From a letter by a sixteenth-century Spanish missionary.

Everything is upside-down in the West Indies.

It is European custom for the well-bred to read and write, the lesser-born to do neither. But here in Mexico, it is strictly the burghers, the merchants and the peddlers, who write. Their grandees and magnates can read and write as well as any merchant, but they will not be caught dead with a scroll in their hand. They think of their own alphabet as a thing to be ashamed of, as a sign of such personal dullness and slow-wittedness that mere mnemonics must be resorted to. How strange they are!

The Indian nobles read paintings instead. This is no misspelling; they read their paintings.

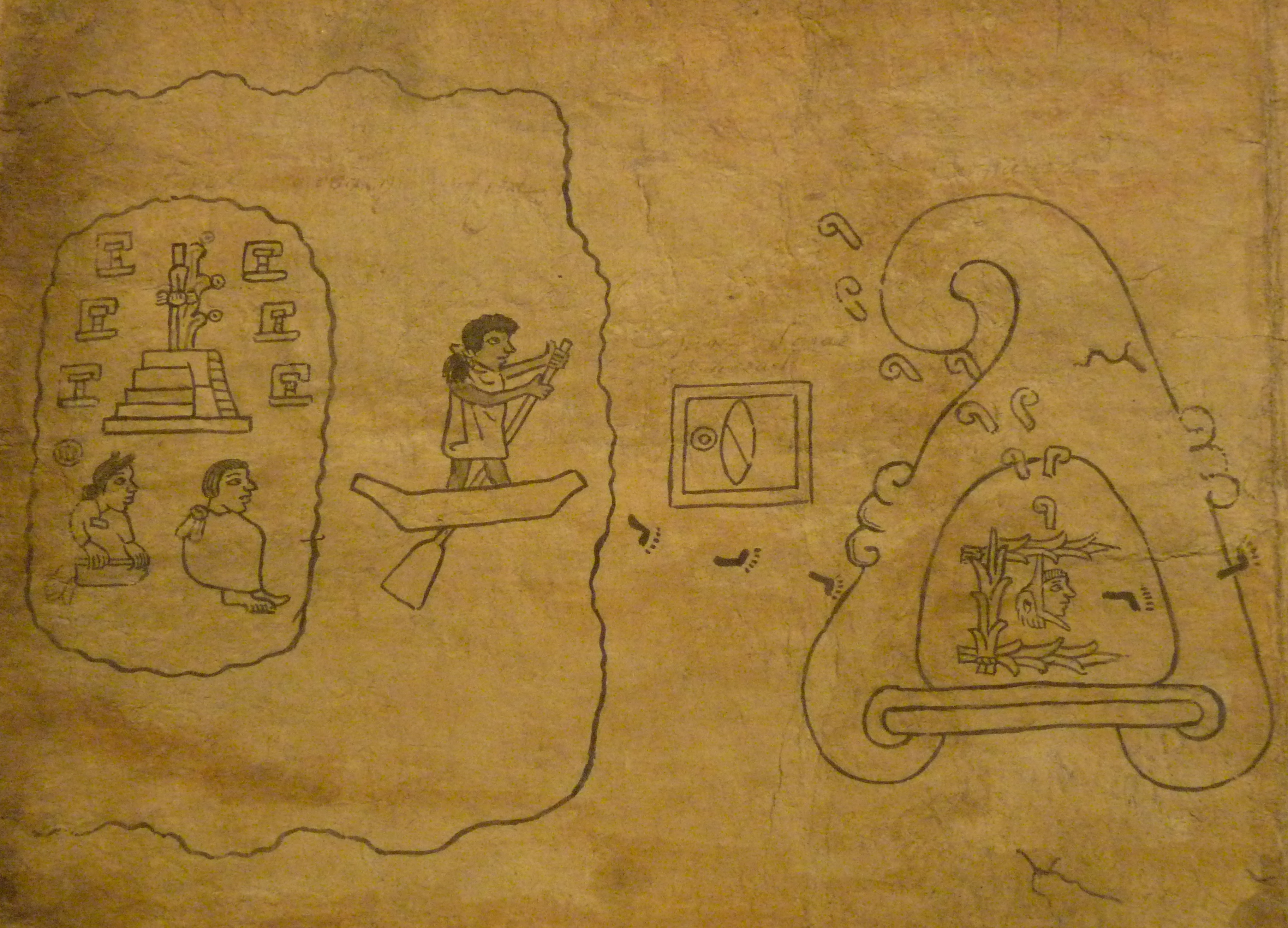

I give you my own sketch of one of their paintings below, said to be the illustration of a little-known poem by a man of Mexico.

I have asked ten Indian nobles to interpret this painting. Three each were from Mexico and Chontalpa, two from Haiti, one from Michoacán, and the last from Nicaragua. Two of the Chontal Indians knew the Mexican language; the other five did not.

They have all given me an almost identical interpretation:

I, a ruler who remembers rulers, the singer, with sad flower tears set my song in order, remembering the princes who lie shattered, who lie enslaved in the place where all are shorn, who were lords, who were kings on earth, who lie as dried plumes, who lie shattered like jades. If only this could have been before these princes' eyes; if only they could have seen what is now seen on earth, this, this knowledge of the Ever Present, the Ever Near.

The Indians say:

- Because the man on the bottom left faces the viewer, this is “I.”

- From the attire of this man and the mat on which he stands, “I” must be a ruler.

- “I” is crying tears that turn to flowers. His expression is that of grief.

- “I” is singing, as seen by the speech scroll that issues from “I”’s mouth like a tattooed tongue. “I” is handling and arranging these scrolls – these songs.

- The upper-right box connects to “I”’s head. This means that “I” is thinking these things.

- The black footsteps in the box leading to “I”’s head means that “I” is not only thinking, but remembering. If the footsteps led away from the head, he would be predicting.

- There are black footsteps leading to the lower half of the box, meaning that the upper half is in the relative past.

- The upper half portrays three kings on a grassy vale. Because they are not numbered as three, the meaning is simply “kings” and not specifically “three kings.”

- The lower half has two boxes. One shows these lords torn apart and tied with thin lines to broken shards of jade. The other shows them enslaved by a multitude of shorn men and tied with thin lines to desiccated feathers. These thin lines signify a comparison between dissimilar elements.

- Because these boxes are under the earth, they must be the land of the dead.

- The lower right box’s position relative to the other elements of the painting means that it signifies a supposition or a wish. Because the box points toward “I,” it is “I” who is wishing these things.

- The heads of the lords portrayed in the box above are in this box. The rest of the images in the box are enclosed in a bracket issuing from the eyes of each of the lords; “I” thus wishes that these lords would see something.

- Two brackets that point to the torments of the dead lords above. “I” thus wishes that the lords of the earth would see “this,” their future fate in the underworld. The doubling of the brackets is emphasis. There is also a stylized eye signifying “knowledge.” “I” wishes that the lords of the earth would see a knowledge of something.

- The final bracket issues from the eye and encloses the characters for “night” and “wind.” To the Indians, the Night and the Wind are a name of God, because God is said to be invisible like night and intangible like wind. Another of their names for God is "Ever Present, Ever Near."

All the Indian lords knew this, even without knowing the Mexican language.

In the West Indies, every fresco and portrait is a book.

Privately, and when haste is called for, even the lords write in the alphabet. The alphabet of Mexico has sixty letters of lines and squares, shared throughout the West Indies. The Indians say that this alphabet was invented by a rich merchant-king in the Maya city of Xicalango, who simplified the hundreds of characters of the Maya so his merchants could know how much of what to sell, and when; this seems to me to be the case as well. I will expound on my reasoning in a later letter.

Each character in their alphabet stands for a vowel and a preceding consonant. When a syllable ends in a consonant, the letter starting with that additional final consonant and with the vowel “i” is added at the bottom of the main letter. The same principle applies for a long vowel. They write in our direction, and not the Moors’.

I have written a part of the Lord’s Prayer in their alphabet below, as you asked.

Yet I cannot help but fear that the lords of Mexico will only laugh at us if we were to write the Holy Bible in their alphabet; it would be as if we were to make a new Bible of our own, changing each noble and sanctified word with childishness and crude vulgarities. Only with portraits and pictures will the great men believe.

* * *

I apologize for the poor quality of my pencil sketches.

Postclassic Mesoamerican writing experienced two opposing movements.

The first was the movement towards a more pictographic system, with less abstraction and less relation to the spoken language. The Aztecs and their neighbors “wrote” in standardized pictures with no direct relation to the spoken word. Many historians refer to such picture-writing as an example of an “iconic semasiographic system,” a category which today includes road signs and cleaning instructions.

(“Iconic” refers to the pictographic nature of such systems in opposition to arbitrary semasiographic systems, like modern mathematical formulas and musical notations. “Semasiographic,” from Greek

sēmainein “signify,” means that the system expresses the writer’s meaning directly without the intermediary of spoken language.)

This was a useful strategy, and Mesoamerican resorted to iconic systems for much the same reasons we do. Just as standardized road signs allow a Korean to drive in Germany without knowing any German,

Most of the images on the pages of the Matrícula [Aztec book of tax registers]… make little direct reference to a specific language. This was a conscious—indeed essential—communication strategy. The Matrícula was created to show the tribute brought to Tenochtitlan by people from throughout the Aztec empire, many of who spoke languages very different from Nahuatl (the language spoken by most people in Central Mexico). Because phonetic writing systems require translation in multilingual contexts, it is often more effective to use non-phonetic strategies for writing and documentation. Most of the information recorded on the pages of the Matrícula could be understood by speakers of Mixtec, Otomi, Zapotec, Maya, and even Spanish and English speakers today, five centuries later.

(

Source)

To give you a very simple example, here’s the first page of the

Codex Boturini, an Aztec codex from the 1530s.

It’s difficult to tell what’s going on from the picture alone, just as no Aztec could have understood our road signs without training. But a Mesoamerican could tell:

- On the island to the left, the man and the woman are dressed and sitting in what is a stereotypically Aztec manner. This suggests that these people represent the Aztecs as a nation.

- A shield is connected to the Aztec woman. Her name must have something to do with a Shield.

- The island has houses and a small pyramid; the Aztecs on the island are thus living in a city. There is a stylized image of water and reed on top of the pyramid, which must represent the name of the island.

- A man is paddling across the lake on a canoe. This symbolizes the action of crossing the lake.

- Footsteps lead from the lakeshore to a curved hill. Footsteps, of course, symbolize movement.

- A small human head wearing a hummingbird helmet is inside the hill. Speech scrolls are issuing from the head. The head is enclosed in a reed shelter.

- Footsteps lead away from the hill and off the page.

- The cartouche in the middle has a flint stone next to a single circle.

Without knowing any Nahuatl, Mesoamericans could reasonably “translate” this picture as:

The Aztecs once lived in the Place of Water and Reed, a small island city in the middle of a lake. They were led by a certain Shield Woman. In the year 1 Flint, they crossed the lake and came to the Curved Hill. There, they encountered or built a small reed temple for a Hummingbird God, who gave them orders, presumably (based on the footstep leaving the page) to go further on. So the Aztecs left the Curved Hill.

This is quite similar to the actual story:

The Aztecs once lived in Aztlān [represented with a water and reed glyph], a community in an island lake. In the year 1064 A.D. [1 Flint in the Aztec calendar], the god Huītzilōpōchtli [Nahuatl for “Left Foot like a Hummingbird”] told the Aztecs to migrate. They crossed the lake and came to Cōlhuahcān [cf. cōlihui, the Nahuatl verb for “to curve”]. They were accompanied by the female spirit Chimalmā [Nahuatl for “Shield Hand”]. In Cōlhuahcān, they constructed a simple reed temple for Huītzilōpōchtli. The god then ordered them to go further on, and so the Aztecs left Cōlhuahcān.

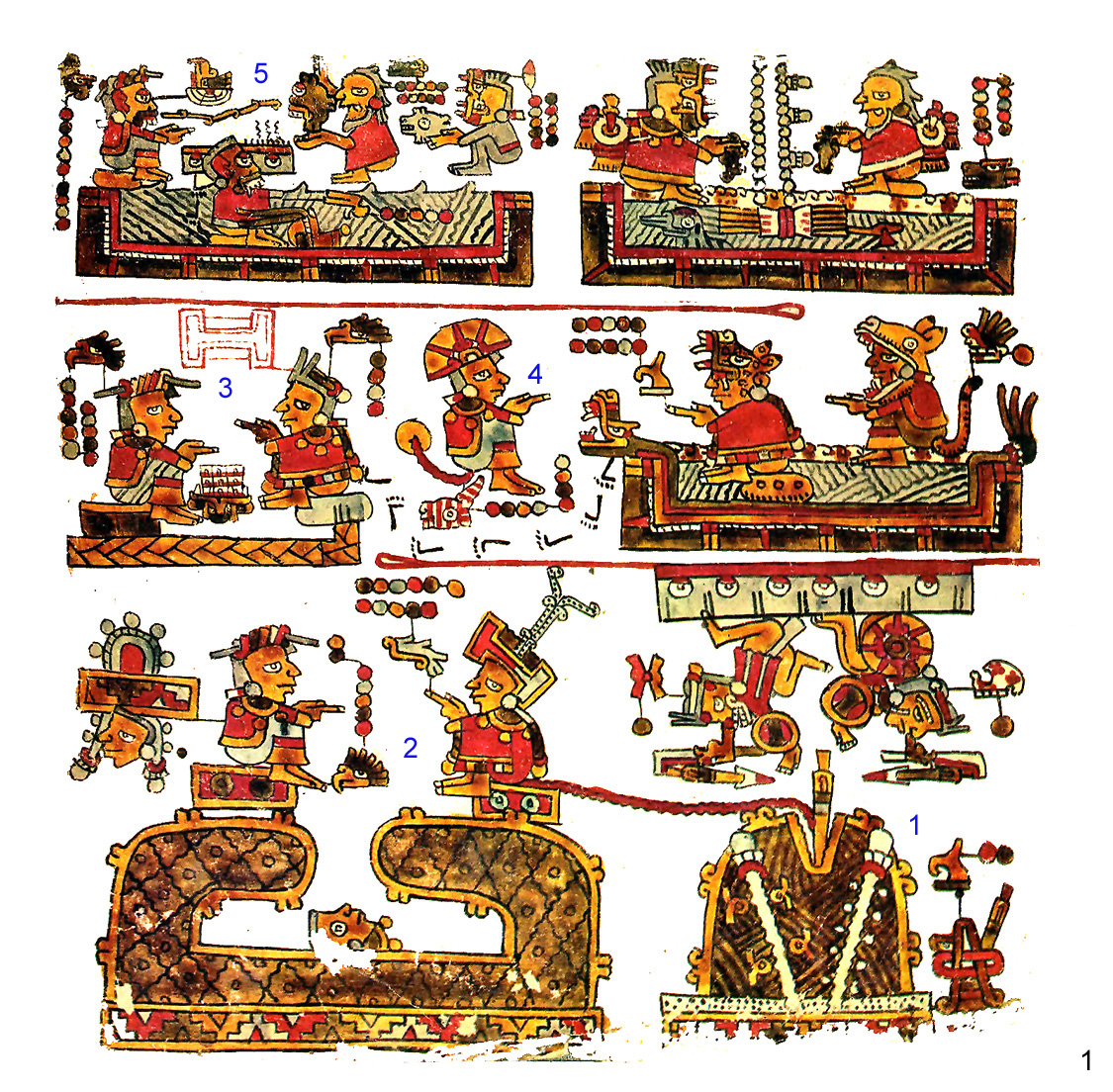

A trained Mesoamericanist can accurately interpret far more complex paintings, like this page of the

Codex Selden, a Mixtec book of history about the dynasty of Añute.

At the same time, Late Postclassic Mesoamerica showed tendencies of moving towards a more phonetic system that represented the spoken language directly. All Mesoamerican writing systems lay on a spectrum between “full semasiography,” with no linguistic elements whatsoever, and “full phonetic representation,” totally dependent on the spoken language. Neither extreme was ever reached.

As mentioned, Aztec picture-writing was basically semasiographic. Yet proper nouns were regularly written with the aid of a series of phonetic glyphs: pictures that represented the first

syllable of their word. In one Aztec text, for instance, the name “[Mo]tēuczōma” (Moctezuma) is written not semasiographically with a painting of an angry lord (the famous name comes from

tēuctli “lord” and

zōma “irritate”) but with a stone (

tetl in Nahuatl), a bowl (

comitl), a lump of clay (probably from

tzohcuiltic, “dirty”) and a hand (

māitl): Te-Co-Tzo-Mā.

However, Aztec syllabic writing was still limited in both use – they were reserved almost exclusively for proper nouns, where iconography would be unacceptably ambiguous – and versatility. One telling fact is that Spanish glosses of Aztec codices suggest that Aztec scribes had not yet invented glyphs for the syllables

ti and

qui. This is despite the fact that

ti- was the Nahuatl morpheme for the pronoun “we” and

qui- the morpheme for “him; her; it.”

More famous is the Maya script. Unlike the Aztec or Mixtec systems, Maya glyphs are clearly distinguishable from iconography and capable of directly transcribing anything said in the Maya language. This of course means that written Maya cannot be understood by a layman, not even to the limited degree that a modern American layman can interpret Aztec iconography.

There is some evidence to suggest that Mesoamericans in both Central Mexico and Maya country were using more innovative phonetic symbols in larger quantities. Perhaps Cortés interrupted the development of a full Mesoamerican syllabary.

To sum up, there are two opposing tendencies in Mesoamerican writing. One favored a pictographic and iconographic system detached from the spoken word, leaving more to ambiguity but allowing easy understanding by speakers of different languages. Another favored a system that transcribed the spoken language directly, eliminating ambiguity beyond what was normally present in speech but impeding cross-cultural understanding.

A syllabary would certainly be more useful for commercial purposes, and commerce has grown significantly ITTL. But so has cross-cultural contact, where an iconographic system would be immensely valuable.

My solution is a sort of literary diglossia, a little like the situation in Early Modern Korea where Classical Chinese was the writing of public discourse and the

Han’gŭl script the writing of the private and feminine spheres. The nobility of TTL’s New World now has an even more formalized iconographic system that is much less ambiguous than what we had OTL – I'm not aware of anything like using footprints to mark temporal relations within a picture IOTL. But as beautiful and useful as this painting-writing is, it’s inefficient for more practical purposes, and so we have a syllabary, one that I made by simplifying the OTL Maya syllabary until they were nothing but squares and lines, a little like the abstraction the Chinese script or our own alphabet underwent.

There are some fantastic resources out there about Mesoamerican writing systems: