You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Lands of Red and Gold, Act II

- Thread starter Jared

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 71 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Lands of Red and Gold #122: A Man Of Vision Lands of Red and Gold #123: What Becomes Of Dominion Lands of Red and Gold Interlude #5.5: Interview With The Eʃquire Lands of Red and Gold is now published! Aururian Fire Management Lands of Red and Gold Interlude #15: Into Darkness Contest - Guess The Character Lands of Red and Gold Interlude #16: Minutes Take HoursJared this was - for the admittedly atypical me - one of the most enjoyable and fascinating posts I've read in years.

Thank you.

Indians. In Northern Australia. Four thousand years ago.

Amazing.

Thank you.

Indians. In Northern Australia. Four thousand years ago.

Amazing.

We don't usually get updates on alternate genetic groups of humans (mind you, most TLs don't go back that far).

twovultures

Donor

The larger presence of Denisovan DNA in Australia is fascinating, and I'm glad you found a way to incorporate the discovery of Indian contact with Australia into the timeline.

That's part of why I proposed the development of a northern Australian agricultural package in the Potential Domesticates thread, it would be really cool to explore Indian/Austronesian contact with farming Australians. I hope you have a sequel in you

That's part of why I proposed the development of a northern Australian agricultural package in the Potential Domesticates thread, it would be really cool to explore Indian/Austronesian contact with farming Australians. I hope you have a sequel in you

A truly fascinating update.

Just stumble on an article that claims that the Denisovians had genes from an older human species.

http://www.newscientist.com/article/dn24603-mystery-human-species-emerges-from-denisovan-genome.html

Just stumble on an article that claims that the Denisovians had genes from an older human species.

http://www.newscientist.com/article/dn24603-mystery-human-species-emerges-from-denisovan-genome.html

The Tjagarr Panipat comes from a Gunnagalic phrase meaning "Place of Great Disputation". This is a prestigious university (well, among other things) which is located in the Five Rivers / Murray-Darling basin. The Panipat claims to be Aururia's oldest university.

Cool.

Way cool.

Unfortunately I suppose this suggests that using OTL Australian linguistics and culture for southeastern Aururia was off, and actually they'd likely have been nigh on unrecognizable.

Although those people hiding out in southwestern Tasmania in TTL might be an exception.

Although those people hiding out in southwestern Tasmania in TTL might be an exception.

Jared this was - for the admittedly atypical me - one of the most enjoyable and fascinating posts I've read in years.

Glad you liked it.

Indians. In Northern Australia. Four thousand years ago.

Amazing.

Yes. When I found out about that, I had to incorporate it somehow.

We don't usually get updates on alternate genetic groups of humans (mind you, most TLs don't go back that far).

Yes, this is one of these topics where it's hard to make changes without butterflying humans away completely.

Hard, but not quite impossible.

That's part of why I proposed the development of a northern Australian agricultural package in the Potential Domesticates thread, it would be really cool to explore Indian/Austronesian contact with farming Australians. I hope you have a sequel in you

A tempting idea. But given LoRaG has taken about 5 years and has only gotten to about 30 years after the PoD, how long do you think it would take to even beginning a sequel?

Just stumble on an article that claims that the Denisovians had genes from an older human species.

The Denisovans were indeed a funny bunch - and made even more mysterious because we know very little of what they actually looked like. We know more about the Denisovan genome than we do about even what their skull looked like.

In terms of their interbreeding with even older human species, what is interesting is that the estimates for Denisovan nuclear DNA suggests that they split from the ancestors of modern (African) humans around 800,000 years ago, but the mitchondrial DNA sequences suggests sometime over a million years. Which in turn means either that the Denisovans preserved an older human lineage which was wiped out in other human branches (Neanderthals, Homo sapiens) through random drift, or that their mtDNA comes from the same even older human species which it looks like they interbred with.

So in other words, although ATL Aururians will be credited as having preserved mtDNA from the Denisovans, in fact they may have preserved it from an even older species.

Unfortunately I suppose this suggests that using OTL Australian linguistics and culture for southeastern Aururia was off, and actually they'd likely have been nigh on unrecognizable.

Probably not as much as it might appear on first impression.

Certainly the exact languages or cultures will have changed, at least on the mainland. That was more or less certain anyway, due to lepidopterans.

But in terms of linguistics, all of OTL Australia - even Tasmania - formed a Sprachbund. That is, due to so long being in the same areas, even unrelated languages picked up similar features in terms of phonology, grammar, syntax etc. These common rules, or similar ones, will probably be around ATL too - they go back a very long way. There's no evidence that the influx of Indian genes was associated with any changes to those language rules - there's no relationship between Australian languages and Indian languages, and Tasmanian languages, as far as we can tell, are included in the Sprachbund despite 10,000 years of isolation.

And it was those rules which I used to create the ATL Aururian languages: rules such as no fricative sounds, and so on. I did not base the ATL languages on any actual OTL language in terms of grammar, word roots, or anything like that. I used a few actual words from OTL languages, but that was just to represent the right kinds of sounds, not words which had the same meaning - I assigned other meanings entirely to those words. (With one exception, the Junditmara, but see below).

The case of culture is more complex, but the available evidence is that cultural continuity in Australia continued to a strong level despite the shift to Pama-Nyungan languages. While no-one's sure of exactly why the Pama-Nyungan languages spread, it does not appear to have involved wholescale cultural replacement, or anything like that.

To pick two examples, in Victoria, at the far end of the continent from the Pama-Nyungan homeland, the OTL Gunditjmara aquaculture (which the ATL Junditmara are loosely based on) goes back 8000 years or longer, much older than the spread of Pama-Nyungan (which started about 5000 years ago or more recently). There's also quarries/ mines which were regularly used in Victoria for the last 18,000 years. Given that degree of cultural continuity, and the likely spread of butterflies (which start, say, 10k years ago) I can live the idea of there being someone in the OTL Gunditjmara lands who ITTL maintained aquaculture. Not the same culture overall, of course, but still following the ancient aquaculture practice

Similar things apply to the religious beliefs across the continent ("the Dreamtime" and so on), which while not identical, show a common outlook which also goes back quite a long way. Likewise the division into things like skin moieties (which I based the kitjigal on) are things which show up in non-Pama-Nyungan languages just as much as Pama-Nyungan ones, and so pre-date the split.

Obviously, the details are different in all forms - ATL Aururian religious beliefs are dissimilar to OTL ones, and the kitjigal follow different rules and have entirely different totems - but as a general source of inspiration, I think that they're still acceptable.

Although those people hiding out in southwestern Tasmania in TTL might be an exception.

I had kept the Tasmanians as a separate culture which was largely safe from the butterflies until the mainland invasions of the last thousand years. That's why their languages and even name for themselves (Palawa) is much closer to what they were historically.

So if a fossil is reclassified as a hominid the paleontologist who originally described it will them also become retroactively classified as an anthropologist?\

Nah, they'll just have contributed to anthropology. It's usually pretty clear though, I mean you are describing it so you'll realise it's human-y remains and hand it over (at least in part) to an anthropologist.

I do like the confusion they're acting under, but I'd find it far more intriguing to see the guesses that would be made in these circumstances. Because that's what they would do, of course: speculate to fit the facts.

Perhaps they assume a human culture of two species - with roles divided between the two but interbreeding entirely taboo. If you assume such a culture could preserve a separate population at all, and that the system later broke down, then that would explain how the genes would fail to appear elsewhere in Australia or New Guinea.

Or maybe they would think that some hominid escaped Africa to some Indian Ocean island or other, then managed to get to Australia long after it was settled, before extinction through intermarriage. And on reflection, as ludicrous as that theory is, it's not much stranger than the factual thing with the bronze-age Dravidians.

Perhaps they assume a human culture of two species - with roles divided between the two but interbreeding entirely taboo. If you assume such a culture could preserve a separate population at all, and that the system later broke down, then that would explain how the genes would fail to appear elsewhere in Australia or New Guinea.

Or maybe they would think that some hominid escaped Africa to some Indian Ocean island or other, then managed to get to Australia long after it was settled, before extinction through intermarriage. And on reflection, as ludicrous as that theory is, it's not much stranger than the factual thing with the bronze-age Dravidians.

How will the scientists of this TL tie this genetic info in with the misconceptions you mentioned about the origins of the Australians you mentioned (tieing them in with Aztecs&Easter Islanders, etc)

By the time the genetic data comes along, the serious scientists will long since have discarded the misconceptions that suggested contact with Easter Island, the Aztecs, or ancient Egypt.

Cranks of the Chariots of the Gods ilk will not have given up on the idea. But people of that mindset aren't going to let their pet theories be challenged by such minor details as actual evidence.

Given the recent update you might find this of interest Jared.

Interesting link; thanks. It's a useful reminder that people moved around a lot in the prehistoric era.

I do like the confusion they're acting under, but I'd find it far more intriguing to see the guesses that would be made in these circumstances. Because that's what they would do, of course: speculate to fit the facts.

Good point. I may have to write up a sequel to this post, showing what the various forms of speculation looked like.

As well as the possibilities you suggest, other theories would be that there was some hominid which entered Australia long before H. sapiens, but which was sufficiently "primitive" that it did not modify the environment very much, and only with the flood of modern H. sapiens was there both extinction of the megafauna and intermarriage with this ancient lineage, who lived far enough in the south (maybe not used to the heat with the ending of the Ice Age?) that the interbreeding did not spread to New Guinea.

Lands of Red and Gold #77: The Raw Prince

Lands of Red and Gold #77: The Raw Prince

Serpent's Day, Cycle of Brass, 11th Year of His Majesty Guneewin the Third / 25 December 1643

The Highlands [near Talbingo, New South Wales]

A breeze blew along the river valley, stirring the oil-leaves [eucalyptus leaves] up from the ground into lazy swirls. Leaves that blew in the wind; in a wind that blew from the north.

As always, whenever he felt a wind that blew from the north, an old song came to his mind. Words that had been etched into his psyche, first heard long ago in childhood and never forgotten.

“Northerly blows the wind,

Dry becomes the air,

The heat is no friend,

While wild fires flare.”

The words of warning were ancient. A northerly wind meant that it came from the red heart, the blood-coloured, parched soils of the northern deserts. A wind that brought heat and stirred the ever-present risks of fire.

A wind that brought fear, but also a wind that he had never forgotten. He had lived many years since he had first heard the song, he had travelled much and accomplished much, but he had never forgotten it. For this reason, as much as any other, he asked men he met to call himself Northwind. Or, rather, that was the most frequent name he had them call him.

The men around Northwind shifted slightly when the breeze gusted stronger. But their countenances showed nothing of the acknowledgement that a northerly wind would bring to a lowlander. Understandable, of course. They would have their own songs, their own legends which would drive the course of their lives, but they would be different, as such songs were for each people.

Seven men surrounded him. All highlanders. Crudely-dressed, barbarously-presented men. All of the men had long, unkempt beards, except for their clean-shaven chieftain. Black hair grew long for all seven men, crudely fashioned into dangling braids, except for the chieftain whose hair had been knotted into two buns, one above each ear.

The highlanders had dark skins, if not as dark as the typical Yadji. Their skins seemed even darker when measured against the patterns of white and red ochre daubed onto their faces and arms. Four of the men had some form of jewellery, bracelets, bangles, necklaces or hair adornment. All of them carried weapons; a motley collection of swords, spears, bows, daggers, and hammers.

The chieftain answered to the name of White Crow. Northwind wondered, briefly, why the chieftain would choose the name of something that did not exist. Not something that he could ask about at the moment, but he made an air-clay inscription [1] to find out later. His efforts to understand people were what had made him the man he was today.

White Crow had bangles on each arm. His necklace was shaped from finger-bones with holes drilled into them to fit the black cord that held them together. Northwind did know the reason for that necklace, since it was part of the tale which had brought him to choose this chieftain. White Crow gathered his necklace because he ensured that anyone who challenged him always lost something from the process.

“You have asked, floodlander, and so we are here,” White Crow said.

“I am here because word of your deeds precedes you,” Northwind said. He dipped his head and raised his palms; the highlander gesture of respect.

Tales of the highlanders had long preceded them in the Five Rivers. Rare was the highlander raid that reached Tjibarr’s soil, but their incursions were common in the more easterly kingdoms. Of course, Northwind only knew about White Crow himself because he had asked enough questions of the right people. Among asking many other things, naturally.

“Words are empty wind. Gifts and deeds are real. Which of those do you bring?” White Crow asked. The chieftain spoke the Wadang tongue [the language of Gutjanal], which Northwind also spoke passably well. He was not fluent in the tongue, but then neither were these highlanders.

“Gifts which will aid your deeds,” Northwind said.

Accomplishments mattered to these highlanders, clearly. Even more than he had realised when gathering songs and tales of these people. Songs, most of all. Northwind always tried to find out as many songs as he could about any new people, so that he could better understand them.

Before he arrived, he had discovered only one highlander song. That song was written by a highlander chief’s daughter a hundred or more years ago. She had been married to a Gutjanal Elder for reasons which were no longer recorded. That woman had composed a lament for her old homelands, a song which had been widely repeated in Gutjanal, and had even reached Tjibarr.

“Ten years I have been in the lowlands

And every night I dream of the hills

They say home is where you find it

Will this city ever fulfil me

I come from the high country people

We always live in the hills

Now I’m down here living in the floodlands

With this man and a family

My highland home, my highland home

My highland home, is waiting for me.”

That song had been a revelation for Northwind. He knew – everyone knew – how much the highlanders coveted the wealth of the lowlands. That was why they raided them so often. But he had imagined that meant that they preferred life in the comfort of the lowlands, too. The woman’s lament – she had a name, but he could not recall it – had taught him otherwise.

Proof, once again, that songs were the key to understanding people.

The man who called himself Northwind had been given a true name for himself once, so long ago. His mother had given it to him, but he barely remembered the name or her, any more. He did not like even to think of himself as having a true name. That made it more difficult for him to remember the new names he adopted for himself. But if he had to choose a name for himself, one he never repeated to others, he would call himself Songfinder. Finding songs was the best way to understand people, and understanding them made it much easier to mingle with them, obtain information from them, and accomplish what he needed to do in his life.

The chieftain was silent for a time, as if waiting for Northwind to give in and explain what gifts he brought. A waste of time, that; Northwind could be as patient as needed. Particularly when arrogance was part of the persona he had adopted here.

“My deeds are legion. So the tales will have come to your ears. What can you offer to make my deeds any greater?”

“My couriers” – Northwind gave a languid wave to the north, downstream along the river – “have with them many of the thunder-weapons the Raw Men use. Doubtless you have heard of those weapons.”

“I have,” White Crow said, keeping his tone and expression neutral with better self-control than Northwind had expected from a hill-man. Certainly his retinue lacked his restraint; eagerness was evident on their faces.

“The thunder-weapons I could sell to you, if they interest you.”

“That could be done, for the right price.” The chieftain kept his tone neutral still, but his breathing had become ever so slightly faster. Not something that many men would notice, but Northwind had learned his craft in Tjibarr itself. White Crow might have more self-control than rumour attributed to highlanders, but he lacked the sophistication of one shaped by the politics of the Endless Dance.

“The price is only part of what I require from you, before I will sell you these weapons,” Northwind said. He made his tone as overbearing as he could manage. He only wished that he could speak Wadang more fluently, to choose the most arrogant words to suit his tone. “I have a further condition.”

“Name it.”

“The thunder-weapons must be used on the Yadji. Them alone. Strike them with all the prowess that has made your previous deeds so widely renowned. Raid the Yadji with these weapons, and not anyone else. That is what I require of you, in addition to the price we agree for me to have my couriers bring the weapons to you.”

White Crow regarded him with narrow eyes; a long, silent glare that made Northwind wonder for a moment if he had pressed the arrogance too far. At length, the chieftain said, “This may be something I could accept, if the price is fair.”

“Then let us talk us consider prices,” Northwind said. He settled down into a bargaining session where his biggest challenge was ensuring that he haggled hard enough to prevent the highland chieftain becoming suspicious. For the truth was that while Northwind could bring back some sweet peppers as a small recompense for the price of the muskets, he cared naught if he brought back nothing.

This will work, Northwind decided. His façade of arrogance, and his blatant demands, would have the desired effect. White Crow would fear loss of his prestige amongst his own people if he held to such an agreement. The chieftain would surely make some raids on Gutjanal or Yigutji using the muskets, to prove to his own people that he was not a puppet of the lowlanders.

In turn, such raids would increase suspicion between Gutjanal and Yigutji, each of whom would blame the other. They would accuse the other of smuggling weapons, and mistrust would fester. Not enough to fight each other, hopefully; both kingdoms had more fear of the Yadji and their foreign Inglidj backers. But enough tension to keep the two kingdoms more wary of each other than of Tjibarr.

Better still, if anyone in the eastern kingdoms figured out that someone from Tjibarr had smuggled the muskets, and if they somehow persuaded the highlanders to describe the smuggler, why, they would find only a description that matched a known agent of the Whites. The blame would fall there. Or even if they realised that the smuggler had been someone in disguise, they would not blame the Azures, the faction which had been most staunchly against the proposal to smuggle weapons to the hill-men.

And even if by some chance White Crow held to his agreement and only raided the Yadji, well, even that would help when war came with the Regency. With this blow, the Azures cannot lose.

* * *

10th Year of Regent Gunya Yadji / 19 September 1646

Baringup [Ravenswood, Victoria]

Durigal [Land of the Five Directions]

A dog sat motionless in front of Prince Ruprecht. Rather an impressive dog, he thought. Sturdy and compact, its muscular frame radiated an aura of dextrous strength. It had pricked ears set far apart, with a broad head that flattened between its dark, alert eyes. Its shoulders were compact but well-muscled, with straight, strong legs. Its fur appeared rust-red on first impression, but when he looked more closely he saw that its coat was a mixture of darker-red and white hairs.

The dog remained perfectly still as Ruprecht conducted its inspection. Its eyes followed him, but its head and body did not move.

“Discipline, by God!” Ruprecht said. Proper discipline. Rare enough in men, and almost unheard of in animals.

The Yadji handler barked a word in his own language, one that Ruprecht did not recognise. The dog stood and then adopted a crouching posture, keeping its head and shoulders lowered and moving forward slowly as if it was slinking.

“This is how the dogs herd noroons [emus]?”

The handler shook his head. “Yes. No dogs or men can do it better.”

Having seen noroons in a field, Ruprecht could only agree. The big flightless birds made good eating, but were devilishly hard to herd. They ran on their own rather than together, could move at more than twice the speed of a man, and change or reverse direction without slowing down. The birds made moving sheep or cattle appear effortless by comparison.

A well-trained, adept herding dog like this one would be invaluable to farmers. But even more pleasing to Ruprecht. Which was, no doubt, why the handler had brought it here. He suspected that every man in the Yadji empire knew of his fondness for his boxing gupa [kangaroo], Sport. The handler would be seeking similar reward.

And, perhaps, the dog had been sent here as a distraction by the Yadji nobles. Some of them knew of his growing dissatisfaction with being trapped here while the Yadji emperor adhered to a pointless truce with his native enemies.

“What is the dog called?” the prince asked.

The handler gave a name, another Yadji word which Ruprecht did not understand.

“Will he answer to another name?”

“In time, my prince. And he answers to commands in word or gesture.”

“Splendid. I prefer a name I know. I will call him... Boye.”

The Yadji handler bowed. “I can assist you with training him to obey you.”

“Of course,” Ruprecht said, though his thoughts was elsewhere. Boye had been meant to keep his mind diverted, he was sure of it. “I will send for you again soon.”

The handler showed himself to be more alert than most of his countrymen, for he bowed again and withdrew.

“Well, Boye, what am I to do with you?” Ruprecht asked, switching to German. No-one was near enough to overhear, but he used that language anyway. Too many of the Yadji understood English nowadays.

The dog looked up at him. Incapable of giving an answer, perhaps. But alert all the same.

“Your people want me to spend the next two years waiting. No gold, no glory, no action. Even if the war restarts after that, I have nine hundred soldiers who want war and prizes, not inaction in a kingdom of savages. Should I put up with that?”

The dog looked at him, and gave a slight whine. So Boye understood the question, even if he could not answer it.

“I agree, Boye. This is not right. I have to take my soldiers somewhere. But where?”

Ruprecht waited, but Boye did not offer any opinion.

“Only two choices. Well, three, but I’m not going to go back home yet. One choice is the island across the waves, which these savages call the Cider Isle. A place of gold and war, by all accounts. The Company is sponsoring one kingdom of savages to fight the other. Plenty of opportunities there, for crack cavalry, good Christian soldiers, who have the discipline to kill savages.”

The dog whined and dropped its head.

“Maybe you’re right,” Ruprecht said. “Plenty of gold, but not many Company ships to take the men across, and I wouldn’t trust these native ships with your neck, never mind mine. And I doubt these savages speak the Yadji language. Learning one heathen tongue has been enough work; I don’t want to have to start all that again. Or waste the rank I’ve built up with the Yadji.”

Boye kept his head down, but made no other comment.

“One other choice, I think. Far to the east of the Yadji realm, their subjects are growing restless, I hear. Gurnowarl, they’re called, or something like that. A display of good horseflesh will convince them to stay under the thumb. And if they rebel while we’re over there, then not even these Yadji savages can stop us looting while we’re putting them down.”

Ruprecht looked down, but Boye remained stolidly silent. “Better yet, after that, there’s the highlands. Home to barbarians so bad that even these savages call them savages. Raids have picked up. Bringing the highlanders to heel, now that would be something worth accomplishing.”

“And I’m sure I could persuade a few hundred of their infantry to accompany me.” Foot could not stand up to proper cavalry, but they made a useful anchor in battle all the same. And he would need to garrison the towns he conquered. “Less gold, maybe, but more glory. The Yadji Emperor should give me a golden handshake for quelling the highland savages. More gold than anything in the Cider Isle, I hope.”

“Or perhaps not. Trust not to gratitude of princes, it’s said. What do you think, Boye?”

Ruprecht held up a hand. Boye looked up at him, and barked twice.

“Yes, I think you have the right of it,” Ruprecht said. “The highlands call.”

* * *

Azure Day, Cycle of the Sun, 408th Year of Harmony (3.23.408) / 12 December 1647

Hanuabada, Rainy Island [Hanuabada (“Big Village”), Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea]

Clouds built up on the western horizon, but so far no rain fell. Fortunate. Yuma Tjula was still not entirely familiar with the rhythms of these northerly lands, despite living here for five years, but it had not taken him long to learn the time of the wet season. The time of so much rain as to be unnatural. And that season held true as much on this rainy island as it did in his new home across the Coral Strait in Wujal [Cooktown, Queensland].

With the air still clear, picking out the arriving ships was easy. Five lakatoi, as the locals called them. The vessels were really multi-hulled canoes rather than properly-made ships, built and rebuilt after each voyage. But they were still large enough to carry considerable cargo. Some of the locals were wading out into the water to greet the arriving lakatoi.

Yuma turned his gaze away from the sea and ships, to face the man standing beside him on the sand. Werringi the Bold. A man from a rival bloodline, that now worked in cooperation with his own. Between them, they had forged the trading association, the nuttana, that offered new hope where the Island had failed. Six bloodlines had now joined the association, but Werringi and Yuma remained the heart of the nuttana. If they supported a venture, it would be accepted. If they opposed a venture, it would be rejected.

“How far have those ships sailed?” Werringi asked.

“Across the great bay [Gulf of Papua], no more. Not a bold voyage” – both men shared a grin – “but these Motuans are a trading people, all the same.”

“Clay pots for crops and timber.” Werringi nodded. “Odd to think of clay as an item worth trading. But then where there is need, there is commerce.”

“Or where there is greed,” Yuma said. He gestured, and they started walking along the sand toward the town, with its big houses on stilts. “Most of their crops are worthless. Rabia [sago] is bland and bulky. Too far to sail for food, too.”

“Useful if famine threatens closer to home.”

“Perhaps. The headhunters who farm it seem to have plenty to spare, with how much they give to these pot-makers. But the tohu [sugar cane], this is what matters.” Yuma smacked his lips.

“So I’ve known, since I first found it in Batabya [Batavia],” Werringi said dryly. “But knowing that and getting the crops and workers to make use of it are two different paths.”

“Both can be found here on the Rain Island.”

“The tohu, yes. The same, or nearly. But the workers? These headhunters know not metal. Or much of anything else. Can they boil it properly and gravel [crystallise] it as the Nedlandj do in Batabya?”

“Not that I have seen. But they can grow it. That is enough to begin,” Yuma said. “Even the taste of the sweet juice is reward enough. You can see for yourself soon.”

Sure enough, the curly-haired locals brought several long stalks of tohu: thick, jointed, and coloured a dull red-brown. One of them demonstrated for Werringi how to cut off a joint of the stalk and then cut it open to extract the pith in the centre, and chew it.

Werringi used his own knife to cut off another joint of the stalk, and then put it in his mouth. After a brief moment’s chewing, he grinned. He did not speak, not with his mouth full of tohu pith and juice, but then he did not need any words.

Yuma said, “We must invite some of these Motuans, or their headhunting friends, back to Wujal. To bring this tohu with them, and grow it there.”

As Yuma had expected, Werringi shook his head in vigorous agreement.

* * *

The highlands of Aururia: a thinly-populated region inhabited by peoples who seemed to take in warfare with their mother’s milk. Raiding and plundering was a way of life for them; in a land where resources were scarce, many people found it more useful to take what others had produced rather than develop their own. The highlanders happily fought each other, but they would gleefully raid into the lowlands. The Five Rivers had been their prize target for hundreds of years, but in the last couple of centuries they had become equally fond of paying armed visits to Yadji lands.

Counter-invasion of the highlands proved difficult, mostly because there was little worth raiding. The highlands were lands of scattered farms, filled by people who knew how to cache food to keep it secure from both the natural ravages of flood and fire and more human-induced depredations. The handful of villages and towns were mostly places where people came temporarily for markets or celebrations; burning them or looting them would barely hinder the hill-men’s capability to resist.

Highlanders would rarely fight stand-up battles without being forced into them, and they were adept at using their knowledge of the local countryside to evade pursuit. Invading forces were plagued both by the lack of accessible enemies to fight, and the difficulty in obtaining sufficient supplies. Some commanders would withdrew in frustration, while more successful ones would demand some level of tribute which was enough for them to proclaim victory before they discreetly withdrew, too.

Prince Rupert, Duke of Cumberland, knew little of this long history. What information he had gathered about the highlands told him of their success at raiding, but little about the extreme logistical difficulty of suppressing them. Rupert believed, with some grounds, that his cavalry would allow him to chase down hill-men who tried to flee on foot. Quite how he would feed those same cavalry was a question he did not consider in as much detail.

Prince Rupert had also expected that the Yadji rulers would provide only lukewarm support for his expedition. This expectation was only testament to his misunderstanding of a people he still viewed as savages. The Regent Gunya Yadji and his leading generals were enthusiastic in commending “Prince Roo Predj” for his valour in proposing to quell the highland savages.

For the Yadji, Rupert’s departure was a three-fold blessing. Firstly, it would let him indulge his plundering instincts in territory which the Yadji cared nothing about. Secondly, it gave them the opportunity to send some inexperienced infantry with him, so that they could gain military experience before the truce with Tjibarr expired. Thirdly and most importantly, it removed the risk that his growing boredom could lead him to break that same truce.

So Prince Rupert found himself leading nine hundred European cavalry and fifteen hundred Yadji infantry. The horsemen were all veterans of the late European war and the first fighting in Prince Rupert’s War. The infantry were mostly newly-trained troops, with a smattering of veterans distributed throughout them in Yadji style, to teach them and stiffen their resolve.

He had two objectives in mind. Firstly, to make a grand march along the Yadji royal road to dismay the rebellious Kurnawal into submission. Secondly, to impose a string of stunning victories on the highlanders and quell them into submission, too.

Rupert’s first objective was a success. Horses were unknown in the eastern regions of the Yadji realm, and the grand procession of cavalry and infantry alarmed the Kurnawal, who were indeed growing rebellious, a decade and a half after the last time the Yadji had suppressed a rebellion.

Rupert’s second objective... was not such a success.

The high country taught the German prince, as it had taught so many before him, that it was one thing to build an army which the hill-men could not defeat in battle, but quite another thing to build an army which could eat trees and grass. Even for the four-legged part of his army that could eat grass, the rigours of daily marches seldom left the horses with enough time to replenish their energy by grazing at night. And strangely enough, their highlander hosts had thoughtlessly neglected to provide fodder for their equine visitors to replenish their strength.

Rupert’s cavalry could indeed do as he had expected, and run down any highlanders caught in the open. Which would have been more helpful if the highlands had more open ground to work with. Foot soldiers, he found out, could outrun horses in a place where the best roads were only muddy tracks, and when in most areas the hill-men did not have far to flee before they reached the sanctuary of trees. Where ambushes with archers or sometimes muskets were an ever-present threat, his cavalry could proceed only cautiously through forest, which gave the hill-men plenty of time to escape.

The bigger challenge was, of course, food. The prince had his soldiers burn the first couple of towns they occupied, but that did not bring the highlanders out to battle. He occupied the third town he found, but that only worked until the food ran out and most of the inhabitants vanished into the night.

The only way the invading army could survive in the highlands was to keep moving, squeezing what supplies they could from the scattered highland farms before their inhabitants hid their food and fled. This was an army continually on the march, unable to camp in one location for more than a few days. Even maintaining that kind of campaign would have been impossible without occasional resupply sent by dog-travois caravans [2] from the Yadji realm.

The hill-men fought their own style of campaign against the invading forces. They preferred to raid at night, or ambush any scouts or screening forces. Prince Rupert soon learned to be thankful for the presence of Yadji infantry, for without them defending camps at night would have been almost impossible. The highlanders rarely concentrated their forces, both to avoid risking their too-few numbers and to keep from exhausting their hidden supply caches.

By halfway through the first summer, Rupert’s army had settled into a routine. March for a couple of days, then set up a camp with some timber fortifications where his infantry could provide a secure base. His cavalry would spend several days sweeping the surrounding countryside, trying to capture any highland raiders they found. If that failed – as it usually did – he would march on for a couple of days and repeat the pattern.

With the first snows threatening in the autumn in 1647, Prince Rupert withdrew to Elligal [Orbost, Victoria] to wait out the winter. He took up the habit of painting during that winter, using some of the spectacular colours which the Yadji made. Two of those paintings would survive into the modern era. Gunawan in Flood showed a broad view of the River Gunawan [Snowy River] in springtime flood, with his beloved Boye crouching in the foreground. The Great Executioner showed a Yadji death warrior in full battle garb.

In the second summer of the truce, Prince Rupert brought his forces back into the highlands. Little had changed from the first summer. The hill-men were even more cautious to avoid open battle. The largest conflict which he could proclaim a victory involved less than one hundred highlander casualties, although this death toll was in fact more severe for the manpower-deprived highlanders than Rupert realised.

As the summer progressed, engagements became even fewer. Rupert found that his visions of glory and gold were fading in the endless pursuit through the highlands. His frustration reached the point where he was prepared to listen to his native allies, who advised him to open negotiations with the highlanders before summer was over. He duly sent out emissaries, who reported that the highland chieftains were prepared to discuss terms for a truce.

Despite the galling truth that he would have little to show for two years of warfare, Rupert negotiated a truce with the highlanders. The terms were simple: for three years, the Yadji would not return to the highlands, nor would the hill-men raid into Yadji lands. The highlanders provided a gift of a truly copious amount of sweet peppers to seal the truce.

In a sign that he had learned a little basic diplomacy, Rupert responded by giving gifts of his own to the highlanders: a horse for each of the five greatest chieftains. These were given from among the stock of spare horses whose original riders had fallen in battle. Rupert took the precaution of choosing five geldings, as he had no wish to allow the hill-men to obtain breeding stock.

When he returned to Elligal, Prince Rupert declared his great victory over the hill-men. A victory that would not last past the next raiding season, for the highlanders had never been ones to treat truces as binding if they sensed weakness. The only real thing which Rupert gained from his highland endeavours was a taste for sweet peppers which would last for the rest of his life. From that time on, he regarded almost all food as too bland to bother with unless it had been properly flavoured with sweet peppers.

From Elligal, Prince Rupert quickly led his forces back west, to the heartland of the Yadji realm. For the two-year truce with the Five Rivers kingdoms was nearing its end, and he did not wish to be left neglected on the frontier when warfare resumed.

* * *

[1] “Make an air-clay inscription” is a Gunnagal metaphor which is roughly equivalent to “make a mental note”.

[2] The Yadji do, in fact, have wheeled vehicles, but they learned a long time ago that with the usual state of muddy tracks in the highlands, the older ways of travois were better.

* * *

Thoughts?

Serpent's Day, Cycle of Brass, 11th Year of His Majesty Guneewin the Third / 25 December 1643

The Highlands [near Talbingo, New South Wales]

A breeze blew along the river valley, stirring the oil-leaves [eucalyptus leaves] up from the ground into lazy swirls. Leaves that blew in the wind; in a wind that blew from the north.

As always, whenever he felt a wind that blew from the north, an old song came to his mind. Words that had been etched into his psyche, first heard long ago in childhood and never forgotten.

“Northerly blows the wind,

Dry becomes the air,

The heat is no friend,

While wild fires flare.”

The words of warning were ancient. A northerly wind meant that it came from the red heart, the blood-coloured, parched soils of the northern deserts. A wind that brought heat and stirred the ever-present risks of fire.

A wind that brought fear, but also a wind that he had never forgotten. He had lived many years since he had first heard the song, he had travelled much and accomplished much, but he had never forgotten it. For this reason, as much as any other, he asked men he met to call himself Northwind. Or, rather, that was the most frequent name he had them call him.

The men around Northwind shifted slightly when the breeze gusted stronger. But their countenances showed nothing of the acknowledgement that a northerly wind would bring to a lowlander. Understandable, of course. They would have their own songs, their own legends which would drive the course of their lives, but they would be different, as such songs were for each people.

Seven men surrounded him. All highlanders. Crudely-dressed, barbarously-presented men. All of the men had long, unkempt beards, except for their clean-shaven chieftain. Black hair grew long for all seven men, crudely fashioned into dangling braids, except for the chieftain whose hair had been knotted into two buns, one above each ear.

The highlanders had dark skins, if not as dark as the typical Yadji. Their skins seemed even darker when measured against the patterns of white and red ochre daubed onto their faces and arms. Four of the men had some form of jewellery, bracelets, bangles, necklaces or hair adornment. All of them carried weapons; a motley collection of swords, spears, bows, daggers, and hammers.

The chieftain answered to the name of White Crow. Northwind wondered, briefly, why the chieftain would choose the name of something that did not exist. Not something that he could ask about at the moment, but he made an air-clay inscription [1] to find out later. His efforts to understand people were what had made him the man he was today.

White Crow had bangles on each arm. His necklace was shaped from finger-bones with holes drilled into them to fit the black cord that held them together. Northwind did know the reason for that necklace, since it was part of the tale which had brought him to choose this chieftain. White Crow gathered his necklace because he ensured that anyone who challenged him always lost something from the process.

“You have asked, floodlander, and so we are here,” White Crow said.

“I am here because word of your deeds precedes you,” Northwind said. He dipped his head and raised his palms; the highlander gesture of respect.

Tales of the highlanders had long preceded them in the Five Rivers. Rare was the highlander raid that reached Tjibarr’s soil, but their incursions were common in the more easterly kingdoms. Of course, Northwind only knew about White Crow himself because he had asked enough questions of the right people. Among asking many other things, naturally.

“Words are empty wind. Gifts and deeds are real. Which of those do you bring?” White Crow asked. The chieftain spoke the Wadang tongue [the language of Gutjanal], which Northwind also spoke passably well. He was not fluent in the tongue, but then neither were these highlanders.

“Gifts which will aid your deeds,” Northwind said.

Accomplishments mattered to these highlanders, clearly. Even more than he had realised when gathering songs and tales of these people. Songs, most of all. Northwind always tried to find out as many songs as he could about any new people, so that he could better understand them.

Before he arrived, he had discovered only one highlander song. That song was written by a highlander chief’s daughter a hundred or more years ago. She had been married to a Gutjanal Elder for reasons which were no longer recorded. That woman had composed a lament for her old homelands, a song which had been widely repeated in Gutjanal, and had even reached Tjibarr.

“Ten years I have been in the lowlands

And every night I dream of the hills

They say home is where you find it

Will this city ever fulfil me

I come from the high country people

We always live in the hills

Now I’m down here living in the floodlands

With this man and a family

My highland home, my highland home

My highland home, is waiting for me.”

That song had been a revelation for Northwind. He knew – everyone knew – how much the highlanders coveted the wealth of the lowlands. That was why they raided them so often. But he had imagined that meant that they preferred life in the comfort of the lowlands, too. The woman’s lament – she had a name, but he could not recall it – had taught him otherwise.

Proof, once again, that songs were the key to understanding people.

The man who called himself Northwind had been given a true name for himself once, so long ago. His mother had given it to him, but he barely remembered the name or her, any more. He did not like even to think of himself as having a true name. That made it more difficult for him to remember the new names he adopted for himself. But if he had to choose a name for himself, one he never repeated to others, he would call himself Songfinder. Finding songs was the best way to understand people, and understanding them made it much easier to mingle with them, obtain information from them, and accomplish what he needed to do in his life.

The chieftain was silent for a time, as if waiting for Northwind to give in and explain what gifts he brought. A waste of time, that; Northwind could be as patient as needed. Particularly when arrogance was part of the persona he had adopted here.

“My deeds are legion. So the tales will have come to your ears. What can you offer to make my deeds any greater?”

“My couriers” – Northwind gave a languid wave to the north, downstream along the river – “have with them many of the thunder-weapons the Raw Men use. Doubtless you have heard of those weapons.”

“I have,” White Crow said, keeping his tone and expression neutral with better self-control than Northwind had expected from a hill-man. Certainly his retinue lacked his restraint; eagerness was evident on their faces.

“The thunder-weapons I could sell to you, if they interest you.”

“That could be done, for the right price.” The chieftain kept his tone neutral still, but his breathing had become ever so slightly faster. Not something that many men would notice, but Northwind had learned his craft in Tjibarr itself. White Crow might have more self-control than rumour attributed to highlanders, but he lacked the sophistication of one shaped by the politics of the Endless Dance.

“The price is only part of what I require from you, before I will sell you these weapons,” Northwind said. He made his tone as overbearing as he could manage. He only wished that he could speak Wadang more fluently, to choose the most arrogant words to suit his tone. “I have a further condition.”

“Name it.”

“The thunder-weapons must be used on the Yadji. Them alone. Strike them with all the prowess that has made your previous deeds so widely renowned. Raid the Yadji with these weapons, and not anyone else. That is what I require of you, in addition to the price we agree for me to have my couriers bring the weapons to you.”

White Crow regarded him with narrow eyes; a long, silent glare that made Northwind wonder for a moment if he had pressed the arrogance too far. At length, the chieftain said, “This may be something I could accept, if the price is fair.”

“Then let us talk us consider prices,” Northwind said. He settled down into a bargaining session where his biggest challenge was ensuring that he haggled hard enough to prevent the highland chieftain becoming suspicious. For the truth was that while Northwind could bring back some sweet peppers as a small recompense for the price of the muskets, he cared naught if he brought back nothing.

This will work, Northwind decided. His façade of arrogance, and his blatant demands, would have the desired effect. White Crow would fear loss of his prestige amongst his own people if he held to such an agreement. The chieftain would surely make some raids on Gutjanal or Yigutji using the muskets, to prove to his own people that he was not a puppet of the lowlanders.

In turn, such raids would increase suspicion between Gutjanal and Yigutji, each of whom would blame the other. They would accuse the other of smuggling weapons, and mistrust would fester. Not enough to fight each other, hopefully; both kingdoms had more fear of the Yadji and their foreign Inglidj backers. But enough tension to keep the two kingdoms more wary of each other than of Tjibarr.

Better still, if anyone in the eastern kingdoms figured out that someone from Tjibarr had smuggled the muskets, and if they somehow persuaded the highlanders to describe the smuggler, why, they would find only a description that matched a known agent of the Whites. The blame would fall there. Or even if they realised that the smuggler had been someone in disguise, they would not blame the Azures, the faction which had been most staunchly against the proposal to smuggle weapons to the hill-men.

And even if by some chance White Crow held to his agreement and only raided the Yadji, well, even that would help when war came with the Regency. With this blow, the Azures cannot lose.

* * *

10th Year of Regent Gunya Yadji / 19 September 1646

Baringup [Ravenswood, Victoria]

Durigal [Land of the Five Directions]

A dog sat motionless in front of Prince Ruprecht. Rather an impressive dog, he thought. Sturdy and compact, its muscular frame radiated an aura of dextrous strength. It had pricked ears set far apart, with a broad head that flattened between its dark, alert eyes. Its shoulders were compact but well-muscled, with straight, strong legs. Its fur appeared rust-red on first impression, but when he looked more closely he saw that its coat was a mixture of darker-red and white hairs.

The dog remained perfectly still as Ruprecht conducted its inspection. Its eyes followed him, but its head and body did not move.

“Discipline, by God!” Ruprecht said. Proper discipline. Rare enough in men, and almost unheard of in animals.

The Yadji handler barked a word in his own language, one that Ruprecht did not recognise. The dog stood and then adopted a crouching posture, keeping its head and shoulders lowered and moving forward slowly as if it was slinking.

“This is how the dogs herd noroons [emus]?”

The handler shook his head. “Yes. No dogs or men can do it better.”

Having seen noroons in a field, Ruprecht could only agree. The big flightless birds made good eating, but were devilishly hard to herd. They ran on their own rather than together, could move at more than twice the speed of a man, and change or reverse direction without slowing down. The birds made moving sheep or cattle appear effortless by comparison.

A well-trained, adept herding dog like this one would be invaluable to farmers. But even more pleasing to Ruprecht. Which was, no doubt, why the handler had brought it here. He suspected that every man in the Yadji empire knew of his fondness for his boxing gupa [kangaroo], Sport. The handler would be seeking similar reward.

And, perhaps, the dog had been sent here as a distraction by the Yadji nobles. Some of them knew of his growing dissatisfaction with being trapped here while the Yadji emperor adhered to a pointless truce with his native enemies.

“What is the dog called?” the prince asked.

The handler gave a name, another Yadji word which Ruprecht did not understand.

“Will he answer to another name?”

“In time, my prince. And he answers to commands in word or gesture.”

“Splendid. I prefer a name I know. I will call him... Boye.”

The Yadji handler bowed. “I can assist you with training him to obey you.”

“Of course,” Ruprecht said, though his thoughts was elsewhere. Boye had been meant to keep his mind diverted, he was sure of it. “I will send for you again soon.”

The handler showed himself to be more alert than most of his countrymen, for he bowed again and withdrew.

“Well, Boye, what am I to do with you?” Ruprecht asked, switching to German. No-one was near enough to overhear, but he used that language anyway. Too many of the Yadji understood English nowadays.

The dog looked up at him. Incapable of giving an answer, perhaps. But alert all the same.

“Your people want me to spend the next two years waiting. No gold, no glory, no action. Even if the war restarts after that, I have nine hundred soldiers who want war and prizes, not inaction in a kingdom of savages. Should I put up with that?”

The dog looked at him, and gave a slight whine. So Boye understood the question, even if he could not answer it.

“I agree, Boye. This is not right. I have to take my soldiers somewhere. But where?”

Ruprecht waited, but Boye did not offer any opinion.

“Only two choices. Well, three, but I’m not going to go back home yet. One choice is the island across the waves, which these savages call the Cider Isle. A place of gold and war, by all accounts. The Company is sponsoring one kingdom of savages to fight the other. Plenty of opportunities there, for crack cavalry, good Christian soldiers, who have the discipline to kill savages.”

The dog whined and dropped its head.

“Maybe you’re right,” Ruprecht said. “Plenty of gold, but not many Company ships to take the men across, and I wouldn’t trust these native ships with your neck, never mind mine. And I doubt these savages speak the Yadji language. Learning one heathen tongue has been enough work; I don’t want to have to start all that again. Or waste the rank I’ve built up with the Yadji.”

Boye kept his head down, but made no other comment.

“One other choice, I think. Far to the east of the Yadji realm, their subjects are growing restless, I hear. Gurnowarl, they’re called, or something like that. A display of good horseflesh will convince them to stay under the thumb. And if they rebel while we’re over there, then not even these Yadji savages can stop us looting while we’re putting them down.”

Ruprecht looked down, but Boye remained stolidly silent. “Better yet, after that, there’s the highlands. Home to barbarians so bad that even these savages call them savages. Raids have picked up. Bringing the highlanders to heel, now that would be something worth accomplishing.”

“And I’m sure I could persuade a few hundred of their infantry to accompany me.” Foot could not stand up to proper cavalry, but they made a useful anchor in battle all the same. And he would need to garrison the towns he conquered. “Less gold, maybe, but more glory. The Yadji Emperor should give me a golden handshake for quelling the highland savages. More gold than anything in the Cider Isle, I hope.”

“Or perhaps not. Trust not to gratitude of princes, it’s said. What do you think, Boye?”

Ruprecht held up a hand. Boye looked up at him, and barked twice.

“Yes, I think you have the right of it,” Ruprecht said. “The highlands call.”

* * *

Azure Day, Cycle of the Sun, 408th Year of Harmony (3.23.408) / 12 December 1647

Hanuabada, Rainy Island [Hanuabada (“Big Village”), Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea]

Clouds built up on the western horizon, but so far no rain fell. Fortunate. Yuma Tjula was still not entirely familiar with the rhythms of these northerly lands, despite living here for five years, but it had not taken him long to learn the time of the wet season. The time of so much rain as to be unnatural. And that season held true as much on this rainy island as it did in his new home across the Coral Strait in Wujal [Cooktown, Queensland].

With the air still clear, picking out the arriving ships was easy. Five lakatoi, as the locals called them. The vessels were really multi-hulled canoes rather than properly-made ships, built and rebuilt after each voyage. But they were still large enough to carry considerable cargo. Some of the locals were wading out into the water to greet the arriving lakatoi.

Yuma turned his gaze away from the sea and ships, to face the man standing beside him on the sand. Werringi the Bold. A man from a rival bloodline, that now worked in cooperation with his own. Between them, they had forged the trading association, the nuttana, that offered new hope where the Island had failed. Six bloodlines had now joined the association, but Werringi and Yuma remained the heart of the nuttana. If they supported a venture, it would be accepted. If they opposed a venture, it would be rejected.

“How far have those ships sailed?” Werringi asked.

“Across the great bay [Gulf of Papua], no more. Not a bold voyage” – both men shared a grin – “but these Motuans are a trading people, all the same.”

“Clay pots for crops and timber.” Werringi nodded. “Odd to think of clay as an item worth trading. But then where there is need, there is commerce.”

“Or where there is greed,” Yuma said. He gestured, and they started walking along the sand toward the town, with its big houses on stilts. “Most of their crops are worthless. Rabia [sago] is bland and bulky. Too far to sail for food, too.”

“Useful if famine threatens closer to home.”

“Perhaps. The headhunters who farm it seem to have plenty to spare, with how much they give to these pot-makers. But the tohu [sugar cane], this is what matters.” Yuma smacked his lips.

“So I’ve known, since I first found it in Batabya [Batavia],” Werringi said dryly. “But knowing that and getting the crops and workers to make use of it are two different paths.”

“Both can be found here on the Rain Island.”

“The tohu, yes. The same, or nearly. But the workers? These headhunters know not metal. Or much of anything else. Can they boil it properly and gravel [crystallise] it as the Nedlandj do in Batabya?”

“Not that I have seen. But they can grow it. That is enough to begin,” Yuma said. “Even the taste of the sweet juice is reward enough. You can see for yourself soon.”

Sure enough, the curly-haired locals brought several long stalks of tohu: thick, jointed, and coloured a dull red-brown. One of them demonstrated for Werringi how to cut off a joint of the stalk and then cut it open to extract the pith in the centre, and chew it.

Werringi used his own knife to cut off another joint of the stalk, and then put it in his mouth. After a brief moment’s chewing, he grinned. He did not speak, not with his mouth full of tohu pith and juice, but then he did not need any words.

Yuma said, “We must invite some of these Motuans, or their headhunting friends, back to Wujal. To bring this tohu with them, and grow it there.”

As Yuma had expected, Werringi shook his head in vigorous agreement.

* * *

The highlands of Aururia: a thinly-populated region inhabited by peoples who seemed to take in warfare with their mother’s milk. Raiding and plundering was a way of life for them; in a land where resources were scarce, many people found it more useful to take what others had produced rather than develop their own. The highlanders happily fought each other, but they would gleefully raid into the lowlands. The Five Rivers had been their prize target for hundreds of years, but in the last couple of centuries they had become equally fond of paying armed visits to Yadji lands.

Counter-invasion of the highlands proved difficult, mostly because there was little worth raiding. The highlands were lands of scattered farms, filled by people who knew how to cache food to keep it secure from both the natural ravages of flood and fire and more human-induced depredations. The handful of villages and towns were mostly places where people came temporarily for markets or celebrations; burning them or looting them would barely hinder the hill-men’s capability to resist.

Highlanders would rarely fight stand-up battles without being forced into them, and they were adept at using their knowledge of the local countryside to evade pursuit. Invading forces were plagued both by the lack of accessible enemies to fight, and the difficulty in obtaining sufficient supplies. Some commanders would withdrew in frustration, while more successful ones would demand some level of tribute which was enough for them to proclaim victory before they discreetly withdrew, too.

Prince Rupert, Duke of Cumberland, knew little of this long history. What information he had gathered about the highlands told him of their success at raiding, but little about the extreme logistical difficulty of suppressing them. Rupert believed, with some grounds, that his cavalry would allow him to chase down hill-men who tried to flee on foot. Quite how he would feed those same cavalry was a question he did not consider in as much detail.

Prince Rupert had also expected that the Yadji rulers would provide only lukewarm support for his expedition. This expectation was only testament to his misunderstanding of a people he still viewed as savages. The Regent Gunya Yadji and his leading generals were enthusiastic in commending “Prince Roo Predj” for his valour in proposing to quell the highland savages.

For the Yadji, Rupert’s departure was a three-fold blessing. Firstly, it would let him indulge his plundering instincts in territory which the Yadji cared nothing about. Secondly, it gave them the opportunity to send some inexperienced infantry with him, so that they could gain military experience before the truce with Tjibarr expired. Thirdly and most importantly, it removed the risk that his growing boredom could lead him to break that same truce.

So Prince Rupert found himself leading nine hundred European cavalry and fifteen hundred Yadji infantry. The horsemen were all veterans of the late European war and the first fighting in Prince Rupert’s War. The infantry were mostly newly-trained troops, with a smattering of veterans distributed throughout them in Yadji style, to teach them and stiffen their resolve.

He had two objectives in mind. Firstly, to make a grand march along the Yadji royal road to dismay the rebellious Kurnawal into submission. Secondly, to impose a string of stunning victories on the highlanders and quell them into submission, too.

Rupert’s first objective was a success. Horses were unknown in the eastern regions of the Yadji realm, and the grand procession of cavalry and infantry alarmed the Kurnawal, who were indeed growing rebellious, a decade and a half after the last time the Yadji had suppressed a rebellion.

Rupert’s second objective... was not such a success.

The high country taught the German prince, as it had taught so many before him, that it was one thing to build an army which the hill-men could not defeat in battle, but quite another thing to build an army which could eat trees and grass. Even for the four-legged part of his army that could eat grass, the rigours of daily marches seldom left the horses with enough time to replenish their energy by grazing at night. And strangely enough, their highlander hosts had thoughtlessly neglected to provide fodder for their equine visitors to replenish their strength.

Rupert’s cavalry could indeed do as he had expected, and run down any highlanders caught in the open. Which would have been more helpful if the highlands had more open ground to work with. Foot soldiers, he found out, could outrun horses in a place where the best roads were only muddy tracks, and when in most areas the hill-men did not have far to flee before they reached the sanctuary of trees. Where ambushes with archers or sometimes muskets were an ever-present threat, his cavalry could proceed only cautiously through forest, which gave the hill-men plenty of time to escape.

The bigger challenge was, of course, food. The prince had his soldiers burn the first couple of towns they occupied, but that did not bring the highlanders out to battle. He occupied the third town he found, but that only worked until the food ran out and most of the inhabitants vanished into the night.

The only way the invading army could survive in the highlands was to keep moving, squeezing what supplies they could from the scattered highland farms before their inhabitants hid their food and fled. This was an army continually on the march, unable to camp in one location for more than a few days. Even maintaining that kind of campaign would have been impossible without occasional resupply sent by dog-travois caravans [2] from the Yadji realm.

The hill-men fought their own style of campaign against the invading forces. They preferred to raid at night, or ambush any scouts or screening forces. Prince Rupert soon learned to be thankful for the presence of Yadji infantry, for without them defending camps at night would have been almost impossible. The highlanders rarely concentrated their forces, both to avoid risking their too-few numbers and to keep from exhausting their hidden supply caches.

By halfway through the first summer, Rupert’s army had settled into a routine. March for a couple of days, then set up a camp with some timber fortifications where his infantry could provide a secure base. His cavalry would spend several days sweeping the surrounding countryside, trying to capture any highland raiders they found. If that failed – as it usually did – he would march on for a couple of days and repeat the pattern.

With the first snows threatening in the autumn in 1647, Prince Rupert withdrew to Elligal [Orbost, Victoria] to wait out the winter. He took up the habit of painting during that winter, using some of the spectacular colours which the Yadji made. Two of those paintings would survive into the modern era. Gunawan in Flood showed a broad view of the River Gunawan [Snowy River] in springtime flood, with his beloved Boye crouching in the foreground. The Great Executioner showed a Yadji death warrior in full battle garb.

In the second summer of the truce, Prince Rupert brought his forces back into the highlands. Little had changed from the first summer. The hill-men were even more cautious to avoid open battle. The largest conflict which he could proclaim a victory involved less than one hundred highlander casualties, although this death toll was in fact more severe for the manpower-deprived highlanders than Rupert realised.

As the summer progressed, engagements became even fewer. Rupert found that his visions of glory and gold were fading in the endless pursuit through the highlands. His frustration reached the point where he was prepared to listen to his native allies, who advised him to open negotiations with the highlanders before summer was over. He duly sent out emissaries, who reported that the highland chieftains were prepared to discuss terms for a truce.

Despite the galling truth that he would have little to show for two years of warfare, Rupert negotiated a truce with the highlanders. The terms were simple: for three years, the Yadji would not return to the highlands, nor would the hill-men raid into Yadji lands. The highlanders provided a gift of a truly copious amount of sweet peppers to seal the truce.

In a sign that he had learned a little basic diplomacy, Rupert responded by giving gifts of his own to the highlanders: a horse for each of the five greatest chieftains. These were given from among the stock of spare horses whose original riders had fallen in battle. Rupert took the precaution of choosing five geldings, as he had no wish to allow the hill-men to obtain breeding stock.

When he returned to Elligal, Prince Rupert declared his great victory over the hill-men. A victory that would not last past the next raiding season, for the highlanders had never been ones to treat truces as binding if they sensed weakness. The only real thing which Rupert gained from his highland endeavours was a taste for sweet peppers which would last for the rest of his life. From that time on, he regarded almost all food as too bland to bother with unless it had been properly flavoured with sweet peppers.

From Elligal, Prince Rupert quickly led his forces back west, to the heartland of the Yadji realm. For the two-year truce with the Five Rivers kingdoms was nearing its end, and he did not wish to be left neglected on the frontier when warfare resumed.

* * *

[1] “Make an air-clay inscription” is a Gunnagal metaphor which is roughly equivalent to “make a mental note”.

[2] The Yadji do, in fact, have wheeled vehicles, but they learned a long time ago that with the usual state of muddy tracks in the highlands, the older ways of travois were better.

* * *

Thoughts?

Nice update Jared.

Thanks!

On a broader note, this instalment was the second-last to show the main part of the Proxy Wars (Prince Rupert's War / Bidwadjari's War / The Great Unpleasantness).

There will be one more post to wrap up Prince Rupert's War. The post after that will cover the fate of Daluming (those of headkeeper fame) and the changes that are happening in Aotearoa. After that, the action will skip forward to approximately 1660.

So now we know the origin of the Nuttana people, or at least part of the origin.

Are the Proxy Wars going to wind down after Prince Rupert's War? It would seem that the Europeans would still have plenty of unfulfilled goals, and plenty of Aururians willing to help them for a price.

Are the Proxy Wars going to wind down after Prince Rupert's War? It would seem that the Europeans would still have plenty of unfulfilled goals, and plenty of Aururians willing to help them for a price.

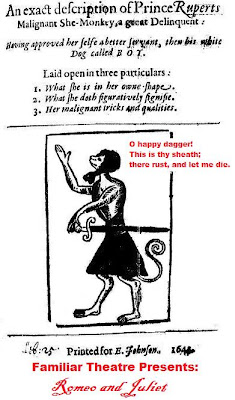

OMG I love this TL's version of Boye, I can't wait to see what the Puritans think of him. Will the Prince Rupert of this TL acquire another pet to replace his lascivious she-monkey of OTL

A female quoll perhaps?

A quoll who rides on his shoulder, whispering secrets and devilry into his ear?

Ruprecht learned some humbleness in his belief of military superiority, and provided TTL with some good paintings.

That he certainly did. The Ruprecht of OTL learned to curb his impetuousity a bit (though that took him quite a while). I don't know whether he was capable of learning that much faster or not, but he's been given his first lesson.

So now we know the origin of the Nuttana people, or at least part of the origin.

It's mostly been laid out. A core of Nangu exiles from the Island, lots of Kiyungu labourers. There will be others who join them, voluntarily or involuntarily, such as a few Papuans/Melanesians and Maori.

And the fact that modern writers (as shown in the last interlude) refer to their homeland as the Tohu Coast (sugar coast) is also a slight hint as to one of the main ways the Nuttana make a living.

Are the Proxy Wars going to wind down after Prince Rupert's War? It would seem that the Europeans would still have plenty of unfulfilled goals, and plenty of Aururians willing to help them for a price.

The Proxy Wars will last for decades. But that's a catch-all term for any fighting in Aururia (and maybe Aotearoa) that has some degree of European backing. Europeans of the time tend to see all of these wars as being their native pawns fighting each other because of European instigation. The truth is of course more complex, particularly with regard to the Five Rivers versus the Yadji.

What is winding down is basically Prince Rupert's War itself. The Yadji are devastated by the typhus epidemic, and Tjibarr isn't doing a great deal better. Prince Rupert's War will basically only last until the Yadji Regent decides he's won enough (or lost enough).

Tjibarr has no real interest in continuing the war. Indeed, while it's hard to generalise about what the people of Tjibarr want - since getting any three of them to agree about it is difficult enough - they don't really want to be involved in any war. At the moment, their dominant foreign policy objective is to make the other two Five Rivers kingdoms into subordinate powers and allies against a Yadji resurgence, not to create new wars.

Some of the other wars will last longer. The little war amongst the Mutjing (Eyre Peninsula) has already been mentioned. Tasmania is fighting itself, as it so often does. But once Prince Rupert's War is wrapped up, the main fighting will be amongst the smaller nations of the eastern seaboard.

And possibly some English-backed uprisings amongst the Atjuntja, although I don't really intend to explore too much about the Atjuntja until a few posts down the track. (Their history tends to run separately from the more easterly peoples, so it makes it easier just to write separate posts about them).

Threadmarks

View all 71 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Lands of Red and Gold #122: A Man Of Vision Lands of Red and Gold #123: What Becomes Of Dominion Lands of Red and Gold Interlude #5.5: Interview With The Eʃquire Lands of Red and Gold is now published! Aururian Fire Management Lands of Red and Gold Interlude #15: Into Darkness Contest - Guess The Character Lands of Red and Gold Interlude #16: Minutes Take Hours

Share: