram Johnson, however, the other cabinet positions were filled with mostly progressive Republicans, such as Senator Robert Marion La Follette of Wisconsin.

When Hiram Johnson was inaugurated to become the twenty-eighth president of the United States of America on March 4th, 1921, the United States Capitol building was surrounded by a vast crowd eager to witness the inauguration of Johnson firsthand. For it was obvious to the whole nation that a new era had come upon the United States, one of progressivism, welfare, and social progress. Women were almost guaranteed that they would have the right to vote by the end of the year, and surely enough the Nineteenth Amendment was approved less than a month into the Johnson administration, only to be succeeded by the more radical Equal Rights Act and Twentieth Amendment a year later. The masses of the American workplace celebrated as the advancement of their rights from the days of the Roosevelt administration had been promised to return. President Hiram Johnson would bring upon a new age of American progressivism, one that had not been seen for well over a decade.

The Democratic Party, on the other hand, was doomed to things far worse than anyone could have ever imagined.

President Hiram Johnson of the United States of America.

The Eye of the Hurricane

“Our nation finds itself within the center of a storm. I implore my successor to not succumb to this storm’s brutality, for I fear that this storm could blow down our nation with ease.”

-Italian Vittorio Emanuele Orlando’s farewell address, circa 1920

Flag of the Kingdom of Italy.

When the Great War began, the Kingdom of Italy had just barely managed to stay out of the bloodbath that had overrun the rest of Europe within just a handful of days. Prime Minister Giovanni Giolitti and his successor, Vittorio Emanuele Orlando, were keen on preserving Italian neutrality throughout the Great War, choosing to focus on the improvement of the Italian military in navy in case the Great War came knocking on the Kingdom of Italy’s door. As a consequence of the military buildup, by 1920 the Italian armed forces rivaled that of the belligerents of the Great War, and the Red Army was the only neutral military force in Europe larger than that of Italy.

Throughout all of Phase I, a desire for Italian irredentism, and therefore entry into the Great War, would only grow. Multiple Italian politicians, including members of Orlando’s Liberal Union, would encourage joining one side or the other of the Great War, however, as it became increasingly unclear which side would emerge victorious, the Italian people shifted away from purely endorsing the Entente, especially after the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk was signed. Besides, as the date for the negotiations guaranteed by the Treaty of Vienna. As the Germans became especially concerned with ending the war on the western front as quickly as possible, perhaps Italy’s opportunity to force whatever Rome wanted out of the Central Powers had arrived.

Surely enough, Austro-Hungarian and German diplomats would sit down with their Italian counterparts in Budapest on June 17th, 1920 to decide the fate of South Tyrol, Dalmatia, and Albania. The easiest territory for Austria-Hungary to cede to the Kingdom of Italy was Albania, which was technically not Austro-Hungarian territory to begin with. Instead, Albania was a nation that had fallen under total Austro-Hungarian military occupation after choosing the wrong allies in the Great War, and only a few Austro-Hungarian military commanders grumbled about the cession of Albania to the Kingdom of Italy. In accordance to the Treaty of Budapest, the Kingdom of Albania was transferred into the hands of the Italians as a protectorate with a local prime minister who would be overseen by an Italian governor-general, and King Victor Emmanuel III of Italy was crowned the king of Albania.

Flag of the Kingdom of Albania.

Other territory subject to debate via the Treaty of Vienna was more contested. Dalmatia was Austro-Hungarian land and had been in the hands of Vienna for quite some time, and it was therefore very embarrassing for Emperor Karl I to give up to the Kingdom of Italy. Still, ceding Dalmatia was nothing compared to the debate over South Tyrol and Trentino, the former of which was dominated by Germans while the latter was a valuable port to the Adriatic Sea for the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Neither would be easy to pry from Austria-Hungary, even if the German Empire would in many ways be on the side of the Italians in order to keep the western front as small as possible.

In the end, the Kingdom of Italy would get to control Trentino, but not the German-majority South Tyrol. The cession of Trieste, Austria-Hungary's most valuable port, was even more unlikely than South Tyrol, however, some territory to the west of Trieste was given to Italy as a compromise. The Kingdom of Italy was also promised Tunisia, Corsica, and a vague chunk of territory in southwestern France if the Central Powers managed to capitulate the French. A five-year-long non-aggression pact between all involved parties was also signed in order to ensure that Italian soldiers would not be pushing for Vienna anytime soon.

The Treaty of Budapest was by no means ideal for either party involved, however, the Italians mostly viewed it as a victory and backed down on further aggression towards Austria-Hungary. The public opinion of the Central Powers became much more positive in Italy, and Germany and Austria-Hungary began to be depicted as nations that honored their treaties, as well as Italian allies. The Entente, on the other hand, became a target for future Italian irredentism, and France in particular was depicted as a nation occupying rightful Italian territory and a natural opponent of Italy, with the Napoleonic Wars often being cited by Italian nationalists as a justification for revenge on the French. With that being said, it was not like Italy really had a choice over its opinion on France. While the Entente had cared little for the Treaty of Vienna back in 1915, the Treaty of Budapest immediately destroyed any chances the Entente ever had at attempting to align with the Italian government. Instead, Britain and France became critics of Italy, and labeled it as a hostile state that threatened any potential Entente victory in the Great War.

One particular Italian man would take the nationalism born out of the Treaty of Budapest and take it to a horrific extreme that would permanently scar the entire world. Benito Mussolini had once been a socialist, and had even worked for the newspaper of the Italian Socialist Party, however, his nationalist views and desire to promote nationalist desires over actually benefiting any people would lead him to leave behind socialism and form his own new reactionary ideology. After the Treaty of Vienna, Mussolini became a strong supporter of a declaration of war on the Entente, and his new organization, the Italian Fasci of Combat (FIC), would reflect these views. Mussolini would blame the French Revolution and Marxism for the “mob rule” and shift away from a value on nationalism in Europe, and Mussolini believed that these views were only validated by the egalitarian views of the Russian Soviet Republic.

Therefore, the FIC quickly completely differentiated from socialism and became a different ideology altogether. Ultranationalism, reactionism, ultra-totalitarianism, militarism, and corporatism were all features of this new so-called “counter-revolutionary” ideology, and liberalism and democracy were quickly completely rejected as a threat to the preservation of a nation. Racial hierarchy was also promoted by Benito Mussolini early on, who believed that the French, and for that matter most Latin nations excluding Italy, had become inferior after succumbing to liberalism, and Mussolini despised the Slavs.

And thus, a new and sinister ideology was born, one that would plague the minds of millions and would slaughter even more. Our planet was ruined for decades by this one terrible idea, one that was arguably the biggest factor in the extension of the Great War by two decades. In the Italian parliamentary election of 1921, the FIC gained a handful of seats and would begin its climb through the ranks of Italian politics as the countdown to the conclusion of Italian neutrality and democracy started.

Fascism had been born.

Symbol of the Italian Fasci of Combat, and later fascism itself.

Map of the World circa March 1921.

Last edited: