Lands of Red and Gold #112: Stuck In The Middle With You

The main Hunter sequence is still having some maps and other graphics finalised, which will make for a much clearer tale once completed. In the meantime, this chapter gives some insight into what's been happening in the Atjuntja realm.

* * *

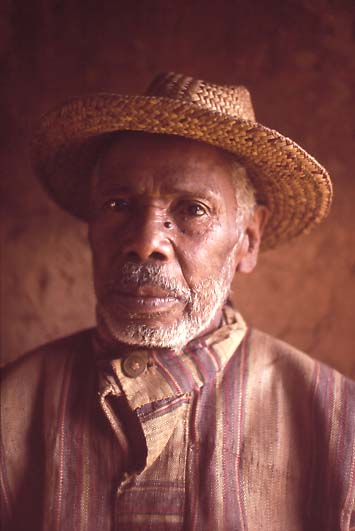

“I do not wish to free the people. I wish the people to free themselves.”

- Tjewarra (“strong heart”), Atjuntja activist

* * *

Sandstone Day, Cycle of Honey, 475th Year of Harmony (6.3.475) / 19 April 1714

Witte Stad [Albany, WA], Teegal [Dutch protectorate over Atjuntja realm]

The waters of the outer harbour were placid as the Eternal Fire passed south of the two islands that marked the harbour limits [1]. A fine, pleasant day for so early in the year.

May it be a sign of calm and pleasant trading when the ship docks. Balanada, newly-raised captain of the Liwang bloodline, would welcome such a time. Witte Stad was always an unpredictable port; sometimes placid, sometimes gravely troubled. This was his sixth visit to the capital of Teegal, though the first as captain. Twice the city had been unmarred, twice there had been agitation, and knives at night, which made proper trading most difficult. Once there had been a disturbance amongst the slaves a few weeks before his ship arrived, and the aristocrats had been busy arguing with the Nedlandj to spare those of their sons who were slaves. That time, trade had been all but impossible.

Now, Balanada was captain, and now, he hoped, there would be good fortune in his commerce. Two times calm, three times unrest, so with luck the next time will be calm.

A short burst of stronger wind sent ripples through the sails and a stronger flap to the flag which flew at the masthead. A flap of purple. A reminder, as always, of his grandfather’s favourite complaint. His grandfather had never stopped talking about how in his own time at sea, ships of the Liwang had dyed their entire sails purple to announce that their bloodline owned the ship, rather than the “small flapping flags” they now carried.

Balanada could not comprehend such a fantastic waste of money. The Liwang had been the wealthiest bloodline in former times, or so his grandfather had claimed, with a wealth built on dyes, and most especially sea purple. Nowadays, he could not afford to dye his sails purple. Even if he could, he would not have squandered wealth in such a fashion. He found it wasteful enough to need to use sea purple even on a flag [2].

The breeze returned to its former slight push, and the Eternal Fire resumed its slower, steady course toward the inner harbour and the docks of Witte Stad. Balanada kept his calm vigil; his crew were well-trained and he did not need to give them any orders.

May there be wealth worth the finding here. A hope which might be dashed, as it had for many other trading-captains over the years. His grandfather had often bemoaned the decline in the Island’s fortune; by the time his life drew near its end, he spoke of little else.

Once, there had been twenty-one bloodlines on the Island, his grandfather had said. Six bloodlines had left to found the Nuttana, and brought many men of other bloodlines with them. Two bloodlines had fled to Aotearoa, and one to Tjibarr. Seven had been consumed by plagues, famine, feud and vendetta, with their members gone entirely or their few pitiful survivors adopted into other bloodlines.

Balanada could not even name those vanished bloodlines. Five bloodlines remained on the Island now, and as far as he was concerned those were all that mattered. So many Nangu had left the Island over the long time of troubles. Even now, a trickle of Nangu left every year, and he had received several invitations to join them.

Balanada spurned all calls to move from the Island. Undeniably, the call of lucre was strong. The Nuttana thrived where those of the Island could hope only to survive. Closer to home, the Tjibarri in Dogport [Port Augusta] and Jugara [Victor Harbor] were always offering to pay well for experienced sailing captains.

Despite the many invitations, Balanada had never been tempted to move. The Island was his land, the land of his blood, the land of his forefathers. He would not give it up.

So he remained with those bloodlines who still lived on the Island. His grandfather and father had always been conscious of the glory which had once been, and spoke much of it. Balanada preferred to look forward, watching for what wealth might come once again. It might be here in Witte Stad, or so he hoped.

The Eternal Fire completed the remaining part of the journey peacefully, and tied up at an empty dock at Witte Stad. Balanada barely glanced at the city as they approached. His father and grandfather had both talked at length about the splendour of Witte Stad, but the Nedlandj had ruined most of the city a couple of decades before. What little had been rebuilt had been designed for function, not grandeur.

A group of a half-dozen bearded Atjuntja waited at the dockside, together with one Nedlandj. He saw with some amusement that four of the Atjuntja wore Raw-Men style waistcoat and breeches, with the other two being armoured soldiers. The Nedlandj wore the same style of clothes, but with a pink-powdered wig. The Nedlandj also stood to the back, as if he were the least important, when everyone knew that the Nedlandj ruled Teegal in truth.

The Atjuntja asked a barrage of questions, which he answered as best he could. Yes, he had been to the White City – as they still called it – before. Yes, he would honour the laws of the King of Kings. No, he had not committed any former displeasures. While on shore, he would reside in the Islanders’ House, unless a local dignitary gave him hospitality. No, he did not have any such contacts now, he was speaking hypothetically. No, he did not have a departure date decided yet. He would leave as soon as his trading was completed. Perhaps six days, perhaps twelve. Certainly no more than twenty-four.

The questions continued, and Balanda kept answering in the same polite, responsive manner. Atjuntja officials could refuse docking permission for any reason, and sometimes did so on a whim. Thankfully none of these officials had sought a bribe yet, since that could cut significantly into his potential profits.

The Nedlandj watched the questioning, evidently knowing enough of the Ajtuntja tongue to follow. A more accomplished fellow than most Raw Men, who often spoke only their own languages. Balanada could have responded equally fluently in the Atjuntja tongue, the Nedlandj speech, or the words of the Island.

After the Atjuntja officials seemed satisfied, the Nedlandj stepped forward and said, “What cargo do you bring to trade?”

“Whale oil, whalebone, smoked whale meat, gum cider, dyes of orange and sea purple and Tjibarri blue.”

“Any kunduri?”

“Not for trade. A few of my men carry some for their own use, I believe.” The Eternal Fire carried a small cargo of fine Tjibarri kunduri-snuff, but he would only bring it ashore if he could find somewhere private to sell it.

The Nedlandj grunted. His Company set the true rules for what could be bought and sold in Teegal. They tolerated the Nangu coming to trade, but required that key goods must be sold directly to the Nedlandj, not to the Atjuntja. Only goods which the Nedlandj cared little about could be bought from or sold to the people of the Middle Country.

According to the rules which the Nedlandj set, gold, spices and what little sandalwood was still grown here had to be sold to their Company, and no-one else. Some dyes were likewise restricted, particularly indigo, though some could be freely traded.

Restrictions applied also to what the Nangu could sell here. Balanada had only admitted to trading in products which were freely permitted. The Cider Isle still produced a little gum cider, despite all the troubles there, and the Atjuntja still enjoyed drinking it. The Nedlandj had never cared for gum cider, and so permitted that. Likewise, the Nedlandj saw little worth in orange and purple dyes. Tjibarri blue was new enough that the Nedlandj did not yet appreciate its value.

For some other goods, the Nedlandj set different rules. Such as how the Nedlandj insisted that any kunduri or sandalwood be sold only to them, not to any Atjuntja.

Sandalwood had become very rare in Teegal, due to the Nedlandj over-harvesting it. So rare, in fact, that the Tjibarri had taken up sandalwood cultivation in the Five Rivers, and produced some surplus which they sold elsewhere. He found some quiet amusement in the prospect of selling sandalwood to the Atjuntja; his grandfather and father had always used the saying “selling sandalwood to the Atjuntja” to mean accomplishing something impossible.

Despite that amusement, Balanada had not brought any sandalwood on this visit. Risks came with carrying it, since any ship which carried sandalwood would be watched closely in case of illicit trade. Besides, selling sandalwood directly to the Nedlandj was not worthy of a trade voyage; the Tjibarri charged too much and the Nedlandj paid too little.

Kunduri was another matter. Deprived of the drug, the Atjuntja had been forced back onto the accursed locally-grown tobacco [3]. In turn, that meant that any Nangu who were brave enough and found the right contacts could sell kunduri to the Atjuntja for good prices, though still cheaper than the prices which the Nedlandj charged for their own kunduri grown in distant Adjreeka. Only aristocrats, and not all of them, could pay the prices which the Nedlandj charged.

“See that it is not sold here,” the Nedlandj said. “Any news worth the telling from the east?”

Nothing which I want to give away for free. Oh, except one thing. “Some barbarian warlord is said to be causing trouble for the Inglidj in Daluming.”

The Nedlandj grunted. “That is not worth the telling.” He turned away, which satisfied Balanada perfectly. He wanted to have little to do with this Nedlandj, or indeed any Nedlandj.

Taking that as a cue, one of the Atjuntja officials told him that he was permitted to visit Witte Stad, though he would be required to give an account of all trade before he departed. Balanada gave that assurance, naturally, despite having no intention of honouring it.

In truth, selling goods to the Atjuntja was the easier part of trade here. Whale oil, gum cider, the right kind of dyes, and circumspect kunduri, sandalwood and other goods – there was much that the Atjuntja wanted to acquire. The greater challenge was finding something they had that was worth buying in exchange.

Bloodroot was something which the Nedlandj cared little for, so it could be bought. That had some profitable uses back in the east, for those who craved its hot, slow-burning taste, or the varieties used as a dye [4]. But bloodroot alone was not enough to be worth visiting Teegal. Occasionally there were Nedlandj goods that were worth buying from the Atjuntja and reselling further east, such as foreign spices or steel goods or fine cotton textiles.

Inevitably, though, he would not find enough here of value. Officially speaking, that is. When he departed here, the official trade records would show that he had sold much and bought little.

As he had learned over several visits, the truly valuable thing to buy here was gold. Gold was strictly forbidden for sale. Yet no matter how much the Nedlandj tried to control gold production in Teegal, some of it leaked out. Inevitable, when they kept slaves in such a manner. Slavery should be regulated, of course, but by all reports the Nedlandj thought of slaves as people who would die soon, so not worth bothering to treat well.

No surprise, then, that slaves smuggled gold out of the mines where they could. In turn, some of that gold would flow through to Nangu visitors, if they were astute enough in commerce. Balanada certainly planned to obtain as much gold as he could, and bring it home. A captain who could not hide some gold aboard his ship was not worthy of command.

* * *

Black Cockatoo Day, Cycle of Honey, 475th Year of Harmony (8.3.475) / 21 April 1714

Witte Stad, Teegal

A dozen or so men walked ahead, each shackled to the one in front. Men whose skin was slightly lighter in hue than that of the average Atjuntja, and whose curled hair would have marked them as foreign slaves even without the chains.

Balanada had to stop his lips from curling in distaste. More slaves for the Nedlandj to work to death. Or perhaps these were slaves destined for the household of some noble, many of whom had learnt the same wasteful attitudes from the Raw Men. Slavery had its place, but slaves were still men, not beasts. Something which the Atjuntja and especially the Nedlandj often forgot.

Balanada’s guide, a puzzlingly beardless Atjuntja who refused to give his own name, paid no heed to the slaves, walking around them quickly. Balanada matched his pace, and moved on, seeking to put the slaves out of his mind. Commerce was his objective here, not teaching the Atjuntja how to live properly.

Soon enough, he was ushered into the grounds of an Atjuntja house. A large mansion, with equally impressive gardens to match. Not everything had been destroyed in the Nedlandj ruination.

The first chamber inside the house had walls covered with finely-woven tapestries. They showed a series of scenes of the sun above the water, of men fighting with burning swords, of birds taking flight, and a thundercloud against blue-white sky. Strange. He had never seen the like before, but they fit with his father’s descriptions of the fine weavings which used to be produced in Durigal, before the Great Dying consumed the most skilled weavers.

The beardless guide led him through several more chambers before ushering him into a tiled courtyard which looked out over the gardens. A small fountain stood in front of the tiles, with a goanna statue releasing water.

A man reclined on a cushioned bench, watching the fountain. He rose as Balanada drew near, then nodded slightly. The trading-captain bowed low in response, with his gaze fastened on the ground for a moment.

As he rose, Balanada studied the other man. He appeared only half like a true man of Aururia. His skin was darker, and he had curly hair, too. The marks of someone whose mother was a slave, though from somewhere different to the more commonplace slaves, whose skin tended to be lighter.

Nothing about being born of a slave mother would matter to the Atjuntja nobles, of course. So Balanada had learned, over several visits. To an Atjuntja aristocrat, a son was a son, regardless of who his mother was, or whether marriage vows had been spoken.

The man said, “I am Googiac son of Yageggera, and kin to the King of Kings.”

“Honoured to meet you,” Balanada said, with another deep bow. “I am Balanada of the Liwang, from the Island, here in harmony.”

This Googiac overstated his family’s importance, probably. Every Atjuntja aristocrat could claim some blood relationship to the King of Kings. One of the older monarchs, Kepiuc Tjaanuc, had been a prolific breeder, even by the standards of the many-wived Kings of Kings. Most of the Atjuntja nobles had married one or other of his descendants. So had many of the non-Atjuntja nobles, come to that.

Googiac said, “I have met many men of the Island, but you are the first of the Liwang I have spoken to.”

“My fellows have brought many ships to the White City over the years, and this is not my first visit. Unfortunate that we have not met before, for we always bring much of value for trade.”

“Let us not speak of commerce yet,” Googiac said, and gestured to another of the cushioned benches in the courtyard, nearest to the one which he had been using. “I would know more of you and your kin first.”

“As you wish,” the Islander said, with another slight bow, before settling down into the chair.

“Do you have a family?”

“A wife, Warramuk. We have no children yet,” Balanada said. Nor would they until Warramuk was satisfied of the security of his wealth, which meant at least one successful trading voyage, if not two.

“Tell me more of her,” Googiac said.

The conversation went on, about his family, and Googiac’s, and then shifted to other innocuous topics. They even spoke briefly of which birds visited the garden, with the aristocrat declaring that his favourite birds were the two kinds of black cockatoos which rarely visited. He had heard of some Atjuntja aristocrats who preferred to know more about men before they agreed to commerce, but never met one such. Of course, this man was the son, not the head of the family.

In time, Googiac said, “When you came, you said that you were here in harmony.”

Balanada shook his head. “The Good Man taught that we should foster balance and harmony with all of those we meet.”

“I have heard several Islanders speak of balance and faith. Though they most commonly sought to persuade me to adopt their faith, as if I were out of balance.”

“My counsel to other Islanders has always been not to tell any non-believers that they lack balance,” Balanada said. Even if it was true, calling a pagan unbalanced would never please them.

Though this entire land is out of balance. Teegal had become a much-troubled, uncertain country, and some of their people had begun to look for the causes. For so long the Atjuntja rulers had forbidden the Nangu from telling their subjects about the true path, but that prohibition was as dead as the power of the King of Kings. There still was a King of Kings here in Witte Stad, but he could give no command unless the Nedlandj governor approved it.

Now...some of the Atjuntja, and their subjects, had asked men of the Island about the true path. The Nedlandj neither helped nor hindered that effort. But then, the Nedlandj cared very little about the true path, and indeed cared little about what the Atjuntja believed. Though they had suppressed the worst of the Atjuntja’s customs of sacrifice. Some Atjuntja were still sacrificed to the pain, but none to the death. Or not in public view, at least.

So whatever the reason, the Nedlandj did not interfere with the Islanders speaking of the true path. While the King of Kings no longer could interfere. That left the Nangu free to speak of the true path... and they did.

“As may be,” Googiac said, apparently unconcerned what Islanders thought of him. “It is intriguing, though, is it not, how many peoples have faiths with so much in common. My forefathers taught of the liquid harmony which pervades the cosmos. You Plirites and Tjarrlings speak of harmony and balance. Even the Cathayans speak of the cosmic balance of the Dao.”

“The Good Man was the first to glimpse the whole truth, but it is inevitable that others will have imperfectly recognised parts of it.”

“So you would say,” the aristocrat said, with a smile. “And doubtless the followers of the Dao would claim that theirs is the true path, while yours is merely an imperfect reflection of it.”

“I have never met a Cathayan,” Balanada said. Nor did he have any real interest in doing so, particularly if it meant sailing too far from the Island.

“I have met several, though none yet who know enough of a useful language to find out more of what they believe,” Googiac said. “But with so many ways of looking at the truth, that suggests to me that we need a tametja to truly understand.”

“Tametja? I know not that word in your tongue.”

“A… new way, you would say, in the speech of the Island.”

The old way was good enough for Balanada, though he would not risk offending his host by saying so. “There are many roads to the truth.” Which is true, it is just that only one road truly arrives there.

“A point to consider. I would like to speak more about what you believe, before your ship departs Teegal. First though, we can speak now of matters of commerce.”

“Gladly. My ship carries a considerable cargo.”

“Oil of black fish [whale oil], hair of black fish [baleen / whalebone], smoked meat, duranj [gum cider], and several dyes. Or so the port officials claim.”

Balanada smiled. “Doubtless if they reported that much, they also described which dyes.”

“Sea purple. Electric orange. Some kind of blue dye which is not indigo.”

“Tjibarri blue. A vivid blue pigment which the men of the Five Rivers have discovered recently. They mine it from a deposit near Gwee Langta [Broken Hill]. Cheaper than indigo. It can dye cloth, or be used as a splendid paint. Though not as versatile a dye, since it cannot be made into yellow or green.”

Googiac looked out at the fountain before replying. “My family may perhaps make some use of that, for the right price. Which deserves the next question: does your ship carry anything which the port officials did not claim?”

“My ship contains some compartments which are difficult to find,” Balanada said. “Those compartments are not empty.”

“Speak on.”

“It is unfortunate that I cannot declare all of my cargo openly. Yet the Nedlandj have the power over trade, so I must be discreet.”

Googiac laughed. “You do not understand where the power lies in the Middle Country.”

“I would welcome enlightenment.”

“The King of Kings is powerless. The Nedlandj broke him, and now he rules only at their sufferance.”

“That much is known even on the Island,” Balanada said. “So the Nedlandj rule Teegal as they wish, including on trade.”

“No. The Nedlandj are too few, and too far away. We nobles rule the Middle Country. The Nedlandj have the power to break any individual noble. But not the power to break all of us.”

Balanada smiled again. “So...?”

“So, we of the blood pure wish our pleasures: kunduri, sandalwood, gold, and other things. What we wish, we obtain. If the Nedlandj tried to stop the smuggling in truth, they would find all the nobles opposed to them – and they would not find the Middle Country so easy to rule.”

“Why the rules, then?”

Googiac shrugged. “It stops the common man from trading those goods, save those with a noble benefactor, and keeps the Nedlandj from losing too much wealth. But they cannot stop the nobles. Nor have they tried. Or not in any way that matters.”

“Then let us speak further of trade,” Balanada said.

* * *

[1] These are historically known as Breaksea Island and Michaelmas Island on the outer edge of King Georges Sound.

[2] The dye which Aururians call sea purple is made from the large rock shell (Thais orbita), a relative of the Mediterranean sea snails (Murex) that produced blue-purple dyes that were extremely valued commodities in antiquity. Sea purple remains a very expensive dye within Aururia even after European contact, though it is mostly used within Aururia rather than exported elsewhere. It is particularly popular with the Tjibarri elite because it is one of the colours (together with orange, brown and pink) which are not associated with any faction.

[3] That is, tobacco grown from various native Aururian Nicotiana species, not the domesticated tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) that originated from the Americas.

[4] Bloodroot, historically also called meen or mean, has the scientific name Haemodorum spicatum. It is a small black-flowered plant with an edible red tuber which gives the plant its name. The tuber contains a hot-tasting red substance which can be used fresh, or extracted in oil and then dried to use as a more concentrated spice. The culinary heat produced depends on the cultivar, with some as mild as (true) peppers and others nearly as hot as chilli peppers. Various parts of the plant can also be used to produce natural dyes, such as green produced from the leaves and stems, and pinks and purples produced from the bulb. However, only dye extracted from the seeds – which produces a serviceable red colouring – can be preserved in a form which is suitable for export.

* * *

Thoughts?