Prologue: The French In a Whole New World

Prologue: The French In a Whole New World

From top to bottom, the colonization of the Americas impacted almost every single country in western Europe. France was no exception to this rule. Resources from the New World caused France to eventually become one of the richest and most powerful nations in the world. They were not the first country, however, to discover this new landmass and identify it as such. Several other explorers from different European countries beat them to it. Italian explorer and navigator Christopher Columbus, under the Spanish Crown, made four voyages across the Atlantic Ocean to the Americas (namely the Caribbean, Central America, and South America). During his first voyage in 1492, he departed Spain with three ships: the Niña, Pinta, and Santa María. He made his initial landing on the island of San Salvador where encountered the indigenous Lucayan, Taíno, and Arawaks. He came in search of gold and other precious metals and when he saw their gold earrings, he demanded that they guide him to the source, even if it meant unfortunately imprisoning, torturing, or even killing the Arawaks. In 1493, on his second voyage, Columbus set up the first European colony in the Western Hemisphere on the island of Hispaniola and named it Santo Domingo. This set the stage for European policy in the region for centuries to come. Still, even after he had made two additional return trips to the region, he died in 1506 believing he had reached Asia, as it was assumed at the time that there was no landmass between Europe and Asia.

It was not until Amerigo Vespucci (sponsored by the Portuguese crown) during his 1501-1502 voyage that it was verified that this was a separate landmass from Asia and named it “the Americas.” Initially, only Portugal and Spain were involved in the exploration of the Americas. The dividing line, initially created in 1493 by Pope Alexander VI, was revised and solidified in the 1494 Tordesillas. This meant that Spain acclaimed all lands west of the meridian 370 leagues west of the Cape Verde Islands and Portugal to the east. This line, however, reserved what would become Brazil for Portugal. Of course, most countries that became Protestant, such as England and the Netherlands, or third parties such as France did not recognize said treaty. This could be observed as far back as 1497 when John Cabot, as previously mentioned, was sponsored by the English to discover the Northwest Passage to Asia and ultimately discovered Newfoundland and the surrounding areas. Nevertheless, the Spanish and Portuguese used this as an opportunity to attain wealth and power via gold, silver, and other riches and spread their Catholic Christian beliefs to the indigenous peoples (often by force). That being said, it certainly helped that Italy was too weak and disunited politically, the Netherlands too small, and England generally disinterested at the time to be much of a threat to the large-scale colonization of the Iberians who had gained large swathes of land in the western hemisphere for their colonial empires in the 1500s.

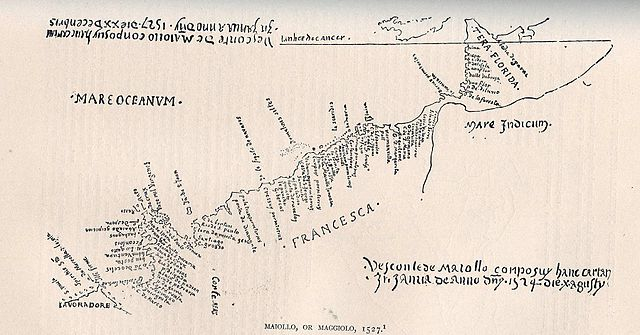

The French soon got involved in the exploration and colonization of the Americas. They initially came to the New World traveling to seek the Northwest Passage to the Pacific Ocean under the rule of French King Francis I. In 1524, he sent Italian-born explorer Giovanni da Verrazzano to explore the region between Spanish Florida and English Newfoundland as a means of finding a route to the Pacific. In March 1524, he arrived along the Atlantic Coast of North America, looping north at 33 degrees North. On his way up the coastline, he found what he thought to be a large lake but later discovered to be a bay to a much longer river. He ultimately reached as far North as Newfoundland before sailing back to France in July. Verrazzano gave the names Francesca after the King of France to the land between New Spain but his brother’s map named it Nova Gall (New France). Between 1534 and 1536, Jacque Cartier took this one step further and explored the Gulf of St. Lawrence and the St. Lawrence River (referred to as the Rivière du Canada before morphing into the Ottawa River further inland). He named the region “Canada” from the Iroquois word “Kanata” meaning village. On his third voyage in 1541, Cartier was ordered to go back to Canada to create the first French colony in the region. A fortified settlement was created that summer and was named Charlesbourg-Royal in honor of Charles II, Duke of Orleans. However, the colony was abandoned in September 1543 due to the harsh climate, disease, and Native attacks.

After that, it seemed for a while that France lost much of its will to colonize the Americas. Starting in 1517, the Protestant Reformation had swept through large swathes of northern Europe and rose from what were perceived to be systematic discrepancies and abuses on the part of the Catholic Church. This posed a major religious and political challenge to the Catholic order held over much of Europe up to that point. France was yet another battleground of the Reformation Movement. Initially tolerant of the French Protestants, this changed in 1534 after the Affair of the Placards when Francis came to view the Protestants as a threat to French stability. Protestants were deemed heretics and the persecution against them increased. The number of “heretics” tried and put to death also grew. The persecution grew further when special courts known as "La Chambre Ardente" were set up under Henry II in 1547. Despite this, the generally Cavlnist Protestants made progress in many circles, especially among the urban bourgeoisie and parts of the aristocracy and nobility. French Protestantism soon came to acquire a solid political character. Still, none of this stopped Protestants from fearing for their lives. The first Protestants to leave France sought freedom in Switzerland and the Netherlands, but this changed starting in 1555 when French vice-admiral Nicolas Durand de Villegaignon made it his mission to help Protestants find refuge from intolerance and persecution against them across the Atlantic Ocean.

Last edited: