After achieving President Muskie's goal of sending a man around the Moon, what's next for the US space programme? Let's find out in...

Part IV Post#3: America Decides

In 1976 the United States presented the appearance of having two, parallel manned space programmes. The reality was closer to one-and-a-half, given the significant role of the Air Force in supporting NACAA’s Columbia flights (not least her astronauts and ground support infrastructure), but the public perception was of one Civilian and one Military space programme.

The civilian NACAA was nominally responsible for the Columbia circumlunar project, and by 1976 was already proposing options to build upon the initial achievements with an expansive “Columbia Applications Program”. The CAP was instigated by Edgar Cortright shortly after his appointment as NACAA Chairman in 1973, as a means of ensuring the large amounts of funding being allocated for Columbia didn’t evaporate as soon as Muskie’s target was met. When the first draft report landed on Cortright’s desk in the summer of 1975, it consisted of a veritable Christmas list of programmes that would see the Columbia capsule form the basis of a large space-based manned infrastructure.

The central proposal was, of course, the development of a lunar landing capability to enable Columbia to complete the “final mile” to the lunar surface, now so tantalisingly close. As with von Braun and Faget’s earlier studies, the engineers’ initial preference was for development of a new super-heavy booster to loft a single-short, direct lunar landing vehicle to the surface of the Moon. However, they were well aware of the problems encountered by earlier Direct Ascent studies, and so instead proposed a two-launch approach, based around the existing Minerva B, using a separately launched Descent/Ascent module with which the Columbia Command and Service Module would rendezvous in lunar orbit. The astronauts would dock and transfer across, leaving Columbia unoccupied as they travelled to the surface. This mission mode obviously carried some extra risk, relying as it did upon two separate docking manoeuvres and the ability of Columbia to operate in an unmanned mode, but it would be possible without the need to develop a large new rocket. As such, those funds saved could be ploughed into the rest of the CAP options. These included a “ferry” version of Columbia for use with a series of Starlab-like NACAA Earth orbit and lunar orbit space stations, and an Earth-Moon Lagrange-point modular space station that would act as a gateway to further lunar and interplanetary missions.

Meanwhile, following the post-

Rhene return to flight with DS-23 in August 1974, the USAF continued to fly two-to-three Dynasoar missions per year, including DEL missions. The Starlab space station remained in orbit, but the DS-24/Starlab-3 mission of April 1975 found a station plagued by minor breakdowns and suffering an unfortunate outbreak of mould growing on the walls. Although engineers on the ground were delighted with the data obtained on the long-term performance (or not) of their systems and materials, Lee Gentry’s crew found the experience grueling, and following the recommendations of the Flight Surgeon at Vandenberg they ended the mission early, after just four days on-orbit. Using propellant transferred from

Athena during the mission, the station was reboosted the following week to prolong its orbital life, but soon afterwards the Air Force declared Starlab officially retired from active service.

Following Starlab’s retirement, there was naturally much speculation over a successor station, but in truth few within the service, right up to the Secretary of the Air Force, saw a pressing need. Starlab had demonstrated no key benefit to a manned station, and 90% of any missions that might be of interest could be met far more flexibly by individual DEL or Dynasoar Mk.I flights. The Air Force Research Lab (AFRL), with support from NACAA, continued to push for a replacement to advance understanding of the physiological effects of long-term spaceflight, as well as investigations of in-space manufacturing and perhaps the use of a manned base to support satellite repair and maintenance, but theirs was a quiet voice in a vacuum of indifference. Air Force Space Command as a whole had a far more urgent matter to resolve.

That urgent matter was the Shuttlecraft. Even as Boeing were assembling the Mk.I glider

Tara to replace

Rhene, the Air Force were looking into a successor system for their pioneering spaceplanes. Following the experience gained with Dynasoar, Space Command placed the emphasis for the new Shuttlecraft upon short preparation times, reduced ground support requirements and rapid turnaround. In comparison to its predecessor, much less weight was placed upon cross-range capability, a key design driver for Dynasoar that in practice had never been needed. A crew of at least two was considered desirable, but perhaps the most important requirement was an expansion of down-mass capability. The Air Force had found the Dynasoar Mk.I’s cargo bay to be extremely useful in allowing flexible payload deployment and return, but it was too small for many of the missions they wished to fly. Alternatively, the Dynasoar Experimental Lab attached to the Mk.II gave more room and capabilities, but didn’t permit the return of expensive equipment for re-use. What they wanted was to find the happy medium, a craft with a payload bay sized between the Mk.I and DEL, but which could return its entire cargo to Earth.

Beyond those directly operating and maintaining the Air Force space programme, there was a wider concern that this payload range would not be large enough. Within both the Air Force and the National Reconnaissance Office, there were forces pushing for the Shuttlecraft to be not just an operational recon asset, but a multi-user “space truck”, providing an alternative to the expensive, disposable Minerva with a reusable launcher capable of carrying all critical national security payloads. This group was less concerned with the down-mass capability than in maximising the up-mass whilst minimising costs, and garnered considerable support from those both within the Air Force and Congress who considered America’s reliance upon Minerva as its sole heavy space launcher to be a worrying concentration of eggs in a single basket. To meet this aim, this “Spacelift Faction” wanted the Shuttlecraft to carry not the 2-3 tonnes envisaged by the “Operational Faction”, but closer to the 20 tonnes currently provided by Minerva-B22, which would replace the concepts for a new expendable launcher that were also being considered at the time. This fundamental split over the basic role of the Shuttlecraft led to wildly diverging concepts being put forward when study contracts were awarded to industry in 1974.

By 1976, as the detailed analysis within the Air Force continued, it was becoming clear that the Operations Faction was gradually winning out for one key reason: cost. The benefits of the giant two-stage Space Truck concept being pushed by the Spacelift Faction, best represented by North American’s proposal, relied upon amortising the development and maintenance costs over a large number of missions. However, the size and complexity of the proposed concepts inevitably drove these costs up, to the point where flight rates would have to be on the order of once per week to be competitive. Efforts to downplay the number of man-hours that would be needed between missions were greeted with a sceptical eye following the experience with Dynasoar, whose maintenance costs were three or four times what had been anticipated before going operational. The development costs were also questioned, especially for key components such as the all-new ceramic heat shield technology that would have to be developed, the Truck being far too massive to allow for use of a metallic shield as on Dynasoar. The large, reusable hydrogen-oxygen engines needed to power both stages were also considered high-risk, well beyond the current state-of-the-art. The Spacelift Faction tried to make a virtue of this, promoting their design as a way of encouraging the development of new technologies, but it was an uphill battle. This was especially true given the promising results of the “Future Expendable Launch Vehicle” studies that the Air Force had been pursuing in parallel, which gave a number of options for an expendable heavy-lift solution which could be developed far more cheaply than the Shuttlecraft, although with higher projected operating costs.

By comparison, the alternative “Dynasoar-Plus” architecture exemplified by Boeing’s proposal, was far more of an evolutionary development. Under this concept, a winged orbiter, about 20% larger than Dynasoar, would be launched from the back of a carrier aircraft. The carrier could be an all-new plane, or perhaps a modification of a commercial aircraft such as the 747 jetliner that had entered service a few years earlier. The orbiter would take its propellant from a simple, disposable drop-tank, partially sacrificing the concept of reusability in favour of simplifying the overall design. This sacrifice meant the orbiter would be small and light enough to make use of a metallic “hot skin” thermal protection system based on a modest improvement upon that used on Dynasoar. With the large cross-range requirement deleted, it could also make use of far simpler, straight-edge wings rather than deltas - an option unavailable to the Space Truck due to the thermal loads its greater mass would impose. Costs would be lower than for Dynasoar even without an increased sortie rate or improved maintainability simply due to the substitution of the expensive Minerva booster with a relatively conventional carrier aircraft-plus-droptank.

A marketing illustration of Boeing’s “Dynasoar-Plus” proposal for a future air-launched Shuttlecraft.

Both the Air Force and NACAA plans for the future were of course contingent upon support from the government, which following the 1974 mid-term elections that had returned a Republican majority to both the House and Senate, was far less easily swayed by the recommendations of the incumbent Democratic administration. Columbia in particular was widely viewed within Congress as an expensive vanity-project, despite NACAA’s efforts to promote the idea of a “trickle-down” of technologies from Columbia into the civilian economy. With the economy contracting and inflation picking up, in the FY-76 budget Congress restricted funding for active development of any aspects of the Columbia Applications Program, and completely blocked the acquisition of additional Columbia spacecraft beyond the initial batch of ten already on order from Lockheed.

In this environment, the March 1976 launch of Sapfir-2 was a godsend for NACAA. After a widespread perception that the US was way out in front in the Moon Race - perhaps the only area in which the US wasn’t in relative decline - the Soviet mission came as a splash of cold water in the face for many. Although it quickly became apparent that the Soviet fly-by was a less capable copy of the Columbia lunar orbit mission profile, it nevertheless panicked Congress into action. For the FY-77 budget, passed in late June 1976, Congress not only approved Muskie’s proposed allocations for NACAA to define a lunar landing architecture that could be implemented by 1981, but also authorised additional funding to start long-lead item procurement for an extra five Columbia capsules - a complete U-turn on their position from the previous year.

In contrast, the Air Force still faced a slight squeeze, although not as severe as that NACAA had faced in 1975, given the still chilly relations with Moscow and the Defense Department’s greater skill at budgetary shell-games. However, they were unable to gain a go-ahead for either of their Shuttlecraft concepts. Both the House and Senate Armed Service Committees indicated a willingness to plan for some kind of future replacement for Dynasoar, but were unhappy at the Air Force’s continued indecision over the basic requirements of such a system. Members of Congress were themselves split over their preferred option, with the result that no decision was taken before the 1976 elections.

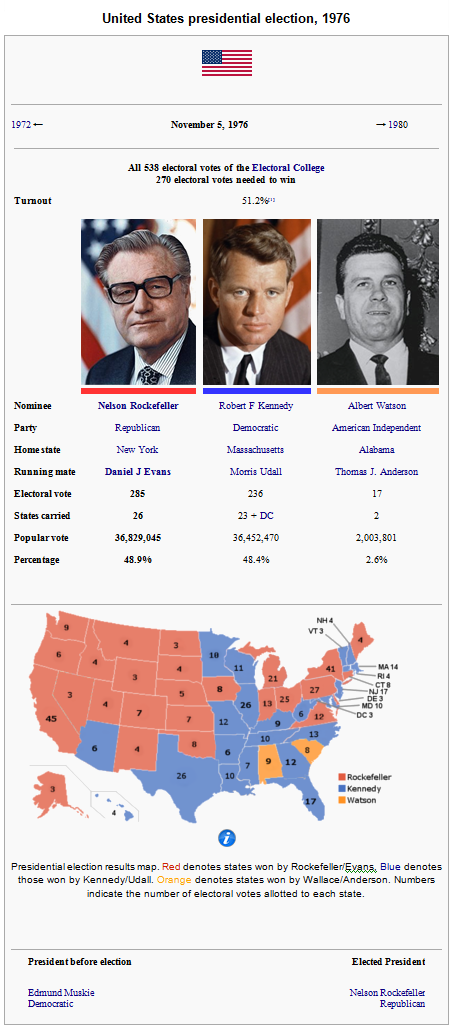

Those elections were to dominate the second half of 1976. After a fractious primary campaign, the Democrats had selected Robert Kennedy as their candidate, with Mo Udall as his running mate. The brother of the failed 1960 presidential candidate and former Ambassador to Eire John Kennedy, “Bobby” had served as Secretary of State during Muskie’s first term as part of a quid-pro-quo for standing aside in the 1968 presidential race. Despite this link, he was seen as the candidate to provide a clean break with the incumbent administration, as his primary opponent was Muskie’s serving Vice President, George McGovern.

Kennedy’s Republican opponent was the Governor of New York, Nelson Rockefeller, who was finally selected at this, his fourth attempt, having previously put himself forward in 1960, 1968 and 1972. Seen as a uniting figure who could swing undecided moderate voters away from the Democrats, Rockefeller and his VP candidate, Daniel J. Evans, projected the image of a no-nonsense, experienced choice to re-build America. Given the unpopularity of Muskie and the Democrats, the Republicans expected a relatively easy win, and didn’t want to spook the centre-ground with a more radical candidate.

As things transpired, the race was a lot closer than many had predicted, with the choice between two northeastern moderate candidates turning a lot of people off. Both men were charismatic, and both were able to deploy considerable personal and family resources to their campaigns. Both were also dogged by some sections of the press with allegations of infidelity, but neither side chose to use this as a weapon against the other, and the stories soon faded into the background. Despite predictions to the contrary, the bicentennial celebrations, including Albert Crews’ and John Kaminski’s successful Columbia-7 mission in September, had very little impact on the campaign. Kennedy was keen to distance himself in the public mind from the incumbent administration, and his decision appeared increasingly wise as the year progressed and “Bicentenary Fatigue” became a growing phenomenon.

In the end, the voters decided narrowly in favour of Rockefeller’s executive experience over Kennedy’s youth and international standing. At just 51.2%, the voter turnout was the lowest for a presidential election since 1948, partly reflecting the apathy many felt at the lack of choice on offer. Rockefeller and Kennedy were virtually neck-a-neck in the popular vote, securing 48.9% and 48.4% respectively, but the electoral college system translated this into a 285-236 victory for Rockefeller, with Alabama and South Carolina returning votes for the American Independent party. The Democrats did receive a consolation prize by regaining control of the Senate, but it was Nelson Rockefeller who was inaugurated as America’s 37th President on 20th January 1977.

As a follow-up to the first Soviet circumlunar mission failed to materialise, and with Columbia-7’s successful mission of September 1976 under their belt, the political momentum for an expansion of the NACAA programme faltered. During the preparation of Rockefeller’s first budget proposal, Chairman Cortright was told to pick from his grand cis-lunar architecture one manned spaceflight option to focus on, or face the prospect of losing all funding for Columbia. Cortright quickly concluded that the lunar landing goal was too long-term, requiring too much development before showing results, to be able to sustain support in Congress.

Cortright did seriously consider a DEL-sized lunar orbit space station, but there were growing concerns over the potential risks of solar radiation in lunar space. 1976 had been a solar minimum year, but as the projected maximum in 1982 got closer, so the odds of a high-intensity solar radiation event during a Columbia mission increased. A lunar station mission lasting several weeks would present a correspondingly larger target, and the prospect of losing a crew to a solar flare was too awful to contemplate. NACAA therefore recommended that their focus for the next few years should be in Earth orbit, using Columbia spacecraft to support a series of civilian space stations that would develop the science and operations skills, as well as preserving the hardware capability, that would be needed for the “horizon goal” of landing a man on the Moon. The Columbia-8, 9 and 10 circumlunar missions already planned would be carried out over the next two years, whilst the five new-build capsules on-order would be adapted for Earth orbital use with a new Starlab-style space station, to be launched by 1979.

This proposal is what appeared in Rockefeller’s budget proposal in Spring 1977, but it immediately came under fire from all sides. Those in Congress who saw the need to expand NACAA’s space activities (led by representatives from Virginia, NACAA’s home state, and Missouri, where McDonnell built the capsules) found the Earth orbit proposals too timid, a step backwards on the road to the lunar surface. On the other side, those who had long opposed Columbia for its association with Muskie, or those who simply felt that manned spaceflight was none of NACAA’s business, were able to point to a duplication of the Air Force’s existing capabilities. The Air Force themselves supported this view, wishing to return manned spaceflight to their exclusive control, even as they internally debated whether manned spaceflight was militarily useful at all.

The end result was a typical political compromise. Columbia would continue to be funded through to Columbia-10, but the contracts for new capsules would be frozen and the remaining funds switched to a Phase-A study on the best, most affordable option for a lunar surface mission (with McDonnell heavily tipped to benefit from these study contracts). At the same time, appropriations were made for the development of the Air Force’s air-launched Shuttlecraft as a replacement for Dynasoar. With the Soviets apparently unable to keep up, there seemed no reason to rush towards a lunar landing. Even at this reduced pace, a manned lunar landing was surely no more than a decade away.