So, after an absence of 18 months or more, I am back posting. Why I hear you ask? Well, I retired in June and am now a gentleman of leisure...and you can only play so much golf, after all. What have I been doing since June? Well, I have modified all my large timelines that I posted on Kindle, Rudolf will Reign, Consequences of an Errant Shell, the Australasian Kingdom, Leyte Gulf Redux and A Reluctant Fuhrer. Proof reading 2500 pages of text can take some time. Plus I have cleaned the house and published a book on the Post Office in Tasmania. And dealt with the usual drama of having children, albeit they are supposed to be adults.

So why I have I posted this when I already had a half commenced timeline? I wanted to make a fresh start, not only on this, but also on two other timelines, one a pre 1900 Australia one, another an Alien Space Bats scenario based on my Errant Shell World where Imperial Russia is still hanging around in 2020?

So, you ask, you intend to write three timelines at once. When I am rolling, which I hope to be now, I have always updated two timelines at once. Three is a bit more of a stretch, so we will see how I go. I don't have those other annoying distractions, such as clients, to take up my time, anymore, so it's virgin ground, so to speak.

Thanks to all those that have read my previous works and hopefully more will jump on board. Anyways, here we go.

0200, Jade estuary, German Empire, 22 June 1916

After the disappointing results of the 31st May, when two out of three ships of the 6th Division had grounded and subsequently fouled their condensers, the operation was cancelled and rescheduled until the 20th June, subsequently amended to the 22nd. It had allowed him to add ships to his order of battle, notably Koenig Albert and the newly completed Bayern, the latter manned by the transfer of the crew from the newly decommissioned old pre dreadnought Lothringen.

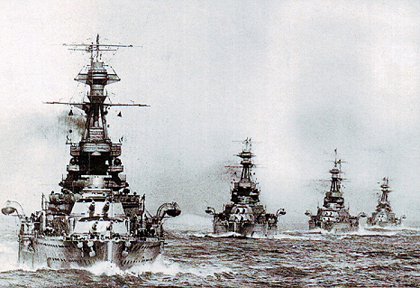

The plan was simple enough. It represented his basic strategy since he had taken over command of the High Seas Fleet in January 1916 from the perennially cautious Hugo von Pohl. Scheer was aware that he could not match the Grand Fleet for sheer numbers, even taking into consideration British naval deployments in the Mediterranean. With the Baltic activities of the Russians curtailed, Scheer had gathered as much of the High Seas Fleet as possible for the operation, in an attempt to draw forth and trap part of the Grand Fleet and destroy it comprehensively, namely David Beatty's battlecruiser force; hopefully the Harwich Force as well.

The unfortunate cancellation of the May operation due to two ships grounding and fouling their condensers meant the submarine forces available to lie off major British bases were not as they had been a month ago, but the plan was unchanged. Hipper had already sortied at 0030 with the 1st and 2nd Scouting Groups, consisting of five battle-cruisers, four light cruisers and 32 torpedo boats.

They were to bombard Sunderland and draw David Beatty's battle-cruiser force South from the Firth of Forth. Hipper would then to lead the battle-cruiser force back onto the guns of Scheer's High Seas Fleet, waiting 45-50 miles off Flanborough Head. He had originally counted on Zeppelin intelligence; however, June 1916 had been a month of extremely poor summer weather, with a maximum four days running at 8 degrees Celsius in Hamburg. Forecast for the day was modest, with gusting winds, all of which would hamper zeppelin operations.

The last month had not been a kind one for the Central Powers, Russia destroying Austro-Hungary's armies in Galicia and the Ottomans also in retreat in the East. A victory was badly needed. For that reason alone, Scheer had pulled together as much fighting power as possible. After Hipper drew the British scouting forces South, they would be confronted with 18 dreadnoughts, seven pre dreadnoughts, an armoured cruiser, 13 light cruisers and 49 torpedo boats.

This had been the original plan, however, with zeppelin reconnaissance not a possibility, Scheer had amended it to encompass Hipper's forces converging on the Skagerrak, engaging and destroying any commerce and Royal Navy patrols that frequented the area. He was hopeful this would lure part of the British fleet out to drive his forces away. The High Seas Fleet could then overwhelm this under gunned force in waters much closer to home, their flanks covered by light forces and their relatively short path to retreat assured. In all total forces were:

1. Battlecruiser force, Vice Admiral Franz von Hipper

I Scouting Group

Vizeadmiral Franz von Hipper, 1. Admiralstabsoffizier Korvettenkapitän Erich Raeder

SMS Lützow, flag, Vizeadmiral Franz von Hipper, Kapitän zur See Harder

SMS Derflinger, Kapitän zur See Hartog

SMS Seydlitz, Kapitän zur See von Egidy

SMS Moltke, Kapitän zur See Harpf

SMS von der Tann, Kapitän zur See Zenker

IXth Flotilla

V 28, Kapitänleutnant Lenßen hoisting Korvettenkapitän Goehle (Flottila-Leader) - screening 1SG

IXth Flotilla, 17th Half Flotilla, V27, V28, V26, S36, S51, S52

IXth Flotilla, 18th Half Flotilla

V30, Oberleutnant zur See Ernst Wolf hoisting Korvettenkapitän Werner Tillessen (flag), S34, S33, V29, S35, V30

II Scouting Group

Konteradmiral F. Boedicker

SMS Frankfurt, Kapitän zur See Thilo von Trotha hoisting Konteradmiral F. Boedicker (flag)

SMS Pillau, Fregattenkapitän Konrad Mommsen

SMS Elbing, Fregattenkapitän Madlung

SMS Wiesbaden, Fregattenkapitän Reiß

IInd Flotilla

B98, Kapitänleutnant Theodor Hengstenberg hoisting Fregattenkapitän Schuur (flag)

IInd Flotilla, 3rd Half Flotilla

Korvettenkapitän Boest (flag) on B 98, B98, G101, G102, B112, B97, S49, V43

IInd Flotilla, 4th Half Flotilla

Korvettenkapitän Dithmar (flag) on B 109, B109, B110, B111, G103, G104

VIth Flotilla

G41 Kapitänleutnant Hermann Boehm hoisting Korvettenkapitän Max Schultz (flag)

VIth Flotilla, 11th Half Flotilla, Kapitänleutnant Wilhelm Rümann on G 41, G41, V44, G87, G86

VIth Flotilla, 12th Half Flotilla

V69, Kapitänleutnant Stecher hoisting Kapitänleutnant Lahs (flag), V69, V45, V46, S50, G37

2. High Seas Fleet, Main Body

Chef der Hochseestreitkräfte:Vizeadmiral Reinhard Scheer

Chef des Stabes: Kapitän zur See Adolf von Trotha

Chef der Operationsabteilung: Kapitän zur See von Levezow

IIIrd Squadron, 5th Division

Konteradmiral Paul Behncke, 1. Admiralstabsoffizier Korvettenkapitän Freiherr von Sagern

SMS König flag, Kapitän zur See Brüninghaus

SMS Grosser Kurfürst, Kapitän zur See Goette

SMS Markgraf, Kapitän zur See Seiferling

SMS Kronprinz, Kapitän zur See Konstanz Feldt

IIIrd Squadron, 6th Division

Konteradmiral H. Nordmann (2nd Admiral of IIIrd Squadron)

SMS Kaiser, flag, Konteradmiral H. Nordmann, Kapitän zur See Freiherr von Keyserlingk

SMS Prinzregent Luitpold, Kapitän zur See Heuser

SMS Koenig Albert, Kapitän zur See Gaskell

SMS Kaiserin, Kapitän zur See Sievers

SMS Friedrich der Große, Kapitän zur See Theodor Fuchs

Flottenflaggschiff: SMS Bayern, Kapitän zur See Max Hahn(not in squadron or divisional organisation)

Ist Squadron, 1st Division

Vizeadmiral E. Schmidt, 1. Admiralstabsoffizier Korvettenkapitän Wolfgang Wegener

SMS Ostfriesland flag, Vizeadmiral Schmidt, Kapitän zur See von Natzmer

SMS Thüringen, Kapitän zur See Hans Küsel

SMS Helgoland, Kapitän zur See von Kamecke

SMS Oldenburg, Kapitän zur See Höpfner

Ist Squadron, 2nd Division

Konteradmiral W. Engelhart (2nd Admiral of Ist Squadron)

SMS Posen, flag, Konteradmiral Engelhart, Kapitän zur See Richard Lange

SMS Rheinland, Kapitän zur See Rohardt

SMS Nassau, Kapitän zur See von Schlee

SMS Westfalen, Kapitän zur See Redlich

Vth Scouting Group

Kommodore L. von Reuter, Admiralstabsoffizier Korvettenkapitän Heinrich Weber

SMS Stettin, Fregattenkapitän Friedrich Rebensburg

SMS Stuttgart, Fregattenkapitän Hagedorn

SMS Graudenz, Fregattenkapitän von Steiglitz

SMS Straslund, Fregattenkapitän Boller

SMS Brummer, Fregattenkapitän Drygala

IInd Squadron

Konteradmiral F. Mauve

IInd Squadron, 3rd Division

Konteradmiral Mauve, 1. Admiralstabsoffizier Korvettenkapitän Kahlert

SMS Deutschland, flag, Konteradmiral Mauve, Kapitän zur See Meurer

SMS Pommern, Kapitän zur See Bölken

SMS Pruessen, Kapitän zur See Lammers

SMS Schlesien, Kapitän zur See Fr. Behncke

IInd Squadron, IVth Division

Konteradmiral Freiherr F. von Dalwigk zu Lichtenfels (2nd Admiral of IInd Squadron)

SMS Schleswig-Holstein, Kapitän zur See Barrentrapp

SMS Hessen, Kapitän zur See Bartels

SMS Hannover, flag, Konteradmiral Baron von Dalwigk zu Lichtenfels, Kapitän zur See Wilhelm Heine

SMS Roon, Kapitän zur See Wilhelm von Karpf

IVth Scouting Group

SMS München, Korvettenkapitän Oscar Böcker

SMS Frauenlob, Fregattenkapitän Georg Hoffman

SMS Berlin, Fregattenkapitän Hahn

SMS Lubeck, Fregattenkapitän Priilowitz

SMS Danzig, Fregattenkapitän Wagner

Attached IVth Scouting Group

SMS Hamburg, Kapitän zur SeeBauer, Leader of Submarines

1st Leader of Destroyers

Kommodore A. Michelsen, Admiralstabsoffizier Korvettenkapitän Junkermann

SMS Rostock, Kommodore A. Michelsen, Fregattenkapitän Otto Feldmann

2nd Leader of Destroyers

Kommodore P. Heinrich, Admiralstabsoffizier Kapitänleutnant Meier

SMS Regensburg, Kommodore P. Heinrich, Fregattenkapitän Heuberer

Ist Flotilla, 1st Half Flotilla

Kapitänleutnant Conrad Albrecht (flag) on G39, G38, G39, G40, S32, V170, G197

Ist Flotilla, 2nd Half Flotilla

G192, G195, G196, G193

IIIrd Flotilla

S53, Kapitänleutnant Friedrich Götting hoisting Korvettenkapitän Hollman (flag)

IIIrd Flotilla, 5th Half Flotilla, V71, V73, G88, V74, V70

IIIrd Flotilla, 6th Half Flotilla

Kapitänleutnant Fröhlich, S54, V48, G42, G85, S55

Vth Flotilla

G11, Kapitänleutnant Adolf Müller hosting Korvettenkapitän Heinecke (flag)

Vth Flotilla, 9th Half Flotilla

Kapitänleutnant von Pohl, V2, V4, V6, V1, V3

Vth Flotilla, 10th Half Flotilla

G8, Oberleutnant zur See Rodenberg hosting KapitänleutnantFriedrich Klein, G7, V5, G9, G10, G8

VIIth Flotilla

S24 Kapitänleutnant Fink hoisting Korvettenkapitän von Koch (flag)

VIIth Flotilla, 13th Half Flotilla

Kapitänleutnant G. von Zitzewitz on S15, S15, S17, S20, S16, S18, S24

VIIth Flotilla, 14th Half Flotilla

Korvettenkapitän Hermann Cordes

S19, Oberleutnant zur See Reimer hoisting Korvettenkapitän Hermann Cordes, S19, S23, V189, V186

XIth Flotilla, 21st Half Flotilla

Kapitänleutnant G. von Bulow on S59, S59, S58, S57, G89, G90

XIth Flotilla, 22nd Half Flotilla

Korvettenkapitän H.Curnow, V75, V76, V77, V78

In all, it represented five battle-cruisers, 18 dreadnoughts, seven pre dreadnoughts, one armoured cruiser, 17 light cruisers and 81 torpedo boats, all of the High Seas Fleet's strength, 119 ships of war.

So why I have I posted this when I already had a half commenced timeline? I wanted to make a fresh start, not only on this, but also on two other timelines, one a pre 1900 Australia one, another an Alien Space Bats scenario based on my Errant Shell World where Imperial Russia is still hanging around in 2020?

So, you ask, you intend to write three timelines at once. When I am rolling, which I hope to be now, I have always updated two timelines at once. Three is a bit more of a stretch, so we will see how I go. I don't have those other annoying distractions, such as clients, to take up my time, anymore, so it's virgin ground, so to speak.

Thanks to all those that have read my previous works and hopefully more will jump on board. Anyways, here we go.

0200, Jade estuary, German Empire, 22 June 1916

After the disappointing results of the 31st May, when two out of three ships of the 6th Division had grounded and subsequently fouled their condensers, the operation was cancelled and rescheduled until the 20th June, subsequently amended to the 22nd. It had allowed him to add ships to his order of battle, notably Koenig Albert and the newly completed Bayern, the latter manned by the transfer of the crew from the newly decommissioned old pre dreadnought Lothringen.

The plan was simple enough. It represented his basic strategy since he had taken over command of the High Seas Fleet in January 1916 from the perennially cautious Hugo von Pohl. Scheer was aware that he could not match the Grand Fleet for sheer numbers, even taking into consideration British naval deployments in the Mediterranean. With the Baltic activities of the Russians curtailed, Scheer had gathered as much of the High Seas Fleet as possible for the operation, in an attempt to draw forth and trap part of the Grand Fleet and destroy it comprehensively, namely David Beatty's battlecruiser force; hopefully the Harwich Force as well.

The unfortunate cancellation of the May operation due to two ships grounding and fouling their condensers meant the submarine forces available to lie off major British bases were not as they had been a month ago, but the plan was unchanged. Hipper had already sortied at 0030 with the 1st and 2nd Scouting Groups, consisting of five battle-cruisers, four light cruisers and 32 torpedo boats.

They were to bombard Sunderland and draw David Beatty's battle-cruiser force South from the Firth of Forth. Hipper would then to lead the battle-cruiser force back onto the guns of Scheer's High Seas Fleet, waiting 45-50 miles off Flanborough Head. He had originally counted on Zeppelin intelligence; however, June 1916 had been a month of extremely poor summer weather, with a maximum four days running at 8 degrees Celsius in Hamburg. Forecast for the day was modest, with gusting winds, all of which would hamper zeppelin operations.

The last month had not been a kind one for the Central Powers, Russia destroying Austro-Hungary's armies in Galicia and the Ottomans also in retreat in the East. A victory was badly needed. For that reason alone, Scheer had pulled together as much fighting power as possible. After Hipper drew the British scouting forces South, they would be confronted with 18 dreadnoughts, seven pre dreadnoughts, an armoured cruiser, 13 light cruisers and 49 torpedo boats.

This had been the original plan, however, with zeppelin reconnaissance not a possibility, Scheer had amended it to encompass Hipper's forces converging on the Skagerrak, engaging and destroying any commerce and Royal Navy patrols that frequented the area. He was hopeful this would lure part of the British fleet out to drive his forces away. The High Seas Fleet could then overwhelm this under gunned force in waters much closer to home, their flanks covered by light forces and their relatively short path to retreat assured. In all total forces were:

1. Battlecruiser force, Vice Admiral Franz von Hipper

I Scouting Group

Vizeadmiral Franz von Hipper, 1. Admiralstabsoffizier Korvettenkapitän Erich Raeder

SMS Lützow, flag, Vizeadmiral Franz von Hipper, Kapitän zur See Harder

SMS Derflinger, Kapitän zur See Hartog

SMS Seydlitz, Kapitän zur See von Egidy

SMS Moltke, Kapitän zur See Harpf

SMS von der Tann, Kapitän zur See Zenker

IXth Flotilla

V 28, Kapitänleutnant Lenßen hoisting Korvettenkapitän Goehle (Flottila-Leader) - screening 1SG

IXth Flotilla, 17th Half Flotilla, V27, V28, V26, S36, S51, S52

IXth Flotilla, 18th Half Flotilla

V30, Oberleutnant zur See Ernst Wolf hoisting Korvettenkapitän Werner Tillessen (flag), S34, S33, V29, S35, V30

II Scouting Group

Konteradmiral F. Boedicker

SMS Frankfurt, Kapitän zur See Thilo von Trotha hoisting Konteradmiral F. Boedicker (flag)

SMS Pillau, Fregattenkapitän Konrad Mommsen

SMS Elbing, Fregattenkapitän Madlung

SMS Wiesbaden, Fregattenkapitän Reiß

IInd Flotilla

B98, Kapitänleutnant Theodor Hengstenberg hoisting Fregattenkapitän Schuur (flag)

IInd Flotilla, 3rd Half Flotilla

Korvettenkapitän Boest (flag) on B 98, B98, G101, G102, B112, B97, S49, V43

IInd Flotilla, 4th Half Flotilla

Korvettenkapitän Dithmar (flag) on B 109, B109, B110, B111, G103, G104

VIth Flotilla

G41 Kapitänleutnant Hermann Boehm hoisting Korvettenkapitän Max Schultz (flag)

VIth Flotilla, 11th Half Flotilla, Kapitänleutnant Wilhelm Rümann on G 41, G41, V44, G87, G86

VIth Flotilla, 12th Half Flotilla

V69, Kapitänleutnant Stecher hoisting Kapitänleutnant Lahs (flag), V69, V45, V46, S50, G37

2. High Seas Fleet, Main Body

Chef der Hochseestreitkräfte:Vizeadmiral Reinhard Scheer

Chef des Stabes: Kapitän zur See Adolf von Trotha

Chef der Operationsabteilung: Kapitän zur See von Levezow

IIIrd Squadron, 5th Division

Konteradmiral Paul Behncke, 1. Admiralstabsoffizier Korvettenkapitän Freiherr von Sagern

SMS König flag, Kapitän zur See Brüninghaus

SMS Grosser Kurfürst, Kapitän zur See Goette

SMS Markgraf, Kapitän zur See Seiferling

SMS Kronprinz, Kapitän zur See Konstanz Feldt

IIIrd Squadron, 6th Division

Konteradmiral H. Nordmann (2nd Admiral of IIIrd Squadron)

SMS Kaiser, flag, Konteradmiral H. Nordmann, Kapitän zur See Freiherr von Keyserlingk

SMS Prinzregent Luitpold, Kapitän zur See Heuser

SMS Koenig Albert, Kapitän zur See Gaskell

SMS Kaiserin, Kapitän zur See Sievers

SMS Friedrich der Große, Kapitän zur See Theodor Fuchs

Flottenflaggschiff: SMS Bayern, Kapitän zur See Max Hahn(not in squadron or divisional organisation)

Ist Squadron, 1st Division

Vizeadmiral E. Schmidt, 1. Admiralstabsoffizier Korvettenkapitän Wolfgang Wegener

SMS Ostfriesland flag, Vizeadmiral Schmidt, Kapitän zur See von Natzmer

SMS Thüringen, Kapitän zur See Hans Küsel

SMS Helgoland, Kapitän zur See von Kamecke

SMS Oldenburg, Kapitän zur See Höpfner

Ist Squadron, 2nd Division

Konteradmiral W. Engelhart (2nd Admiral of Ist Squadron)

SMS Posen, flag, Konteradmiral Engelhart, Kapitän zur See Richard Lange

SMS Rheinland, Kapitän zur See Rohardt

SMS Nassau, Kapitän zur See von Schlee

SMS Westfalen, Kapitän zur See Redlich

Vth Scouting Group

Kommodore L. von Reuter, Admiralstabsoffizier Korvettenkapitän Heinrich Weber

SMS Stettin, Fregattenkapitän Friedrich Rebensburg

SMS Stuttgart, Fregattenkapitän Hagedorn

SMS Graudenz, Fregattenkapitän von Steiglitz

SMS Straslund, Fregattenkapitän Boller

SMS Brummer, Fregattenkapitän Drygala

IInd Squadron

Konteradmiral F. Mauve

IInd Squadron, 3rd Division

Konteradmiral Mauve, 1. Admiralstabsoffizier Korvettenkapitän Kahlert

SMS Deutschland, flag, Konteradmiral Mauve, Kapitän zur See Meurer

SMS Pommern, Kapitän zur See Bölken

SMS Pruessen, Kapitän zur See Lammers

SMS Schlesien, Kapitän zur See Fr. Behncke

IInd Squadron, IVth Division

Konteradmiral Freiherr F. von Dalwigk zu Lichtenfels (2nd Admiral of IInd Squadron)

SMS Schleswig-Holstein, Kapitän zur See Barrentrapp

SMS Hessen, Kapitän zur See Bartels

SMS Hannover, flag, Konteradmiral Baron von Dalwigk zu Lichtenfels, Kapitän zur See Wilhelm Heine

SMS Roon, Kapitän zur See Wilhelm von Karpf

IVth Scouting Group

SMS München, Korvettenkapitän Oscar Böcker

SMS Frauenlob, Fregattenkapitän Georg Hoffman

SMS Berlin, Fregattenkapitän Hahn

SMS Lubeck, Fregattenkapitän Priilowitz

SMS Danzig, Fregattenkapitän Wagner

Attached IVth Scouting Group

SMS Hamburg, Kapitän zur SeeBauer, Leader of Submarines

1st Leader of Destroyers

Kommodore A. Michelsen, Admiralstabsoffizier Korvettenkapitän Junkermann

SMS Rostock, Kommodore A. Michelsen, Fregattenkapitän Otto Feldmann

2nd Leader of Destroyers

Kommodore P. Heinrich, Admiralstabsoffizier Kapitänleutnant Meier

SMS Regensburg, Kommodore P. Heinrich, Fregattenkapitän Heuberer

Ist Flotilla, 1st Half Flotilla

Kapitänleutnant Conrad Albrecht (flag) on G39, G38, G39, G40, S32, V170, G197

Ist Flotilla, 2nd Half Flotilla

G192, G195, G196, G193

IIIrd Flotilla

S53, Kapitänleutnant Friedrich Götting hoisting Korvettenkapitän Hollman (flag)

IIIrd Flotilla, 5th Half Flotilla, V71, V73, G88, V74, V70

IIIrd Flotilla, 6th Half Flotilla

Kapitänleutnant Fröhlich, S54, V48, G42, G85, S55

Vth Flotilla

G11, Kapitänleutnant Adolf Müller hosting Korvettenkapitän Heinecke (flag)

Vth Flotilla, 9th Half Flotilla

Kapitänleutnant von Pohl, V2, V4, V6, V1, V3

Vth Flotilla, 10th Half Flotilla

G8, Oberleutnant zur See Rodenberg hosting KapitänleutnantFriedrich Klein, G7, V5, G9, G10, G8

VIIth Flotilla

S24 Kapitänleutnant Fink hoisting Korvettenkapitän von Koch (flag)

VIIth Flotilla, 13th Half Flotilla

Kapitänleutnant G. von Zitzewitz on S15, S15, S17, S20, S16, S18, S24

VIIth Flotilla, 14th Half Flotilla

Korvettenkapitän Hermann Cordes

S19, Oberleutnant zur See Reimer hoisting Korvettenkapitän Hermann Cordes, S19, S23, V189, V186

XIth Flotilla, 21st Half Flotilla

Kapitänleutnant G. von Bulow on S59, S59, S58, S57, G89, G90

XIth Flotilla, 22nd Half Flotilla

Korvettenkapitän H.Curnow, V75, V76, V77, V78

In all, it represented five battle-cruisers, 18 dreadnoughts, seven pre dreadnoughts, one armoured cruiser, 17 light cruisers and 81 torpedo boats, all of the High Seas Fleet's strength, 119 ships of war.

Last edited: