Let Us Win Through Together

a British Politics Wikibox tl

by gaitskellitebevanite

Chapter 1

a British Politics Wikibox tl

by gaitskellitebevanite

Chapter 1

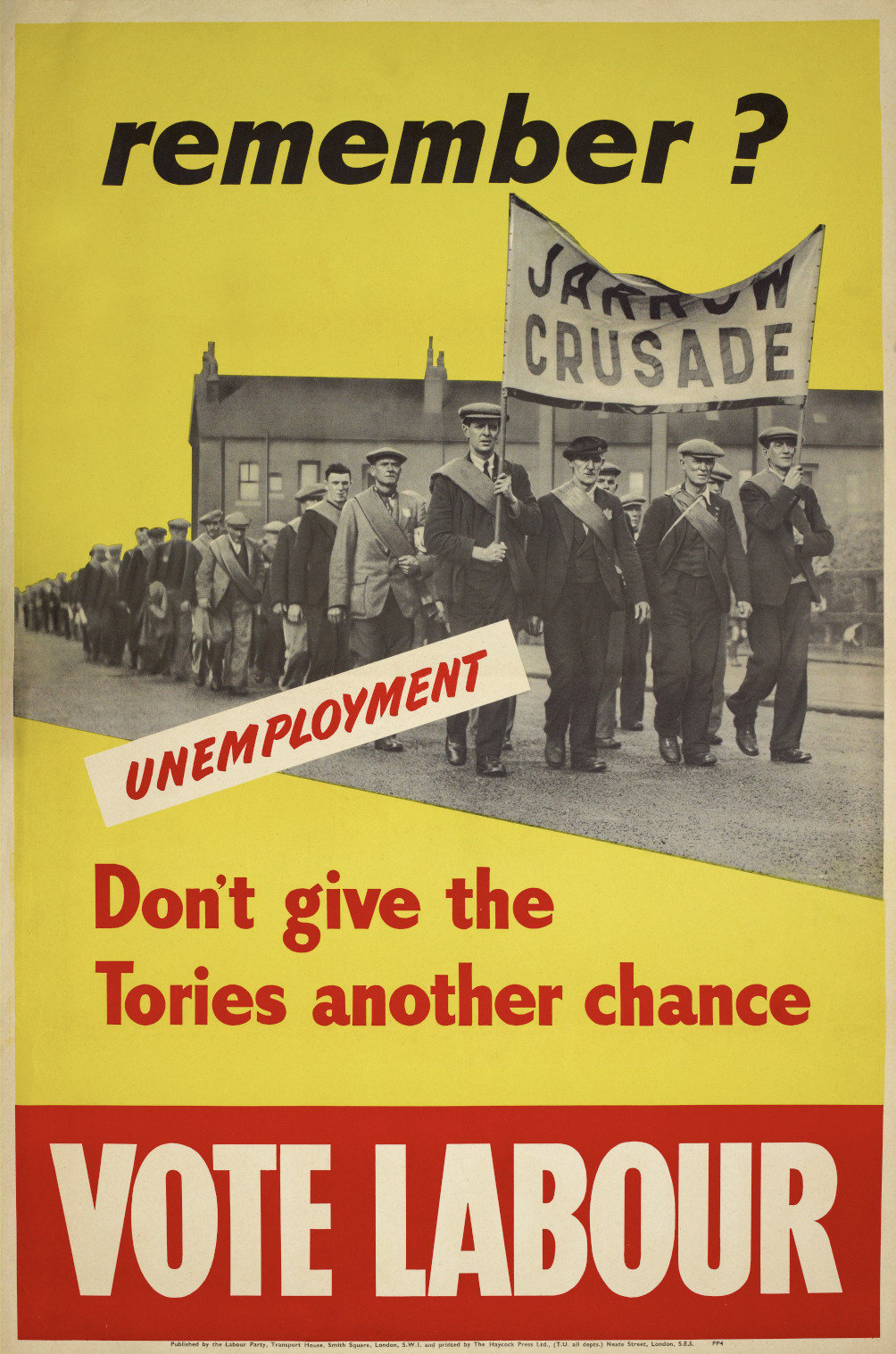

Labour’s victory in the June 1950 election is now considered a foregone conclusion, but Labour was not always likely to win a second term. Opinion polls through 1948 and 1949 were bleak, indicating a significant swing against Labour and a Tory lead varying between 3 and 10 points. The boundary changes implemented under the Representation of the People Act undoubtedly harmed Labour, as many underpopulated inner city seats were abolished, and many more seats altered. It estimated the boundary changes alone cost Labour around 40 seats.

The timing of the election itself was a point of controversy. Whilst Attlee, Morrison and Gaitskell favoured a May or June poll, the Chancellor Stafford Cripps was later to write that he was strongly opposed to calling an election after the April budget, believing it would inevitably make popular budget measures seem like bribing the electorate. Cripps’ health, often fragile, took a turn for the worse in December 1949, and he was not involved in serious election planning.

Labour entered the June election campaign with several advantages. Firstly the decision of the Liberal Party to field 503 candidates – the most since 1929 – undoubtedly harmed the Tories, as a majority of potential Liberal voters were of an anti-socialist persuasion. Secondly petrol rationing came to an end in May 1950, a popular move which undoubtedly swayed a few swing voters towards returning the government. A summer election was also always likely to have a higher turnout than one held in the winter months, and a higher turnout was always felt to help Labour. Finally a June election gave the Labour party machinery time to prepare for a campaign.

The 1950 election saw a significant swing against the government, but Attlee was returned as Prime Minister with an overall majority of 43.

Last edited: