Patience mate - it was updated in January.Just asking if ever this will be continued at all or just Plain Abondoned????

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

It's A Long Way To Nagasaki: The Anglo-Japanese War

- Thread starter SealTheRealDeal

- Start date

There may be an update soon, school is easing off.Just asking if ever this will be continued at all or just Plain Abondoned????

Stop.Just asking if ever this will be continued at all or just Plain Abondoned????

You've done this twice TODAY.

Updates will be posted when/if authors have them ready.

raharris1973

Gone Fishin'

This is a great timeline, easy to suspend disbelief, and well-told.

I find your use of Canadians and Australians as substitutes for the Americans in Southwest Pacific fighting to be very interesting. I presume there's been substantial British fleet support to enable the troop deployments and secure SLOCs beyond the immediate battle zone.

Will there be any exploration of economic and budgetary effects on Britain and the Dominions?

I imagine fighting this logistics heavy war at such a distance will be ruinously expensive for the British Empire and Dominion budgets and blow a hole through their foreign reserves and make the prospect of later fighting or rivalry with Germany or the USSR look nightmarish. Will London confess that to either the French or the Americans?

In Canada and Australia, I imagine the war effort, both the enlistments, and the supporting production, will bring the countries to about zero employment. Indeed, I wouldn't be surprised if Canadian labor agents don't start trying to recruit in the US just over the border, the US deep south, British West Indies, and Mexico to fill some production and agriculture jobs during wartime.

Despite the British Empire focus, I like that you've provided decent snapshots of the China front and the Soviet Far East and DEI. One question though. Will we see more British-Chinese military cooperation develop? I can think of a few potential areas - longer-range RAF bombers staging from Chinese territories, RN subs attacking traffic on the China coast, and the British delivering higher caliber artillery tubes to the Chinese to raise their firepower game.

Well done, and looking forward to future installments!

I find your use of Canadians and Australians as substitutes for the Americans in Southwest Pacific fighting to be very interesting. I presume there's been substantial British fleet support to enable the troop deployments and secure SLOCs beyond the immediate battle zone.

Will there be any exploration of economic and budgetary effects on Britain and the Dominions?

I imagine fighting this logistics heavy war at such a distance will be ruinously expensive for the British Empire and Dominion budgets and blow a hole through their foreign reserves and make the prospect of later fighting or rivalry with Germany or the USSR look nightmarish. Will London confess that to either the French or the Americans?

In Canada and Australia, I imagine the war effort, both the enlistments, and the supporting production, will bring the countries to about zero employment. Indeed, I wouldn't be surprised if Canadian labor agents don't start trying to recruit in the US just over the border, the US deep south, British West Indies, and Mexico to fill some production and agriculture jobs during wartime.

Despite the British Empire focus, I like that you've provided decent snapshots of the China front and the Soviet Far East and DEI. One question though. Will we see more British-Chinese military cooperation develop? I can think of a few potential areas - longer-range RAF bombers staging from Chinese territories, RN subs attacking traffic on the China coast, and the British delivering higher caliber artillery tubes to the Chinese to raise their firepower game.

Well done, and looking forward to future installments!

Despite the British Empire focus, I like that you've provided decent snapshots of the China front and the Soviet Far East and DEI. One question though. Will we see more British-Chinese military cooperation develop? I can think of a few potential areas - longer-range RAF bombers staging from Chinese territories, RN subs attacking traffic on the China coast, and the British delivering higher caliber artillery tubes to the Chinese to raise their firepower game.

23. Concluding Year 1

The other Downunderers: The Empire Aids Australia

With neither the Canadians nor the Marines following through on the proposed landing in New Guinea envisioned as the culmination of Operation Ball Peen, the Australians were left to go it alone. This is not to say that the Australians had been completely left hanging. The withdrawal of the IJA’s 16th Division had made advancing easy, the RN and RAF finally closing the Japanese supply lines was appreciated, even if perceived to be overdue.

That still left the prickly problem of the 21st Division and the difficulties supplying a campaign to retake the Territory of New Guinea by way of the Territory of Papua. Worse still, the Australian public did not appreciate the extent to which the campaign relied on the Australian Militia.[1] Some sort of additional aid was needed, if only to relieve militia units of their third echelon duties so more boys and men could return to their mothers and wives. So far, the only British deployment had been the 1st Infantry division, and while welcome, more was still needed to release a desirable number of Militia from their support duties on the island.

Thus came the other Southern Divisions to the rescue. The 2nd New Zealand Division, now at nearly full strength,[2] arrived in high spirits following the conclusion of the Borneo Campaign. The 1st South African Infantry Brigade also arrived in late September. At the same time a company of the Rhodesian Regiment arrived and, to the Australians’ confusion, promptly embedded itself in the New Zealanders’ command structure rather than the South Africans’.

This assorted influx would allow for the militia presence to be reduced to a more politically palatable level. If the Imperial and Commonwealth units had come expecting a glorious campaign, they were to be disappointed. General Officer Commanding Thomas Blamey saw to it that Australia’s 6th and 7th Divisions formed the frontline forces, while the Brits, Kiwis, Boers, and Rhodies, at best, performed rear area security.

Ostensibly this was to ensure that Australians secured their own territory, as they were responsible for it. This answer was not necessarily accepted by all. As one South African put it, “We were white coolies tending to the Ozzies’ bruised egos after the Navy okes prioritized Singapore over them.”

Further, there was some contention over exactly how much autonomy Blamey’s Australian GHQ should have from Gort’s Imperial General Staff. For the time being, the continued Australian advance kept official criticism and skepticism to a minimal.

Picking Up Where The Canadians Left Off: The Marines Push to Rabaul

By the 9th of September the last Canadian had departed New Britain. The Royal Marines division that replaced them had a smaller authorized strength, but with how depleted the Canadians had become, the Royal Marines were actually the larger force. Further, with Australian Citizens Forces taking over rear area duties, the Royal Marines’ frontline strength was greater than what the Canadians had first landed on New Britain with. They were in high spirits as they made rapid progress towards Rabaul.

The Imperial Japanese Army on the other hand were feeling the pinch of having their supply line severed by British air power. They had hoped to wipe the Canadians from the island and then sit in place. However, the Canadians’ Hail Mary effort and their replacement by fresh British regulars scuppered that. The choice now was between a Hail Mary effort of their own, or to bunker down and wait for the IJN to open the path for reinforcements. As an IJA man, Lieutenant General Mitsune Ushijima[3] was loath to count on the IJN for anything. But, given the logistical situation and the prior difficulties encountered when trying to assault the Canadian toe holds, the prospects for a successful offensive seemed incredibly slim. Further, as an army engineer by trade, he was one of the few IJA generals who favored earthworks over the bayonet.

In anticipation of the Canadians landing closer to Rabaul than they ended up doing, the Lt. General had a number of defensive works made around the Rabaul Caldera. These efforts were resumed and redoubled after the Canadian break out. Not only was the town surrounded by a network of trenches, but improvements were made to the caves on Mt. Vulcan, Rabalanakaia, and Tavurvur, creating an impromptu bunker network that would be immensely difficult to conquer.

Large calibre shell fire has revealed concrete and and rebar improvements to a natural cave on the Rabaul Caldera.

These construction projects were enabled by the slow pace of the British, which was less an advance and more a total relocation of the base camps established by the Canadians. Driven by his characteristic excess caution, McNaughton had landed pretty much in the middle of nowhere. As a result, the camps at Uvol and Mataburu, and all the picket sites between them, were of no use for sustaining an attack on Rabaul, the actual objective of the campaign.

The new site they selected was to be the coastal hamlet of Vunavilila, one a peninsula about a dozen kilometers west of Rabaul. Naturally, this was an ambitious target. This was a location easily reached by the enemy, meaning that a landing here would fail if the enemy opposed it. The only way to successfully land would be to do so unopposed, and with the Japanese so nearby that seemed rather unlikely.

Unless they could be misdirected.

Vunavilila was a dangerously opportunistic site for a landing, but there was an equally opportunistic target on the opposite side of the Rabaul Caldera. Karavi was a similarly sized coastal settlement about a dozen kilometers southeast of Rabaul, was practically in spitting distance of the Duke of York Islands, which would serve as the jumping off point for the Marines’ landing. If they could telegraph an attack on Karavi, they could potentially land at Vunavilila unopposed and establish a foothold before the Japanese could redeploy against the real landing site.

Throughout September, goods and personnel were moved to Duke of York Island, with no efforts made to disguise the troop movements. On the contrary, conscious efforts were made to accentuate their concentration on the southern shore. Things moved fast as the Royal Marines Division were both primarily light infantry and a binary division, meaning they had little in the way of “tail” to drag around. Within less than a month, “Operation Canadian Thanksgiving” was ready to go. As the clock struck midnight and the 9th changed to the 10th, HMAS Australia and Canberra unleashed a prolonged bombardment of Karavi, while the marines’ landing craft snuck off to the west. The landings went off without a hitch, and the Japanese were legitimately surprised that the British landed without the preparatory bombardments that the Canadians relied on.

However, it made no difference. Aside from a small detachment of upstarts,[4] no forces were deployed to contest the landing. Mitsune Ushijima had intended from the start to conserve his manpower within his fortifications. That the British landed elsewhere was unexpected, but ultimately inconsequential.

The British Colonel and the General’s Colonel: Two Very Different Delegations to Chiang

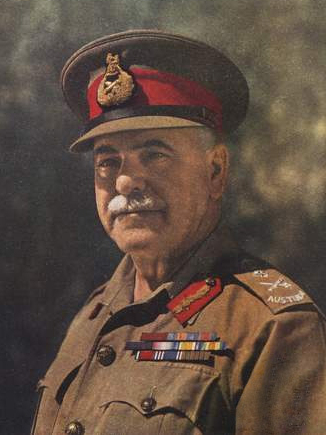

Colonel Adrian Carton de Wiart was the living embodiment of the martial traditions of the English.[5] His military experience in the Boer War, Great War, and the Soviet-Polish War were the stuff of legend. While best known for his conduct during and off-colour assessment of the Great War, it was his experience in the Polish mission that brought him to the attention of Chamberlain’s war cabinet. In Poland, he had done well toingratiate himself with the nation’s leaders, and helped maintain good relations between Poland and the United Kingdom. While his dismissive opinions of the Chinese, and east asians in general, were known, a certain degree of chauvinism had always been a part of British Imperial pomp and grandeur. He was the ideal mixture of diplomatic credentials and soldierly ruggedness for a military envoy to Chaing.

De Wiart traveled up the Burma Road by foot, donkey and truck. On the other side of the Massif, another envoy was traveling to China in comparable luxury.

Colonel Robert Samuel McLaughlin was no soldier. His rank was purely honorary and was the product of years of patronage to his county’s militia regiment. However, he was not uninvolved in military affairs. As the head of General Motors of Canada, he had a major role in the provisioning of military vehicles to Canada and its allies. He had invested significantly into the development and production of the Canadian Military Pattern Truck, and the relatively small scale of combat thus far, and reduced need for trucks on the Islands of the Pacific, meant that the supply of these vehicles significantly exceeded the British Empire’s demand for them. This would be a disheartening prospect for the company, had Canada and the wider British Empire been the only potential market.

China was a market where GM had previously enjoyed substantial success, especially during the Great Depression. Mr. McLaughlin was willing to bet that even a war-ravaged China could once more help GM overcome its spot of difficulty. So he set off on an American flagged ship from which he, his interpreters, and his load of gifts and demonstration vehicles had a simple train ride into China.

The two delegations arrived in Kunming close enough that they would proceed on to Chongqing as a single convoy. de Wiart was rather disappointed to find out that Mr. McLaughlin was neither a real colonel nor a real aristocrat. That said, he did appreciate the nouveau riche’s ability to grease palms along the way.

As it so happens, in those days a Buick was worth its weight in gold to the Chinese. It was the most prestigious and trusted brand of automobile. This desirability manifested itself in market share, 1 out of every 6 cars in China was a Buick. Mr. McLaughlin’s hall of a half dozen high end Buicks were essentially an all access pass to every nook of Chongqing’s wartime government, and where a full car would be overkill, the badge[6] could suffice.

This, while useful, unveiled a major problem for Colonel de Wiart. The amount of graft in China was unimaginable to those who were not already familiar with it. Who could be trusted to fulfill a given mission when ranks were a matter of patronage and information flowed rather than merely leaked? What equipment transferred to China would reach the frontline rather than a black market vendor? These matters were troubling to say the least.

Chaing himself, while certainly happy to accept the 1939 Buick Touring Sedan that Mr. McLaughlin had brought, was a much trickier person to deal with, as he had a clear nationalist agenda of his own. De Wiart was quite put off by the Generalissimo’s simultaneous suggestions that Britain should allow China to reclaim and keep Hong Kong, and that Britain should provide China with the material aid to do so. That Britain was only at war with Japan because the Japanese had taken Hong Kong from them was not quite appreciated.

What was appreciated was that any future loan to the Chinese would likely be spent on CMP trucks, as the three ton 4x4s thoroughly impressed during their assessment. Money that would be spent within the empire was easier to justify giving out, and Mr. McLaughlin was able to leave a happy man. Departing China in early November, he had intended to make a world traveling trip of it, taking time to visit GM’s overseas subsidiaries, Holden, Opel, and Vauxhal. Though, given the events then unfolding, the second of those had to be dropped from the itinerary.

---

[1] which was of course a conscript force.

[2] sans the Sarawak Range Companies it’d had on Borneo

[3] No relation to the more famous Mitsuru Ushijima.

[4] The deaths of these young glory-seekers during the bombardment eliminated internal criticism of the Lieutenant General’s defensive posture.

[5] despite not being English…

[6] of which Mr. McLaughlin had many. There are a number of amusing pictures of badge-swapped Fords around Chongqing.

AN:

Wow, sorry that took so long, honestly did not expect that. In any case, I wish I had gotten this done over reading break as I’d intended, as that would at least have meant that my return post for the summer would have been the Germany post, which would be much more exciting. Now that’ll have to be the next post…

With neither the Canadians nor the Marines following through on the proposed landing in New Guinea envisioned as the culmination of Operation Ball Peen, the Australians were left to go it alone. This is not to say that the Australians had been completely left hanging. The withdrawal of the IJA’s 16th Division had made advancing easy, the RN and RAF finally closing the Japanese supply lines was appreciated, even if perceived to be overdue.

That still left the prickly problem of the 21st Division and the difficulties supplying a campaign to retake the Territory of New Guinea by way of the Territory of Papua. Worse still, the Australian public did not appreciate the extent to which the campaign relied on the Australian Militia.[1] Some sort of additional aid was needed, if only to relieve militia units of their third echelon duties so more boys and men could return to their mothers and wives. So far, the only British deployment had been the 1st Infantry division, and while welcome, more was still needed to release a desirable number of Militia from their support duties on the island.

Thus came the other Southern Divisions to the rescue. The 2nd New Zealand Division, now at nearly full strength,[2] arrived in high spirits following the conclusion of the Borneo Campaign. The 1st South African Infantry Brigade also arrived in late September. At the same time a company of the Rhodesian Regiment arrived and, to the Australians’ confusion, promptly embedded itself in the New Zealanders’ command structure rather than the South Africans’.

This assorted influx would allow for the militia presence to be reduced to a more politically palatable level. If the Imperial and Commonwealth units had come expecting a glorious campaign, they were to be disappointed. General Officer Commanding Thomas Blamey saw to it that Australia’s 6th and 7th Divisions formed the frontline forces, while the Brits, Kiwis, Boers, and Rhodies, at best, performed rear area security.

Ostensibly this was to ensure that Australians secured their own territory, as they were responsible for it. This answer was not necessarily accepted by all. As one South African put it, “We were white coolies tending to the Ozzies’ bruised egos after the Navy okes prioritized Singapore over them.”

Further, there was some contention over exactly how much autonomy Blamey’s Australian GHQ should have from Gort’s Imperial General Staff. For the time being, the continued Australian advance kept official criticism and skepticism to a minimal.

Picking Up Where The Canadians Left Off: The Marines Push to Rabaul

By the 9th of September the last Canadian had departed New Britain. The Royal Marines division that replaced them had a smaller authorized strength, but with how depleted the Canadians had become, the Royal Marines were actually the larger force. Further, with Australian Citizens Forces taking over rear area duties, the Royal Marines’ frontline strength was greater than what the Canadians had first landed on New Britain with. They were in high spirits as they made rapid progress towards Rabaul.

The Imperial Japanese Army on the other hand were feeling the pinch of having their supply line severed by British air power. They had hoped to wipe the Canadians from the island and then sit in place. However, the Canadians’ Hail Mary effort and their replacement by fresh British regulars scuppered that. The choice now was between a Hail Mary effort of their own, or to bunker down and wait for the IJN to open the path for reinforcements. As an IJA man, Lieutenant General Mitsune Ushijima[3] was loath to count on the IJN for anything. But, given the logistical situation and the prior difficulties encountered when trying to assault the Canadian toe holds, the prospects for a successful offensive seemed incredibly slim. Further, as an army engineer by trade, he was one of the few IJA generals who favored earthworks over the bayonet.

In anticipation of the Canadians landing closer to Rabaul than they ended up doing, the Lt. General had a number of defensive works made around the Rabaul Caldera. These efforts were resumed and redoubled after the Canadian break out. Not only was the town surrounded by a network of trenches, but improvements were made to the caves on Mt. Vulcan, Rabalanakaia, and Tavurvur, creating an impromptu bunker network that would be immensely difficult to conquer.

Large calibre shell fire has revealed concrete and and rebar improvements to a natural cave on the Rabaul Caldera.

These construction projects were enabled by the slow pace of the British, which was less an advance and more a total relocation of the base camps established by the Canadians. Driven by his characteristic excess caution, McNaughton had landed pretty much in the middle of nowhere. As a result, the camps at Uvol and Mataburu, and all the picket sites between them, were of no use for sustaining an attack on Rabaul, the actual objective of the campaign.

The new site they selected was to be the coastal hamlet of Vunavilila, one a peninsula about a dozen kilometers west of Rabaul. Naturally, this was an ambitious target. This was a location easily reached by the enemy, meaning that a landing here would fail if the enemy opposed it. The only way to successfully land would be to do so unopposed, and with the Japanese so nearby that seemed rather unlikely.

Unless they could be misdirected.

Vunavilila was a dangerously opportunistic site for a landing, but there was an equally opportunistic target on the opposite side of the Rabaul Caldera. Karavi was a similarly sized coastal settlement about a dozen kilometers southeast of Rabaul, was practically in spitting distance of the Duke of York Islands, which would serve as the jumping off point for the Marines’ landing. If they could telegraph an attack on Karavi, they could potentially land at Vunavilila unopposed and establish a foothold before the Japanese could redeploy against the real landing site.

Throughout September, goods and personnel were moved to Duke of York Island, with no efforts made to disguise the troop movements. On the contrary, conscious efforts were made to accentuate their concentration on the southern shore. Things moved fast as the Royal Marines Division were both primarily light infantry and a binary division, meaning they had little in the way of “tail” to drag around. Within less than a month, “Operation Canadian Thanksgiving” was ready to go. As the clock struck midnight and the 9th changed to the 10th, HMAS Australia and Canberra unleashed a prolonged bombardment of Karavi, while the marines’ landing craft snuck off to the west. The landings went off without a hitch, and the Japanese were legitimately surprised that the British landed without the preparatory bombardments that the Canadians relied on.

However, it made no difference. Aside from a small detachment of upstarts,[4] no forces were deployed to contest the landing. Mitsune Ushijima had intended from the start to conserve his manpower within his fortifications. That the British landed elsewhere was unexpected, but ultimately inconsequential.

The British Colonel and the General’s Colonel: Two Very Different Delegations to Chiang

Colonel Adrian Carton de Wiart was the living embodiment of the martial traditions of the English.[5] His military experience in the Boer War, Great War, and the Soviet-Polish War were the stuff of legend. While best known for his conduct during and off-colour assessment of the Great War, it was his experience in the Polish mission that brought him to the attention of Chamberlain’s war cabinet. In Poland, he had done well toingratiate himself with the nation’s leaders, and helped maintain good relations between Poland and the United Kingdom. While his dismissive opinions of the Chinese, and east asians in general, were known, a certain degree of chauvinism had always been a part of British Imperial pomp and grandeur. He was the ideal mixture of diplomatic credentials and soldierly ruggedness for a military envoy to Chaing.

De Wiart traveled up the Burma Road by foot, donkey and truck. On the other side of the Massif, another envoy was traveling to China in comparable luxury.

Colonel Robert Samuel McLaughlin was no soldier. His rank was purely honorary and was the product of years of patronage to his county’s militia regiment. However, he was not uninvolved in military affairs. As the head of General Motors of Canada, he had a major role in the provisioning of military vehicles to Canada and its allies. He had invested significantly into the development and production of the Canadian Military Pattern Truck, and the relatively small scale of combat thus far, and reduced need for trucks on the Islands of the Pacific, meant that the supply of these vehicles significantly exceeded the British Empire’s demand for them. This would be a disheartening prospect for the company, had Canada and the wider British Empire been the only potential market.

China was a market where GM had previously enjoyed substantial success, especially during the Great Depression. Mr. McLaughlin was willing to bet that even a war-ravaged China could once more help GM overcome its spot of difficulty. So he set off on an American flagged ship from which he, his interpreters, and his load of gifts and demonstration vehicles had a simple train ride into China.

The two delegations arrived in Kunming close enough that they would proceed on to Chongqing as a single convoy. de Wiart was rather disappointed to find out that Mr. McLaughlin was neither a real colonel nor a real aristocrat. That said, he did appreciate the nouveau riche’s ability to grease palms along the way.

As it so happens, in those days a Buick was worth its weight in gold to the Chinese. It was the most prestigious and trusted brand of automobile. This desirability manifested itself in market share, 1 out of every 6 cars in China was a Buick. Mr. McLaughlin’s hall of a half dozen high end Buicks were essentially an all access pass to every nook of Chongqing’s wartime government, and where a full car would be overkill, the badge[6] could suffice.

This, while useful, unveiled a major problem for Colonel de Wiart. The amount of graft in China was unimaginable to those who were not already familiar with it. Who could be trusted to fulfill a given mission when ranks were a matter of patronage and information flowed rather than merely leaked? What equipment transferred to China would reach the frontline rather than a black market vendor? These matters were troubling to say the least.

Chaing himself, while certainly happy to accept the 1939 Buick Touring Sedan that Mr. McLaughlin had brought, was a much trickier person to deal with, as he had a clear nationalist agenda of his own. De Wiart was quite put off by the Generalissimo’s simultaneous suggestions that Britain should allow China to reclaim and keep Hong Kong, and that Britain should provide China with the material aid to do so. That Britain was only at war with Japan because the Japanese had taken Hong Kong from them was not quite appreciated.

What was appreciated was that any future loan to the Chinese would likely be spent on CMP trucks, as the three ton 4x4s thoroughly impressed during their assessment. Money that would be spent within the empire was easier to justify giving out, and Mr. McLaughlin was able to leave a happy man. Departing China in early November, he had intended to make a world traveling trip of it, taking time to visit GM’s overseas subsidiaries, Holden, Opel, and Vauxhal. Though, given the events then unfolding, the second of those had to be dropped from the itinerary.

---

[1] which was of course a conscript force.

[2] sans the Sarawak Range Companies it’d had on Borneo

[3] No relation to the more famous Mitsuru Ushijima.

[4] The deaths of these young glory-seekers during the bombardment eliminated internal criticism of the Lieutenant General’s defensive posture.

[5] despite not being English…

[6] of which Mr. McLaughlin had many. There are a number of amusing pictures of badge-swapped Fords around Chongqing.

AN:

Wow, sorry that took so long, honestly did not expect that. In any case, I wish I had gotten this done over reading break as I’d intended, as that would at least have meant that my return post for the summer would have been the Germany post, which would be much more exciting. Now that’ll have to be the next post…

Last edited:

don't forget that without war in Europe the British Empire can concentrate all its forces in the PacificIt strikes me as kind of odd that it seems to be consensus here that an Anglo-Victory without US-Involment in such a war would be guaranteed, considering the piss poor performance of the UK in the first months of OTL pacific war.

True, but would that be enough to make up for the lacking US-Involement?don't forget that without war in Europe the British Empire can concentrate all its forces in the Pacific

I am not so sure.

It's hard to say but without the war in Europe, England still has that superpower image so Japan will have a hard timeTrue, but would that be enough to make up for the lacking US-Involement?

I am not so sure.

de Wiart is a tough son of a bitch he doesn’t stop for anything.

Ye, he'll be fun to write about in future updates.Still will be interesting seeing the Chinese dealing with Carton de Wiart the toughest man in the British Empire who really isn’t one to take any crap heck I remember OTL he insulted Mao to his face when he was sent out east.

Good to see this back!

Thanks!View attachment 748716

me when I wake up to see this TL is back

It strikes me as kind of odd that it seems to be consensus here that an Anglo-Victory without US-Involment in such a war would be guaranteed, considering the piss poor performance of the UK in the first months of OTL pacific war.

don't forget that without war in Europe the British Empire can concentrate all its forces in the Pacific

True, but would that be enough to make up for the lacking US-Involement?

I am not so sure.

Things to consider:It's hard to say but without the war in Europe, England still has that superpower image so Japan will have a hard time

1) as Amon34 says Japan is getting the UK's full attention, so much greater resources can be brought to bear.

2) iOTL 1941 the Far Eastern Commands were staffed with 4th stringers (think soon to be pensioners and green officers still learning the ropes), the best of its personnel had been stripped out for service in the active campaigns.

3) (probably the most important) iotl Japan's strike south had near total surprise as well as about a year of planning and stockpiling in preparation of it. ITTL Japan stumbled into the war un-deliberately (well, un-deliberately on Tokyo's part) and struck south with minimal prep in an effort to seize ground before the UK could flood the region with reinforcements.

4) Without the occupation of FIC and Thailand as a spring board directly invading Malaya right away isn't an option.

Well, an image alone will not do much.It's hard to say but without the war in Europe, England still has that superpower image so Japan will have a hard time

I think it would be pretty hard, if not impossible, for the UK to ever regain any ground they once lost to the Japanese, because they, even with their empire, can't match the industrial power of the US and would be fighting with a greater loss of strength gradient.

So in the ideal case for the UK they would win defensive Victory after defensive Victory against the Japanese (very unlikely though) and could eventually reach a white peace that allows them to keep their Status quo in the pacific.

But any talk about the UK taking territories from the Japanese, let alone setting foot on their homeland pretty much seem like ASB Anglowank to me.

Problem is Imperial Japan has a lot organisational and logistical issues that don’t really get highlighted until they get dragged into a major conflict, like they don’t really have the ability to sustain a prolonged war against a major power and at a strategic level there is no clear goal or war plan. To say nothing about the shambolic state of logistics and RnD as well as ship design and construction. Like for an exmaple from its inception the zero was an amazing fighter but it rapidly fell behind the American fighters as they got better to say nothing of the spits.

But any talk about the UK taking territories from the Japanese, let alone setting foot on their homeland pretty much seem like ASB Anglowank to me.

I could see Britain take over some of Japan’s pacific islands. But anything more than that, like an invasion of Taiwan or driving Japan out of China, would probably require Britain switching to a total war economy. An invasion of the home islands on the other hand is pretty much out of the question.

Anyway, great to see this continue.

I think Britain will ultimately try to starve Japan into submission. Their ASW capabilites were garbage afterall.I could see Britain take over some of Japan’s pacific islands. But anything more than that, like an invasion of Taiwan or driving Japan out of China, would probably require Britain switching to a total war economy. An invasion of the home islands on the other hand is pretty much out of the question.

Anyway, great to see this continue.

Share: