You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Look to the West Volume VII: The Eye Against the Prism

- Thread starter Thande

- Start date

Thande

Donor

Dear all,

Your regular update will be coming on Sunday as usual. However, I wish to make an announcement.

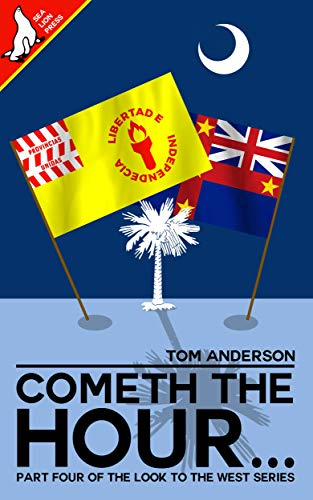

Look to the West Volume IV: Cometh the Hour... is available for pre-order on Amazon!

With yet another fantastic cover by @Lord Roem, as always.

It will formally be released on February 27th, just under a week from now, but you can get your pre-order in now. This one includes a number of bells and whistles such as excellent maps by @Alex Richards and flags and some other stuff by me. It was a long time in the editing so I'm glad to finally have it out there. I hope you enjoy it - and as always, I greatly appreciate Amazon or Goodreads reviews for either this or any of my other books!

Thanks to everyone for reading and commenting over the years!

Thande

Your regular update will be coming on Sunday as usual. However, I wish to make an announcement.

Look to the West Volume IV: Cometh the Hour... is available for pre-order on Amazon!

With yet another fantastic cover by @Lord Roem, as always.

It will formally be released on February 27th, just under a week from now, but you can get your pre-order in now. This one includes a number of bells and whistles such as excellent maps by @Alex Richards and flags and some other stuff by me. It was a long time in the editing so I'm glad to finally have it out there. I hope you enjoy it - and as always, I greatly appreciate Amazon or Goodreads reviews for either this or any of my other books!

Thanks to everyone for reading and commenting over the years!

Thande

Has the UPSA flag always looked like a chemical hazard sticker or is it just because it's got that gloss-effect overlaid on it? Either way, great news!

Will Vol. 3 paperback be avaliable soon too? I seem to recall it was. Only I'm worried I'm getting through Book 2 too fast.

Also does pre-ordering come with bonus features?

Also does pre-ordering come with bonus features?

Man. I know of those flags for Meridia/the UPSA and America/the ENA for so long they are like old friends.

....speaking of. Thande, Meridian was obviously the UPSA people’s name. Did “Meridia” ever form as a short noun from that? I don’t think I ever saw it in an entry.

....speaking of. Thande, Meridian was obviously the UPSA people’s name. Did “Meridia” ever form as a short noun from that? I don’t think I ever saw it in an entry.

It’s a torch with liberty and independence in SpanishHas the UPSA flag always looked like a chemical hazard sticker or is it just because it's got that gloss-effect overlaid on it? Either way, great news!

That brings up an ideaMan. I know of those flags for Meridia/the UPSA and America/the ENA for so long they are like old friends.

....speaking of. Thande, Meridian was obviously the UPSA people’s name. Did “Meridia” ever form as a short noun from that? I don’t think I ever saw it in an entry.

Did they ever come up with female anthropomorphic imagery?

That brings up an idea

Did they ever come up with female anthropomorphic imagery?

I believe they did in fact, though I can't for the life of me remember which entry would have it.

That brings up an idea

Did they ever come up with female anthropomorphic imagery?

I know the female personification of the ENA is called Septentria but can't remember where I read it.I believe they did in fact, though I can't for the life of me remember which entry would have it.

I know the female personification of the ENA is called Septentria but can't remember where I read it.

The WorldFest entry had it as part of a Statue of Liberty analogue.

Unveiled on the final day of the celebration (having been hastily worked on right up to the deadline) was the Temple to Civilisation, a great Neo-Classical pillar’d structure (already looking a bit out of date) topped with a great statue of Lady Septentria, the personification of the ENA equivalent to Britannia. She reached out with a sword in one hand and an olive branch in the other, a snake wrapped around her neck and body like a sash. Around her feet were the key dates in the Empire’s history: 1497, when John Cabot had sailed for England to North America for the first time; 1607, the establishment of the Jamestown Colony; 1751, when Frederick I had proclaimed the Empire; 1788, when it had received a Constitution and Parliament; 1828, when the Proclamation of Independence separated the Empire from Great Britain altogether; and now, the controversial numbers shining in the setting sun, 1857 – the year of the Constitutional Convention that had changed America forever.

Ah yes, truth! I forgot of Septentria.

I know she's meant to represent North America, but this being a world where *Dixieland split off from the *Northern USA gives "Septentria/North" a fun double meaning.

I know she's meant to represent North America, but this being a world where *Dixieland split off from the *Northern USA gives "Septentria/North" a fun double meaning.

Thande

Donor

I've avoided that term as an analogy for how Americans in this era of OTL tended to say "United States" on its own a lot as the name of their country, although probably some people have used it.Man. I know of those flags for Meridia/the UPSA and America/the ENA for so long they are like old friends.

....speaking of. Thande, Meridian was obviously the UPSA people’s name. Did “Meridia” ever form as a short noun from that? I don’t think I ever saw it in an entry.

Thanks for that, I was assuming the UK one would convert to the appropriate country for everyone automatically?

I am told this is being worked on, the main issue is it will probably need the chronology cutting either down or out in order to make the book a physically printable size. (Me and Brandon Sanderson, eh)Will Vol. 3 paperback be avaliable soon too? I seem to recall it was. Only I'm worried I'm getting through Book 2 too fast.

I am told this is being worked on, the main issue is it will probably need the chronology cutting either down or out in order to make the book a physically printable size. (Me and Brandon Sanderson, eh)

922 pages, amaright?

270

Thande

Donor

Part #270: Cash and Grab

“Yes, I know it was a bit of a forlor...I mean, a Finchley, Orpington, Rainham, Lewisham, Orpington, Rainham, Neasden, Hackney, Orpington, Pimlico...yes, you get the picture but what else could she... (long silence) She’s what? No, did I hear that right?”

*

From: Motext Pages EX512C-G [retrieved 22/11/19].

Remarks: These pages are listed under “SAAX Economic Studies Revision: Syllabus A (Economic History Module 2)”.

Extraneous advertising has been left intact.

The Panic of 1917, also called the Great Contraction, is probably the single most famous (or infamous) economic catastrophe in the world. This is despite the fact that many economic historians have spent much ink in arguing that there are far worse examples. Going back to the bubbles of the eighteenth century, the South Sea and Mississippi Company collapses (in Britain and France respectively) ruined a bigger proportion of very wealthy people. The tulip crazes in what were then the Dutch Republic and Ottoman Empire were more colourful (no pun intended) and extreme in terms of the rapid inflation of the arbitary value of a commodity. But then the world was less connected in that period. Arguably the first really global economic hit was the Panic of 1883, nowadays far less well known, but actually more damaging than the 1917 Contraction by some metrics. The 1883 decline’s original trigger was the eruption of Krakatoa in the Batavian Republic, which caused global cooling and widespread crop failures in a manner that had already been witnessed in 1816 with the eruption of Tambora, albeit less intense.[1] Poor harvests in both the UPSA and ENA impacted on European economies, and a number of banks collapsed and smaller countries defaulted at that time due to excessive speculation in the boom time. Unemployment was rife. Governments fell in democratic or partially democratic nations, often leading to a revolving-door situation as their successors proved no less capable at solving the underlying problems. The King of Greece was briefly forced to flee the country before returning with Italian help—after the shaky young Italian state narrowly suppressed violent mobs itself.

The Panic of 1883 led to the multinational Congress of Antwerp in 1885, in which the European and Novamundine powers adopted a convertible Electrum Standard and pegged their currencies to a fixed rate of exchange based on the commodities of both gold and silver.[2] This also led to increased regulation of banking and the setting up of more national banks, which some countries had already possessed. The so-called ‘Antwerp System’ persisted for a quarter-century until the Pandoric War, and limped on despite the latter’s upheavals for another seventeen years. During this time, there were many warning signs (noted by a few far-sighted economic commentators) that problems were mounting up and would eventually explode when triggered. However, there was a strong alienistic mood among the leaders of the nations that they desired a return to normalcy and the prosperity of the Long Peace, and they associated the Antwerp System with those halcyon days. In this, as J. P. Prendergast noted in hindsight (writing in 1942) they ‘confused cause and effect in the manner of a South Seas tribesman making a fetish of an aerodrome to bring back a flying visitor; the Antwerp System had came about as a consequence of the conditions required for that prospertiy—it had not created them’.

Because of this, both elected and hereditary leaders remained stubborn to suggestions that the rigid 1885 system needed modification or renegotiation to respond to the modern world. The debts racked up by the Pandoric War continued to circulate and grow through interest, often ending up ten or twenty steps removed from those who had incurred them. The English farce “Not Likely, That’s a Tree!” (staged 1915, phanty-filmed 1920) includes a prophetic joke about the fictional Tartary-adjacent Sultanate of Groovefunkistan (playing on contemporary Flippant slang words) which is said to owe a war debt of sixty million roubles to itself following a series of confusing exchanges.

===

===

But it would be a default on a very real debt that began the slide to the Contraction. In April 1917, driven in part by American frustration over delays in the construction of the Nicaragua Canal, the Kingdom of Guatemala missed a payment on the newly accelerated schedule of paying off the reparations she had been charged in 1899. There was promptly a public run on the Bank of San Salvador and the Guatemalan Army mutinied when King Felipe ordered it in to restore order in the capital. Mexican and American troops would move in to restore order and Felipe had regained his throne three months later, but by that point the global economic fuse had been lit by this first spark.

If it had not been Guatemala, it would likely have been Corea, which suffered a public uprising in late May and bank runs of its own. The elderly and out-of-touch King Geongjong had controversially imprisoned the reformist politician Lee Chang-jung, who had criticised Corean corporations in southern Yapon and India for making great profits whilst escaping taxation that might help the poor at home. The Corean public revolt alarmed both the Russians and Chinese, but it was the Chinese who came in to restore order, considerably reducing Russian influence in the peninsula. Some Corean nobles and other wealthy men briefly fled the capital of Hanseong [Seoul] in the face of public rioting, mostly going to the Corean colonies in Yapon. These found themselves shut out of returning, as one of the High State Counsellors cut a compromise deal with the released Lee to seize those men’s assets in return for leaving the rest alone.

These incidents, which could have been managed in isolation, caused global jitters and uncertainty which tipped all the trembling pots of stored-up war debt problems over the boil. “When America sneezes, Europe catches the flu” (today much modified with other examples) was coined by the Mount-Royal stockbroker Merton Bowers during the Panic. Countless loose ends had been created by the Societist Combine effectively writing off the debts of the old UPSA one way or the other, managed inconsistently since then. The Combine had refused to participate in the global economic system per se, carrying out more limited trade on an individual basis whilst working towards what Alfarus called ‘udarkismo’ (autarky, given an excessive Novalatina over-translation to sound new and exciting). This policy of self-sufficiency was not, as some pre-Iversonian conspiracy theorists would have it, proof that the Contraction was engineered by the Societists as part of their diabolical plan for world domination and one which they had prepared for. Rather, it was a move driven by the ideological desire to avoid ‘contamination’ by too much interaction with ‘the nationalistically blinded’. This is a position which arguably draws descent from Jean de Lisieux’s desire for buffer marches to ‘protect’ France from outside voices as he sought to change it to his nightmarish vision.

Given South America’s limitations in some resources, even with the addition of the East Indies and a large chunk of Africa, the ordinary Amigos and Amigas of the Combine were decidedly living in what Sanchez had called ‘equality of necessity’ in order to pursue this model of self-sufficiency for the ‘Liberated Zones’. However, this did mean that the Combine was more resilient in the face of the global crash as ‘it flung its tentacles destructively across the world like the final thrash of a dying octopus’ in the pithy words of Jacques Benoist. Russia also had the certain advantage of reliance on internal markets, though there was still widespread unemployment and the occasional food riot. In November 1917, Tsarevich Paul won plaudits from the people by imposing a one-off super tax on the RLPC’s profits for that year in order to subsidise new bread and potato rations. When he succeeded his father as Tsar two years later (though he had already been the real power at court for years) it would be as a man who enjoyed considerable popularity from his subjects—at the expense of deep suspicion from the Company men, a suspicion which would be deepened by his later actions.

France, on the face of it, should have been a country to suffer greatly from the Contraction. She was certainly not self-sufficient, and had built up a strong economic and military position that was highly reliant on a delicate web of connections across the world—based on the foundation of the Antwerp System. However, France had the advantage of a highly effective and dynamic government that enjoyed considerable public support. Robert Mercier had been in power as Prime Minister since 1905, winning three elections for his Diamantine Party amid the opposition Nationals struggling to find an effective counter. Philippe Soissons had succeeded Leclerc to lead the party into the 1910 election and had only lost further ground. Bertrand Cazeneuve had reversed that retreat, but Mercier continued to command a strong position in the Grand-Parlement.

This was despite the fact, as was an open secret to many in Paris (but not the wider kingdom), Mercier was a very ill man. His health had suffered considerably from a bout with the flu that had swept the world in the closing stages of the Pandoric War, theorised to be caused or exacerbated by the unprecedented global movement of soldiers. Though he had recovered from that, it had weakened his constitution and ever since, he could have months of strength and vigour followed by days or weeks of being bedbound for no apparent reason.

The fact that France nonetheless continued to be run consistently and well throughout his premiership was noted by those in the know (the wider people were successfully fooled by a variety of means into not suspecting Mercier’s condition). This was due to a number of reasons: Mercier’s mind did not suffer along with his body and modern communications meant that he could dictate orders from his bed via Lectel and quister; unlike the effective but Passeridic-managing Leclerc, he knew when to delegate; and, most importantly, there was his wife.

Heloise Rouvier had met and worked with Robert Mercier during the Pandoric War, in which she had assisted him in his role as Foreign Secretary. Rouvier had even taken over from Mercier in his first bout of illness, and had helped negotiate the postwar treaties with the Russians in particular. A strong-minded National Cytherean who idolised Leclerc’s mother Horatie Leclerc (nee Bonaparte), Rouvier was spoken of as rising higher than any female French politician ever had (unless one counted the rather unofficial role of Madame du Pompadour in the eighteenth century). This was all the more impressive considering only one in five Frenchwomen had the vote at this point.

However, Rouvier had been passed over for the role of Foreign Minister in favour of the less capable Soissons, in part thanks to her gender and (at that point false) rumours that she had fallen in love with Mercier. Some have portrayed her temporary retirement from politics and later marriage to Mercier as almost an act of spite, but this is to do her an injustice. Heloise Mercier did switch to the Diamantine Party and be elected as a parlementaire in her own right from that body, but she never compromised on her personal convictions and was always regarded as being on the doradist wing of the party.

During her husband’s tenure as Prime Minister, Heloise was frequently a go-between when he was in his bedbound state; many did not realise that (with his agreement) when he was too ill to make a decision, she would make it for him. Even when he was able to do so, he discussed the matters with her and took her advice. France was unofficially being run by a married couple, and sometimes by the wife alone. It was the sort of thing that had happened many times in the royal corridors of power, yet was a radical notion for democratically elected governance.

Historians disagree on just how much of France’s response to the Contraction can be attributed to Robert and how much to Heloise. Certainly, his periods of illness were scarcely closely documented for security reasons. Camille Rouillard, the Foreign Minister, also played a role; the actual financial role of Controller-General was held by Cedric Bouchez, a nonentity Diamantine grandee who had needed a top job in order to secure the support of his uncle’s old faction within the party. Regardless, the French government’s actions were swift and ruthless. France’s influence on other countries was rapidly deployed, with nations such as Spain and Autiaraux seeing public protests at taxes and tariffs imposed that would benefit French producers. There was also a mass sell-off of French state assets in India, a process that took inspiration from the Privatisation of Bengal but was achieved in a more gradual and measured way. The Maharaja of Mysore, Chamaraja Wodeyar XII, regarded this with alarm. Not unconnectedly, his people took note of the drawing-down of French military power in the region.

This policy was carried out with sufficient effectiveness that, though it burnt countless bridges and gave a number of countries and people new grudges against French, it allowed the government to manage the effects of the crisis without letting the hammer fall on the ordinary people of France (i.e. the electorate). Some historians highlight this as a key moment in the return of the values of the Democratic Experiment era, which had been partially suppressed by the so-called ‘Federalist Backlash’ in many countries. The mismanagement of the Great American War on all sides thanks to the erratic nature of democratic government had provided much ammunition for those who sought to limit its power. However, ‘La Mitigation du Mercier’ provided a (relatively) positive example of how democratic governments being beholden to their people could function. The spectre of revolution had never reared its head because the government had a vested interest in ensuring that the people be spared the worst of economic chaos, unlike the disaster of 1794.

===

===

Of course, the effective French response was only possible because France could call upon resources and influences far beyond her metropole. The same was not true of many of her neighbours. Having stabilised her own finances, France was now able to exploit this from a position of relative strength, as did Russia and, to a lesser extent, China. At this point Italy was suffering from the reign of a group who were half a radical Mentian revolutionary organisation and half an organised crime syndicate; the Armata Rossa or ‘Red Army’. Probably descended in part from the old Neapolitan Camorra, the Armata Rossa had a significant role in government corruption, wanting its own men on the take in positions of power—and assassinating those who got in the way.[3] With an ineffective federal government in Rome and a compromised regional one in Naples, the economic crash hit Italy particularly hard and almost broke the country in half, just as the Panic of 1883 had. However, France helped stabilise the situation by contributing elite counter-insurgency troops fresh from the failed attempt to suppress the Dufresnie uprising. There were a number of high-profile arrests and shootings of Armata Rossa commanders in the south.

England, Germany, Belgium and Danubia also suffered from the crash. England was generally able to sort out her own affairs with only a little economic aid from France, but this did lead to the English Gendarmery outlasting its promised abolition date due to its usefulness in exerting the Government’s will (and, indeed it is around to this day). Germany was perhaps the most famous case of French intervention being key. The otherwise popular Hochrad government of Fritz Ziege saw its first real setback when inflation set in from the repeated devaluation of the Bundesmark in an attempt to lubricate the wheels of trade. It was a measure of desperation in 1918 when the Ziege government agreed to a bail-out package for the Dresdner Bundesbank from the Banque Nationale Royale. This came with a humiliating price; the French government seized the assets of the iconic Meissen porcelain factory near Dresden as insurance. In the meantime, production was managed by the Sant-Gobain company, which also owned France’s own Sevres porcelain factory.[4] This move weakened Ziege’s popularity, and he chose to retire in 1919, replaced as Federal Chancellor by fellow Hochrad Wolfgang Ruddel.

Crucially, France’s moves never targeted countries in such a way that their armed forces would be weakened. If this was, in some ways, a continuation of the actions the belligerents of the Pandoric War had described as being those of a ‘French Vulture’, they also fitted into a wider framework. Leclerc’s Marseilles Protocol had largely failed with the embarrassment of the war in South America, but the Merciers sought to rebuild its basic intensions with a more direct goal in mind. Russia was seen as the biggest threat to French hegemony and world peace, and France needed military allies—or, failing that, a ‘Bouclier’ or shield to put between Petrograd and Paris.

Not all countries accepted French help. Belgium, France’s historical enemy, resolutely rejected what the ageing King Maximilian IV described as ‘the outstretched hand of that foul harpy with poison on her nails’. (It is unclear whether he was referring to the female anthropomorphic personificaton of France, Gallica, or Heloise Mercier, whom he is known to have detested on a personal level). Belgium had been swinging from crisis to crisis for fifteen years, with the United Radicals taking power in the national States-General in 1902, but being frustrated by the more conservative States-Provincial blocking reforms on the King’s orders. The so-called ‘Belgian Party’ had returned to power in 1913 out of sheer public frustration with the gridlocked status quo, but had done so just in time to take the blame for the Panic of 1917. Fundamentally, up till now the Belgian people had been annoyed with their erratic and overly authoritarian royal governance, but had done so from a position of comfort and prosperity. The war with Germany might have been fought for the sake of a handful of pointless money-drain colonies that were promptly lost to the Societists anyway; it might be unwise to joke about this lest the Police Royale Secrète hear about it; but few lives had been lost in the conflict and bellies were still full. The Panic changed that, and now for the first time in decades, there were food riots in the streets of Brussels, Antwerp and Amsterdam.

It is ironic that, at a time when the old Dutch Republic could perhaps have been recreated off the bank of public anger, the exilic Dutch republics in exile had all fallen to Societist control only a handful of years before. Historians disagree, regardless, on how much of the old Dutch identity still existed as a coherent political force at this point; the Wittelsbach culture-war policy of persecuting the remaining francophone Walloons (and to a lesser extent the Westphalian Germans) had tended to weld together the former Flemings and Dutch. Religion remained a divide, but though the King was Catholic, pillarised tolerance of both faiths (and representation of both in the wealthy establishment) had been the norm since reforms of the 1860s.

===

===

No, the biggest divide in Belgium was between rich and poor. When the States-General election of February 1918 produced a big win for the Belgian Party, the people knew the King had panicked and rigged it. A mass revolt ensued, the biggest European revolution since the Portuguese Revolution of almost seven decades earlier. PRS snitches were hanged from luftlights and their headquarters torched, town halls were seized, officials fled to loyalist areas such as Ghent and Luxemburg. Luik (formerly Liege), always a heartland of riot and rebellion in Belgium despite racial purging, became the rebel headquarters.

In the wake of this, French (and/or German) forces almost crossed the border if only to restore order. However, on April 4th 1918 the King confronted rebel forces at Antwerp. The same pleasant streets that, thirty-five years ago, had played host to the conference that had ended the Panic of 1893, were now stained with blood. Russian special forces, including elite Yapontsi ‘nindzhya’ troops, gunned down the Belgian rebels as both Belgian and Russian aerodromes bombed the barricades with death-luft from above. Europe watched in shock as Wittelsbach rule was ruthlessly restored, one town at a time, with much of the great historical Belgian heritage of art and architecture going up in flames in the process. Many refugees fled to France, invoking the Malraux Doctrine, or to Germany. By September 1918, Maximilian IV was firmly back on the throne—but with Tsarevich Paul’s hand on his shoulder. Maximilian proceeded to die only two years later, and his son Charles Theodore III was very much a Russian puppet. The European situation had changed radically.

Some historians criticise France for not intervening at this point. Besides the ongoing economic troubles, the primary reason for this is that Robert Mercier finally passed away in mid-April 1918, at the height of the crisis. King Charles XI (who had succeeded his father six years ago) wanted to appoint the grieving Heloise in his place, but once again prejudice in the Grand-Parlement made it unworkable. Instead, Rouillard became Prime Minister, but Heloise was kept on as the first female Controller-General[5] and continued the economic policies she and her husband had pursued. Rouillard is sometimes portrayed as an Areian villain in popular histories of Heloise’s life for this reason, but in fact the two liked and respected each other. Rouillard’s reputation is highest in his native Brittany, which enjoyed a resurgence in its language and culture thanks to his internal policies (which some have called proto-Diversitarian).

Given the ‘Bain-de-sang belge’ (Belgian Bloodbath) it is small surprise that people in this era regarded Russia rather than the Combine as a bigger threat to world peace. Russia also intervened in less destructive ways, with big loans to bail out both the restive Ottoman Empire and Persia, whose government had overspent without realising it thanks to low-level corruption. Russia attempted to make aid to California contingent on further concessions to bring the Adamantine Republic into a Russian orbit, but with only limited success (not least because California’s effective government also weathered the economic storm well). At this time, China took on many of the overseas Corean assets that no longer answered to its more cobrist government, expanding Chinese reach in India and southern Yapon. France’s primary intervention in the East came with help for Siam (a deal brokered by the Refugiados in the Philippines) which, again, was related to the ‘Mercier Doctrine’ of foreign policy which would set the stage for the Black Twenties. Mercier had believed that the lesson of the Pandoric War was that the only country that had the resources to stop Russia in a long war was China. His Eastern policy (continued by the new Foreign Secretary Vincent Pichereau) was intended to remove obstacles that would stand in the way of China focusing on Russia in such a war. Therefore, help to Siam was aimed at directing Siam away from a war of revanche for recovery of the lost parts of Tonkin, which would force China to fight on two fronts. The Siamese were suspicious, their history teaching them about unequal deals with France,[6] but for now it seemed the ploy might work.

Danubia was one place where something unexpected happened. Despite the relatively indirect way in which elections worked there, a decisive election result occurred in 1918 which saw the elevation of a plurality of Societist representatives to all four primary Volksrats. Precisely how this happened has been massively debated ever since. The Combine is known to have operated infiltrators across the world making moves from the shadows towards Alfarus’ ends (which does not necessarily mean backing local Societists). Because the elevation of the Vienna School was ultimately a bad thing for the Combine, the latter would later deny all involvement in the election result and censor the records, meaning finding the truth has become difficult. On the other had, it is certainly true that many Diversitarian narratives simply find it hard to accept that anyone would knowingly elect Societists, so perhaps that straightforward answer has been neglected.

Regardless, this led to a period of political paralysis in Danubia, but eventually the Grey Societists were accommodated in government. The people’s claimed motivation was that they wished the armed forces budget to be cut in order to free up funds to respond to the crisis, to help those who had lost their savings, etc. This was achieved to a limited extent, and Danubia was shifted towards a more ‘Bavaria-like’ neutral foreign policy, without embracing full Societism. This, indeed, was what Alfarus had feared when he had instituted his ‘udarkismo’; the purity of Sanchez had been corrupted by the everyday filth of compromise for the merely ‘immediate’ public good.

===

===

And what of the ENA, whose ‘sneeze’ had started all this? America had some of the same advantages of Russia or China, with vast internal markets that were less vulnerable to a global trade slowdown. However, President Tayloe’s government was already in decline by the time the crisis hit, and his response to it was far less competently handled than in countries like France or California. Indeed, Tayloe tried to blame everything on overspend by the late President Faulkner’s ‘Social American’ programmes (a commonly invoked scapegoat) and then attempted to slash them to curb the deficit, a move strongly opposed by the people and their representatives in the Continental Parliament. If anything, most economists now believe Faulkner’s somewhat isolationist policies and retreat from empire meant the ENA was now in a better place to weather the storm. He had also inadvertently helped Guinea and Bengal, which had more room for manoeuvre without being as closely tied into the Hanoverian trade system, and were able to gain more local influence with their neighbours as a consequence.

The 1918 American general election was a decisive victory for the Liberal Party, who almost won an outright majority and were able to govern effectively with the Mentians as coalition partner. Michael Briars, the now-ageing Liberal grandee who had lost out to Faulkner in 1900 and then been defeated for the leadership by the younger Michael C. Dawlish in 1908, had finally gained the leadership in 1909—only to then lose the general election to the incumbent Tayloe in 1914. Appropriately enough, perhaps, he was replaced by someone who traced his political identity from a similar story of losing out. David Fouracre III was the grandson of Sir David Fouracre, who had served in the Great American War and whose son had traded on his name in an attempt to win the Liberal leadership in 1875 on the death of Albert Braithwaite. David Jr. had been defeated by Michael Chamberlain, who had gone on to become one of the greatest Liberal Presidents. But in the next generation the Fouracre family of Buenos Aires, Erie Province, Pennsylvania finally had its shot at political glory.[7]

In the short term, Fouracre followed the advice of the economist Gordon Hareby, who argued that it was possible for a government to spend its way out of a depression through infrastructure spending to grow the economy.[8] (For more detail, see Economic Theories Module 1). This led Fouracre’s government to quickly finish the Nicaragua Canal, despite the Societists having built their own canal first, and embark on a number of other projects that would boost employment at the expense of further borrowing. Fouracre’s approach remains controversial to this day, but it is certainly true that many American roads, railways and public buildings would not exist without his ‘New America’ programme. Then and now, particular controversy attaches to the fact that many desperate poor workmen were often sent into dangerous situations for the sake of that infrastructure building, meaning Fouracre’s New America is generally seen as colder and more impersonal than Faulkner’s Social Americanism. Fouracre is generally portrayed as caring more about numbers than people.

In summary, then, the Panic of 1917 not only had a drastic impact on the lives of people around the world but severely weakened the old Electrum Standard, with many countries removing their currencies from the specie exchange system. It was joked at the time that the French livre was ‘backed by steel’, i.e. French military power meant that few would dare to call in their debts when the Merciers were trying to juggle too many balls of debt and keep them in the air at once. This was certainly also true of the Russian rouble. It was in this era that paper money, which had previously been circulated only temporarily and in times of war, became the norm.

Perhaps most importantly at all, however, the Panic also set in motion or accelerated many of the trends which set the scene for the Black Twenties. After countries such as Germany and Italy had tried to break out of the Marseilles Protocol following France’s embarrassment in South America, the response to the Panic meant they were now firmly once there again. French policy had changed, being somewhat less domineering and more seeking anti-Russian allies; but nonetheless, bridges had been burned...

[1] In OTL the 1883 Krakatoa eruption’s impact on crop harvests was relatively muted; in TTL, though the eruption itself is the same, the weather patterns are very different after over 150 years of divergence, and the effects are more severe (though still not on the level of the 1816 ‘Year Without a Summer’).

[2] The ‘Electrum Standard’ is so called because electrum is an alloy of gold and silver; we would just call it a bimetallic standard. Unlike OTL, there is no push for a single Gold Standard. This was driven in OTL by the economic heavyweight of Britain pushing for a gold-based recoinage following the debts of the Napoleonic Wars and a silver shortage caused by revolutions in South America and the China trade absorbing silver in circulation. Prior to this time, silver standards had been more common. In TTL, silver remains readily available from the mines of the stable UPSA (and later from the ENA and California), China is already open to trading in commodities other than silver ingots, and gold’s price has fluctuated due to earlier gold rushes than OTL, making it seem less reliable as a foundation.

[3] In OTL the Neapolitan Camorra was more notorious than the Sicilian Mafia in European eyes in the late nineteenth century; it took the appearance of the Mafia among Italian emigration to the USA (and it being highlighted in pop culture) for it to become the better-known of the two organisations.

[4] Saxon porcelain production at Meissen from 1708 was the wonder of Europe, being the first time a European had successfully emulated the process that made Chinese porcelain (an expensive import). The Sèvres factory was a later French rival, founded in Vincennes in 1740 and then moving to Sèvres in 1756. The Sant-Gobain company is one of the oldest companies in France, founded in 1665 and still going to this day in OTL; historically it mostly made mirrors and glass, but in TTL it has also become the owner of the Sèvres porcelain factory.

[5] Or in French, contrôleuse-générale.

[6] In 1688 the Ayutthai minister Phetracha launched a coup d’état and expelled French influence from Ayutthaya.

[7] Buenos Aires, named in honour of the Meridian Revolution when the Americans supported that, is on the site of OTL Dayton, Ohio.

[8] This is similar to OTL Keynesian economics – note that the description in the text here is brief, contextual, and does not go into detail.

“Yes, I know it was a bit of a forlor...I mean, a Finchley, Orpington, Rainham, Lewisham, Orpington, Rainham, Neasden, Hackney, Orpington, Pimlico...yes, you get the picture but what else could she... (long silence) She’s what? No, did I hear that right?”

–part of a transmission to or from the English Security Directorate base at Snowdrop House, Croydon, intercepted and decrypted by Thande Institute personnel

*

From: Motext Pages EX512C-G [retrieved 22/11/19].

Remarks: These pages are listed under “SAAX Economic Studies Revision: Syllabus A (Economic History Module 2)”.

Extraneous advertising has been left intact.

The Panic of 1917, also called the Great Contraction, is probably the single most famous (or infamous) economic catastrophe in the world. This is despite the fact that many economic historians have spent much ink in arguing that there are far worse examples. Going back to the bubbles of the eighteenth century, the South Sea and Mississippi Company collapses (in Britain and France respectively) ruined a bigger proportion of very wealthy people. The tulip crazes in what were then the Dutch Republic and Ottoman Empire were more colourful (no pun intended) and extreme in terms of the rapid inflation of the arbitary value of a commodity. But then the world was less connected in that period. Arguably the first really global economic hit was the Panic of 1883, nowadays far less well known, but actually more damaging than the 1917 Contraction by some metrics. The 1883 decline’s original trigger was the eruption of Krakatoa in the Batavian Republic, which caused global cooling and widespread crop failures in a manner that had already been witnessed in 1816 with the eruption of Tambora, albeit less intense.[1] Poor harvests in both the UPSA and ENA impacted on European economies, and a number of banks collapsed and smaller countries defaulted at that time due to excessive speculation in the boom time. Unemployment was rife. Governments fell in democratic or partially democratic nations, often leading to a revolving-door situation as their successors proved no less capable at solving the underlying problems. The King of Greece was briefly forced to flee the country before returning with Italian help—after the shaky young Italian state narrowly suppressed violent mobs itself.

The Panic of 1883 led to the multinational Congress of Antwerp in 1885, in which the European and Novamundine powers adopted a convertible Electrum Standard and pegged their currencies to a fixed rate of exchange based on the commodities of both gold and silver.[2] This also led to increased regulation of banking and the setting up of more national banks, which some countries had already possessed. The so-called ‘Antwerp System’ persisted for a quarter-century until the Pandoric War, and limped on despite the latter’s upheavals for another seventeen years. During this time, there were many warning signs (noted by a few far-sighted economic commentators) that problems were mounting up and would eventually explode when triggered. However, there was a strong alienistic mood among the leaders of the nations that they desired a return to normalcy and the prosperity of the Long Peace, and they associated the Antwerp System with those halcyon days. In this, as J. P. Prendergast noted in hindsight (writing in 1942) they ‘confused cause and effect in the manner of a South Seas tribesman making a fetish of an aerodrome to bring back a flying visitor; the Antwerp System had came about as a consequence of the conditions required for that prospertiy—it had not created them’.

Because of this, both elected and hereditary leaders remained stubborn to suggestions that the rigid 1885 system needed modification or renegotiation to respond to the modern world. The debts racked up by the Pandoric War continued to circulate and grow through interest, often ending up ten or twenty steps removed from those who had incurred them. The English farce “Not Likely, That’s a Tree!” (staged 1915, phanty-filmed 1920) includes a prophetic joke about the fictional Tartary-adjacent Sultanate of Groovefunkistan (playing on contemporary Flippant slang words) which is said to owe a war debt of sixty million roubles to itself following a series of confusing exchanges.

===

PRODUCT RECALL, JUBB SUPERSTORES: HEALTH RISK

If you have purchased any of the products listed on the page below between

October 4th and November 12th 2019, please follow the instructions given – HEM GOVERNMENT

Page IF100J

If you have purchased any of the products listed on the page below between

October 4th and November 12th 2019, please follow the instructions given – HEM GOVERNMENT

Page IF100J

===

But it would be a default on a very real debt that began the slide to the Contraction. In April 1917, driven in part by American frustration over delays in the construction of the Nicaragua Canal, the Kingdom of Guatemala missed a payment on the newly accelerated schedule of paying off the reparations she had been charged in 1899. There was promptly a public run on the Bank of San Salvador and the Guatemalan Army mutinied when King Felipe ordered it in to restore order in the capital. Mexican and American troops would move in to restore order and Felipe had regained his throne three months later, but by that point the global economic fuse had been lit by this first spark.

If it had not been Guatemala, it would likely have been Corea, which suffered a public uprising in late May and bank runs of its own. The elderly and out-of-touch King Geongjong had controversially imprisoned the reformist politician Lee Chang-jung, who had criticised Corean corporations in southern Yapon and India for making great profits whilst escaping taxation that might help the poor at home. The Corean public revolt alarmed both the Russians and Chinese, but it was the Chinese who came in to restore order, considerably reducing Russian influence in the peninsula. Some Corean nobles and other wealthy men briefly fled the capital of Hanseong [Seoul] in the face of public rioting, mostly going to the Corean colonies in Yapon. These found themselves shut out of returning, as one of the High State Counsellors cut a compromise deal with the released Lee to seize those men’s assets in return for leaving the rest alone.

These incidents, which could have been managed in isolation, caused global jitters and uncertainty which tipped all the trembling pots of stored-up war debt problems over the boil. “When America sneezes, Europe catches the flu” (today much modified with other examples) was coined by the Mount-Royal stockbroker Merton Bowers during the Panic. Countless loose ends had been created by the Societist Combine effectively writing off the debts of the old UPSA one way or the other, managed inconsistently since then. The Combine had refused to participate in the global economic system per se, carrying out more limited trade on an individual basis whilst working towards what Alfarus called ‘udarkismo’ (autarky, given an excessive Novalatina over-translation to sound new and exciting). This policy of self-sufficiency was not, as some pre-Iversonian conspiracy theorists would have it, proof that the Contraction was engineered by the Societists as part of their diabolical plan for world domination and one which they had prepared for. Rather, it was a move driven by the ideological desire to avoid ‘contamination’ by too much interaction with ‘the nationalistically blinded’. This is a position which arguably draws descent from Jean de Lisieux’s desire for buffer marches to ‘protect’ France from outside voices as he sought to change it to his nightmarish vision.

Given South America’s limitations in some resources, even with the addition of the East Indies and a large chunk of Africa, the ordinary Amigos and Amigas of the Combine were decidedly living in what Sanchez had called ‘equality of necessity’ in order to pursue this model of self-sufficiency for the ‘Liberated Zones’. However, this did mean that the Combine was more resilient in the face of the global crash as ‘it flung its tentacles destructively across the world like the final thrash of a dying octopus’ in the pithy words of Jacques Benoist. Russia also had the certain advantage of reliance on internal markets, though there was still widespread unemployment and the occasional food riot. In November 1917, Tsarevich Paul won plaudits from the people by imposing a one-off super tax on the RLPC’s profits for that year in order to subsidise new bread and potato rations. When he succeeded his father as Tsar two years later (though he had already been the real power at court for years) it would be as a man who enjoyed considerable popularity from his subjects—at the expense of deep suspicion from the Company men, a suspicion which would be deepened by his later actions.

France, on the face of it, should have been a country to suffer greatly from the Contraction. She was certainly not self-sufficient, and had built up a strong economic and military position that was highly reliant on a delicate web of connections across the world—based on the foundation of the Antwerp System. However, France had the advantage of a highly effective and dynamic government that enjoyed considerable public support. Robert Mercier had been in power as Prime Minister since 1905, winning three elections for his Diamantine Party amid the opposition Nationals struggling to find an effective counter. Philippe Soissons had succeeded Leclerc to lead the party into the 1910 election and had only lost further ground. Bertrand Cazeneuve had reversed that retreat, but Mercier continued to command a strong position in the Grand-Parlement.

This was despite the fact, as was an open secret to many in Paris (but not the wider kingdom), Mercier was a very ill man. His health had suffered considerably from a bout with the flu that had swept the world in the closing stages of the Pandoric War, theorised to be caused or exacerbated by the unprecedented global movement of soldiers. Though he had recovered from that, it had weakened his constitution and ever since, he could have months of strength and vigour followed by days or weeks of being bedbound for no apparent reason.

The fact that France nonetheless continued to be run consistently and well throughout his premiership was noted by those in the know (the wider people were successfully fooled by a variety of means into not suspecting Mercier’s condition). This was due to a number of reasons: Mercier’s mind did not suffer along with his body and modern communications meant that he could dictate orders from his bed via Lectel and quister; unlike the effective but Passeridic-managing Leclerc, he knew when to delegate; and, most importantly, there was his wife.

Heloise Rouvier had met and worked with Robert Mercier during the Pandoric War, in which she had assisted him in his role as Foreign Secretary. Rouvier had even taken over from Mercier in his first bout of illness, and had helped negotiate the postwar treaties with the Russians in particular. A strong-minded National Cytherean who idolised Leclerc’s mother Horatie Leclerc (nee Bonaparte), Rouvier was spoken of as rising higher than any female French politician ever had (unless one counted the rather unofficial role of Madame du Pompadour in the eighteenth century). This was all the more impressive considering only one in five Frenchwomen had the vote at this point.

However, Rouvier had been passed over for the role of Foreign Minister in favour of the less capable Soissons, in part thanks to her gender and (at that point false) rumours that she had fallen in love with Mercier. Some have portrayed her temporary retirement from politics and later marriage to Mercier as almost an act of spite, but this is to do her an injustice. Heloise Mercier did switch to the Diamantine Party and be elected as a parlementaire in her own right from that body, but she never compromised on her personal convictions and was always regarded as being on the doradist wing of the party.

During her husband’s tenure as Prime Minister, Heloise was frequently a go-between when he was in his bedbound state; many did not realise that (with his agreement) when he was too ill to make a decision, she would make it for him. Even when he was able to do so, he discussed the matters with her and took her advice. France was unofficially being run by a married couple, and sometimes by the wife alone. It was the sort of thing that had happened many times in the royal corridors of power, yet was a radical notion for democratically elected governance.

Historians disagree on just how much of France’s response to the Contraction can be attributed to Robert and how much to Heloise. Certainly, his periods of illness were scarcely closely documented for security reasons. Camille Rouillard, the Foreign Minister, also played a role; the actual financial role of Controller-General was held by Cedric Bouchez, a nonentity Diamantine grandee who had needed a top job in order to secure the support of his uncle’s old faction within the party. Regardless, the French government’s actions were swift and ruthless. France’s influence on other countries was rapidly deployed, with nations such as Spain and Autiaraux seeing public protests at taxes and tariffs imposed that would benefit French producers. There was also a mass sell-off of French state assets in India, a process that took inspiration from the Privatisation of Bengal but was achieved in a more gradual and measured way. The Maharaja of Mysore, Chamaraja Wodeyar XII, regarded this with alarm. Not unconnectedly, his people took note of the drawing-down of French military power in the region.

This policy was carried out with sufficient effectiveness that, though it burnt countless bridges and gave a number of countries and people new grudges against French, it allowed the government to manage the effects of the crisis without letting the hammer fall on the ordinary people of France (i.e. the electorate). Some historians highlight this as a key moment in the return of the values of the Democratic Experiment era, which had been partially suppressed by the so-called ‘Federalist Backlash’ in many countries. The mismanagement of the Great American War on all sides thanks to the erratic nature of democratic government had provided much ammunition for those who sought to limit its power. However, ‘La Mitigation du Mercier’ provided a (relatively) positive example of how democratic governments being beholden to their people could function. The spectre of revolution had never reared its head because the government had a vested interest in ensuring that the people be spared the worst of economic chaos, unlike the disaster of 1794.

===

“Draw an Automaton in one second!”

Pictoral Exercise—the board game for kids of all ages!

Page AD122H

Pictoral Exercise—the board game for kids of all ages!

Page AD122H

===

Of course, the effective French response was only possible because France could call upon resources and influences far beyond her metropole. The same was not true of many of her neighbours. Having stabilised her own finances, France was now able to exploit this from a position of relative strength, as did Russia and, to a lesser extent, China. At this point Italy was suffering from the reign of a group who were half a radical Mentian revolutionary organisation and half an organised crime syndicate; the Armata Rossa or ‘Red Army’. Probably descended in part from the old Neapolitan Camorra, the Armata Rossa had a significant role in government corruption, wanting its own men on the take in positions of power—and assassinating those who got in the way.[3] With an ineffective federal government in Rome and a compromised regional one in Naples, the economic crash hit Italy particularly hard and almost broke the country in half, just as the Panic of 1883 had. However, France helped stabilise the situation by contributing elite counter-insurgency troops fresh from the failed attempt to suppress the Dufresnie uprising. There were a number of high-profile arrests and shootings of Armata Rossa commanders in the south.

England, Germany, Belgium and Danubia also suffered from the crash. England was generally able to sort out her own affairs with only a little economic aid from France, but this did lead to the English Gendarmery outlasting its promised abolition date due to its usefulness in exerting the Government’s will (and, indeed it is around to this day). Germany was perhaps the most famous case of French intervention being key. The otherwise popular Hochrad government of Fritz Ziege saw its first real setback when inflation set in from the repeated devaluation of the Bundesmark in an attempt to lubricate the wheels of trade. It was a measure of desperation in 1918 when the Ziege government agreed to a bail-out package for the Dresdner Bundesbank from the Banque Nationale Royale. This came with a humiliating price; the French government seized the assets of the iconic Meissen porcelain factory near Dresden as insurance. In the meantime, production was managed by the Sant-Gobain company, which also owned France’s own Sevres porcelain factory.[4] This move weakened Ziege’s popularity, and he chose to retire in 1919, replaced as Federal Chancellor by fellow Hochrad Wolfgang Ruddel.

Crucially, France’s moves never targeted countries in such a way that their armed forces would be weakened. If this was, in some ways, a continuation of the actions the belligerents of the Pandoric War had described as being those of a ‘French Vulture’, they also fitted into a wider framework. Leclerc’s Marseilles Protocol had largely failed with the embarrassment of the war in South America, but the Merciers sought to rebuild its basic intensions with a more direct goal in mind. Russia was seen as the biggest threat to French hegemony and world peace, and France needed military allies—or, failing that, a ‘Bouclier’ or shield to put between Petrograd and Paris.

Not all countries accepted French help. Belgium, France’s historical enemy, resolutely rejected what the ageing King Maximilian IV described as ‘the outstretched hand of that foul harpy with poison on her nails’. (It is unclear whether he was referring to the female anthropomorphic personificaton of France, Gallica, or Heloise Mercier, whom he is known to have detested on a personal level). Belgium had been swinging from crisis to crisis for fifteen years, with the United Radicals taking power in the national States-General in 1902, but being frustrated by the more conservative States-Provincial blocking reforms on the King’s orders. The so-called ‘Belgian Party’ had returned to power in 1913 out of sheer public frustration with the gridlocked status quo, but had done so just in time to take the blame for the Panic of 1917. Fundamentally, up till now the Belgian people had been annoyed with their erratic and overly authoritarian royal governance, but had done so from a position of comfort and prosperity. The war with Germany might have been fought for the sake of a handful of pointless money-drain colonies that were promptly lost to the Societists anyway; it might be unwise to joke about this lest the Police Royale Secrète hear about it; but few lives had been lost in the conflict and bellies were still full. The Panic changed that, and now for the first time in decades, there were food riots in the streets of Brussels, Antwerp and Amsterdam.

It is ironic that, at a time when the old Dutch Republic could perhaps have been recreated off the bank of public anger, the exilic Dutch republics in exile had all fallen to Societist control only a handful of years before. Historians disagree, regardless, on how much of the old Dutch identity still existed as a coherent political force at this point; the Wittelsbach culture-war policy of persecuting the remaining francophone Walloons (and to a lesser extent the Westphalian Germans) had tended to weld together the former Flemings and Dutch. Religion remained a divide, but though the King was Catholic, pillarised tolerance of both faiths (and representation of both in the wealthy establishment) had been the norm since reforms of the 1860s.

===

Are you a home owner? Are you interested in a low-cost loan?

Contact Requin and Haai, page AD711K!

Contact Requin and Haai, page AD711K!

===

No, the biggest divide in Belgium was between rich and poor. When the States-General election of February 1918 produced a big win for the Belgian Party, the people knew the King had panicked and rigged it. A mass revolt ensued, the biggest European revolution since the Portuguese Revolution of almost seven decades earlier. PRS snitches were hanged from luftlights and their headquarters torched, town halls were seized, officials fled to loyalist areas such as Ghent and Luxemburg. Luik (formerly Liege), always a heartland of riot and rebellion in Belgium despite racial purging, became the rebel headquarters.

In the wake of this, French (and/or German) forces almost crossed the border if only to restore order. However, on April 4th 1918 the King confronted rebel forces at Antwerp. The same pleasant streets that, thirty-five years ago, had played host to the conference that had ended the Panic of 1893, were now stained with blood. Russian special forces, including elite Yapontsi ‘nindzhya’ troops, gunned down the Belgian rebels as both Belgian and Russian aerodromes bombed the barricades with death-luft from above. Europe watched in shock as Wittelsbach rule was ruthlessly restored, one town at a time, with much of the great historical Belgian heritage of art and architecture going up in flames in the process. Many refugees fled to France, invoking the Malraux Doctrine, or to Germany. By September 1918, Maximilian IV was firmly back on the throne—but with Tsarevich Paul’s hand on his shoulder. Maximilian proceeded to die only two years later, and his son Charles Theodore III was very much a Russian puppet. The European situation had changed radically.

Some historians criticise France for not intervening at this point. Besides the ongoing economic troubles, the primary reason for this is that Robert Mercier finally passed away in mid-April 1918, at the height of the crisis. King Charles XI (who had succeeded his father six years ago) wanted to appoint the grieving Heloise in his place, but once again prejudice in the Grand-Parlement made it unworkable. Instead, Rouillard became Prime Minister, but Heloise was kept on as the first female Controller-General[5] and continued the economic policies she and her husband had pursued. Rouillard is sometimes portrayed as an Areian villain in popular histories of Heloise’s life for this reason, but in fact the two liked and respected each other. Rouillard’s reputation is highest in his native Brittany, which enjoyed a resurgence in its language and culture thanks to his internal policies (which some have called proto-Diversitarian).

Given the ‘Bain-de-sang belge’ (Belgian Bloodbath) it is small surprise that people in this era regarded Russia rather than the Combine as a bigger threat to world peace. Russia also intervened in less destructive ways, with big loans to bail out both the restive Ottoman Empire and Persia, whose government had overspent without realising it thanks to low-level corruption. Russia attempted to make aid to California contingent on further concessions to bring the Adamantine Republic into a Russian orbit, but with only limited success (not least because California’s effective government also weathered the economic storm well). At this time, China took on many of the overseas Corean assets that no longer answered to its more cobrist government, expanding Chinese reach in India and southern Yapon. France’s primary intervention in the East came with help for Siam (a deal brokered by the Refugiados in the Philippines) which, again, was related to the ‘Mercier Doctrine’ of foreign policy which would set the stage for the Black Twenties. Mercier had believed that the lesson of the Pandoric War was that the only country that had the resources to stop Russia in a long war was China. His Eastern policy (continued by the new Foreign Secretary Vincent Pichereau) was intended to remove obstacles that would stand in the way of China focusing on Russia in such a war. Therefore, help to Siam was aimed at directing Siam away from a war of revanche for recovery of the lost parts of Tonkin, which would force China to fight on two fronts. The Siamese were suspicious, their history teaching them about unequal deals with France,[6] but for now it seemed the ploy might work.

Danubia was one place where something unexpected happened. Despite the relatively indirect way in which elections worked there, a decisive election result occurred in 1918 which saw the elevation of a plurality of Societist representatives to all four primary Volksrats. Precisely how this happened has been massively debated ever since. The Combine is known to have operated infiltrators across the world making moves from the shadows towards Alfarus’ ends (which does not necessarily mean backing local Societists). Because the elevation of the Vienna School was ultimately a bad thing for the Combine, the latter would later deny all involvement in the election result and censor the records, meaning finding the truth has become difficult. On the other had, it is certainly true that many Diversitarian narratives simply find it hard to accept that anyone would knowingly elect Societists, so perhaps that straightforward answer has been neglected.

Regardless, this led to a period of political paralysis in Danubia, but eventually the Grey Societists were accommodated in government. The people’s claimed motivation was that they wished the armed forces budget to be cut in order to free up funds to respond to the crisis, to help those who had lost their savings, etc. This was achieved to a limited extent, and Danubia was shifted towards a more ‘Bavaria-like’ neutral foreign policy, without embracing full Societism. This, indeed, was what Alfarus had feared when he had instituted his ‘udarkismo’; the purity of Sanchez had been corrupted by the everyday filth of compromise for the merely ‘immediate’ public good.

===

Have you been injured in a mobile accident that wasn’t your fault?

Insurers refusing to pay up? Traffic police useless?

Brocklesby Braithwaite, the People’s Solicitors, can help!

One quist is all it takes!

Page AD528L

Insurers refusing to pay up? Traffic police useless?

Brocklesby Braithwaite, the People’s Solicitors, can help!

One quist is all it takes!

Page AD528L

===

And what of the ENA, whose ‘sneeze’ had started all this? America had some of the same advantages of Russia or China, with vast internal markets that were less vulnerable to a global trade slowdown. However, President Tayloe’s government was already in decline by the time the crisis hit, and his response to it was far less competently handled than in countries like France or California. Indeed, Tayloe tried to blame everything on overspend by the late President Faulkner’s ‘Social American’ programmes (a commonly invoked scapegoat) and then attempted to slash them to curb the deficit, a move strongly opposed by the people and their representatives in the Continental Parliament. If anything, most economists now believe Faulkner’s somewhat isolationist policies and retreat from empire meant the ENA was now in a better place to weather the storm. He had also inadvertently helped Guinea and Bengal, which had more room for manoeuvre without being as closely tied into the Hanoverian trade system, and were able to gain more local influence with their neighbours as a consequence.

The 1918 American general election was a decisive victory for the Liberal Party, who almost won an outright majority and were able to govern effectively with the Mentians as coalition partner. Michael Briars, the now-ageing Liberal grandee who had lost out to Faulkner in 1900 and then been defeated for the leadership by the younger Michael C. Dawlish in 1908, had finally gained the leadership in 1909—only to then lose the general election to the incumbent Tayloe in 1914. Appropriately enough, perhaps, he was replaced by someone who traced his political identity from a similar story of losing out. David Fouracre III was the grandson of Sir David Fouracre, who had served in the Great American War and whose son had traded on his name in an attempt to win the Liberal leadership in 1875 on the death of Albert Braithwaite. David Jr. had been defeated by Michael Chamberlain, who had gone on to become one of the greatest Liberal Presidents. But in the next generation the Fouracre family of Buenos Aires, Erie Province, Pennsylvania finally had its shot at political glory.[7]

In the short term, Fouracre followed the advice of the economist Gordon Hareby, who argued that it was possible for a government to spend its way out of a depression through infrastructure spending to grow the economy.[8] (For more detail, see Economic Theories Module 1). This led Fouracre’s government to quickly finish the Nicaragua Canal, despite the Societists having built their own canal first, and embark on a number of other projects that would boost employment at the expense of further borrowing. Fouracre’s approach remains controversial to this day, but it is certainly true that many American roads, railways and public buildings would not exist without his ‘New America’ programme. Then and now, particular controversy attaches to the fact that many desperate poor workmen were often sent into dangerous situations for the sake of that infrastructure building, meaning Fouracre’s New America is generally seen as colder and more impersonal than Faulkner’s Social Americanism. Fouracre is generally portrayed as caring more about numbers than people.

In summary, then, the Panic of 1917 not only had a drastic impact on the lives of people around the world but severely weakened the old Electrum Standard, with many countries removing their currencies from the specie exchange system. It was joked at the time that the French livre was ‘backed by steel’, i.e. French military power meant that few would dare to call in their debts when the Merciers were trying to juggle too many balls of debt and keep them in the air at once. This was certainly also true of the Russian rouble. It was in this era that paper money, which had previously been circulated only temporarily and in times of war, became the norm.

Perhaps most importantly at all, however, the Panic also set in motion or accelerated many of the trends which set the scene for the Black Twenties. After countries such as Germany and Italy had tried to break out of the Marseilles Protocol following France’s embarrassment in South America, the response to the Panic meant they were now firmly once there again. French policy had changed, being somewhat less domineering and more seeking anti-Russian allies; but nonetheless, bridges had been burned...

[1] In OTL the 1883 Krakatoa eruption’s impact on crop harvests was relatively muted; in TTL, though the eruption itself is the same, the weather patterns are very different after over 150 years of divergence, and the effects are more severe (though still not on the level of the 1816 ‘Year Without a Summer’).

[2] The ‘Electrum Standard’ is so called because electrum is an alloy of gold and silver; we would just call it a bimetallic standard. Unlike OTL, there is no push for a single Gold Standard. This was driven in OTL by the economic heavyweight of Britain pushing for a gold-based recoinage following the debts of the Napoleonic Wars and a silver shortage caused by revolutions in South America and the China trade absorbing silver in circulation. Prior to this time, silver standards had been more common. In TTL, silver remains readily available from the mines of the stable UPSA (and later from the ENA and California), China is already open to trading in commodities other than silver ingots, and gold’s price has fluctuated due to earlier gold rushes than OTL, making it seem less reliable as a foundation.

[3] In OTL the Neapolitan Camorra was more notorious than the Sicilian Mafia in European eyes in the late nineteenth century; it took the appearance of the Mafia among Italian emigration to the USA (and it being highlighted in pop culture) for it to become the better-known of the two organisations.

[4] Saxon porcelain production at Meissen from 1708 was the wonder of Europe, being the first time a European had successfully emulated the process that made Chinese porcelain (an expensive import). The Sèvres factory was a later French rival, founded in Vincennes in 1740 and then moving to Sèvres in 1756. The Sant-Gobain company is one of the oldest companies in France, founded in 1665 and still going to this day in OTL; historically it mostly made mirrors and glass, but in TTL it has also become the owner of the Sèvres porcelain factory.

[5] Or in French, contrôleuse-générale.

[6] In 1688 the Ayutthai minister Phetracha launched a coup d’état and expelled French influence from Ayutthaya.

[7] Buenos Aires, named in honour of the Meridian Revolution when the Americans supported that, is on the site of OTL Dayton, Ohio.

[8] This is similar to OTL Keynesian economics – note that the description in the text here is brief, contextual, and does not go into detail.

Last edited:

Thande

Donor

Absolutely fine - the Kindle Unlimited setup actually makes up a big percentage of my royalties because it's calculated on number of pages and, spoiler, LTTW has a lot of pages! So that's certainly an option for anyone who isn't able to buy it outright.I will read LTTW 4 on Kindle Unlimited (sorry I can't afford to buy it, at least now.

Interesting how many cliches from OTL economic journalism make it into LTTW-verse...

“Draw an Automaton in one second!”

Pictoral Exercise—the board game for kids of all ages!

Page AD122H

Sounds like something between Etch-a-Sketch and a graphing calculator.

Share: