I do have some Native American provinces (more like client states with equal political representation with the provinces, though they have more domestic autonomy) and a lot of Native American land grants at the provincial level (quasi-reservations but closer to where they live, more like autonomous areas with political representation in the lower house). There's a whole special system of negotiations between the natives and the federal government since the federal government is the only allowed entity to negotiate treaties with them. Native Americans in my BNA have quite a bit of political clout.I'm absolutely down with both. That's why I said and/or.

You should definitely add the most complicated system of Native American reservations you can think of. Real reservations aren't overly complicated, but they can confuse people, and it shouldn't be hard to invent extra complicated and confusing ones.

However, I think the winners of this thread so far are Augenis and Tomislav Addai.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Making a confusing, overly-complex political system

- Thread starter Tsochar

- Start date

Max Sinister

Banned

The Romans had this tribus system where each tribus had one vote. So the richest tribus would vote first, the result was announced, and if e.g. after two thirds had voted there was a majority, the poorer folks had come for nothing. A bit like the Prussian three-class voting system.

Not necessarily fair, but after all, we want complicated, not fair, don't we?

Not necessarily fair, but after all, we want complicated, not fair, don't we?

Oh yes. It had a Major council who had started as the main legislature but then became hereditary and swelled to over 2476 members, totally impractical for running a country. So the main legislature became the Senate that consisted of sixty men nominally, along with another sixty elected officially on an extraordinary basis though in practice they were chosen on a regular timescale and differed only in that while normal senators were elected by the Major Council they were elected by the normal senators. In addition the Council of Forty were also members as were all venetian ambassadors and senior military commanders. Finally the meetings were presided over by the by the Full College, the effective executive arm of the Venetian government, which was in charge of preparing matters for discussion in the Senate through the Savii del Consiglio.I'm no expert, but I heard that the republic of Venice had a complicated system. Although it was more about the election process, which included lots.

The Full College (Venetian: Pien Collegio) was the main executive body of the Republic of Venice, overseeing day-to-day governance and preparing the agenda for the Venetian Senate.

The Full College comprised the Doge of Venice and the rest of the Signoria—the six ducal councillors and the three heads of the Council of Forty—as well as three sets of savii ("wise men") with particular responsibilities: the six savii del Consiglio, the five savii di Terraferma (responsible for Venice's mainland possessions), and the savii agli Ordini (responsible for maritime matters). As with other higher magistracies of Venice, restrictions were placed on the eligibility to the office for the savii: the members were elected from the Venetian Senate, served a term of six months, and could not be re-elected to the same office for three or six months thereafter. To ensure continuity, the appointments to the office of savio were staggered, with six-month tenures beginning on 1 October, 1 January, 1 April, and 1 July.

The College met daily, under the presidency of the Doge, but with the savii del Consiglio setting its agenda. The council read reports and dispatches, gave audience to foreign envoys, and prepared all issues to come to a vote before the Senate. On its own discretion, particularly on pressing matters of finance or foreign affairs, the College could instead send motions to be voted by the Council of Ten.

Within the college were the Savii del consiglio:

The savii del Consiglio ("Wise men of the Council"), also known as the savii grandi ("Great Wise Men"), were senior magistrates of the Republic of Venice.

The positions were created in 1380 to assist the councils comprising the government of the Republic. Their duty was to "prepare [the government's] agenda, frame resolutions, defend them, and supervise their execution". The savii, six in number, were chosen from the members of the Venetian Senate, or Consiglio dei Pregadi, whence their name. As with other higher magistracies of Venice, restrictions were placed on the eligibility to the office: the members served a term of six months and could not be re-elected to the same office for six months thereafter. To ensure continuity, the appointments to the office were staggered: three took office on 1 October, three on 1 January, three on 1 April, and three on 1 July.

The savii were always present in, and in charge of the agenda of, the daily deliberations of the Full College (the Venetian cabinet). They were also obliged to be present in all sessions of the Council of Ten that had to do with foreign affairs. Consequently, and since no proposal could appear for vote before the Senate without having first been reviewed by the College, the savii del Consiglio came to be part of a small core of officials who exercised the most control over the governance of the Republic, alongside the Doge of Venice, the six ducal councillors, and the heads of the Ten.

They assisted the Signoria

The Signoria of Venice consisted of:

- the Doge, head of the Republic

- the Minor Council (Minor Consiglio), created in 1175, which was composed of the 6 advisors of the Doge.

- the 3 leaders of the Criminal Council of Forty the supreme tribunal, created in 1179.

The Signoria was considered a very important body of government, more important than the Doge himself. The sentence se l'è morto el Doge, non l'è morta la Signoria (The Doge is dead, but not the Signoria) was ritually said during the ceremonies set for the death of the Doge.

Then came the Council of Ten

The Council was formally composed of ten members, elected for one-year terms by the Great Council. In practice, its sessions were expanded to 17 members by including the Doge and others of the Signoria. For major questions, the number could be further increased by summoning some number of additional Senators, who composed the zonta; however, this practice was rarely used after 1583.

Members of the Council could not be elected for two successive terms, nor could two members from the same family be elected simultaneously.

Leadership of the Council was vested in three Capi, who were elected from among the ten members for one-month terms. During the month in which they served, they were confined to the Doge's Palace in order to prevent corruption or bribery.

The Council was formally tasked with maintaining the security of the Republic and preserving the government from overthrow or corruption. However, its small size and ability to rapidly make decisions led to more mundane business being referred to it, and by 1457 it was enjoying almost unlimited authority over all governmental affairs. In particular, it oversaw Venice's diplomatic and intelligence services, managed its military affairs, and handled legal matters and enforcement, including sumptuary laws. By the end of the sixteenth century, the Council of Ten had become Venice's spy chiefs, overseeing the city's vast intelligence network.[1] The Council also made numerous, though mainly unsuccessful, attempts to combat vice, particularly gambling, in the Republic.

There was also a second spy group,known as the Supreme Tribunal of State Inquisitors, founded in 1454 established to guard the security of the republic. By means of espionage, counterespionage, internal surveillance, and a network of informers, they ensured that Venice did not come under the rule of a single "signore", as many other Italian cities did at the time. One of the inquisitors – popularly known as Il Rosso ("the red one") because of his scarlet robe – was chosen from the Doge's councillors, two – popularly known as I negri ("the black ones") because of their black robes – were chosen from the Council of Ten. The Supreme Tribunal gradually assumed some of the powers of the Council of Ten.

In addition there was The Council of Forty, or the Supreme Court of Forty, also known as The Quarantia was one of the highest constitutional bodies of the ancient Republic of Venice, with both legal and political functions as the Supreme Court.

By some estimates, the Quarantia was established in 1179 as part of the constitutional reforms that transformed the monarchyinto a communal form. It was established as an assembly of forty electors who were entitled at that time to nominate the Doge of Venice. These forty were elected in their turn by nine electors who were nominated by the popular assembly, la concio. After completing their primary role as the Doge's nominators, they remained in power alongside the Doge as the Judiciary, participating with the Consiglio dei Pregadi (Senate) in the state government and the legislative functions, which were often delegated to them by the Great Council, in which the forty were members by law.

After the constitutional reform of 1297, which, with the Serrata del Maggior Consiglio (Lockout of the Great Council), changed the state's form into an aristocratic republic, the Quarantia was responsible for the approval and the scrutiny of new appointments to the Grand Council and the Senate but also, according to Maranini, preparation of draft laws concerning criminal justice and fiscal management.

In time, the Quarantia lost its legislative and representative functions to the Council of Senate and around 1380, after the creation of the College of the Sages, its executive functions were largely taken away as well.

The Forty preserved as a result from that time the functions of governing the mint (defining the fineness of the coins, the nature and quality of the stamping), the preparation of financial and revenue plans to be submitted to the Great Council and, above all, the supreme judicial function. Forty judges were elected by the Great Council and held office for one year; they could be re-elected, and in case of a vacancy could co-opt new judges.

The Supreme Court was tripled over time to better meet the judicial needs, creating new Quarantie:

- In 1441 the original Forty took the name of Criminal Quarantia and a Civil Quarantia was put alongside it.

- In 1491 the Civil Quarantia became known as the Old Civil Quarantia and was joined by the New Civil Quarantia.

The Criminal Quarantia had jurisdiction over misdemeanors and felonies and in general over criminal law. The three leaders of the Forty sat beside the Doge and Minor Council in the Serenissima Signoria, the supreme representative body of the Republic. The confirmation of the Serenissima Signoria was necessary to give effect to the death penalty. The functions of prosecutorbefore this court were assumed by the Avogadori de Comùn.

Civil law

The Old Civil Quarantia had jurisdiction over issues relating to civil law limited to appeals from Venice, from the Dogado and the Stato da Mar. Access to their judgment was subject to prior scrutiny by the Auditori vecchi alle Sentenze, who in this case held the role of public prosecutor.

The New Civil Quarantia had jurisdiction over issues relating to civil law limited to appeals from the Domini di Terraferma. Access to their judgment was subject to prior scrutiny by the Auditori nuovi alle Sentenze and, in matters involving minors, by the Auditori nuovissimi, who in this case held the role of public prosecutor.

Finally there was the Doge, a mostly ceremonial head of state elected for life and subject to a great deal of regulation for example he was not allowed to pen correspondence from foreign powers without other magistrates witnessing it, he could not own property in a foreign land and to prevent the office becoming hereditary all his brothers and descendants were forbidden from sitting in any council save the Great Council or on any board except for two of his sons and one of his brothers who were granted an exemption and even they were stripped of their vote during the lifetime of their kinsman and limited to the Senate.

Spanish America was this. At the top of the specifically Spanish American hierarchy, you had the Council of the Indies, which acted as a court of appeal for all of Spanish American but only for civil cases which consisted of high amounts of money in dispute, or if the viceroy disagreed with the ruling of the colonial courts. It could also issue ordinances and had broad oversight powers over the Americas. This body varied over time, being fairly strong in the Hapsburg era, weakening during the initial Bourbon era, and This is fairly simple, but then we have more complexity.

Below this, we have the viceroyalties, each nominally ruled by a viceroy. Due to audiencias, colonial courts I'll get into in a second, they had little real power although this varied, they primarily executed laws, and since they were military men, they also served as commander-in-chief. Below the viceroyalties, there were a few captaincy-generals, ruled by captain-generals who had the same power of a viceroy, just in a smaller domain. Nominally, a viceroy was superior to a captain-general, but since both were directly appointed by the Council of the Indies and due to distance, the two were virtually independent of one another. There were also governors and below them corregidores, with the latter just being lower-level governors, and during the Bourbon era, intendants were appointed who controlled finance within an era. The rule of an intendant could be over multiple provinces, and they were used to centralize power to a massive degree. And they also listened to some civil cases, weirdly enough.

Talking about colonial councils, we primarily have audiencias, which were originally designed to be consultative bodies, but by the Bourbon era they were courts of final appeal (except for the ones to the Council of the Indies). Their rulings had to be adhered by the viceroy and captain-general, even if they disagreed. Furthermore, what a ruling consisted of was so vague that they also had a quasi-legislative power, but since Spain regularly issued compilations of the Law of the Indies, this was restricted. They also had quasi-executive power - for instance, new cities and settlements had to be accepted by them, tribute from natives was assigned by them, and they appointed judges and corregidores. Also, they put all administrative officials on a review at the end of their term through what was known as a residencia, and with this, an audiencia could exert even more power since with this review it could even imprison administrators. The nominal President of the Audiencia was usually the viceroy or captain-general, depending on who was in its city, but since viceroys and captain-generals were military men, they know nothing about law, and so the audiencia chose a Regent of the Audiencia to chair its meetings. This is except for the Audiencia of Quito, which had no viceroy or captain-general and so the audiencia just appointed a president. Also audiencias varied widely in size - some were unicameral and had single-digit numbers of judges, while others had separate chambers for civil and criminal cases. And the audiencia alone carried the royal seal necessary for some functions, and so that further established their power. To summarize - audiencias were primarily judicial, quasi-executive, and slightly legislative.

And below the audiencias, we have cabildos, municipal councils consisting of notables. But that's just your standard oligarchical municipal council.

Now, let's assume that there's no Peninsular War and so Spanish America remains loyal. Now, let's say Spain decides to democratize its empire. I would expect what they'd do is create legislatures co-geographical with the audiencias, which would also serve the purpose of making Spanish America divided and weak. These legislatures would have limited power to create laws, and I imagine all proposed legislation would need the royal seal, which means approval by the audiencia. Thus the audiencia would also serve as a sort of upper house, to be added to its various functions. Alternatively, or simultaneously, a democratized Spanish America could have the cabildos nominate/elect judges of audiencias. Thus, we'd have an indirectly elected body simultaneously judicial, legislative, and executive.

And it would be this administrative clusterfuck that would gradually become independent, assuming Spain is led by smart enough people to pursue gradual separation.

Below this, we have the viceroyalties, each nominally ruled by a viceroy. Due to audiencias, colonial courts I'll get into in a second, they had little real power although this varied, they primarily executed laws, and since they were military men, they also served as commander-in-chief. Below the viceroyalties, there were a few captaincy-generals, ruled by captain-generals who had the same power of a viceroy, just in a smaller domain. Nominally, a viceroy was superior to a captain-general, but since both were directly appointed by the Council of the Indies and due to distance, the two were virtually independent of one another. There were also governors and below them corregidores, with the latter just being lower-level governors, and during the Bourbon era, intendants were appointed who controlled finance within an era. The rule of an intendant could be over multiple provinces, and they were used to centralize power to a massive degree. And they also listened to some civil cases, weirdly enough.

Talking about colonial councils, we primarily have audiencias, which were originally designed to be consultative bodies, but by the Bourbon era they were courts of final appeal (except for the ones to the Council of the Indies). Their rulings had to be adhered by the viceroy and captain-general, even if they disagreed. Furthermore, what a ruling consisted of was so vague that they also had a quasi-legislative power, but since Spain regularly issued compilations of the Law of the Indies, this was restricted. They also had quasi-executive power - for instance, new cities and settlements had to be accepted by them, tribute from natives was assigned by them, and they appointed judges and corregidores. Also, they put all administrative officials on a review at the end of their term through what was known as a residencia, and with this, an audiencia could exert even more power since with this review it could even imprison administrators. The nominal President of the Audiencia was usually the viceroy or captain-general, depending on who was in its city, but since viceroys and captain-generals were military men, they know nothing about law, and so the audiencia chose a Regent of the Audiencia to chair its meetings. This is except for the Audiencia of Quito, which had no viceroy or captain-general and so the audiencia just appointed a president. Also audiencias varied widely in size - some were unicameral and had single-digit numbers of judges, while others had separate chambers for civil and criminal cases. And the audiencia alone carried the royal seal necessary for some functions, and so that further established their power. To summarize - audiencias were primarily judicial, quasi-executive, and slightly legislative.

And below the audiencias, we have cabildos, municipal councils consisting of notables. But that's just your standard oligarchical municipal council.

Now, let's assume that there's no Peninsular War and so Spanish America remains loyal. Now, let's say Spain decides to democratize its empire. I would expect what they'd do is create legislatures co-geographical with the audiencias, which would also serve the purpose of making Spanish America divided and weak. These legislatures would have limited power to create laws, and I imagine all proposed legislation would need the royal seal, which means approval by the audiencia. Thus the audiencia would also serve as a sort of upper house, to be added to its various functions. Alternatively, or simultaneously, a democratized Spanish America could have the cabildos nominate/elect judges of audiencias. Thus, we'd have an indirectly elected body simultaneously judicial, legislative, and executive.

And it would be this administrative clusterfuck that would gradually become independent, assuming Spain is led by smart enough people to pursue gradual separation.

Okay, here's an idea:

A lower house is supposed to represent the people, right? But the people keep electing politicians, and as we all know, politicians are no good.

So the lower house is split into the house of representatives, who are elected, and the house of the people, who are drawn by lottery. The latter cannot introduce or alter legislation, and they are subject to special rules, but they can vote on anything and they can raise any issue that they want on the floor.

And of course, we don't want sore losers of the electoral process to muck things up, so every living former lawmaker and head of state is granted a lifetime seat in the House of Elders, which functions as an extension of the upper house. Exceptions are made for impeachment and so on.

A lower house is supposed to represent the people, right? But the people keep electing politicians, and as we all know, politicians are no good.

So the lower house is split into the house of representatives, who are elected, and the house of the people, who are drawn by lottery. The latter cannot introduce or alter legislation, and they are subject to special rules, but they can vote on anything and they can raise any issue that they want on the floor.

And of course, we don't want sore losers of the electoral process to muck things up, so every living former lawmaker and head of state is granted a lifetime seat in the House of Elders, which functions as an extension of the upper house. Exceptions are made for impeachment and so on.

Nah. It's more complicated IOTl, where the Native American lands have overlapping regions with the states, and fuzzily defined partial sovereignty as "dependent sovereign nations". What you did was simplify it.I do have some Native American provinces (more like client states....

Now this is complicated. I read every word of this, and I don't understand it in the least. You lost me at the second set of senators. Near as I can figure, Venice must have invented a political office for every single person in town. And they needed to hire a bunch of spies to seek out any Venetian they missed, and then invent a political office for that person too.Oh yes. It had a.... blah blah blah blah gobbledegook....

Indicus and Tsochar, you too are doing a pretty good job. Perhaps Spanish America could add to its old system, a House of Representatives and the People, and a House of Elders holding all the retired politicians.

ninel

Banned

I had a similar idea exactly 4 months ago, kinda inspired by the political system of the French Consulate.So the lower house is split into the house of representatives, who are elected, and the house of the people, who are drawn by lottery. The latter cannot introduce or alter legislation, and they are subject to special rules, but they can vote on anything and they can raise any issue that they want on the floor.

The idea was to have a big lower house with its members chosen by sortition that would vote on bills proposed and debated by a small (like, 50 members) elected upper house.

Of course this system isn’t very confusing, except to people confused by how the lower house composition has nothing to do with political parties’ popularity.

Dont forget the National Assembly which sort of occupied a lateral role to the legislative yuanArguably, the five-branch republican Chinese system is/was needlessly complex....

Arguably, the five-branch republican Chinese system is/was needlessly complex....

Part of my inspiration, in fact. Many branches of government with an executive separate from all of them.

I'm not really clear on what kinds of checks the ROC has on its president, because it sounds like it has next to none.

Do you really think Jiang or Yuan were the type to put checks on their own power?Part of my inspiration, in fact. Many branches of government with an executive separate from all of them.

I'm not really clear on what kinds of checks the ROC has on its president, because it sounds like it has next to none.

The National Assembly in theory I think.Part of my inspiration, in fact. Many branches of government with an executive separate from all of them.

I'm not really clear on what kinds of checks the ROC has on its president, because it sounds like it has next to none.

Unfortunately, due to the state of emergency and the undemocratic nature of a ten-thousand year assembly its legislative powers are hereby placed in the hands of the president, a TRUE guardian of the people’s liberty.The National Assembly in theory I think.

Unfortunately, due to the state of emergency and the undemocratic nature of a ten-thousand year assembly its legislative powers are hereby placed in the hands of the president, a TRUE guardian of the people’s liberty.

Which has the effect of massively uncomplicating it to one man, one vote - the president is the man, and he has the vote.

Indeed sir! So instead the assembly will not be dissolved however a commision shall be established to regulate the business of the assembly as assisted by the legislative yuan except in cases relating to the occupied mainland territories which shall be placed in the hands of a joint committee of the legislative and judicial yuan with aid from the assembly which requires approval from all three and in cases related to the establishment of the government the control yuan shall have oversight.Which has the effect of massively uncomplicating it to one man, one vote - the president is the man, and he has the vote.

Tsochar, the whole lower house should be called the Parliament. Its members are officially split into the House of Representatives and the House of the People, but they all meet in the same house and vote together as one body. The upper house + the council of elders should be called Congress. The upper house without the council of elders is called the Popular House. The council of elders is called the Senate. The supreme court is called the senate, in lower case.

And China aside, what about other dictatorships, like North Korea and Iran? I understand Iran has a Supreme Leader and all the positions that you'd expect a democracy to have, but a flow chart of Iran's organization system shows all sorts of groups of people whose purpose is a total mystery to me.

And is it true that the Chinese National Assembly is elected by members of the regional assemblies who are elected by local politicians who are elected by the people, who are only allowed to vote "Yes" on whoever the party nominates?

And China aside, what about other dictatorships, like North Korea and Iran? I understand Iran has a Supreme Leader and all the positions that you'd expect a democracy to have, but a flow chart of Iran's organization system shows all sorts of groups of people whose purpose is a total mystery to me.

And is it true that the Chinese National Assembly is elected by members of the regional assemblies who are elected by local politicians who are elected by the people, who are only allowed to vote "Yes" on whoever the party nominates?

Dude, the Chinese Parliament is so large that they only meet for 2 weeks every year- and they spend the entire year preparing their agenda for that time.And is it true that the Chinese National Assembly is elected by members of the regional assemblies who are elected by local politicians who are elected by the people, who are only allowed to vote "Yes" on whoever the party nominates?

The Chinese Parliament has 1,900 more members than the total population of the smallest country on earth,Dude, the Chinese Parliament is so large that they only meet for 2 weeks every year- and they spend the entire year preparing their agenda for that time.

No idea how this would work or if it could work, but I reckon a medieval Kurultai based republic in the Steppes could be this.

A general understanding amongst the Steppes tribes that the majority concencus is sacred and authoratative, with the "governing body" in essence being formed and reformed when multiple Kurultai are in one area. Perhaps a class of representatives who go from tribe to tribe with the decisions of their local kurultai and to arbitrate when two different kurultai disagree/ bring in another representative to settle the dispute. The "upper tent" could be a concencus amongst the representatives (the Kurultai of Kurultais) which has supreme authority and gathers a few times a year.

(Apologies if I spelt Kurultai incorrectly, I am tired and on my phone).

A general understanding amongst the Steppes tribes that the majority concencus is sacred and authoratative, with the "governing body" in essence being formed and reformed when multiple Kurultai are in one area. Perhaps a class of representatives who go from tribe to tribe with the decisions of their local kurultai and to arbitrate when two different kurultai disagree/ bring in another representative to settle the dispute. The "upper tent" could be a concencus amongst the representatives (the Kurultai of Kurultais) which has supreme authority and gathers a few times a year.

(Apologies if I spelt Kurultai incorrectly, I am tired and on my phone).

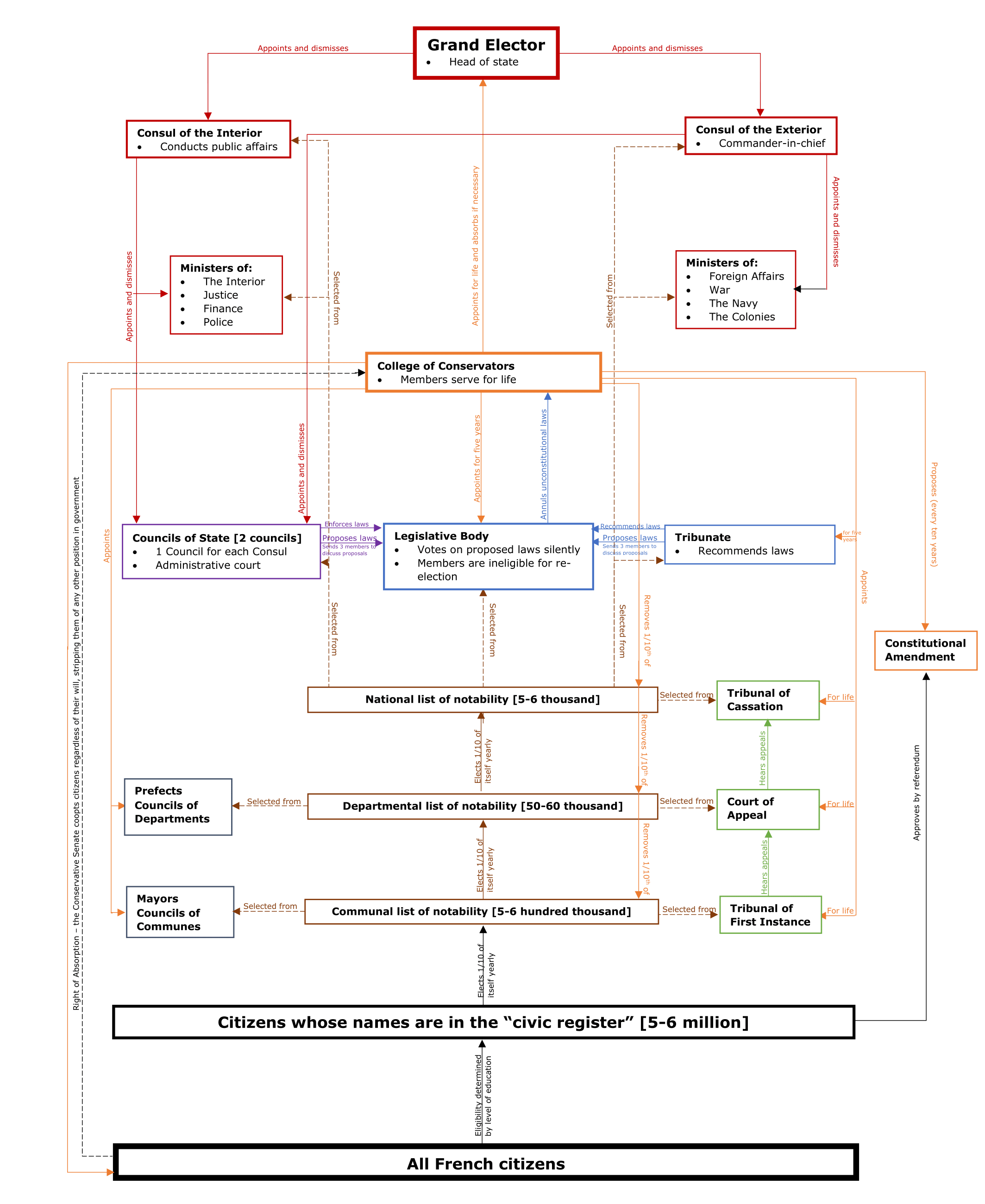

IOTL, the French Constitution of 1799 was extremely complex. But, oddly enough, it was based on an even more complex draft. A graphical model of this draft, written by Emmanuel-Joseph Sieyes, is below.

The core part of this constitution is the College of Conservators, a pseudo-aristocratic body which coopts new members through the right of absorption, whereby it could name a citizen to serve as a Conservator against their will (thus preserving the republic against the ambitious). This body plays numerous roles - it annuls unconstitutional laws, it names the members of parliament, the Grand Elector, and the judges from the lists of notability, and it amends the constitution every ten years. The other core part of the constitution is the lists of notability, where citizens whose names are in the civic register name candidates for the government to choose from. Note that the College of Conservators has the power to strike one tenth of the names off each list. The idea of lists was that by 1799, many French revolutionary moderates felt that elections would cause radicals or reactionaries to win, and so by only giving the people the power to nominate functionaries, moderates could always be chosen. Also, notably, this plan advocated aggregating communes into larger communes of similar size as an arrondissement would later be.

The executive branch consisted of a Grand Elector, a figurehead whose tenure for life, on the confidence of the College of Conservators. The Grand Elector is sort of like the president of a parliamentary republic, with no role other than as head of state and naming the cabinet. The top of the cabinet consisted of two Consuls, one of the Interior, directing internal affairs, and one of the Exterior, directing foreign policy and the military. These Consuls in turn name the other members of the cabinet, and the Consul of the Interior in particular has the power to name local administrators. Both Consuls name a Council of State, bodies which serve as administrative courts, draft regulations, and propose laws to be adopted (more on that later). Also, the selection process for a Grand Elector was very bizarre - the College of Conservators would, every year, hold an election for a potential new ballot, and contain the ballots from each of its elections in urns. The oldest urn was to be emptied every year, to ensure that there were always only six urns (for six years). Upon the death or absorption of a Grand Elector, the Senate would choose an urn, and the candidate with the most votes would become Grand Elector. If the leading candidate was dead, they were to be skipped over and the next highest candidate would be chosen. It was hoped such a procedure would ensure that the Grand Elector would be chosen without the intrigue of an election.

The legislative branch consisted of two bodies to propose laws, one the Councils of State representing the government, and the other the Tribunate representing the people. Each had the power to propose laws to the Legislative Body, a body which merely decided what proposed laws to ratify without speaking, and each body would send three of its members to argue their cases. In this way, the legislature is sort of like a court - two bodies proposing that their views be adopted by a silent body. And, of course, the College of Conservators can annul unconstitutional laws.

IOTL, Napoleon threw most of this draft out, but retained some of its institutions in a manner that ensured that he would have far more power a First Consul than the Grand Elector that this post replaced. Without Napoleon, perhaps more of this draft could be retained and we could see gradual democratization of this system.

The core part of this constitution is the College of Conservators, a pseudo-aristocratic body which coopts new members through the right of absorption, whereby it could name a citizen to serve as a Conservator against their will (thus preserving the republic against the ambitious). This body plays numerous roles - it annuls unconstitutional laws, it names the members of parliament, the Grand Elector, and the judges from the lists of notability, and it amends the constitution every ten years. The other core part of the constitution is the lists of notability, where citizens whose names are in the civic register name candidates for the government to choose from. Note that the College of Conservators has the power to strike one tenth of the names off each list. The idea of lists was that by 1799, many French revolutionary moderates felt that elections would cause radicals or reactionaries to win, and so by only giving the people the power to nominate functionaries, moderates could always be chosen. Also, notably, this plan advocated aggregating communes into larger communes of similar size as an arrondissement would later be.

The executive branch consisted of a Grand Elector, a figurehead whose tenure for life, on the confidence of the College of Conservators. The Grand Elector is sort of like the president of a parliamentary republic, with no role other than as head of state and naming the cabinet. The top of the cabinet consisted of two Consuls, one of the Interior, directing internal affairs, and one of the Exterior, directing foreign policy and the military. These Consuls in turn name the other members of the cabinet, and the Consul of the Interior in particular has the power to name local administrators. Both Consuls name a Council of State, bodies which serve as administrative courts, draft regulations, and propose laws to be adopted (more on that later). Also, the selection process for a Grand Elector was very bizarre - the College of Conservators would, every year, hold an election for a potential new ballot, and contain the ballots from each of its elections in urns. The oldest urn was to be emptied every year, to ensure that there were always only six urns (for six years). Upon the death or absorption of a Grand Elector, the Senate would choose an urn, and the candidate with the most votes would become Grand Elector. If the leading candidate was dead, they were to be skipped over and the next highest candidate would be chosen. It was hoped such a procedure would ensure that the Grand Elector would be chosen without the intrigue of an election.

The legislative branch consisted of two bodies to propose laws, one the Councils of State representing the government, and the other the Tribunate representing the people. Each had the power to propose laws to the Legislative Body, a body which merely decided what proposed laws to ratify without speaking, and each body would send three of its members to argue their cases. In this way, the legislature is sort of like a court - two bodies proposing that their views be adopted by a silent body. And, of course, the College of Conservators can annul unconstitutional laws.

IOTL, Napoleon threw most of this draft out, but retained some of its institutions in a manner that ensured that he would have far more power a First Consul than the Grand Elector that this post replaced. Without Napoleon, perhaps more of this draft could be retained and we could see gradual democratization of this system.

Share: