You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Italico Valore - A more successful 1848 revolution in Italy - a TL

Oh crap. I hope that, should the Ottomans lose (I want them to win), Alexander II scores a genuine victory rather than the pitiful one he got OTL.

What's the betting Albania eventually ends up with a Savoyard on the throne, and gets honorary membership of the Confederation/whatever it ends up being?

Deleted member 147289

Albania in the Confederation would mean that Austria is bottled up in the Adriatic which is something Austria can't allow and would definitely intervene against Italy in case of such an event.What's the betting Albania eventually ends up with a Savoyard on the throne, and gets honorary membership of the Confederation/whatever it ends up being?

Italy is not far from the war but the Balkans are still not a priority to the government. At the same time Austria still has good relations with the Russians.

I assume that will end very soon. And yeah, Austria would never accept an Italian Albania without a war.At the same time Austria still has good relations with the Russians.

Definitely. Although I guess the first competition would be economic. But Italian and Austrian interests in the Balkans are destined to collide, be in Albania, Croatia, Slovenia. And we cannot forget that there is still part of Italy under Austrian rule...I assume that will end very soon. And yeah, Austria would never accept an Italian Albania without a war.

In 1871 Carol was not "king of Romania", but rather Domnitor (Prince) of Wallachia and Moldova (he became king of Romania only in 1881).

The Tanzimat reforms were never applied generally to all the territories of the OE, but mostly concentrated in Western Anatolia and in those parts of the Balkans were there was a Turkish majority (or at least a strong presence), and quite often encountered a strong opposition by the ruling Muslim aristocracy and landholders (this happened for example in Bosnia starting in the early 1870s).

The variant of pan-Slavic doctrine developed in Russia in the late 1860s called for all the lands east of a line from Stettin to Trieste to be a Slavic confederacy under the protection of the Czar: the only exception was Poland, which was considered a traitor to pan-Slavism having been contaminated by western ideals.

The Tanzimat reforms were never applied generally to all the territories of the OE, but mostly concentrated in Western Anatolia and in those parts of the Balkans were there was a Turkish majority (or at least a strong presence), and quite often encountered a strong opposition by the ruling Muslim aristocracy and landholders (this happened for example in Bosnia starting in the early 1870s).

The variant of pan-Slavic doctrine developed in Russia in the late 1860s called for all the lands east of a line from Stettin to Trieste to be a Slavic confederacy under the protection of the Czar: the only exception was Poland, which was considered a traitor to pan-Slavism having been contaminated by western ideals.

Deleted member 147289

Right about Carol, Romania didn't exist back then, my mistake.In 1871 Carol was not "king of Romania", but rather Domnitor (Prince) of Wallachia and Moldova (he became king of Romania only in 1881).

The Tanzimat reforms were never applied generally to all the territories of the OE, but mostly concentrated in Western Anatolia and in those parts of the Balkans were there was a Turkish majority (or at least a strong presence), and quite often encountered a strong opposition by the ruling Muslim aristocracy and landholders (this happened for example in Bosnia starting in the early 1870s).

The variant of pan-Slavic doctrine developed in Russia in the late 1860s called for all the lands east of a line from Stettin to Trieste to be a Slavic confederacy under the protection of the Czar: the only exception was Poland, which was considered a traitor to pan-Slavism having been contaminated by western ideals.

The Tanzimat reforms had more time to develop due to the long peace and no Crimean War and are thus more effective than OTL but this doesn't mean that the OE isn't the Sick Man anymore. But reforms in Anatolia and Turkish majority areas are more ingrained in the local structure.

28. THE BALKAN WAR

Deleted member 147289

28. THE BALKAN WAR

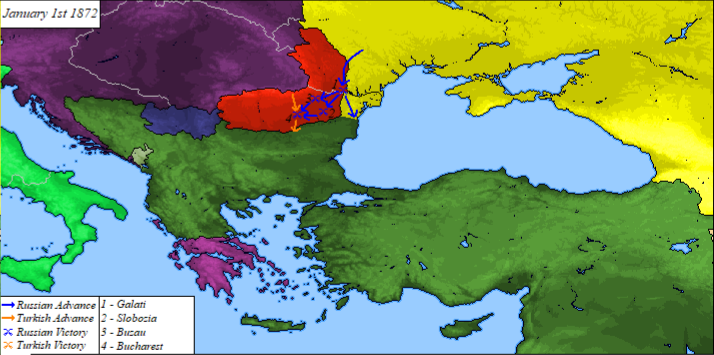

The Balkans at the beginning of the war

Before starting to detail the events of the war it is necessary to have some background on the Balkan situation and its peoples in order to better understand future events. There were three independent Balkan nations, Greece, Serbia and Montenegro, which had freed themselves from Turkish control through rebellions or, in the case of Greece, foreign interventions. These nations stared hungrily at the territories inhabited by their compatriots still controlled by the Ottomans and for years they had been waiting for an opportunity to reclaim these lands, sending weapons and equipment to the numerous groups of insurgents who operated clandestinely. The Turks had spread sufficiently in the Balkans, although never sufficiently to form a majority or a large minority within the regions they settled in, however polarizing nationalities against them who also saw them in the process of colonizing their own. lands and pouring fuel on the Balkan fire.

A 50,000-strong Ottoman army under Ahmed Muhtar's command crossed the bridges over the Danube, disarming or dispersing the few hundred Romanian guards guarding the bridges, marching straight to Bucharest in hopes of besieging the city and forcing the Domnitor to retract the its position and re-establish dependence with the Empire. The main body crossed the Danube at Ruse but the inadequacy of the infrastructure to handle such a massive flow of soldiers meant that Muhtar's army arrived on the opposite bank of the Danube on May 5th, ready to move to Bucharest where Carol I had had time to prepare some defenses, fortifying the city and concentrating the 40,000 men of the united army of Wallachia and Moldavia there.

On 8 May the siege of the city began: the Romanians resisted tenaciously for three weeks in the hope of being joined by the Russian armies that rumors spread to keep morale high wanted to be in Moldova and headed for the capital. In reality Russia was still gathering its forces from the vast empire and the bad condition of local infrastructure made this operation long and tedious, making the time gained by the Romanians essential to allow the organization of a Russian army.

When Bucharest fell, Carol fled first to Ploiesti and then to Iasu, accompanied by the 15,000 survivors of the principality's army, where she arrived in mid-June. Here he met with the First Russian Army commanded by Pyotr Vannovsky, with 150,000 men ready to drive the Turks back across the Danube. Receiving no proposal to surrender, the Ottomans sent reinforcements to Ahmed Muhtar, increasing his strength to 80,000 men who were dispersing along Wallachia to keep the area under control and suppress the partisans who were popping up like mushrooms.

The Wallachian campaign began on June 24, 1871 with the Battle of Galati where 25,000 Russians defeated 10,000 Ottomans garrisoning the city. Having conquered the port on the Danube, the Russian army, with 25,000 Wallachian and Moldovan volunteers, split into two armies, the first directed towards Slobozia and the second towards Focsani and Buzau. Muhtar did not waste his forces in trying to counter the enemy, letting them advance by exchanging time for land, during which time his forces fortified Budapest, Slobozia and Ploiesti, where they would meet the enemy.

The first major battle of the war was that of Slobozia where about 90,000 Russians and Romanians clashed against 40,000 Ottomans. Despite the numerical inferiority, the Ottoman forces managed to resist for two weeks, well entrenched and supported by most of the cannons present in Wallachia, attracting the Russian troops in prepared death zones and mowing them down, but in the end the Russian numerical superiority, as well as to the skill of their general, he won the day by driving the Ottomans out of the city. Vannovsky decided to ignore Ploiesti, ordering the army from Buzau to aim directly at Bucharest, where about 140,000 soldiers descended in early September. At the sight of the Russians the city rose up and what should have been a heroic resistance turned into a ferocious urban battle with the Ottomans squeezed between the population and the enemy army outside the city, suffering heavy losses but managing to not be completely annihilated.

With the fall of Bucharest on September 10th, Muhtar managed to bring 30,000 men back to the other side of the Danube, taking refuge in Bulgaria where another 50,000 men mobilized from central Anatolia were waiting for him. The Ottoman army was much better organized than in the past and the introduction of a primordial form of conscription allowed it to fill the ranks more easily than before. The new army of 80,000 Turks entrenched themselves along the Danube, foiling four Russian attempts to cross the river, all of which ended in un bloody failure for attackers who were unable to cross the river under enemy fire. At the end of November both powers entrenched themselves along the Danube looking from opposite banks and the war fell into a stalemate: the Russians had completed their goal, which is to preserve the independence of the United Principalities, but had not yet sent requests to the Ottomans. . The St. Petersburg court was determined to continue the war and unleash an insurrection in the Balkans, to realize the Pan-Slavic ambitions of the policy makers.

During the first year the war was seen as a localized event in the Balkans that would have no repercussions on the continent in general: it was after all a war between Russia and the Ottoman Empire, but the European Great Powers had their own agenda regarding the crisis. Oriental now degenerated into a real war. For Great Britain it was essential to prevent the Russians from entering the Mediterranean, as well as the conquest of the Dardanelles. France saw the Ottoman Empire as an effective balance for the Russians and had an interest in preserving the Turkish territorial integrity and Austria was on excellent terms with the Russians but had not yet intervened in the conflict despite numerous requests from St. Petersburg, Maximilian preferred to wait for an auspicious moment.

The Balkans at the beginning of the war

A 50,000-strong Ottoman army under Ahmed Muhtar's command crossed the bridges over the Danube, disarming or dispersing the few hundred Romanian guards guarding the bridges, marching straight to Bucharest in hopes of besieging the city and forcing the Domnitor to retract the its position and re-establish dependence with the Empire. The main body crossed the Danube at Ruse but the inadequacy of the infrastructure to handle such a massive flow of soldiers meant that Muhtar's army arrived on the opposite bank of the Danube on May 5th, ready to move to Bucharest where Carol I had had time to prepare some defenses, fortifying the city and concentrating the 40,000 men of the united army of Wallachia and Moldavia there.

On 8 May the siege of the city began: the Romanians resisted tenaciously for three weeks in the hope of being joined by the Russian armies that rumors spread to keep morale high wanted to be in Moldova and headed for the capital. In reality Russia was still gathering its forces from the vast empire and the bad condition of local infrastructure made this operation long and tedious, making the time gained by the Romanians essential to allow the organization of a Russian army.

When Bucharest fell, Carol fled first to Ploiesti and then to Iasu, accompanied by the 15,000 survivors of the principality's army, where she arrived in mid-June. Here he met with the First Russian Army commanded by Pyotr Vannovsky, with 150,000 men ready to drive the Turks back across the Danube. Receiving no proposal to surrender, the Ottomans sent reinforcements to Ahmed Muhtar, increasing his strength to 80,000 men who were dispersing along Wallachia to keep the area under control and suppress the partisans who were popping up like mushrooms.

The Wallachian campaign began on June 24, 1871 with the Battle of Galati where 25,000 Russians defeated 10,000 Ottomans garrisoning the city. Having conquered the port on the Danube, the Russian army, with 25,000 Wallachian and Moldovan volunteers, split into two armies, the first directed towards Slobozia and the second towards Focsani and Buzau. Muhtar did not waste his forces in trying to counter the enemy, letting them advance by exchanging time for land, during which time his forces fortified Budapest, Slobozia and Ploiesti, where they would meet the enemy.

The first major battle of the war was that of Slobozia where about 90,000 Russians and Romanians clashed against 40,000 Ottomans. Despite the numerical inferiority, the Ottoman forces managed to resist for two weeks, well entrenched and supported by most of the cannons present in Wallachia, attracting the Russian troops in prepared death zones and mowing them down, but in the end the Russian numerical superiority, as well as to the skill of their general, he won the day by driving the Ottomans out of the city. Vannovsky decided to ignore Ploiesti, ordering the army from Buzau to aim directly at Bucharest, where about 140,000 soldiers descended in early September. At the sight of the Russians the city rose up and what should have been a heroic resistance turned into a ferocious urban battle with the Ottomans squeezed between the population and the enemy army outside the city, suffering heavy losses but managing to not be completely annihilated.

With the fall of Bucharest on September 10th, Muhtar managed to bring 30,000 men back to the other side of the Danube, taking refuge in Bulgaria where another 50,000 men mobilized from central Anatolia were waiting for him. The Ottoman army was much better organized than in the past and the introduction of a primordial form of conscription allowed it to fill the ranks more easily than before. The new army of 80,000 Turks entrenched themselves along the Danube, foiling four Russian attempts to cross the river, all of which ended in un bloody failure for attackers who were unable to cross the river under enemy fire. At the end of November both powers entrenched themselves along the Danube looking from opposite banks and the war fell into a stalemate: the Russians had completed their goal, which is to preserve the independence of the United Principalities, but had not yet sent requests to the Ottomans. . The St. Petersburg court was determined to continue the war and unleash an insurrection in the Balkans, to realize the Pan-Slavic ambitions of the policy makers.

During the first year the war was seen as a localized event in the Balkans that would have no repercussions on the continent in general: it was after all a war between Russia and the Ottoman Empire, but the European Great Powers had their own agenda regarding the crisis. Oriental now degenerated into a real war. For Great Britain it was essential to prevent the Russians from entering the Mediterranean, as well as the conquest of the Dardanelles. France saw the Ottoman Empire as an effective balance for the Russians and had an interest in preserving the Turkish territorial integrity and Austria was on excellent terms with the Russians but had not yet intervened in the conflict despite numerous requests from St. Petersburg, Maximilian preferred to wait for an auspicious moment.

Last edited by a moderator:

Seems like the Russians have the upper hand right now, but only because of their huge numerical advantage. My guess is that they'll score a very expensive and pyrrhic victory, just like OTL. Hopefully we can have a compromise peace where the Ottomans can keep Bulgaria and Romania's independence is recognized.

Deleted member 147289

We're in for a lot of fun in the Balkans and for fun I mean war which is a sport there. The Russians will try to retake Wallachia, and the Turks will oppose them. Russia vs the Ottomans is a curbstomp, but the main issue are the other GPs that could intervene if Russia goes too far or the OE starts to crumble; mainly Britain.

Sure doesn't look like it... 30.000 Turks holding an army three times their size at bay for two weeks? And the OTL 1877-78 war wasn't so easy for AII either: Plevna held out against the Russians for five months, and AFAIK the Ottomans ITTL didn't commit any major atrocities that left them internationally isolated.Russia vs the Ottomans is a curbstomp

Last edited:

29. THE LONG YEAR

Deleted member 147289

29. THE LONG YEAR

During the remainder of 1871 the Russian troops tried twice more to cross the Danube, the first attempt failed, the second was a success with the creation of a bridgehead in Douruja, with the Russian advance reaching Constance before being stopped by the Ottoman reinforcements which quickly flowed into the region to plug the holes. At the end of the year there were, along the Danube, about 300,000 Russians and 180,000 Ottomans, entrenched on both sides. The winter brought the fighting to an end but in St. Petersburg the more hawkish voices were pressing on the Tsar for an escalation of the war. Alexander II was sympathetic to the most warlike voices, wishing to strike at his ancient rival and extend the influence of the Empire to the shores of the Mediterranean, which has always been Russia's strategic objective. The Tsar ordered his high command to prepare plans for a new offensive against the Ottomans and ordered the ambassador to Austria to lobby for Austrian intervention in the conflict.

The situation at the beginning of 1872: with Moldova recaptured, the Russians were stalled on the Danube until they managed to cross into northern Dobruja

Great Britain looked at the conflict in the Balkans with anxiety: the British and Russian Empire had been engaged for two decades in what was called the Great Game, a series of diplomatic, military and colonial moves carried out by the two empires with conflicting objectives : for the Russians it was to reach India and the Mediterranean, for the British it was to maintain their dominion over these areas and repel Russian incursions. The Ottoman Empire was only a pawn in this global chessboard but it was a crucial pawn: its fall would have led to the opening of the Bosphorus to Russian ships and their entry into the Mediterranean. It was therefore crucial that England support the "sick man of Europe" with loans, weapons and instructors, as the Empire was at risk. But if the situation became critical, a limited military intervention, perhaps together with France or Italy, was kept on the cards at Westminster.

In the spring, the 120,000-strong Russian Second Army led by Grigol Dadiani attacked along the Caucasus Mountains from Georgia to Armenia, surprising Ottoman troops who did not expect a Russian attack. The garrisons had been reduced to send to reinforce the Balkans, trusting that the war would remain localized along the Danube and that the Russians would not launch an offensive from the Caucasus given the difficulty of the terrain. Despite this, numerous positions resisted the Russian attack for days but this did not prevent the attackers from breaching numerous points from which they could encircle the Turkish defenses, forcing the defenders to retreat.

The Russian navy had its moment of glory off the coast of Trebizond when a squadron of 10 ships among the most modern of the Black Sea fleet, ambushed a convoy of Ottoman ships consisting of 12 merchant ships and 6 warships, two steam frigates built by England and four sailboats. In half an hour the Ottoman fleet had been sunk by the Russian ships that had approached covered in fog and opened fire. The Tsar was pleased with the victory, which raised the morale of the army, stalled along the Danube and stopped in Anatolia. By early June the Russians had reached Kars in the Eastern Anatolian plateau and advanced to the port of Rize along the coast, before being stopped by the terrain which prevented the Russians from using their mass tactics, allowing the Ottoman defenders. to concentrate forces in a few strategic points to stop the enemy advance, causing the offensive to degenerate into a high-altitude position war in which rudimentary trenches were dug.

Frustrated by the lack of success, the Russian High Command decided on another offensive before the winter, to take place in Dobruja. On July 2, 1872, 150,000 Russians charged into the Ottoman trenches between Mangralia and Silistra, covered by artillery and ships where possible. The Turks who had one man for every three Russians but had had almost a year to entrench themselves, managed to inflict heavy losses on the attackers, making them pay dearly for every meter of land, but the Russian numbers won the battle in the end, managing to break through and advancing in Bulgaria, headed for Varna. The Ottoman command moved everything they had to Bulgaria but as soon as the Turkish troops left the Danube unguarded the Russians launched another assault which was successful without too many casualties. The Ottomans panicked and began a disorganized retreat to the Balkan mountains where, thanks to the coming winter, they stopped the Russian advance 100 km from Sofia.

Russian Cavalry smashing Ottoman defences on the Bulgarian plain

With the Russian advance the Balkan peoples also rose, causing many distractions to the Ottomans: the Bulgarians disturbed the lines of communication between the front line and Constantinople, the Serbs started a guerrilla war in the areas of their majority, hitting the Ottoman garrisons and the administrative functions inciting the population to revolt. This work was particularly successful with the Serbs in Bosnia who rose up in autumn, driving out the Ottoman garrisons and hunting down collaborators. Greece was hesitant: the Russian advance was too far from its borders which were always guarded by numerous Ottoman troops and without Serbia and Montenegro they did not want to risk entering into conflict alone against the Empire.

The Sublime Porte begged England to send further aid and reinforcements, unable to contain the Russian invasion on two fronts and to preserve the integrity of the Empire in its outlying areas. Seeing the writing on the wall, Prime Minister Disraeli began sending troops and ships to Turkey and the Black Sea but also testing the terrain between the European embassies to build an anti-Russian expeditionary force, especially between France and Italy.

In late 1872 the Russian army broke through the lines on the Danube and advanced in southern Dobruja and Bulgaria, towards the Balkan mountains, while the Turks had to retreat to avoid being encircled

During the remainder of 1871 the Russian troops tried twice more to cross the Danube, the first attempt failed, the second was a success with the creation of a bridgehead in Douruja, with the Russian advance reaching Constance before being stopped by the Ottoman reinforcements which quickly flowed into the region to plug the holes. At the end of the year there were, along the Danube, about 300,000 Russians and 180,000 Ottomans, entrenched on both sides. The winter brought the fighting to an end but in St. Petersburg the more hawkish voices were pressing on the Tsar for an escalation of the war. Alexander II was sympathetic to the most warlike voices, wishing to strike at his ancient rival and extend the influence of the Empire to the shores of the Mediterranean, which has always been Russia's strategic objective. The Tsar ordered his high command to prepare plans for a new offensive against the Ottomans and ordered the ambassador to Austria to lobby for Austrian intervention in the conflict.

The situation at the beginning of 1872: with Moldova recaptured, the Russians were stalled on the Danube until they managed to cross into northern Dobruja

Great Britain looked at the conflict in the Balkans with anxiety: the British and Russian Empire had been engaged for two decades in what was called the Great Game, a series of diplomatic, military and colonial moves carried out by the two empires with conflicting objectives : for the Russians it was to reach India and the Mediterranean, for the British it was to maintain their dominion over these areas and repel Russian incursions. The Ottoman Empire was only a pawn in this global chessboard but it was a crucial pawn: its fall would have led to the opening of the Bosphorus to Russian ships and their entry into the Mediterranean. It was therefore crucial that England support the "sick man of Europe" with loans, weapons and instructors, as the Empire was at risk. But if the situation became critical, a limited military intervention, perhaps together with France or Italy, was kept on the cards at Westminster.

In the spring, the 120,000-strong Russian Second Army led by Grigol Dadiani attacked along the Caucasus Mountains from Georgia to Armenia, surprising Ottoman troops who did not expect a Russian attack. The garrisons had been reduced to send to reinforce the Balkans, trusting that the war would remain localized along the Danube and that the Russians would not launch an offensive from the Caucasus given the difficulty of the terrain. Despite this, numerous positions resisted the Russian attack for days but this did not prevent the attackers from breaching numerous points from which they could encircle the Turkish defenses, forcing the defenders to retreat.

The Russian navy had its moment of glory off the coast of Trebizond when a squadron of 10 ships among the most modern of the Black Sea fleet, ambushed a convoy of Ottoman ships consisting of 12 merchant ships and 6 warships, two steam frigates built by England and four sailboats. In half an hour the Ottoman fleet had been sunk by the Russian ships that had approached covered in fog and opened fire. The Tsar was pleased with the victory, which raised the morale of the army, stalled along the Danube and stopped in Anatolia. By early June the Russians had reached Kars in the Eastern Anatolian plateau and advanced to the port of Rize along the coast, before being stopped by the terrain which prevented the Russians from using their mass tactics, allowing the Ottoman defenders. to concentrate forces in a few strategic points to stop the enemy advance, causing the offensive to degenerate into a high-altitude position war in which rudimentary trenches were dug.

Frustrated by the lack of success, the Russian High Command decided on another offensive before the winter, to take place in Dobruja. On July 2, 1872, 150,000 Russians charged into the Ottoman trenches between Mangralia and Silistra, covered by artillery and ships where possible. The Turks who had one man for every three Russians but had had almost a year to entrench themselves, managed to inflict heavy losses on the attackers, making them pay dearly for every meter of land, but the Russian numbers won the battle in the end, managing to break through and advancing in Bulgaria, headed for Varna. The Ottoman command moved everything they had to Bulgaria but as soon as the Turkish troops left the Danube unguarded the Russians launched another assault which was successful without too many casualties. The Ottomans panicked and began a disorganized retreat to the Balkan mountains where, thanks to the coming winter, they stopped the Russian advance 100 km from Sofia.

Russian Cavalry smashing Ottoman defences on the Bulgarian plain

With the Russian advance the Balkan peoples also rose, causing many distractions to the Ottomans: the Bulgarians disturbed the lines of communication between the front line and Constantinople, the Serbs started a guerrilla war in the areas of their majority, hitting the Ottoman garrisons and the administrative functions inciting the population to revolt. This work was particularly successful with the Serbs in Bosnia who rose up in autumn, driving out the Ottoman garrisons and hunting down collaborators. Greece was hesitant: the Russian advance was too far from its borders which were always guarded by numerous Ottoman troops and without Serbia and Montenegro they did not want to risk entering into conflict alone against the Empire.

The Sublime Porte begged England to send further aid and reinforcements, unable to contain the Russian invasion on two fronts and to preserve the integrity of the Empire in its outlying areas. Seeing the writing on the wall, Prime Minister Disraeli began sending troops and ships to Turkey and the Black Sea but also testing the terrain between the European embassies to build an anti-Russian expeditionary force, especially between France and Italy.

In late 1872 the Russian army broke through the lines on the Danube and advanced in southern Dobruja and Bulgaria, towards the Balkan mountains, while the Turks had to retreat to avoid being encircled

Last edited by a moderator:

Good stuff, I like where this is going. It's pretty consistent with OTL, as there was nothing specific mentioned here about avoiding changes to the Ottoman officer corps, so there's a limit to how successful the Ottomans are likely to be barring major butterfly effect. A better performance despite the losses in the high command is perfectly plausible

Added maps to last chapters, credit to @Drex. Any opinion on the war so far?

Stuff will happen. Much stuff.

30. ESCALATION

Deleted member 147289

30. ESCALATION

The Ottoman situation in early 1873 was not the best: the natural barrier of the Danube had been breached and now an exhausted and undersupplied army stood between nearly half a million Russians and central Bulgaria, already in revolt like most of the Balkans: in Bosnia the Ottoman authority had even been expelled while in Montenegro and southern Serbia the army was helping the gendarmerie in the suppression of the revolts but with little effectiveness. The terrain of Eastern Anatolia had slowed the Russians but did not stop them, sooner or later they would break through the defenses using their numbers being able to take losses that the Ottomans could not afford. After two years of war the Sublime Porte had difficulty in finding manpower to swell the ranks, the population had begun to suffer the central authority for the death of loved ones and some fringe voices in the privy council had supported ideas of decentralization and revocation of various previously implemented reforms, putting the war effort of Europe's sick man at serious risk.

Fortunately for them, they were not alone. Britain had sent an expeditionary force of 50,000 men which arrived in Bulgaria in the early spring, with more reinforcements arriving from across the empire, along with supplies and weapons the Ottomans desperately needed. British efforts to build an anti-Russian coalition had been in vain: Austria had a good relationship with Russia and was watching the Balkans with interest. Prussia was busy consolidating its control over northern Germany and France had more interest in colonial adventures in Africa than in Europe. Italy was the only one to accept England's request, made sweeter by the stipulation of various treaties that guaranteed Italians access to British ports along the route to China, but also British diplomatic support for the creation of a future colony in Asia. Thus it was that the Italian Confederation sent an expeditionary force of 40,000 men, whose peculiarity was to belong not to the armies of the individual nations but to the Confederate Army. Italian troops along with British reinforcements would be used in a daring plan to distract Russian forces and take pressure off the Ottomans, an operation planned for the summer.

Unfortunately for the Allies the Russian position improved considerably during the spring of 1873: after months of skirmishes the Tsarist army attacked Sofia in force, taking the city after four days of fighting. In this battle the recently arrived British troops faced off with the Russian veterans but the training and quality of the equipment allowed the British not to be overwhelmed like the Turks, who were starting to be demoralized. But the most radical change of the war came in May, when Austria exploited the state of lawlessness and order in Bosnia to justify a military intervention aimed at protecting the German minority and stabilizing the borders of the Empire. The result was the de facto annexation of Bosnia to Austria, an event that amazed many international observers now sure of Austria's non-interventionist foreign policy but the real reason lay in the loss of influence in Northern Germany, along with the control over local principles increasingly linked to Prussia thanks to the machinations of Bismarck, which had determined a loss of imperial prestige that was to be restored with a Balkan expansion.

Russian soldiers recieved a hero's welcome in Sofia after it's liberation

The entry of Austria into the Balkan disaster did nothing but inflame relations between great powers: the United Kingdom and Italy had not yet declared war on Austria and decided to wait for the next move by the Empire before attacking it or asking a withdrawal. In the meantime, Italy had moved most of its troops to Veneto along the border with Austria in case there was a further escalation to the war, cutting the second planned expeditionary force from 40,000 men to 20,000. Russia congratulated its ally for the intervention and hoped for its descent into the Balkans to free the oppressed populations, but Austria actually had no intention of continuing with the advance: the war was an excellent opportunity to expand its own domains and good relations with Russia would have meant a sure support for the annexation, but now the Empire also had to exercise caution with Great Britain in order not to attract it's ire and those of their Italian lackey, so Maximilian replied to the ambassador that the Austrian army was busy restoring order in Bosnia and, due to the cuts in the military budget, would not have been ready for further advances, but made vague allusions to future interventions that were enough to appease the Russians, confident in the intervention of their ally.

After the capture of Sofia, General Vannovsky and his staff decided to devise a new strategy to defeat the Ottomans: instead of dislodging the enemy and from the Balkan mountains, the Russian army would strike the flanks of the empire, inciting or favoring the local populations already in revolt who saw their protector in the Russian army. Therefore an army corps that numbered more than 150,000 men was set up between Sofia and the Danube, with the aim of advancing towards Nis and Montenegro. The Russians did not want to abandon their Bulgarian allies but Vannovsky wanted to capitalize on the greater intensity of the revolts in the western part of the empire but also in the probable intervention of Serbia and Montenegro in support of their compatriots. The offensive began in early June, weakly opposed by the Ottoman army, always outnumbered, and by the irregular militias who were worse soldiers than the Russian conscripts, and reached Nis on the 16th and began the its penetration into central Serbia while the Principality of Serbia, after an exhausting Russian lobbing, declared war on the Ottoman Empire and sent its small army beyond the borders, towards the Russian one.

The Russian offensive took the Allies by surprise who expected a war of attrition along the Balkans where they could use their equipment to block the Russians, forcing the military leaders to anticipate the Crimean landings scheduled for early August to early July, with half the men and the ships. On July 6, 20,000 British and 10,000 Italians landed near Sevastopol covered by the Royal Navy and Confederate Navy which in the previous six months had contended for domination of the Black Sea with the Russian Imperial Navy which was now on the seabed or safe in its ports. first of all Sevastopol which was the base of the Black Sea Fleet. Occupying it was of vital importance for the Allies who could not reinforce the landed army without a port.

British commander Appleyard led the Allied expeditionary force to Bakalava to secure a port from which to deliver the supplies on which the invasion depended. The city fell on July 26, but then the Russians had received reinforcements from Galicia with whom they had begun to attack the expeditionary force to drive it back into the sea, but the English and Italians resisted tenaciously, managing to besiege Sevastopol. At the beginning of September there were about 50,000 Italians and 40,000 British in the Crimea who managed to distract 150,000 Russians by opening a new front in a strategic area. The flow of Russian divisions in the Crimea eased the pressure on the Balkan front where Vannovsky had to stop the offensive in Central Serbia, but managed to rejoin the Serbian army coming from the north.

With the arrival of winter, both sides reduced their military operations, limiting themselves to skirmishes along the border. The Russians had been contained to the north of the Balkan mountains but had reached the Serbs and extended the front line to the east, super-extending the already small Ottoman manpower that had to leave large sections of the Bulgarian front to the now 120,000 British from all over the empire that were taking on more and more of the war effort. The Italians were holding Sevastopol under siege, forcing the Russians to diverge more and more men on the peninsula. Great Russia had no manpower problems, but after three years of fighting it was losing many veterans and rapidly consuming previously accumulated reserves of war material. Russia's bad logistical situation had only recently begun to improve but not fast enough to ensure a continuous flow of supplies to the million men in the field, forcing commanders to conserve resources. The Russian high command told the Tsar that supplies for next year were not enough for a major offensive but that they would have to stay on the defensive until they resolved the situation or found an opening. The initiative thus passed into the hands of the allies.

The Balkans in late 1873

The Ottoman situation in early 1873 was not the best: the natural barrier of the Danube had been breached and now an exhausted and undersupplied army stood between nearly half a million Russians and central Bulgaria, already in revolt like most of the Balkans: in Bosnia the Ottoman authority had even been expelled while in Montenegro and southern Serbia the army was helping the gendarmerie in the suppression of the revolts but with little effectiveness. The terrain of Eastern Anatolia had slowed the Russians but did not stop them, sooner or later they would break through the defenses using their numbers being able to take losses that the Ottomans could not afford. After two years of war the Sublime Porte had difficulty in finding manpower to swell the ranks, the population had begun to suffer the central authority for the death of loved ones and some fringe voices in the privy council had supported ideas of decentralization and revocation of various previously implemented reforms, putting the war effort of Europe's sick man at serious risk.

Fortunately for them, they were not alone. Britain had sent an expeditionary force of 50,000 men which arrived in Bulgaria in the early spring, with more reinforcements arriving from across the empire, along with supplies and weapons the Ottomans desperately needed. British efforts to build an anti-Russian coalition had been in vain: Austria had a good relationship with Russia and was watching the Balkans with interest. Prussia was busy consolidating its control over northern Germany and France had more interest in colonial adventures in Africa than in Europe. Italy was the only one to accept England's request, made sweeter by the stipulation of various treaties that guaranteed Italians access to British ports along the route to China, but also British diplomatic support for the creation of a future colony in Asia. Thus it was that the Italian Confederation sent an expeditionary force of 40,000 men, whose peculiarity was to belong not to the armies of the individual nations but to the Confederate Army. Italian troops along with British reinforcements would be used in a daring plan to distract Russian forces and take pressure off the Ottomans, an operation planned for the summer.

Unfortunately for the Allies the Russian position improved considerably during the spring of 1873: after months of skirmishes the Tsarist army attacked Sofia in force, taking the city after four days of fighting. In this battle the recently arrived British troops faced off with the Russian veterans but the training and quality of the equipment allowed the British not to be overwhelmed like the Turks, who were starting to be demoralized. But the most radical change of the war came in May, when Austria exploited the state of lawlessness and order in Bosnia to justify a military intervention aimed at protecting the German minority and stabilizing the borders of the Empire. The result was the de facto annexation of Bosnia to Austria, an event that amazed many international observers now sure of Austria's non-interventionist foreign policy but the real reason lay in the loss of influence in Northern Germany, along with the control over local principles increasingly linked to Prussia thanks to the machinations of Bismarck, which had determined a loss of imperial prestige that was to be restored with a Balkan expansion.

Russian soldiers recieved a hero's welcome in Sofia after it's liberation

The entry of Austria into the Balkan disaster did nothing but inflame relations between great powers: the United Kingdom and Italy had not yet declared war on Austria and decided to wait for the next move by the Empire before attacking it or asking a withdrawal. In the meantime, Italy had moved most of its troops to Veneto along the border with Austria in case there was a further escalation to the war, cutting the second planned expeditionary force from 40,000 men to 20,000. Russia congratulated its ally for the intervention and hoped for its descent into the Balkans to free the oppressed populations, but Austria actually had no intention of continuing with the advance: the war was an excellent opportunity to expand its own domains and good relations with Russia would have meant a sure support for the annexation, but now the Empire also had to exercise caution with Great Britain in order not to attract it's ire and those of their Italian lackey, so Maximilian replied to the ambassador that the Austrian army was busy restoring order in Bosnia and, due to the cuts in the military budget, would not have been ready for further advances, but made vague allusions to future interventions that were enough to appease the Russians, confident in the intervention of their ally.

After the capture of Sofia, General Vannovsky and his staff decided to devise a new strategy to defeat the Ottomans: instead of dislodging the enemy and from the Balkan mountains, the Russian army would strike the flanks of the empire, inciting or favoring the local populations already in revolt who saw their protector in the Russian army. Therefore an army corps that numbered more than 150,000 men was set up between Sofia and the Danube, with the aim of advancing towards Nis and Montenegro. The Russians did not want to abandon their Bulgarian allies but Vannovsky wanted to capitalize on the greater intensity of the revolts in the western part of the empire but also in the probable intervention of Serbia and Montenegro in support of their compatriots. The offensive began in early June, weakly opposed by the Ottoman army, always outnumbered, and by the irregular militias who were worse soldiers than the Russian conscripts, and reached Nis on the 16th and began the its penetration into central Serbia while the Principality of Serbia, after an exhausting Russian lobbing, declared war on the Ottoman Empire and sent its small army beyond the borders, towards the Russian one.

The Russian offensive took the Allies by surprise who expected a war of attrition along the Balkans where they could use their equipment to block the Russians, forcing the military leaders to anticipate the Crimean landings scheduled for early August to early July, with half the men and the ships. On July 6, 20,000 British and 10,000 Italians landed near Sevastopol covered by the Royal Navy and Confederate Navy which in the previous six months had contended for domination of the Black Sea with the Russian Imperial Navy which was now on the seabed or safe in its ports. first of all Sevastopol which was the base of the Black Sea Fleet. Occupying it was of vital importance for the Allies who could not reinforce the landed army without a port.

British commander Appleyard led the Allied expeditionary force to Bakalava to secure a port from which to deliver the supplies on which the invasion depended. The city fell on July 26, but then the Russians had received reinforcements from Galicia with whom they had begun to attack the expeditionary force to drive it back into the sea, but the English and Italians resisted tenaciously, managing to besiege Sevastopol. At the beginning of September there were about 50,000 Italians and 40,000 British in the Crimea who managed to distract 150,000 Russians by opening a new front in a strategic area. The flow of Russian divisions in the Crimea eased the pressure on the Balkan front where Vannovsky had to stop the offensive in Central Serbia, but managed to rejoin the Serbian army coming from the north.

With the arrival of winter, both sides reduced their military operations, limiting themselves to skirmishes along the border. The Russians had been contained to the north of the Balkan mountains but had reached the Serbs and extended the front line to the east, super-extending the already small Ottoman manpower that had to leave large sections of the Bulgarian front to the now 120,000 British from all over the empire that were taking on more and more of the war effort. The Italians were holding Sevastopol under siege, forcing the Russians to diverge more and more men on the peninsula. Great Russia had no manpower problems, but after three years of fighting it was losing many veterans and rapidly consuming previously accumulated reserves of war material. Russia's bad logistical situation had only recently begun to improve but not fast enough to ensure a continuous flow of supplies to the million men in the field, forcing commanders to conserve resources. The Russian high command told the Tsar that supplies for next year were not enough for a major offensive but that they would have to stay on the defensive until they resolved the situation or found an opening. The initiative thus passed into the hands of the allies.

The Balkans in late 1873

Last edited by a moderator:

Share: