You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Kolyma's Shadow: An Alternate Space Race

- Thread starter nixonshead

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 47 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Part IV Post#4: Restructuring Part IV Post#5: Planetary Pilgrimages Part IV Post#6: The Expendables Part IV Post#7: Coming In from the Cold Part IV Post#8: Fantastic Fiction by Brainbin Part IV Post#09: Space Wars Part IV Post#10: Handshake in Orbit Part IV Post#11: End of an EraChelomei happens to be the boss of the Party Chairman's son?

Well, the old good-old-boy network works, even in the space program.

No 'happens to be'. Chelomei specifically hired Sergei for his political connexions (although I gather Sergei was a decent rocket engineer).

No 'happens to be'. Chelomei specifically hired Sergei for his political connexions (although I gather Sergei was a decent rocket engineer).

Thanks for the correction, Dathi.

Chelomei happens to be the boss of the Party Chairman's son?

Well, the old good-old-boy network works, even in the space program.

No 'happens to be'. Chelomei specifically hired Sergei for his political connexions (although I gather Sergei was a decent rocket engineer).

Yep, ITTL and IOTL Chelomei hires Khrushchev, giving him personal access to the top of the USSR's leadership.

Whilst I wouldn't exactly classify it as an 'old-boy network', there is definitely a value to personal contacts even to this day, at least in the European space industry. This basically comes down to it being a relatively small industry with lots of collaboration between countries and companies on various projects - meaning you need to be careful about pissing someone off, because you'll probably end up working with them again at some point (something Chelomei seems to have been a little careless about).

Part I Post #9: Bang, Zoom! Straight to the Moon!

After last week's excursion into the wider world, this week we return to space for the penultimate Part I post of...

Part I Post #9: Bang, Zoom! Straight to the Moon!

As the Atlas missiles stationed at Vandenberg were being prepared for a possible launch against Moscow in January 1961, another Atlas was undergoing checks at Cape Canaveral with a more peaceful purpose in mind. This was the Atlas-Agena rocket intended for the launch of the world's first deep space probe, Pioneer. The 200 kg spacecraft had been built by the Jet Propulsion Lab as a follow on to their Explorer designs and was intended to make a flyby of the Moon on its way to an independent solar orbit. It carried a number of particle and field sensors, but the highest expectations fell upon its sophisticated camera system. This camera, it was hoped, would at last allow humanity to see what lay on the far side of the Moon. Theories ranged from something essentially identical to the nearside's geography to fanciful suggestions of valleys containing breathable atmospheres, strange Selenite plants, or even a race of advanced Moon-men. Pioneer was intended to settle these questions.

At least it would if it could get off the launch pad. The original launch date of mid-January was postponed at the last minute as the Berlin Crisis was reaching its peak. Although most analysts agreed that it would take a very paranoid Soviet radar operator to interpret the launch as a missile strike, paranoia was very much in the air, and nobody felt that it was worth taking a chance on. The mission was therefore stood down for two weeks whilst the Berlin situation stabilised, and then waited a further two weeks for the Moon to enter a favourable position, with the aim of making a flyby around the time of the New Moon so that the farside would be fully illuminated. However, although the Moon may have been ready by mid-February, it transpired that the launcher was not. The Atlas rocket's core engine failed 45 seconds into the flight, leading to the destruction of the missile by safety officials.

The run of bad luck continued, as a second rocket and spacecraft could not be made ready in time for the March opportunity, whilst the April window was plagued with high cloud cover that would restrict visual tracking of the launch. It was May before the second Pioneer attempt successfully lifted off the pad, but even then the bad luck continued as the Agena upper stage shut down prematurely, stranding Pioneer 1 in a highly-elliptical Earth orbit. The control team at Pasadena were able to operate the spacecraft for several months, validating the imaging system by photographic Earth and using the radiation sensors to explore the Outer Vernov Belts and magnetosphere, but it was hardly the achievement everyone had hoped for. This was especially true at a time when the Air Force was questioning the value of diverting launchers from the vital Keyhole spy missions to Moon probes (disparagingly referred to as "Alices" by the Pentagon brass).

As in many other arenas in the zero-sum game that was the Cold War, America's misfortune was seen as a boon to the Soviets. Mishin had been working hard on his R-6 upper stage (Blok-V) since late 1959, but it was still nominally at least 6 months away from a launch by the start of 1961. His efforts to improve this schedule were hindered by the total lack of assistance from Glushko and Chelomei for his kerolox engine. In fact Mishin was beginning to suspect deliberate sabotage by his “comrades”, perhaps relating to the June 1960 decision by Ustinov to re-allocate development of the manned space capsule from Chelomei to Mishin. Chelomei was not happy with the loss of this prestige project (even if it was intended only as a stop-gap on the way to his Raketoplans), and Mishin felt a definite itching between the shoulder-blades whenever the OKB-1 Chief Designer was in the room. This paranoia appeared be justified when Barmin informed Mishin in late 1960 that there would be a three-month delay in installing liquid oxygen tanks at Tyuratam due to the start of work on facilities for Chelomei's UR-500, a rocket which wasn't scheduled to fly for at least five more years. In this context, Mishin saw the delays being suffered by the Americans as a glimmering opportunity to trump them in a major space "first" and put himself into Khrushchev's good books, hopefully giving him the political leverage to push back against his rival Chief Designers.

To meet this push, Mishin took a savage knife to the Blok-V's development and test schedule, cutting out anything he deemed nonessential. Similarly, the Luna probe he planned to launch was cut down from an ISZ-like science station to little more than a camera attached to a radio, with an attitude control system taken off-the-shelf from the Sammit programme. This could operate either as a fly-by probe to image the farside, or as an impactor that would transmit pictures of the surface before forming the Moon’s first man-made crater. When the technicians at Miass had completed assembly of the probe and announced they were about to start end-to-end electrical tests, Mishin overruled them with a brusque "Test it on the launch pad!"

These herculean efforts meant that Mishin was able to get his uprated R-6A on the launch pad by mid-April 1961. Unlike at the Cape, conditions at Tyuratam were fine for a launch (though many suspected Mishin would have pushed ahead even in a thunderstorm), and the R-6A left the pad at the beginning of its launch window. Despite Mishin's fears that Chelomei might engineer an "accident" to scupper him, the R-6 Blok-A and Blok-B stages worked perfectly, putting the Blok-V/Luna combination into a low elliptical Earth orbit. This hurdle passed, at the appointed time the Blok-V's kerosene/oxygen engine was commanded to fire... and did nothing. The stage refused to light, and within a few hours had drained its batteries, leaving it dead in space.

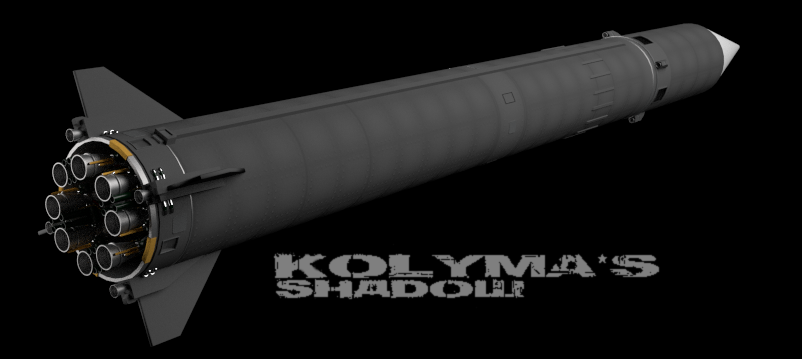

First launch of the R-6A “Luna” rocket, incorporating Mishin’s kerolox Blok-V upper stage, April 1961.

Over the next week, checks on the two other completed Blok-V's at OKB-385 revealed that both had a wiring fault in the complicated system designed to light the rocket in the zero-gravity, zero-atmosphere environment of space. The fault should have been caught at the design stage, or at least during testing, but Mishin's push to meet an arbitrary schedule had cut those tests out. The problem was corrected and the new stages shipped to Tyuratam in readiness for the next launch window in May. However, this attempt would prove even less successful than the first, as the R-6A’s Blok-B exploded in mid-air before Mishin's stage had a chance to prove itself.

Aware of the risks and unwilling to wait a further month for optimal lighting conditions for a flyby, Mishin had another Luna R-6A standing ready in reserve, and this was rushed to the pad in the following two days to carry out the impactor mission. Finally, on this third attempt, all three stages fired on cue, and the L1-A “Luna 1” probe was placed into its transfer orbit. Unfortunately, the Moon Curse held, as a guidance error meant that the transfer orbit would miss the Moon by almost 100 000 km and head directly into interplanetary space. Even the lesser distinction of launching the first Earth escape spacecraft was diminished when the thermal control systems failed to adequately counter the heat of the sun. Luna 1 overheated and shut down within 36 hours of its launch, and was quietly announced by TASS as the "engineering payload" of an "interplanetary launch vehicle test flight."

Since ancient times, humanity had associated the Moon with causing madness. By mid-1961, engineers on both sides of the planet were convinced that this was completely true.

Despite his run of bad fortune with lunar probes, Mishin was experiencing more success with his other unmanned spacecraft. In particular, by mid-1961 the long-running Sammit programme was starting to reach maturity, with an average of one launch every two months from mid-1960 onwards. The satellite was based around a pressurised module similar to those being used for suborbital biological flights with animals. The pressurised chamber held a 1 m focal length telescope and was attached to a service module which provided the necessary pointing, power and thermal control needed. At the top of the assembly, a small re-entry vehicle was provided to return film to Earth. Early experiments with scanning the film for transmission to Earth had been disappointing, but the system had been retained to enable a “quick look” at important targets before the end of the spacecraft’s nominal 5-10 day mission. Later Sammits carried additional instruments for electronic intelligence gathering (ELINT), for example characterisation of US radar stations and communication frequencies.

After their initial rocky start, Sammit missions now had a success rate approaching 75% and were, along with their US Keyhole counterparts, a significant stabilising element as the Cold War entered its post-Berlin phase. In particular, both sides were able to categorise the other’s ICBM launch sites with reasonable accuracy, providing reassurance that neither Superpower was in danger of falling behind the other. However, it also prompted both sides to re-assess the vulnerability of these large, above-ground launch sites. In the US it was hoped that the Polaris submarine-based missiles would soon reduce this vulnerability, whilst on the Soviet side Yangel updated his R-16 design (which had previously lost out to the R-6 as the main Soviet ICBM) to make it suitable for deployment in hardened silos, from which they could survive and exact revenge for any American first strike.

On the American side, since its early success with Vanguard, the Naval Research Laboratory had found itself overshadowed by the USAF in space achievements. Development of the proposed Vanguard follow-on launcher, originally named Explorer but now called Triton, was floundering as the requirements were continually changed. At first, aware of comparisons with the larger Atlas and future Titan missiles, as well as the Soviet R-6, the Triton’s target payload was upgraded from 700 kg to 5 tonnes. This meant a complete redesign of the launcher, only for Defense Department brass and the White House to demand a justification for why the military needed another booster in this class. So the specification was changed again to 1 tonne, with the intention of filling a gap in small payload launch capabilities. This once more re-set the development clock, so that by the start of 1961 the Navy had still not selected a prime contractor, or indeed finalised the requirements against which the contract could be competed.

The NRL showed itself to be more effective when it came to producing satellites. Building on the earlier experiments with Vanguard 2, in late 1959 the NRL had started a project to develop a weather satellite with a TV imaging capability. This would allow near real time information on cloud cover to be beamed to Earth continuously, greatly aiding the prediction of the weather. As the Navy no longer had their own launcher (and in any case Vanguard would have been underpowered for the mission), it was to be a joint mission with the USAF. The Navy would provide the satellite, the Air Force would provide the ride, and both would share the resulting data between themselves and with the US Weather Bureau. By mid-1960 the Army had also become involved in the programme, providing additional ground station support.

The first dedicated weather satellite, named Iris for the Greek goddess of rainbows, launched from Cape Canaveral on an Atlas-Agena in May 1961. Operating from a 700 km 50 degree orbit, Iris-1 began sending back infrared TV images almost immediately. The images were of poor quality by modern standards, and Iris’ low orbit meant that only small portions of the planet could be viewed at a time, but even with these limitations the satellite represented a revolution in the way in which weather fronts could be tracked. Follow-on spacecraft were launched in September 1961 and February 1962, with plans already in progress for a series of more capable weather satellites to follow.

The Soviets were also aware of the possible benefits to be gained from weather satellites, and the September 1959 decree had included instructions for OKB-385 to develop these over the period 1960-65. Mishin had originally planned to delay deployment of the Meteor weather satellites so they could be launched by his new all-kerolox M-1 rocket, but the success of the American Iris satellite brought pressure to switch Meteor to a different launcher that could be available earlier. The first Meteor satellite was therefore launched in March 1962 on an R-6A/Luna vehicle. With its early teething problems apparently solved, the rocket successfully placed the 4 tonne Meteor into an 80 degree, 500 km orbit. The satellite operated well for over six months, and would be the basic model for Soviet weather satellites for the next five years.

Despite the success of Meteor, communications satellites proved to be a tougher challenge for the Soviets, in particular in achieving the necessary reliability and power needed for components of a resilient active relay system. Although experimental communications satellites would be tested as early as 1963, the first operational Molniya satellites would not be launched until 1966, over four years after the US Army’s first Courier experimental comsat, and two years after AT&T launched their first Telstar satellite. The most significant result of the Molniya project in the early 1960s was that the heavy satellites in their energetic, highly elliptical orbits served as sufficient justification for Mishin to gain authorisation to increase the specification of his M-1 rocket to the point that it would rival Yangel’s U-200 in payload capability.

As for the race to image the far side of the Moon, after Pioneer 2 missed its target and became the world’s first operational interplanetary spacecraft, the goal was finally achieved when the American Pioneer 3 spacecraft made a 1 200 km altitude flyby on 26th October 1961. The black-and-white images returned showed the Lunar farside to be even more rugged than the nearside, with the only significant feature observed being a small, dark oval, similar to the nearside Mares. This new feature was quickly christened “Mare Pasadena” by the JPL imaging team, although this designation would be disputed for some years in the astronomical community.

Just one month later, in November 1961, the Soviet probe Luna 1 (all previous attempts having be retrospectively re-named under the generic “Kosmos” designation) repeated Pioneer’s accomplishment, passing just 800 km above the lunar surface. Unlike the earlier Soviet moonshots, Luna 1 was not a hasty improvisation, but rather the originally intended 400 kg “LNS-1” scientific spacecraft. In addition to the imaging system, instruments were also included to measure particular radiation and magnetic fields, and so after its flyby Luna 1 became the first spacecraft to measure the solar wind from outside of the Earth’s magnetosphere.

Whilst these scientific achievements were very impressive and often had great practical value, it was clear to both sides that, in propaganda terms, there was only one first that really mattered. Who would be the first nation to place a human being into space?

Part I Post #9: Bang, Zoom! Straight to the Moon!

As the Atlas missiles stationed at Vandenberg were being prepared for a possible launch against Moscow in January 1961, another Atlas was undergoing checks at Cape Canaveral with a more peaceful purpose in mind. This was the Atlas-Agena rocket intended for the launch of the world's first deep space probe, Pioneer. The 200 kg spacecraft had been built by the Jet Propulsion Lab as a follow on to their Explorer designs and was intended to make a flyby of the Moon on its way to an independent solar orbit. It carried a number of particle and field sensors, but the highest expectations fell upon its sophisticated camera system. This camera, it was hoped, would at last allow humanity to see what lay on the far side of the Moon. Theories ranged from something essentially identical to the nearside's geography to fanciful suggestions of valleys containing breathable atmospheres, strange Selenite plants, or even a race of advanced Moon-men. Pioneer was intended to settle these questions.

At least it would if it could get off the launch pad. The original launch date of mid-January was postponed at the last minute as the Berlin Crisis was reaching its peak. Although most analysts agreed that it would take a very paranoid Soviet radar operator to interpret the launch as a missile strike, paranoia was very much in the air, and nobody felt that it was worth taking a chance on. The mission was therefore stood down for two weeks whilst the Berlin situation stabilised, and then waited a further two weeks for the Moon to enter a favourable position, with the aim of making a flyby around the time of the New Moon so that the farside would be fully illuminated. However, although the Moon may have been ready by mid-February, it transpired that the launcher was not. The Atlas rocket's core engine failed 45 seconds into the flight, leading to the destruction of the missile by safety officials.

The run of bad luck continued, as a second rocket and spacecraft could not be made ready in time for the March opportunity, whilst the April window was plagued with high cloud cover that would restrict visual tracking of the launch. It was May before the second Pioneer attempt successfully lifted off the pad, but even then the bad luck continued as the Agena upper stage shut down prematurely, stranding Pioneer 1 in a highly-elliptical Earth orbit. The control team at Pasadena were able to operate the spacecraft for several months, validating the imaging system by photographic Earth and using the radiation sensors to explore the Outer Vernov Belts and magnetosphere, but it was hardly the achievement everyone had hoped for. This was especially true at a time when the Air Force was questioning the value of diverting launchers from the vital Keyhole spy missions to Moon probes (disparagingly referred to as "Alices" by the Pentagon brass).

As in many other arenas in the zero-sum game that was the Cold War, America's misfortune was seen as a boon to the Soviets. Mishin had been working hard on his R-6 upper stage (Blok-V) since late 1959, but it was still nominally at least 6 months away from a launch by the start of 1961. His efforts to improve this schedule were hindered by the total lack of assistance from Glushko and Chelomei for his kerolox engine. In fact Mishin was beginning to suspect deliberate sabotage by his “comrades”, perhaps relating to the June 1960 decision by Ustinov to re-allocate development of the manned space capsule from Chelomei to Mishin. Chelomei was not happy with the loss of this prestige project (even if it was intended only as a stop-gap on the way to his Raketoplans), and Mishin felt a definite itching between the shoulder-blades whenever the OKB-1 Chief Designer was in the room. This paranoia appeared be justified when Barmin informed Mishin in late 1960 that there would be a three-month delay in installing liquid oxygen tanks at Tyuratam due to the start of work on facilities for Chelomei's UR-500, a rocket which wasn't scheduled to fly for at least five more years. In this context, Mishin saw the delays being suffered by the Americans as a glimmering opportunity to trump them in a major space "first" and put himself into Khrushchev's good books, hopefully giving him the political leverage to push back against his rival Chief Designers.

To meet this push, Mishin took a savage knife to the Blok-V's development and test schedule, cutting out anything he deemed nonessential. Similarly, the Luna probe he planned to launch was cut down from an ISZ-like science station to little more than a camera attached to a radio, with an attitude control system taken off-the-shelf from the Sammit programme. This could operate either as a fly-by probe to image the farside, or as an impactor that would transmit pictures of the surface before forming the Moon’s first man-made crater. When the technicians at Miass had completed assembly of the probe and announced they were about to start end-to-end electrical tests, Mishin overruled them with a brusque "Test it on the launch pad!"

These herculean efforts meant that Mishin was able to get his uprated R-6A on the launch pad by mid-April 1961. Unlike at the Cape, conditions at Tyuratam were fine for a launch (though many suspected Mishin would have pushed ahead even in a thunderstorm), and the R-6A left the pad at the beginning of its launch window. Despite Mishin's fears that Chelomei might engineer an "accident" to scupper him, the R-6 Blok-A and Blok-B stages worked perfectly, putting the Blok-V/Luna combination into a low elliptical Earth orbit. This hurdle passed, at the appointed time the Blok-V's kerosene/oxygen engine was commanded to fire... and did nothing. The stage refused to light, and within a few hours had drained its batteries, leaving it dead in space.

First launch of the R-6A “Luna” rocket, incorporating Mishin’s kerolox Blok-V upper stage, April 1961.

Over the next week, checks on the two other completed Blok-V's at OKB-385 revealed that both had a wiring fault in the complicated system designed to light the rocket in the zero-gravity, zero-atmosphere environment of space. The fault should have been caught at the design stage, or at least during testing, but Mishin's push to meet an arbitrary schedule had cut those tests out. The problem was corrected and the new stages shipped to Tyuratam in readiness for the next launch window in May. However, this attempt would prove even less successful than the first, as the R-6A’s Blok-B exploded in mid-air before Mishin's stage had a chance to prove itself.

Aware of the risks and unwilling to wait a further month for optimal lighting conditions for a flyby, Mishin had another Luna R-6A standing ready in reserve, and this was rushed to the pad in the following two days to carry out the impactor mission. Finally, on this third attempt, all three stages fired on cue, and the L1-A “Luna 1” probe was placed into its transfer orbit. Unfortunately, the Moon Curse held, as a guidance error meant that the transfer orbit would miss the Moon by almost 100 000 km and head directly into interplanetary space. Even the lesser distinction of launching the first Earth escape spacecraft was diminished when the thermal control systems failed to adequately counter the heat of the sun. Luna 1 overheated and shut down within 36 hours of its launch, and was quietly announced by TASS as the "engineering payload" of an "interplanetary launch vehicle test flight."

Since ancient times, humanity had associated the Moon with causing madness. By mid-1961, engineers on both sides of the planet were convinced that this was completely true.

Despite his run of bad fortune with lunar probes, Mishin was experiencing more success with his other unmanned spacecraft. In particular, by mid-1961 the long-running Sammit programme was starting to reach maturity, with an average of one launch every two months from mid-1960 onwards. The satellite was based around a pressurised module similar to those being used for suborbital biological flights with animals. The pressurised chamber held a 1 m focal length telescope and was attached to a service module which provided the necessary pointing, power and thermal control needed. At the top of the assembly, a small re-entry vehicle was provided to return film to Earth. Early experiments with scanning the film for transmission to Earth had been disappointing, but the system had been retained to enable a “quick look” at important targets before the end of the spacecraft’s nominal 5-10 day mission. Later Sammits carried additional instruments for electronic intelligence gathering (ELINT), for example characterisation of US radar stations and communication frequencies.

After their initial rocky start, Sammit missions now had a success rate approaching 75% and were, along with their US Keyhole counterparts, a significant stabilising element as the Cold War entered its post-Berlin phase. In particular, both sides were able to categorise the other’s ICBM launch sites with reasonable accuracy, providing reassurance that neither Superpower was in danger of falling behind the other. However, it also prompted both sides to re-assess the vulnerability of these large, above-ground launch sites. In the US it was hoped that the Polaris submarine-based missiles would soon reduce this vulnerability, whilst on the Soviet side Yangel updated his R-16 design (which had previously lost out to the R-6 as the main Soviet ICBM) to make it suitable for deployment in hardened silos, from which they could survive and exact revenge for any American first strike.

On the American side, since its early success with Vanguard, the Naval Research Laboratory had found itself overshadowed by the USAF in space achievements. Development of the proposed Vanguard follow-on launcher, originally named Explorer but now called Triton, was floundering as the requirements were continually changed. At first, aware of comparisons with the larger Atlas and future Titan missiles, as well as the Soviet R-6, the Triton’s target payload was upgraded from 700 kg to 5 tonnes. This meant a complete redesign of the launcher, only for Defense Department brass and the White House to demand a justification for why the military needed another booster in this class. So the specification was changed again to 1 tonne, with the intention of filling a gap in small payload launch capabilities. This once more re-set the development clock, so that by the start of 1961 the Navy had still not selected a prime contractor, or indeed finalised the requirements against which the contract could be competed.

The NRL showed itself to be more effective when it came to producing satellites. Building on the earlier experiments with Vanguard 2, in late 1959 the NRL had started a project to develop a weather satellite with a TV imaging capability. This would allow near real time information on cloud cover to be beamed to Earth continuously, greatly aiding the prediction of the weather. As the Navy no longer had their own launcher (and in any case Vanguard would have been underpowered for the mission), it was to be a joint mission with the USAF. The Navy would provide the satellite, the Air Force would provide the ride, and both would share the resulting data between themselves and with the US Weather Bureau. By mid-1960 the Army had also become involved in the programme, providing additional ground station support.

The first dedicated weather satellite, named Iris for the Greek goddess of rainbows, launched from Cape Canaveral on an Atlas-Agena in May 1961. Operating from a 700 km 50 degree orbit, Iris-1 began sending back infrared TV images almost immediately. The images were of poor quality by modern standards, and Iris’ low orbit meant that only small portions of the planet could be viewed at a time, but even with these limitations the satellite represented a revolution in the way in which weather fronts could be tracked. Follow-on spacecraft were launched in September 1961 and February 1962, with plans already in progress for a series of more capable weather satellites to follow.

The Soviets were also aware of the possible benefits to be gained from weather satellites, and the September 1959 decree had included instructions for OKB-385 to develop these over the period 1960-65. Mishin had originally planned to delay deployment of the Meteor weather satellites so they could be launched by his new all-kerolox M-1 rocket, but the success of the American Iris satellite brought pressure to switch Meteor to a different launcher that could be available earlier. The first Meteor satellite was therefore launched in March 1962 on an R-6A/Luna vehicle. With its early teething problems apparently solved, the rocket successfully placed the 4 tonne Meteor into an 80 degree, 500 km orbit. The satellite operated well for over six months, and would be the basic model for Soviet weather satellites for the next five years.

Despite the success of Meteor, communications satellites proved to be a tougher challenge for the Soviets, in particular in achieving the necessary reliability and power needed for components of a resilient active relay system. Although experimental communications satellites would be tested as early as 1963, the first operational Molniya satellites would not be launched until 1966, over four years after the US Army’s first Courier experimental comsat, and two years after AT&T launched their first Telstar satellite. The most significant result of the Molniya project in the early 1960s was that the heavy satellites in their energetic, highly elliptical orbits served as sufficient justification for Mishin to gain authorisation to increase the specification of his M-1 rocket to the point that it would rival Yangel’s U-200 in payload capability.

As for the race to image the far side of the Moon, after Pioneer 2 missed its target and became the world’s first operational interplanetary spacecraft, the goal was finally achieved when the American Pioneer 3 spacecraft made a 1 200 km altitude flyby on 26th October 1961. The black-and-white images returned showed the Lunar farside to be even more rugged than the nearside, with the only significant feature observed being a small, dark oval, similar to the nearside Mares. This new feature was quickly christened “Mare Pasadena” by the JPL imaging team, although this designation would be disputed for some years in the astronomical community.

Just one month later, in November 1961, the Soviet probe Luna 1 (all previous attempts having be retrospectively re-named under the generic “Kosmos” designation) repeated Pioneer’s accomplishment, passing just 800 km above the lunar surface. Unlike the earlier Soviet moonshots, Luna 1 was not a hasty improvisation, but rather the originally intended 400 kg “LNS-1” scientific spacecraft. In addition to the imaging system, instruments were also included to measure particular radiation and magnetic fields, and so after its flyby Luna 1 became the first spacecraft to measure the solar wind from outside of the Earth’s magnetosphere.

Whilst these scientific achievements were very impressive and often had great practical value, it was clear to both sides that, in propaganda terms, there was only one first that really mattered. Who would be the first nation to place a human being into space?

It just occurred to me. ITTL, it's the US who are attaining the Firsts, yet it's the USSR who deliver the big science return value. You can bet the Politburo will be taking full advantage of that department with regards to PR.

And Mishin's Bruiser Attitude hurting here already, with their attempts to upstage the US failing through inadequate testing of their equipment - and then only when it was tested at all.

As for the next big step, the Man in LEO. Neither side appears to have a distinct advantage at this point, which means for now, for me, it's anyone's game.

And Mishin's Bruiser Attitude hurting here already, with their attempts to upstage the US failing through inadequate testing of their equipment - and then only when it was tested at all.

As for the next big step, the Man in LEO. Neither side appears to have a distinct advantage at this point, which means for now, for me, it's anyone's game.

It just occurred to me. ITTL, it's the US who are attaining the Firsts, yet it's the USSR who deliver the big science return value. You can bet the Politburo will be taking full advantage of that department with regards to PR.

Indeed. However I would expect that to change if not for the usual one Cold War flag waiving but for other purposed. The big winner here is the science community and Humanity in general. Nothing like competition to bring out the best in us...usually.

And Mishin's Bruiser Attitude hurting here already, with their attempts to upstage the US failing through inadequate testing of their equipment - and then only when it was tested at all.

Is this typical of the Soviet space program in OTL or is this just TTL's rush?

As for the next big step, the Man in LEO. Neither side appears to have a distinct advantage at this point, which means for now, for me, it's anyone's game.

I agree. Though I had an image in my head of both sides getting up there roughly the same time (i.e. got a guy up there at the same time) with the capsules passing by close enough for the two to glare at each other. Not likely but in my mind it was kind of hilarious.

very good new chapter . NASA And the Soviets , are discovering what the Far side of the Moon , i hope soon NASA will Land on the Moon , and later a Joint Moonbase with ESA and the Russians. Cant hardly wait for the next chapters .

I don't see e of pi accusing you of making the Soviets improbably competent--and by gosh, they're not!

I'd like to point out the bizarre mixing-matching going on between the rivals--one side is focusing on its Man in Space Soonest capsule being lifted on a two-stage rocket with Atlas as one stage and a hypergolic upper stage (is it one and the same with OTL Agena, with the same name even?--I note this was Lockheed's successful bid for a contract OTL by the way), whereas the other, having successfully launched satellites with a single hypergolic stage vehicle, now want to add a ker-lox upper stage. Of course this kind of thing went on OTL all the time but it makes me wonder, why doesn't anyone go with their strengths and having made a successful engine/tank combo using one mix, follow through with making upper stages of the same design philosophy?

In Russia, there's clearly a desire to not throw away the talents of even designers such as Mishin who won't get with the current program, and I suppose a hope that if they back all possible propellant strategies one will emerge as the best, or in a given state of the art pull ahead of the best that was standard before. But was it necessary to promise Mishin he could try out the second stage for the R-6 no matter what?

Perhaps I'm consistently misspeaking the number of stages for the R-6--OTL Korolev went for parallel staging, with all 5 engines lit on the ground, in his R-7, and Atlas also did the same thing, because these were early ker-lox engines and there was some concern they would not light successfully in the middle of the burn. But with hypergolic engines as on the R-6, one has great confidence they will light so if I go back I'll probably find the R-6 was two-stage from the get-go, so we are talking about adding on third stages.

Which helps explain why the Americans are switching to hypergolic for their upper stage; indeed OTL ker-lox upper stages have never been very popular; they tend to either be hypergolic (or solid) for reliability, or to be hydrogen-burners, for the extra ISP when achieving high thrust is no longer so paramount as it is with the launch stage(s). So the American behavior is reasonable and indeed parallel to OTL (just not for a manned launch--we used hypergols for Gemini, but that was hypergolic all the way on a Titan II).

Why then are the Soviets letting Mishin hold up the show with trying to perfect a ker-lox upper stage against all Soviet conventional wisdom, requiring their launcher to accommodate LOX cryogenics and a fourth propellant (kerosene) as well, creating the time constraints cryogenics cause while still retaining the worst of the liability of the hypergolics (most of the propellant mass is still in the first stage, which is hypergolic after all)?

Is this an evolutionary plan, hoping to get some early experience with cryogenics, looking ahead to ambitious plans to use hydrogen? Or is it just Kremlin porkbarrel politics, with Mishin getting a booby prize to keep him in the design game?

If the combined rocket could only launch successfully, a LOX stage with leftover propellant is actually sort of storable, depending on the orbit, exposure to sunlight, and thermal management of the stage the oxygen might last a long time. So it is worth practicing I suppose. But this Mishin stage is not designed for that I gather; it will burn up all its propellant pushing payload into orbit and so a stage to develop Soviet art of storing LOX in orbit for long periods would have to be yet another stage on top of all this.

As much as I hate hypergolics my advice to the Kremlin at this stage would be to keep going with them for a while, as the advantages ker-lox offers mainly dominate when one goes over to it completely, which is too many steps to retrace now. I'd think that if they either bypassed Mishin or got him to get with the current program they'd have a reliable upper stage hypergolic by now.

I'd like to point out the bizarre mixing-matching going on between the rivals--one side is focusing on its Man in Space Soonest capsule being lifted on a two-stage rocket with Atlas as one stage and a hypergolic upper stage (is it one and the same with OTL Agena, with the same name even?--I note this was Lockheed's successful bid for a contract OTL by the way), whereas the other, having successfully launched satellites with a single hypergolic stage vehicle, now want to add a ker-lox upper stage. Of course this kind of thing went on OTL all the time but it makes me wonder, why doesn't anyone go with their strengths and having made a successful engine/tank combo using one mix, follow through with making upper stages of the same design philosophy?

In Russia, there's clearly a desire to not throw away the talents of even designers such as Mishin who won't get with the current program, and I suppose a hope that if they back all possible propellant strategies one will emerge as the best, or in a given state of the art pull ahead of the best that was standard before. But was it necessary to promise Mishin he could try out the second stage for the R-6 no matter what?

Perhaps I'm consistently misspeaking the number of stages for the R-6--OTL Korolev went for parallel staging, with all 5 engines lit on the ground, in his R-7, and Atlas also did the same thing, because these were early ker-lox engines and there was some concern they would not light successfully in the middle of the burn. But with hypergolic engines as on the R-6, one has great confidence they will light so if I go back I'll probably find the R-6 was two-stage from the get-go, so we are talking about adding on third stages.

Which helps explain why the Americans are switching to hypergolic for their upper stage; indeed OTL ker-lox upper stages have never been very popular; they tend to either be hypergolic (or solid) for reliability, or to be hydrogen-burners, for the extra ISP when achieving high thrust is no longer so paramount as it is with the launch stage(s). So the American behavior is reasonable and indeed parallel to OTL (just not for a manned launch--we used hypergols for Gemini, but that was hypergolic all the way on a Titan II).

Why then are the Soviets letting Mishin hold up the show with trying to perfect a ker-lox upper stage against all Soviet conventional wisdom, requiring their launcher to accommodate LOX cryogenics and a fourth propellant (kerosene) as well, creating the time constraints cryogenics cause while still retaining the worst of the liability of the hypergolics (most of the propellant mass is still in the first stage, which is hypergolic after all)?

Is this an evolutionary plan, hoping to get some early experience with cryogenics, looking ahead to ambitious plans to use hydrogen? Or is it just Kremlin porkbarrel politics, with Mishin getting a booby prize to keep him in the design game?

If the combined rocket could only launch successfully, a LOX stage with leftover propellant is actually sort of storable, depending on the orbit, exposure to sunlight, and thermal management of the stage the oxygen might last a long time. So it is worth practicing I suppose. But this Mishin stage is not designed for that I gather; it will burn up all its propellant pushing payload into orbit and so a stage to develop Soviet art of storing LOX in orbit for long periods would have to be yet another stage on top of all this.

As much as I hate hypergolics my advice to the Kremlin at this stage would be to keep going with them for a while, as the advantages ker-lox offers mainly dominate when one goes over to it completely, which is too many steps to retrace now. I'd think that if they either bypassed Mishin or got him to get with the current program they'd have a reliable upper stage hypergolic by now.

Bahamut-255 said:It just occurred to me. ITTL, it's the US who are attaining the Firsts, yet it's the USSR who deliver the big science return value. You can bet the Politburo will be taking full advantage of that department with regards to PR.

Shadow Knight said:Indeed. However I would expect that to change if not for the usual one Cold War flag waiving but for other purposed. The big winner here is the science community and Humanity in general. Nothing like competition to bring out the best in us...usually.

Partly this is down to luck, as several of the simpler spacecraft that the Soviets intend to launch first get lost due to launcher problems, so when those get ironed out it’s the larger, more complex spacecraft that are plucked off the shelf as ready to go. The Americans OTOH tend to prefer to stick with a simpler spacecraft until they’re sure the launcher bugs are worked out, only then trusting their more complex (and expensive) spacecraft.

AFAIK the Soviet space science community even IOTL was relatively open with their results, and this is in the middle of Khrushchev’s relaxation of cultural and academic controls, so the whole world is benefitting from the results - whilst of course the Soviets bag some bragging rights!

Bahamut-255 said:And Mishin's Bruiser Attitude hurting here already, with their attempts to upstage the US failing through inadequate testing of their equipment - and then only when it was tested at all.

Shadow Knight said:Is this typical of the Soviet space program in OTL or is this just TTL's rush?

It’s typical of the Soviet space programme in OTL - and indeed other space programmes that are driven more by political needs than hard engineering. In the West, the usual solution is to massively inflate the budget and/or schedule to compensate (Constellation, Galileo), but where that’s not possible failure is often the result (Beagle 2 being a good example).

OTL showed quite well how Mishin dealt with stress and deadlines - by cutting corners and drinking hard. Here the stress is significant, though not at the same level as during OTL’s N-1 development, so the damage to his liver, whilst still high, is somewhat reduced.

Bahamut-255 said:As for the next big step, the Man in LEO. Neither side appears to have a distinct advantage at this point, which means for now, for me, it's anyone's game.

Shadow Knight said:I agree. Though I had an image in my head of both sides getting up there roughly the same time (i.e. got a guy up there at the same time) with the capsules passing by close enough for the two to glare at each other. Not likely but in my mind it was kind of hilarious.

We’ll find out in the next update

Astronomo2010 said:very good new chapter . NASA And the Soviets , are discovering what the Far side of the Moon , i hope soon NASA will Land on the Moon , and later a Joint Moonbase with ESA and the Russians. Cant hardly wait for the next chapters .

Small moves, Ellie…

Shevek23 said:I'd like to point out the bizarre mixing-matching going on between the rivals--one side is focusing on its Man in Space Soonest capsule being lifted on a two-stage rocket with Atlas as one stage and a hypergolic upper stage (is it one and the same with OTL Agena, with the same name even?--I note this was Lockheed's successful bid for a contract OTL by the way), whereas the other, having successfully launched satellites with a single hypergolic stage vehicle, now want to add a ker-lox upper stage. Of course this kind of thing went on OTL all the time but it makes me wonder, why doesn't anyone go with their strengths and having made a successful engine/tank combo using one mix, follow through with making upper stages of the same design philosophy?

On the US side, the developments are pretty much as per OTL. As you’ve correctly surmised, Agena ITTL is pretty much identical to Agena IOTL. The Agena contract was awarded in 1956, so is still inside the ‘soft butterfly net’ applying to US space developments before October 1957 ITTL. One difference is IOTL agena was first paired with Thor, leading eventually to the Delta rocket family. ITTL they go straight to Atlas, and Thor remains just an IRBM.

Similarly, TTL’s Mercury is very similar to OTL’s (which is why I kept the name), largely down to form following function (especially when Max Faget is dictating the form).

Shevek23 said:In Russia, there's clearly a desire to not throw away the talents of even designers such as Mishin who won't get with the current program, and I suppose a hope that if they back all possible propellant strategies one will emerge as the best, or in a given state of the art pull ahead of the best that was standard before. But was it necessary to promise Mishin he could try out the second stage for the R-6 no matter what?

<snip>

Why then are the Soviets letting Mishin hold up the show with trying to perfect a ker-lox upper stage against all Soviet conventional wisdom, requiring their launcher to accommodate LOX cryogenics and a fourth propellant (kerosene) as well, creating the time constraints cryogenics cause while still retaining the worst of the liability of the hypergolics (most of the propellant mass is still in the first stage, which is hypergolic after all)?

On the Soviet side, the propellant mix comes down to politics. Chelomei inherited R-6 from Sinilshchikov, and has minimal interest in developing it further, preferring to move on to his more advanced Universal Rocket system (Yangel’s R-200 and his own UR-500). Mishin, you’ll recall, was given kerolox development in the late ‘50s basically to shunt him out of the way and because no-one else was interested in taking on the technology, so he’s been developing it for some time. Along with his being assigned small early probes and satellites (again, because Chelomei is focussed on his more capable Raketoplan system), he needs an upper stage to boost R-6’s performance in the short term. It’s less that Mishin was “promised” he could try out Blok-V on R-6, more that he was able to take advantage of the other Chief Designers’ distraction with their other projects to push his own agenda. Blok-V lets him trial the technology (which he’s planning to use on his larger all-kerolox M-1) whilst achieving some propaganda wins (for him personally, in his battle with Chelomei - with the benefit to the USSR being almost incidental) .

For hypergolic upper stages, these are being developed by Chelomei as part of the Raketoplan system.

So single-propellant rockets are coming on the Soviet side (R-200 and UR-500 with storables, M-1 with kerolox), but aren’t yet ready.

On the US side… we’ll find out in Part II!

Shevek23 said:Perhaps I'm consistently misspeaking the number of stages for the R-6--OTL Korolev went for parallel staging, with all 5 engines lit on the ground, in his R-7, and Atlas also did the same thing, because these were early ker-lox engines and there was some concern they would not light successfully in the middle of the burn. But with hypergolic engines as on the R-6, one has great confidence they will light so if I go back I'll probably find the R-6 was two-stage from the get-go, so we are talking about adding on third stages.

R-6 is a two-stage rocket, with Blok-V being the third stage of the R-6A (V being the third letter of the cyrillic alphabet). The illustration in the post shows the full stack shortly after launch, with Blok-V and the Luna spacecraft concealed under the fairing. Use of hypergolics meant there was less concern about air-lighting the Blok-B of the R-6 ICBM, so no push for parallel staging during its development. Here’s a closer look at the R-6 ICBM (with the original, flawed nosecone):

Now a brief production note. The post on this coming Sunday 13th July will be the last of Part I. Part II is coming together, but is not yet quite ready, so there will be a break of one month before we start with that. So expect Part II Post#1 to appear on Sunday 10th August. I’ll try to make sure it’s worth the wait

Man I am LOVING this TL.

I can't wait to see who get's a man into space first.

Speaking of which, what happens to Yuri Gagarin in this TL?

I can't wait to see who get's a man into space first.

Speaking of which, what happens to Yuri Gagarin in this TL?

And the comrade women?

OTL Gagarin was first of Korolev's "Eagles." Going back to the Thirties was an ideological desire to promote first of all Soviets of impeccably working-class backgrounds. This was complicated by the fact that in the 1920s not only NEP but the general victory of the Bolsheviks in the Civil War brought in lots of Russians of distinctly bourgeois background as belated supporters of the Soviet state, as the standing representative of Russian power and dignity. Korolev favored Gagarin among other cosmonaut candidates for his distinctively proletarian background, just as among the women Valentina Tereshkova benefited from a pure working-class pedigree. Other women were more qualified as aviators and engineers, but "suffered" from a more bourgeois background; their family heritage meant they knew more, had flown more, but weren't as representative of the new Soviet woman as the more lowly Tereshkova's ancestry.

I'd think that gleaning from the whole Soviet Union there is at least a chance both Gagarin and Tereshkova are bypassed, but perhaps the limited numbers of candidates who pass both the minimal bars of technical competence and the ideological trifecta are such that the same individuals rise to the top of the lottery.

So regarding the women--they are somewhat smaller in mass; an ultra-rational Soviet state would favor them over men, and go for the Bolshevik coup of Leninist style feminism. OTL Korolev would not think of sending up a woman first. Odds are I guess Chelomei would not differ from him in his reflexive patriarchy. Does anyone know any different--would Chelomei be more open to the radical Bolshevism that says that if a woman is more rational for the job, than of course Leninist rationality would set aside bourgeois "chivalry" and send up a woman first? And could this woman be someone other than Tereshkova, who did not react well to microgravity, even if it mean that other woman would be of a less impeccably proletarian background?

Even if the first Soviet citizen in orbit is female, is there any chance than the subsequent roster of cosmonauts selected for orbital missions and perhaps beyond will be roughly equal in gender distribution, or will the Soviets as per OTL send up one token woman, and then go over to an all-male launch roster until the Americans finally get around to scheduling a woman for launch?

My guess is, the more confident the Soviet rocketeers are that their mission will go nominally, or that anyway the escape systems are such that the cosmonaut is assured of survival even if the mission fails, that they will bow to the logic of women massing less then men and take the Bolshevik reward of gender equity and assign a woman to the first launch, or if not the first, then an equal role in later launches. But if there is some doubt of the cosmonaut surviving, they will all be men.

How likely the author thinks that the same cosmonaut candidates chosen OTL will be chosen here will be an interesting thing to learn. Of course the author can interject as much chaos as he likes in the identities of the cosmonaut candidates--mere survival of the Great Patriotic War is a major roll of the dice, as is survival of nine more years of Stalin postwar--anyone's family can have been arbitrarily chosen for disgrace, opening up opportunities for people completely unheard of OTL.

OTL Gagarin was first of Korolev's "Eagles." Going back to the Thirties was an ideological desire to promote first of all Soviets of impeccably working-class backgrounds. This was complicated by the fact that in the 1920s not only NEP but the general victory of the Bolsheviks in the Civil War brought in lots of Russians of distinctly bourgeois background as belated supporters of the Soviet state, as the standing representative of Russian power and dignity. Korolev favored Gagarin among other cosmonaut candidates for his distinctively proletarian background, just as among the women Valentina Tereshkova benefited from a pure working-class pedigree. Other women were more qualified as aviators and engineers, but "suffered" from a more bourgeois background; their family heritage meant they knew more, had flown more, but weren't as representative of the new Soviet woman as the more lowly Tereshkova's ancestry.

I'd think that gleaning from the whole Soviet Union there is at least a chance both Gagarin and Tereshkova are bypassed, but perhaps the limited numbers of candidates who pass both the minimal bars of technical competence and the ideological trifecta are such that the same individuals rise to the top of the lottery.

So regarding the women--they are somewhat smaller in mass; an ultra-rational Soviet state would favor them over men, and go for the Bolshevik coup of Leninist style feminism. OTL Korolev would not think of sending up a woman first. Odds are I guess Chelomei would not differ from him in his reflexive patriarchy. Does anyone know any different--would Chelomei be more open to the radical Bolshevism that says that if a woman is more rational for the job, than of course Leninist rationality would set aside bourgeois "chivalry" and send up a woman first? And could this woman be someone other than Tereshkova, who did not react well to microgravity, even if it mean that other woman would be of a less impeccably proletarian background?

Even if the first Soviet citizen in orbit is female, is there any chance than the subsequent roster of cosmonauts selected for orbital missions and perhaps beyond will be roughly equal in gender distribution, or will the Soviets as per OTL send up one token woman, and then go over to an all-male launch roster until the Americans finally get around to scheduling a woman for launch?

My guess is, the more confident the Soviet rocketeers are that their mission will go nominally, or that anyway the escape systems are such that the cosmonaut is assured of survival even if the mission fails, that they will bow to the logic of women massing less then men and take the Bolshevik reward of gender equity and assign a woman to the first launch, or if not the first, then an equal role in later launches. But if there is some doubt of the cosmonaut surviving, they will all be men.

How likely the author thinks that the same cosmonaut candidates chosen OTL will be chosen here will be an interesting thing to learn. Of course the author can interject as much chaos as he likes in the identities of the cosmonaut candidates--mere survival of the Great Patriotic War is a major roll of the dice, as is survival of nine more years of Stalin postwar--anyone's family can have been arbitrarily chosen for disgrace, opening up opportunities for people completely unheard of OTL.

AFAIK the Soviet space science community even IOTL was relatively open with their results, and this is in the middle of Khrushchev’s relaxation of cultural and academic controls, so the whole world is benefitting from the results - whilst of course the Soviets bag some bragging rights!

It could have something to do with the fact that the USSR wanted western confirmation that they had achieved what they claimed. The Soviets worked with Jodrell Bank to ensure that their satalites could be tracked successfully:

In a sense, the USSR also used the capabilities of Jodrell Bank. In many circles the first Soviet lunar probe, Luna 1, launched on 2 January 1959, was simply not believed to have existed. This must have annoyed the Soviet authorities enormously, despite the fact that the transmission frequencies were announced directly after launch. For their second successful launch they decided to try to engage Jodrell Bank as a source of independent verification of any claim of success. Therefore the USSR sent detailed instructions to Jodrell Bank how to find their second lunar probe, Luna 2, that was launched on 12 September 1959 and hit the moon the next day. Jodrell Bank provided scientific proof that Luna 2 actually reached the moon, and the USSR continued to provide pointing and frequency data to Jodrell Bank for a number of years.

Incidentally, although I haven't commented before, I am enjoying this timeline. I especially like the political changes triggered by a different Space Race.

One minor cultural change ITTL is that the Goons record A Russian Love Song will have been butterflied away, which means that the world will miss out on Spike Milligan's Elvis impression.

Cheers,

Nigel.

Drunken_Soviet said:Man I am LOVING this TL.

I can't wait to see who get's a man into space first.

Speaking of which, what happens to Yuri Gagarin in this TL?

Glad you’re enjoying it, tovarishch! We’ll be dealing with manned spaceflight in the next post, so for now that’s all I have to say on the topic!

Shevek23 said:And the comrade women?

This will be explored more later, but regarding the general points you’ve made, working-class credentials will definitely matter to selection chances, but slightly less than was the case IOTL (reflecting the lower propaganda value the Soviets have experienced to date ITTL - still significant, but not at OTL Sputnik Shock levels).

On women in general, Marxist-Leninist ideals here will run smack into traditional Russian patriarchal sentiment (and the more general male-oriented world of the 1960s - you may have noticed I’ve tended to use “Man in space” terms rather than more modern constructions, as this is how the leaders and engineers of the time were thinking). Even as recently as 2008, Russian space officials were blaming the wide landing of the Soyuz TMA-11 mission on the fact the capsule contained more women than men, a situation that the then-head of Roskosmos Anatoly Perminov assured us would not be allowed to happen again

Anatoly Perminov said:Of course in the future, we will work somehow to ensure that the number of women will not surpass [the number of men]. <snip> This isn't discrimination, I'm just saying that when a majority [of the crew] is female, sometimes certain kinds of unsanctioned behaviour or something else occurs.

Regarding the lower mass of women, this isn’t a significant factor given the margins available with Soviet rockets (though as I mentioned before, on long interplanetary missions or space stations I think an all-female crew would offer significant mass savings on consumables). It would actually make more sense for the tiny, cramped US Mercury capsules (or OTL’s Gemini, nicknamed the Gusmobile because Grissom was the only astronaut small enough to feel comfortable inside it), but the USAF of the ‘60s doesn’t have many female test pilots either…

On cosmonaut selections, more to come...

NCW8 said:It could have something to do with the fact that the USSR wanted western confirmation that they had achieved what they claimed. The Soviets worked with Jodrell Bank to ensure that their satalites could be tracked successfully

IIRC they were less than happy about Jodrell Bank confirming their image of the Lunar farside by publishing it before they did

NCW8 said:Incidentally, although I haven't commented before, I am enjoying this timeline. I especially like the political changes triggered by a different Space Race.

Glad you’re enjoying it, Nigel! There will be more to come on political impacts in Part II.

NCW8 said:One minor cultural change ITTL is that the Goons record A Russian Love Song will have been butterflied away, which means that the world will miss out on Spike Milligan's Elvis impression.

Unfortunately the Spaßpolizei won’t let me see the video, so I’m left to wonder at the notion of Milligan doing Elvis

IIRC they were less than happy about Jodrell Bank confirming their image of the Lunar farside by publishing it before they didIn general though a good point, and better than some of the other schemes they were considering to ensure the world believed them (e.g. by nuking the Moon - seriously!).

It was actually pictures sent from the surface of the moon by Luna 9, the first probe to land on the moon. The pictures were sent using the international facsimile standard, and apparently were recognised by the PR man at Jodrell Bank because he had previously heard such signals when he used to work for a newspaper. They actually had to borrow a facsimile receiver from the Daily Express in Manchester to print the pictures. That's probably one reason why the pictures were published in a British newspaper so quickly, although Bernard Lovell would have been keen to get publicity for Jodrell Bank anyway.

Jodrell Bank gained a lot of publicity from their tracking of the Soviet space probes - they were one of the few facilities that could track the carrier stages of Sputnik 1 and 2. ITTL, they'll have a bit less publicity and that could reduce the funding for the telescope.

Unfortunately the Spaßpolizei won’t let me see the video, so I’m left to wonder at the notion of Milligan doing ElvisMaybe ITTL he could brush up his Eddie Rosner impression and sing a Red-jazz tinged “American Love Song” instead?

Schade, Schade ! At least you can read the lyrics here.

We meet each night by the silvery light of that

dear old fashioned Russian satellite moon

It shines so bright -- turns Americans white

at the sight of our dear old Russian satellite moon

Cheers,

Nigel.

Last edited:

Part I Post #10: The First Man

So today we come at last to the final Post of Part I of...

Part I Post #10: The First Man

At the start of the 1960s, the US and the USSR each had two parallel man-in-space efforts underway. In the Soviet Union, Chelomei’s long-term Raketoplan space plane project ran alongside the underfunded capsule programme, operating under the code-name Zarya (“Dawn”), which had been reallocated from Chelomei to Mishin in 1960 under pressure from Ustinov. The United States mirrored this situation, with the Air Force focussing first and foremost on their Dynasoar space plane, whilst the Mercury capsule programme was seen as a cheap stop-gap. The leadership of both sides were interested in what data capsule flights could provide with respect to how men could adapt to the space environment, and accepted there would be significant propaganda value in launching the first human space explorer, but few on either side saw capsules as leading to any significant military operational capability. An additional factor in the US was that Eisenhower had become more concerned with slowing the growth of the Military-Industrial Complex than competing with the Russians in space stunts, even after the flight of Vega the dog again highlighted the political benefits that could accrue.

The situation for Mercury changed with the inauguration of President Nixon. Taking his oath of office under the shadow of the Berlin Crisis and possible nuclear war had a huge impact on the shape of Nixon’s term of office. Although still a staunch anti-communist and a firm believer in the long-standing policy of containment of Soviet influence, the near-miss of Berlin convinced Nixon that direct confrontations between the two world systems had to be avoided in the future. Nixon’s policy, encapsulated in his famous “Not One Step More” speech in Bonn, instead became to “freeze” the Cold War in its current configuration, with both sides sticking to their current spheres of influence and not attempting to shift the borders between the First and Second Worlds by military means. Nixon would continue to expand the US’ military forces to ensure they would be ready for anything, but he also wanted to focus on beating Communism through the increased economic and technological dynamism of the Free World, ensuring that America stayed ahead of the Communists and would eventually begin to widen the gap again. Hopefully this would open up new options in the future for defeating the Communist system, or at least in coming to some sort of stable accommodation without recourse to nuclear war.

As a highly visible demonstration of technological prowess, space was to be a vital front in Nixon’s Cold War strategy. Shortly after taking office he created the Defense Research Agency as an independent R&D arm under the Pentagon with the aim of developing new, breakthrough technologies to augment and secure the defence capabilities of the United States. The DRA would consolidate, coordinate and complement the R&D efforts of the individual services, bring new expertise and new funding to ensure that the American military would remain the most technically advanced in the world, with its Space Systems Office having a particular focus on launch vehicle development. In conjunction with this change, the Nixon administration moved to formally incorporate space technology into the NACA’s remit, so that from November 1961 it became the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics and Astronautics (NACAA), gaining new funding and new personnel to support its work in fundamental research in support of air and space transportation.

Both of these changes had the effect of supercharging the ongoing Dynasoar programme, including its associate launch vehicle development, but of the most immediate impact was on Mercury. With the new focus on being seen to be ahead of the Soviets, the potential of Mercury to extend an early lead made it very attractive. Dynasoar, whilst considered valuable and worthwhile, was not scheduled to begin airborne glide tests until 1963, with the first space launch not coming until at least a year later. Mercury could guarantee to put a man in space within Nixon’s first term. Suddenly, Max Faget’s lonely team of ballistics advocates found themselves with more friends and resources than they could have dreamed of a year earlier.

Following a series of wind-tunnel assessments and Redstone-launched suborbital flights of aerodynamic test vehicles throughout 1961, by the start of 1962 the final configuration of the Mercury capsule had been fixed. Mercury would be a small, conical capsule, 1.9 m in diameter - just big enough for a single occupant. Although the Air Force still used the term “pilot”, for the first few flights at least it was possible that the man inside the capsule would be little more than a passenger along for the ride. Although controls were included to allow the pilot to turn the craft in space and fire the retro-thrusters, the mission could be completely automated, with critical events verified by ground control. If the alien environment of outer space were to somehow incapacitate the pilot it would be vital to be able to bring him home with the automatic systems. Assuming that the first candidates showed no adverse effects, future pilots would test manual operation of the vehicle, providing valuable feedback into the design and concept of operations for Dynasoar.

In January 1962 the production model Mercury capsule made its first short flight when the Escape Tower rocket that would pull the capsule clear of its launcher in the event of a catastrophe succeeded in yanking a Mercury off its test stand at the NACAA Wallops Island facility. The first test of a full-up Mercury from the top of a missile came the following May, when a modified Redstone was fired at the Cape, lobbing the Mercury capsule over 350 km and reaching a maximum altitude of 200 km. On board was a Rhesus monkey named “Bucky”, who survived the experience with no ill effects, giving confidence that a man would be able to survive the experience equally well.

This mission, MR-5, was planned to be the last Mercury-Redstone flight, as the increased priority from the White House and the DRA succeeded in persuading the Air Force to allocate models of the more powerful Atlas-D missile to the Mercury test programme. However, the first Mercury-Atlas launch at the end of May was unsuccessful, with the booster engines cutting out just seconds after ignition, causing minor damage to the rocket and the launch pad. Further test flights in June and July showed better results, the latter test boosting the unmanned capsule into a low Earth orbit, although a failure of the retro-boosters meant that it was unable to return to Earth as planned. Finally, in August Ham the Chimp completed a suborbital flight on mission MA-4.

Ham and Bucky both became minor celebrities in the US, frequently appearing on television throughout the remainder of 1962. This level of fame was not matched by the canine cosmonauts of Soviet space tests of that period. The flight of Vega in April 1960 had been a publicity coup for the USSR, but only because of a cover-up. Launched aboard a hasty modification of the Sammit re-entry vehicle, Vega was killed when the parachute of the tiny capsule failed. The resulting impact was potentially survivable for the hardened film canister of a spy satellite, but not for a living creature. The broadcasting via TASS of Vega’s barks whilst she had been on-orbit meant that the Soviets couldn’t simply deny the mission had ever happened, and so a replacement dog had been found to stand in for Vega at the following May Day parade. Although the Soviets got away with this deception for many decades, they were unwilling to take similar propaganda risks in the future, and so all biological test flights were put on hold. When flights with dogs resumed in mid 1961, they were carried out with no publicity at launch, and were simply noted as “Space technology test vehicles”. Only after the safe return of the subject would the mission’s true purpose be announced, with unsuccessful missions quietly omitted.

Following Vega’s death, future biological missions would be flown using a new re-entry vehicle design. After considering use of a simple spherical capsule, Mishin and Tikhonravov decided instead to develop a headlamp-shaped vehicle. This decision was taken with an eye to the future. The decree of September 1959 that had authorised the start of work on Zarya was primarily a child of Chelomei, and made it very clear that it was OKB-1’s Raketoplans that would be the vehicle enabling Soviet space travel in the long term. Chelomei planned for Zarya to be just a test programme on the path to Raketoplan, an unfortunately necessary step which could be safely farmed out to Mishin without harming his grand scheme.

For Mishin then, Zarya was his first, last and only chance to establish a foothold in manned spaceflight, and so he intended to make sure that, rather than a dead-end test vehicle, whatever flew would be expandable and upgradeable to support future space spectaculars which would advance Mishin’s position vis-a-vis Chelomei. A spherical re-entry vehicle, though providing superior stability, would result in gee forces unsuitable for future deep space missions. Therefore Mishin contracted with Keldysh’s Central Aerohydrodynamic Institute (Tsentralniy Aerogidrodinamicheskiy Institut, TsAGI) to propose an alternative shape which would provide some lift and steering capability whilst minimising mass. The resulting headlamp shaped capsule would be suitable for high-orbit and even lunar missions, but required use of a sophisticated active attitude control system to maintain stability during re-entry. Though the experience gained with the Sammit pointing mechanism and efforts to improve the accuracy of ICBM warheads had given some experience in this field, the complexity of the system needed still posed a significant challenge to Mishin’s engineers.

These challenges were finally overcome in February 1962, when an R-6 missile was rolled out to the pad at Tyuratam carrying the 4 tonne Zarya capsule at its tip. The rounded 2 m wide re-entry capsule (Spuskaemyi Apparat, SA) formed the nose of the rocket, with the short Sammit-derived instrument module (Pribornyy Apparat, PA) concealed under a conical supporting fairing, although for this first test flight a non-functional mock-up was in place. Inside the Zarya was another dog-cosmonaut, a male named Baikal, but this time he would only be making a suborbital hop of around 1 000 km, as without a functional service module it would be impossible to conduct the necessary retro-burn.

The first suborbital test flight however ended in disappointment, as the Zarya SA failed to separate from the R-6 second stage, and the entire complex impacted together, killing Baikal. Despite this, March saw another fearless dog, optimistically named “Vezuchiy” (“Lucky”) launch atop an R-6. Vezuchiy lived up to her name, successfully landing in central Siberia from where her Zarya capsule was retrieved less than six hours after launch.

Further suborbital flights throughout the spring and summer of 1962 were mostly successful, leading up to the first orbital flight launched on an R-6A ‘Luna’ rocket at the end of August, once again piloted by the fearless Vezuchiy. Coming less than a week after Ham’s flight, this mission made Vezuchiy the first living entity to travel into space more than once. Her reputation was slightly tarnished when the Zarya capsule landed over 300 km off target, but aside from this the mission was a complete success, with Vezuchiy completing five orbits of the Earth. Following her retrieval, a confident Mishin declared that, assuming the next two test flights went as planned, he would be ready to launch a manned mission in time for the 45th anniversary of the Revolution in November 1962. The race was tightening.

The successful mission of Vezuchiy, coming so close to that of Ham, focussed attention in the US on just how tight the race had become. The Air Force’s original plan had been to launch at least two, more probably three more “Astrochimp” missions before attempting to launch a man into orbit. This was partly to gather more data on the biological effects of spaceflight, but also to improve confidence in the Mercury capsule, in particular the retro booster control system, which had given some trouble on the second unmanned flight. But following this methodical test regime could risk letting the Reds beat them into space, with some in the chain of command of the opinion that the “Godless Commies” would not be above risking a pilot in a substandard spacecraft if it meant getting there first.

Largely at the instigation of von Braun, now back in Government service as the DRA’s top rocket specialist, a new test plan was put forward. To ensure that the first man in space was an American whilst minimising risks, von Braun proposed launching Mercury on a Redstone for a suborbital mission first. Two spare Redstone missiles had been ordered as part of the early test phase in case of failure of one of the unmanned tests, and true to form von Braun had ensured these extra boosters had been stored rather than scrapped following the completion of those tests. Taking one out of storage and prepping it for flight would be the work of a few weeks, much simpler than the reconditioning job that had been needed for Explorer 1. Although the entire flight would last just over 15 minutes, it would be able to launch on very short notice, whilst the reduced duration and “Fail-safe” assurance that the capsule would return to Earth no matter what meant that the risks of mechanical failure were vastly reduced. Of course a sub-orbital flight would not grab the same headlines as an orbital mission, but by taking the place of one of the planned “Astrochimp” tests the addition of this ballistic hop would have only a small impact on the orbital mission’s schedule. The Air Force, von Braun promised, would be able to have their cake and eat it.

The plan was formally approved in mid-September, by which time Mary-Ann had splashed down after becoming the second chimpanzee in space and the first to orbit the Earth. The next launch, scheduled for 5th October, was chosen to carry the first human in history to travel beyond Earth’s atmosphere.