New part now - NB I realise that this is two Interludes close together, but the next main part is about China and I want to do some more research first.

Interlude #16: What Hath God Wrought?

“At the time of my birth, it was the norm for the majority of the population to be completely insulated from news and information from any other region save for those parts which their ruling class saw fit to disseminate. As I write these words, I see a world emerging where information is transmitted so freely across the world that soon it will be only by a deliberate act of wilful ignorance that a proletarian may remain unaware of such matters. I trust that not too many years after the time of my death, even such an act will be fruitless...”

– Pablo Sanchez, Pax Aeterna, 1845

*

From “12 Inventions that Changed the World” by Jennifer Hodgeson and Peter Willis (1990):

In the popular imagination, telegraphy in all its forms is, to use Iason Stylianides’ famous quote, ‘the Breath of Enlightenment’. The quote has a double meaning: the telegraph is both the final product of the Age of Enlightenment as it birthed the Age of Revolution, and also the wind of change that changed the world forever as knowledge spread wider and more freely than every before. Stylianides’ words may well have echoed in the mind of the sculptor Rodrigo Campos when he unveiled his work

Telegraphy Enlightening the Worldin Bordeaux Harbour in 1896, commemorating the centenary of Louis Chappe’s first semaphore tower. Campos’ work is a curious one that was controversial in its day, appearing at the bottom to be a classical semaphore tower design but morphing halfway up into the figure of a Greek goddess bearing forth a torch. Although vindicated by history, Campos attracted criticism in his day for choosing such symbolism, which seemed oddly inappropriate considering Chappe’s invention had competed with solar heliographs in its day. Perhaps, as some suggested, the exile Campos was simply taking the opportunity to wedge in a reference to his vanished country’s ‘Torch of Liberty’ symbolism and present a veiled challenge looking westwards from France at the ‘Liberated Zones’.

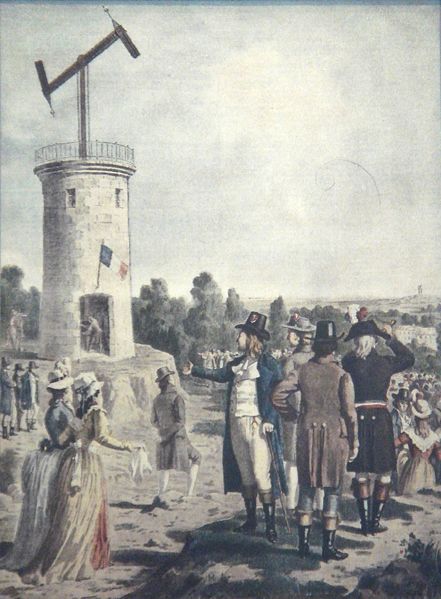

Campos is now already almost a century removed from we moderns, but let us travel back a further century to see the event that his statue sought to commemorate. In 1795, the inventor Louis Chappe had sought funding from the nascent National Legislative Assembly of the young French Latin Republic to develop his ideas for long-range communications. While ideas of technological progress in general were gaining fashionable status thanks to the efforts of the then still obscure Jean de Lisieux and the ‘Boulangerie’, it is uncertain whether Chappe would have gained support for his futuristic notion without the very old-fashioned one of nepotism: Chappe’s brother Philippe was a member of the NLA. Fortunately for the course of history, both of them managed to escape Robespierre’s purges and became indispensible to Lisieux, indeed to the point where even the restored Kingdom quietly allowed them to continue in their positions.[1] Chappe coined both the words semaphore and telegraph, from the Greek meaning respectively ‘signal bearer’ and ‘writing at a distance’.[2]The latter definition was key: a telegraph must not simply be some kind of meaningful signal at a distance, or the basic maritime signal flags that had been around for three centuries would qualify. It had to convey the same information as a written message, which in other words meant that it had to carry alphanumeric data.

Popular misconception, doubtless influenced by an overly simplified historiography of Chappe’s life told in popular science biographies, holds that Chappe developed his early angled-arm telegraph out of ignorance of the possibilities of shutterboxes, and only adopted those later when the idea occurred to him. In fact Chappe and his colleagues were quite brilliant men who had considered the possibility of a panel-based telegraph early on, but had dismissed the idea due to the panels being harder to discern from a distance than the arms.[3] Equally they experimented with placing lamps on the ends of the arms so the telegraph could be used at night, but found that observers could not as easily distinguish the lamps and abandoned this effort. The first version of the Chappe telegraph tower involved a T-shaped support with two angle-arms attached at joints to each end of the crosspiece of the T. Chappe and his colleagues intended the device to have at least four distinguishable signals (left up/right up, left up/right down, left down/right up and left down/right down) but found by experiment that a horizontal arm could also be distinguished by an observer from a reasonable distance, meaning a total of nine signals.

Chappe’s first line stretched from Paris to Lille[4] and provided a rapid communication line with the forces fighting at the front, proving invaluable for the government and even playing a part in Lisieux’s coup in 1799. The new leader of Republican France had always seen the potential of the semaphore technology, and Chappe was one of several engineers and inventors in the ‘Boulangerie’ to have additional funding and resources directed at them. Lisieux wanted more.

The chief problem with the first-generation semaphore system was speed. Messages were typically transmitted in their entirety from Tower A to Tower B and only when Tower B had received the whole message, transcribed it and checked it for errors, did it transmit it on to Tower C. This was still faster than existing methods of communication, with the possible exception of the unreliable and limited carrier pigeon, but Chappe could tell that it could be so much faster. The tower mechanisms, though gradually made more reliable, were too awkward to allow a continuous transmission of each letter from tower to tower.Though several innovative solutions were attempted, the problem was not resolved until 1801, when Valentin Haüy joined the company. Prior to the Revolution, Haüy had run what may be the world’s first school for the blind, for the first time treating them as fellow human beings worthy of employment rather than objects of mockery. His connections with the

ancien régime meant that he had been locked up by Robespierre, but fortunately had escaped execution, and had been released by Lisieux, a man whom—regardless of his other faults—would never throw away a life if it could be of service to France. Haüy had long since developed a system of embossed letters by which he taught the blind to read. However, this system was naturally limited, as Latin letters had not been designed to be read by touch and therefore needed to be very large to be legible by a blind reader. One of Haüy’s pupils, Jules Derrault, had developed a superior system, itself partially inspired by Chappe’s military signals, and Haüy brought the project to Chappe’s attention.[5] The Derrault alphabet converted letters and numbers into different combinations of six dots, which could easily be read by a trained blind reader if converted into a tactile form: a hole or pinprick for a dot and nothing for a gap. Not coincidentally, this could easily be ‘printed’ into a spool of paper by a modified programmable loom, and was compatible with the punch cards used to control such looms. Haüy had wanted a system that would let blind people integrate better into society, and so had been leery of using an exclusive system rather than something based on Latin letters—but the genius of Derrault was to realise that a great deal of the new technologies of the Revolution were based not on Latin letters, but on the binary punchcard system. By developing this blind alphabet and getting blind people used to using it, it would make blind people

more valuable to employers: they would have a skill that the sighted would find at least as hard to pick up, if not more.

Initially Derrault and Haüy had just hoped that they could store semaphore message data[6] on a punch card system and have it easily read by blind workers, but Chappe’s engineers were inspired by the Derrault alphabet to refine the transmission system as well. The final version of the Chappe semaphore tower, which served France ably through the dying days of the Republic and the restoration of the Kingdom, had a basic three-man operation team, supplemented with more personnel to allow working in shifts and sometimes to guard the tower or provide a messenger on foot or horseback to alert the other towers if this one malfunctioned. On both sides of the tower were six shutterboxes, each with a panel that could be tilted either horizontal to display a binary 0 or vertical to display a binary 1. At first all the panels were painted white, but later some were painted different colours to allow them to be more easily distinguished at a glance: the most common colour scheme and the one most people picture when thinking of those days had the first four panels painted white and the last two—which often functioned as ‘shift’ keys in the code—painted red. With six panels each displaying a binary signal, the overall signal was therefore hexameric, to use modern terminology, and this was the ultimate basis of the tendency towards hexameric data channels (or multiples of 6) in modern computer systems.[7]

When Tower A set its shutters to display the first letter in a message, then, the first man in Tower B would view the shutters (sometimes with the aid of a spyglass, in the case of particularly distant towers on flat ground) and, rather than try to interpret the letter himself, would just work a set of six on/off controls to duplicate the six signals on his end. Indeed, the company discouraged these workers, known as lookouts, from knowing the Derrault alphabet at all, reasoning that it would only distract them from their duty if they subconsciously tried to translate the letters as they went. In practice, of course, working alongside men whose job

was to translate the letters, together with the need for redundancy of expertise in case of emergency, meant this was a fruitless quest. The six controls typically took the form of levers for the hands, pedals for the feet and paddles for the elbows—these were said to be the trickiest of the three types—which were all connected to the main mechanisms of the tower. These had grown far more sophisticated after the turn of the nineteenth century, not just because of Lisieux’s extra funding but also because, following Lisieux’s abolition of Marat’s Swiss Republic, many Swiss engineers found work with Chappe’s company. Purely by coincidence, of course, it was a great deal easier to obtain a certificate of genuine Latin ancestry if one happened to have expertise that would be useful to the company and, by extension, to L’Administrateur.

After the lookout worked his machinery, a mechanism derived from a programmable loom would go into action. A paper tape, constantly moved along by a small steam engine or manpower, was passed over an arrangement of six needles. The appropriate number and position of the needles would be raised by the mechanism as the lookout worked the controls, duplicating the transmitted letter that the lookout had observed as a punched-out pattern on the paper tape. The tape would then spool onwards underneath the ready fingers of one of Haüy’s blind workers, who would immediately recognise the punched code from long experience and call out the letter or number to the third man, who would work his own controls to set the shutterboxes on the other side of Tower B, ready for Tower C to see the message. Chappe attempted several times to create a system where the lookout’s controls would directly work the shutterboxes on the other side to eliminate the third man and retain the blind worker only as a proofreader and checker, but this was never satisfactorily accomplished.

Though this system may sound complicated, the specialism of each man in their specific role—as had been observed by Richard Carlton[8]—meant that the process became very rapid compared to the older towers, and messages could now be transmitted far faster. Chappe later added double sets of shutterboxes and workers (or sometimes just built a second tower alongside the first) to allow messages to transmit both up and downstream at the same time. The Chappe network, centred on Paris, was the envy of the world and was regularly updated for years later, though in the end this also meant that France was late to adopt the system that would become its replacement.

The word ‘Optel’ of course was not coined until the mid-nineteenth century; why would anyone bother specifying that Chappe’s system was ‘optical telegraphy’ unless there was an alternative to measure it against? This would not be the case until that alternative, Lectel, was created around the middle of the century. Prior to that, the only alternative had been heliography, using reflected sunlight and a focusing mirror to transmit flashes across a long distance. Heliography had some advantages over Optel, principally being more portable and versatile, useful in battlefield situations. However, for general use this was outweighed by the fact that heliography was a single binary set of flashes, in other words a unimeric data system—and of course that it was dependent on the sun being out. Heliography’s general use was considerably improved when the Dutchman Willem Bicker published his code system in 1813. Bicker had the idea of expanding heliography from a binary to a ternary system by adding a third category of signal: rather than just 0 and 1, he had 0, 1 and 2, with 1 being a short flash and 2 being a longer flash.[9] This meant that it was far easier to transmit alphanumeric data with relatively short code segments for each character. Furthermore, the principle could be applied to other systems as well, such as lamps by night (particularly useful on ships) and, in the most farcical example, Optel that used a single large shutterbox or arm instead of several small ones. Such a system was built across the Dutch Republic and Kingdom of Flanders in the 1810s, perhaps in pride at Bicker’s nationality, with the claim that it would be visible from a longer distance than Chappe’s hexameric shutterboxes and the smaller number of towers would make up for the less efficient data transfer. In the end this proved to be nonsense. However, Chappe’s company—led by his son after his death in 1826, just before his invention would prove to play a key role in the Popular Wars—did quietly adopt the Bicker code for a night transmission system, which just used the existing Optel towers as the housing for a single large lamp. Though slower than the shutterboxes, it was better than nothing in darkness, when attempts to use six lights to replicate the Derrault system by night had proved to result in too many transmission errors. Bicker code was also extensively used by rebels during the Popular Wars, especially in Britain and Germany.

But in the popular imagination it will always be the Optel shutterbox that symbolises the technological explosion of the early nineteenth century, and even within that time it was an object of pride for France. Other countries adopted the system, Saxony and Swabia probably most successfully, their inventors even improving on elements of the mechanisms. Russia was slightly slower to adopt it but soon saw the advantages, while Francis of Austria naturally held back that nation in that regard. The greater distances in the Americas meant that though Optel did boom in those countries to link groups of nearby cities, it did not serve to connect the frontiers to the capital as it did in smaller European countries. Thus it is no surprise that adoption of Lectel would be a much simpler process in the Americas, hardly a major front in the so-called ‘Telegraph Wars’ of the mid-nineteenth century, as Lectel did not have an already established system to compete with.

Chappe’s company did not keep a monopoly in France, and many other French telegraphy networks sprang up over the years, but many of them struggled to find something new and unique to bring to the table. Many had the idea that adding more shutterboxes would be better, meaning more data could be transmitted with each shot, but missed the point that six was the maximum that an operator could easily encode with one movement. The French idiom ‘as useless as an eight-panel semaphore’ remains in common use today, over a century later, illustrating how big the failure of such devices was felt in popular culture. One engineer proved more ambitious, more audacious, than the rest, and though his creation would have been useless as a common means of transmission, it captured the hearts of Parisians forever. Isambard Brunel[10] unveiled ‘Le Colosse’, a gigantic shutterbox built into the side of a disused Utilitarian building on the Ile-de-France, pointedly within view of L’Aiguille—the great tower of Lisieux, built on the site of demolished Notre Dame, which was still the central hub of the Chappe semaphore network. Brunel’s shutterbox, reflecting the Titanic size of many of his projects, consisted of a square of

eighteen by eighteen panels, for a total of 324. The device was operated by an insanely complex series of punchcard mechanisms built into the old building, and it took as much as half an hour to set all the panels correctly. Useless for transmitting data—at least the traditional way. Brunel’s genius was to realise that the building could be viewed from a long distance, and over that distance, he had enough iotas[11] to create a pattern that would be blurred by the eye into a recognisable image. The 324-iota pattern could be broken down into 54 blocks of six—which could be transmitted by a Chappe semaphore as a code from anywhere in France and then slotted into place to produce the image. In other words, anyone in France, for a fee, could have an image displayed where all of Paris could see it.

Though—like most of Brunel’s ambitious projects—Le Colosse was a financial flop, it captured the imagination. French newspapers (and soon those in other countries) were exploiting the Brunel technique to transmit the codes for basic images across an entire country. Often they were too fractured to make out much detail, but buyers were mad for the new fad. Ironically, Le Colosse became so iconic that it remains in Paris to this day, restored and used to display commemorative images on national days, when Optel itself has long since fallen to the ravages of time...but the story of Lectel is for another chapter.

[1] A happier fate than his OTL counterpart, Claude Chappe, who committed suicide by throwing himself down a well in 1805 due to a combination of depression and having been accused of plagiarism from military semaphore systems.

[2] Which was also the case in OTL for Claude Chappe.

[3] Also true in OTL. Panel-based telegraphs were used by the British military during the Napoleonic Wars, but were dismantled after the war and never really caught on, with the angled-arm type (refined by the Prussian military) being the norm until the invention of electric telegraphy.

[4] Also in OTL.

[5] In OTL, Haüy’s school was home to one Louis Braille, who was also inspired by military signals to create an alphabet similar to the one being discussed here.

[6] The use of the word data for information, being the plural of the Latin ‘datum’, is much older than computing and well predates the POD.

[7] Hexameric = 6-bit, to use OTL terminology.

[8] Richard Carlton was a Carolinian writer and economist who, in the 1810s, republished Adam Smith’s works with additional commentary and work by himself. Smith wrote much the same works as OTL, but because he was a Scot at a time of suspicion of the Scots and suppression of political activity there by the British government, his works were not widely recognised in his lifetime and often misattributed to Carlton. In this case the writers are referring to Smith’s observation that production in a factory becomes greatly magnified if different workers each specialise in getting very skilled in a different specific task that forms part of the process rather than being jacks of all trades—which is known as ‘division of labour’.

[9] This is obviously similar to OTL Morse code’s dots and dashes, but in fact the idea is older than Morse code in OTL, and the military code system that inspired Braille in OTL used dots and dashes.

[10] Not Isambard

Kingdom Brunel, obviously, but his father (or ATL counterpart of same), Marc Isambard Brunel, who preferred in his lifetime to be known by his middle name. In OTL he fled France soon after the Revolution for saying unwise things about Robespierre, but in TTL managed to stick around in Royal France during the Jacobin Wars and continued after the Restoration.

[11] In OTL we would say ‘pixels’. For purpose of comparison, Brunel’s Colosse has 324 pixels, while the small images that can be found to the left of the address bar in web browsers are made up of 256 pixels.