Part I Post #5: Action and Reaction

The reaction of the press all across the Free World to the launch of the planet’s first artificial satellite was a mixture of amazement, pride and a re-enforcement of the image of America as the source of all modern technical marvels. Vanguard 1 (as it had been retrospectively named, the Navy quietly brushing the payloads of earlier, failed attempts under the carpet) was orbiting the Earth once every 133 minutes at a distance of between 650 and 3 800 km. The high apogee meant that, despite its orbital inclination of just over 34 degrees preventing it from directly overflying much of the world’s population (and avoiding potentially provocative overflights of the USSR), it would be on a line of sight with most of the planet at regular intervals. Amateur radio operators immediately rushed to their equipment to pick up Vanguard’s “Beep-beep-beep!”, with the more determined even going so far as to attempt to derive the satellite’s orbital parameters from their own observations. However, after the initial fanfare of the launch, most people quickly incorporated the achievement as part of the backdrop of their lives and moved on to consider more pressing concerns.

The reaction in the Kremlin was not so short-lived. In a short article on page 2,

Pravda congratulated the Americans for their achievement, but warned against “any attempt to extend Imperialism into Cosmic Space." The article went on to reassure readers that “Soviet workers and scientists are even now preparing to launch their own space vehicle in response.” This response was to be made by the R-6, and pressure mounted on Sinilshchikov to get the rocket working. Khrushchev was keen to use a satellite launch to demonstrate how the Soviet Union was catching up with (and would soon surpass) the US, but more importantly he and Ustinov both knew that the Atlas ICBM was nearing completion. The Soviet military was only just starting to come to grips with the nuclear bomber threat; they could not afford to allow a missile gap to develop.

But just one week after Vanguard entered orbit, the Shesterka suffered a second launch failure. This time it was the guidance system at fault, diverting the missile from its programmed course after just 45 seconds of flight, after which the missile was deliberately destroyed as a safety precaution. This second failure in a month was the final nail in Sinilshchikov’s coffin. He was immediately summoned to Moscow and stripped of his role as Chief Designer. He would be replaced at OKB-1 by Vladimir Chelomei, who coincidentally happened to be the boss of Nikita Khrushchev’s son Sergei. This was the realisation of a long-held ambition for Chelomei, and he had many plans for the future of Soviet rocketry, but for now Khrushchev and Ustinov made it very clear that Chelomei had one overriding priority: Get the R-6 flying.

Chelomei set to work immediately. Bringing in many of his own people from OKB-52, he quickly set up an independent review of the R-6 design and production with the aim of identifying and eliminating any flaws that could cause a failure. Over the next month his team produced a slew of recommendations, mostly related to increased redundancy in critical systems, a tighter quality regime at the production facilities, and expanded testing of all systems before and after vehicle integration.

After three months of furious activity, Chelomei was ready to allow Shesterka a third chance to prove itself. On 9th October 1958, an R-6 missile once again stood ready at Launch Complex 1, but this time things would be different. To the delight of the watching Nedelin and the satisfaction of Chelomei the missile made a perfect launch, delivering its dummy warhead to the Kamchatka test site 18 km from the aim point. Or rather, parts of the warhead. It seemed that the sharp-nosed, fast penetration configuration chosen to reduce enemy reaction times was not up to the job of protecting the bomb from the rigours of atmospheric re-entry and instead broke up in mid-air. However, this small detail was kept Top Secret, and TASS was soon announcing that the Soviet Union had developed an ICBM to rival the American Atlas.

The Americans meanwhile were experiencing a few problems of their own. Although the USAF had performed a second successful test launch of the Atlas in August, reaching 2 500 km range, the Navy was having some difficulties in following up the success of Vanguard 1. Another attempt at orbit was made in September, but ended in failure when the second stage burn cut off prematurely, dooming the rocket to a watery grave. Determined to launch a second satellite before the International Geophysical Year ended on 31st December, the NRL engineers focussed all their energy on ensuring success on the next Vanguard. Their hard work paid off, with the flawless launch of Vanguard 2 on 18th December providing an early Christmas present to the team.

Unlike the simple radio beacon payload of Vanguard 1 (which was still operating, powered by its solar cells, four months after launch), the Vanguard 2 satellite would carry a dedicated scientific experiment. Included in the 10 kg mass of the satellite were a pair of small telescopes, facing in opposite directions, at the focus of which was a photocell similar to those that powered the spacecraft. As the satellite spun on its axis, the field of view of the telescopes would sweep past the surface of the Earth, and the reflected sunlight they saw would generate a small current within the photocell. By measuring how the intensity of this current varied, it would be possible to deduce the reflectivity of the clouds, land and sea surface, and so for the first time show the Earth’s percentage of cloud cover from above.

This first experiment in using a satellite to monitor weather was only partly successful. The system relied on the satellite’s spin to give a good field of view, but unfortunately the spin axis achieved was not optimal for the experiment. The system operated for 15 days before a breakdown of the tape recording system ended the flow of data, but for much of that time all that was recorded was starlight. More success was had in the use of Vanguard 2’s radio transmissions to measure ionospheric properties and atmospheric characteristics, adding to the knowledge already being gained from Vanguard 1.

Following the success of Vanguard 2, the Naval Research Laboratory decided to retire the Vanguard project. Although it had opened the Space Age and demonstrated the techniques necessary to reach orbit, its tiny payload capability made it of marginal use for any serious scientific or military purposes. The Navy instead planned to develop a new, more powerful launcher, Explorer, with which they hoped to be able to launch satellites of up to 600 kg. However, this ambition would soon appear far too timid.

Despite the problems with the R-6 warhead (a second test launch in November had also resulted in the re-entry vehicle breaking up), Chelomei felt confident enough in the missile itself to entrust the Shesterka with its secondary mission, that of launching the USSR’s first satellite. Despite Khruschev’s hopes that they could still make the 31st December deadline for the end of the IGY, Chelomei persuaded him that it was better to take a little more time and get it right rather than rush into failure. It was therefore not until the turn of the New Year that the 1 300 kg “Iskusstvennyy Sputnik Zemli Odin” (“Artificial Earth Satellite One”, ISZ-1) was installed at the peak of a Shesterka rocket. In temperatures which dropped below -10 degrees Celsius, the ground crews worked through January to make the launcher ready. With all checks completed, the R-6 was moved to the pad and fuelling commenced on Monday 19th January. After two days of further tests ensured everything was ready, the launch key was turned and the rocket lifted off the pad at 15:03 local time (10:03 UTC). Just as with the previous two launches the Shesterka performed as expected, lofting the satellite, still attached to the Blok-B second stage, into an initial orbit of 185 by 1 768 km.

At this point Chelomei hoped to demonstrate a capability to re-start the Blok-B’s vernier engines, using them to raise the perigee of ISZ-1 by a few hundred kilometers. Unfortunately this proved unsuccessful, with the verniers firing for only a few seconds before shutting down again, raising the orbit by only a dozen kilometres. Chelomei nonetheless considered this to be a qualified success, and shortly afterwards ISZ-1 was separated from its carrier rocket.

Back at the OKB-1 facility in Podlipki, near Moscow, the ISZ-1 control team now took over the mission. Unfortunately, the orientation of the orbit was such that the perigee (the point at which the spacecraft was lowest and therefore moving at its fastest) was over the northern hemisphere, meaning that ISZ-1 was only visible from the control stations at Podlipki, Ulan-Ude and Khabarovsk for periods of three to thirteen minutes at a spell, leaving little time to downlink telemetry or uplink commands. To partially overcome this handicap, ISZ-1 was equipped with a tape recorder which would store all the data collected by its instruments for the previous 105 minute orbit and then play it back at high speed during the brief periods of contact with Ground Control. From these quick bursts, the initial indications were that ‘Object D’ was in perfect health and operating as designed.

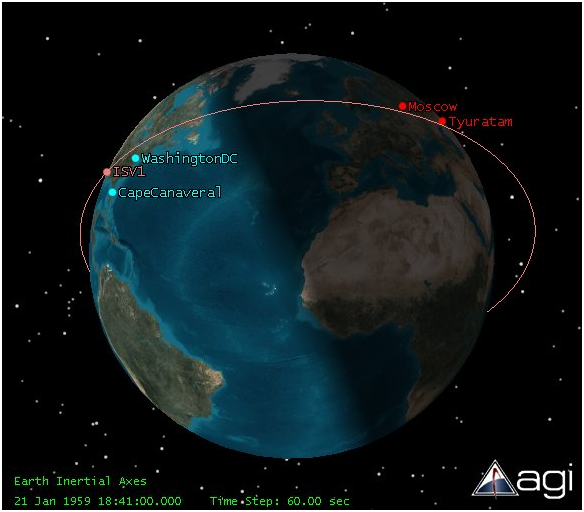

An early period of tension came during Orbit 6, at 18:40 UTC, when ISZ-1’s ground track would for the first time pass directly over the territory of the United States. Unlike the Vanguard launches, Tyuratam’s high latitude meant that it wasn’t possible to craft an orbit that would avoid overflying US airspace. Coincidentally, this first overflight would pass almost directly over Washington DC. How would the Americans react to this intrusion? The Soviet Embassy had alerted the US government of their successful launch within moments of confirmation of the orbit, and American radar and tracking stations were more than capable of spotting the satellite during its previous two orbits, so ISZ-1’s appearance over the Capitol should not come as a complete shock. Even so, there was a nervous atmosphere in Podlipki as technical and military officers packed the control room, despite the late hour, to await contact with the satellite after its first foray over the Imperialist heartland.

First overflight of US territory by ISZ-1, Orbit 6

There were audible sighs of relief from the assembled military brass when contact was re-established on schedule at 22:57 Moscow time (18:57 UTC). The Americans, it seemed, were not going to blow ISZ-1 out of the sky for violating their territory. Then, hard on the heels of relief came exuberance. They would not destroy the satellite because they could not! Soviet spacecraft could cross the United States at will, and there was nothing the Americans could do about it! At 20:26 UTC the satellite ground track again entered US territory, this time over Arizona, and again there was no response. The Americans were impotent before the might of Soviet science!

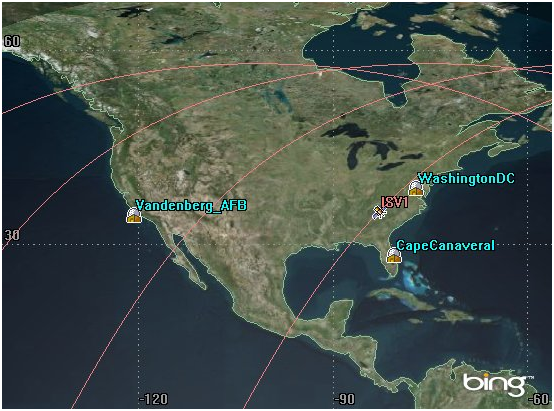

Ground Track of ISZ-1 over North America during Orbits 6-9 (right to left)

Although clearly a vast exaggeration of reality, such feelings were nonetheless also present in some parts of the US military. They had of course known that the Vanguard satellites passed over many nations as a matter of orbital mechanics, and that by adjusting the launch they could easily make a spacecraft overfly the USSR. But to have another power, a hostile power, do the same to the US was… unsettling.

When the news was reported in the paper morning editions and over the radio and television networks, the general public mood was one of surprise. To most Americans, despite their possession of thermonuclear arms, Russia was still perceived as a backward nation of peasant farmers. Now it appeared that they were catching up with the US in technology, and if they could send a satellite over America, why not also a bomb? Government spokesmen emphasised that the US had launched a satellite more than six months before the Soviets, and that even now the Air Force’s Atlas ICBM was entering operation with the 576th Strategic Missile Squadron at Vandenberg Air Force Base, California, keeping America ahead of the Reds in the ability to strike across continents. (The news of the 576th’s establishment came to a surprise to many, including its new CO, who was made aware of his promotion just hours before the press release. He would have to wait a further three months before he received any missiles to command). These arguments were largely accepted by the public, but beneath the general confidence that America was still Number 1, there remained a sense of mild unease and vulnerability throughout the nation.

In contrast to this general mood of concern, a small smile reportedly passed President Eisenhower’s features as he received news of the Soviet launch. He had long been made aware that the Soviets were getting close to launching a satellite, and his reaction to it finally happening was similar to his opinion of the earlier US achievement: It was a neat scientific trick, but nothing to get excited about. As far as Eisenhower was concerned, the most important aspect of ISZ-1 was the precedent it set for overflights. Ever since his 1955 meeting with Premier Bulganin in Geneva, Eisenhower had been trying to establish a principle of “Open Skies” that would allow the assets of one Superpower to overfly the territory of the other on reconnaissance missions without it being seen as reason for an immediate escalation to war, as a means of ensuring no secret military build-ups could take place. At that time and ever since, the Soviets had flatly refused such a proposal, but now that the Soviets had overflown the US with their satellite they could hardly object to the Americans returning the favour.

To cement this principle, as well as to confirm American leadership in rocketry, it was necessary for the US to quickly perform an overflight mission of their own. With the recent cancellation of Project Vanguard and the Atlas ICBM still in trials (despite the USAF declaration that the missile was “Operational”), the only near-term option was the Army’s Redstone.

The Army Ballistic Missile Agency had been working on Project Orbiter for several years as a potential back-up to Vanguard, but had been ordered two years earlier to cease all work on space launches. Whilst reluctantly following that command, von Braun had decided that, rather than scrapping the missiles he had, it would be useful to begin a “Long term storage test” of his Jupiter-C vehicle. He had persuaded the Jet Propulsion Lab that such a test would be instructive for their Sergeant upper stage booster as well, meaning that when Defense Secretary Neil McElroy called ABMA commander Major General John Bruce Medaris in January 1959, the Major General was able to confirm that the Jupiter-C and her payload could be made ready to launch within three months of the President’s say-so. The word was given, and so after almost thirty years of dreaming, Wernher von Braun was finally to get his chance to enter the Space Age.