Clement Attlee

Labour

(1945-1953)

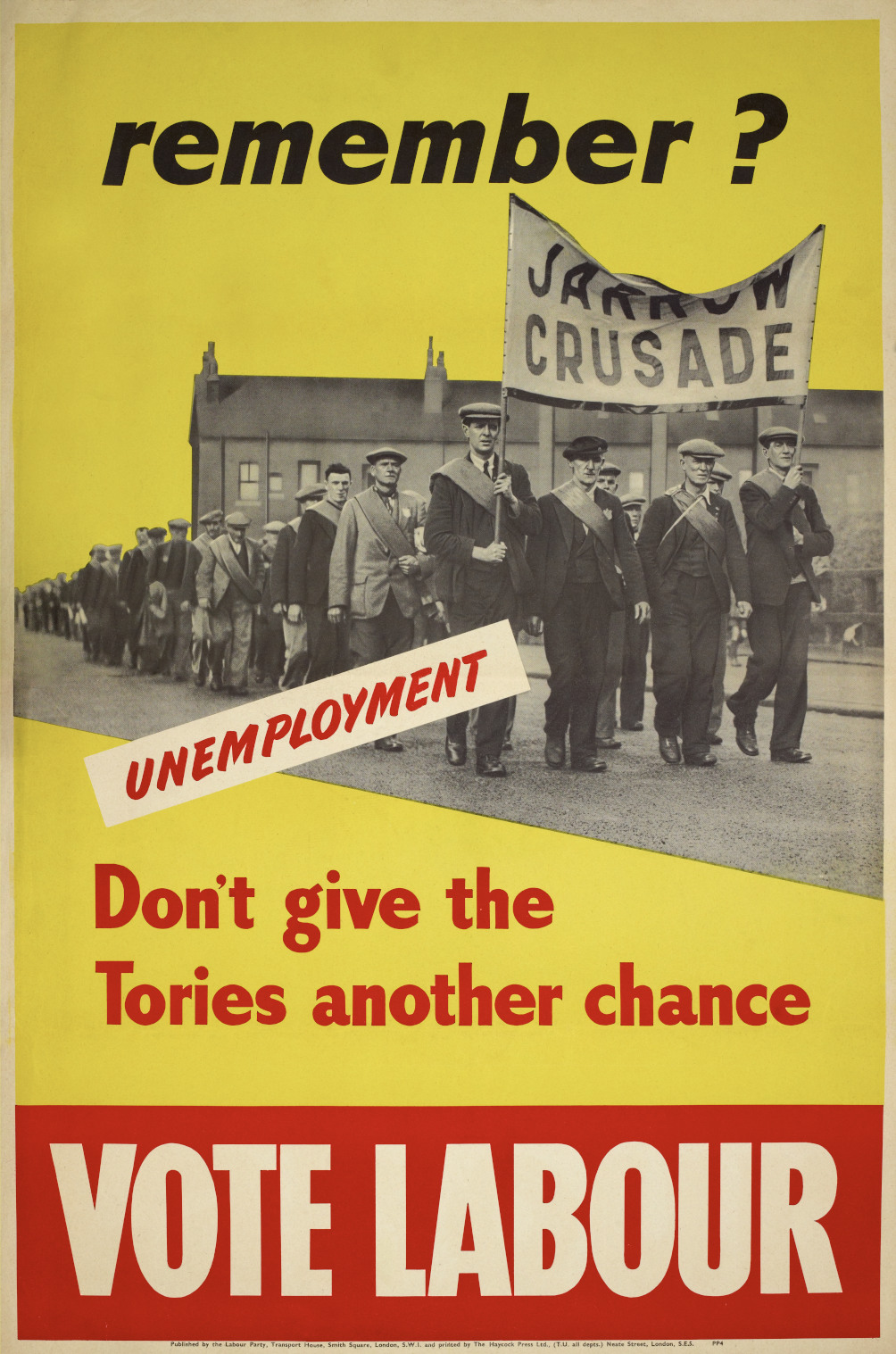

With the War in Europe over the wartime coalition government dissolved and Britain headed to the polls for the first time in nearly ten years. Winston Churchill was regarded by many as ‘the man who won the war’, and was by far the most popular politician in the country. However memories of the aftermath of the Great War remained strong, and how Lloyd George had proved successful in leading the nation to victory but had failed to create the promised ‘land fit for heroes’. Instead it was Labour led by Clement Attlee who captured the public mood promising economic planning, public ownership and a greatly expanded welfare state. Labour achieved a landslide victory in 1945, winning an overall majority of 144 seats.

The new government quickly set about implementing its ambitious manifesto. The Coal industry, railways, electricity board, gas board and Bank of England were nationalised. A system of National Insurance was created, encompassing state pensions, sickness benefit, unemployment benefit, maternity benefit and funeral benefit. New Towns were created, and nearly 1 million new homes were built between 1945 and 1950. National Parks were created, and the Town planning system was overhauled. The crown jewel in Labour’s domestic policy was the creation of the National Health Service, providing universal health care free at the point of use. In foreign affairs Attlee and his forceful Foreign Secretary Ernest Bevin aligned Britain firmly with the United States, and helped to form NATO to defend Western Europe against the Soviet Union. Britain withdrew from India, Burma, Palestine and Ceylon.

Labour’s victory in the June 1950 election is now considered a foregone conclusion, but Labour was not always likely to win a second term. Opinion polls through 1948 and 1949 were bleak, indicating a significant swing against Labour and a Tory lead varying between 3 and 10 points. The boundary changes implemented under the Representation of the People Act undoubtedly harmed Labour, as many underpopulated inner city seats were abolished, and many more seats altered. It estimated the boundary changes alone cost Labour around 40 seats. The timing of the election itself was a point of controversy. Whilst Attlee, Morrison and Gaitskell favoured a May or June poll, the Chancellor Stafford Cripps was later to write that he was strongly opposed to calling an election after the April budget, believing it would inevitably make popular budget measures seem like bribing the electorate. Cripps’ health, often fragile, took a turn for the worse in December 1949, and he was not involved in serious election planning.

Labour entered the June election campaign with several advantages. Firstly the decision of the Liberal Party to field 503 candidates – the most since 1929 – undoubtedly harmed the Tories, as a majority of potential Liberal voters were of an anti-socialist persuasion. Secondly petrol rationing came to an end in May 1950, a popular move which undoubtedly swayed a few swing voters towards returning the government. A summer election was also always likely to have a higher turnout than one held in the winter months, and a higher turnout was always felt to help Labour. Finally a June election gave the Labour party machinery time to prepare for a campaign.

Labour fought a strong campaign, with Herbert Morrison rallying the faithful, arguing that a Labour victory in 1950 was even more imperative than that of 1945. Attlee was famously driven around Britain by his wife Violet in their family car, making over 30 public speeches. In the end 1950 election saw a significant swing against the government, but Attlee was returned as Prime Minister with an overall majority of 43.

Not long after the 1950 election two of the government’s most dominant figures left the stage. In August Stafford Cripps, who’d long been in poor health, finally retired as Chancellor. Cripps’ successor was his deputy, the Economic Affairs Minister Hugh Gaitskell, who at 44 years old was the youngest Chancellor since Austen Chamberlain half a century earlier. Meanwhile the robust figure of Ernest Bevin stepped down from the Foreign Office the following April, he was replaced by Colonial Secretary Jim Griffiths.

Days after the election North Korea invaded South Korea. The Korean War brought the real risk of the Cold War going Hot, and Britain was forced into rearming in preparation. The cost of rearmarment necessitated cuts to some of Labour's domestic programmes, with Hugh Gaitskell announcing the introduction of fees for dentures and spectacles on the National Health Service. This, combined with his annoyance at not receiving either the Treasury or the Foreign Secretaryship led Aneurin Bevan, along with Harold Wilson and John Freeman to resign from the cabinet. Bevan’s decision to resign in effect ended any realistic hope for him to succeed Attlee as party leader. Of the three only Wilson was to later return to cabinet.

In contrast to the hurried legislating of the 1945 parliament, the parliament of 1950 was to be much quieter. Iron and Steel nationalisation, legislated for in 1949, took effect in 1951. The nationalisation of the cement industry with the creation of the Cement Board and the sugar beet industry through the creation of the British Sugar Corporation - both in 1952 - marked the last of the great post war wave of public ownership.

The defeat of 1950 caused great consternation within Conservative ranks. If the parliament lasted for a full term the Tories would face their longest spell in opposition since the 18th Century, and even when the Liberal’s had been returned in the elections of 1910 it had been as a minority, whereas the re-elected Labour government had a stable majority of 43. Churchill himself sank into a deep depression following the election, he had been a largely absent opposition leader in the 1945-50 parliament, and had spent much of his time abroad playing the role of international statesman. A significant number of backbenchers blamed Churchill’s lacklustre leadership for the defeat. In November 1950 Churchill bowed to the inevitable and retired as leader, handing over to his long serving deputy Anthony Eden.

After the economically difficult years of 1950-1952, where the government faced a balance of payments crisis and war in Korea, 1953 was to be a year of recovery. The coronation of Elizabeth II in June followed by armistice in Korea in July convinced Attlee that, like Stanley Baldwin, it was better to bow out whilst on top. Attlee swiftly resigned that September.